Effectiveness of Filtrasorb Activated Carbon in Removing Selected Pharmaceuticals from Water †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

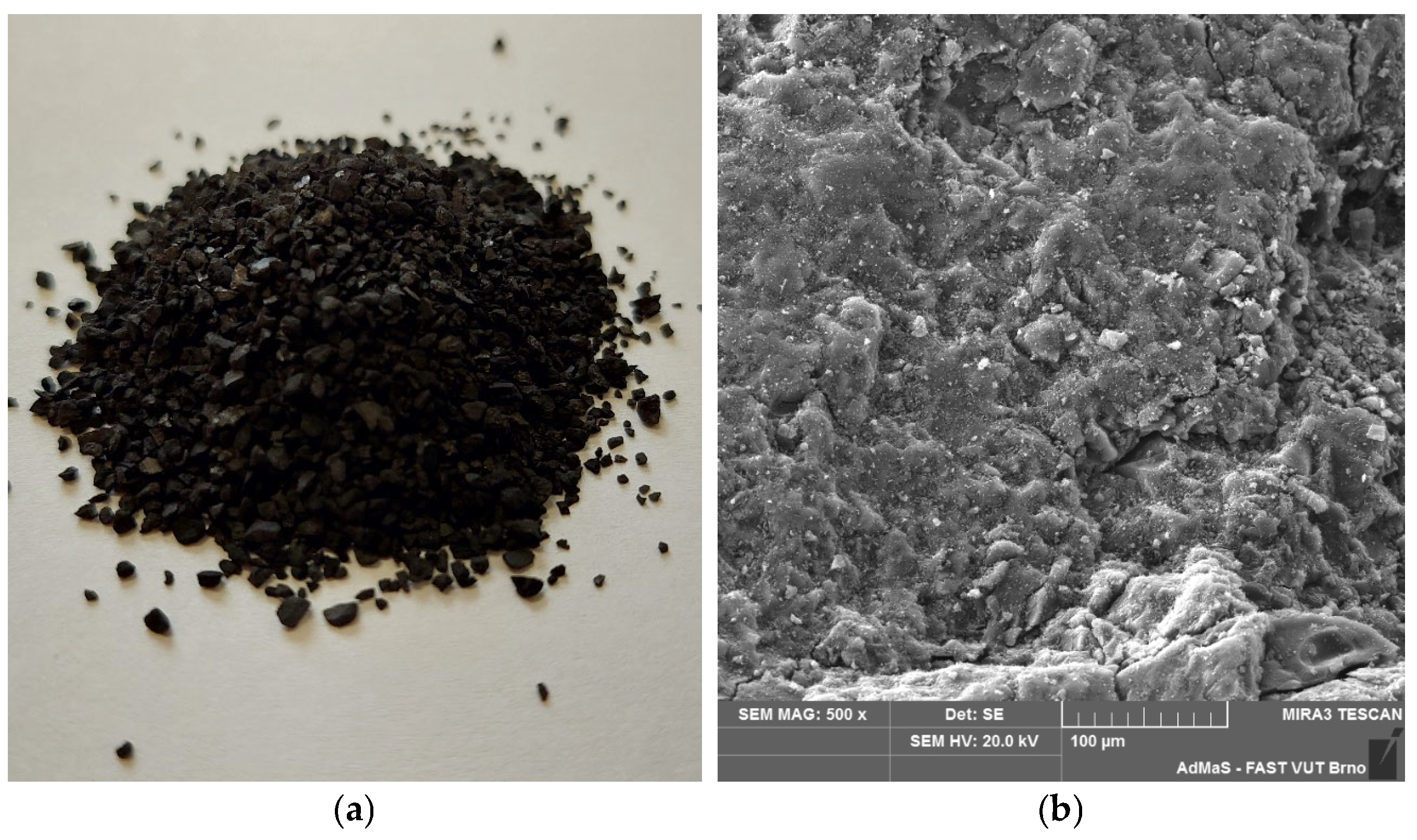

2.1. Characteristics of Selected Activated Carbons

2.2. Characteristics of Selected Pharmaceuticals

2.3. Laboratory Experiment

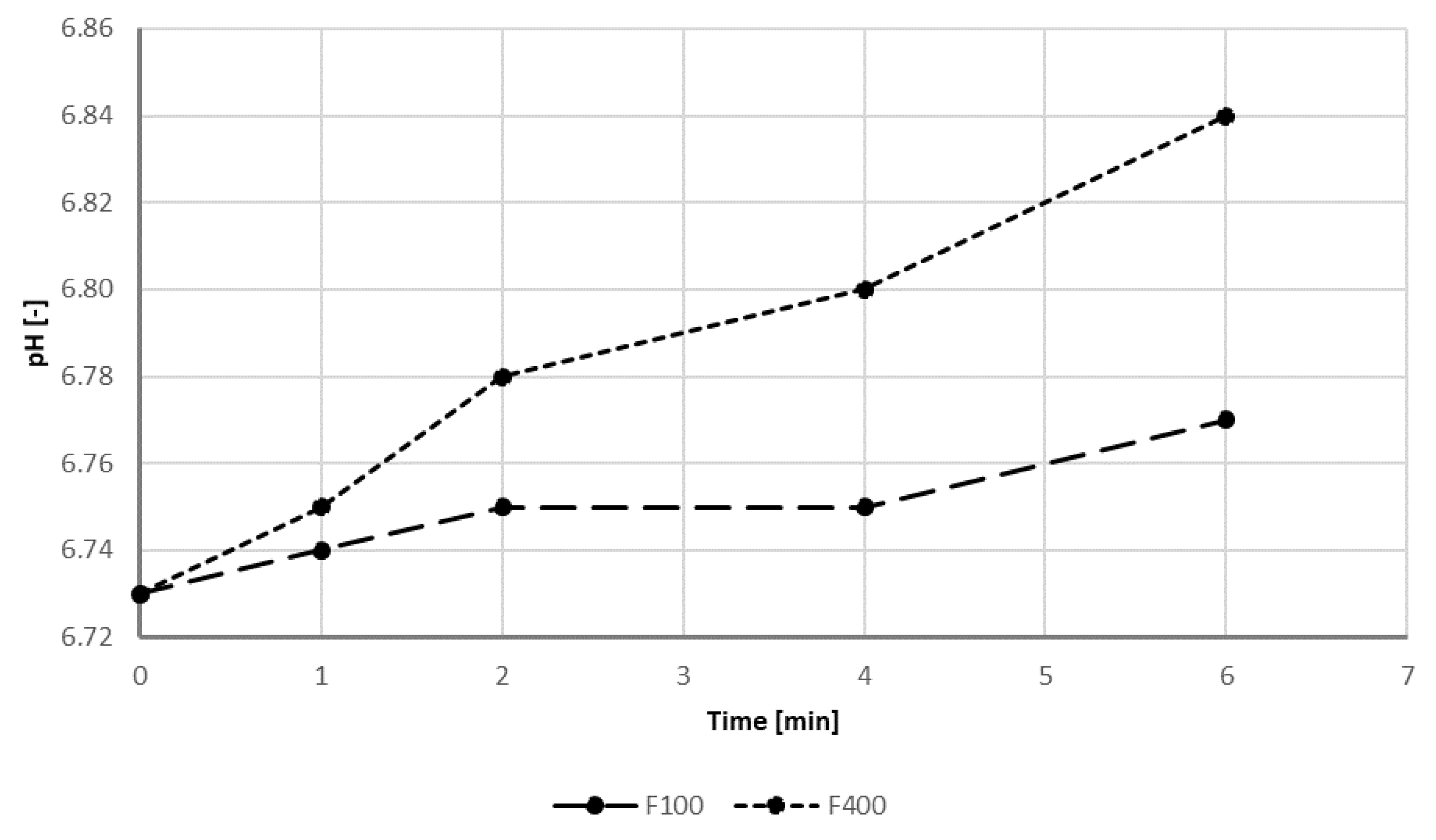

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPCPs | Personal care products |

| GAC | Granulated activated carbon |

| OTC | Over the counter |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| FNU | Formazin nephelometric unit |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| EBCT | Empty bed contact time |

References

- Teodosiu, C.; Gilca, A.F.; Barjoveanu, G.; Fiore, S. Emerging pollutants removal through advanced drinking water treatment: A review on processes and environmental performances assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1210–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ok, Y.S.; Kum, K.; Kwon, E.E.; Tsang, Y.F. Occurrences and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in drinking water and water/sewage treatment plants: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 596–597, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šíblová, D. Micropollutants in Water Resources and Ways of Their Elimination. Diploma Thesis, Brno University of Technology, Brno, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.; Costa, F.; Neves, I.C.; Tavares, T. Psychiatric Pharmaceuticals as Emerging Contaminants in Wastewater, 1st ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ranade, V.V.; Bhandari, V.M. Industrial Wastewater Treatment, Recycling and Reuse, 1st ed.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lukášová, D.; Biela, R.; Moravčíková, S. Adsorption capacity assessment for selected adsorbents in the removal of over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics from water. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 274, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filtrasorb F100. Available online: https://www.calgoncarbon.com/app/uploads/DS-FILTRA10019-EIN-E1.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Filtrasorb F400. Available online: https://www.calgoncarbon.com/app/uploads/DS_FILTRASORB_400_FINAL_02212025.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Niedermayerová, I. Over-the-counter headache preparations—Correct selection and possible risks. Praktické lékárenství 2015, 11, 141–143. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Mann, J. Poisons, Drugs, Medicines, 1st ed.; Academia: Prague, Czech Republic, 1996; pp. 55–96. [Google Scholar]

- Vávrová, M.; Landová, P.; Švestková, T.; Burešová, J. Determination of ibuprofen and diclofenac in surface waters by LC-MS-MS. Chem. Listy 2018, 112, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, T.J. Diclofenac: An update on its mechanism of action and safety profile. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010, 26, 1715–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brogden, R.N.; Pinder, R.M.; Sawyer, P.R. Naproxen: A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy and use. Drugs 1975, 9, 326–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belay, E.D.; Bresee, J.S.; Holman, R.C.; Khan, A.S.; Shahriari, A.; Schonberger, L.B. Reye’s syndrome in the United States from 1981 through 1997. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, G.G.; Davies, M.J.; Day, R.O.; Mohamudally, A.; Scott, K.F. The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: Therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings. Inflammopharmacology 2013, 21, 201–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degree No. 252/2004 Coll, Laying Down Hygienic Requirements for Drinking and Hot Water and Frequency and Scope of Drinking Water Control, as Amended. Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic. Available online: https://www.zakonyprolidi.cz/cs/2004-252 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- KNAPPE (Knowledge and Need Assessment on Pharmaceutical Products in Environmental Waters). Specific Support Action Project. Available online: https://global.noharm.org/media/4069/download?inline=1 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Biela, R.; Šíblová, D.; Kabelíková, E.; Švestková, T. Laboratory elimination of ibuprofen from water by selected adsorbents. Desalination Water Treat. 2020, 193, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biela, R.; Šopíková, L. Efficiency of sorption materials on the removal of lead from water. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2017, 15, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitter, P. Hydrochemistry, 4th ed.; University of Chemical Technology: Prague, Czech Republic, 2009; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Horáková, M.; Lischke, P.; Grünwald, A. Chemical and Physical Methods of Water Analysis, 1st ed.; State Publishing House of Technical Literature: Prague, Czech Republic, 1986; pp. 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tuhovčák, L.; Adler, P.; Kučera, T.; Raclavský, J. Water Industry, 1st ed.; Brno University of Technology: Brno, Czech Republic, 2006; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Delpasand, M.; Loaiciga, H. Water quality, hygiene, and health. In Economical, Political, and Social Issues in Water Resources, 1st ed.; Bozorg-Haddad, O., Ed.; Elsevier: New Delhi, India, 2021; pp. 217–257. [Google Scholar]

- Worch, E. Adsorption Technology in Water Treatment: Fundamentals, Processes and Modeling, 1st ed.; De Gruyter: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kowa Limited Liability Company. Filter Materials and Chemicals for Water Treatment. Available online: https://www.kowa.cz/komponenty-pro-upravu-vody/filtracni-hmoty-a-chemikalie/aktivni-uhli (accessed on 24 June 2025).

| Parameter | Unit | F100 | F400 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific adsorption surface | m2/g | 850 | 1050 |

| Methylene blue | mg/g | 230 | 300 |

| Atrazine 1 µg/L | mg/g | 40 | 40 |

| Trichloroethylene 50 µg/L | mg/g | 25 | 20 |

| Effective size | mm | 0.8–1.0 | 0.55–0.75 |

| Bulk mass | kg/m3 | 500 | 450 |

| Iodine number | mg/g | 850 | 1000 |

| Parameter | Unit | Value | Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | mg Pt/L | 4 | 20 |

| Turbidity | FNU | 0.6 | 5 |

| Iron | mg/L | 0.03 | 0.2 |

| pH | - | 7.39 | 6.5–9.5 |

| Total hardness | mmol/L | 2.66 | 2–3.5 |

| Ammonium ions | mg/L | <0.03 | 0.5 |

| Nitrates | mg/L | 31.6 | 50 |

| Nitrites | mg/L | <0.005 | 0.5 |

| Chlorides | mg/L | 20.4 | 100 |

| Coliform bacteria | CFU/100 mL | 0 | 0 |

| Escherichia coli | CFU/100 mL | 0 | 0 |

| Time [min] | Ibuprofen [µ/L] | Diclofenac [µ/L] | Naproxen [µ/L] | Paracetamol [µ/L] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.391 | 0.346 | 0.526 | 0.465 |

| 1 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| 2 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| 4 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| 6 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Time [min] | Ibuprofen [%] | Diclofenac [%] | Naproxen [%] | Paracetamol [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | >87.2 | >85.5 | >81.0 | >78.5 |

| 2 | >87.2 | >85.5 | >81.0 | >78.5 |

| 4 | >87.2 | >85.5 | >81.0 | >78.5 |

| 6 | >87.2 | >85.5 | >81.0 | >78.5 |

| Parameter | Unit | F100 | F400 |

|---|---|---|---|

| h | m | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Qt | m3/h | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| AR | m2 | 0.00152 | 0.00152 |

| EBCT | min | 2.43 | 2.74 |

| VR | m3 | 0.0012 | 0.0014 |

| vf | m/hr | 19.73 | 19.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biela, R.; Lukášová, D. Effectiveness of Filtrasorb Activated Carbon in Removing Selected Pharmaceuticals from Water. Eng. Proc. 2025, 116, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116013

Biela R, Lukášová D. Effectiveness of Filtrasorb Activated Carbon in Removing Selected Pharmaceuticals from Water. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 116(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116013

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiela, Renata, and Daniela Lukášová. 2025. "Effectiveness of Filtrasorb Activated Carbon in Removing Selected Pharmaceuticals from Water" Engineering Proceedings 116, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116013

APA StyleBiela, R., & Lukášová, D. (2025). Effectiveness of Filtrasorb Activated Carbon in Removing Selected Pharmaceuticals from Water. Engineering Proceedings, 116(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025116013