Defining Gene Signature of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma as Target for Immunotherapy Using Single Cell and Bulk RNA Sequencing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Tissue Specimens

2.2. Single-Cell RNA-seq Quality Control and Data Processing

2.3. Analysis of Macrophage Clusters

2.4. Identification of Unique Gene Markers in Macrophage Subpopulations

2.5. Bulk RNA-seq Analysis

2.6. Corroboration of scRNA-seq and Bulk RNA-seq Data

2.7. CIBERSORT Analysis

2.8. STRING Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Characterization of Macrophage Subpopulations by scRNA-seq Data

3.3. TAM Population Is Characterized by Expression of TREM2, CD9 and PRMT10

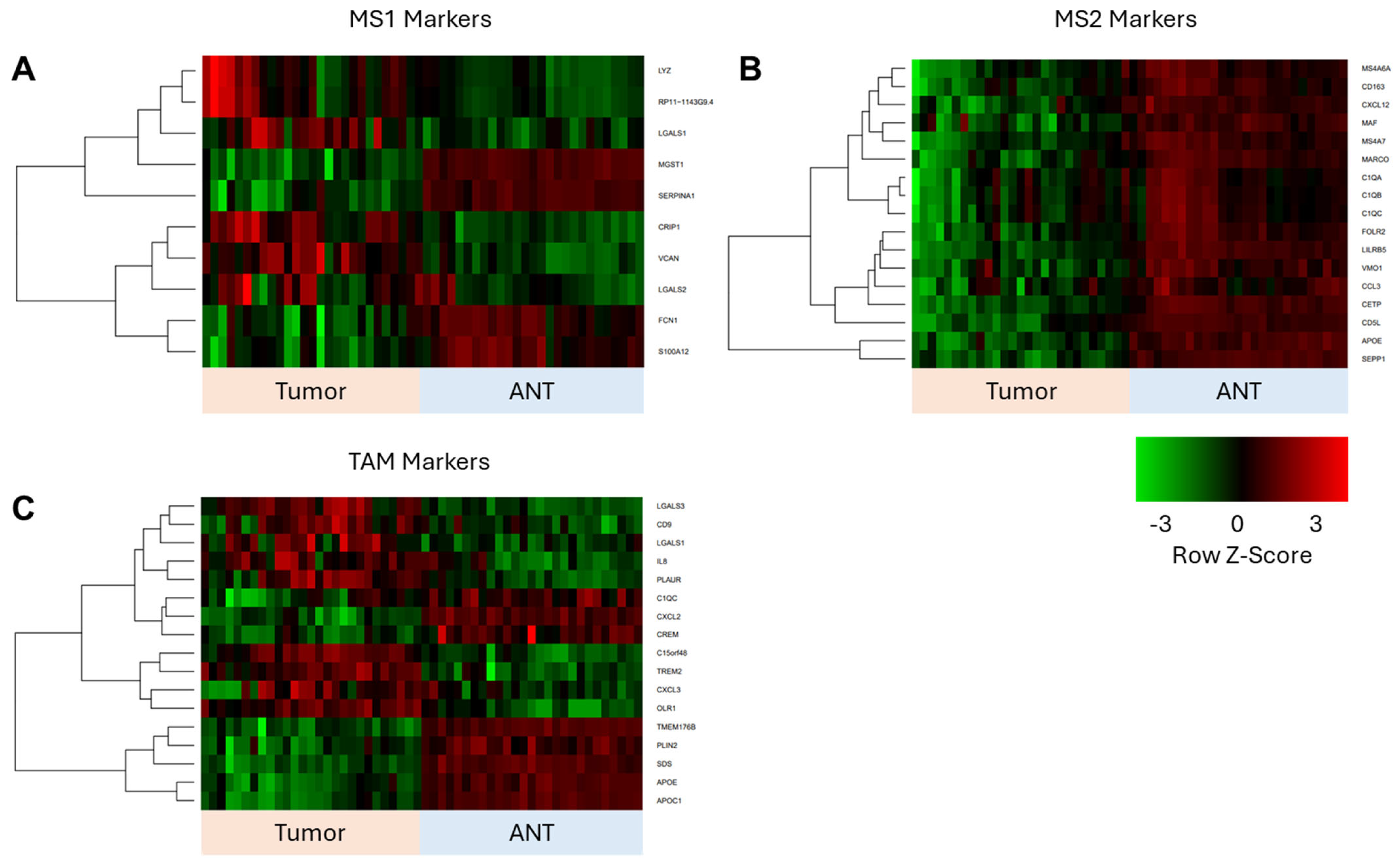

3.4. Corroboration of scRNAseq Data with Bulk RNAseq Data from ICC Validation Cohort

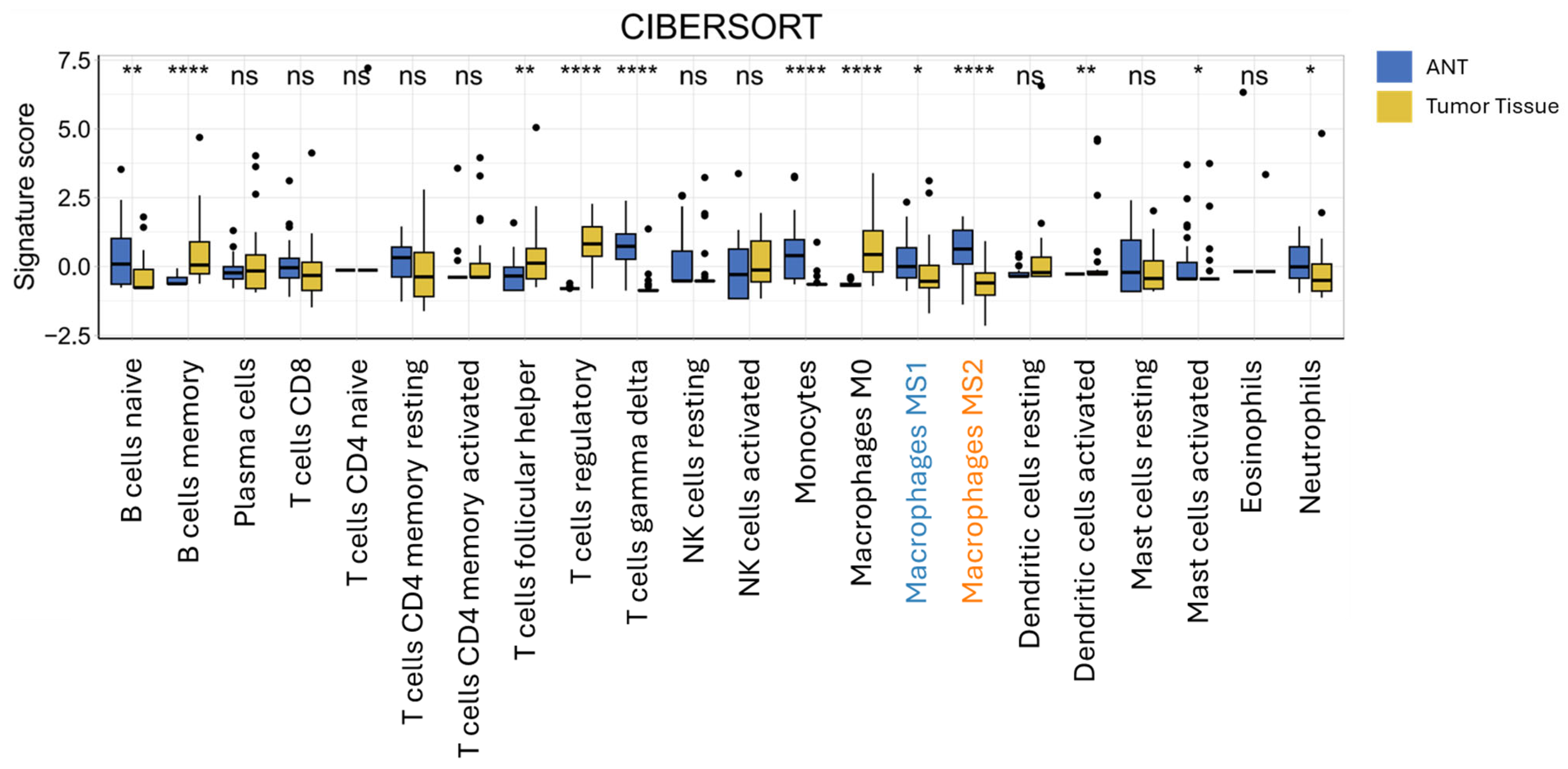

3.5. CIBERSORT Immune Cell Deconvolution of Bulk RNAseq Data from ICC and Adjacent Non-Tumorous Tissue

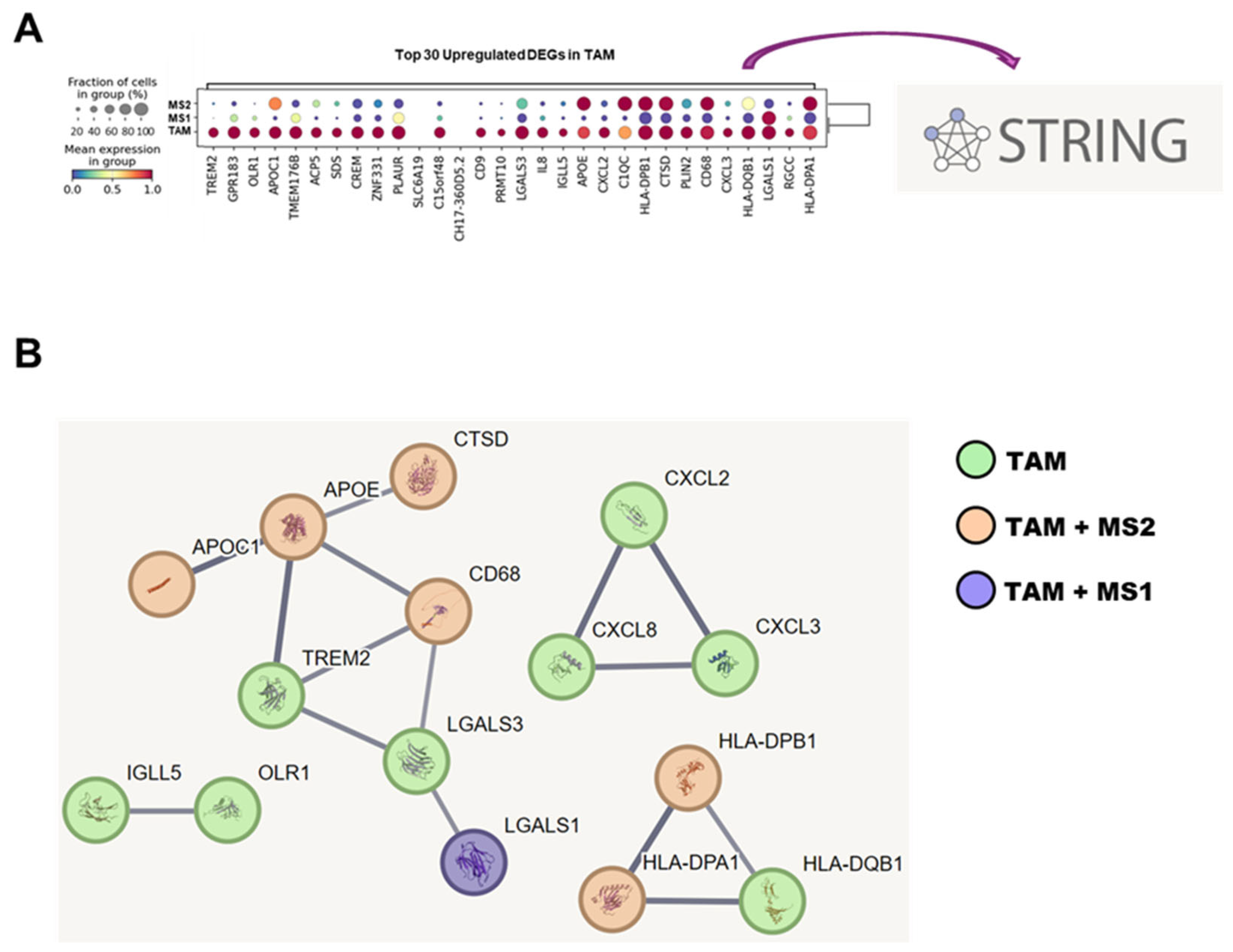

3.6. STRING Database Analysis of TAM-Associated Genes in Network of Protein–Protein Interactions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANT | adjacent non-tumorous tissue |

| APOC1 | apolipoprotein C1 |

| APOE | apolipoprotein E |

| C1QA | complement C1q A chain |

| C1QB | complement C1q B chain |

| C1QC | complement C1q C chain |

| CD5L | CD5 antigen-like |

| CETP | cholesteryl ester transfer protein |

| CLEC10A | C-type lectin domain family 10 member A |

| CSTA | cystatin A |

| CTSB | cathepsin B |

| CTSD | cathepsin D |

| CXCL2 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 |

| CXCL3 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 3 |

| CXCL8 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 8 |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| FCN1 | ficolin 1 |

| GEO | gene expression omnibus |

| HBV+ | hepatitis B positive |

| HLA-DPA1 | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DP alpha 1 |

| HLA-DPB1 | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DP beta 1 |

| HLA-DQB1 | major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ beta 1 |

| ICC | intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma |

| IGLL5 | immunoglobulin lambda like polypeptide 5 |

| IOBR | immuno-oncology biological research |

| LGALS1 | galectin-1 |

| LGALS3 | galectin-3 |

| LILRB5 | leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor subfamily B member 5 |

| LYZ | lysozyme |

| MARCO | macrophage receptor with collagenous structure |

| MDSCs | myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MS | macrophage subpopulations |

| MS1 | inflammatory macrophages |

| MS2 | anti-inflammatory macrophages |

| NK | natural killer |

| OLR1 | oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1 |

| OS | overall survival |

| PPI | protein–protein interaction |

| PRMT10 | protein arginine methyltransferase 10 |

| S100A8 | S100 calcium-binding protein A8 |

| S100A12 | S100 calcium-binding protein A12 |

| ScRNA-seq | single-cell rna sequencing |

| SEPP1 | selenoprotein P, plasma, 1 |

| TAM | tumor-associated macrophages |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TPM | transcripts per million |

| T reg | regulatory T-cells |

| TREM2 | triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

| UMAP | uniform manifold approximation and projection |

| VCAM1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

References

- Olthof, P.B.; Franssen, S.; van Keulen, A.-M.; van der Geest, L.G.; Hoogwater, F.J.; Coenraad, M.; van Driel, L.M.; Erdmann, J.I.; Mohammad, N.H.; Heij, L.; et al. Nationwide treatment and outcomes of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. HPB 2023, 25, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, C.; Lu, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Ma, Y. Tumor-associated macrophages in cholangiocarcinoma: Complex interplay and potential therapeutic target. EBioMedicine 2021, 67, 103375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K.; Zhu, A.X.; Fuchs, C.S.; Brooks, G.A. Forty-Year Trends in Cholangiocarcinoma Incidence in the U.S.: Intrahepatic Disease on the Rise. Oncologist 2016, 21, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tataru, D.; Khan, S.A.; Hill, R.; Morement, H.; Wong, K.; Paley, L.; Toledano, M.B. Cholangiocarcinoma across England: Temporal changes in incidence, survival and routes to diagnosis by region and level of socioeconomic deprivation. JHEP Rep. 2024, 6, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greten, T.F.; Schwabe, R.; Bardeesy, N.; Ma, L.; Goyal, L.; Kelley, R.K.; Wang, X.W. Immunology and immunotherapy of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, M.J.; Michielin, O.; Migliorini, D. Clinical relevance of tumour-associated macrophages. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Sheng, J.; Li, X.; Gao, Z.; Hu, L.; Chen, M.; Fei, J.; Song, Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: Orchestrators of cholangiocarcinoma progression. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1451474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Alexander, P. Cooperation of immune lymphoid cells with macrophages in tumour immunity. Nature 1970, 228, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wan, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Ge, C.; Liu, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, G.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic architecture and intercellular crosstalk of human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.; Dobie, R.; Wilson-Kanamori, J.R.; Dora, E.F.; Henderson, B.E.P.; Luu, N.T.; Portman, J.R.; Matchett, K.P.; Brice, M.; Marwick, J.A.; et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature 2019, 575, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.S.; O’bRien, D.; Na Kang, Y.; Mounajjed, T.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, T.-S.; Kocher, J.-P.A.; Allotey, L.K.; Borad, M.J.; Roberts, L.R.; et al. Prognostic subclass of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by integrative molecular-clinical analysis and potential targeted approach. Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.A.; Angerer, P.; Theis, F.J. SCANPY: Large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polański, K.; Young, M.D.; Miao, Z.; Meyer, K.B.; A Teichmann, S.; Park, J.-E. BBKNN: Fast batch alignment of single cell transcriptomes. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 964–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traag, V.A.; Waltman, L.; Van Eck, N.J. From Louvain to Leiden: Guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, G.; Jiang, A.Y.; Lynch, A.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Kang, J.; Gu, S.S.; et al. MetaTiME integrates single-cell gene expression to characterize the meta-components of the tumor immune microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotto, L.; Cole, B.; Giese, W.; Baumann, E.; Claeys, A.; Vanmechelen, M.; Decraene, B.; Derweduwe, M.; Lakic, N.D.; Shankar, G.; et al. Single-cell profiling and zebrafish avatars reveal LGALS1 as immunomodulating target in glioblastoma. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e18144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Qian, J.; Ding, L.; Yin, S.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S. Galectin-1: A Traditionally Immunosuppressive Protein Displays Context-Dependent Capacities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information NCfB. NCBI Gene Datasets: NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/gene/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J. Strategies for treating the cold tumors of cholangiocarcinoma: Core concepts and future directions. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 24, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Liu, X.; Peng, H.; Peng, Z.-W.; Long, J.-T.; Tang, D.; Peng, S.; Bao, Y.; Kuang, M. Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy and Radiotherapy for Stage IV Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Case Report. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerneur, C.; Cano, C.E.; Olive, D. Major pathways involved in macrophage polarization in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1026954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.Y.; Cho, S.W.; A Kim, Y.; Kim, D.; Oh, B.-C.; Park, D.J.; Park, Y.J. Cancers with Higher Density of Tumor-Associated Macrophages Were Associated with Poor Survival Rates. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 2015, 49, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liao, S.; Zhao, X.; Ning, Q.; Tang, S. Mechanisms of tumor-associated macrophages promoting tumor immune escape. Carcinogenesis 2025, 46, bgaf023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossel, D.M.; Moganti, K.; Riabov, V.; Weiss, C.; Kopf, S.; Cordero, J.; Dobreva, G.; Rots, M.G.; Klüter, H.; Harmsen, M.C.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of S100A9 and S100A12 Expression in Monocyte-Macrophage System in Hyperglycemic Conditions. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Wei, W.; Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, H.; He, W.; Xia, J.; Li, B.; et al. S100A12 is involved in the pathology of osteoarthritis by promoting M1 macrophage polarization via the NF-κB pathway. Connect. Tissue Res. 2024, 65, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira-Junior, R.; Holmström, S.B.; Clark, R.; Zwicker, S.; Majster, M.; Johannsen, G.; Axtelius, B.; Åkerman, S.; Svensson, M.; Klinge, B.; et al. S100A12 Expression Is Modulated During Monocyte Differentiation and Reflects Periodontitis Severity. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Wang, L.; Dong, Q.; Xu, K.; Ye, J.; Shao, X.; Yang, S.; Lu, C.; Chang, C.; Hou, Y.; et al. Aberrant LYZ expression in tumor cells serves as the potential biomarker and target for HCC and promotes tumor progression via csGRP78. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2215744120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudjord-Levann, A.M.; Ye, Z.; Hafkenscheid, L.; Horn, S.; Wiegertjes, R.; Nielsen, M.A.; Song, M.; Mathiesen, C.B.; Stoop, J.; Stowell, S.; et al. Galectin-1 induces a tumor-associated macrophage phenotype and upregulates indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1. iScience 2023, 26, 106984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.; Silva, M.C.; Gomes, A.P.; Santos, R.F.; Cardoso, M.S.; Nóvoa, A.; Luche, H.; Cavadas, B.; Amorim, I.; Gärtner, F.; et al. CD5L as a promising biological therapeutic for treating sepsis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjurjo, L.; Aran, G.; Téllez, É.; Amézaga, N.; Armengol, C.; López, D.; Prats, C.; Sarrias, M.-R. CD5L Promotes M2 Macrophage Polarization through Autophagy-Mediated Upregulation of ID3. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambier, S.; Gouwy, M.; Proost, P. The chemokines CXCL8 and CXCL12: Molecular and functional properties, role in disease and efforts towards pharmacological intervention. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 217–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Lou, C.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Long, S.; Wang, Y.; Shang, Z.; et al. CXCL12 derived from CD248-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts mediates M2-polarized macrophages to promote nonsmall cell lung cancer progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Yi, C.; Pan, W.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Duan, Y.; Ning, X.; Li, J.; et al. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) contributes to macular fibrosis in neovascular age-related macular degeneration through modulating macrophage functions. Immun. Ageing 2023, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, F.; Coindre, S.; Gardet, M.; Meurisse, F.; Naji, A.; Suganuma, N.; Abi-Rached, L.; Lambotte, O.; Favier, B. Leukocyte Immunoglobulin-Like Receptors in Regulating the Immune Response in Infectious Diseases: A Window of Opportunity to Pathogen Persistence and a Sound Target in Therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 717998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorighello, G.G.; Assis, L.H.P.; Rentz, T.; Morari, J.; Santana, M.F.M.; Passarelli, M.; Ridgway, N.D.; Vercesi, A.E.; Oliveira, H.C.F. Novel Role of CETP in Macrophages: Reduction of Mitochondrial Oxidants Production and Modulation of Cell Immune-Metabolic Profile. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.D.; Gao, J.; Tang, A.F.; Feng, C. Shaping the immune landscape: Multidimensional environmental stimuli refine macrophage polarization and foster revolutionary approaches in tissue regeneration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, H.; Butenko, S.; Polishuk-Zotkin, I.; Schif-Zuck, S.; Pérez-Sáez, J.M.; Rabinovich, G.A.; Ariel, A. Galectin-1 Facilitates Macrophage Reprogramming and Resolution of Inflammation Through IFN-β. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J. TREM2 marks tumor-associated macrophages. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, M.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Fridman, W.H.; Roumenina, L.T. C1q+ macrophages: Passengers or drivers of cancer progression. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, W.; Wang, H.; Xiang, X.; Ye, L.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Xue, Q.; Chen, L.; Su, Y.; et al. C1q+ tumor-associated macro-phages contribute to immunosuppression through fatty acid metabolic reprogramming in malignant pleural effusion. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vidergar, R.; Biswas, S.K. Metabolic regulation of Cathepsin B in tumor macrophages drives their pro-metastatic function. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, M.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S. The Role of Cathepsin B in Pathophysiologies of Non-tumor and Tumor tissues: A Systematic Review. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 2344–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, B.; Kiss, R.S.; Sarov-Blat, L.; Brunet, R.; Harder, C.; McPherson, R.; Marcel, Y.L. Cathepsin D, a lysosomal protease, regulates ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 39971–39981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Woo, S.M.; Seo, S.U.; Lee, C.-H.; Baek, M.-C.; Jang, S.H.; Park, Z.Y.; Yook, S.; Nam, J.-O.; Kwon, T.K. Cathepsin D promotes polarization of tumor-associated macrophages and metastasis through TGFBI-CCL20 signaling. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Luo, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages-derived exosomes promote the migration of gastric cancer cells by transfer of functional Apolipoprotein E. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Zhao, R.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Bin, Y.; Wang, D.; Xue, G.; Wu, J.; Lin, X. APOE expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma: Influencing tumor progression and macrophage polarization. Immunobiology 2024, 229, 152821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yi, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, B.; et al. Systematic pan-cancer analysis identifies APOC1 as an immunological biomarker which regulates macrophage polarization and promotes tumor metastasis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 183, 106376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Liu, F.; Yang, K. Role of CD68 in tumor immunity and prognosis prediction in pan-cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Miao, Y.; Zhong, L.; Feng, S.; Xu, Y.; Tang, L.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Gu, L.; Diao, H.; et al. Identification of TREM2-positive tumor-associated macrophages in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Implication for poor prognosis and immunotherapy modulation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1162032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, L.; Yao, J.; Wang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, S.; Zhang, D.; Deng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Overexpressed Pseudogene. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-C.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chang, Y.-F.; Yeh, C.-C.; Su, C.-T.; Wu, J.-S.; Su, F.-H. Association of HLA-DPA1, HLA-DPB1, and HLA-DQB1 Alleles with the Long-Term and Booster Immune Responses of Young Adults Vaccinated Against the Hepatitis B Virus as Neonates. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 710414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Tian, Y.; Lv, C. Decoding the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of tumor-associated macrophages. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piollet, M.; Porsch, F.; Rizzo, G.; Kapser, F.; Schulz, D.J.J.; Kiss, M.G.; Schlepckow, K.; Morenas-Rodriguez, E.; Sen, M.O.; Gropper, J.; et al. TREM2 protects from atherosclerosis by limiting necrotic core formation. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 3, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, M.; Guo, H.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, L. Integrated Analysis Highlights the Immunosuppressive Role of TREM2. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 848367. [Google Scholar]

- Adawy, A.; Komohara, Y.; Hibi, T. Tumor-associated macrophages: The key player in hepatoblastoma microenvironment and the promising therapeutic target. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 68, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, I.; Kazakova, E.; Patysheva, M.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Transcriptional, Epigenetic and Metabolic Programming of Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Cancers 2020, 12, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khantakova, D.; Brioschi, S.; Molgora, M. Exploring the Impact of TREM2 in Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Vaccines 2022, 10, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.-M.; Yang, Y.-Z.; Zhang, T.-Z.; Qin, C.-F.; Li, X.-N. LGALS3 Is a Poor Prognostic Factor in Diffusely Infiltrating Gliomas and Is Closely Correlated with CD163+ Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshoff, M.M.; Gupta, P.; Oberai, S.; Trivedi, R.; Katayama, H.; Chakrapani, P.; Dang, M.; Migliozzi, S.; Gumin, J.; Kadri, D.B.; et al. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) regulates phagocytosis in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2024, 26, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarella, F.; Filipello, F.; Bollman, B.; Cantoni, C.; Locca, A.; Mikesell, R.; Manis, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Deng, L.; Benitez, B.A.; et al. TREM2 activation on microglia promotes myelin debris clearance and remyelination in a model of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 140, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, T.; Jiang, G.; Zeng, Q.; Li, Z.; Huang, X. Target delivery of a PD-1-TREM2 scFv by CAR-T cells enhances anti-tumor efficacy in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Huang, X. Galectin-3 induces pathogenic immunosuppressive macrophages through interaction with TREM2 in lung cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosseau, C.; Colas, L.; Magnan, A.; Brouard, S. CD9 Tetraspanin: A New Pathway for the Regulation of Inflammation? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.W.; Cho, Y.; Bae, G.U.; Kim, S.N.; Kim, Y.K. Protein arginine methyltransferases: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 788–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.Y.; Black, A.; Qian, B.Z. Macrophage diversity in cancer revisited in the era of single-cell omics. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43, 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Dataset (GEO GSE138709) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient ID | Sex | Tumor Grade | TNM staging | Virus Infection | Pathology | Sample GEO ID |

| 18 | F | Poorly differentiated, Grade III | T3N1MX | HBV+ | ICC tumor | GSM4116580 |

| 20 | F | Moderately differentiated, Grade II | T2NXMX | -- | ICC tumor | GSM4116581 |

| 23 | M | Poorly differentiated, Grade III | T2NXMX | HBV+ | ICC tumor | GSM4116583 |

| 24_1 * | M | Moderately differentiated, Grade II | T2N0M0 | -- | ICC tumor | GSM4116584 |

| 24_2 * | M | Moderately differentiated, Grade II | T2N0M0 | -- | ICC tumor | GSM4116585 |

| 18 | F | Poorly differentiated, Grade III | T3N1MX | HBV+ | ICC adjacent | GSM4116579 |

| 23 | M | Poorly differentiated, Grade III | T2NXMX | HBV+ | ICC adjacent | GSM4116582 |

| 25 | M | Poorly differentiated, Grade III | T4N1M0 | -- | ICC adjacent | GSM4116586 |

| Healthy Liver Dataset (GEO GSE136103) | ||||||

| Healthy1_Cd45+ | M | -- | -- | -- | Normal liver | GSM4041150 |

| Healthy1_Cd45-A | GSM4041151 | |||||

| Healthy1_Cd45-B | GSM4041152 | |||||

| Healthy2_Cd45+ | M | -- | -- | -- | Normal liver | GSM4041153 |

| Healthy2_Cd45- | GSM4041154 | |||||

| Healthy3_Cd45+ | M | -- | -- | -- | Normal liver | GSM4041155 |

| Healthy3_Cd45-A | GSM4041156 | |||||

| Healthy3_Cd45-B | GSM4041157 | |||||

| Healthy4_Cd45+ | F | -- | -- | -- | Normal liver | GSM4041158 |

| Healthy4_Cd45- | GSM4041159 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badshah, J.S.; Lee, R.M.; Reitsma, A.; Melcher, M.L.; Martinez, O.M.; Krams, S.M.; Delitto, D.J.; Kirchner, V.A. Defining Gene Signature of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma as Target for Immunotherapy Using Single Cell and Bulk RNA Sequencing. Livers 2025, 5, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040053

Badshah JS, Lee RM, Reitsma A, Melcher ML, Martinez OM, Krams SM, Delitto DJ, Kirchner VA. Defining Gene Signature of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma as Target for Immunotherapy Using Single Cell and Bulk RNA Sequencing. Livers. 2025; 5(4):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040053

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadshah, Joshua S., Ryan M. Lee, Andrea Reitsma, Marc L. Melcher, Olivia M. Martinez, Sheri M. Krams, Daniel J. Delitto, and Varvara A. Kirchner. 2025. "Defining Gene Signature of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma as Target for Immunotherapy Using Single Cell and Bulk RNA Sequencing" Livers 5, no. 4: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040053

APA StyleBadshah, J. S., Lee, R. M., Reitsma, A., Melcher, M. L., Martinez, O. M., Krams, S. M., Delitto, D. J., & Kirchner, V. A. (2025). Defining Gene Signature of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma as Target for Immunotherapy Using Single Cell and Bulk RNA Sequencing. Livers, 5(4), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5040053