Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Eight-Year Follow-Up Study in Southern Israel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

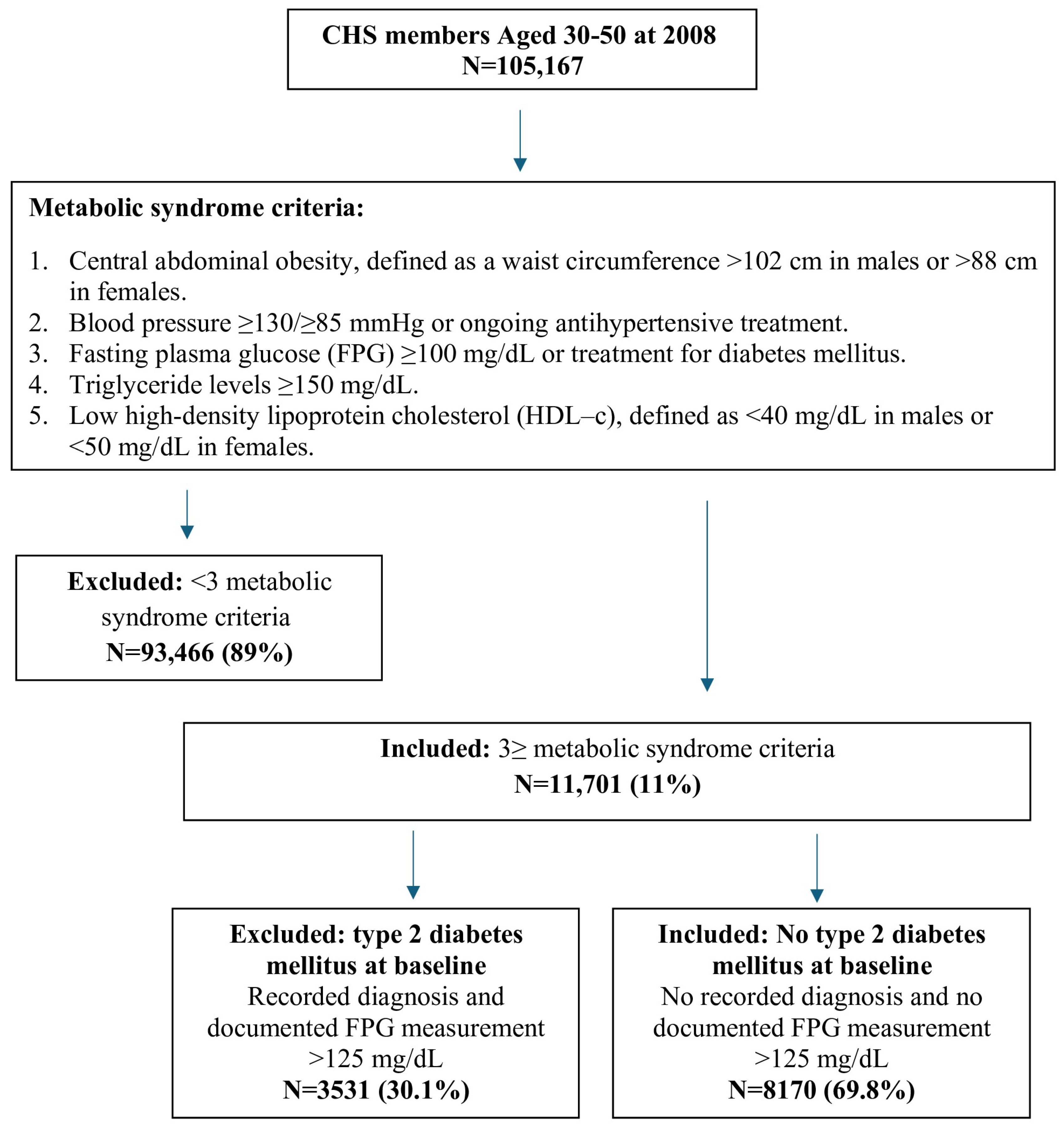

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Definition of Metabolic Syndrome

- Central abdominal obesity, defined as a waist circumference > 102 cm in males or >88 cm in females.

- Blood pressure ≥130/≥85 mmHg or ongoing antihypertensive treatment.

- Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 100 mg/dL or treatment for diabetes mellitus.

- Triglyceride levels ≥ 150 mg/dL.

- Low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), defined as <40 mg/dL in males or <50 mg/dL in females.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Outcome Measures

2.8. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Changes in MetS Indices over Eight Years

3.2. Healthcare Utilization

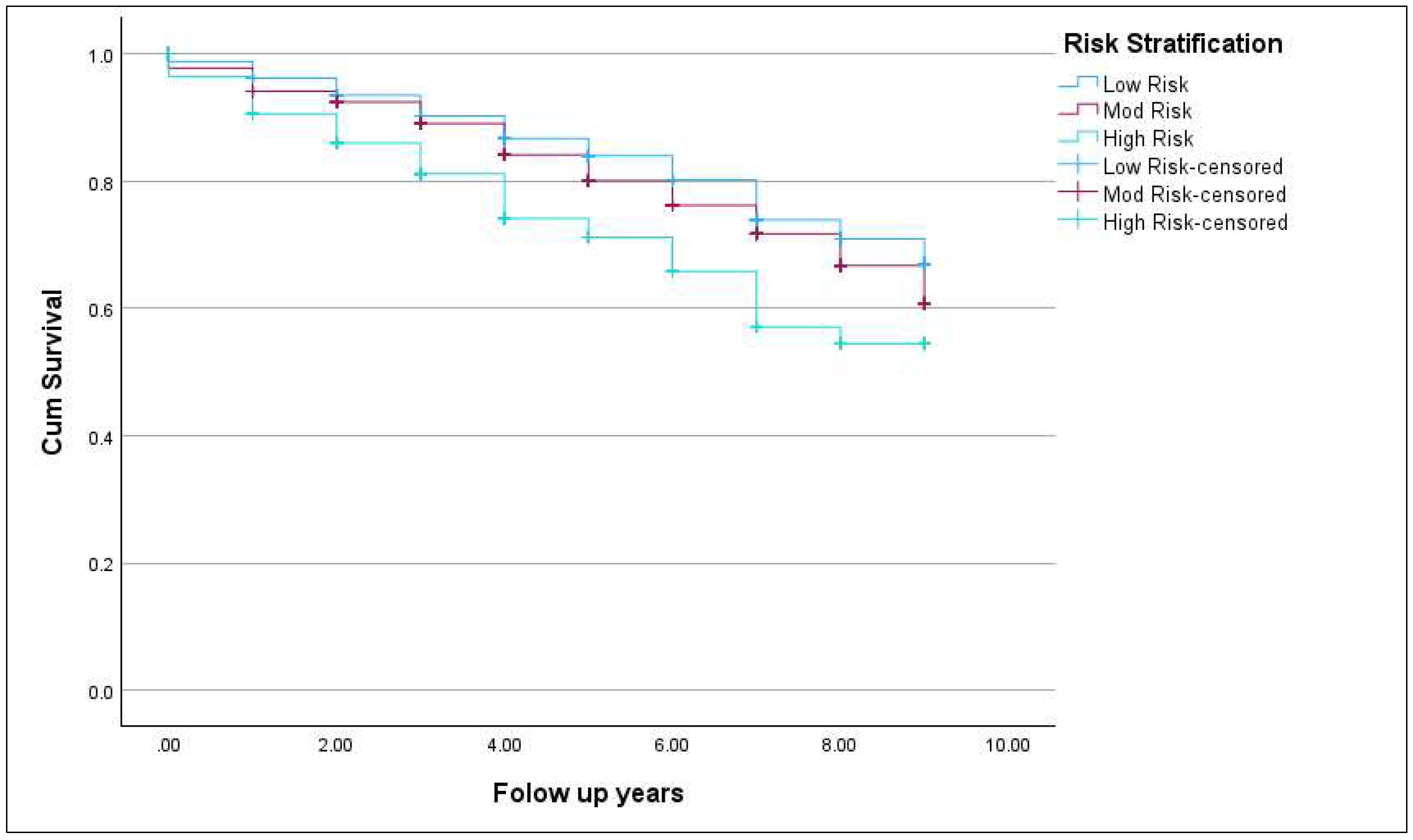

3.3. Incidence of New-Onset T2DM

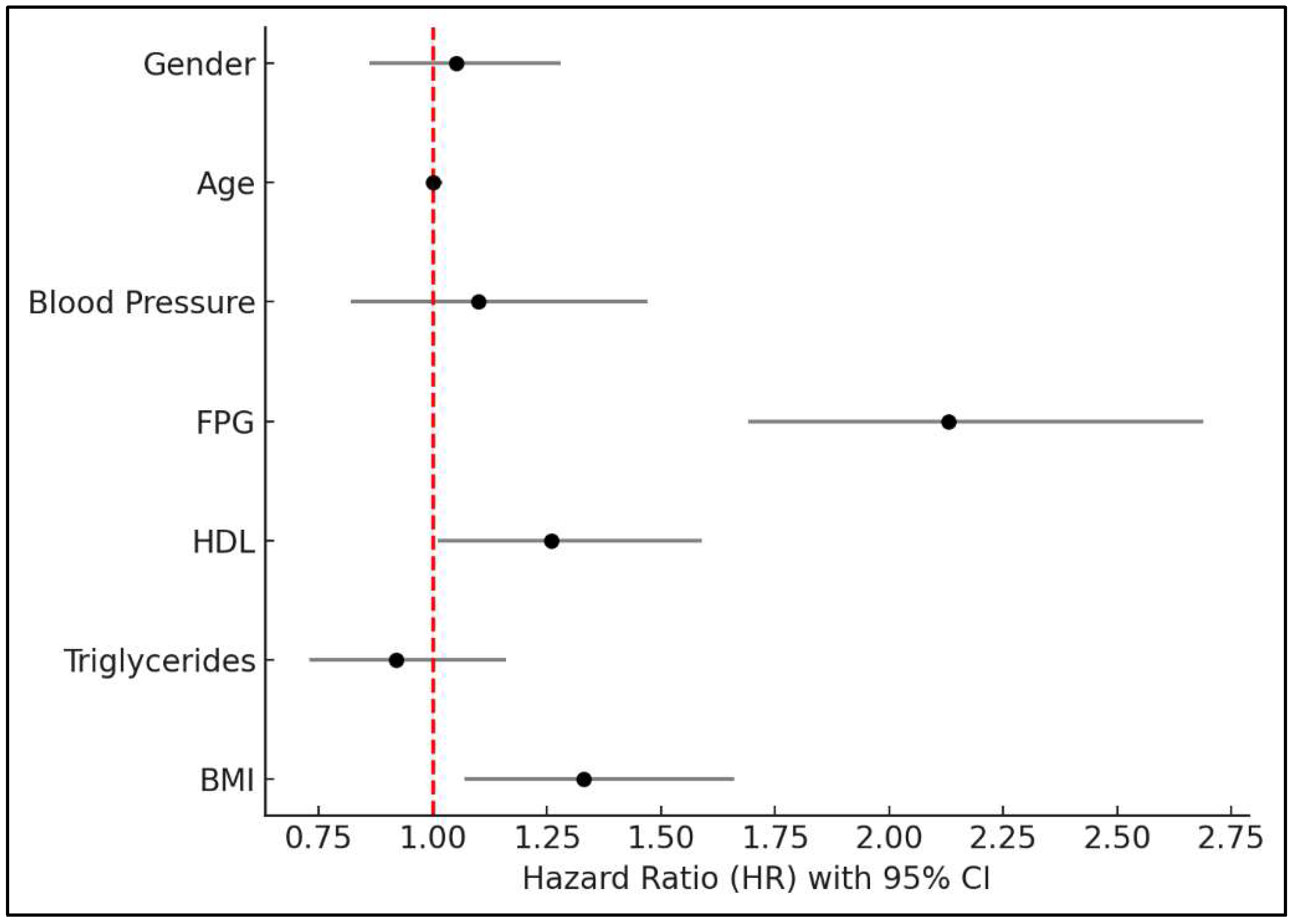

3.4. Risk Factors for New-Onset T2DM

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MetS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| FPG | Fasting plasma glucose |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| CHS | Clalit Health Services |

| IFG | Impaired fasting glucose |

| RR | Relative risk |

| cMetS-S | Continuous MetS severity scores |

| ATP | Adult Treatment Panel |

| HDL-c | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| EMR | Electronic medical records |

| LDL-c | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| PCP | Primary care physician |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| GP | General practitioner |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like Peptide-1 |

| HMO | Health maintenance organization |

Appendix A

| Criteria | Group | N ** | No. of Tests Median (Q1–Q3) (2008–2015) | Beginning of Study Median (Q1–Q3) | End of Study Median (Q1–Q3) | Change Median (Q1–Q3) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | All Study Population | 8045 | 7.0 (4.0, 11.0) | 31.6 (28.4, 35.3) | 31.6 (28.2, 35.4) | 0.15 (−1.21, 1.88) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4321 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 32.8 (29.6, 36.5) | 32.9 (29.1, 36.7) | 0.35 (−1.39, 2.11) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3724 | 6.0 (3.0, 10.0) | 30.5 (27.5, 33.7) | 30.5 (27.4, 33.8) | 0.0 (−1.05, 1.63) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5617 | 6.0 (4.0, 10.0) | 30.8 (27.5, 34.2) | 30.9 (27.5, 34.6) | 0.33 (−9.59, 1.95) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2032 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 33.2 (30.5, 36.9) | 33.0 (29.7, 36.8) | 0.0 (−1.68, 1.73) | 0.771 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 396 | 10.0 (7.0, 16.0) | 35.1 (32.3, 38.3) | 34.3 (30.7, 37.4) | −0.38 (−3.08, 1.28) | <0.001 | |

| Triglycerides | All Study Population | 8163 | 9.0 (6.0, 12.0) | 184.0 (144.0, 240.0) | 165.0 (122.0, 223.0) | −13.0 (−64.0, 31) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4366 | 9.0 (6.0, 12.0) | 169.0 (81.0, 217.0) | 155.0 (114.0, 206.0) | −7.0 (−54.0, 33.25) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3797 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 203.0 (161.0, 264.0) | 179.0 (132.0, 243.0) | −22.0 (−74.0, 26.0) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5717 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 176.0 (131.0, 231.0) | 160.0 (117.0, 215.0) | −10.0 (−61.0, 32.0) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2047 | 9.0 (7.0, 16.0) | 197.0 (161.0, 254.0) | 177.0 (135.0, 238.0) | −17.0 (−70.0, 30.0) | <0.001 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 10.0 (7.0, 14.0) | 201.0 (171.0, 259.0) | 177.0 (137.0, 233.0) | −30.0 (−74.0, 12.0) | <0.001 | |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose | All Study Population | 8146 | 10.0 (6.0, 15.0) | 92.0 (81.0, 103.0) | 101.0 (92.0, 116.0) | 13.0 (0, 26.0) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4361 | 11.0 (7.0, 16.0) | 91.0 (81.0, 102.5) | 101.0 (92.0, 115.0) | 13.0 (0.0, 27.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3785 | 9.0 (6.0, 14.0) | 93.0 (82.0, 104.0) | 102.0 (93.0, 117.0) | 13.0 (1.0, 25.0) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5707 | 10.0 (6.0, 14.0) | 89.0 (80.0, 101.0) | 100.0 (92.0, 112.0) | 13.0 (1.0, 25.0) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2040 | 11.0 (7.0, 16.0) | 96.0 (84.0, 107.0) | 104.0 (94.0, 122.0) | 13.0 (0.0, 28.0) | <0.001 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 13.0 (8.0, 18.0) | 106.0 (101.0, 114.0) | 111.0 (99.0, 138.0) | 9.0 (−6.0, 30.0) | <0.001 | |

| HDL-c | All Study Population | 8164 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 40.0 (35.0, 46.0) | 41.0 (36.0, 48.0) | 1.0 (−3.0, 6.0) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4361 | 9.0 (6.0, 12.0) | 44.0 (39.0, 49.0) | 45.0 (39.0, 51.0) | 1.0 (−4.0, 6.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3794 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 37.0 (33.0, 40.0) | 38.0 (33.0, 43.0) | 1.0 (−3.0, 5.0) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5710 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 41.0 (36.0, 47.0) | 42.0 (36.0, 49.0) | 1.0 (−4.0, 5.0) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2046 | 9.0 (6.0, 13.0) | 39.0 (34.0, 44.2) | 41.0 (35.2, 47.0) | 1.0 (−2.0, 6.0) | <0.001 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 10.0 (7.0, 14.0) | 37.0 (34.0, 42.0) | 39.0 (35.0, 45.0) | 1.0 (−2.0, 6.0) | <0.001 | |

| Systolic blood pressure | All Study Population | 8131 | 11.0 (6.0, 18.0) | 126.0 (119.0, 136.0) | 126.0 (120.0, 134.0) | 0.0 (−11.0, 10) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4358 | 12.0 (7.0, 20.0) | 125.0 (115.0, 135.0) | 125.0 (118.0, 132.0) | 0.0 (−10.0, 10.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3774 | 9.0 (5.0, 15.0) | 130.0 (120.0, 139.0) | 127.0 (120.0, 135.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 9.0) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5690 | 10.0 (6.0, 16.0) | 125.0 (117.0, 135.0) | 125.0 (119.0, 133.0) | 0.0 (−10.0, 10.0) | 0.142 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2044 | 13.0 (7.0, 21.0) | 130.0 (120.0, 140.0) | 127.0 (120.0, 135.0) | −1.0 (−13.0, 10.0) | <0.001 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 397 | 15.0 (10.0, 24.0) | 130.0 (120.0, 140.0) | 129.0 (120.0, 135.0) | −3.0 (−15.0, 9.0) | <0.001 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure | All Study Population | 8132 | 11.0 (6.0, 18.0) | 80.0 (72.0, 85.0) | 78.0 (70.0, 83.0) | −1.0 (−10.0, 5.0) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4357 | 12.0 (7.0, 20.0) | 80.0 (70.0, 84.0) | 77.0 (70.0, 82.0) | −1.0 (−10.0, 6.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3774 | 9.0 (5.0, 15.0) | 80.0 (74.0, 86.0) | 79.0 (72.0, 84.0) | −1.0 (−10.0, 5.0) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5690 | 10.0 (6.0, 16.0) | 80.0 (70.0, 85.0) | 78.0 (70.0, 83.0) | 0.0 (−9.0, 5.0) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2044 | 13.0 (7.0, 21.0) | 80.0 (74.0, 87.0) | 78.0 (71.0, 83.0) | −2.0 (−10.0, 5.0) | <0.001 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 397 | 15.0 (10.0, 24.0) | 80.0 (75.0, 86.5) | 80.0 (74.0, 83.5) | −3.0 (−10.0, 4.0) | <0.001 | |

| LDL | All Study Population | 8066 | 8.0 (5.0, 11.0) | 118.0 (96.0, 141.0) | 109.0 (87.0, 133.0) | −3.55 (−28.0, 13.0) | <0.001 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4346 | 8.0 (5.0, 11.0) | 117.0 (96.0, 139.4) | 111.0 (90.0, 133.0) | −2.0 (−25.0, 15.0) | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3720 | 7.0 (4.0, 10.0) | 120.0 (96.0, 143.0) | 107.0 (85.0, 133.0) | −6.0 (−31.0, 11.0) | <0.001 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5655 | 7.0 (4.0, 11.0) | 118.0 (96.0, 141.0) | 110.0 (89.0, 133.0) | −3.0 (−26.0, 14.0) | <0.001 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2018 | 8.0 (5.0, 11.0) | 118.0 (96.0, 142.0) | 107.0 (84.0, 132.2) | −6.0 (−32.7, 12.0) | <0.001 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 393 | 9.0 (6.0, 12.0) | 116.4 (97.0, 139.0) | 104.0 (80.0, 129.5) | −11.9 (−35.0, 12.0) | <0.001 | |

| HbA1c | All Study Population | 5109 | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 5.8 (5.5, 6.2) | 5.8 (5.4, 6.3) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.137 |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 2751 | 3.0 (1.0, 7.0) | 5.8 (5.5, 6.2) | 5.8 (5.5, 6.3) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.21 | |

| Male | 2358 | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 5.8 (5.5, 6.2) | 5.8 (5.4, 6.3) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) | 0.407 | |

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 3349 | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 5.8 (5.4, 6.2) | 5.8 (5.4, 6.2) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.15) | 0.528 | |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 1435 | 4.0 (2.0, 7.0) | 5.9 (5.5, 6.4) | 5.9 (5.5, 6.5) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.3) | 0.404 | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 325 | 5.0 (2.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (5.6, 6.5) | 6.0 (5.6, 6.8) | 0.0 (−0.3, 0.4) | 0.073 | |

| Total | N | % | Median (IQR) | p Value * | p Value ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit to Family doctor | All Study Population | 8170 | 8167 | 100.0% | 96.0 (59.0, 144.0) | - | - |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4370 | 4370 | 100.0% | 111.0 (73.0, 162.0) | 0.101 | <0.001 | |

| Male | 3800 | 3797 | 99.9% | 80.0 (47.0, 123.0) | |||

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5724 | 5721 | 99.9% | 92.0 (57.0, 139.0) | 0.527 | <0.001 | |

| Mod Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2047 | 2047 | 100.0% | 104.0 (63.0, 156.0) | |||

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 399 | 100.0% | 104.0 (63.0, 155.5) | |||

| Dietician Referrals | All Study Population | 8170 | 1171 | 14.3% | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | - | - |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4370 | 720 | 16.5% | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | <0.001 | 0.030 | |

| Male | 3800 | 451 | 11.9% | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |||

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5724 | 742 | 13.0% | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | <0.001 | 0.387 | |

| Mod Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2047 | 353 | 17.2% | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |||

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 76 | 19.0% | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |||

| Visit to diabetes specialist | All Study Population | 8170 | 342 | 4.2% | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | - | - |

| By Gender | |||||||

| Female | 4370 | 197 | 4.5% | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.121 | 0.176 | |

| Male | 3800 | 145 | 3.8% | 1.0 (1.0, 3.0) | |||

| By Risk | |||||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5724 | 192 | 3.4% | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | <0.001 | 0.038 | |

| Mod Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2047 | 115 | 5.6% | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | |||

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 35 | 8.8% | 2.0 (1.0, 4.5) |

References

- Lindsay, R.S.; Howard, B.V. Cardiovascular risk associated with the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2004, 4, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Dietz, W.H. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA 2002, 287, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athyros, V.G.; Ganotakis, E.S.; Elisaf, M.; Mikhailidis, D.P. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using the National Cholesterol Educational Program and International Diabetes Federation definitions. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2005, 21, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.S.; Giles, W.H.; Mokdad, A.H. Increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among U.S. Adults. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2444–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, M.; Bhuket, T.; Torres, S.; Liu, B.; Wong, R.J. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2003–2012. JAMA 2015, 313, 1973–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.S.; Li, C.; Sattar, N. Metabolic syndrome and incident diabetes: Current state of the evidence. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amouzegar, A.; Honarvar, M.; Masoumi, S.; Khalili, D.; Azizi, F.; Mehran, L. Trajectory patterns of metabolic syndrome severity score and risk of type 2 diabetes. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hadaegh, F.; Abdi, A.; Kohansal, K.; Hadaegh, P.; Azizi, F.; Tohidi, M. Gender differences in the impact of 3-year status changes of metabolic syndrome and its components on incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: A decade of follow-up in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1164771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Amouzegar, A.; Honarvar, M.; Masoumi, S.; Agahi, S.; Azizi, F.; Mehran, L. Independent association of metabolic syndrome severity score and risk of diabetes: Findings from 18 years of follow-up in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e078701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aidarbekova, D.; Sadykova, K.; Saruarov, Y.; Nurdinov, N.; Zhunissova, M.; Babayeva, K.; Nemetova, D.; Turmanbayeva, A.; Bekenova, A.; Nuskabayeva, G.; et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Metabolic Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, P.W.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Parise, H.; Sullivan, L.; Meigs, J.B. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2005, 112, 3066–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannamethee, S.G.; Shaper, A.G.; Lennon, L.; Morris, R.W. Metabolic syndrome vs Framingham Risk Score for prediction of coronary heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 2644–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, J.L.; Ferrannini, E.; Grundy, S.M.; Haffner, S.M.; Heine, R.J.; Horton, E.S.; Kawamori, R.; Endocrine Society. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in patients at metabolic risk: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 3671–3689, Erratum in J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e2847. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Hansen, B.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Cleeman, J.I.; Kahn, R.A.; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Diabetes Association. Clinical management of metabolic syndrome: Report of the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Diabetes Association conference on scientific issues related to management. Circulation 2004, 109, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magkos, F.; Yannakoulia, M.; Chan, J.L.; Mantzoros, C.S. Management of the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes through lifestyle modification. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 29, 223–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guzmán, A.; Navarro, E.; Obando, L.; Pacheco, J.; Quirós, K.; Vásquez, L.; Castro, M.; Ramírez, F. Effectiveness of interventions for the reversal of a metabolic s yndrome diagnosis: An update of a meta-analysis of mixed treatment comparison studies. Biomedica 2019, 39, 647–662, (In English, Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cohen, A.D.; Gefen, K.; Ozer, A.; Bagola, N.; Milrad, V.; Cohen, L.; Abu-Hammad, T.; Abu-Rabia, Y.; Hazanov, I.; Vardy, D.A. Diabetes control in the Bedouin population in southern Israel. Med. Sci. Monit. 2005, 11, CR376–CR380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Treister-Goltzman, Y.; Peleg, R. Adolescent Obesity and Type Two Diabetes in Young Adults in the Minority Muslim Bedouin Population in Southern Israel. J. Community Health 2023, 48, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amkraut, J.; Zaina, A.; Abu-Rabia, Y. Diabetes in the Bedouin population in the Israeli Negev—An update 2017. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 140, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurka, M.J.; Filipp, S.L.; Musani, S.K.; Sims, M.; DeBoer, M.D. Use of BMI as the marker of adiposity in a metabolic syndrome severity score: Derivation and validation in predicting long-term disease outcomes. Metabolism 2018, 83, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sattar, N.; McConnachie, A.; Shaper, A.G.; Blauw, G.J.; Buckley, B.M.; de Craen, A.J.; Ford, I.; Forouhi, N.G.; Freeman, D.J.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Can metabolic syndrome usefully predict cardiovascular disease and diabetes? Outcome data from two prospective studies. Lancet 2008, 371, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. The incretin effect in healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes: Physiology, pathophysiology, and response to therapeutic interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamah, H.M.; Marey, A.; Abugdida, M.; Abualkhair, K.A.; Elshenawy, S.; Elhassan, W.A.F.; Naguib, M.M.; Malnev, D.; Durrani, J.; Bailey, R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on prediabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yanto, T.A.; Vatvani, A.D.; Hariyanto, T.I.; Suastika, K. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and new-onset diabetes in overweight/obese individuals with prediabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2024, 18, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Population (N = 8170) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Mean ± std (Median) | |

| Age (yrs) | 41.9 ± 6.2 | ||

| Gender (Female) | 4370 | 53.5% | |

| Metabolic Syndrome Criteria | |||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 4441 | 54.4% | 35.1 ± 4.5 |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose ≥ 100 | 3746 | 45.9% | 121.0 ± 29.9 |

| 150 ≤ Triglicerides ≤ 500 * | 6325 | 77.4% | 234.8 ± 74.3 |

| HDL Cholesterol: male < 40, female < 50 | 5880 | 72.0% | 37.3 ± 6.2 |

| Blood Pressure | |||

| Systolic ≥ 130 | 6442 | 78.8% | 150.2 ± 16.5 |

| Diastolic ≥ 85 | 5126 | 62.7% | 96.1 ± 9.1 |

| Risk Stratification | |||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5724 | 70.1% | |

| Mod Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2047 | 25.1% | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 4.9% | |

| Criteria | N | No. of Tests Median (IQR) (2008–2015) | Beginning of Study Median (IQR) | End of Study Median (IQR) | Change Median (IQR) | * p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 8045 | 7.0 (4.0, 11.0) | 31.6 (28.4, 35.3) | 31.6 (28.2, 35.4) | 0.15 (−1.21, 1.88) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides | 8163 | 9.0 (6.0, 12.0) | 184.0 (144.0, 240.0) | 165.0 (122.0, 223.0) | −13.0 (−64.0, 31) | <0.001 |

| Fasting Plasma Glucose | 8146 | 10.0 (6.0, 15.0) | 92.0 (81.0, 103.0) | 101.0 (92.0, 116.0) | 13.0 (0, 26.0) | <0.001 |

| HDL-c | 8164 | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | 40.0 (35.0, 46.0) | 41.0 (36.0, 48.0) | 1.0 (−3.0, 6.0) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 8131 | 11.0 (6.0, 18.0) | 126.0 (119.0, 136.0) | 126.0 (120.0, 134.0) | 0.0 (−11.0, 10) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 8132 | 11.0 (6.0, 18.0) | 80.0 (72.0, 85.0) | 78.0 (70.0, 83.0) | −1.0 (−10.0, 5.0) | <0.001 |

| Total Population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Patients with New T2DM Diagnosis | |||

| Group | N | % | p Value | |

| All Study Population | 8170 | 2093 | 26% | - |

| By Gender | ||||

| Female | 4370 | 1135 | 26% | 0.431 |

| Male | 3800 | 958 | 25% | |

| By Risk Group | ||||

| Low Risk (3/5 criteria) | 5724 | 1197 | 21% | <0.0001 |

| Moderate Risk (4/5 criteria) | 2047 | 700 | 34% | |

| High Risk (5/5 criteria) | 399 | 196 | 49% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Test, T.; Press, Y.; Freud, T.; Kannai, R.; Satran, R. Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Eight-Year Follow-Up Study in Southern Israel. Diabetology 2025, 6, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120150

Test T, Press Y, Freud T, Kannai R, Satran R. Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Eight-Year Follow-Up Study in Southern Israel. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120150

Chicago/Turabian StyleTest, Tsafnat, Yan Press, Tamar Freud, Ruth Kannai, and Robert Satran. 2025. "Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Eight-Year Follow-Up Study in Southern Israel" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120150

APA StyleTest, T., Press, Y., Freud, T., Kannai, R., & Satran, R. (2025). Metabolic Syndrome and Risk of New-Onset Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Eight-Year Follow-Up Study in Southern Israel. Diabetology, 6(12), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120150