2.2. Data Collection and Variables

Data were extracted from electronic medical records after approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the São Paulo Municipal Health Secretariat (SMS/SP) (CAAE 83783024.3.0000.0086). After collection, the data were stored in an encrypted system accessible only to the research team authorized by the ethics committee and bound by confidentiality agreements, ensuring standardization, anonymity, and protection of personal information. Each participant was identified using an automatic, non-sequential alphanumeric code, with no possibility of personal identification. Sensitive information and personal identifiers were removed.

Women aged 18 years or older who underwent elective hysterectomy during the study period were eligible. Exclusion criteria included oncologic cases, urgent or emergency procedures, such as puerperal hysterectomies or surgeries for acute hemorrhage, and incomplete clinical records.

Incomplete data were handled using a complete-case analysis approach, with inclusion limited to patients with available information for all required variables. Records lacking the dates necessary to calculate waiting time or insufficient information to compute the clinical score were excluded a priori. No imputation of missing data was performed, as missingness was primarily attributable to documentation failures in medical records rather than a demonstrable random mechanism.

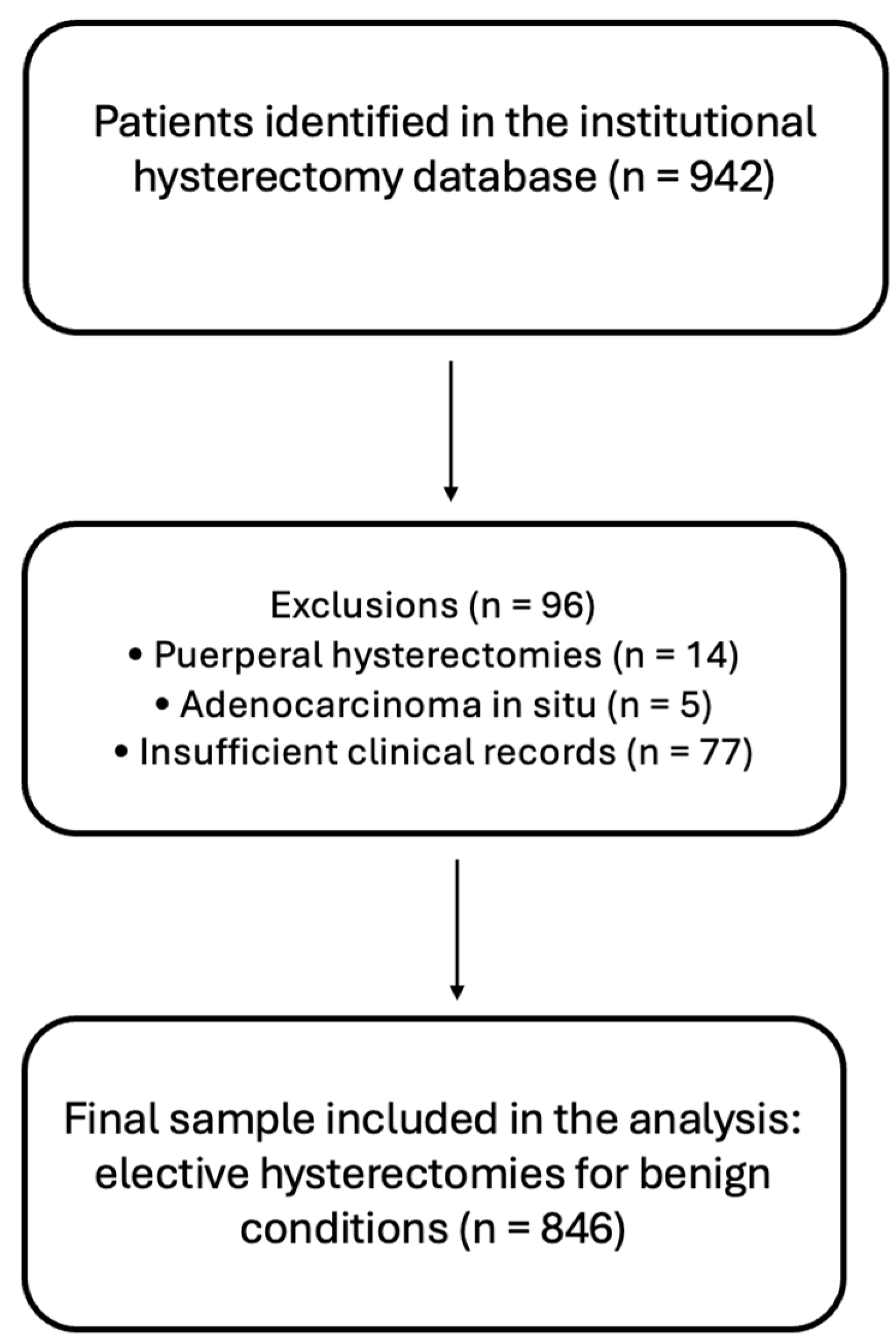

A total of 942 patients who underwent hysterectomy at the hospital during the study period were identified. Of these, 14 were excluded because they were puerperal hysterectomies, classified as emergency procedures, and 5 were excluded due to a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in situ, as they did not fall within the scope of benign disease and elective surgery. Additionally, 77 patients were excluded because of insufficient clinical records for application of the clinical score and/or calculation of surgical waiting time. The final sample comprised 846 women who underwent elective hysterectomy for benign conditions (

Figure 1).

The exclusion of patients with incomplete records may have introduced selection bias if missing information was associated with clinical severity or access barriers. In addition, waiting time depends on the accuracy of dates recorded in electronic medical records, and information bias may have occurred due to documentation inconsistencies. Finally, because the database did not include socioeconomic variables or race/ethnicity, it was not possible to adjust for relevant social determinants, raising the possibility of residual confounding in the interpretation of the observed associations.

The analyzed variables were grouped into five analytical domains:

Demographic and obstetric characteristics;

Clinical profile and comorbidities;

Laboratory parameters and complementary examinations;

Gynecologic and surgical factors;

Temporal indicators of the care trajectory.

Variables included age, reproductive history, comorbidities, medication use, laboratory results, underlying diagnosis, uterine volume, surgical approach and type of hysterectomy, as well as time intervals between symptom onset, diagnosis, surgical indication, and procedure performance. Surgical waiting time was defined as the interval, in months, between the date of surgical indication (as recorded in the electronic medical record), considered the starting point of the regulatory process for elective hysterectomy, and the date the surgery was performed. The choice of this starting point was based on the fact that surgical indication represents the first formal moment at which the patient becomes eligible for inclusion on a regulatory waiting list and at which clinical prioritization criteria should, in principle, influence surgical scheduling. The interval was calculated using the dates recorded in the electronic medical record and converted into months.

2.4. Risk Stratification Scoring System

This study aimed to adapt the Gyn-MeNTS score (

Table 1) to the context of the Brazilian public health system, creating an objective tool for prioritizing patients on the waiting list for elective hysterectomy.

Adaptation of the score was necessary due to substantial differences between the healthcare systems of the United States and Brazil, particularly with respect to hospital infrastructure, resource availability, epidemiological profiles, and anesthetic risk. To address these disparities, the score was modified to incorporate variables that better reflect the realities of the SUS, increasing its sensitivity, feasibility, and applicability within the national public system, while promoting more equitable and efficient allocation of surgical resources.

The adaptation of the Gyn-MeNTS score to the SUS context was conducted through a modified Delphi process aimed at achieving structured consensus among experts regarding the selection, categorization, and weighting of clinical variables. The Delphi panel comprised five senior gynecologic surgeons, all with more than 15 years of clinical and surgical experience in benign gynecology and direct involvement in surgical care and health regulation within the public health system.

The process was carried out in three iterative rounds. In the first round, experts independently evaluated a preliminary list of candidate variables derived from the original Gyn-MeNTS score and from clinical factors commonly documented in the hospital’s electronic medical records. In total, 12 candidate items were analyzed, encompassing clinical severity, comorbidities, and temporal indicators. Each item was scored using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not relevant; 5 = essential), based on three predefined criteria: clinical relevance, feasibility of extraction from medical records, and potential impact on promoting equity in surgical access.

Items that achieved ≥70% agreement, defined as a score of 4 or 5 assigned by at least 70% of the experts, were provisionally retained. Items that failed to reach consensus were excluded or reformulated based on the qualitative feedback provided by the participants.

In the second round, a refined list containing nine items was redistributed to the experts, incorporating the revisions suggested in the previous stage. At this phase, participants reassessed the retained variables, as well as the proposed categories and severity thresholds. The consensus criterion remained set at greater than 70% agreement. One variable related to operative complexity was excluded during this round due to low practical feasibility and inconsistent documentation within the SUS context.

The third and final round focused on final adjustments to variable definitions, score weighting, and cutoff points for surgical priority classification. Experts reviewed the near-final version of the score, which at that stage comprised eight clinical domains, and formally confirmed their agreement or provided final recommendations. In this round, consensus exceeded 80% agreement for all included variables, with no further inclusion or exclusion of items.

No relevant disagreements persisted after the third round. The final adapted score reflects convergence among clinical relevance, data availability, and applicability to surgical waiting-list management in the public sector. This modified Delphi process ensured methodological transparency, minimized individual bias, and strengthened the content validity of the proposed prioritization instrument.

The final model included eight clinical domains: pelvic pain and/or abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), anemia, age, pulmonary disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and duration of symptoms prior to surgery, all graded according to severity. The variable “time from symptom onset to surgery,” which was not included in the original score, was incorporated and categorized as <6 months, 6–12 months, and >12 months. In addition, the variable “pain,” originally present in the base model, was combined with the AUB criterion to form the composite item “pain and/or AUB,” categorized into three levels: asymptomatic, symptomatic without prior treatment, and symptomatic with symptoms refractory to treatment.

For the anemia criterion, cutoff points were defined in accordance with restrictive transfusion strategies (hemoglobin ≤ 6.5 g/dL or recent transfusion indicating greater severity; 6.6–10 g/dL indicating intermediate severity; and >10 g/dL representing lower risk). Age was categorized into 28–49, 50–65, and ≥66 years to capture the gradient of perioperative risk associated with aging. The variables pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus were retained as dichotomous (1 point for absence and 2 points for presence), based on data availability in medical records. Obesity, assessed using body mass index (BMI) (≤29.9, 30–34.9, and ≥35 kg/m2), assigned the highest score to cases with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2.

This simplification ensured data consistency and reproducibility while reducing subjectivity. The modifications rendered the score more objective, feasible, and aligned with the SUS context, aiming to assess whether patients with greater clinical severity were, in fact, being prioritized in surgical scheduling.

The adapted score preserved the principle of progressive weighting according to clinical severity but streamlined the assessment by prioritizing demographic and clinical data that are readily retrievable. Complex operative parameters were replaced by indicators more closely aligned with the practical realities of surgical waiting-list management in the public healthcare setting.

The cutoff points adopted for surgical priority classification (low, moderate, and high) were defined based on principles of clinical plausibility, the empirical distribution of scores within the study sample, and consistency with prioritization models previously described in the literature. The total score, ranging from 8 to 21 points, resulted from the ordinal summation of independent clinical domains, each reflecting disease severity, perioperative risk, or functional impact of the gynecologic condition.

Low priority (≤12 points) corresponded to patients with a lower burden of aggravating factors, predominantly presenting with controllable symptoms, absence of severe anemia, and fewer comorbidities. The moderate-priority range (13–15 points) encompassed the largest proportion of the sample, reflecting the predominant profile of patients with chronic benign conditions, persistent symptoms, and intermediate risk—a pattern consistent with findings from other public healthcare systems. High priority (>15 points) was reserved for patients with greater clinical complexity, higher functional impairment, and/or objective markers of severity, such as severe anemia, multiple comorbidities, or prolonged symptom duration.

These cutoff points were discussed and agreed upon during the modified Delphi process, taking into account not only clinical severity but also operational feasibility and the need for practical discrimination between risk groups. Although formal predictive performance metrics (such as area under the curve or calibration) were not derived, the adopted thresholds demonstrated internal consistency and the ability to stratify patients according to progressively more complex clinical profiles, supporting their face validity and clinical plausibility within the SUS context.

Variables were organized on an ordinal scale, as presented in

Table 2, allowing classification of patients into the following categories:

Low Priority (≤12 points);

Moderate Priority (13–15 points);

High Priority (>15 points).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, version 4.4.2), employing specific packages for data manipulation (dplyr, tidyr, stringr, purrr), visualization (ggplot2, ggpubr), and statistical modeling (MASS, rstatix, VGAM, ordinal, broom).

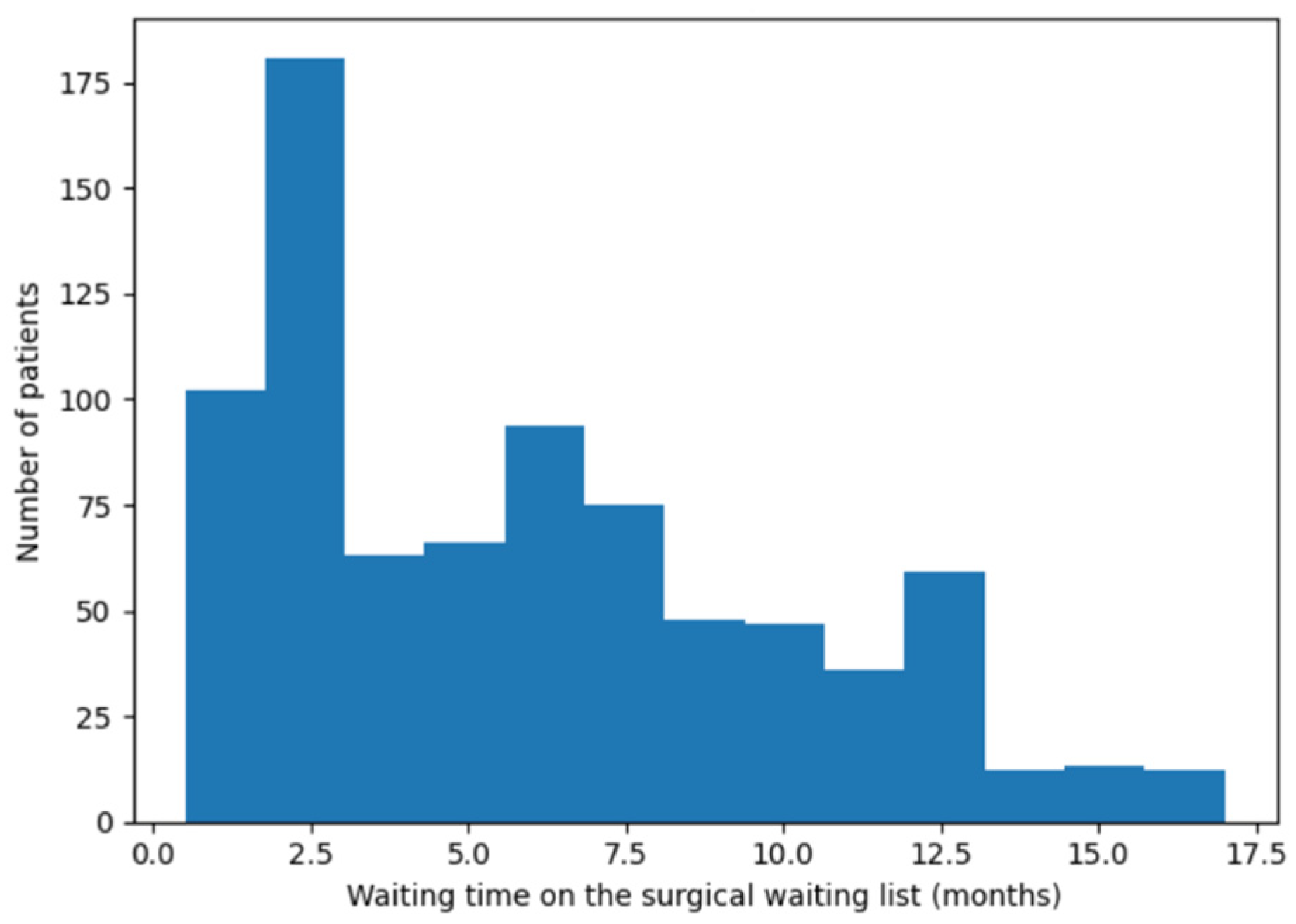

An initial descriptive analysis was conducted to characterize the demographic, clinical, and surgical features of the sample. The distribution of surgical waiting time was assessed through graphical inspection (histogram) and summary measures of central tendency and dispersion.

Given that ordinal regression models with very large coefficients are particularly sensitive to quasi-separation, potentially yielding unstable or inflated estimates, the model was fitted using penalized likelihood estimation with Firth’s bias correction. This approach reduces estimation bias and improves numerical stability of the coefficients, especially in scenarios of partial separation between outcome levels. Firth’s correction was adopted for its regularizing effect on the likelihood, constraining coefficient magnitude and ensuring more robust inference without compromising the ordinal structure of the model.

To analyze surgical waiting time, quantile regression at the median (τ = 0.50) was employed, as waiting time exhibited a right-skewed distribution and was highly susceptible to the influence of extreme values. The median was therefore chosen to provide a robust and clinically interpretable estimate of central tendency, reflecting the typical waiting experience of patients in the surgical queue. More extreme quantiles (e.g., τ = 0.25 or τ = 0.75) were not explored, as the primary objective was to assess whether greater clinical severity translated into shorter waiting times for the majority of patients, rather than to characterize extreme waiting scenarios. This model allowed estimation of the effect of clinical criteria on median waiting time, with coefficients expressed in months.

Additionally, the association between the total clinical score and median surgical waiting time was evaluated using simple quantile regression, quantifying the change in waiting time associated with unit increments in the total score. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance level set at 5%.