Comparison Between the Volatile Compounds of Essential Oils Isolated from Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus L.) and Its Antioxidant Capacity from Ecuadorian Highlands †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. Sample Preparation and Extraction

2.3. Physicochemical Parameters

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. Determination of Volatiles

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

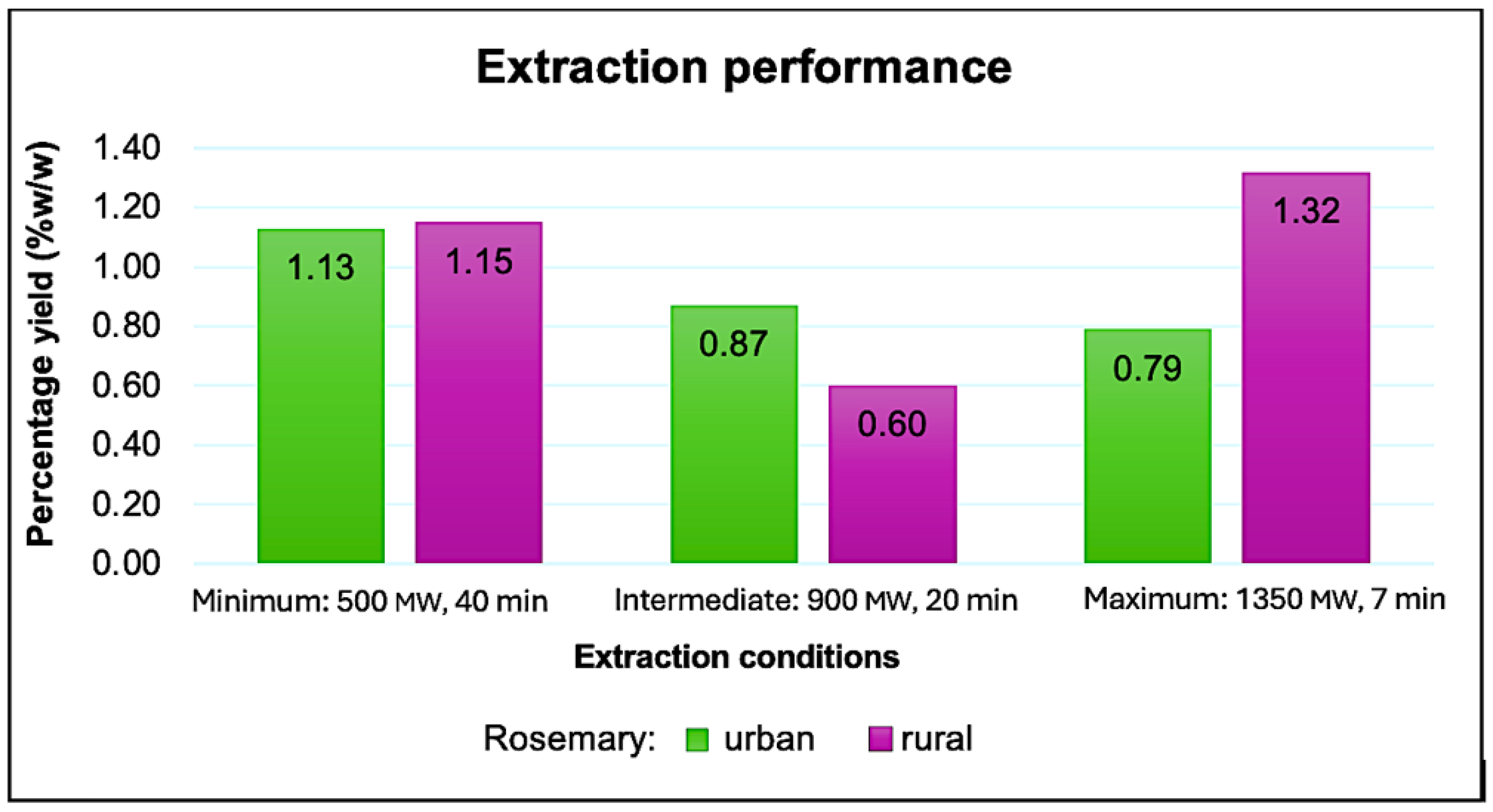

3.1. Oil Extraction Yield

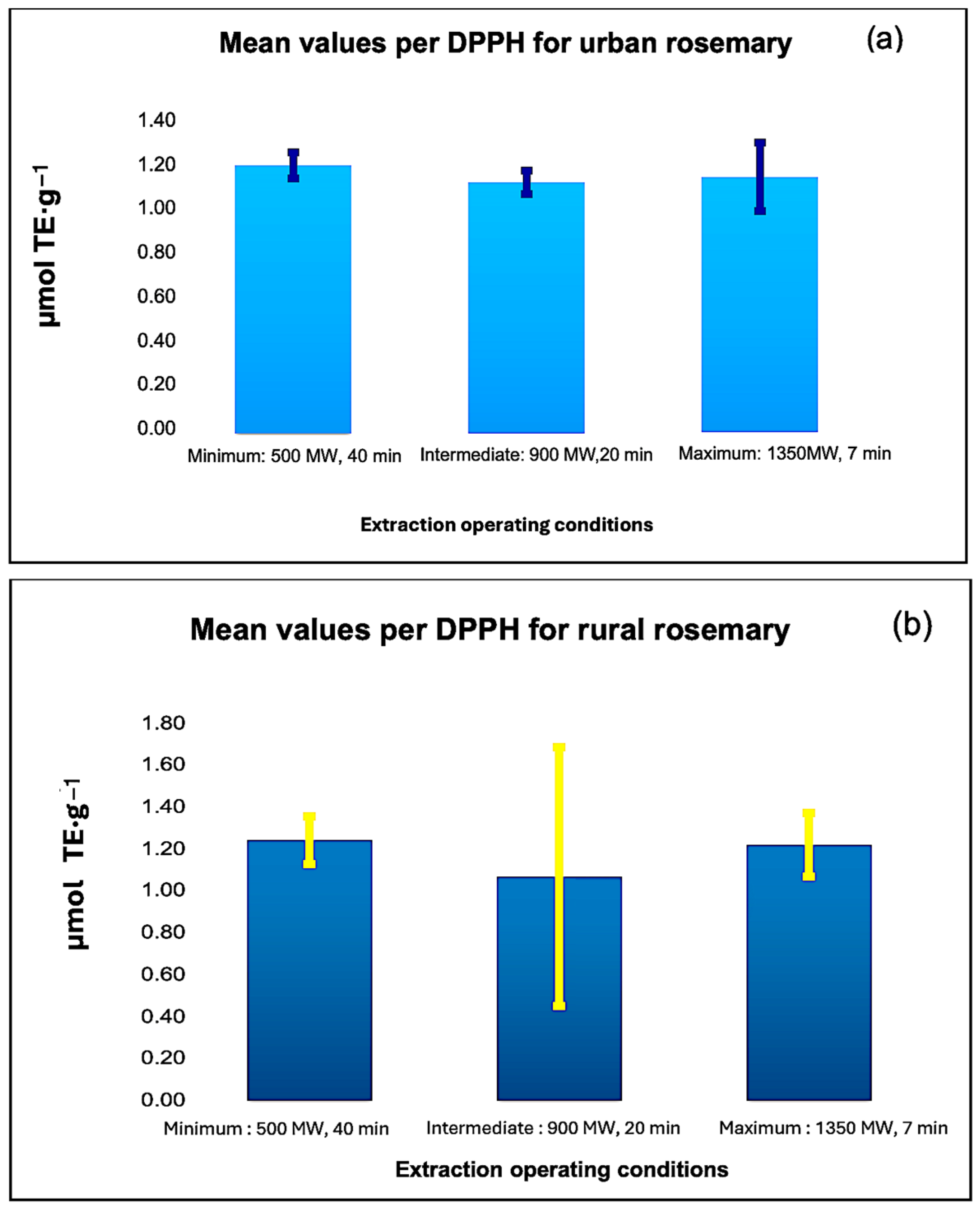

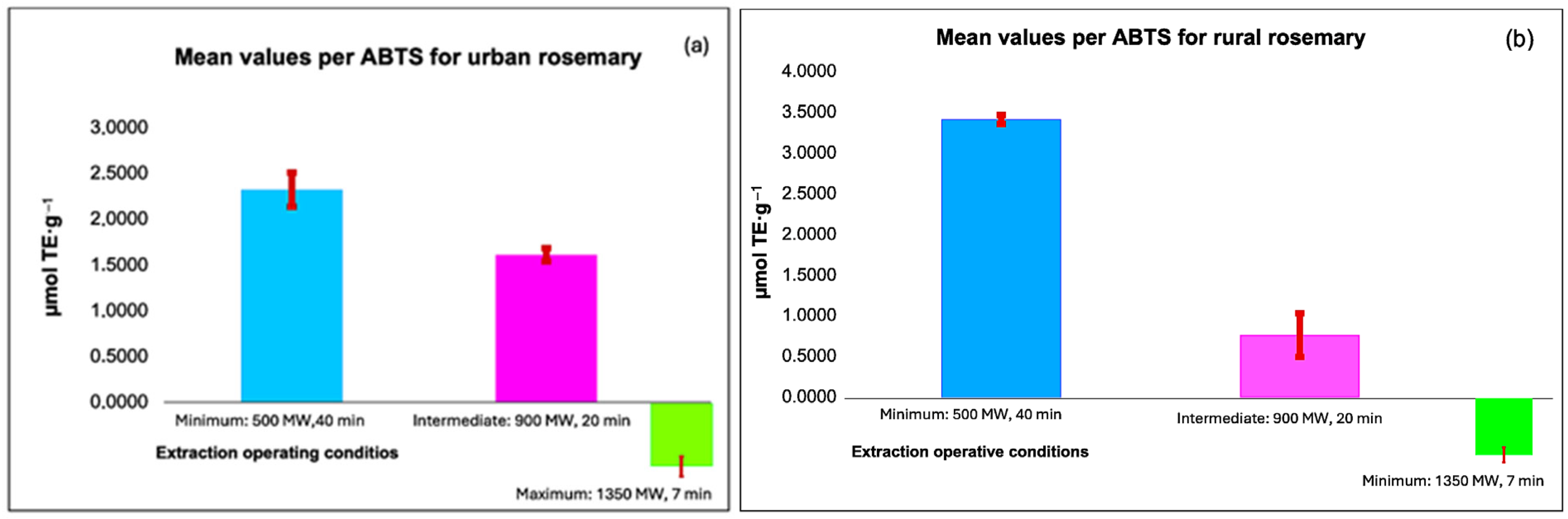

3.2. Antioxidant Capacity

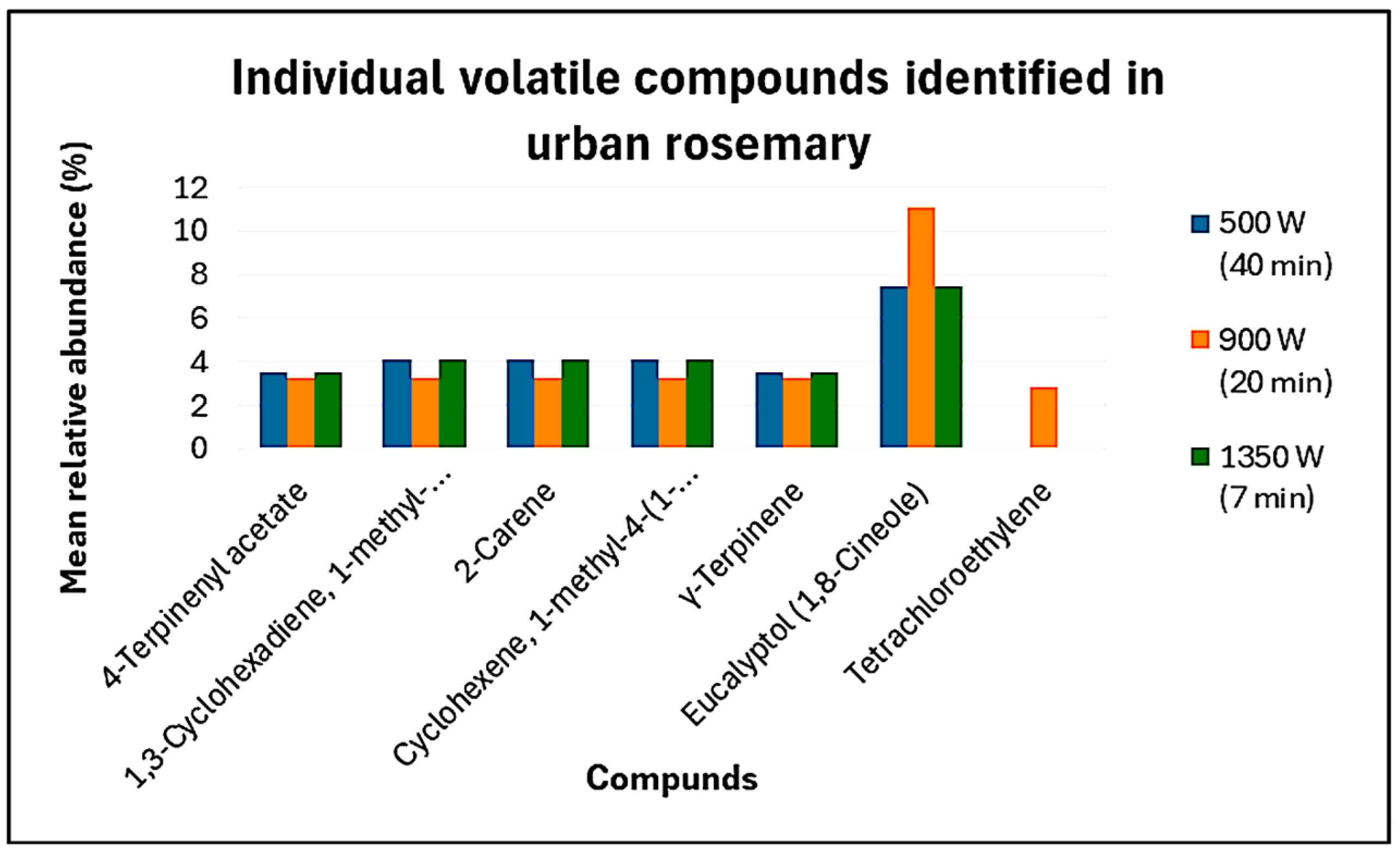

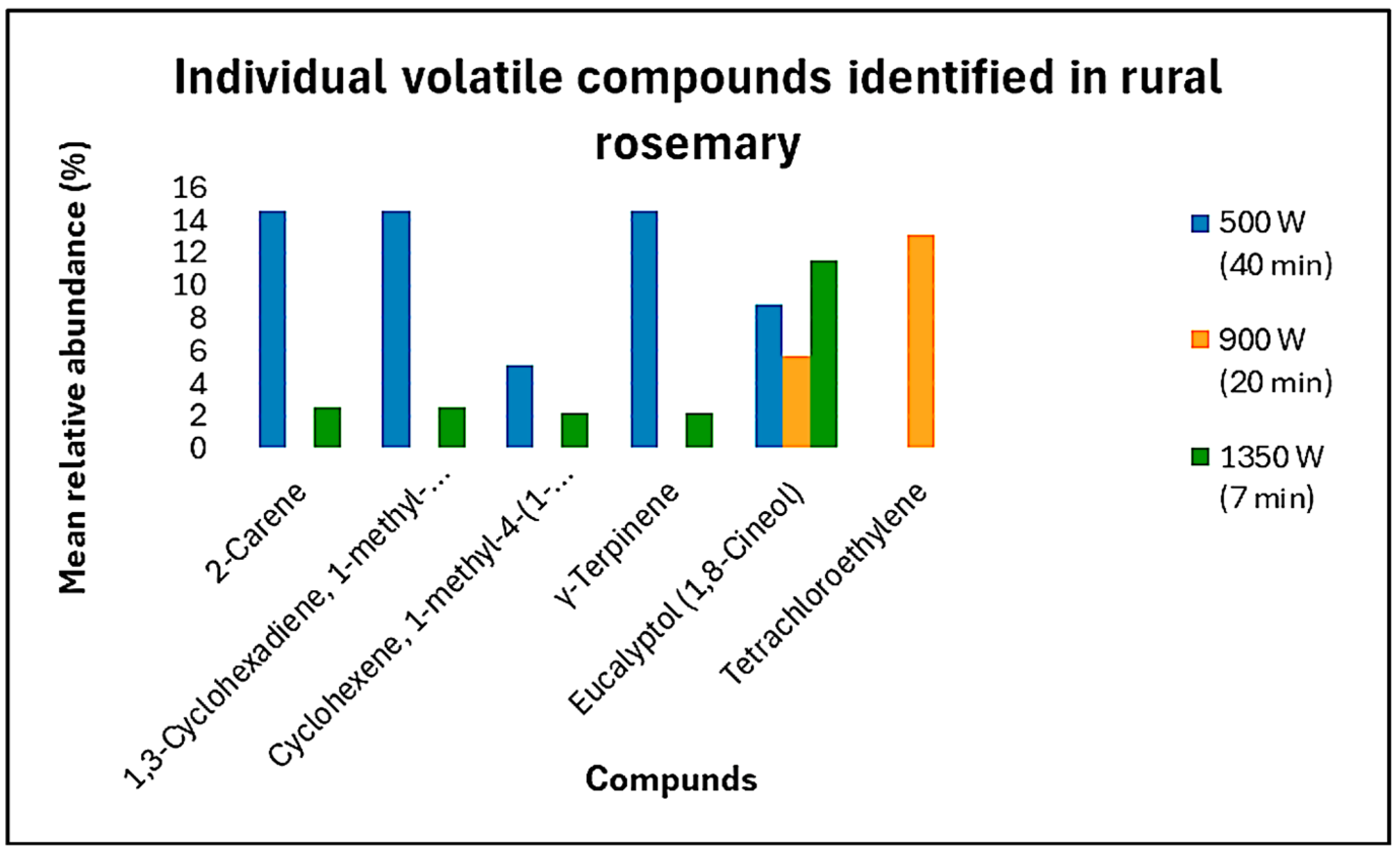

3.3. Volatile Profile Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De la Torre, L.; Navarrete, H.; Muriel, P.; Macía, M.J.; Balslev, H. Enciclopedia de las Plantas Útiles del Ecuador (Con Extracto de Datos), 1st ed.; Herbario QCA de la Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador & Herbario AAU del Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas de la Universidad de Aarhus: Quito, Ecuador, 2008; p. 949. Available online: https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/b80ee8d6-b073-4788-b63e-176042ec952d/content (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Sánchez, M.F.O. Manual Práctico de Aceites Esenciales; Aiyana Ediciones: Avalon Beach, Australia, 2006; p. 247. Available online: https://books.google.com.ec/books?hl=es&lr=&id=cW5TsDKqx9wC&oi=fnd&pg=PA159&dq=S%C3%A1nchez,+M.+F.+O.+ACEITES+ESENCIALES,+AROMAS+Y+PERFUMES,+MANUAL+PRACTICO+DE&ots=LpU2KTiznl&sig=KWCoRsi7xXydYegfYQ-8zFEIzk0&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Camus, J.A.; Trujillo, M.A. Contribucion a la química de los aceites esenciales provenientes del oregano. Rev. Boliv. Química 2011, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, S.V.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Mihai, C.-T.; Gradinaru, A.C.; Mandici, A.; Ciocarlan, N.; Miron, A.; Aprotosoaie, A.C. Chemical profile and bioactivity evaluation of Salvia species from Eastern Europe. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Villa, E.; Sáenz-Galindo, A.; Castañeda-Facio, A.O.; Narro-Céspedes, R.I. Romero (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): Su Origen, Importancia y Generalidades de Sus Metabolitos Secundarios. TIP Rev. Espec. Cienc. Químico-Biológicas 2020, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature India. Timing of Rosemary Harvest Determines Essential Oil Yield. Nat. India 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C. Extracción, caracterización y purificación de aceites esenciales de las hojas de laurel de cera (Morella pubescens) y romero (Rosmarinus officinalis) como alternativa de Desarrollo agroindustrial para el departamento de Nariño. Bachelor Thesis, Universidad de Nariño, San Juan de Pasto, Colombia, 2010. Available online: https://sired.udenar.edu.co/11481/1/81550.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Quinatoa, O. Estudio Comparativo de la Dinámica de Destilación del Aceite Esencial de Pimenta racemosa (mill) j.w. Moore por los Métodos de Hidrodestilación e Hidrodestilación Asistida por Microonda. Bachelor Thesis, Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, G.; Osorio, M.R.; Martínez, S.R. Comparison of two methods for extraction of essential oil from Citrus sinensis L. Rev. Cubana Farm. 2015, 49, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, S.; Fazlali, A.; Hamedi, H. Microwave-assisted hydro-distillation of essential oil from rosemary: Comparison with traditional distillation. Avicenna J. Med. Biotech. 2018, 10, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nateghi, L.; Rashidi, L.; Pourahmad, R.; Nodeh, H.R. Effect of essential oils of chaville (Ferulago contracta), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and lavender (Lavandula officinalis) on the thermal stability of camelina oil under accelerated conditions. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yeasmin, F.; Prasad, P.; Sahu, J.K. Effect of ultrasound on physicochemical, functional and antioxidant properties of red kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) proteins extract. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.N.T.; Tran, H.T.; Pham, D.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Le, T.X. Comparison Of Chemical Composition Of Essential Oil Of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Obtained By Three Extraction Methods: Hydrodistillation, Steam Distillation, And Microwave-Assisted Hydrodistillation. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 1583–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, N. Microwave Heating Induces Oxidative Degradation of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 25, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakar, E.H.; Zeroual, A.; Kasrati, A.; Gharby, S. Combined Effects of Domestication and Extraction Technique on Essential Oil Yield, Chemical Profiling, and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.). J. Food Biochem. 2023, 1, 6308773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.R.; Meléndez, L.A.; Cosío, S.M.R. Procedimientos para la Extracción de Aceites Esenciales en Plantas Aromáticas, 1st ed.; Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste: La Paz, Baja California Sur, México, 2012; Available online: https://cibnor.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1001/540/1/rodriguez_m.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Lax Vivancos, V. Estudio de la Variabilidad Química, Propiedades Antioxidantes y Biocidas de Poblaciones Espontáneas de Rosmarinus officinalis L. en la Región de Murcia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2014. Available online: https://conocimientoabierto.carm.es/jspui/bitstream/20.500.11914/1003/1/Tesis%20Vanesa%20Lax%20.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Dhouibi, I.; Flamini, G.; Bouaziz, M. Comparative Study on the Essential Oils Extracted from Tunisian Rosemary and Myrtle: Chemical Profiles, Quality, and Antimicrobial Activities. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 6431–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshale, F.; Narendiran, K.; Beyan, S.M.; Srinivasan, N.R. Extraction of Essential Oil from Rosemary Leaves: Optimization by Response Surface Methodology and Mathematical Modeling. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, F.M.; Laratta, B. Rosemary Essential Oil Extraction and Residue Valorization by Means of Polyphenols Recovery. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2023, 26, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhani, F.; El Aboudi, A.; Boujraf, A.; Dallahi, Y. Influence of Harvest Time and Environmental Factors on the Yield and Chemical Composition of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Essential Oil in Northeast Morocco. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2024, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhbari, M.; Masoum, S.; Aghababaei, F.; Hamedi, S. Optimization of Microwave Assisted Extraction of Essential Oils from Iranian Rosmarinus officinalis L. Using RSM. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2197–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, J.; Gong, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Chi, F. Rosemary and tea tree essential oils exert antibiofilm activities in vitro against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magtalas, T.J.; Anapi, G.R. Evaluation of Bacteriostatic Effect of Rosemary and Oregano Essential Oils Against a Non-pathogenic Surrogate of Salmonella spp. (E. coli ATCC 9637). Biol Life Sci. Forum 2025, 40, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbardar, M.G.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Therapeutic Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and Its Active Constituents on Nervous System Disorders. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetia, M.P.; Ashraf, G.J.; Sahu, R.; Nandi, G.; Karunakaran, G.; Paul, P.; Dua, T.K. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Essential Oil: A Review of Extraction Technologies, and Biological Activities. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, N.; Loh, M.; Harrison, P. Tetrachloroethylene. In WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; p. 9. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK138706/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Ebrahimzadeh, G.; Omer, A.K.; Naderi, M.; Sharafi, K. Human Health Risk Assessment of Potentially Toxic and Essential Elements in Medicinal Plants Consumed in Zabol, Iran, using the Monte Carlo simulation method. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.M.; Faustino, C.; Garcia, C.; Ladeiras, D.; Reis, C.P.; Rijo, P. Rosmarinus officinalis L.: An Update Review of Its Phytochemistry and Biological Activity. Future Sci. OA 2018, 4, FSO283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Description |

|---|---|

| Part of S. rosmarinus L. | Fresh areal parts visually inspected before sampling (intact and healthy leaves) |

| Area location | Quito city: 0°07′47.6″ S 78°27′60.0″ W Atuntaqui: 0°20′00.6″ N 78°13′35.6″ W |

| Altitude above sea level | Quito city: 2.850 m Atuntaqui: 2.360 m |

| Collection date | Quito: 19 January 2025 Atuntaqui: 23 January 2025 |

| Parameters | Conditions |

|---|---|

| GC-detector | MS |

| Column | Agilent DB-5MS UI de 0.25 mm × 50 m × 0.25 μM |

| Injector temperature, °C | 325 °C |

| Split rate | 10:1 |

| Injection volume, μM | 2 |

| Carrier gas | grade 5.0 Helium 5.0, 99.99% purity |

| Average gas velocity, cm·s−1 | 31.232 |

| Pressure, psi | 19.185 |

| Operative Conditions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Minimum: Potential 500 MW/Time 40 min | Intermediate: Potential 900 MW/Time 20 min | Maximum: Potential 1350 MW/Time 7 min | |||

| Appearance | urban | rural | urban | rural | urban | rural |

| slightly yellow | cloudy | slightly yellow | cloudy | slightly yellow | cloudy | |

| Odor | moderate | intense | moderate | intense | moderate | intense |

| Density (g·mL−1) | 0.7370 | 0.8850 | 0.8880 | 0.9110 | 1.0270 | 1.0080 |

| Refractive index | 1.4720 | 1.4710 | 1.4695 | 1.4695 | 1.4690 | 1.4700 |

| Solubility in ethanol (%v/v) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fukalova Fukalova, T.; Calderón Jácome, A.C.; Alcívar León, C.D.; Garofalo García, M.G.; Villacres, E. Comparison Between the Volatile Compounds of Essential Oils Isolated from Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus L.) and Its Antioxidant Capacity from Ecuadorian Highlands. Chem. Proc. 2025, 18, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26742

Fukalova Fukalova T, Calderón Jácome AC, Alcívar León CD, Garofalo García MG, Villacres E. Comparison Between the Volatile Compounds of Essential Oils Isolated from Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus L.) and Its Antioxidant Capacity from Ecuadorian Highlands. Chemistry Proceedings. 2025; 18(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26742

Chicago/Turabian StyleFukalova Fukalova, Tamara, Ana Cristina Calderón Jácome, Christian David Alcívar León, Marcos Geovany Garofalo García, and Elena Villacres. 2025. "Comparison Between the Volatile Compounds of Essential Oils Isolated from Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus L.) and Its Antioxidant Capacity from Ecuadorian Highlands" Chemistry Proceedings 18, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26742

APA StyleFukalova Fukalova, T., Calderón Jácome, A. C., Alcívar León, C. D., Garofalo García, M. G., & Villacres, E. (2025). Comparison Between the Volatile Compounds of Essential Oils Isolated from Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus L.) and Its Antioxidant Capacity from Ecuadorian Highlands. Chemistry Proceedings, 18(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-29-26742