Assessment of Drought Vulnerability in Faisalabad Through Remote Sensing and GIS †

Abstract

1. Introduction

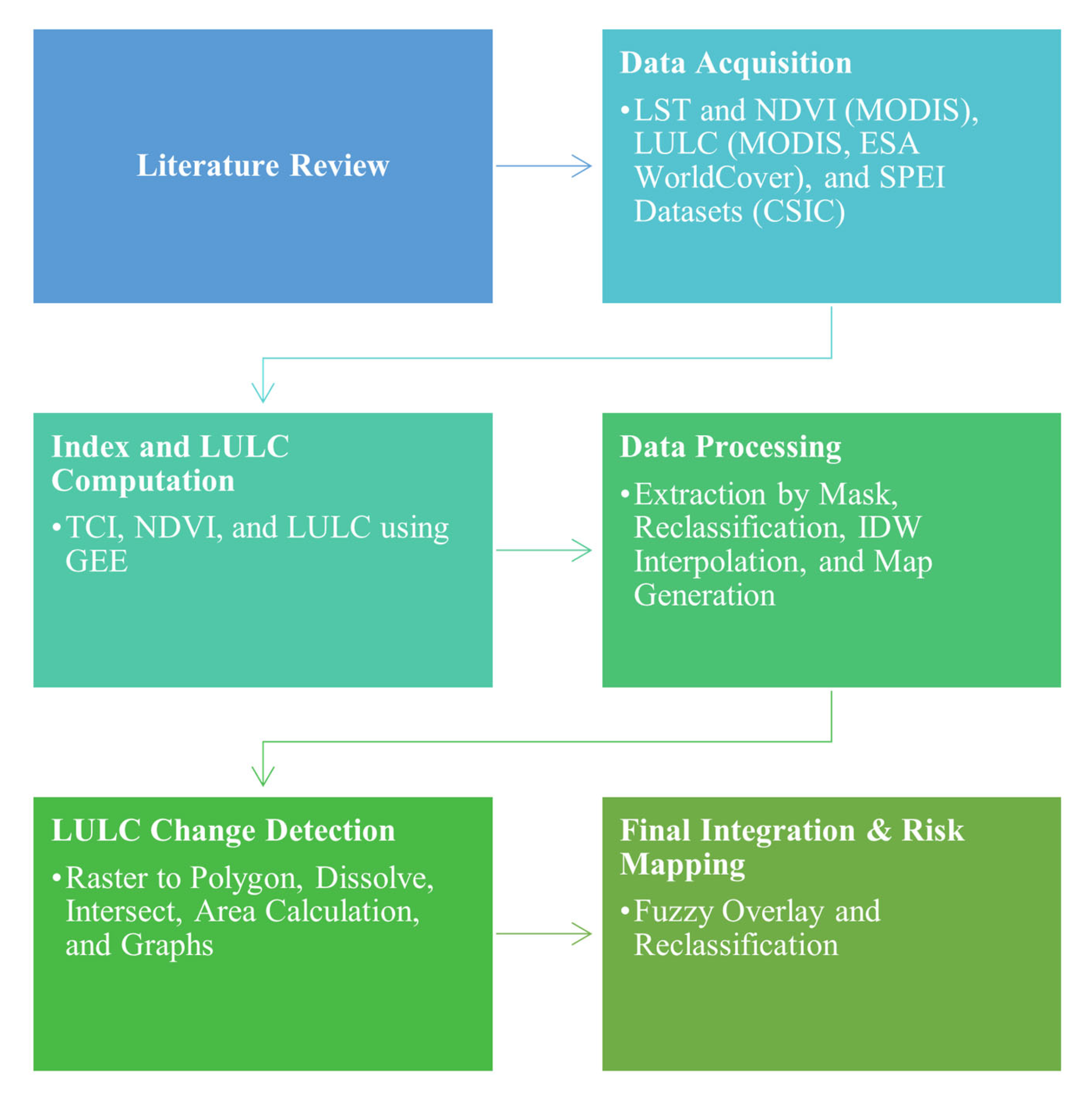

2. Methodology

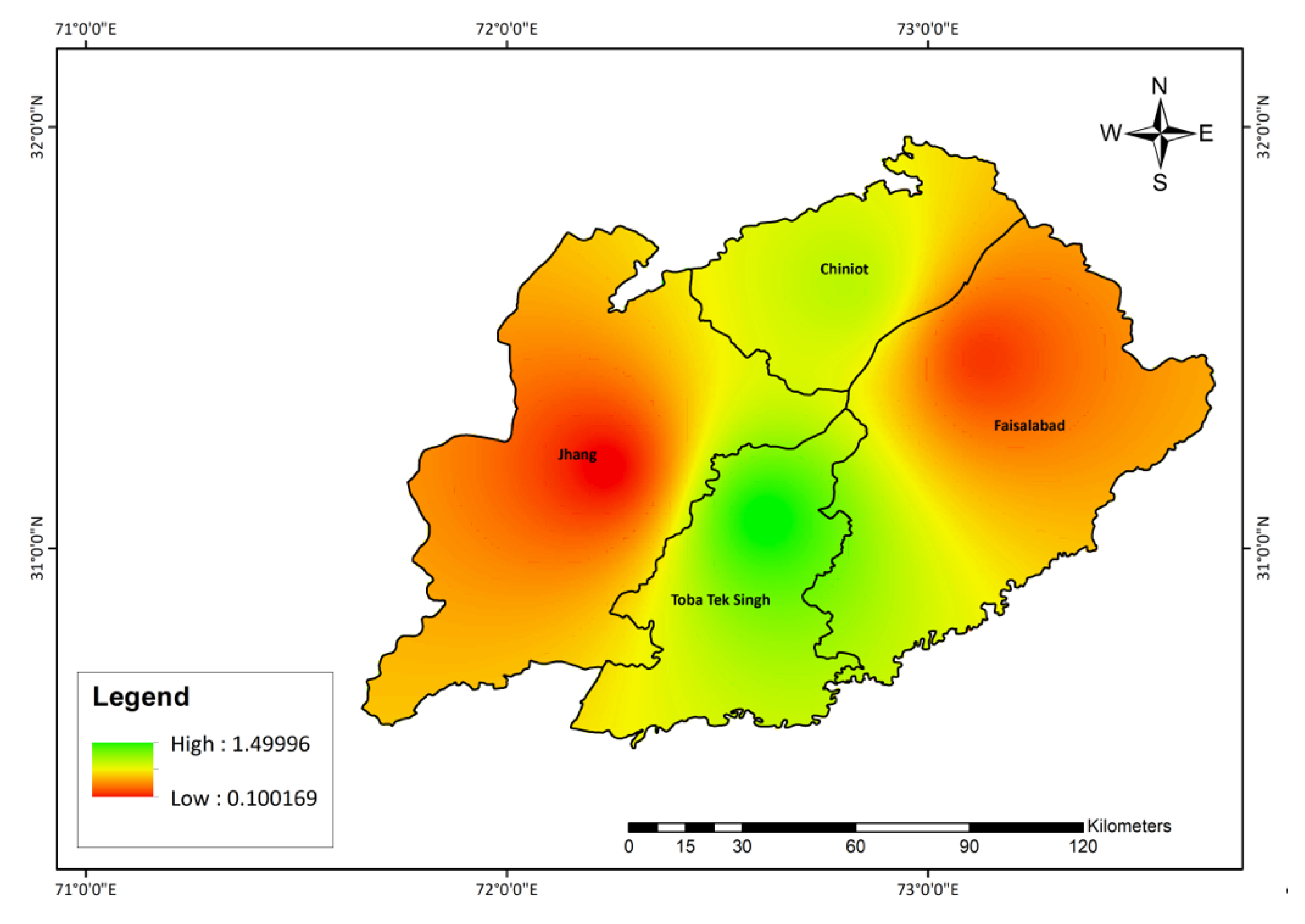

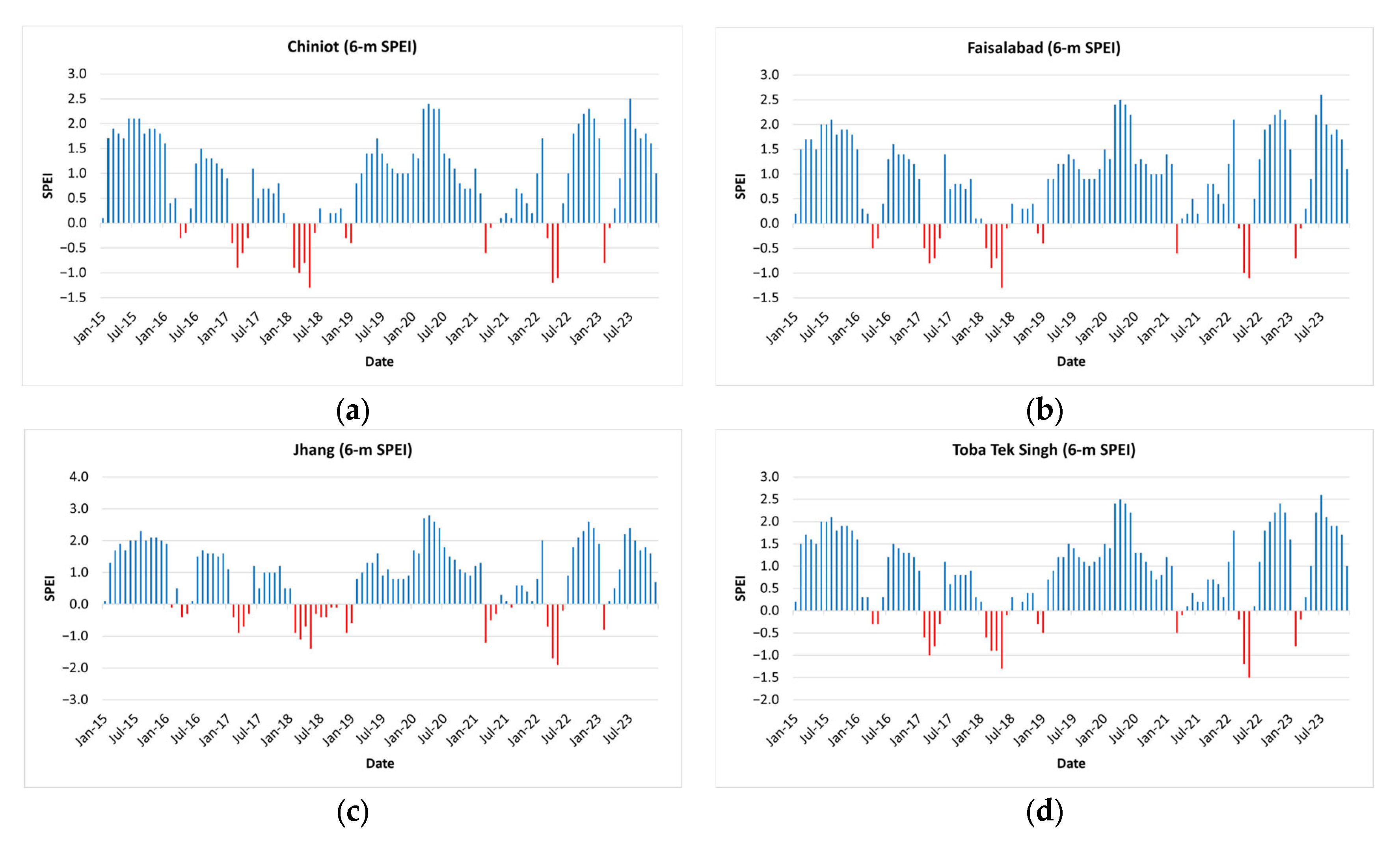

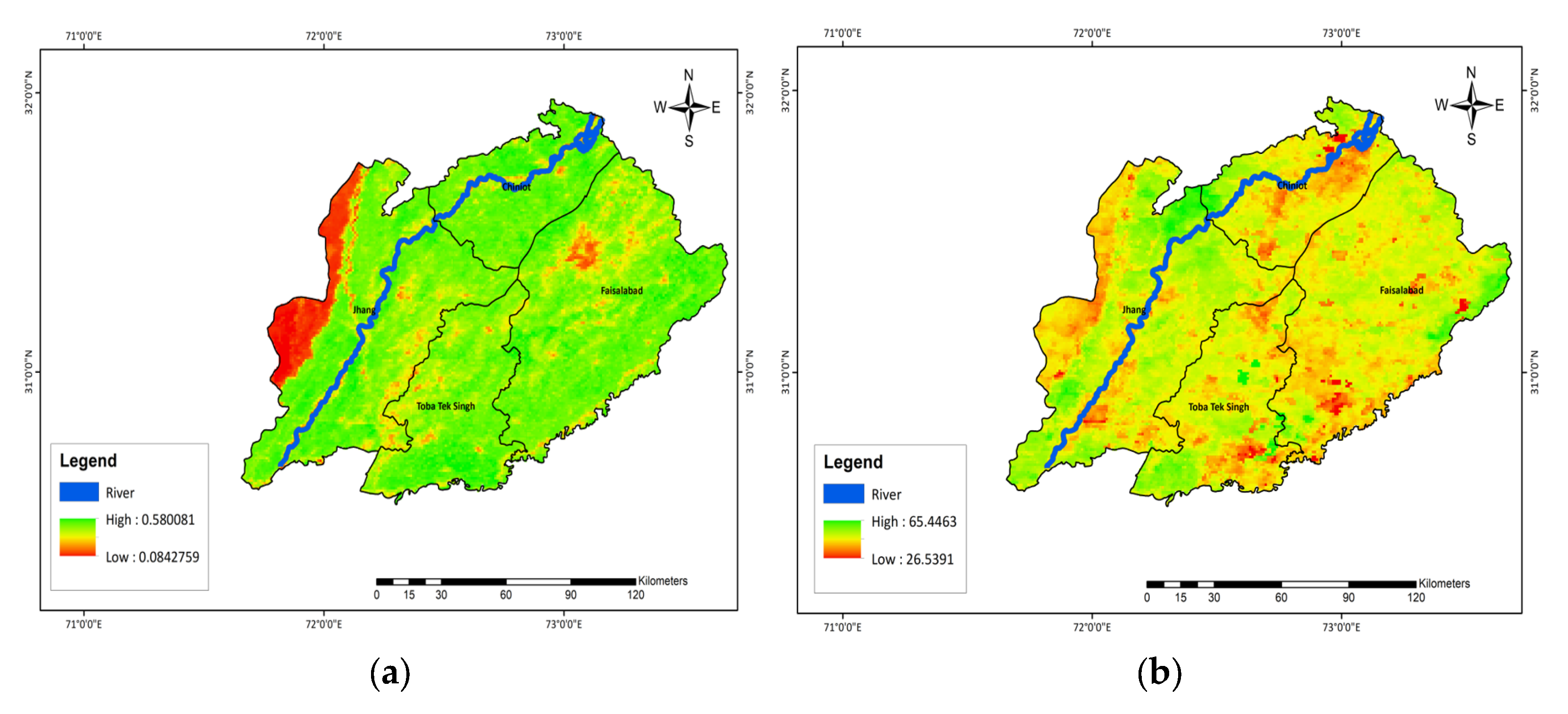

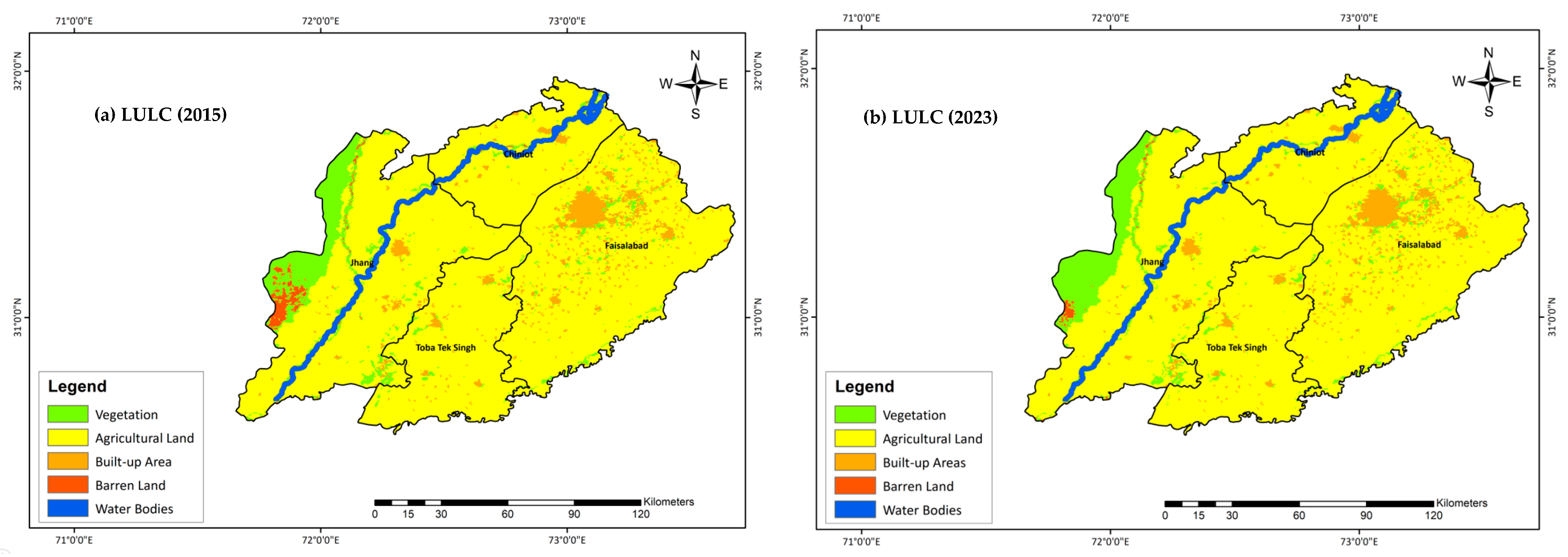

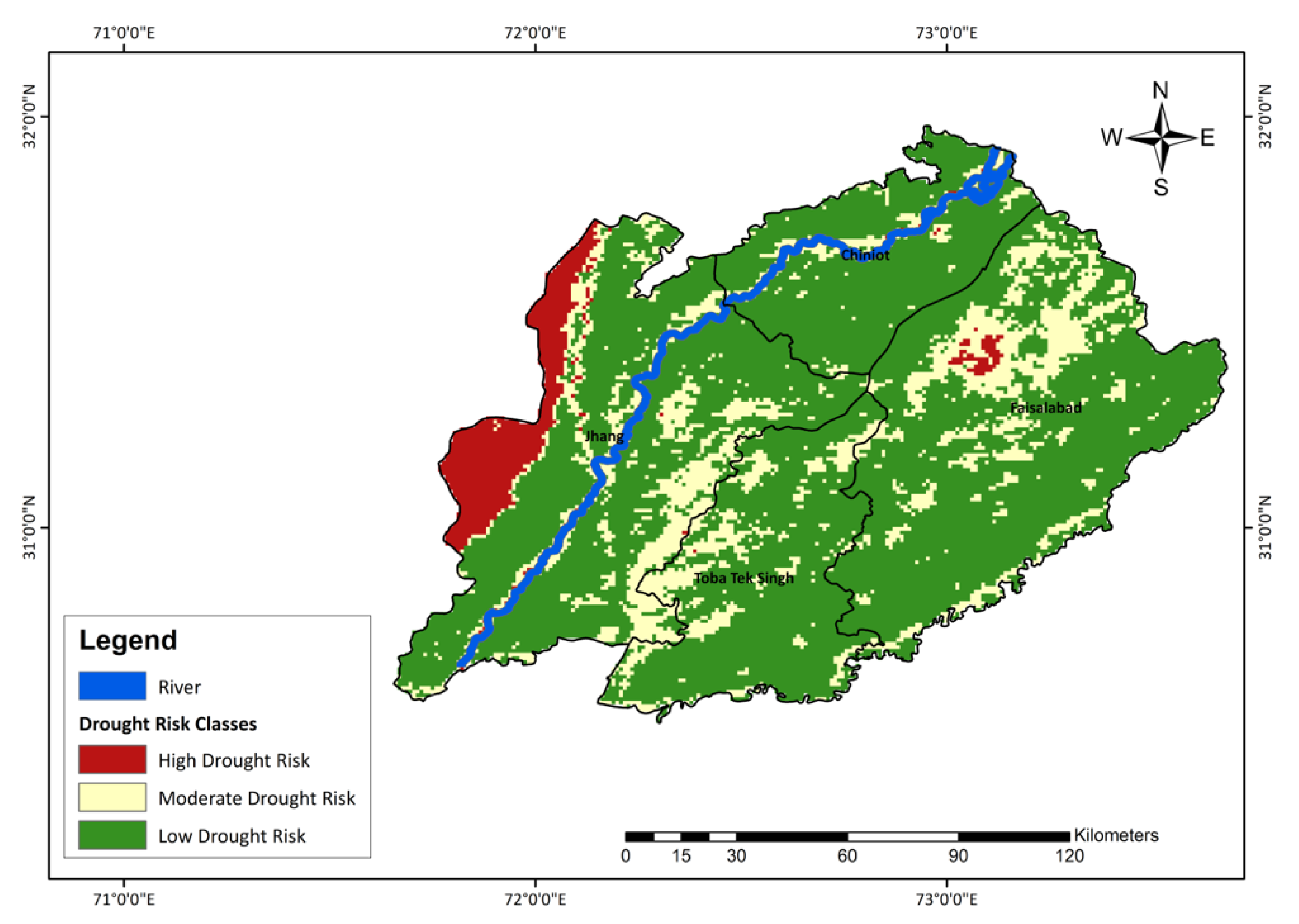

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, W.; Hashmi, M.Z.; Jamil, A.; Rasheed, S.; Akbar, S.; Iqbal, H. Mid-century change analysis of temperature and precipitation maxima in the Swat River Basin, Pakistan. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 973759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtak, K.; Wolińska, A. The impact of extreme weather events as a consequence of climate change on the soil moisture and on the quality of the soil environment and agriculture—A review. Catena 2023, 231, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Shukla, J., Skea, E., Calvo Buendia, V., Masson-Delmotte, H.-O., Pörtner, D.C., Roberts, P., Zhai, R., Slade, S., Connors, R., van Diemen, M., et al., Eds.; In press; 2019; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2019/11/SRCCL-Full-Report-Compiled-191128.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hina, S.; Saleem, F.; Arshad, A.; Hina, A.; Ullah, I. Droughts over Pakistan: Possible cycles, precursors and associated mechanisms. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 2021, 12, 1638–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Noreen, A.; Younas, T.; Khan, I.; Aziz, H.; Rehman, E.; Saleem, A.; Imam, M.F.; Saeed, A. Cropping pattern to cope with climate change scenario in Pakistan. Biosci. Res. 2022, 19, 957–963. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, H. Drought, farm output and heterogeneity: Evidence from Pakistan. J. South Asian Dev. 2022, 17, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goheer, M.A.; Aftab, B.; Farah, H.; Hassan, S.S. Spatio-temporal risk analysis of agriculture and meteorological droughts in rainfed Potohar, Pakistan, using remote sensing and geospatial techniques. Meteorol. Appl. 2023, 30, e2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, Z. Environmental pollution and regulatory and non-regulatory environmental responsibility (reviewing Pakistan environmental protection act). Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2023, 13, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Khan, M.R.; Hassan, S.S.; Khan, A.A.; Imran, M.; Goheer, M.A.; Hina, S.M.; Perveen, A. Monitoring agricultural drought using geospatial techniques: A case study of Thal region of Punjab, Pakistan. J. Water Clim. Change 2020, 11, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMD. Drought Bulletin of Pakistan: January–March 2013; National Drought Monitoring Centre, PMD: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2013. Available online: https://www.pmd.gov.pk/ndmc/quater1.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Khan, M.A.; Tahir, A.; Khurshid, N.; Husnain, M.I.; Ahmed, M.; Boughanmi, H. Economic effects of climate change-induced loss of agricultural production by 2050: A case study of Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Khan, F.; Ullah, H.; Ali, S.; Hussain, A. Enhancing Drought Risk Assessment in the Punjab, Pakistan: A Copula-Based Modeling Approach for Future Projections. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2024, 63, 1207–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, B.; AghaKouchak, A.; Alizadeh, A.; Mousavi Baygi, M.; RMoftakhari, H.; Mirchi, A.; Anjileli, H.; Madani, K. Quantifying anthropogenic stress on groundwater resources. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AghaKouchak, A.; Farahmand, A.; Melton, F.S.; Teixeira, J.; Anderson, M.C.; Wardlow, B.D.; Hain, C.R. Remote sensing of drought: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 452–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Qi, X.; Wu, C. Precondition cloud and maximum entropy principle coupling model-based approach for the comprehensive assessment of drought risk. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, F.N. Application of vegetation index and brightness temperature for drought detection. Adv. Space Res. 1995, 15, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Reig, F.; Latorre, B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: Parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 3001–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Fan, H.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. NDVI-based spatial and temporal vegetation trends and their response to precipitation and temperature changes in the Mu Us Desert from 2000 to 2019. Water Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Hu, J.; Islam, A.R.; Eibek, K.U.; Nasrin, Z.M. A comprehensive statistical assessment of drought indices to monitor drought status in Bangladesh. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhong, W.; Pan, S.; Xie, Q.; Kim, T.W. Comprehensive drought assessment using a modified composite drought index: A case study in Hubei Province, China. Water 2020, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzar, M.K.; Shafiq, M.; Mahmood, S.A.; Irfan, M.; Khalil, T.; Khubaib, N.; Hamid, A.; Shaista, S. Drought Risk Assessment in the Khushab Region of Pakistan Using Satellite Remote Sensing and Geospatial Methods: Drought Risk Assessment in the Khushab Region of Pakistan Using Satellite Remote Sensing and Geospatial Methods. Int. J. Econ. Environ. Geol. 2019, 10, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, K.; Shahid, S.; Harun, S.B.; Wang, X.J. Characterization of seasonal droughts in Balochistan Province, Pakistan. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, S.; Ullah, K.; Gao, S.; Khosa, A.H.; Wang, Z. Shifting of agro-climatic zones, their drought vulnerability, and precipitation and temperature trends in Pakistan. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Lian, L.; Wu, T.; Wang, J.; Dong, F.; Wang, Y. Quantifying the effects of climate variability, land-use changes, and human activities on drought based on the SWAT–PDSI model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruda, A.; Kolejka, J.; Batelková, K. Geocomputation and spatial modelling for geographical drought risk assessment: A case study of the Hustopeče Area, Czech Republic. In Geoinformatics and Atmospheric Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dwomoh, F.K.; Brown, J.F.; Tollerud, H.J.; Auch, R.F. Hotter drought escalates tree cover declines in blue oak woodlands of California. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 689945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affram, G.; Zhang, W.; Hipps, L.; Ratterman, C. Characterizing the development and drivers of 2021 Western US drought. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 044040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, K. Risk assessment of drought in the Yangtze River Delta based on natural disaster risk theory. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2017, 2017, 5682180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenlocher, M.; Meza, I.; Anderson, C.C.; Min, A.; Renaud, F.G.; Walz, Y.; Siebert, S.; Sebesvari, Z. Drought vulnerability and risk assessments: State of the art, persistent gaps, and research agenda. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 083002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.M.; Burton, I. Using the adaptation policy framework to assess climate risks and response measures in south Asia: The case of floods and droughts in Bangladesh and India. In Climate Change and Water Resources in South Asia; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alamgir, M.; Mohsenipour, M.; Homsi, R.; Wang, X.; Shahid, S.; Shiru, M.S.; Alias, N.E.; Yuzir, A. Parametric assessment of seasonal drought risk to crop production in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, N.; Qureshi, N.N. City profile: Faisalabad, Pakistan. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2019, 10, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Urban Unit. Available online: https://urbanunit.gov.pk/Download/publications/Files/17/2023/Faisalabad%20Regional%20Development%20Plan%20-%20Urban%20Planning_compressed.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Mahmood, K.; HN, G. Urban development and sustainability milieu: A case study of Faisalabad City, Pakistan. Pak. J. Sci. 2023, 75, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.M.; Wang, J.; Abbas, H.; Ullah, I.; Khan, R.; Ali, F. Impact of climate and land-use change on groundwater resources, study of Faisalabad district, Pakistan. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Fan, H. Deriving drought indices from MODIS vegetation indices (NDVI/EVI) and Land Surface Temperature (LST): Is data reconstruction necessary? Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 101, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didan, K.; Barreto-Muñoz, A. MODIS Collection 6.1 (C61) Vegetation Index Product User Guide; University of Arizona, Vegetation Index and Phenology Lab: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2019. Available online: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/documents/621/MOD13_User_Guide_V61.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Ahmad, S.; Israr, M.; Ahmed, R.; Ashraf, A.; Amin, M.; Ahmad, N. Land use and cover changes in the Northern Mountains of Pakistan; a spatio-temporal change using MODIS (MCD12Q1) time series. Sarhad J. Agric. 2022, 38, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, C.; Nieto, R.; Linares, C.; Díaz, J.; Gimeno, L. Quantification of the effects of droughts on daily mortality in Spain at different timescales at regional and national levels: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyam, M.M.; Haque, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. Identifying the land use land cover (LULC) changes using remote sensing and GIS approach: A case study at Bhaluka in Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Su, F.; Liu, G.; Bridhikitti, A. Land cover mapping in cloud-prone tropical areas using Sentinel-2 data: Integrating spectral features with Ndvi temporal dynamics. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimabadi, P.D.; Khosravi, H.; Azarnivand, H.; Ahmadi, S. Assessment of the relationship between drought and vegetation cover using remote sensing. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2022, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.; Umar, M.; Mansha, M.; Khan, M.S.; Javed, M.N.; Gao, H.; Farhan, S.B.; Iqbal, I.; Abdullah, S. Assessment of drought conditions using HJ-1A/1B data: A case study of Potohar region, Pakistan. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk. 2018, 9, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.; Baig, M.A. Drought severity assessment in arid area of Thal Doab using remote sensing and GIS. Int. J. Water Resour. Arid Environ. 2011, 1, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. Rome. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2019. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/11f9288f-dc78-4171-8d02-92235b8d7dc7/content (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Aubrecht, C.; Özceylan, D. Identification of heat risk patterns in the US National Capital Region by integrating heat stress and related vulnerability. Environ. Int. 2013, 56, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, M.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, Y. Quantifying the cooling effect of river and its surrounding land use on local land surface temperature: A case study of Bahe River in Xi’an, China. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, V.; Caissie, D. Towards a better understanding of the evaporative cooling of rivers: Case study for the Little Southwest Miramichi River (New Brunswick, Canada). Can. Water Resour. J. 2023, 48, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J. Connecting Land and Water Planning in Colorado. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2024, 44, 1970–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Santhosh, D.T.; Ganavi, N.R.; Sarma, A.; Deori, C.; Das, J.; Kumar, S. A comprehensive review on greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture and evolving agricultural practices for climate resilience. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| District | Area (km2) | Total UCs | Urban UCs | Rural UCs | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faisalabad | 5856 | 346 | 157 | 189 | 31.4504 | 73.135 |

| Chiniot | 2643 | 39 | - | 39 | 31.6268 | 72.8043 |

| Jhang | 6166 | 91 | - | 91 | 31.1929 | 72.2364 |

| Toba Tek Singh | 3252 | 85 | - | 85 | 31.0685 | 72.6151 |

| Index | Type | Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| SPEI | Meteorological | Based on rainfall and PET |

| NDVI | Remote Sensing | Based on vegetation reflectance |

| TCI | Remote Sensing | Based on LST |

| Chiniot | Faisalabad | Jhang | Toba Tek Singh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiniot | 1.00 | |||

| Faisalabad | 0.99 | 1.00 | ||

| Jhang | 0.97 | 0.97 | 1.00 | |

| Toba Tek Singh | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rehman, E.U.; Sajid, L.; Naeem, Z. Assessment of Drought Vulnerability in Faisalabad Through Remote Sensing and GIS. Eng. Proc. 2025, 111, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025111034

Rehman EU, Sajid L, Naeem Z. Assessment of Drought Vulnerability in Faisalabad Through Remote Sensing and GIS. Engineering Proceedings. 2025; 111(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025111034

Chicago/Turabian StyleRehman, Ebadat Ur, Laiba Sajid, and Zainab Naeem. 2025. "Assessment of Drought Vulnerability in Faisalabad Through Remote Sensing and GIS" Engineering Proceedings 111, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025111034

APA StyleRehman, E. U., Sajid, L., & Naeem, Z. (2025). Assessment of Drought Vulnerability in Faisalabad Through Remote Sensing and GIS. Engineering Proceedings, 111(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2025111034