Psychometric Properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents (HFS-P) in the Portuguese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Data

2.2.2. Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents

2.2.3. Diabetes Distress

2.2.4. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Ethics and Data Collection

2.3.2. Translation Process of HFS-P

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Normality Assessments

2.4.2. Factorial Validity and Fit Indices

2.4.3. Reliability Analysis

2.4.4. Convergent Validity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Descriptive Data Analysis

3.3. Twenty-Six-Item HFS-P—CFA and Reliability

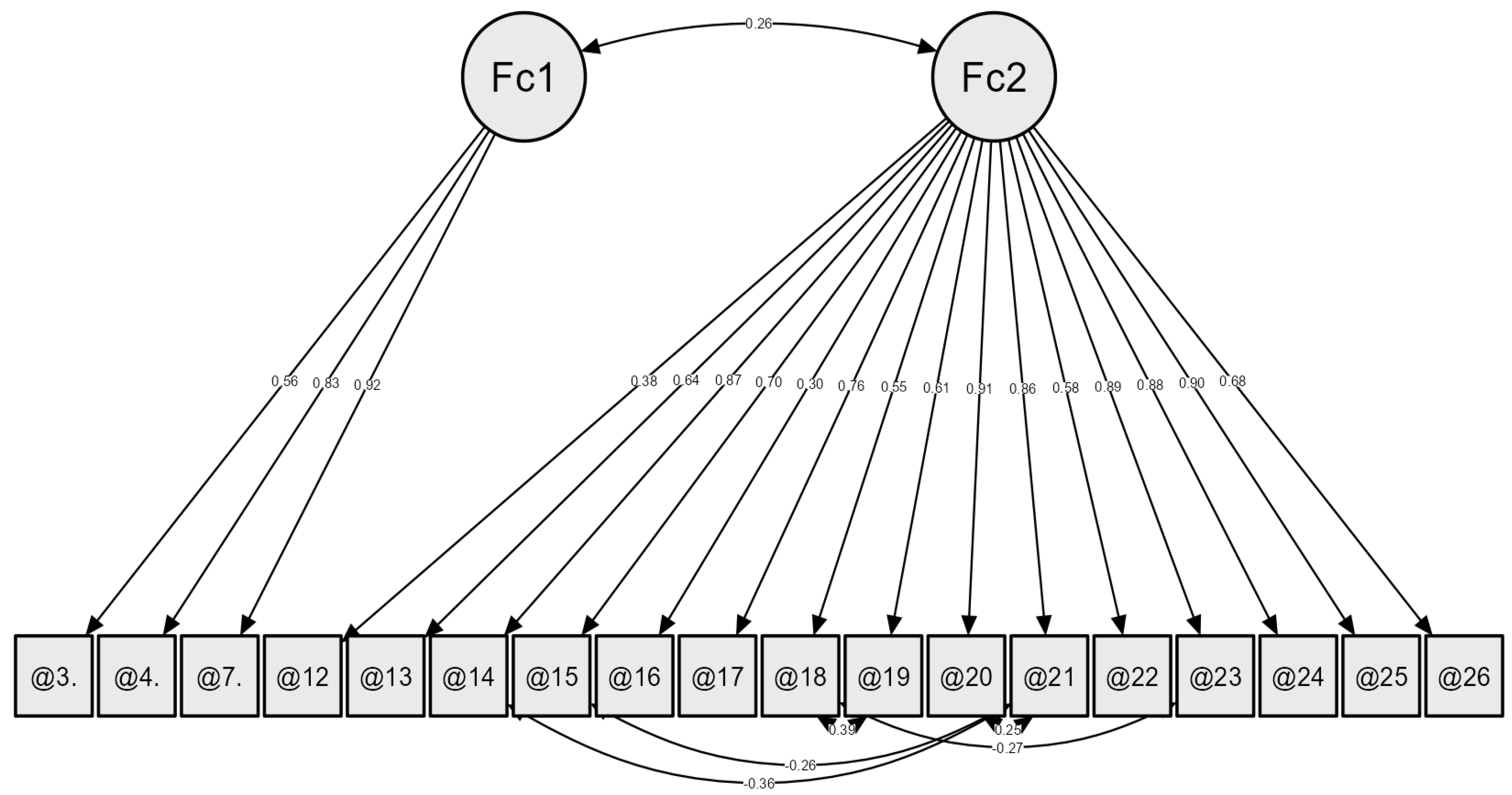

3.4. Eighteen-Item HFS-P—CFA and Reliability

3.5. Convergent Validity Assessment

4. Discussion

Limitations, Future Research, Strengths, and Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T1D | Type 1 Diabetes |

| FH | Fear of Hypoglycemia |

| HFS-P | Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents |

| HFS | Hypoglycemia Fear Survey |

| REDCHIP | Reducing Emotional Distress For Childhood Hypoglycemia in Parents |

| PAID-PR | Problem Areas in Diabetes Survey—Parent Revised |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety Stress Scales |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SRMSR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| χ2/DF | Chi-Square Divided by Degrees of Freedom |

| RMSEA | Root Men Square Error of Approximation |

| M | Mean |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error of Skewness |

| K | Kurtosis |

| SK | Standard Error of Kurtosis |

| SW | Shapiro–Wilk |

| HFS-P-NF | Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parent, Nighttime Fear |

| HFS-P-YC | Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents of Young Children |

| HFS-C | Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Child Version |

Appendix A. HFS-P Versions Overview

| Country | Authors and Year | HFS-P Structure, Items, and Final Version |

|---|---|---|

| Greece | Kostopoulou et al. [33] |

|

| Italy | Tumini et al. [34] |

|

| Norway | Haugstvedt et al. [32] |

|

| Portugal | Costa et al. [36] |

|

| United States (original study) | Clarke et al. [28] |

|

| United States | O’Donnell et al. [24] |

|

| United States | Shepard et al. [31] |

|

References

- Gonder-Frederick, L. Fear of hypoglycemia: A review. Diabet. Hypoglycemia 2013, 5, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bombaci, B.; Torre, A.; Longo, A.; Pecoraro, M.; Papa, M.; Sorrenti, L.; La Rocca, M.; Lombardo, F.; Salzano, G. Psychological and Clinical Challenges in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes during Adolescence: A Narrative Review. Children 2024, 11, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchini, S.; Tumini, S.; Scaramuzza, A.E.; Bonfanti, R.; Delvecchio, M.; Franceschi, R.; Iafusco, D.; Lenzi, L.; Mozzillo, E.; Passanisi, S.; et al. Recommendations for recognizing, risk stratifying, treating, and managing children and adolescents with hypoglycemia. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1387537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desouza, C.V.; Bolli, G.B.; Fonseca, V. Hypoglycemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular events. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.; Mukherjee, J.J.; Venkataraman, S.; Bantwal, G.; Shaikh, S.; Saboo, B.; Das, A.K.; Ramachandran, A. Hypoglycemia: The neglected complication. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzen, L.; Schultes, B.; Meyhöfer, S.M.; Meyhöfer, S. Hypoglycemia unawareness—A review on pathophysiology and clinical implications. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munugoti, S.; Reddy, G.; Singh, R.; Kakarlapudi, M.; Muralidhara, S.; Rosenfeld, C. Diabetes-related hypoglycemia, contributing risk factors, glucagon prescriptions in two community hospitals. Endocr. Metab. Sci. 2024, 15, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.B.; Karges, B.; Dovc, K.; Naranjo, D.; Arbelaez, A.M.; Mbogo, J.; Javelikar, G.; Jones, T.W.; Mahmud, F.H. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2022: Assessment and management of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1322–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatle, H.; Skrivarhaug, T.; Bjørgaas, M.R.; Åsvold, B.O.; Rø, T.B. Prevalence and associations of impaired awareness of hypoglycemia in a pediatric type 1 diabetes population—The Norwegian Childhood Diabetes Registry. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 209, 111093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Shin, H. The burdens faced by parents of preschoolers with type 1 diabetes mellitus: An integrative review. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2023, 29, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Name, M.A.; Hilliard, M.E.; Boyle, C.T.; Miller, K.M.; DeSalvo, D.J.; Anderson, B.J.; Laffel, L.M.; Woerner, S.E.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Tamborlane, W.V. Nighttime is the worst time: Parental fear of hypoglycemia in young children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 6. Glycemic goals and hypoglycemia: Standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S111–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battelino, T.; Danne, T.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Amiel, S.A.; Beck, R.; Biester, T.; Bosi, E.; Buckingham, B.A.; Cefalu, W.T.; Close, K.L.; et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: Recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Piscopo, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Chianese, A.; Cascella, C.; Affuso, G.; Borriello, A.; Curto, S.; Rollato, A.S.; Testa, V.; et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in parents of children with type 1 diabetes trained for intranasal glucagon use. J. Psychosom. Res. 2024, 184, 111856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Liu, L.; Bi, Y.; Li, X.; Kan, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, S.; Zou, Y.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Related factors associated with fear of hypoglycemia in parents of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes—A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 66, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassi, G.; Mancinelli, E.; Di Riso, D.; Salcuni, S. Parental stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms associated with self-efficacy in pediatric type 1 diabetes: A literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, K.A.; Raymond, J.; Naranjo, D.; Patton, S.R. Fear of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents and their parents with type 1 diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2016, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbeeten, K.C.; Perez Trejo, M.E.; Tang, K.; Chan, J.; Courtney, J.M.; Bradley, B.J.; McAssey, K.; Clarson, C.; Kirsch, S.; Curtis, J.R.; et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes and their parents: Effect of pump therapy and continuous glucose monitoring with option of low glucose suspend in the CGM TIME trial. Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 22, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.; Pereira, B.; Patton, S.R.; Brandão, T. Parental psychosocial variables and glycemic control in T1D pediatric age: A systematic review. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2024, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.P.; McDarby, V.; Cody, D. Fear of hypoglycemia in parents of children with type 1 diabetes. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2014, 50, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzon, A.D.; Majidi, S.; Clements, M.A.; Patton, S.R. The relationship between parent fear of hypoglycemia and youth glycemic control across the recent-onset period in families of youth with type 1 diabetes. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, S.R. Hypoglycaemic-related fear in parents of children with poor glycaemic control of their type 1 diabetes is associated with poorer glycaemic control in their child and parental emotional distress. Evid. Based Nurs. 2011, 14, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 14. Children and adolescents: Standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S258–S281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, S.; Weissberg-Benchell, J.; Barnard, K.; Jaser, S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Hood, K.K. Psychometric properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey in a clinical sample of adolescents with Type 1 diabetes and their caregivers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, S.R.; Clements, M.A.; Marker, A.M.; Nelson, E.L. Intervention to reduce hypoglycemia fear in parents of young kids using video-based telehealth (REDCHIP). Pediatr. Diabetes 2020, 21, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.J.; Irvine, A.; Gonder-Frederick, L.; Nowacek, G.; Butterfield, J. Fear of hypoglycemia: Quantification, validation, and utilization. Diabetes Care 1987, 10, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonder-Frederick, L.A.; Schmidt, K.M.; Vajda, K.A.; Greear, M.L.; Singh, H.; Shepard, J.A.; Cox, D.J. Psychometric properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey-II for adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, W.L.; Gonder-Frederick, L.A.; Snyder, A.L.; Cox, D.J. Maternal fear of hypoglycemia in their children with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 11, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monzon, A.D.; Cushing, C.C.; McDonough, R.; Clements, M.; Gonder-Frederick, L.; Patton, S.R. The development and initial validation of items to assess parent fear of nighttime hypoglycemia. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, S.R.; Dolan, L.M.; Henry, R.; Powers, S.W. Parental fear of hypoglycemia: Young children treated with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Pediatr. Diabetes 2007, 8, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, J.A.; Vajda, K.; Nyer, M.; Clarke, W.; Gonder-Frederick, L. Understanding the construct of fear of hypoglycemia in pediatric type 1 diabetes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugstvedt, A.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Aarflot, M.; Rokne, B.; Graue, M. Assessing fear of hypoglycemia in a population-based study among parents of children with type 1 diabetes: Psychometric properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey–Parent version. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2015, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostopoulou, E.; Andreopoulou, O.; Daskalaki, S.; Kotanidou, E.; Vakka, A.; Galli-Tsinopoulou, A.; Spiliotis, B.E.; Gonder-Frederick, L.; Fouzas, S. Translation and validation study of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey in a Greek population of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus and their parents. Children 2023, 10, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumini, S.; Fioretti, E.; Rossi, I.; Cipriano, P.; Franchini, S.; Guidone, P.I.; Petrosino, M.I.; Saggino, A.; Tommasi, M.; Picconi, L.; et al. Fear of hypoglycemia in children with type 1 diabetes and their parents: Validation of the Italian version of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey for Children and for Parents. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, J.T.; Volkening, L.K.; Butler, D.A.; Antisdel-Lomaglio, J.; Anderson, B.J.; Laffel, L.M.B. Re-examining a measure of diabetes-related burden in parents of young people with Type 1 diabetes: The Problem Areas in Diabetes Survey–Parent Revised version (PAID-PR). Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.; Brandão, T. Preliminary Validation of Type 1 Diabetes Scales: Distress and Fear of Hypoglycemia in Parents of Children and Adolescents. In Proceedings of the XIII Ibero-American Congress of Psychology/6th Congress of the Portuguese Psychologists’ Association, Lisbon, Portugal, 25–27 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Honrado, A.A.J.D.; Leal, I. Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade, depressão e stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2004, 5, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambleton, R.K.; Merenda, P.F.; Spielberger, C.D. (Eds.) Adapting Educational and Psychological Tests for Cross-Cultural Assessment; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonder-Frederick, L.A.; Vajda, K.A.; Schmidt, K.M.; Cox, D.J.; Devries, J.H.; Erol, O.; Kanc, K.; Schächinger, H.; Snoek, F.J. Examining the behaviour subscale of the Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey: An international study. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abitbol, L.; Palmert, M.R. When low blood sugars cause high anxiety: Fear of hypoglycemia among parents of youth with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Can. J. Diabetes 2021, 45, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pate, T.; Klemenčič, S.; Battelino, T.; Bratina, N. Fear of hypoglycemia, anxiety, and subjective well-being in parents of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattell, R.B. The Scientific Use of Factor Analysis; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Parents | Children |

|---|---|---|

| T1D Duration | M = 5.92; SD = 3.52 | |

| T1D Treatment | Insulin Pump (68.6%) and Insulin Pens (31.4%) | |

| Districts | Lisbon (20.6%), Porto (19.6%), Braga (8.8%), Setúbal (7.8%), Aveiro (5.9%), and Coimbra (4.9%) | Lisbon (20.6%), Porto (19.6%), Braga (8.8%), Setúbal (7.8%), Aveiro (5.9%), and Coimbra (4.9%) |

| Type of Residence Area | Urban area (77.5%) and Rural area (20.6%) | Urban area (77.5%) and Rural area (20.6%) |

| Sex | Female (92.2%) and Male (7.8%) | Female (48%) and Male (52%) |

| Age | M = 44.58 years old SD = 5.01 | M = 12.67 years old; SD = 2.58 |

| Professional status | Employed (85.5%), | |

| Marital Status | Married/in a civil union (81.4%) | |

| Fear of Hypoglycemia | M = 45.70; SD = 15.83 (Total score) M = 1.76; SD = 0.60 (Item score) |

| Items | M | SE | SD | Sk | SE | K | SE | SW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.96 | 0.11 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.24 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.79 * |

| 2 | 3.17 | 0.11 | 1.11 | −1.14 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.47 | 0.75 * |

| 3 | 1.32 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.86 * |

| 4 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.83 * |

| 5 | 2.32 | 0.12 | 1.19 | −0.08 | 0.24 | −1.02 | 0.47 | 0.90 * |

| 6 | 2.67 | 0.13 | 1.30 | −0.60 | 0.24 | −0.79 | 0.47 | 0.85 * |

| 7 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.24 | −0.05 | 0.47 | 0.85 * |

| 8 | 3.91 | 0.03 | 0.32 | −3.85 | 0.24 | 15.64 | 0.47 | 0.30 * |

| 9 | 2.35 | 0.12 | 1.16 | −0.18 | 0.24 | −0.63 | 0.47 | 0.90 * |

| 10 | 3.07 | 0.10 | 1.01 | −0.79 | 0.24 | −0.26 | 0.47 | 0.82 * |

| 11 | 2.88 | 0.11 | 1.14 | −0.75 | 0.24 | −0.24 | 0.47 | 0.84 * |

| 12 | 1.92 | 0.11 | 1.12 | 0.33 | 0.24 | −0.60 | 0.47 | 0.90 * |

| 13 | 1.35 | 0.12 | 1.21 | 0.63 | 0.24 | −0.48 | 0.47 | 0.87 * |

| 14 | 1.12 | 0.14 | 1.41 | 0.94 | 0.24 | −0.52 | 0.47 | 0.76 * |

| 15 | 2.22 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.24 | −0.56 | 0.47 | 0.87 * |

| 16 | 0.80 | 0.10 | 0.96 | 1.15 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.47 | 0.78 * |

| 17 | 1.86 | 0.12 | 1.21 | 0.30 | 0.24 | −0.71 | 0.47 | 0.90 * |

| 18 | 1.13 | 0.10 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.24 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.85 * |

| 19 | 1.23 | 0.12 | 1.17 | 0.76 | 0.24 | −0.16 | 0.47 | 0.86 * |

| 20 | 1.40 | 0.14 | 1.38 | 0.76 | 0.24 | −0.69 | 0.47 | 0.83 * |

| 21 | 1.23 | 0.13 | 1.29 | 0.93 | 0.24 | −0.20 | 0.47 | 0.82 * |

| 22 | 0.92 | 0.12 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.76 * |

| 23 | 0.88 | 0.13 | 1.35 | 1.37 | 0.24 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.68 * |

| 24 | 1.35 | 0.15 | 1.52 | 0.69 | 0.24 | −1.02 | 0.47 | 0.79 * |

| 25 | 1.31 | 0.13 | 1.33 | 0.90 | 0.24 | −0.29 | 0.47 | 0.82 * |

| 26 | 2.33 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.43 | 0.24 | −0.03 | 0.47 | 0.84 * |

| Variables | 1. HFS-P Total | 2. HFS-P Behavior | 3. HFS-P Worry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HFS-P Total | — | 0.46 *** | 0.98 *** |

| 2. HFS-P Behavior | 0.46 *** | — | 0.28 ** |

| 3. HFS-P Worry | 0.98 *** | 0.28 ** | — |

| 4. Depression (DASS-21) | 0.29 ** | 0.20 * | 0.27 ** |

| 5. Anxiety (DASS-21) | 0.32 *** | 0.11 | 0.32 *** |

| 6. Stress (DASS-21) | −0.01 | −0.92 | −0.01 |

| 7. PAID-PR Total | 0.23 * | 0.14 | 0.24 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, V.; Patton, S.R.; do Vale, S.; Sampaio, L.; Limbert, C.; Brandão, T. Psychometric Properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents (HFS-P) in the Portuguese Context. Diabetology 2025, 6, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6080071

Costa V, Patton SR, do Vale S, Sampaio L, Limbert C, Brandão T. Psychometric Properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents (HFS-P) in the Portuguese Context. Diabetology. 2025; 6(8):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6080071

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Vasco, Susana R. Patton, Sónia do Vale, Lurdes Sampaio, Catarina Limbert, and Tânia Brandão. 2025. "Psychometric Properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents (HFS-P) in the Portuguese Context" Diabetology 6, no. 8: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6080071

APA StyleCosta, V., Patton, S. R., do Vale, S., Sampaio, L., Limbert, C., & Brandão, T. (2025). Psychometric Properties of the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey—Parents (HFS-P) in the Portuguese Context. Diabetology, 6(8), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6080071