1. Introduction

Robotic systems designed for human interaction and autonomous decision-making represent a fascinating area of research. Simple board games like Tic-Tac-Toe serve as effective testbeds for evaluating control strategies and decision-making algorithms in physical environments due to their finite and straightforward rules.

Recent advancements in vision-based robotic applications have been comprehensively reviewed in [

1], highlighting the evolution of robotic manipulation through the incorporation of sensors and artificial intelligence, or in [

2], where specific Artificial Intelligence-based applications and usage are presented, from control to simulations. These systems rely heavily on computer vision to interpret and interact with their environment, employing various machine learning, deep learning, or reinforcement learning models for processing visual data and making informed decisions [

3]. The application of deep learning in real-time object detection has further improved the efficiency and accuracy of robotic perception in dynamic settings [

4].

Various approaches and technologies have been employed in developing real-time robotic systems capable of playing games, many of which are based on computer vision architectures. Platforms that can play Tic-Tac-Toe encompass aspects such as swarm robotics with reinforcement learning [

5,

6], humanoid robot interaction [

7], and innovative input methods that demonstrate the potential for more natural and accessible human–robot interactions in gaming scenarios [

8,

9].

This paper presents a robotic XY plotter designed to play real-time Tic-Tac-Toe against a human opponent. The robot utilizes stepper motors, CNC modules, and a microcontroller embedded board for precise control [

10]. Computer vision processes visual input from cameras to determine the player’s move, while game logic follows the Minimax algorithm—a well-established decision-making method based on recursive state evaluation and optimization rules. This study emphasizes the preference for mathematically structured algorithms over artificial intelligence models for reliable critical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

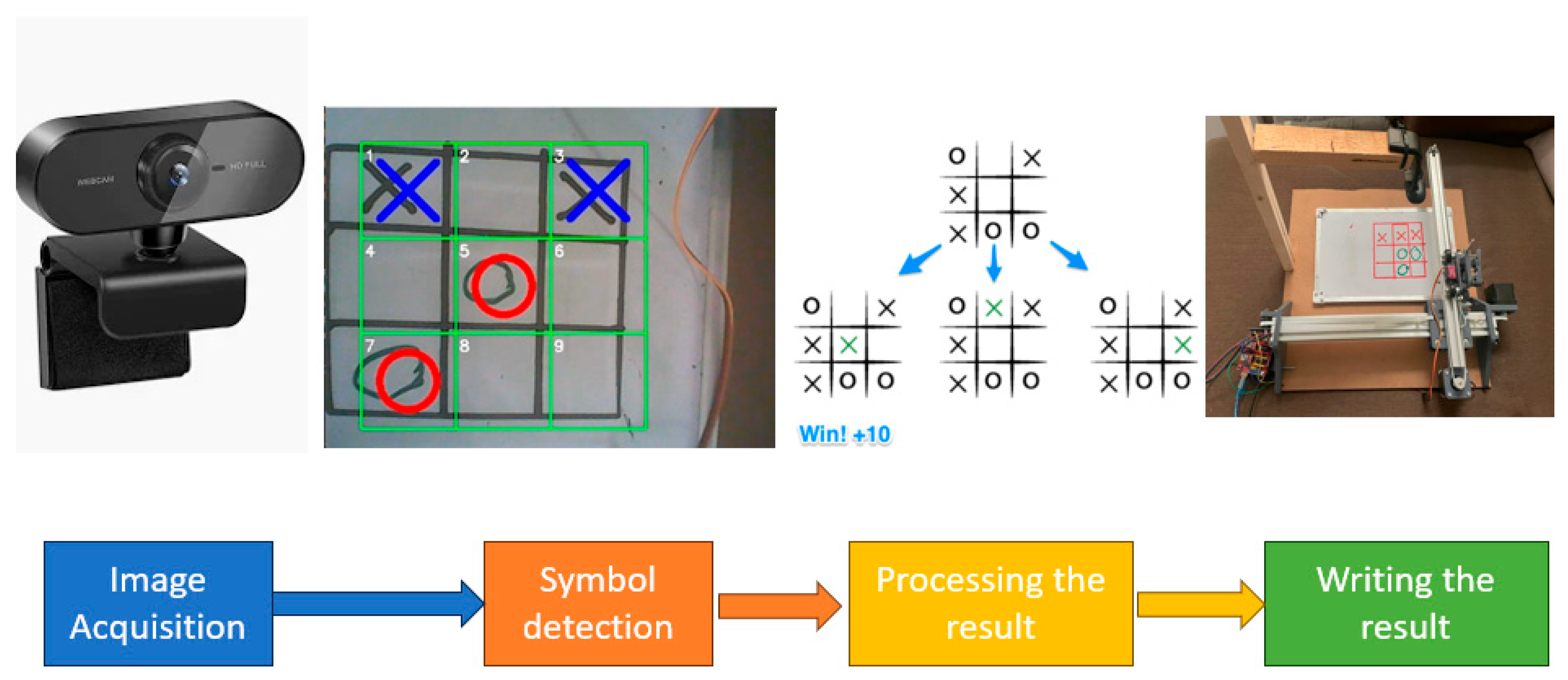

The proposed real-time Tic-Tac-Toe system is designed as an integrated pipeline that combines visual perception, game state analysis, strategic decision-making, and robotic actuation. The methodology centers on four core functional modules: image acquisition via a camera system, symbol detection through structured image processing, optimal move selection using the Minimax algorithm, and execution of the selected move by a 2D robotic plotter.

We used an Arduino Uno Rev 3 (Arduino, Ivrea, Italy) runing GRBL, two Wantai NEMA-17 stepper motors (Shenzhen, China) driven by a SainSmart CNC shield (Shenzhen, China) with Pololu A4988 driver modules (Las Vegas, NV, USA), commanded via USB from a Python script. The GRBL is implemented in C++, in Arduino IDE.

The structure is built with aluminum rails and 3D-printed parts for the pen carriage.

A USB camera captures the board image. Image processing is performed in Python 3.10 with OpenCV 4.12.0, using grayscale conversion, Gaussian blur, and Hough Circle Transform for detecting the symbols.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the process begins with the camera capturing a live image of the game board. This image is analyzed to detect player inputs—specifically the placement of

and

symbols—within a predefined structured frame, ensuring an accurate and real-time digital representation of the board state.

Based on the recognized configuration, the Minimax algorithm computes the optimal move by simulating possible outcomes to maximize the system’s chances of winning or drawing.

2.1. Detection of Player Inputs

Accurate recognition of the opponent’s moves is essential for enabling the system to respond appropriately during gameplay. The current implementation focuses on detecting only the

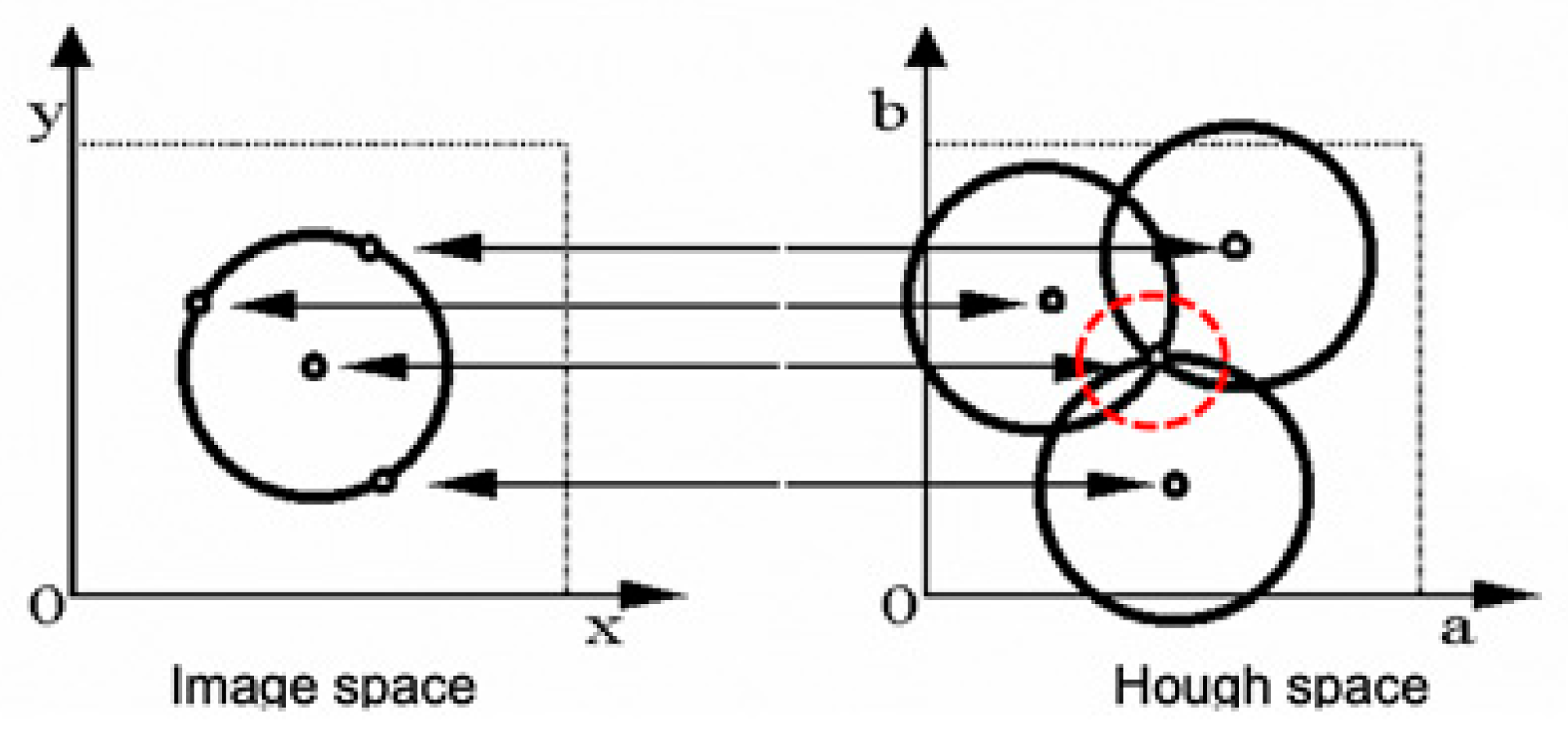

symbol, which is characterized by its circular shape and can be reliably identified using a circle detection algorithm based on the Hough Transform [

11].

Preprocessing begins with converting the captured RGB image

into a grayscale image

, followed by smoothing to suppress noise and enhance edge continuity. A Gaussian filter

is applied, defined as:

where

is the standard deviation controlling the level of smoothing, and

are the pixel coordinates. The filtered image

is obtained via convolution, as follows:

Following this, edges in the image are detected and passed to a circular Hough Transform algorithm. The Hough Transform for circles maps edge points from the image space into a 3D parameter space of possible circles defined by their center

and radius

(see

Figure 2). For each edge point

, the transform evaluates all possible circles passing through that point using the parametric equation of a circle:

Each valid tuple casts a vote in an accumulator space. Circles in the image correspond to local maxima (peaks) in this space.

To reduce false positives, only circles within a specified radius range are considered. Additional post-processing steps verify that the detected circles align with the physical tic-tac-toe grid, ensuring consistency with valid symbol positions.

This method provides high detection accuracy for circular symbols and is relatively robust to moderate image noise. However, it requires careful tuning of parameters such as , and threshold values for edge detection and accumulator voting. A key limitation is that it does not support non-circular symbols, constraining the system to games in which the human player uses only the symbol.

Currently, the vision module detects only ‘O’ symbols using circle detection. This constraint simplifies processing but limits full two-player support. Extending the system to detect symbols using template matching or edge-based shape descriptors is part of future work.

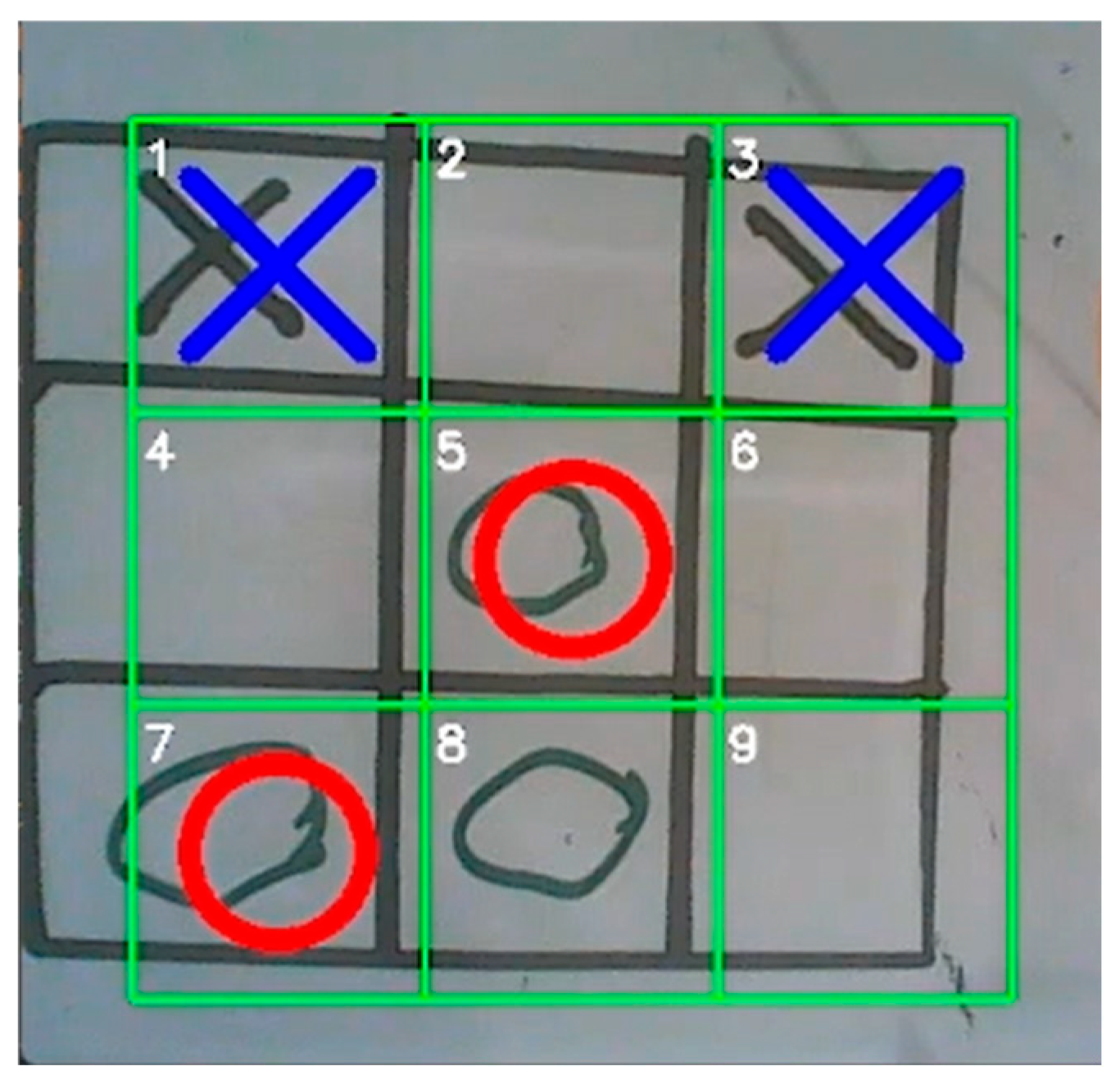

An example gameplay frame is shown in

Figure 3, where detected

symbols are highlighted in red,

symbols are shown in blue, and the tic-tac-toe grid is outlined in green.

2.2. Decision Making Using the Minimax Algorithm

To ensure optimal gameplay in a two-player mode, the decision-making component of the system utilizes the Minimax algorithm [

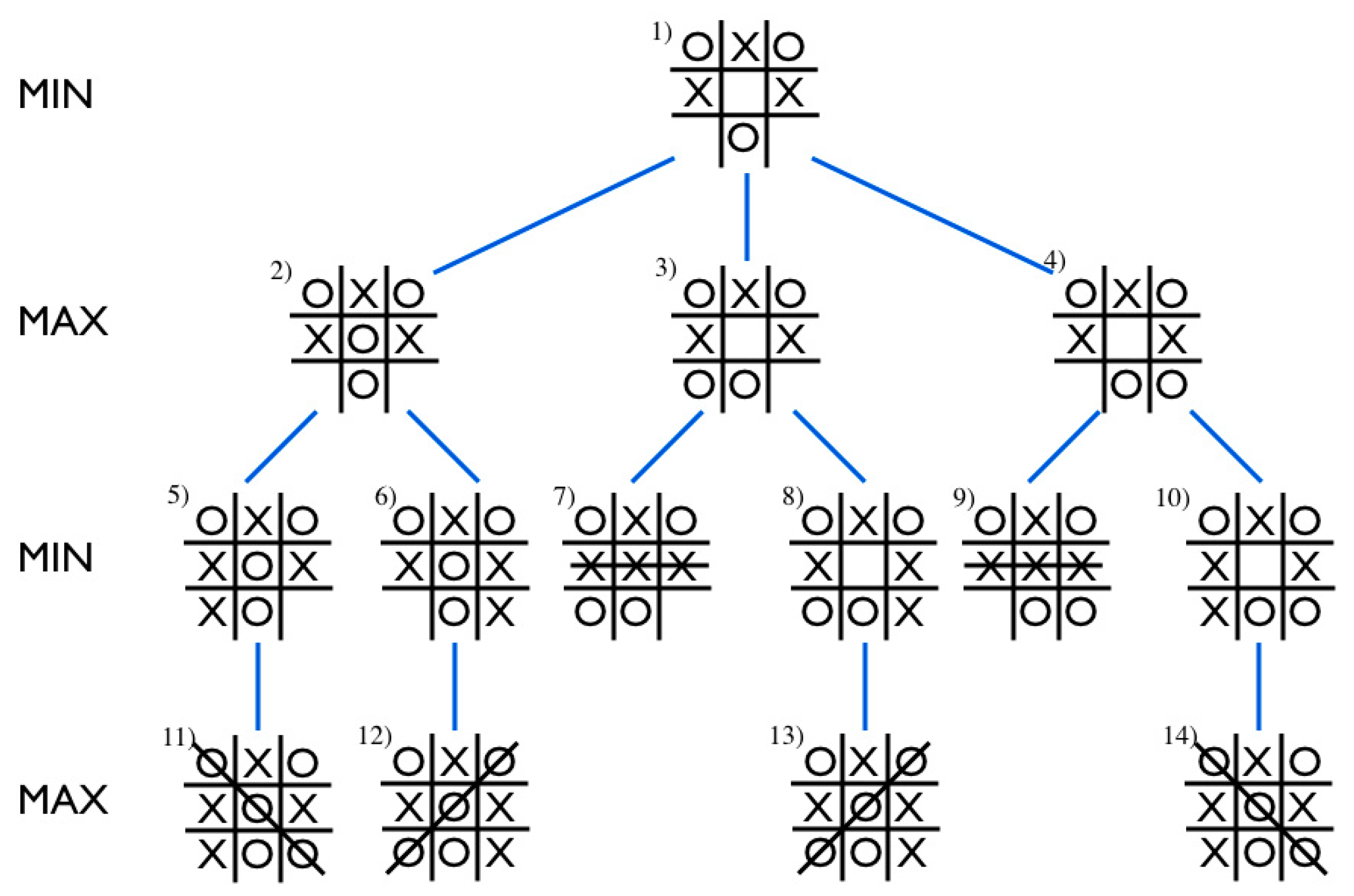

12]. This algorithm systematically explores all possible future game states to determine the move that maximizes the chance of winning or drawing for the computer-controlled player. Given the relatively low complexity and finite number of states in Tic-Tac-Toe, Minimax provides a complete and computationally feasible solution without the need for probabilistic or learning-based approaches.

The current game state is represented as a square matrix , where each element can take one of the following values: is an empty cell, is the cell occupied by player (maximizing player), and is the cell occupied by player (minimizing player).

An evaluation function is defined to assess the utility of a board configuration from the perspective of the maximizing player. The function returns: a positive value (e.g., ) if wins, a negative value (e.g., ) if wins, and zero if the game is a draw or still in progress without a decisive outcome.

The Minimax procedure operates recursively as follows:

- (a)

The Minimization step (Player ): For each valid move in the current state , generate a successor state and evaluate it using the Minimax function from the minimizing player’s (′s) perspective. The maximizing player chooses the move that yields:

- (b)

The Minimization step (Player ): Conversely, the minimizing player selects the move that minimizes the value propagated by the maximizing player:

This alternating maximization and minimization continues recursively through the game tree until a terminal state is reached or a predefined search depth is exceeded. Terminal conditions include a winning configuration (three aligned symbols), a full board (draw), or other stopping rules to limit recursion.

Due to the small and finite state space of Tic-Tac-Toe (fewer than distinct game states), the Minimax algorithm can fully evaluate the game tree in real time. This guarantees optimal play from the system, ensuring that it never loses when playing as the maximizing player and can always force a draw at minimum.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the Minimax algorithm recursively explores the full game tree. At each level, the active player selects the move that optimizes the game outcome based on the evaluations of possible future states. In this example, the optimal move for the maximizing player (

) is determined to be the center position, with a propagated value of

.

3. Results

The experimental evaluation considers a comparative analysis of the performance of the Minimax algorithm and an AI method based on neural networks (reinforcement learning) in playing Tic-Tac-Toe [

13]. A reinforcement learning agent was implemented by Q-learning. The state space included all possible 3 × 3 board configurations encoded as a flattened 9-element array. The action space contained the available cells in which a move could be made.

This training involved 1000 episodes of self-play. The agent received +1 for winning, −1 for losing, and 0 for a draw.

We use important performance metrics such as computation time, number of evaluated nodes, and move optimality to illustrate the Minimax approach efficiency in this application.

The Minimax algorithm consistently provided optimal moves with an average decision time of 15 ms per move. In 50 games played using the Minimax algorithm, 36 games ended in a draw, 14 games were won by the system, and none were lost. Each algorithm (Minimax and RL) was evaluated over 50 games. For consistency, a fixed opponent strategy was defined: the opponent played using a handcrafted rule-based strategy that prioritizes center → corners → sides.

To avoid redundancy due to board symmetries, we generated starting positions representative of distinct gameplay patterns, such as center-first, edge-first, and corner-first openings. Every game was initialized with a randomized but valid player start to ensure diversity.

Conversely, the AI method showed longer decision times, averaging around 40 ms per move, and resulted in 23 draws, 15 wins, and 12 losses out of 50 games. From 50 games played using the AI algorithm, the results we obtained are as follows: 23 games draw, 15 games won, and 12 games lost by the proposed system.

Several patterns emerge from the data. The Minimax algorithm’s shorter decision time correlates with its higher efficiency and reliability in gameplay, consistently providing optimal moves and resulting in a higher number of draws and wins. The AI method’s longer decision time correlates with its occasional suboptimal moves and higher number of losses, suggesting variability in its performance.

The findings support the paper’s thesis that mathematically structured algorithms, such as the Minimax algorithm, provide more predictable, reliable, and secure outcomes compared to AI models for simple applications like Tic-Tac-Toe. The Minimax algorithm’s consistent performance and lower computational requirements validate its suitability for tasks requiring precise calculations.

4. Discussion

The Minimax algorithm was first introduced by John von Neumann in his seminal 1928 paper Zur Theorie der Gesellschaftsspiele [

14], laying the foundation for game theory. Later developments include its application in computer chess (e.g., IBM’s Deep Blue) and its influence on modern decision algorithms like Monte Carlo Tree Search and reinforcement learning.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized numerous industries, bringing efficiency, automation, and innovative solutions to complex problems. From medical diagnostics to autonomous vehicles, AI has enabled advancements that were once thought impossible. However, in certain simple applications, relying on AI might not always be necessary. Traditional mathematical algorithms often provide more predictable, reliable, and secure outcomes, particularly in fields where precise calculations are required.

This study compares the performance of the Minimax algorithm with an AI method based on neural networks (reinforcement learning) in the context of playing Tic-Tac-Toe. The results demonstrate significant differences in decision-making efficiency, computational requirements, and reliability between these approaches:

Decision-making efficiency: the Minimax algorithm consistently operates within a 10–15 ms range, ensuring rapid decision-making. Alternative AI methods exhibit a much wider distribution around 40 ms, indicating longer computation times due to the overhead of inference and data preprocessing.

Performance consistency: the Minimax strategy never made a suboptimal move, guaranteeing optimal play and a high win/draw ratio. The alternative AI occasionally deviated, resulting in suboptimal moves that affected its performance.

Training requirements: the Minimax algorithm requires no training and can be used directly, providing immediate and reliable results. AI methods rely heavily on training; when the model is not fully trained, it may make suboptimal moves that result in losses or drawn games.

Unlike AI, which operates on probabilistic models, a well-defined mathematical algorithm ensures deterministic results without unexpected variations. This makes mathematical algorithms more dependable for straightforward tasks where precise calculations are essential. The Minimax algorithm’s exhaustive search capability and low computational requirements make it particularly suitable for Tic-Tac-Toe, a game with a constrained state space. Mathematical algorithms provide consistent performance and outcome guarantees, making them ideal for applications requiring high reliability. AI excels at handling ambiguity and adapting to new data, but its probabilistic nature can introduce uncertainties in simple, deterministic tasks.

The lower performance of AI-based methods may be due to inadequate training time or low network complexity. These may impair the generalization ability of the model across board states, especially in late-game situations when optimal play depends on early moves.

Thus, traditional algorithms such as Minimax are much more efficient for simple games like Tic-Tac-Toe since they guarantee optimal play without large computational requirements nor long training times. In addition, non-AI methods avoid the added complexity and low robustness of under-trained AI models by providing a clear, fast and precise solution.

The findings support the choice of the Minimax algorithm for the Tic-Tac-Toe system, highlighting its efficiency and reliability. Future research could explore the integration of machine learning algorithms for more complex games or applications where adaptability and learning are crucial. While it is theoretically expected that the deterministic Minimax algorithm outperforms a learning-based method in a constrained and fully solvable game such as 3 × 3 Tic-Tac-Toe, the contribution of this study lies in the empirical validation of this assumption within a real-time robotic system.

Additionally, further studies could investigate hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of mathematical algorithms and AI to optimize performance in various contexts. The study demonstrates potential applications in automation, education, and interactive entertainment. The reliability and efficiency of the Minimax algorithm make it suitable for critical applications where precise calculations are essential.

5. Conclusions

This article presents the design and implementation of an XY plotter system capable of playing Tic-Tac-Toe against a human opponent. By integrating stepper motors, a microcontroller, and a CNC module, the system achieves precise bidirectional movement. The use of a vision-based algorithm for detecting user moves, combined with the Minimax strategy for optimal decision-making, demonstrates the effectiveness of mathematically structured algorithms in ensuring reliable and predictable outcomes.

While the study focuses on Tic-Tac-Toe, the results suggest that deterministic algorithms like Minimax may be well-suited for other structured tasks such as turn-based logic puzzles, calibration routines, or deterministic industrial workflows where exhaustive search is feasible and outcomes must be predictable.

The experimental results validate the system’s accuracy and efficiency in real-time gameplay scenarios. The Minimax algorithm consistently provided optimal moves with minimal computation time, outperforming an alternative AI method based on neural networks. This highlights the advantages of deterministic algorithms over probabilistic AI models for tasks requiring consistent performance and outcome guarantees.

The study underscores the potential applications of such systems in automation, education, and interactive entertainment. The reliability and efficiency of the Minimax algorithm make it suitable for critical applications where precise calculations are essential. Additionally, the integration of robotics and human–computer interaction opens new avenues for developing interactive systems that enhance user experience and engagement.

Future research could explore the integration of machine learning algorithms for more complex games or applications where adaptability and learning are crucial. Further studies could also investigate hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of mathematical algorithms and AI to optimize performance in various contexts.

This work demonstrates the successful application of a mathematically structured approach to a real-time interactive system, providing a foundation for future developments in the field of robotics and human–computer interaction. The findings support the continued use of deterministic algorithms for simple, well-defined tasks, while also encouraging the exploration of more advanced AI techniques for complex and dynamic applications.