Supporting Rule-Based Control with a Natural Language Model †

Abstract

1. Introduction

Related Work

2. Proposed Approach

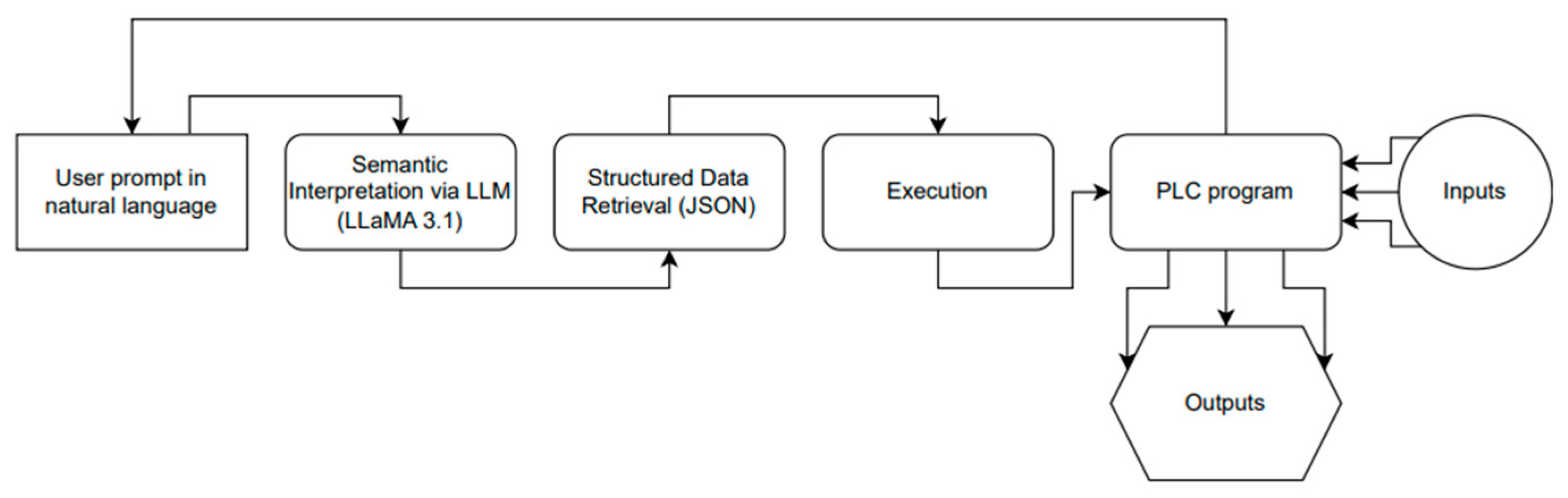

3. Model of Rule-Based Control with NLP

- A user provides a natural language prompt as the system’s input for the system.

- The prompt is processed by the LLaMA 3.1 large language model.

- The model interprets the user’s instruction.

- A predefined list of steps written in JSON format is loaded. Each entry in the file maps a natural language action to its corresponding register value and control logic.

- The model finds the appropriate predefined action for the user’s request.

- Based on the matched action, the system retrieves the associated numerical value required for execution.

- This value is written into a specific Modbus register that is monitored by the PLC.

- The PLC reads the value and performs the corresponding control operation.

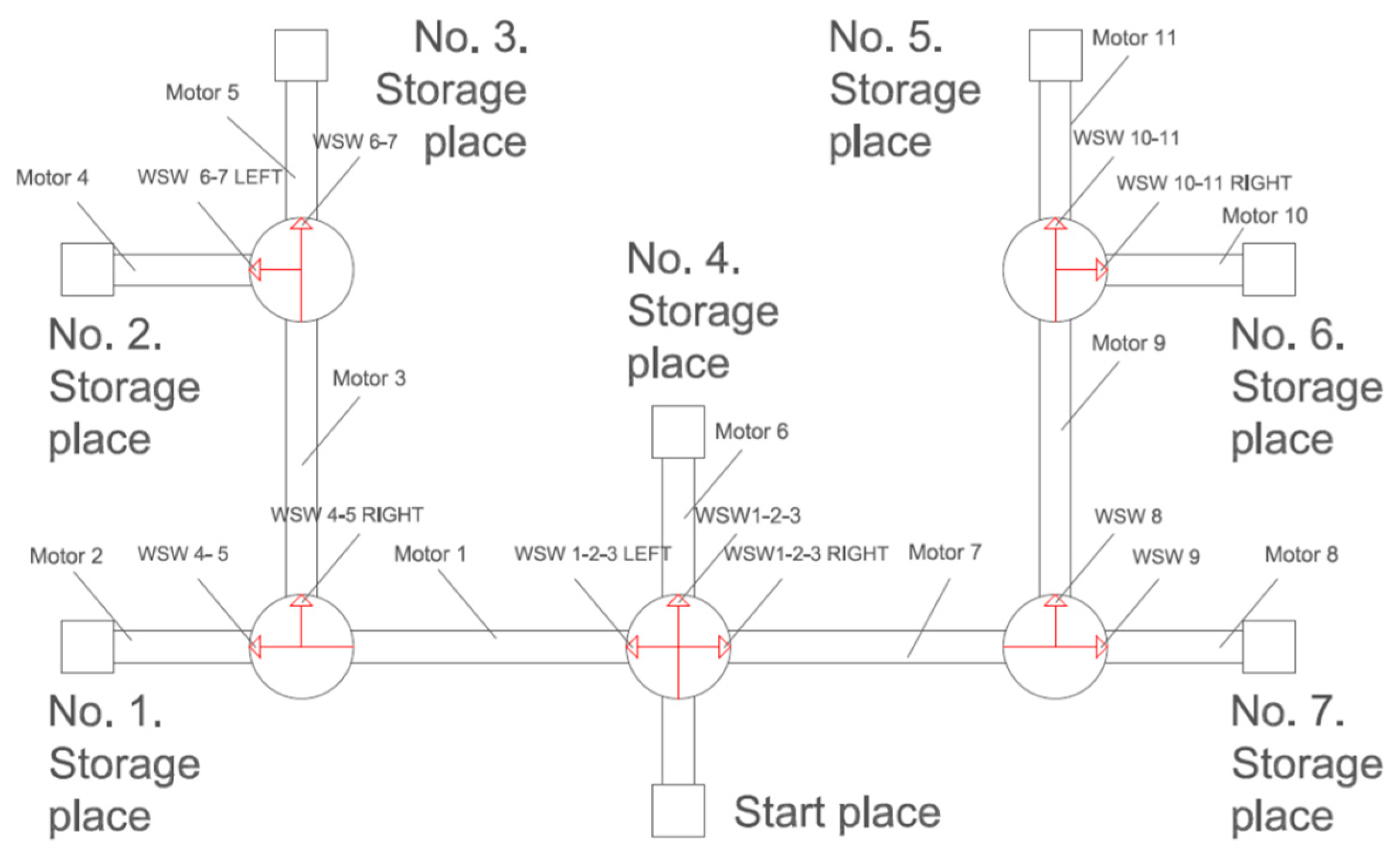

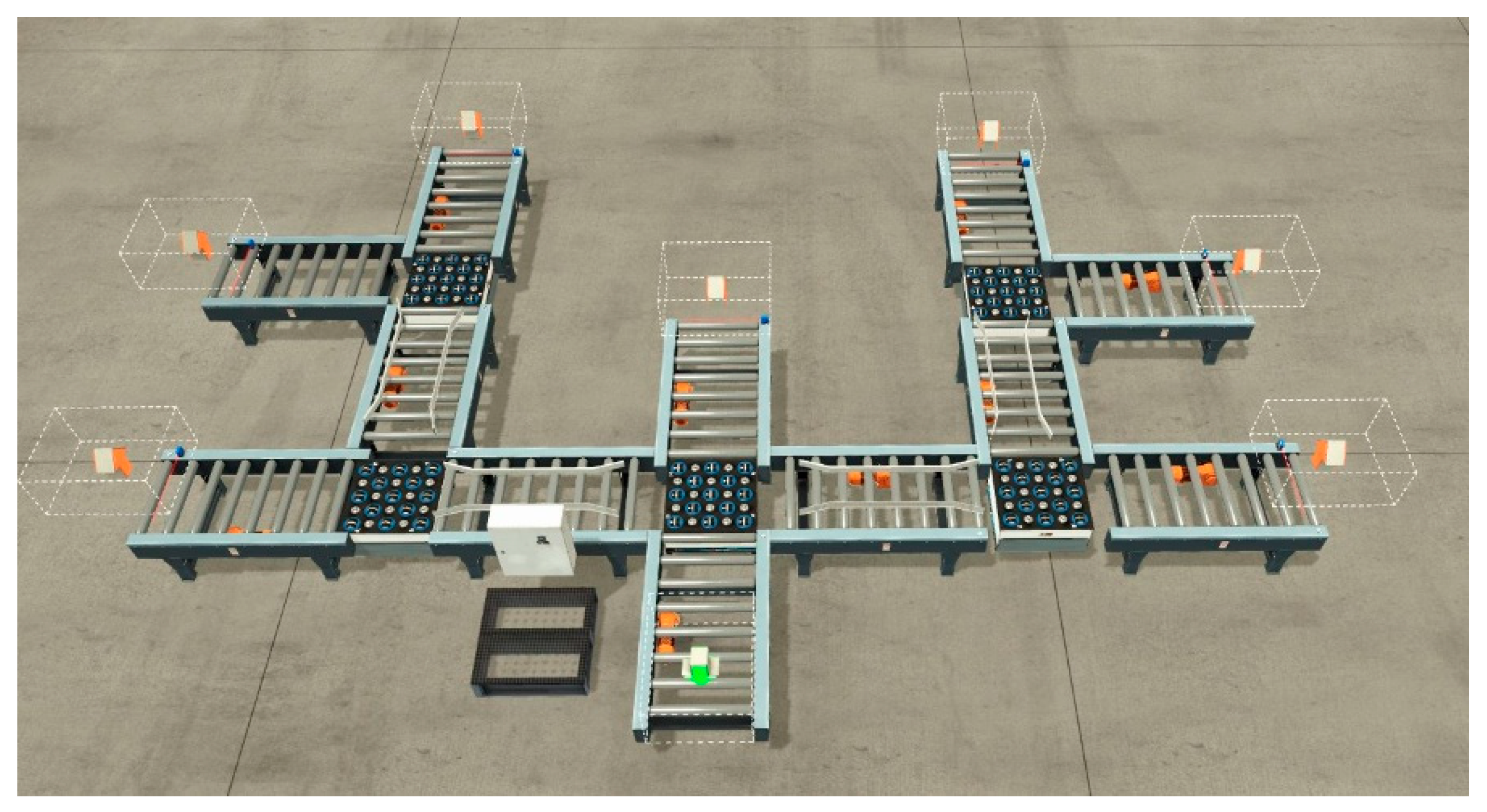

4. Model Environment

5. Expectations

- Structured Input—Parse and preprocess the natural language prompt

- Rule Decomposition—Break down the command into logical subcomponents

- Logical Expression—Translate subcomponents into formal rules or expressions

- Question Answering—Resolve the intended user request based on logic

- Element Recomposition—Reconstruct the complete control instruction

- Expression Resolution—Generate the final register value for Modbus execution

- the registers are correct

- the values are as given for the storage unit

- the speed is correct

- due the Modbus write there was no problem or collision

∧

∧  ∧

∧  ∧

∧

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Washfy, T.M.; Noor, A.K. Rule-based natural-language interface for virtual environments. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2002, 33, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.S. Advancements in natural language processing for automotive virtual assistants enhancing user experience and safety. J. Comput. Intell. Robot. 2023, 3, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; He, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Han, Q.L.; Tang, Y. A brief overview of ChatGPT: The history, status quo and potential future development. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introducing LLaMA: A Foundational, 65-Billion-Parameter Large Language Model. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/large-language-model-llama-meta-ai/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Gao, T.; Fisch, A.; Chen, D. Making pre-trained language models better few-shot learners. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 3816–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.H.; Stringer, P.G. An autosynthesizing non-linear control system using a rule-based expert system. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 1991, 5, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.; Lacroix, T.; Roziere, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 22), New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Servantez, S.; Barrow, J.; Hammond, K.; Jain, R. Chain of logic: Rule-based reasoning with large language models. Findings Assoc. Comput. Linguist. ACL 2024, 2024, 2721–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Axmed, M.; Pryzant, R.; Khani, F. Prompt engineering a prompt engineer. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2311.05661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, L.S. The art and science of prompt engineering: A new literacy in the information age. Internet Ref. Serv. Q. 2023, 27, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Jazdi, N.; Zhang, J.; Shah, C.; Weyrich, M. Control industrial automation system with large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.18009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, M.G. Design and implementation of PLC-based monitoring control system for induction motor. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2004, 19, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.S.; Mohammed, K.G.; Al-sagar, Z.S.; Sameen, A.Z. Design and implementation of PLC-based monitoring and sequence controller system. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2018, 10, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yasunaga, M.; Yang, D. Is ChatGPT a general-purpose natural language processing task solver? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.06476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifan, M.; Ionescu, B.; Ionescu, D. A real time self-generating control for AI platforms. In Proceedings of the IEEE 18th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI), Siófok, Hungary, 21–25 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JSON—Introduction. Available online: https://www.w3schools.com/js/js_json_intro.asp (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Kochmar, E. Getting Started with Natural Language Processing; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781617296765. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Banerjee, A.; Demiralp, C.; Durrett, G.; Dillig, I. Data extraction via semantic regular expression synthesis. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2023, 7, 1848–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, I.; Lampinen, A.K.; Chan, S.C.Y.; Creswell, A.; Kumaran, D.; McClelland, J.L.; Hill, F. Language models show human-like content effects on reasoning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.07051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D.D.L.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2303.15556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | User Prompt | Answer | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Take the box to 1 storage unit with 55% (voice) | Register 0<- 32779 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 1 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 11<- 5500 | Speed is incorrect | ||

| 2. | Vidd a dobozt az 1-es tárolóhelyre, 55%-os sebességgel | Register 0<- 32779 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 1 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 80<- 5500 | Speed is incorrect | ||

| 3. | Vidd az 1-es tárhelyre, 55%-al | Register 0<- 32779 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 1 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 137 | Speed is incorrect | ||

| 4. | Take the box to second store at 89% speed (voice) | Register 0<- 33003 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 6 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 89 | Speed is correct | ||

| 5. | Vidd a dobozt az 2-es tárolóhelyre, 89%-es sebességgel | Register 0<- 33003 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 6 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 89 | Speed is correct | ||

| 6. | Vidd az 2-es tárhelyre, 89%-al | Register 0<- 33003 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 6 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 89 | Speed is correct | ||

| 7. | Take the box to 3rd storage unit at 22% speed (voice) | Register 0<- 32875 | Registers are incorrect |

| Register 1<- 10 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 80 | Speed is incorrect | ||

| 8. | Vidd a dobozt az 3-as tárolóhelyre, 22%-os sebességgel | Register 0<- 32875 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 10 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 55 | Speed is incorrect | ||

| 9. | Vidd az 3-as tárhelyre, 22%-al | Register 0<- 32875 | Registers are correct |

| Register 1<- 10 | Values are correct | ||

| Register 12<- 17 | Speed is incorrect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kernács, M.; Hornyák, O. Supporting Rule-Based Control with a Natural Language Model. Eng. Proc. 2025, 113, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113056

Kernács M, Hornyák O. Supporting Rule-Based Control with a Natural Language Model. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 113(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113056

Chicago/Turabian StyleKernács, Martin, and Olivér Hornyák. 2025. "Supporting Rule-Based Control with a Natural Language Model" Engineering Proceedings 113, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113056

APA StyleKernács, M., & Hornyák, O. (2025). Supporting Rule-Based Control with a Natural Language Model. Engineering Proceedings, 113(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025113056