1. Introduction

HCC, which accounts for 80–85% of liver cancers, is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally [

1]. Despite surgical resection, it has a high recurrence rate, and limited treatment options for unresectable cases result in poor prognosis [

2]. ITH, driven by genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental factors, has been identified as a significant driver of tumor progression, metastasis, and therapeutic failure [

3]. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the ITH in HCC is crucial.

scRNA-seq technology has enabled unbiased analysis of the transcriptional profiles of tumor cells, revealing significant heterogeneity among malignant cells [

4]. This approach has been applied in various cancers such as glioblastoma [

5], oligodendroglioma [

6], astrocytoma [

7], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [

8], and melanoma [

9]. In melanoma, the skin pigmentation process driven by MITF and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) process associated with AXL showed distinct differences in individual tumors and were closely related to patient prognosis [

10]. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, EMT-like and epithelial senescence programs have been identified, influencing metastatic potential and drug response [

8,

11]. Studies have also revealed tumor-associated gene modules that are widely present across cancers [

12,

13]. However, research on gene modules associated with ITH in HCC remains limited, and their spatial interactions with TME have yet to be comprehensively elucidated.

In this study, we integrated scRNA-seq and ST to comprehensively dissect ITH in HCC and its spatial influence on the TME. Using NMF-based program decomposition, we identified seven non-mutually exclusive malignant cell states that contribute to transcriptional complexity. By mapping these programs onto ST data, we revealed eight spatial niches with distinct immune and stromal architectures. Notably, we uncovered a hypoxia–VEGFA+ CAF–PLVAP+ EC axis that may drive pro-angiogenic remodeling and characterized boundary zones enriched in interferon-high tumor cells, DC1, and polarized macrophages (CXCL10+ and SPP1+) with spatially distinct roles. These findings offer a spatially resolved framework for understanding how ITH shapes local TME composition and function, providing mechanistic insights with potential relevance for precision therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

We utilized 79 scRNA-seq samples of HCC from the study by Xue et al. [

14]. to construct a large-scale HCC scRNA-seq database. The raw FASTQ data were obtained from the China National Center for Bioinformation (

https://www.cncb.ac.cn/) with BioProject ID PRJCA007744. In addition, five HCC patient samples (tumor tissues only) from the study by Wu et al. [

15] provided seven slides, which formed the basis for our ST study cohort.

2.2. scRNA-Seq Data Processing

After filtering the scRNA-seq FASTQ data, we performed alignment using Starsolo (v2.7.9a) with the human reference genome GRCh38. For the resulting raw gene expression matrix, we used decontX (v1.0.0) [

16] to remove potential contamination. Next, we conducted filtering, dimensionality reduction, and clustering analysis using Seurat (v4.3.0) [

17]. The filtering criteria included the following: (1) the number of genes detected in each cell was between 500 and 6000; (2) the number of UMIs in each cell ranged from 1000 to 30,000; (3) the mitochondrial gene content was below 10%. We selected 2000 highly variable genes and used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimension of the log-normalized expression matrices of all samples. To remove batch effects, we used Harmony (v1.2.0) to correct the PCA results, with patient labels as covariates. A Shared Nearest Neighbor (SNN) graph was constructed using the first 30 principal components with the FindNeighbors function in Seurat, and cells were clustered using the Louvain algorithm with the FindClusters function. Dimensionality reduction and visualization were performed using the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) method. For each cell subtype, we performed further dimension reduction and clustering analysis to obtain more refined clustering results while removing potential contamination from other cell types. RNA-based copy number variation (CNV) inference was conducted on the presumed malignant cell clusters using the infercnvpy (v0.5.0) package, with all other cells as the reference, to identify consistent patterns of copy number variation. To reduce label transfer bias, key cell subtypes such as VEGFA

+ CAF were cross-validated using external HCC scRNA-seq datasets in our previous study [

18].

2.3. NMF Analysis

2.3.1. Identification of Modules

For each sample in the dataset, we first extracted the scaled gene expression data using the GetAssayData () function. The data was filtered to include only the variable genes (using VariableFeatures ()), and any negative values were set to zero. Additionally, genes with zero variance across samples were removed to improve the robustness of the analysis. NMF was performed on the preprocessed data for each sample with NMF package (v0.27), iterating over a range of rank values (i.e., the number of components to be extracted). For each rank, the NMF was run using the nmf () function from the nsNMF method with a single run (nrun = 1) and a seed for reproducibility (seed = ‘ica’). After obtaining the NMF decomposition for each sample, we used the NMFToModules function to identify gene modules. This function processes the basis matrix (which represents the weight of each gene in the identified components) to classify genes into distinct modules based on their ranking in the NMF decomposition.

Modules were defined by sorting genes in each component and selecting those with a rank of 1 tothe length of the component. The size of each module was filtered based on a threshold (gmin = 5), ensuring that only modules containing a sufficient number of genes were retained. To determine the optimal number of components (rank) for the NMF decomposition, the number of modules identified in each decomposition was compared. The rank yielding the smallest difference between the expected number of modules and the actual count was selected. This ensured that the rank chosen provided a balance between model complexity and biological relevance. Once the optimal rank was determined, the corresponding NMF decomposition was selected, and the modules were re-extracted using the NMFToModules function. These modules were then used for downstream analyses to investigate their functional relevance in the tumor microenvironment.

2.3.2. Graph-Based Clustering and Identification of Consensus Gene Modules

For each identified gene module in the result list, we calculated the overlap with other gene modules. The overlap between two gene modules was defined as the ratio of the number of genes shared between the two modules over the total number of genes in both modules. Modules were retained if they exhibited at least 5% overlap with other modulesin at least three other distinct modules. Specifically, we computed the intersection and union of gene sets for each module, calculating the overlap similarity using Jaccard similarity.

For each sample we built an adjacency matrix where each entry represented the number of times two genes appeared in the same module across different samples. We only considered gene pairs that appeared in at least two separate tumor modules. The adjacency matrix was initialized with zeros, and for each tumor sample, genes that appeared in a module were iterated over, with the matrix values incremented for each pair of genes found together. To reduce noise and irrelevant connections, gene pairs with fewer than two occurrences across different tumor modules were removed. We further refined the connectivity matrix by keeping only those genes with a minimum number of connections across tumor samples (with a threshold of s_min = 3), thereby removing genes with low connectivity.

We treated the filtered adjacency matrix as an undirected weighted graph, where each gene was represented as a node and the gene-to-gene connections were edges weighted by the frequency of co-occurrence in tumor modules. This graph was constructed using the graph_from_adjacency_matrix () function, with the mode = ‘undirected’ to capture the bidirectional nature of gene interactions. To identify communities within the graph, we applied the Infomap algorithm (cluster_infomap ()) for community detection. This method is suitable for detecting highly connected clusters of genes that may represent functional modules. We performed the clustering with 100 trials to ensure robust community detection. Only modules with more than 10 genes were retained for further analysis. To address potential instability in NMF decomposition, we used a fixed initialization strategy (seed = ‘ica’) and performed NMF independently for each sample. We then constructed a cross-sample gene co-occurrence graph and applied Infomap clustering to extract robust modules supported by recurrent patterns across patients. This strategy improves reproducibility and filters out decomposition noise, ensuring module stability.

2.3.3. Module Annotation

We used terms from the MSigDB package and tumor-related gene modules identified in pan-cancer studies by Barkley et al. [

12] and Avishai Gavish et al. [

13] as reference databases. We calculated the statistical significance of the overlap between each module and each downloaded gene set using their hypergeometric distribution to determine whether the observed overlap occurred by chance, thereby identifying an annotation for each gene module. We applied strict module size and connectivity thresholds, followed by graph-based clustering and functional enrichment, to minimize spurious modules and ensure biological relevance.

2.4. ST Data Processing

The ST gene expression matrix was obtained from the raw data provided by Wu et al. The filtering criteria included the following: (1) spots with fewer than 300 measured genes or fewer than 500 UMIs were filtered out; (2) ribosomal and mitochondrial genes were excluded from this analysis. The SCTransform method was used to normalize the individual count matrices, and additional log-normalization (size factor = 10,000) and ratio matrices were computed for comparative analysis using the default settings.

Cell2location (v0.1.3) [

19] was used to calculate the cell type composition for each spot. Using regularized negative binomial regression and our integrated scRNA-seq profile, we evaluated the reference expression features for major cell types. We fitted the model across six down-sampling iterations of our snRNA-seq profile and generated the final reference matrix by averaging the estimates. Each slide was later deconvoluted using the hierarchical Bayesian model implemented in run_cell2location. Notably, we assessed the proportions of low-resolution and high-resolution cell types in the spots by utilizing both major cell subtype labels (14 cell groups) and higher-resolution cell subtype labels (48 cell subtypes). For each spot, we estimated signaling pathway activities with progeny (v1.24.0) [

20].

2.5. Spatial Map of Cell Dependencies

We utilized mistyR (v1.10.0) [

21] to assess how the abundance of each major cell type contributed to the abundance of other cell types. The cell-type estimations from cell2location across all slides were modeled using a multi-view approach, incorporating three spatial contexts: (1) an intrinsic view that captures relationships within a spot based on deconvolution estimations, (2) a juxta view that sums deconvolution estimations from neighboring spots (maximum distance threshold = 5), and (3) a para view that weights estimations from more distant neighbors (effective radius = 15 spots). The median of the aggregated standardized importance from each spatial view was used to represent cell-type dependencies in different spatial contexts, such as colocalization or mutual exclusion. We excluded predictors with an R

2 value below 10% for each slide before aggregating the results.

To link tissue structures to tissue functions, we applied the misty model to explain the distribution of progeny pathway activity scores. This model also incorporated three spatial views: (1) an intrinsic view to model pathway crosstalk within a spot, (2) a juxta view to capture pathway interactions between neighboring spots (largest distance threshold = 5), and (3) a para view that models pathway relationships in larger tissue regions (effective radius = 15). Additionally, two views incorporating cell2location estimations (intrinsic and para views with an effective radius of 15) were used to model relationships between cell-type compositions and pathway activities. As with the previous aggregation, predictors with an R2 less than 10% were excluded before summarization. To control for cell composition confounding in pathway activity inference, we used PROGENy and multiview modeling with mistyR to disentangle pathway activation from cell-type abundance.

All misty models were trained jointly across the seven spatial transcriptomic slides, with all spatial spots included in a unified analysis framework. This joint modeling approach increased statistical power and improved the robustness of the inferred spatial dependencies across patients.

2.6. Niche Definitions and Analysis

2.6.1. ISCHIA

To identify the niche in HCC, we used ISCHIA [

22]. The optimal number of clusters was determined by the elbow method based on the average clustering variance within the range of k values from 2 to 20. The final selection was k = 8 as the optimal number of clusters. Then, using the Composition.cluster () function, we classified all the spots into eight niches based on the abundance of cell types in each spot (obtained through deconvolution).

2.6.2. Multimodal Intersection Analysis (MIA)

We first calculated the highly expressed genes for each cell type in the single-cell data using the FindAllMarkers function and then calculated the highly expressed genes for each compositional cluster in the spatial transcriptomic data. Next, we used the hypergeometric distribution test to evaluate whether the gene overlap between each cell type and each compositional cluster was statistically significant.

2.6.3. SPATA2

We used the R package SPATA2 (v3.1.2) [

23] to evaluate the spatial gradient relationships between various cell types in HCC. Using the createNumericAnnotations function, we automatically annotated regions with higher abundances of the target cell type. If any regions were missed, we manually supplemented the annotations. We then used the getCoordsDfSA function to calculate the distance between any spot and the annotated region. To study how cell abundance varies with spatial changes, we used the spatial Annotation Screening function to compute the trend of cell type abundance changes with distance. We also created supervised spatial trajectories using the create Spatial Trajectories function, designed to traverse immune infiltration and boundary regions. The spatial Trajectory Screening function was subsequently used to monitor the changes in cell type abundance along this axis.

2.6.4. Cottrazm

We defined tumor boundaries using Cottrazm (v0.1.1) [

24] and explored whether they aligned with the boundaries we defined. First, we obtained CNV scores for all spots in the target tissue slice using STInferCNV and STCNVScore, followed by clustering analysis. We then further defined the tumor boundaries using the Boundary Define function.

2.6.5. Cytospace

Using Cytospace [

25], we mapped individual cells from the scRNA-seq data onto the spatial slides, enabling us to study the spatial distribution of cells at a single-cell resolution. First, we created a single-cell expression matrix and corresponding cell labels using the generate_cytospace_from_scRNA_seurat_object function. Then, we mapped the single-cell data onto each spot using the cytospace function, resulting in a spatial map with single-cell resolution. Notably, we performed the mapping for both major cell types and higher-resolution subgroups.

2.7. Cell Preference Analysis

To assess the prevalence of distinct cell types across different tissues, we used Ro/e, which represents the ratio of observed to expected cell counts. An Ro/e greater than 1 indicates enrichment of a specific cell cluster within a tissue, while an Ro/e less than 1 indicates depletion.

2.8. Functional Enrichment Analysis

To explore the functional characteristics of different cell subpopulations, we first identified the top highly expressed genes in each subpopulation using the FindAllMarkers function (adjusted p < 0.05, log2FC > 0.25). We then performed functional enrichment analysis of the top 50 genes for each subpopulation, utilizing the GO and KEGG databases via the clusterProfiler R package (v4.10.0), with a significance threshold of FDR < 0.05, which was called Over-Representation Analysis (ORA).

Furthermore, to provide a more unbiased functional evaluation of the cell types, we also employed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA). GSEA is a computational method that assesses whether predefined gene sets show statistically significant differences in expression between two conditions. By ranking genes based on their expression levels and testing whether members of a gene set are disproportionately represented at the extremes of the ranked list, GSEA provides insights into pathway-level changes in biological systems. We used the clusterProfiler R package to perform GSEA on our data, which allowed us to examine the enrichment of various biological pathways and gene sets. For the single-cell data, functional scoring of each cell was conducted using the addModuleScore function.

3. Results

3.1. Atlas of Sc-RNAseq in HCC

To explore the ITH of HCC and its corresponding TME, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the large-scale scRNA-seq data from 79 untreated HCC samples. After excluding 1 anomalous sample and performing cell quality control (

Supplementary Figure S1A), a total of 319,040 cells from 78 HCC samples were included in the analysis. To eliminate batch effects, we applied the Harmony algorithm for data correction and performed clustering analysis based on the integrated scRNA-seq data, identifying eight major cell types (

Figure 1A–C;

Supplementary Figure S1B; Supplementary Table S1): B cells (marked by CD79A, MS4A1,

n = 8186), plasma cells (marked by IGKC, IGHG1,

n = 4184), T cells (marked by CD3D, CD3E,

n = 146,150), NK cells (marked by NKG7, KLRD1,

n = 18,335), endothelial cells (marked by PECAM1, VWF,

n = 36,412), mesenchymal cells (marked by RGS5, COL1A1,

n = 18,720), myeloid cells (marked by CD14, C1QB,

n = 67,253), and epithelial cells (marked by APOA2, KRT18,

n = 19,780).

We explored the distribution patterns of cell subpopulation in the tumor samples, and the results showed that after batch effect elimination, there were no sample-specific cell type distributions (

Supplementary Figure S1C,D). Copy number variation (CNV) analysis revealed that epithelial cells exhibited significantly higher levels of copy number variations compared to other cell subpopulations, which was consistent with the expected results (

Supplementary Figure S1E). For non-epithelial cell subpopulations, we conducted further dimensionality reduction and clustering analysis, identifying various cell clusters, including twelve T cell clusters, two NK cell clusters (

Supplementary Figure S1F), six B cell clusters, one plasma cell cluster (

Supplementary Figure S1G), four Mac clusters, two monocyte (Mono) clusters, one neutrophil (Neu) cluster, three DC clusters (

Supplementary Figure S1H), five EC clusters, and five mesenchymal cell clusters (

Supplementary Figure S1I).

In summary, through both coarse and fine cell clustering analysis, we have preliminarily explored the cellular composition characteristics of the HCC TME, laying a solid foundation for further research.

3.2. Identification and Annotation of Modules

To explore gene modules in HCC, we performed NMF analysis on malignant cells of every sample (

Supplementary Figure S2A). Ultimately, we constructed seven common gene modules that were highly recurrent across HCC patients, with each module containing between 12 and 126 genes (

Supplementary Table S1). To explore the biological function of these modules, we used the hypergeometric distribution test to compare the modules with gene terms from multiple databases (

Figure 2A,B;

Supplementary Figure S2B–D).

In our analysis, we identified a module containing cell cycle-related genes (such as TOP2A, PCNA, MKI67). As expected, these genes were highly consistent with cell-cycle-related terms across five databases, reflecting the proliferation characteristics of HCC tumor cells. Another module contained genes significantly associated with hypoxia, such as ADM, BNIP3, and EGLN3. This module showed a strong correspondence with the hypoxia-related modules defined by Dalia Barkley et al. [

12] and Avishai Gavish et al. [

13], indicating that hypoxia is a common feature in cancer and plays a key role in tumors. Additionally, we defined a module that contained not only malignant epithelial marker genes (such as KRT18, KRT8) but also stromal-related genes (such as COL1A2, ENG, PLVAP). This suggests that cancer cells might be undergoing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), exhibiting both epithelial and mesenchymal features. The interferon response module was widely detected across multiple samples, containing interferon-related genes (such as STAT1, ISG15) and antigen-presentation-related genes (such as HLA-A, HLA-DRB1). Notably, although MHCII expression is typically associated with professional antigen-presenting cells, this pathway is also expressed in normal epithelial and cancer cells [

26]. We also identified a module related to protein synthesis, containing genes like CALR and PDIA3. This module aligned with the protein maturation and unfolded protein response modules defined by Avishai Gavish et al. [

13]. Furthermore, we discovered a metabolism-related module involving lipid metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, and drug metabolism, with relevant genes such as ACAT2 and ACSL1. The functional characteristics of this module remind us of the normal liver function, suggesting that despite undergoing carcinogenesis, tumor cells may still retain some normal liver tissue functions. Finally, we identified a stress response-related module, containing genes such as DDIT3 and DDIT4, reflecting the process by which tumor cells maintain homeostasis in response to environmental stress through molecular and cellular functional changes [

27].

To explore the expression patterns of different gene modules in individual cells, we scored the expression of each module in malignant cells. For each module, we presented its expression in all cells; cells with a module score of 0 were shown in gray (

Figure 2C). The results revealed that cells did not express only a specific module but rather co-expressed multiple modules. We classified tumor cells based on seven module scores; the highest scoring module for each cell was used as its label, named as “Mal_”, followed by the module name, reflecting the malignant nature of the cell. In the end, we identified 1683 Mal_Cell_cycle cells, 1733 Mal_EMT cells, 1054 Mal_Hypoxia cells, 3476 Mal_Interferon cells, 2277 Mal_Metabolism cells, 6478 Mal_Protein_related cells, and 3076 Mal_Stress cells (

Figure 2D). We also attempted to interpret the co-expression patterns of different gene modules at the single-cell level. The results showed strong and complex co-expression relationships between the stress, EMT, interferon, and protein-related modules, while the expression of the remaining three modules was relatively independent (

Figure 2E).

In summary, by using NMF, we identified seven gene modules that are widely present in HCC tumor cells, thoroughly explored their functions, and revealed their complex co-expression patterns. The expression of these modules provides a molecular basis for ITH.

3.3. Spatial Organization of HCC

To analyze the impact of ITH on the TME, we explored seven tumor ST samples from five HCC patients. After quality control, the ST dataset contained a total of 27,730 data spots (with an average of 3961 spots per sample and 3257 genes per spot) (

Supplementary Figure S3A,B). Since each spot represents a cell population, we used cell2location, based on annotated scRNA-seq data, to deconvolute each spot, thereby improving the resolution of cell type composition. We further explored whether the abundance of a specific cell type within a spot could predict the abundance of other cell types within that spot or its surrounding neighborhood. For this, we used the misty method to evaluate three different neighborhood areas: (1) the importance of cell type abundance within a single spot (co-localization), (2) in an immediate neighborhood with a radius of one spot, and (3) in an extended neighborhood that defined to a radius of 15 spots. The results show that, across the entire tumor area, the cell type abundance within a single tissue spot plays the most important role in predicting cell co-localization (

Supplementary Figure S3C).

Analysis across samples revealed that T cells, B cells, and NK cells could predict each other’s abundance within spots, indicating spatial proximity and shared distribution patterns. Among malignant cell types, Mal_Cell_cycle and Mal_Hypoxia (

p = 0.02) showed the strongest predictive relationship, suggesting that tumor proliferation may drive hypoxia. We also observed interdependencies between myeloid and mesenchymal cells (

p = 0.02), known for their role in building the HCC immune barrier [

28,

29,

30], and between mesenchymal and endothelial cells (

p = 0.01), reflecting mesenchymal cells’ involvement in tumor angiogenesis [

31] (

Figure 3A,B,

Supplementary Table S2). Correlation analysis of cell type abundance and misty results of immediate and extended neighborhoods confirmed these findings and validated the robustness of the results (

Figure 3C,

Supplementary Figure S3D,E, Supplementary Table S3).

We further explored co-localization relationships between signaling pathways (

Figure 3D,E,

Supplementary Table S2) and found that the MAPK and EGFR pathways were the strongest predictors of each other (

p = 0.007). This aligns with previous findings that EGFR activates Ras, which triggers the MAPK pathway to promote cell proliferation [

32]. Additionally, the JAK-STAT, TNFα, and NFκB pathways showed strong co-dependencies due to their shared roles in immune regulation [

33]. We also found a significant co-localization between the TGFβ and hypoxia pathways (

p = 0.007), consistent with reports that hypoxia stabilizes HIF-1α, promoting TGFβ activation [

34]. Correlation analysis of pathway abundance and misty results of immediate and extended neighborhoods confirmed these findings and validated the robustness of the results (

Figure 3F,

Supplementary Figure S3F,G, Supplementary Table S3).

To link tissue structure with function, we analyzed spatial dependencies between cell types and pathways (

Figure 3G). Mesenchymal cells showed strong co-localization with TGFβ and hypoxia pathways, indicating their activation. The JAK-STAT, TNFα, and NFκB pathways were activated in both immune cells and Mal_Interferon cells, suggesting Mal_Interferon’s involvement in immune responses. The VEGF pathway was activated in endothelial, myeloid, and Mal_Hypoxia cells, indicating their role in tumor angiogenesis. Correlation analysis of pathways and cell type and misty results of extended neighborhoods confirmed these findings and validated the robustness of the results. (

Figure 3H;

Supplementary Figure S3H). Visualizing cell type distribution in ST samples showed strong concordance with the misty results, further validating our findings (

Figure 3I–L).

In summary, misty analysis clarified co-localization relationships between cell types, pathways, and cell type–pathway interactions in HCC, revealing key intercellular interactions and their functional relevance within the TME.

3.4. Niche Identification in HCC

Co-localization analysis revealed specific dependencies between cell types, highlighting the importance of tumor spatial architecture in understanding tumor complexity. This led us to hypothesize the existence of distinct cell type niches within the HCC TME formed through cell interactions and performing specific functions. To characterize these niches, we applied ISCHIA, which reconstructs the local TME structure by analyzing spatial co-occurrence patterns and cell collaborations.

Through clustering analysis based on cell type composition, we identified eight compositional clusters (CCs), referred to as niches (

Figure 4C). Next, we investigated whether unique cell types were overexpressed in niches (

Figure 4A,B;

Supplementary Figure S4B,C). Immune cells, including T cells, NK cells, B cells, and plasma cells, were highly enriched in CC7, along with endothelial and myeloid cells, suggesting it is an immune-activated niche. CC5 contained Mal_Interferon, Mal_Cell_cycle, Myeloid cells, and Mal_EMT, while CC2 was primarily enriched with Mal_Hypoxia and Mal_Metabolism, indicating higher malignant cell content. CC1 and CC3 mainly contained Mal_Metabolism and Mal_Stress cells, whereas CC6 and CC8 were dominated by Mal_Protein_related cells. CC4, although its abundance may not vary across samples, exhibited a mixed composition of Mal_Protein_related and Mal_Interferon cells, suggesting that it may reflect a conserved biological feature within HCC.

Using MIA, we assessed whether certain cell types were enriched in specific regions (

Figure 4D;

Supplementary Table S1). Malignant cell genes were primarily enriched in CC2, CC3, CC4, CC6, and CC8, while immune and stromal cell genes were enriched in CC7 and CC1. Notably, CC5 showed enrichment of genes from malignant, immune, and stromal cells, suggesting it may serve as a transitional zone between malignant and benign cells, warranting further investigation.

Analysis of CC distribution across samples showed that all CCs, except for CC4, were present across different samples, indicating that these niches are widespread in the HCC TME (

Supplementary Figure S4A). Spatial visualization revealed that CC distribution closely aligns with HE staining patterns, consistent with previous findings [

35] (

Figure 4E;

Supplementary Figure S4D).

In conclusion, ISCHIA analysis identified eight distinct niches in the HCC TME, highlighting complex spatial patterns and interactions between cell types within these regions.

3.5. High-Resolution Spatial Co-Localization Reveals Complex Tumor Microenvironment Patterns and Hypoxia-Driven Angiogenesis

Previous analyses revealed strong co-localization among seven malignant cell types but weaker interactions with immune and stromal cells, contradicting our hypothesis that ITH drives TME differences. We attributed this to insufficient cell resolution and performed a refined misty analysis using 48 subpopulations of malignant, immune, and stromal cells, generating a high-resolution spatial map of the HCC TME (

Supplementary Figure S5).

The analysis showed that 17 T and B cell subtypes exhibited strong interdependencies and significant co-localization. Smooth muscle cells (Smc) and Arterial EC also displayed strong spatial associations due to their roles in vascular structure maintenance. Notably, we identified a cell community comprising SPP1+ Mac, VEGFA+ CAF, Mal_Interferon, Pericytes, LST1+ Mono, Neu, and S100A9+ Mono, with inter-predictive relationships among them. PLVAP+ EC, Mal_Cell cycle, Mal_Hypoxia, and Mal_EMT played key roles in predicting SPP1+ Mac and VEGFA+ CAF, indicating strong interdependencies. Co-localization was also observed between Mal_Cell cycle, Mal_Hypoxia, Mal_EMT, and Mal_Metabolism.

In previous studies, we demonstrated co-localization and cell communication between VEGFA

+ CAF and PLVAP

+ EC, suggesting their interaction drives tumor angiogenesis [

18]. Pathway analysis indicated that the top genes in VEGFA

+ CAF were hypoxia-related, implying that hypoxia promotes VEGFA

+ CAF transformation. Misty analysis confirmed that Mal_Hypoxia predicts PLVAP

+ EC and VEGFA

+ CAF presence (

Supplementary Figure S5). In the HCCT_5_3 sample, we observed similar distribution patterns, confirming their spatial association (

Figure 5A–C). SPATA2 identified two hypoxic regions, with Mal_Hypoxia abundance decreasing with distance from these regions (

Figure 5D–F). PLVAP

+ EC and VEGFA

+ CAF abundance followed similar trends, confirming their co-localization (

Figure 5G–J). Heatmap analysis further showed that PLVAP

+ EC and VEGFA

+ CAF levels decreased with distance from hypoxic regions, while immune cells like Activated B cells and CD5L

+ Mac increased (

Figure 5K,L). This pattern was consistent in the HCCT_5_2 sample, validating our findings (

Supplementary Figure S6A–L).

In conclusion, we generated a high-resolution co-localization map of cell types within HCC, revealing complex spatial patterns within the TME. Our findings highlighted the co-localization relationships between Mal_Hypoxia, PLVAP + EC, and VEGFA+ CAF, as well as their potential role in tumor angiogenesis.

3.6. Identification and Characteristic of Boundary Region

We identified a distinct niche, CC5, containing both malignant cells (e.g., Mal_Interferon and Mal_Cell_cycle) and immune cells (e.g., Myeloid_cells). MIA further showed that highly expressed genes in CC5 originate from malignant, immune, and stromal cells (

Figure 4D). Notably, CC5 is adjacent to CC7, a confirmed immune-infiltrated zone devoid of malignant cells. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that CC5 serves as a transitional boundary region between immune-infiltrated and tumor areas.

To validate this, we used Cottrazm, which integrates HE-stained images and scRNA-seq data to define tumor boundaries based on copy number variation. The tumor boundaries identified by Cottrazm overlapped well with the spatial boundaries of CC5, supporting our hypothesis (

Figure 6A–D,

Supplementary Figure S7A,B). We further employed Cytospace to map single cells to spatial profiles in the HCCT_5 sample, confirming that the immune region lacked malignant cells, while the boundary region included malignant, immune, and stromal cells (

Figure 6E,F,

Supplementary Figure S7C,D).

Ro/e analysis revealed distinct cell type distributions across regions: the boundary region was enriched in Lymphatic EC, DC1, CXCL10

+ Mac, SPP1

+ Mac, and Mal_Interferon; the immune region primarily contained CD8

+ Teff (effector T cell), CD8

+ Tm (memory T cell) et al., and stromal cells (e.g., MMP11

+ CAF, VEGFA

+ CAF); while the tumor region was predominantly enriched in Mal_Hypoxia, Mal_Cell_cycle, and Mal_Protein_related cells et al. (

Figure 6G).

To explore spatial gradients, we deployed a supervised spatial trajectory in the HCCT_5_1 slide, traversing the immune, boundary, and tumor regions (

Figure 6H,I). Along this axis, the abundance of Mal_Interferon, Mal_EMT, and SPP1

+ Mac increased, while immune cells (e.g., Plasma Naïve B cells) decreased (

Figure 6J,K,

Supplementary Figure S7E,F). A similar trend was observed in the HCCT_5_3 sample, further confirming these patterns (

Supplementary Figure S7G–L).

In summary, our findings suggest that CC5 functions as a transitional zone between the tumor and immune regions, exhibiting a distinct cellular composition and function, highlighting its potential role in tumor–immune interactions.

3.7. Boundary Region Complexity: Spatial Interactions Shaping the TME

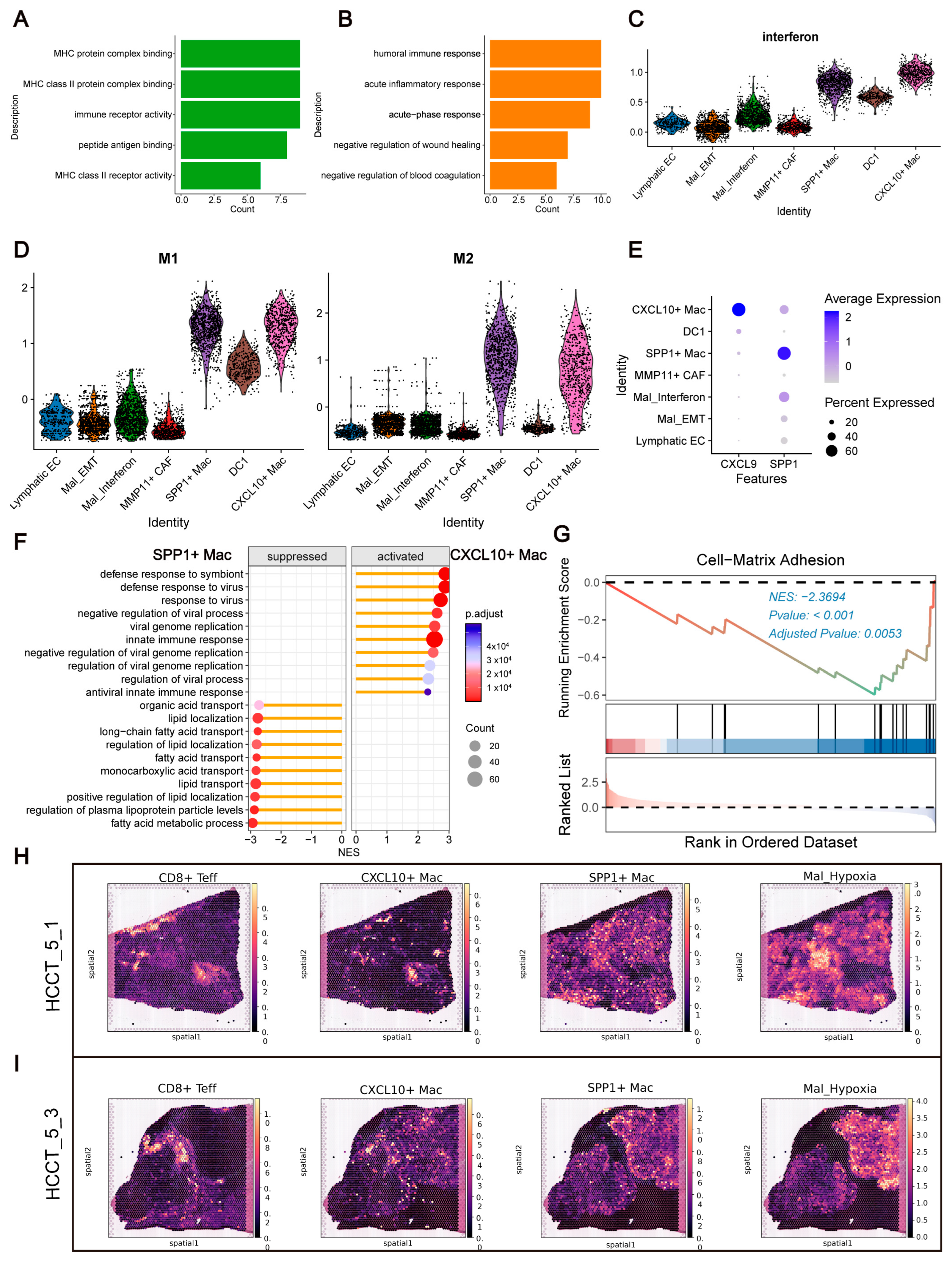

Based on the findings from previous analyses, we became particularly interested in the boundary region and conducted a more detailed analysis of the enriched cell types in this area. Enrichment analysis revealed that DC1 was primarily associated with antigen presentation pathways (e.g., MHC class II receptor activity), while Mal_Interferon was linked to immune-related pathways, including the humoral immune response (

Figure 7A,B). We calculated interferon scores for cell types in this region and found that Mal_Interferon had higher scores than other tumor cells, though lower than SPP1

+ Mac, DC1, and CXCL10

+ Mac (

Figure 7C). DNA fragments can not only activate the cGAS-STING pathway—promoting IFNα and IFNβ secretion in tumor cells—but also induce the activation of DC1 [

36]. We hypothesize that the boundary region may be enriched with substantial amounts of extracellular DNA, potentially leading to the activation of DC1 and Mal_Interferon.

Lymphatic EC enrichment analysis revealed terms related to leukocyte migration, suggesting a role in immune cell chemotaxis. CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac were enriched for cytokine-related and chemotaxis-related terms, respectively (

Supplementary Figure S8A–C). We then attempted to perform traditional M1/M2 macrophage scoring on CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac; surprisingly, both subpopulations exhibited similar scores for both M1 and M2 phenotypes (

Figure 7D), which is consistent with findings from previous studies [

37]. Studies have indicated that CXCL9 and SPP1 markers provide a better definition of macrophage polarization and are significantly correlated with patient prognosis [

37]. We examined the expression of CXCL9 and SPP1 in the CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac subpopulations and found that these markers more effectively distinguished the two subpopulations compared to traditional M1/M2 scores (

Figure 7E).

We performed differential gene expression analysis on CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac to investigate their functional differences. To ensure unbiased results, we conducted both ORA and GSEA analyses, yielding consistent findings (

Figure 7F,G;

Supplementary Figure S8D–F). CXCL10

+ Mac was primarily associated with innate immune responses and cytokine-related pathways, while SPP1

+ Mac was linked to lipid transport and metabolic processes. Additionally, we found that SPP1

+ Mac participates in cell–matrix adhesion, which may contribute to its role in maintaining the immune barrier. CXCL10

+ Mac expressed CXCL10 and CXCL9, while SPP1

+ Mac expressed SPP1, FABP4, and FABP5, which are fatty acid-binding proteins (

Supplementary Figure S8D). Previous studies have shown that FABP4 is highly expressed in adipocytes and macrophages, and that SPP1, FABP4, FABP5, and TREM2 expression in macrophages is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer [

38]. Additionally, FABP4-mediated activation of the NLRP3/IL-1β axis has been shown to regulate pancreatic cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis [

39].

Despite their distinct functions, both subtypes co-localized in the same regions, similar to findings in pancreatic cancer, where inflammatory FCN1

+ Mac and immunosuppressive SPP1

+/C1Q

+ Mac coexist, forming a complex immune ecosystem [

35]. We aimed to investigate whether the spatial distribution of the boundary region influences the differentiation of CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac. Although both macrophage subtypes were enriched in the boundary region, we found that CXCL10

+ Mac was primarily located closer to the immune region, while SPP1

+ Mac was closer to the tumor region (

Figure 7H,I;

Supplementary Figure S8G; Supplementary Figure S5). This finding aligns with the study by Ruben Bill et al., who found increased accumulations of CXCL9

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac at the interface between the tumor stroma and tumor nests, respectively, suggesting that spatial position may play a critical role in the differentiation of these macrophage subtypes. Moreover, their study found that regions near CXCL9

+ Mac were enriched with IFNG

+ T cells, the primary producers of IFNγ, whereas SPP1

+ Mac were found near GLUT1

+ cells, indicating a hypoxic environment. Similarly, our data showed that CXCL10

+ Mac had a strong spatial association with CD8

+ Teff cells, while SPP1

+ Mac co-localized with Mal_Hypoxia cells (

Figure 7H,I;

Supplementary Figure S8G). This suggests that ITH may create distinct TME that influence macrophage differentiation and function.

4. Discussion

ITH is a core cause of treatment failure, metastasis, and other cancer phenotypes, yet its spatial impact on the TME in HCC remains poorly understood. In this study, we integrated single-cell and spatial transcriptomic data to characterize seven malignant transcriptional programs and their mixed expression across tumors. By mapping these programs onto spatial landscapes, we identified eight distinct cellular niches with specific immune and stromal features. We further uncovered spatially organized interactions—such as a hypoxia–CAF–endothelium axis and functionally polarized macrophage subsets—highlighting how ITH shapes local tissue architecture and signaling. Together, these findings offer a spatially resolved framework for understanding tumor–microenvironment interplay in HCC.

We focused on how ITH influences the TME and impacts tumor biology and prognosis by examining co-localization relationships between tumor, immune, and stromal cells. Our previous work [

18] showed that VEGFA

+ CAF promote tumor angiogenesis through cellular communication with PLVAP

+ EC. Enrichment analysis revealed that VEGFA

+ CAF are primarily linked to hypoxia-related pathways, suggesting that hypoxia may drive VEGFA

+ CAF transformation. We confirmed the spatial co-localization of Mal_Hypoxia, VEGFA

+ CAF, and PLVAP

+ EC, proposing that Mal_Hypoxia promotes VEGFA

+ CAF transformation and PLVAP

+ EC proliferation, thereby facilitating angiogenesis. While the role of hypoxia in tumor angiogenesis is well established, our study emphasizes that spatial co-localization and cellular communication between these cell types are critical to this process. Notably, we also observed that IGF2—a well-known hypoxia-inducible, pro-angiogenic factor—was predominantly expressed in Mal_Hypoxia tumor cells (

Supplementary Figure S9). Although its role was not the primary focus of this study, IGF2 may contribute to the hypoxia-driven VEGFA

+ CAF and PLVAP

+ EC axis and represents a promising target for future mechanistic validation.

We identified a unique compositional cluster (CC5), enriched with tumor cells, immune cells, and stromal cells, located between the immune-infiltrated region and the tumor region, which served as a transitional zone between the tumor region and the immune-infiltrated region. Early studies exploring the role of cGAS–STING-mediated immunity in cancer highlighted the critical function of DNA-dependent DC activation as a key event driving type I interferon (IFN) production and CD8

+ T cell priming [

40]. Cell death, a ubiquitous phenomenon during tumor progression, results in the release of DNA from dying tumor cells and other components of the tumor TME. This extracellular DNA, upon internalization by phagocytes, has been proposed to serve as a potent trigger for cGAS activation [

41]. We believe that the enrichment of DC1 and Mal_Interferon in the boundary region is not coincidental but likely linked to proximity to the immune region. DNA may be released during tumor cell apoptosis, potentially triggered by antibodies produced by infiltrating plasma cells in the adjacent immune-rich zone, thereby further activating macrophage- or NK cell-dependent apoptosis [

42].

In the boundary region, we also observed the enrichment of CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac. Interestingly, traditional M1/M2 macrophage scoring did not effectively distinguish these two subpopulations, but their unique functions could be identified through the high expression of CXCL9 and SPP1. Functional enrichment analysis showed that CXCL10

+ Mac is mainly associated with innate immune responses and cytokine activity, while SPP1

+ Mac is enriched in lipid metabolism and transport functions. Zhou Liu et al. identified macrophages expressing SPP1, FABP4, and TREM2 in breast cancer and found that these cells were primarily distributed in the tumor stroma region and associated with poor prognosis [

38].Additionally, FABP4-mediated activation of the NLRP3/IL-1β axis has been shown to regulate pancreatic cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis [

39].

Although located within the same region, CXCL10

+ Mac and SPP1

+ Mac exhibited subtle spatial positioning differences, which may underlie their distinct functional characteristics. CXCL10

+ Mac was predominantly located adjacent to the immune-infiltrated region, while SPP1

+ Mac was found near the tumor region. Research has shown that the proximity between CXCL9

+ Mac and CXCR3

+ IFNG

+ T cells can promote the acquisition of a CXCL9 phenotype, whereas hypoxia promotes the acquisition of the SPP1

+ phenotype [

39], which aligns with our observations. CXCL10

+ Mac exhibits robust immune-related functions; however, in the boundary region, Mal_Hypoxia may reshape it into an immunosuppressive SPP1

+ Mac phenotype. SPP1

+ Mac cells likely serve a dual role, acting as both an immune barrier and a promoter of tumor cell proliferation, thereby protecting the tumor. This phenomenon reminds us of the activation and exhaustion of CD8

+ T cells, further underscoring the critical role of the interplay between ITH and the tumor TME in shaping the TME and establishing unique spatial architectures.

Cancer cells are remarkably “intelligent” and highly adaptable. They not only leverage their heterogeneity to achieve immune evasion and promote angiogenesis but also collaborate with immune and stromal cells to form specific spatial niches. We propose that cancer characteristics need not be defined solely by the assembly of all individual cells. Instead, cell states may be enhanced by cellular cooperation within the tumor ecosystem, increasing the tumor’s overall adaptability. In this process, cell-to-cell signaling, the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients, and the distribution of cells across different spatial niches all critically influence the tumor’s collective behavior and evolution. Therefore, gaining an in-depth understanding of the spatial structure within tumors and the cooperative relationships among cells is essential for revealing the fundamental mechanisms of tumor function and for exploring potential therapeutic strategies.

This study has several limitations. First, the spatial transcriptomic data were derived from a limited number of samples (seven slides from five HCC patients), which may restrict the generalizability of our findings. Second, key spatial features and mechanistic hypotheses were inferred from transcriptomic patterns without direct experimental or histopathological validation, and the absence of matched clinical information limited our ability to link spatial architectures to patient outcomes, thereby reducing translational relevance. Third, while core analyses were internally cross-validated, certain modeling components lacked rigorous statistical controls such as global multiple testing correction, warranting cautious interpretation and future methodological refinement.