Recovery of Indium Tin Oxide Metals from Mobile Phone Screens Using Acidithiobacillus spp. Bacterial Culture †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

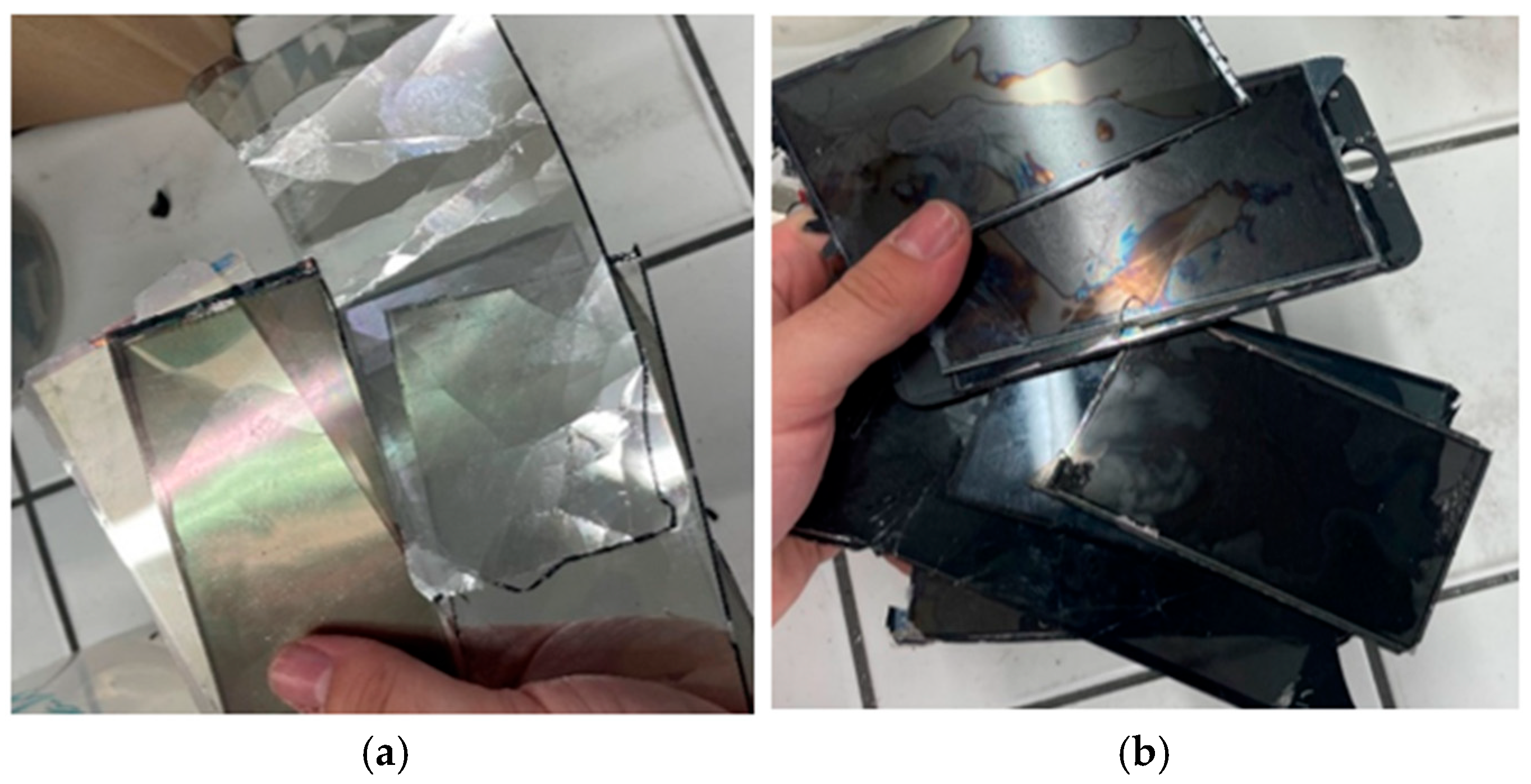

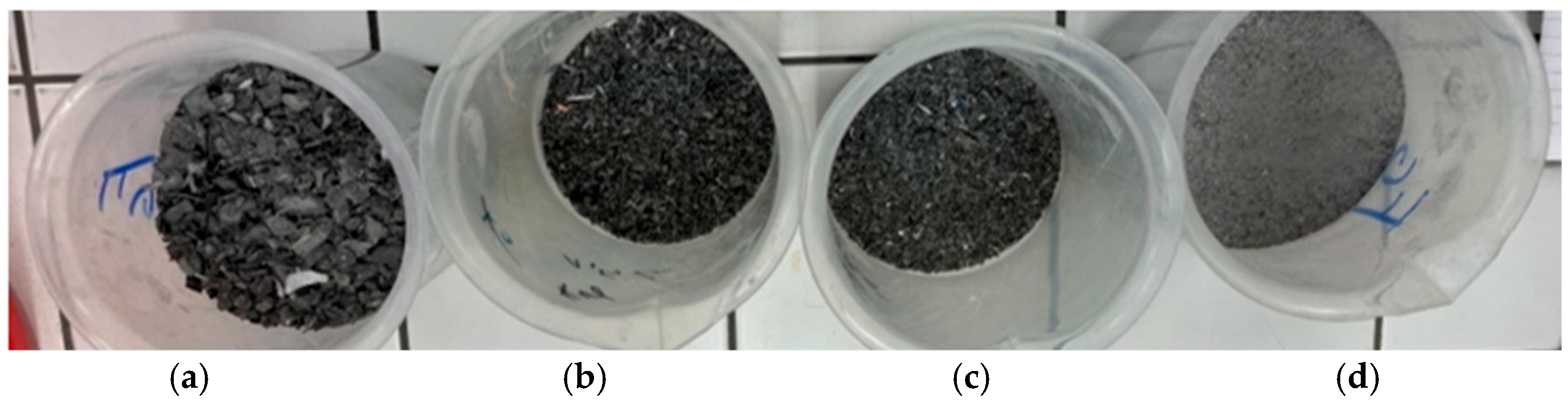

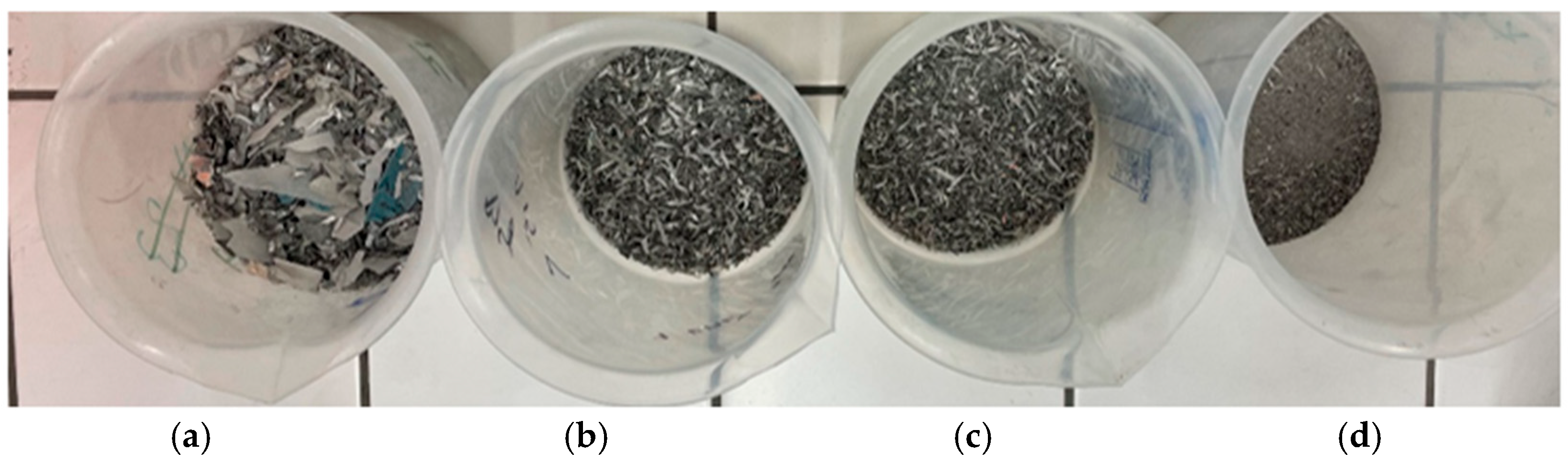

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Bioleaching

2.3. Elemental Analysis

2.3.1. XRF Analysis

2.3.2. ICP-OES Analysis of Solutions During and After Leaching

3. Results and Discussion

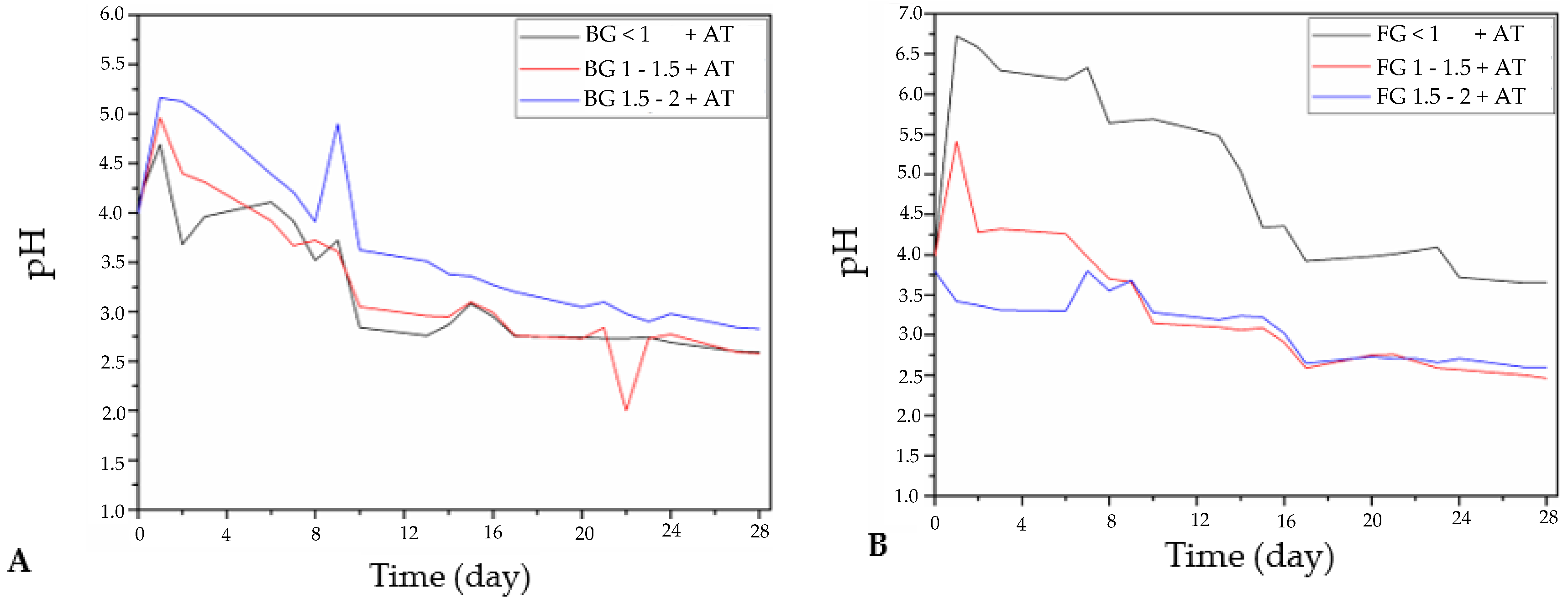

3.1. Leaching with Acidithiobacillus Thiooxidans

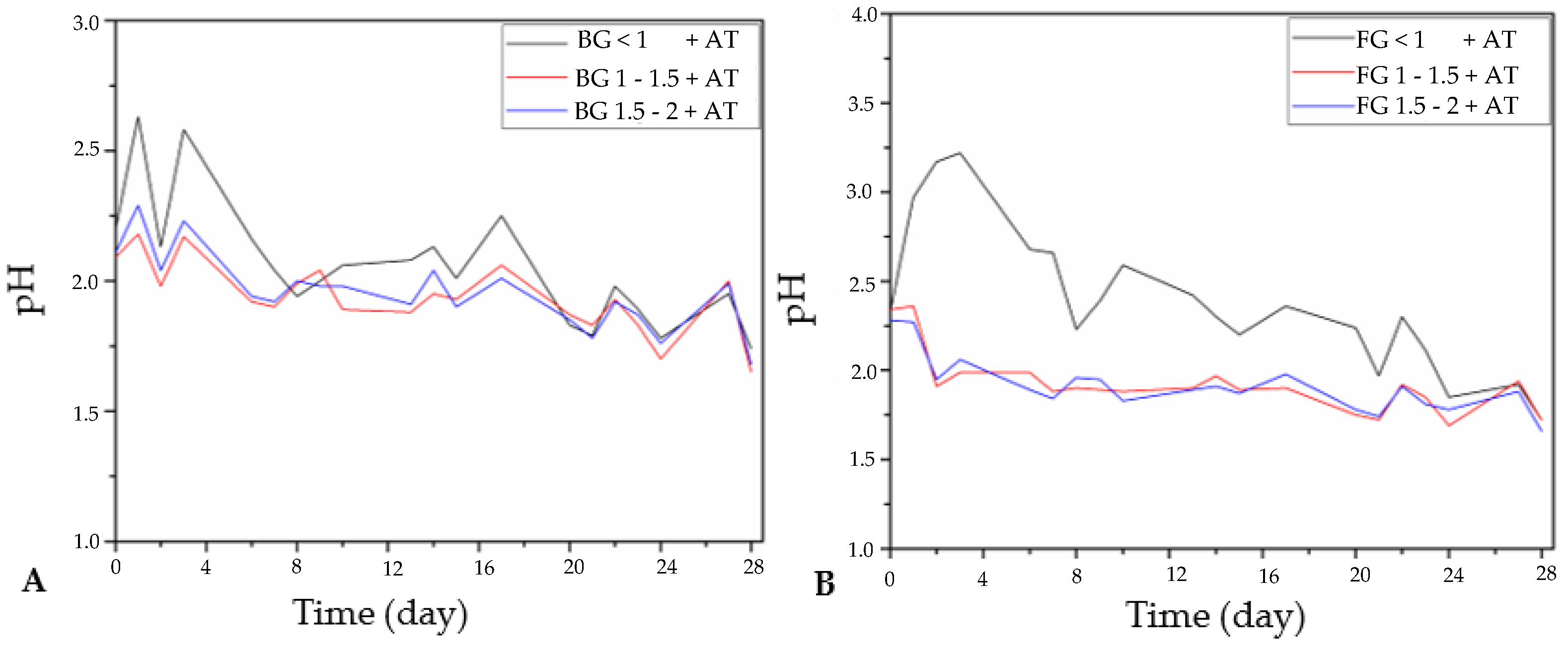

3.1.1. Changes in pH

3.1.2. Indium Detected by XRF Analysis

3.1.3. Indium Detected by ICP-OES Analysis

3.2. Leaching with Acidithiobacillus Ferrooxidans

3.2.1. Changes in pH

3.2.2. Indium Detected by XRF Analysis

3.2.3. Indium Detected by ICP-OES Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Electrical Equipment. Available online: https://www.mzp.cz/cz/elektrozarizeni (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Indium, In, Atomic Number 49. Available online: https://cs.institut-seltene-erden.de/indium-in-ordnungszahl-49/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Indium. Available online: http://www.prvky.com/49.html (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Indium–Tin Oxide. Available online: https://cz.sscmaterials.com/non-ferrous-metals/indium/indium-tin-oxide.html (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- European Commission. Report on Critical Raw Materials for the EU. Available online: https://rmis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/uploads/crm-report-on-critical-raw-materials_en.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- USGS Minerals Yearbook. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/indium-statistics-and-information (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Nakane, Y.; Masuta, H.; Honda, Y.; Fujimoto, F.; Miyazaki, T. Formation of indium–tin oxide (ITO) films by the dynamic mixing method. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2002, 59, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrometallurgy. Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/University_of_Missouri/MU%3A__1330H_%28Keller%29/23%3A_Metals_and_Metallurgy/23.3%3A_Hydrometallurgy (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Rocky, M.M.H.; Rahman, I.M.M.; Endo, M.; Hasegawa, H. Comprehensive insights into aqua regia-based hybrid methods for efficient recovery of precious metals from secondary raw materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Fu, B.; Dodbiba, G.; Fujita, T.; Fang, B. A sustainable approach to separate and recover indium and tin from spent indium–tin oxide targets. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 52017–52023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T. Efficient extraction and separation of indium from waste indium–tin oxide (ITO) targets by enhanced ammonium bisulfate leaching. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 269, 118766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Y. Differential leaching mechanisms and ecological impact of organic acids on ion-adsorption type rare earth ores. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojtová, T. Useful bacteria from waste help recover valuable metals. Universitas. Available online: https://www.universitas.cz/aktuality/6874-uzitecne-bakterie-z-odpadu-pomohou-ziskat-zpet-dulezite-kovy (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Jaiswal, M.; Srivastava, S. A review on sustainable approach of bioleaching of precious metals from electronic wastes. J. Hazard. Adv. 2024, 14, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, M.J.; Bahaloo-Horeh, N.; Mousavi, S.M.; Pourhossein, F.P. Bioleaching of indium from discarded liquid crystal displays. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, J.; Fornalczyk, A.F.; Saternus, M.S.; Gajda, B.G. Bioleaching of indium and tin from used LCD panels. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2018, 54, 639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Willner, J.; Fornalczyk, A.; Saternus, M.; Sedlakova-Kadukova, J.; Gajda, B. LCD panels bioleaching with pure and mixed culture of Acidithiobacillus. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2022, 58, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, A.; Pourhossein, F.; Ray, D.; Farnaud, S. Investigating the acidophilic microbial community’s adaptation for enhancement indium bioleaching from high pulp density shredded discarded LCD panels. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Zhu, N.; Mao, F.; Wu, P.; Dang, Z. Bioleaching of indium from waste LCD panels by Aspergillus niger: Method optimization and mechanism analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinharoy, A.; Lens, P.N.L. Indium removal by Aspergillus niger fungal pellets in the presence of selenite and tellurite. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 51, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITO Glass Used in LCD Modules. Available online: https://focuslcds.com/journals/ito-glass-used-in-lcd-modules/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Resistive vs. Capacitive Touchscreen Monitor. Available online: https://www.codeware.cz/blog/rezistivni-vs-kapacitni-dotykovy-monitor (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Janáková, I. Mineral Biotechnology I. University Textbook, VSB–Technical University of Ostrava, Ostrava, 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10084/152647 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Kovalčíková, M.; Luptakova, A.; Estokova, A. Application of granulated blast furnace slag in cement composites exposed to biogenic acid attack. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 96, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. What is XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence) and How Does It Work? Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/blog/ask-a-scientist/what-is-xrf-x-ray-fluorescence-and-how-does-it-work/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- UniversalLab Blog. Available online: https://universallab.org/blog/blog/ICP-OES-principle-and-pre-treatment-technique/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

| Samples for Leaching with A. thiooxidans | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Fractions FG a BG Layers | Weight of Fraction (g) | Amount of Media Waksmann and Joffe (mL) |

| 1 | BG < 1 | 10 | 100 |

| 2 | BG 1–1.5 | 10 | 100 |

| 3 | BG 1.5–2 | 10 | 100 |

| 4 | FG < 1 | 10 | 100 |

| 5 | FG 1–1.5 | 2 | 100 |

| 6 | FG 1.5–2 | 2 | 100 |

| Samples for Leaching with A. ferrooxidans | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Fractions BG a FG Layers | Weight of Fraction (g) | Amount of Media 9K (mL) |

| 7 | BG < 1 | 50 | 150 |

| 8 | BG 1–1.5 | 20 | 150 |

| 9 | BG 1.5–2 | 20 | 150 |

| 10 | FG < 1 | 50 | 150 |

| 11 | FG 1–1.5 | 10 | 150 |

| 12 | FG 1.5–2 | 10 | 150 |

| Fraction FG In content | |||

| Element (mg/kg) | <1 | 1–1.5 | 1.5–2 |

| In before leaching | 404 ± 11 | 279 ± 11 | 207 ± 10 |

| In after leaching with A. thiooxidans | 283 ± 11 | 242 ± 11 | 188 ± 10 |

| Fraction BG In content | |||

| Element (mg/kg) | <1 | 1–1.5 | 1.5–2 |

| In before leaching | 24 ± 3 | 14 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 |

| In after leaching with A. thiooxidans | 19 ± 3 | 7 ± 4 | 18 ± 4 |

| A Fraction BG indium (In) content | |||

| Element (mg/kg) | <1 | 1–1.5 | 1.5–2 |

| In before leaching | 24 ± 3 | 14 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 |

| In after leaching with A. ferrooxidans | 8 ± 3 | not detected | not detected |

| B Fraction FG indium (In) content | |||

| Element (mg/kg) | <1 | 1–1.5 | 1.5–2 |

| In before leaching | 404 ± 11 | 279 ± 11 | 207 ± 10 |

| In after leaching with A. ferrooxidans | 253 ± 8 | 53 ± 5 | 53 ± 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hrečin, D.; Janáková, I. Recovery of Indium Tin Oxide Metals from Mobile Phone Screens Using Acidithiobacillus spp. Bacterial Culture. Eng. Proc. 2025, 116, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116021

Hrečin D, Janáková I. Recovery of Indium Tin Oxide Metals from Mobile Phone Screens Using Acidithiobacillus spp. Bacterial Culture. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 116(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116021

Chicago/Turabian StyleHrečin, David, and Iva Janáková. 2025. "Recovery of Indium Tin Oxide Metals from Mobile Phone Screens Using Acidithiobacillus spp. Bacterial Culture" Engineering Proceedings 116, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116021

APA StyleHrečin, D., & Janáková, I. (2025). Recovery of Indium Tin Oxide Metals from Mobile Phone Screens Using Acidithiobacillus spp. Bacterial Culture. Engineering Proceedings, 116(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116021