1. Introduction

The real-time recognition of printed music notation using computer vision and deep learning generally addresses two core aspects: optical music recognition and real-time symbol detection. In Ref. [

1], the authors present an end-to-end deep convolutional neural network model based on the Darknet-53 backbone (from YOLO [

2]) for music symbol detection. The use of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for sequential music score reading and contextual retention is discussed in Ref. [

3]. Similarly, Ref. [

4] introduces a Connectionist Temporal Classification loss function to improve the system’s ability to generalize across various types of monophonic sheet music. Since RNNs compute the loss function in a serial manner, often resulting in low training efficiency and convergence difficulties, Ref. [

5] proposes a sequence-to-sequence framework based on a transformer architecture with a masked language model, which yields improved accuracy.

The computation of optimal finger positions and movements has become an increasingly prominent topic in robotics. For instance, the robotic marimba player “Shimon” employs Brushless Direct Current (BLDC) motors to enhance both speed and dynamic range. This system achieves a performance level comparable to that of human musicians and surpasses solenoid-based systems in striking speed, thereby enabling more expressive robotic musical performances [

6]. In Ref. [

7], the authors introduce a real-time motion planning approach for multi-fingered robotic hands operating in constrained environments. Their method uses neural networks to model collision-free spaces, facilitating dynamic obstacle avoidance and improving dexterity in in-hand manipulation tasks. A comprehensive review of motion planning algorithms is provided in Refs. [

8,

9], offering insights into the performance, strengths, and limitations of various planners, along with guidance for selecting appropriate algorithms based on specific application requirements.

Controller-driven robotic actuators have advanced the field of robotic musical performance by addressing the challenges of precise actuation and expressive control. For example, Ghost Play [

10] is designed to emulate human violin performances using seven electromagnetic linear actuators: three for bowing and four for fingering. Another implementation of Shimon, which also utilizes BLDC motors for enhanced speed, is described in Ref. [

6]. The development of anthropomorphic robots capable of playing the flute and saxophone, which mimic human physiology and control mechanisms, is discussed in Ref. [

11].

Microcontroller-based implementations for piano-playing robots, which focus on driving actuators for precise key presses and dynamic articulation, are introduced in Refs. [

12,

13,

14]. A more advanced platform is described in Ref. [

15], where an Arduino Mega board is employed. These projects collectively demonstrate the versatility of microcontrollers such as Arduino in automating piano performances.

Recent OMR frameworks such as Audiveris, OpenOMR, and Refs. [

16,

17,

18] offer robust pipelines for symbol recognition and semantic reconstruction. In the context of robotic music performance, advanced systems like the two-hand robot [

19] represent the frontier of human-like articulation. Moreover, the broader field of Music Information Retrieval (MIR) [

20] explores expressive performance modeling, audio-to-score alignment, and emotion-aware playbacks—areas that align closely with the goals of our robotic system.

This work contributes to the field of intelligent robotic performance by proposing a fully integrated end-to-end system that combines computer vision, AI-driven music interpretation, motion planning, and mechanical actuation. Unlike previous systems that addressed individual components (e.g., OMR or actuation), our pipeline translates visual sheet music into executable trajectories with temporal synchronization and mechanical accuracy. The novelty lies in the real-time heuristic motion planner that dynamically groups notes and optimally assigns fingers using a cost-based formulation. Additionally, we present a modular 32-DoF robotic hand design capable of three-dimensional motion with formal latency and precision validation.

2. Materials and Methods

Robotic systems that integrate computer vision and machine learning techniques have demonstrated significant potential across a wide range of applications, from autonomous navigation to human–computer interaction. In this study, we propose a novel approach to musical performance automation using a robotic platform capable of interpreting and executing musical scores using image-based analysis and precise actuation.

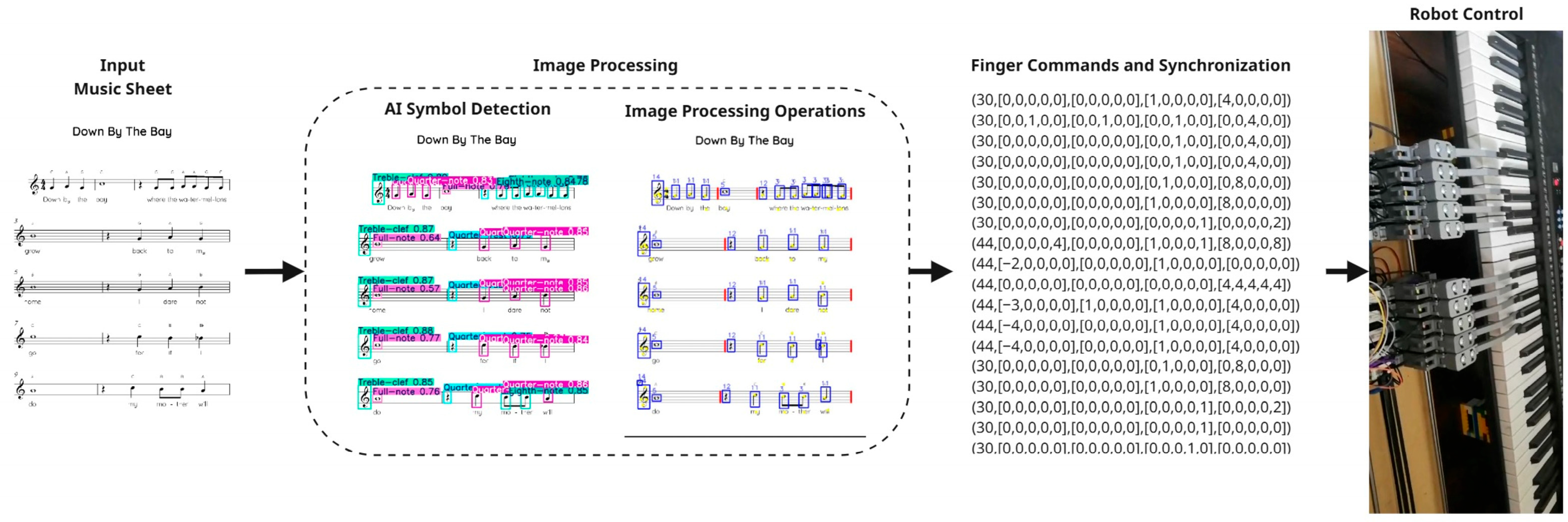

The developed robotic system integrates advanced computer vision techniques, artificial intelligence-driven algorithms, and precise robotic actuation into a structured workflow, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The workflow is divided into distinct processing modules. Initially, the system performs image acquisition by capturing a high-resolution image of the musical sheet. This captured image serves as the input for subsequent modules.

Following acquisition, the image-processing module employs a combination of sophisticated techniques. A YOLO-based neural network detects and classifies musical symbols such as notes, rests, clefs, and accidentals. In parallel, advanced image processing algorithms are utilized to remove staff lines and accurately identify the note positions on the processed sheet music.

Subsequently, a dedicated finger position control module calculates optimal finger placements and movement trajectories. This module employs heuristic algorithms to optimize both finger and hand motions while synchronizing the temporal sequence of the performance. The motion planning strategy incorporates dynamic positioning and collision avoidance to ensure both precision and efficiency.

Finally, the computed control commands from the finger position control module are transmitted to microcontroller that drives robotic actuators, enabling precise key presses and dynamic articulations, ultimately resulting in a coherent, expressive, and realistic musical performance.

2.1. The Image Processing Module

The accurate representation of musical notes requires the determination of two critical attributes: duration and pitch. To achieve this, the image processing module integrates advanced detection techniques, employing a YOLO-based neural network for symbol detection and image processing algorithms for pitch estimation [

15].

2.1.1. AI Symbol Detection

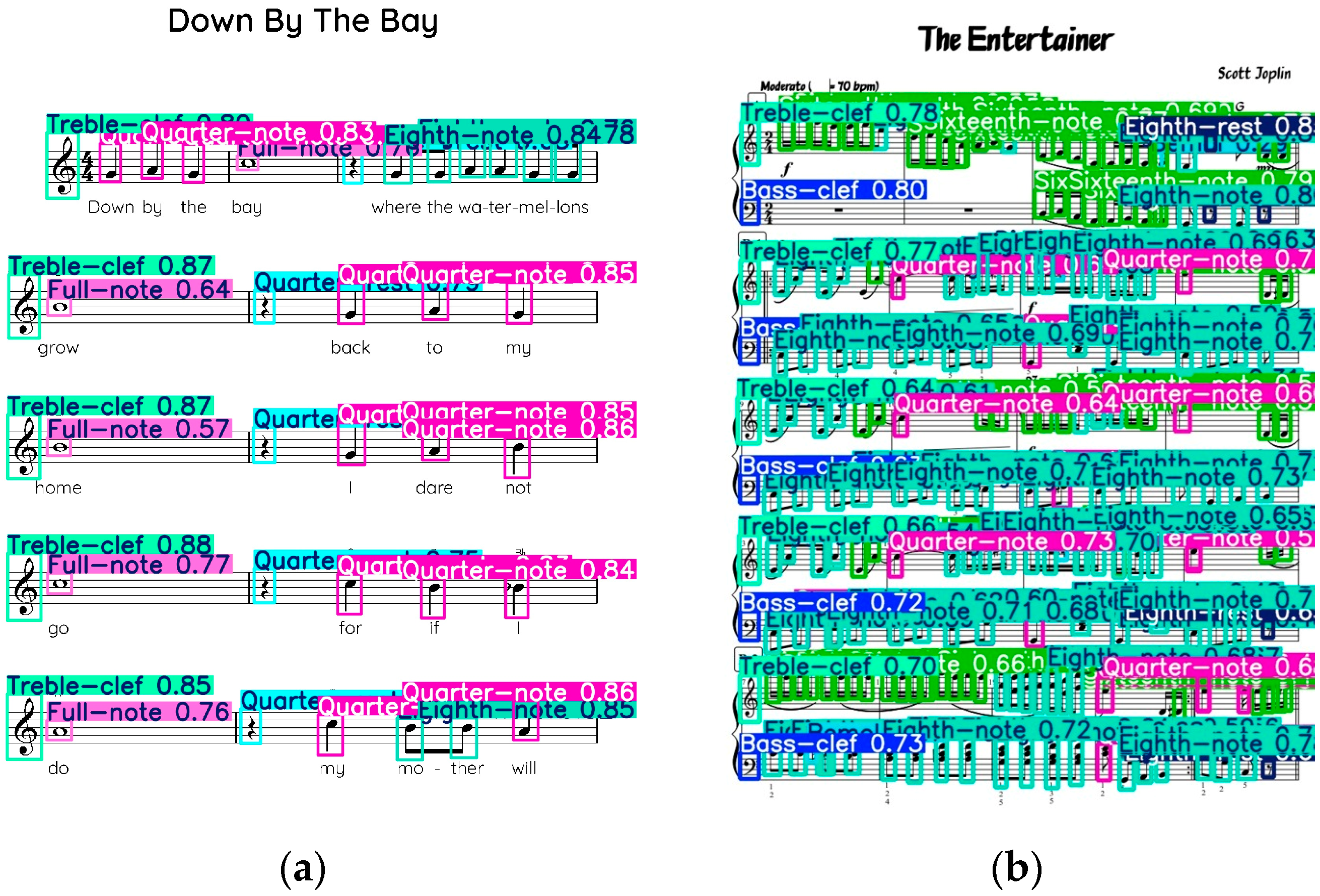

The YOLOv8 neural network model was utilized to detect musical symbols within the sheet music images. The model was trained on a comprehensive dataset obtained from publicly available sources, specifically selected to include relevant and frequently represented musical notation classes. The resulting model identifies 14 distinct classes, encompassing note durations, rests, clefs, and accidentals. The performance of the model was evaluated using the mean Average Precision (mAP), achieving an impressive accuracy of 96% at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 (mAP50) and 63% across multiple IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP50–95). Some results can be seen in

Figure 2.

2.1.2. Image Processing-Based Pitch Detection

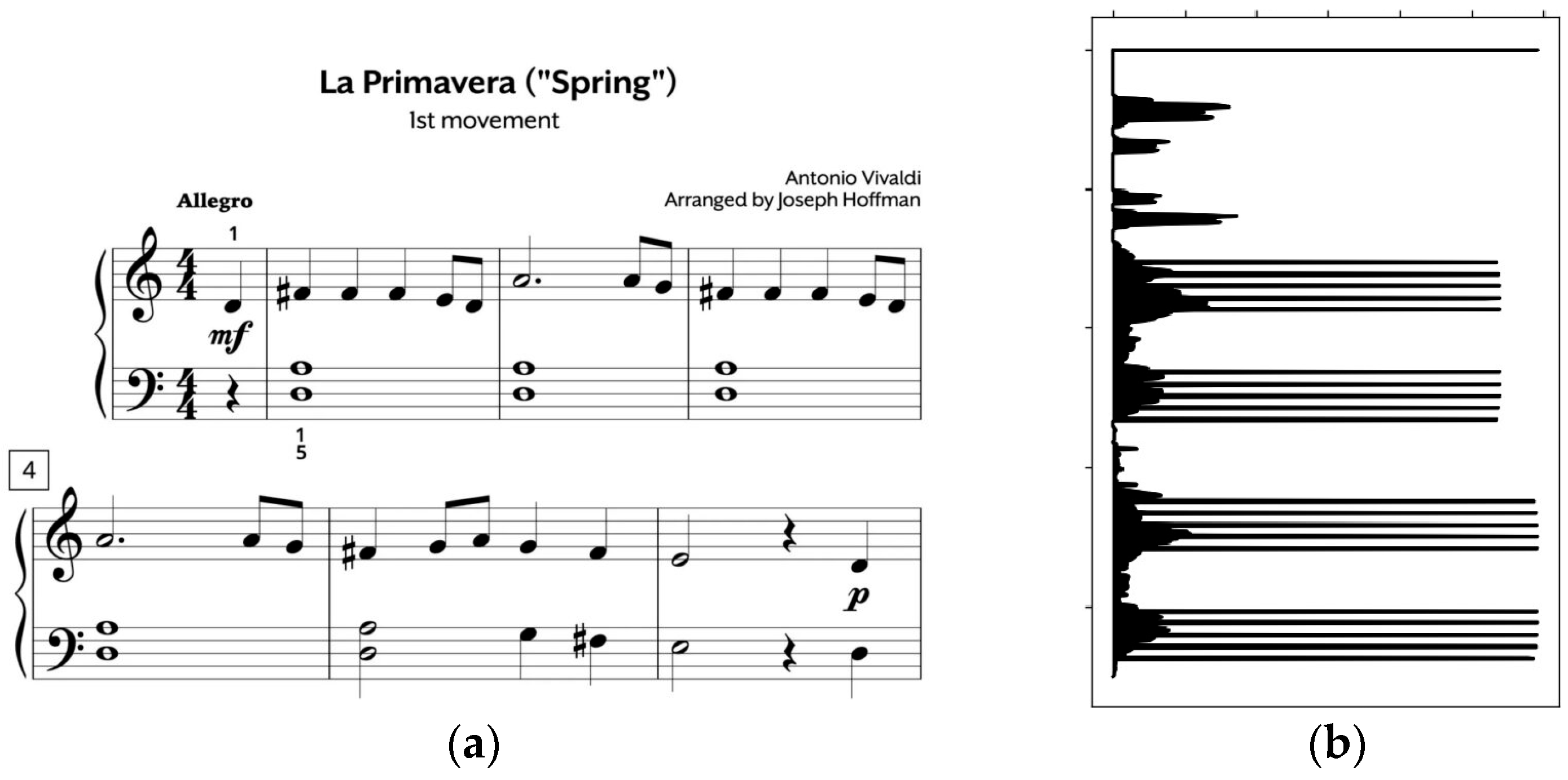

The pitch of a note is determined by the relative position of its notehead on the staff lines; therefore, accurately locating the center of the notehead is a critical step. However, for the improved detection of noteheads, it is necessary to first remove the staff lines. To achieve this, a row-wise histogram is computed by counting the number of black pixels in each row of the inverted binary image, in which black pixels are represented by a value of 1 and white pixels by 0. This ensures that the histogram reflects the density of black pixels per row. The histogram

is computed as follows:

where

denotes the histogram value at row

,

is the width of the image, and

represents the binary pixel intensity at coordinates

in the inverted image. The peaks in the histogram correspond to the positions of staff lines (see

Figure 3). Only groups of five closely spaced peaks are considered as valid staff candidates.

The vertical positions (y-coordinates) of the detected staff lines are retained for subsequent processing. Staff line removal is performed by detecting and eliminating short vertical runs of black pixels. Following the removal of staff lines, noteheads are detected using a structured image processing pipeline. A copy of the image is prepared to address potential fragmentation of noteheads caused during line removal. Morphological closing with an elliptical structuring element is applied to reconnect fragmented components, followed by horizontal filtering and hole filling to restore complete notehead shapes. Morphological opening is then used to enhance elliptical features.

From the resulting shapes, only those with a circularity above a certain threshold are retained. Circularity is computed according to the following equation:

Finally, contours corresponding to elliptical structures are extracted and merged, and their centroids are computed and sorted to precisely determine the notehead positions.

Bar lines are identified as vertical structures with consistent height and alignment using rectangular filters. Unlike note stems or flags, they maintain uniform vertical positioning. Bar lines are essential for segmenting music into measures, enabling accurate temporal synchronization, especially in multi-hand performances.

2.2. Finger Commands and Synchronization Module

The finger command and synchronization module are responsible for calculating the precise timing, finger movements, and synchronization required for musically accurate robotic performances. Utilizing the detected musical information (pitch and duration), heuristic algorithms first establish a coherent temporal sequence, defining exact timings for note initiation and duration.

A mathematical framework synchronizes each note’s execution timing, represented as

where

is the start time of the current note,

is the start time of the preceding note, and

is the duration of the preceding note.

Once the temporal sequence is established, the module calculates optimal finger positioning and hand placements. The algorithm is based on the central hypothesis that notes group together within the span of a single hand. As a result, the subsequent positions of the hand are calculated as

where

denotes the optimal position of the hand for the

k-th group of notes, calculated as the median of the note positions

within the group

. A new group is formed whenever a note exceeds the reach of the hand. The grouping process ensures that hand movements are optimized while avoiding collisions between hands.

For finger assignment, the task is posed as an optimization task, where the goal is to minimize the total cost of assigning fingers to notes based on reachability, distance, and collision constraints. This is solved using the Jonker–Volgenant algorithm, applied to a cost matrix

, where

represents the cost of assigning finger

i to note

j. The optimization objective is

where

is the number of available fingers,

is the number of notes in the current group, and

if finger

is assigned to note

and

otherwise.

The computed trajectories are converted into commands sent to the microcontroller, where a state machine manages transitions between phases such as pressing, holding, releasing, and repositioning. This structured control ensures coordinated and deterministic hand and finger movements, enabling accurate and expressive playback.

2.3. Robotic Hardware Design

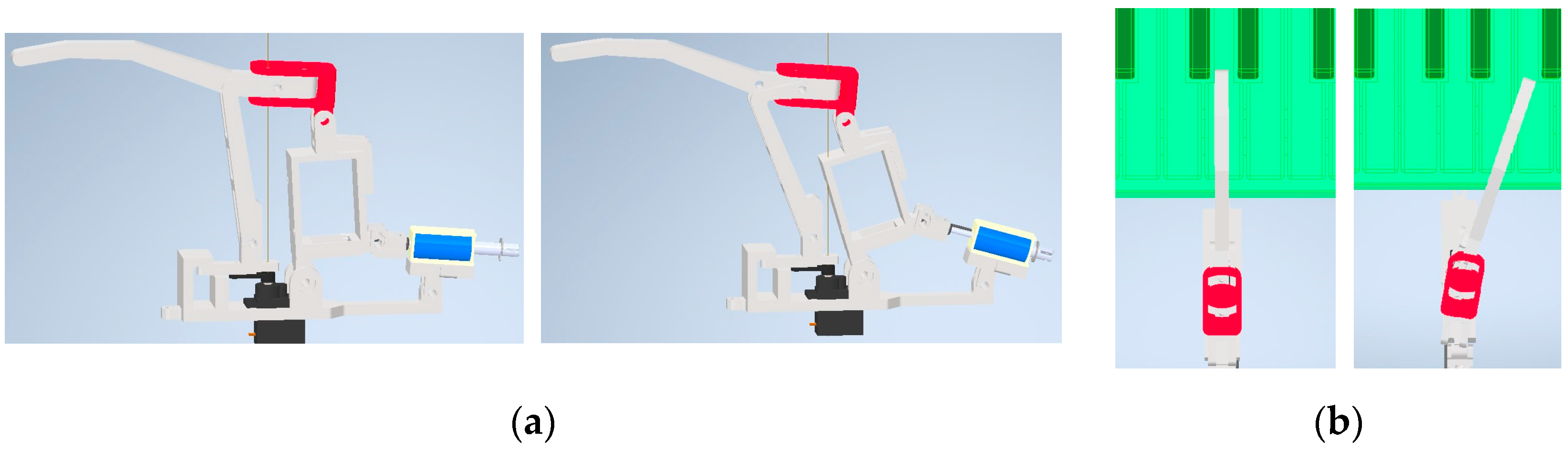

The robotic system comprises two anthropomorphic hands, each designed to replicate the human dexterity required for nuanced piano performance. Each hand consists of five fingers, with each finger providing three distinct degrees of freedom (DoFs). Mathematically, the system’s degrees of freedom can be expressed as

Each finger’s three degrees of freedom encompass vertical displacement for key pressing, horizontal extension to reach black keys (

Figure 4a), and lateral rotation for positioning on adjacent keys (

Figure 4b). Vertical and horizontal movements are actuated through high-precision solenoids operating at 24 V and drawing 0.75 A, ensuring robust and responsive actuation. Lateral rotational movements are controlled by servo motors, providing accurate angular positioning critical for precise key selection.

Each robotic hand is mounted on a belt-driven linear rail system, allowing for translational movement along the full range of the keyboard. This motion is facilitated by stepper motors, providing precise positioning of the hands across the piano range. All actuators, including solenoids, servos, and stepper motors are controlled using a microcontroller.

3. Results

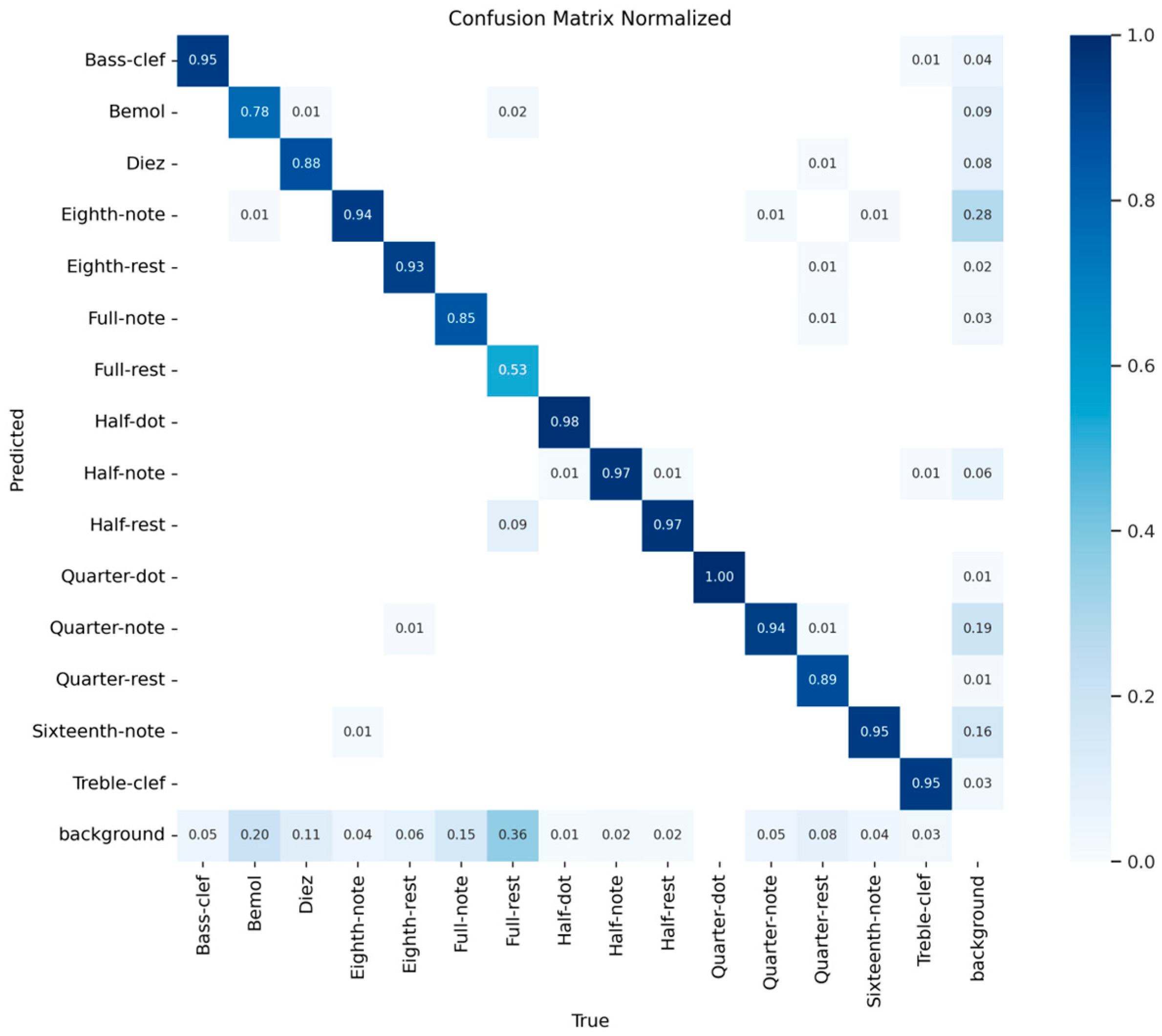

The robotic system was evaluated using digitally typeset Western music scores under controlled conditions to assess its performance across three primary dimensions: symbol recognition, motion planning, and mechanical execution. The image processing module, powered by a YOLOv8 neural network, demonstrated high accuracy in detecting musical symbols. The model achieved a mean Average Precision of 96% at an Intersection over Union threshold of 0.5 and 63% across a broader range of thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95. These results indicate strong performance in recognizing common musical elements such as note durations, rests, clefs, and accidentals. However, the model’s accuracy declined when encountering rare or complex symbols, a limitation attributed to the underrepresentation of such classes in the training dataset. The confusion matrix in

Figure 5 reveal that misclassifications were most frequent among visually similar note types, underscoring the need for more diverse training data.

The motion-planning module was verified using simulated playback of known musical pieces. The output timing sequences and finger-to-note assignments were compared against manually annotated ground truth data derived from MIDI files corresponding to the same score. Timing accuracy was evaluated by measuring deviations in note onset times, which consistently remained within a ±60 ms window, sufficient for perceptual musical coherence.

For the mechanical execution module, a structured test suite was designed to assess repeatability, positional accuracy, and response time. Key positions across the full keyboard range were targeted sequentially, and finger actuation latency was measured using a microcontroller-based timing mechanism. Specifically, external interrupts were used to capture the time interval between command issuance and key depression, as detected by contact sensors mounted beneath the keys. The measured average actuation delay was 85 ms, with a standard deviation of 12 ms. Mechanical repeatability tests showed less than 2 mm positional deviation over 20 trials per finger. These evaluations confirm the system’s ability to generate reliable and precise motions for real-time piano performances.

4. Discussion

The results of this study highlight the potential of integrating computer vision, artificial intelligence, and robotic actuation in the domain of autonomous musical performance. The system’s modular architecture allowed for the independent development and optimization of each subsystem, contributing to its overall robustness and adaptability. The high accuracy of the symbol detection module, particularly for standard notation, validates the use of YOLO-based neural networks in real-time music interpretation. The motion planning algorithms, while heuristic in nature, proved to be effective in generating synchronized and efficient finger trajectories, enabling the robot to perform musical passages with a degree of fluency and coordination.

While the hardware limits dynamic key force, it must also be noted that expressive performance elements—such as dynamics (e.g., forte/piano), articulation (e.g., staccato, legato), and tempo variation—are not yet extracted during the OMR phase. Therefore, the current pipeline performs a rhythmically accurate but expressively neutral playback. Future work will involve enhancing the symbol detection module to recognize expressive annotations and extending the motion planner to include dynamic key velocity and tempo control, thus improving musicality beyond structural accuracy.

While generally effective, the motion planning module does not guarantee globally optimal solutions. Rapid note sequences and chromatic runs sometimes led to suboptimal finger assignments and inefficient hand movements. Occasional desynchronization between hands, e.g., during horizontal translations, further underscores the need for more advanced algorithms that consider execution latency and anticipate future movements.

Future work should address the simplifying assumptions of the current system, such as reliance on digitally typeset scores, fixed clefs and tempo, and the omission of ornaments and extended techniques. While these constraints eased implementation, they limit real-world applicability. Enhancing the system to handle handwritten scores, dynamic tempo, and expressive articulations would greatly improve its versatility.

Several improvement opportunities were identified during development. Replacing solenoids with proportional actuators would enable dynamic key control for enhanced expressiveness. Expanding the training dataset would improve recognition accuracy, while incorporating predictive models or reinforcement learning could yield more adaptive and efficient motion planning, especially for fast or complex passages.

5. Conclusions

The developed 32-DoF robotic system successfully demonstrated its ability to autonomously interpret and perform piano music on selected pieces, based on quantitative and qualitative evaluations. The system achieved timing deviations within ±60 ms and classification accuracy above 96% for standard symbols.

The YOLOv8-based model showed high accuracy in recognizing standard notation, while the heuristic motion planner produced coherent, synchronized finger trajectories. Experimental validation confirmed its reliable timing and mechanical precision in executing complex passages. Despite some limitations in expressiveness and symbol generalization, the system effectively delivers structured and musically coherent performances.