Machine Learning for Causal Inference in Hospital Diabetes Care: TMLE Analysis of Selection Bias in Diabetic Foot Infection Treatment—A Cautionary Tale

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Cohort

2.2. Treatment Definition (Validation)

2.2.1. Clinical Curation

2.2.2. Technical Validation

2.3. Treatment Inclusion and Timing

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Restricted to non-inpatient settings (outpatient visits, emergency departments, office visits, and ambulatory care facilities; OMOP visit concept IDs: 9202, 9203, 581477, 38004208, 38004225, 38004247, 581479).

- -

- Occurred after initial DFI diagnosis date.

- -

- Associated with a concurrent DFI diagnosis during the same visit to ensure treatment relevance.

2.3.2. Treatment Timing

- -

- Early treatment: initiated within 3 days of first DFI diagnosis;

- -

- Delayed treatment: initiated ≥3 days after first DFI diagnosis;

- -

- No treatment: no documented DFI-specific treatment within the UCSF system.

2.3.3. Treatment Cutoff Validation

2.4. Exposure and Outcome

2.4.1. Exposure

2.4.2. Primary Outcome

2.4.3. Secondary Clinical Outcome

2.5. Covariates

- Demographics: age, gender, race (White, Black, Asian, other), Hispanic ethnicity;

- Clinical factors: diabetes type, MRSA colonization status;

- Comorbidities: chronic kidney disease, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral artery disease, osteomyelitis;

- Medications: anti-diabetic medication use, insulin vs. non-insulin classification;

- Laboratory values: albumin, serum creatinine, white blood cell count, hemoglobin A1c.

2.6. Causal Inference Approach

2.6.1. Notation

- A: Binary treatment indicator (A = 1 for early treatment within 3 days; A = 0 for delayed/no treatment);

- W: Vector of baseline covariates including demographics, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory values (19 covariates total);

- Y1: Binary primary outcome indicator (Y1 = 1 for DFI-related hospitalization; Y1 = 0 for no hospitalization);

- Y2: Binary secondary outcome indicator (Y2 = 1 for lower-extremity amputation; Y2 = 0 for no amputation).

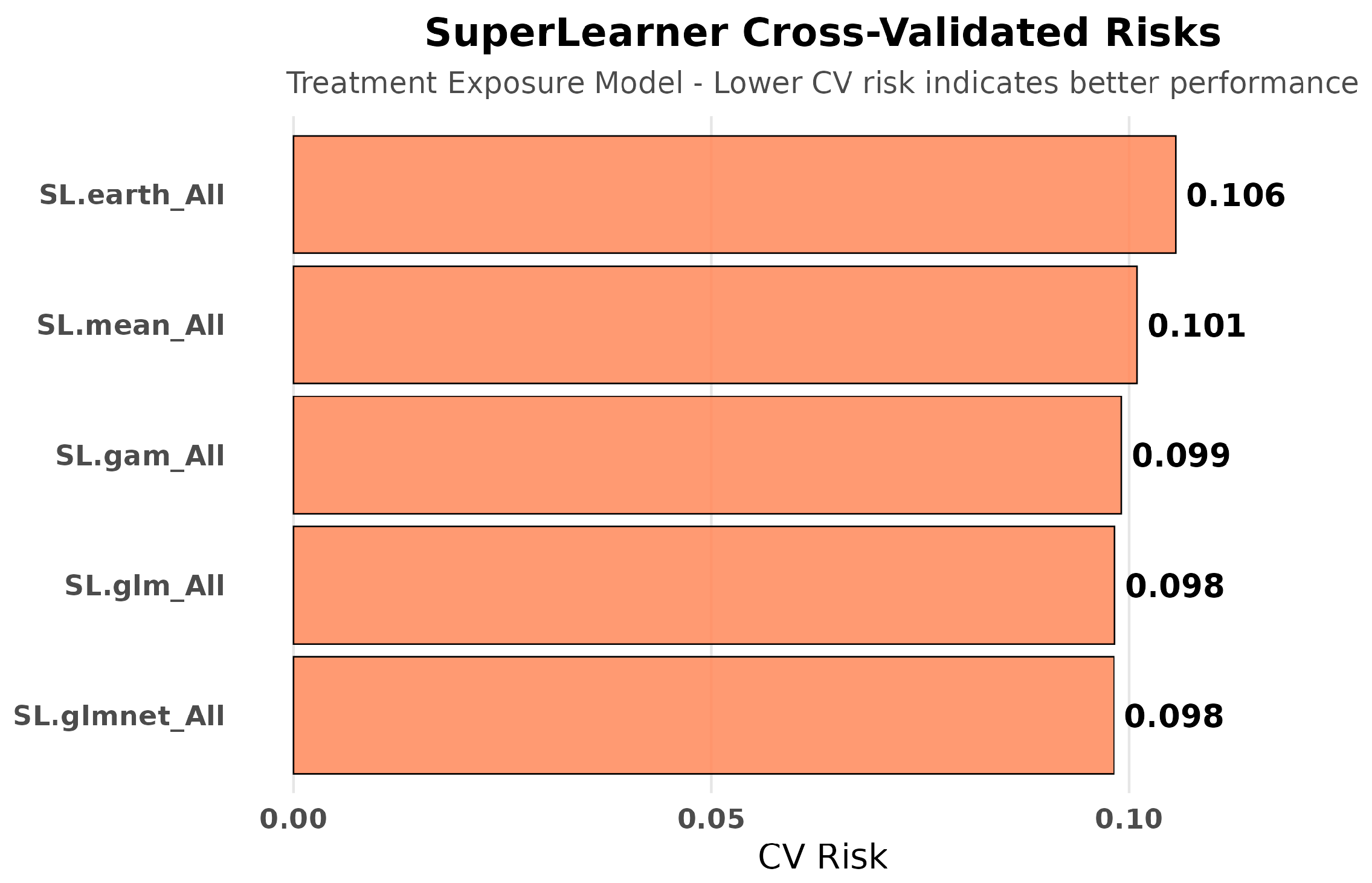

2.6.2. Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE)

- Outcome regression modeling: Estimated E[Y|A,W] using SuperLearner to predict outcome probability under both treatment conditions.

- Propensity score estimation: Estimated P(A = 1|W) using SuperLearner to model the probability of receiving early treatment given confounders.

- Targeted updating: Used clever covariates H(A,W) = A/P(A = 1|W) − (1 − A)/P(A = 0|W) to update the outcome model and reduce bias.

2.7. Addressing Baseline Group Differences

2.8. Statistical Inference

2.8.1. Estimation and Standard Errors

2.8.2. Bootstrap Confidence Intervals

2.8.3. Model Diagnostics

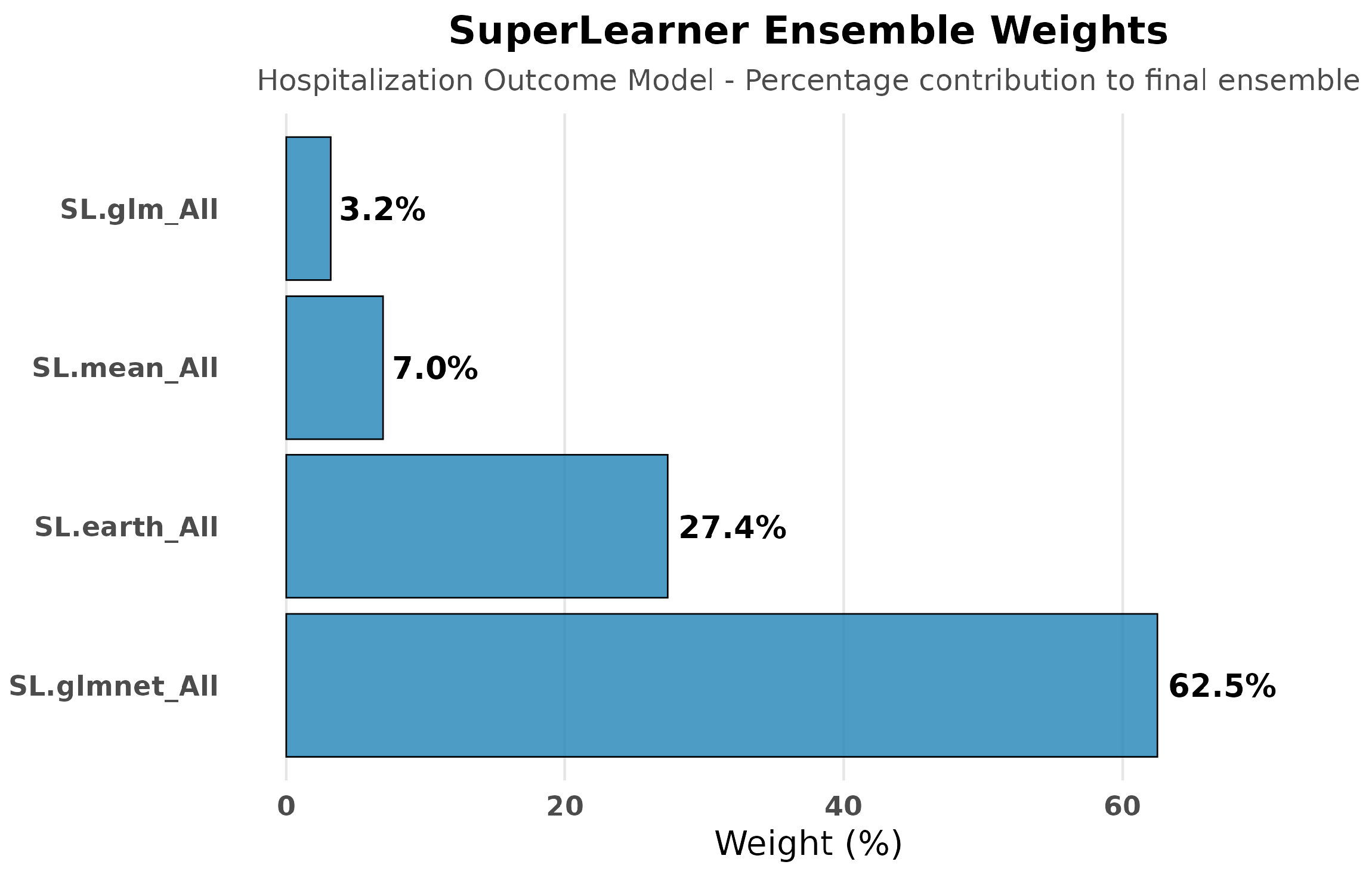

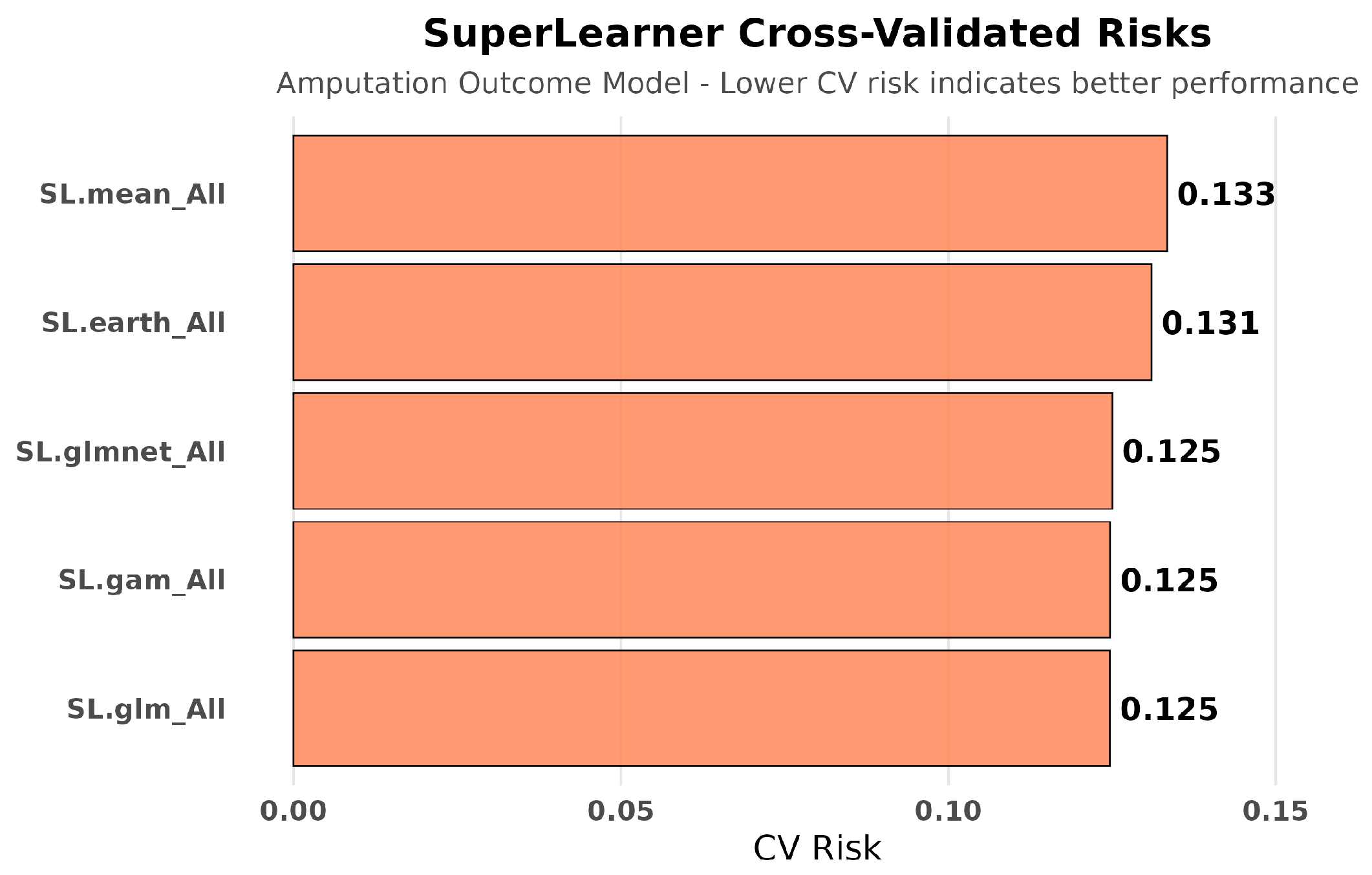

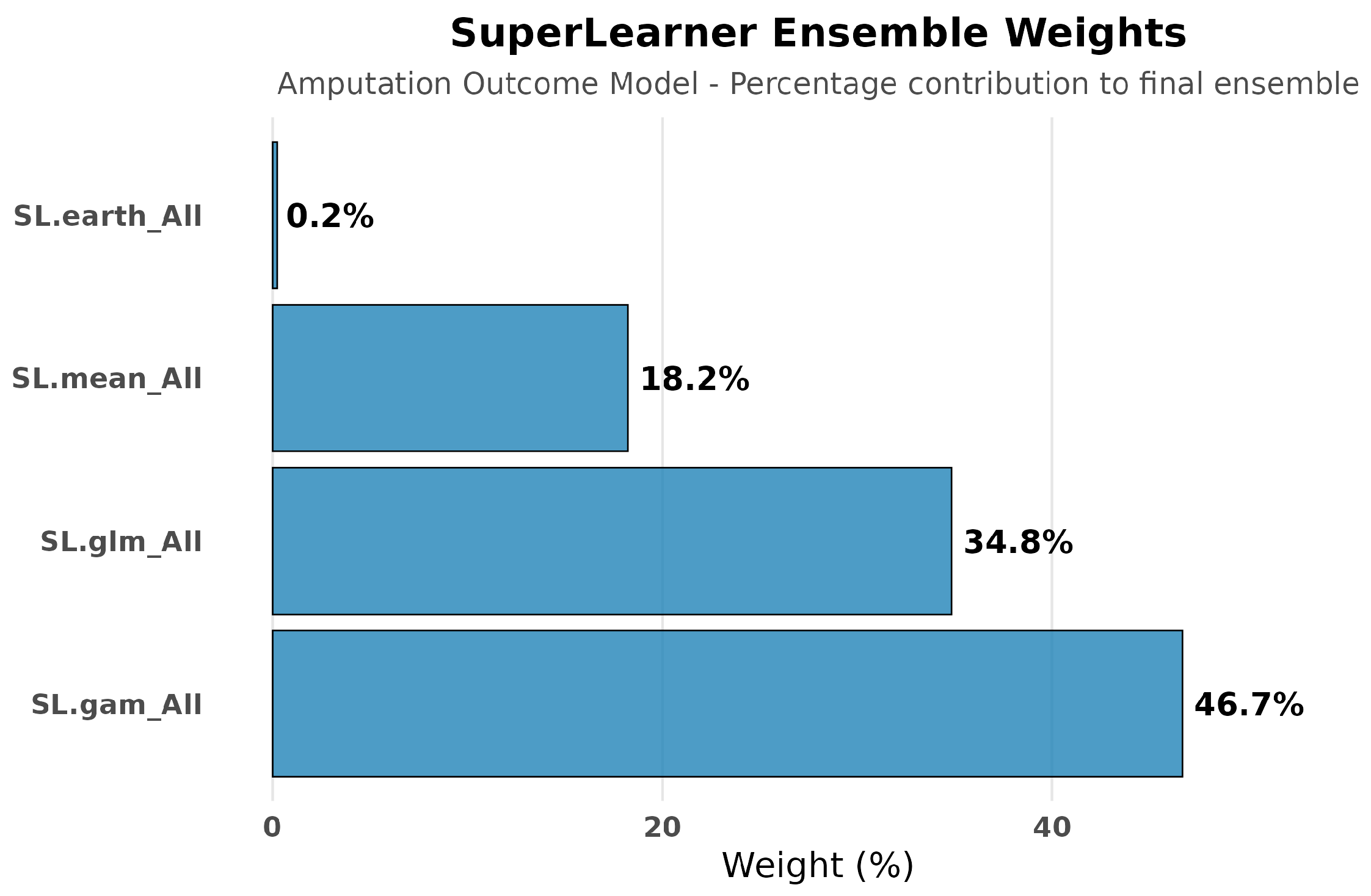

2.8.4. SuperLearner Ensemble

- -

- SL.glm (generalized linear models with all covariates);

- -

- SL.glmnet (elastic net regularization);

- -

- SL.gam (generalized additive models with smooth functions);

- -

- SL.earth (multivariate adaptive regression splines);

- -

- SL.mean (intercept-only baseline model).

2.8.5. Missing Data

2.8.6. Software

2.9. Subgroup Analyses

- -

- Ethnicity: Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic;

- -

- Glycemic control: A1c < 6.5% (good), ≥6.5% (poor), ≥8.0% (very poor);

- -

- Anti-diabetic medication use: taking vs. not taking;

- -

- Laboratory thresholds: WBC > 11.0 K/μL, albumin > 3.5 g/dL.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Treatment Patterns

3.2. Baseline Characteristics and Treatment Selection

- Higher glycemic dysfunction: A1c levels were significantly elevated (8.43 ± 2.52% vs. 7.75 ± 2.15%, p = 0.002);

- Increased infection risk: MRSA colonization was more than twice as prevalent (10.4% vs. 4.7%, p = 0.004);

- Greater diabetes complexity: Anti-diabetic medication use was nearly universal (93.9% vs. 71.8%, p < 0.001).

3.3. Primary Outcomes

3.3.1. Causal Effect Estimates

- Risk Difference: 0.293 (95% CI: 0.220–0.367, p < 0.001);

- Risk Ratio: 1.88 (95% CI: 1.72–2.09).

3.3.2. Robustness Across Methods

- G-computation: Risk difference = 0.244;

- Inverse probability weighting: Risk difference = 0.233.

3.3.3. Sensitivity and Validation Analyses

Sensitivity Analysis

Bootstrap Validation

- Simple Substitution: Mean bootstrap estimate = 0.244 (range: 0.116–0.387);

- IPW: Mean bootstrap estimate = 0.181 (range: 0.072–0.938);

- TMLE: Mean bootstrap estimate = 0.306 (range: 0.162–0.452).

- Simple Substitution: 15.5–33.2% (normal), 15.7–33.8% (quantile);

- IPW: 11.5–35.2% (normal), 9.9–27.1% (quantile);

- TMLE: 19.6–39.1% (normal approximation), 20.5–39.6% (quantile method).

3.3.4. Effect Modification Analysis

Glycemic Control Status

- Good control (A1c < 6.5%): No significant association (RD = 0.08, 95% CI: −0.11–0.27, p = 0.40);

- Poor control (A1c ≥ 6.5%): Strong association (RD = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.27–0.43, p < 0.001);

- Very poor control (A1c ≥ 8.0%): Moderate association (RD = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.16–0.42, p < 0.001).

Ethnic Disparities

- Hispanic: RD = 0.43 (95% CI: 0.30–0.56, p < 0.001);

- Non-Hispanic: RD = 0.26 (95% CI: 0.18–0.35, p < 0.001).

Medication Use Patterns

- Not on medications: RD = 0.34 (95% CI: 0.22–0.46, p < 0.001);

- Taking medications: RD = 0.23 (95% CI: 0.16–0.31, p < 0.001).

Laboratory Markers

- Elevated WBC (>11.0 K/μL): No significant association (RD = 0.14, 95% CI: −0.06–0.33, p = 0.16);

- Normal/low WBC (≤11.0): Strong association (RD = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.22–0.39, p < 0.001).

- High albumin (>3.5 g/dL): Moderate association (RD = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.08–0.41, p = 0.004);

- Normal/low albumin (≤3.5): Strong association (RD = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.24–0.39, p < 0.001).

3.3.5. Model Performance and Diagnostics

Propensity Score Assessment

- Mean propensity scores: 0.151 for early-treated vs. 0.109 for delayed/untreated patients;

- Range: 0.036 to 0.423, indicating reasonable but not complete overlap;

- Positivity concerns: 573 patients (40.0%) had propensity scores below 0.1, suggesting limited comparability between groups and potentially reduced precision, particularly in subgroup analyses.

Weight Distribution

- Mean absolute weight: 1.89;

- Maximum weight: 23.4;

- Extreme weights (>10): 28 patients (2.0% of sample).

SuperLearner Performance

- Best performing: SL.glmnet (risk = 0.209) and SL.glm (risk = 0.209);

- Flexible modeling: SL.gam (risk = 0.210) and SL.earth (risk = 0.217);

- Baseline: SL.mean (risk = 0.232).

3.4. Secondary Clinical Outcomes: Lower-Extremity Amputation

3.4.1. Causal Effect Estimates

3.4.2. Sensitivity and Validation Analyses

3.4.3. Super Learner Performance for Amputation

3.4.4. Clinical Interpretation

4. Discussion

4.1. External Care and Exposure Misclassification

4.2. Confounding by Indication: Why Increased Hospitalization Does Not Mean Treatment Harm

4.3. Effect Modification Reveals Clinical Complexity

4.4. Divergent Clinical Outcomes (Hospitalization vs. Amputation)

4.5. Implications for Clinical Decision Support and EHR-Based Research

4.6. Limitations

4.6.1. Data Completeness and External Validity

4.6.2. Clinical Severity Assessment

4.6.3. Methodological Constraints

4.6.4. Measurement and Classification Issues

4.7. A Cautionary Tale for Healthcare Analytics

5. Conclusions

5.1. Overall Findings

5.2. Future Research Imperatives

5.3. Final Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFI | Diabetic foot infection |

| TMLE | Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| EHR | Electronic health record |

| UCSF | University of California, San Francisco |

| OMOP | Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership |

| LEA | Lower extremity amputation |

| IPW | Inverse probability weighting |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| A1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| WBC | White blood cell |

| PEDIS | Perfusion, Extent, Depth, Infection, Sensation |

References

- Waibel, F.W.A.; Uckay, I.; Soldevila-Boixader, L.; Sydler, C.; Gariani, K. Current knowledge of morbidities and direct costs related to diabetic foot disorders: A literature review. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1323315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.N.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincke, B.G.; Miller, D.R.; Turpin, R. A classification of diabetic foot infections using ICD-9-CM codes: Application to a large computerized medical database. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frykberg, R.G.; Wittmayer, B.; Zgonis, T. Surgical management of diabetic foot infections and osteomyelitis. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 2007, 24, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathnayake, A.; Saboo, A.; Malabu, U.H.; Falhammar, H. Lower extremity amputations and long-term outcomes in diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review. World J. Diabetes 2020, 11, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primadhi, R.A.; Septrina, R.; Hapsari, P.; Kusumawati, M. Amputation in diabetic foot ulcer: A treatment dilemma. World J. Orthop. 2023, 14, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, A.; Lebowitz, D.; Gariani, K.; Abbas, M.; Kressmann, B.; Assal, M.; Uçkay, I. Stopping antibiotics after surgical amputation in diabetic foot and ankle infections—A daily practice cohort. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2019, 2, e00059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.; Vileikyte, L.; Ragnarson-Tennvall, G.; Apelqvist, J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005, 366, 1719–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Thomas, G.N.; Gill, P.; Torella, F. The prevalence of major lower limb amputation in the diabetic and non-diabetic population of England 2003–2013. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2016, 13, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prompers, L.; Huijberts, M.; Schaper, N.; Apelqvist, J.; Bakker, K.; Edmonds, M.; Holstein, P.; Jude, E.; Jirkovska, A.; Mauricio, D.; et al. Resource utilisation and costs associated with the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Prospective data from the Eurodiale Study. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1826–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.; Rayman, G.; Jeffcoate, W.J. Cost of diabetic foot disease to the National Health Service in England. Diabetes Med. 2014, 31, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Swerdlow, M.A.; Armstrong, A.A.; Conte, M.S.; Padula, W.V.; Bus, S.A. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2020, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, C.M.; Sugita, T.H.; Rosa, M.Q.M.; Pedrosa, H.C.; Rosa, R.D.S.; Bahia, L.R. Annual direct medical costs of diabetic foot disease in Brazil: A cost of illness study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wukich, D.K.; Ahn, J.; Raspovic, K.M.; Gottschalk, F.A.; La Fontaine, J.; Lavery, L.A. Comparison of transtibial amputations in diabetic patients with and without end-stage renal disease. Foot Ankle Int. 2017, 38, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.G.; Tan, T.W.; Boulton, A.J.; Bus, S.A. Diabetic foot ulcers: A review. JAMA 2017, 318, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrepnek, G.H.; Mills, J.L., Sr.; Lavery, L.A.; Armstrong, D.G. Health Care Service and Outcomes Among an Estimated 6.7 Million Ambulatory Care Diabetic Foot Cases in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C.W.; Selvarajah, S.; Mathioudakis, N.; Sherman, R.E.; Hines, K.F.; Black, J.H.; Abularrage, C.J. Burden of Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers on Hospital Admissions and Costs. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 33, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. In 2007. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-W.; Yang, H.-M.; Hung, S.-Y.; Chen, I.-W.; Huang, Y.-Y. The Analysis for Time of Referral to a Medical Center among Patients with Diabetic Foot Infection. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.J.; Rose, S. Targeted Learning: Causal Inference for Observational and Experimental Data; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.L.; Porter, K.E.; Gruber, S.; Wang, Y.; van der Laan, M.J. Diagnosing and responding to violations in the positivity assumption. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2012, 21, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.J.; Polley, E.C.; Hubbard, A.E. Super Learner. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, M.L.; van der Laan, M.J. Causal Models and Learning from Data: Integrating Causal Modeling and Statistical Estimation. Epidemiology 2014, 25, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Delayed/No Treatment (n = 1271) | Early Treatment (n = 163) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age years (mean ± SD) | 68.13 ± 13.27 | 67.53 ± 13.73 | 0.589 |

| Male gender | 909 (71.5%) | 115 (70.6%) | 0.869 |

| Race | |||

| White | 600 (47.2%) | 82 (50.3%) | 0.507 |

| Asian | 171 (13.5%) | 27 (16.6%) | 0.335 |

| Other | 500 (39.3%) | 54 (33.1%) | 0.148 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 275 (21.6%) | 22 (13.5%) | 0.021 * |

| Clinical Factors | |||

| Type 1 diabetes | 74 (5.8%) | 11 (6.7%) | 0.768 |

| MRSA colonization | 60 (4.7%) | 17 (10.4%) | 0.004 * |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 680 (53.5%) | 82 (50.3%) | 0.493 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 652 (51.3%) | 79 (48.5%) | 0.55 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 497 (39.1%) | 66 (40.5%) | 0.798 |

| Osteomyelitis | 427 (33.6%) | 62 (38.0%) | 0.299 |

| Anti-diabetic medications | 913 (71.8%) | 153 (93.9%) | <0.001 * |

| Laboratory values (mean ± SD) | |||

| Hemoglobin A1c % | 7.75 ± 2.15 | 8.43 ± 2.52 | 0.002 * |

| Albumin g/dL | 3.18 ± 0.76 | 3.13 ± 0.71 | 0.501 |

| Serum creatinine mg/dL | 10.47 ± 31.04 | 8.22 ± 31.65 | 0.613 |

| WBC count K/μL | 6.74 ± 4.85 | 6.03 ± 5.72 | 0.108 |

| Estimator | Mean RD | 95% CI (Normal) | 95% CI (Quantile) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | 24.40% | [15.5–33.2%] | [15.7–33.8%] | Simple Substitution |

| IPW | 23.30% | [11.5–35.2%] | [9.9–27.1%] | Inverse Probability Weighting |

| TMLE | 29.30% | [19.6–39.1%] | [20.5–39.6%] | Targeted Maximum Likelihood |

| Estimator | Mean RD | 95% CI (Normal) | 95% CI (Quantile) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | −3.8% | [−8.3–0.8%] | [−7.9–0.4%] | Simple Substitution |

| IPW | −4.8% | [−11.3–1.6%] | [−10.7–1.1%] | Inverse Probability Weighting |

| TMLE | −4.0% | [−12.4–4.4%] | [−9.8–6.6%] | Targeted Maximum Likelihood |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hur, R.; Rushakoff, R. Machine Learning for Causal Inference in Hospital Diabetes Care: TMLE Analysis of Selection Bias in Diabetic Foot Infection Treatment—A Cautionary Tale. Diabetology 2025, 6, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110122

Hur R, Rushakoff R. Machine Learning for Causal Inference in Hospital Diabetes Care: TMLE Analysis of Selection Bias in Diabetic Foot Infection Treatment—A Cautionary Tale. Diabetology. 2025; 6(11):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110122

Chicago/Turabian StyleHur, Rim, and Robert Rushakoff. 2025. "Machine Learning for Causal Inference in Hospital Diabetes Care: TMLE Analysis of Selection Bias in Diabetic Foot Infection Treatment—A Cautionary Tale" Diabetology 6, no. 11: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110122

APA StyleHur, R., & Rushakoff, R. (2025). Machine Learning for Causal Inference in Hospital Diabetes Care: TMLE Analysis of Selection Bias in Diabetic Foot Infection Treatment—A Cautionary Tale. Diabetology, 6(11), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6110122