A Survey of Prenatal Testing and Pregnancy Termination Among Muslim Women in Mixed Jewish-Arab Cities Versus Predominantly Arab Cities in Israel

Abstract

1. Introduction

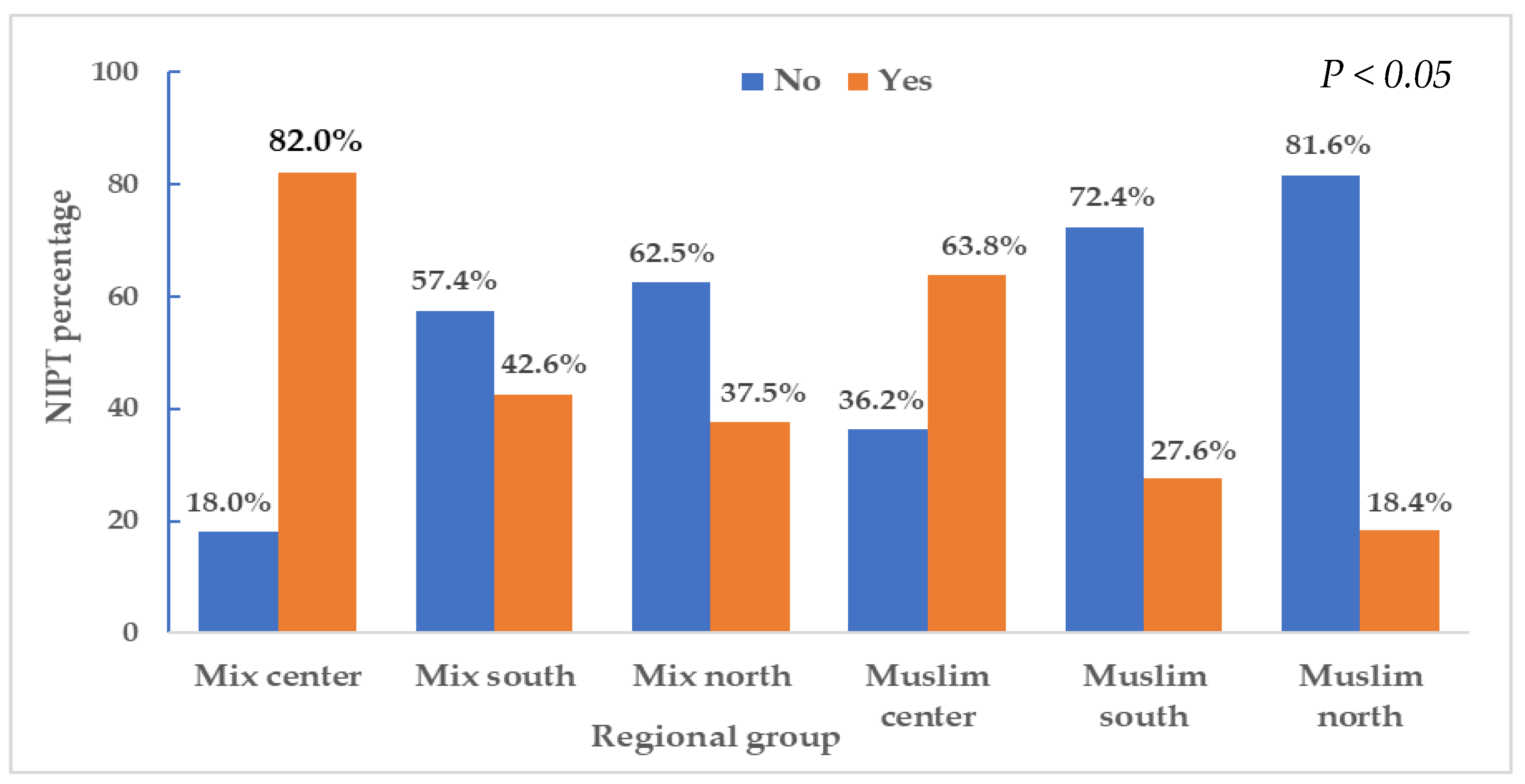

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Study Design and Population

4.2. Data Collection and Definition of the Study Variables

4.3. Statistical Methods

4.4. Ethical Aspects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACOG | American College for Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| AC | Amniocentesis |

| CVS | Chorionic villus sampling |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| M | Means |

| NIPT | Non-Invasive Prenatal Test |

| R | Ranges |

| SD | Standard deviations |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Science |

References

- Frohwirth, L.; Coleman, M.; Moore, A.M. Managing Religion and Morality Within the Abortion Experience: Qualitative Interviews with Women Obtaining Abortions in the U.S. World Med. Health Policy 2018, 10, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, A.; Na’amnih, W.; Tarabeih, M. Prenatal Diagnosis and Pregnancy Termination in Jewish and Muslim Women with a Deaf Child in Israel. Children 2023, 10, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, A.; Tarabeih, M. Prenatal Testing and Pregnancy Termination Among Muslim Women Living in Israel Who Have Given Birth to a Child with a Genetic Disease. J. Relig. Health 2023, 62, 3215–3229. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk, A.; Valdimarsdottir, M. Understanding Americans’ abortion attitudes: The role of the local religious context. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 71, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk, A. Cross-National Public Opinion about Homosexuality: Examining Attitudes Across the Globe; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, M.; Savage, S. Values and Religion in Rural America: Attitudes Toward Abortion and Same-Sex Relations; University of New Hampshire: Durham, NH, USA, 2006; [Adobe Digital Editions Version]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jelen, T.G. The subjective bases of abortion attitudes: A cross-national comparison of religious traditions. Politics Relig. 2014, 7, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carol, S.; Milewski, N. Attitudes toward abortion among the Muslim minority and non-Muslim majority in cross-national perspective: Can religiosity explain the differences? Socio Relig. 2017, 78, 456–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, A.; Tarabeih, M. Prenatal Tests Undertaken by Muslim Women Who Underwent IVF Treatment, Secular Versus Religious: An Israeli Study. J. Relig. Health 2023, 62, 3204–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesser-Edelsburg, A.; Shahbari, N.A. Decision-making on terminating pregnancy for Moslem Arab women pregnant with fetuses with congenital anomalies: Maternal affect and doctor-patient communication. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli Ministry of Health. Pregnancy Termination According to the Law 1990–2016. 2017. Available online: https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/preg1990_2016.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2021).[Green Version]

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Applications for Pregnancy Termination in 2020. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2022/008/05_22_008b.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2024). (In Hebrew)[Green Version]

- Central Bureau of Statistics, State of Israel. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il (accessed on 13 February 2025).[Green Version]

- Central Bureau of Statistics, State of Israel. Applications for Pregnancy Termination in 2017–2018. Jerusalem. 2019. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/DocLib/2019/394/05_19_394b.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2024). (In Hebrew)[Green Version]

- Dery, A.M.; Carmi, R.; Vardi, I.S. Attitudes toward the acceptability of reasons for pregnancy termination due to fetal abnormalities among prenatal care providers and consumers in Israel. Prenat. Diagn. 2008, 28, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinshpun-Cohen, J.; Miron-Shatz, T.; Berkenstet, M.; Pras, E. The limited effect of information on Israeli pregnant women at advanced maternal age who decide to undergo amniocentesis. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2015, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, C.; Romano-Zelekha, O.; Green, M.S.; Shohat, T. Factors affecting performance of prenatal genetic testing by Israeli Jewish women. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 120A, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, C.; Romano-Zelekha, O.; Green, M.S.; Shohat, T. Utilization of prenatal genetic testing by Israeli Moslem women: A national survey. Clin. Genet. 2004, 65, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remennick, L. The quest for the perfect baby: Why do Israeli women seek prenatal genetic testing? Sociol. Health Illn. 2006, 28, 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi-Dain, L.; Singer, A.; Petersen, O.B.; Lou, S.; Vogel, I. Trends in Non-invasive Prenatal Screening and Invasive Testing in Denmark (2000–2019) and Israel (2011–2019). Front. Med. 2021, 87, 68997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsen, K.; Na’amnah, W.; Lesser, Y.; Volovik, I.; Cohen, D.; Shohat, T. Determinates of underutilization of amniocentesis among Israeli Arab women. Prenat. Diagn. 2010, 30, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugoff, L.; Norton, M.E.; Kuller, J.A. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, B2–B9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S.; Hacohen, N.; Meiner, V.; Yagel, S.; Zenvirt, S.; Shkedi-Rafid, S.; Macarov, M.; Valsky, D.V.; Porat, S.; Yanai, N.; et al. Universal chromosomal microarray analysis reveals high proportion of copy-number variants in low-risk pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allyse, M.; Minear, M.A.; Berson, E.; Sridhar, S.; Rote, M.; Hung, A.; Chandrasekharan, S. Non-invasive prenatal testing: A review of international implementation and challenges. Int. J. Womens Health 2015, 7, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravitsky, V.; Roy, M.C.; Haidar, H.; Henneman, L.; Marshall, J.; Newson, A.J.; Ngan, O.M.Y.; Nov-Klaiman, T. The Emergence and Global Spread of Noninvasive Prenatal Testing. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2021, 22, 309–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meij, K.R.M. Implementing Genome-Wide Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing in a National Prenatal Screening Program. Ph.D. Thesis, Research and Graduation Internal, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, N.C.; Kaimal, A.J.; Dugoff, L.; Norton, M.E. Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities: ACOG practice bulletin, number 226. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, e48–e69. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Israel. Available online: https://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/Genetics/checks/during_pregnancy/Pages/screening_tests.aspx (accessed on 27 January 2024).

- Peters, I.A.; Heetkamp, K.M.; Ursem, N.T.C.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Denktas, S.; Knapen, M.F.C.M. Ethnicity and language proficiency differences in the provision of and intention to use prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome and congenital anomalies. A prospective, non-selected, register-based study in the Netherlands. Matern. Child. Health J. 2018, 22, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitsels-van der Wal, J.; Mannien, J.; Gitsels, L.A.; Reinders, H.S.; Verhoeven, P.S.; Ghaly, M.M.; Klomp, T.; Hutton, E.K. Prenatal screening for congenital anomalies: Exploring midwives’ perceptions of counseling clients with religious backgrounds. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitsels-van der Wal, J.T.; Manniën, J.; Ghaly, M.M.; Verhoeven, P.S.; Hutton, E.K.; Reinders, H.S. The role of religion in decision-making on antenatal screening of congenital anomalies: A qualitative study amongst Muslim Turkish origin immigrants. Midwifery 2014, 30, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakst, S.; Romano-Zelekha, O.; Ostrovsky, J.; Shohat, T. Determinants associated with making prenatal screening decisions in a national study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 39, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitsels-Van Der Wal, J.T.; Verhoeven, P.S.; Manniën, J.; Martin, L.; Reinders, H.S.; Spelten, E.; Hutton, E.K. Factors affecting the uptake of prenatal screening tests for congenital anomalies; a multicenter prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jader, L.; Parry-Langdon, N.; Smith, R. Survey of attitudes of pregnant women towards Down syndrome screening. Prenat. Diagn. 2000, 20, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, A.; Wasserman, D. Informed consent and prenatal testing: The Kennedy-Brownback Act. Virtual Mentor. 2009, 11, 721–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, R.; Puddicombe, D.; Hockley, C.; Redshaw, M. Offer and uptake of prenatal screening for Down syndrome in women from different social and ethnic backgrounds. Prenat. Diagn. 2008, 28, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posthumus, A.G.; Peters, I.A.; Borsboom, G.J.; Knapen, M.F.C.M.; Bonsel, G.J. Inequalities in uptake of prenatal screening according to ethnicity and socio-economic status in the four largest cities of the Netherlands (2011–2013). Prenat. Diagn. 2017, 37, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormandy, E.; Michie, S.; Hooper, R.; Marteau, T.M. Low uptake of prenatal screening for Down syndrome in minority ethnic groups and socially deprived groups: A reflection of women’s attitudes or a failure to facilitate informed choices? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppermann, M.; Learman, L.A.; Gates, E.; Gregorich, S.E.; Nease, R.F., Jr.; Lewis, J.; Washington, A.E. Beyond race or ethnicity and socioeconomic status: Predictors of prenatal testing for Down syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, P. The beginning of life issues: An Islamic perspective. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 663–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, H.E. Developments in stem cell research and therapeutic cloning: Islamic ethical positions. A review. Bioethics 2012, 26, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.F.M.; Hashi, A.A.; bin Nurumala, M.S.; bin Md Isa, M.L. Islamic oral judgment on abortion and it’s nursing applications: Expository analysis. Enferm. Clin. 2018, 28, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitsels-van der Wal, J.T.; Martin, L.; Mannien, J.; Verhoeven, P.; Hutton, E.K.; Reinders, H.S. Antenatal counseling for congenital anomaly tests: Pregnant Moslem Moroccan women’s preferences. Midwifery 2015, 31, e50–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serour, G.I. Ethical issues in human reproduction: Islamic perspectives. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2013, 29, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsianakas, V.; Liamputtong, P. Prenatal testing: The perceptions and experiences of Muslim women in Australia. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2002, 20, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Brameld, K.; Bower, C.; Dickinson, J.E.; Goldblatt, J.; Hadlow, N.; Hewitt, B.; Murch, A.; Murphy, A.; Stock, R.; et al. Socio-demographic disparities in the uptake of prenatal screening and diagnosis in Western Australia. Austr. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011, 51, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoy, M.E.; Iruretagoyena, J.I.; Birkeland, L.E.; Petty, E.M. The impact of insurance on equitable access to non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPT): Private insurance may not pay. J. Community Genet. 2021, 12, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, L.; Dolfin, T.; Shohat, T.; Halpern, G.J.; Reish, O.; Fejgin, M. Prenatal diagnosis for detecting congenital malformations: Acceptance among Israeli Arab women. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2000, 2, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van der Meij, K.R.M.; Kooij, C.; Bekker, M.N.; Galjaard, R.H.; Henneman, L.; Dutch NIPT Consortium. Non-invasive prenatal test uptake in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. Prenat. Diagn. 2021, 41, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, A.; Tarabeih, M. Prenatal tests undergone by Moslem women who live with an abnormal child compared to women who live with normal child. Glob. J. Reprod. Med. 2021, 8, 5556746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Barclay, J.; Poulton, A.; Hutchinson, B.; Halliday, J.L. Prenatal diagnosis and socioeconomic status in the non-invasive prenatal testing era: A population-based study. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 58, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pos, O.; Budis, J.; Szemes, T. Recent trends in prenatal genetic screening testing. F1000Res 2019, 8, F1000 Faculty Rev-764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotogora, J. Autosomal recessive diseases among the Israeli Arabs. Hum. Genet. 2019, 38, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Green, J.M.; Hewison, J. Attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy for thalassemia in pregnant Pakistani women in the North of England. Prenat. Diagn. 2006, 26, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, A.; Azuri, P.; Ezra, D.; Halabi, S. Prenatal tests and pregnancy termination among Muslim women in Israel. Asian J. Med. Health Res. 2020, 62, 3215–3229. [Google Scholar]

- Romano-Zelekha, O.; Ostrovsky, J.; Shohat, T. Increasing rates of prenatal testing among Jewish and Arab women in Israel over one decade. Public. Health Genom. 2014, 17, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aqeel, A.I. Ethical guidelines in genetics and genomics. An Islamic perspective. Saudi Med. J. 2005, 26, 1862–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka, S.I.; Hassold, T.J.; Hunt, P.A. Human aneuploidy: Mechanisms and new insights into an age-old problem. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikwar, M.; MacFarlane, A.J.; Marchetti, F. Mechanisms of oocyte aneuploidy associated with advanced maternal age. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2020, 785, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Chang, E.J.; Bendikson, K.A. Advanced paternal age and the risk of spontaneous abortion: An analysis of the combined 2011–2013 and 2013–2015 National Survey of Family Growth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 476.e1–476.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). Statistical Abstract of Israel 2021, No. 72, Jerusalem. 2021. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/publications/Pages/2021/Statistical-Abstract-of-Israel-2021-No-72.aspx (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Haj-Yahya, N.H.; Khalaily, M.; Rudnitzky, A. The Israel Democracy Institute: Statistical Report on Arab Society in Israel: 2021. 2022. Available online: https://en.idi.org.il/articles/38540 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

| Region | Criterion | M | SD | Criterion | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Center | Age | 39.7 | 2.3 | Number of miscarriages | 1.7 | 0.5 |

| Mixed South | F = 143.9 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 35.9 | 5.6 | F = 103.0 *, ω2 = 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Mixed North | 29.6 | 9.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | ||

| Muslim Center | 40.0 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Muslim South | 37.1 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 0.2 | ||

| Muslim North | 27.5 | 8.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| Mixed Center | Number of children | 5.1 | 1.4 | Number of abortions following abnormal diagnosis of the child | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| Mixed South | F = 164.1 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | |

| Mixed North | 2.7 | 2.7 | F = 43.8 *, ω2 = 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| Muslim Center | 8.1 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | ||

| Muslim South | 6.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 | ||

| Muslim North | 3.5 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | ||

| Mixed Center | Number of pregnancies | 7.9 | 1.7 | |||

| Mixed South | F = 115.4 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 6.0 | 3.1 | |||

| Mixed North | 4.1 | 4.1 | ||||

| Muslim Center | 9.8 | 1.6 | ||||

| Muslim South | 8.2 | 2.0 | ||||

| Muslim North | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| Region | Criterion | M | SD | Criterion | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Center | Invasive tests for diagnosing | 5.7 | 1.3 | Planned abortion induces anger | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| Mixed South | abnormality | 5.7 | 1.2 | F = 160.1 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 3.4 | 1.8 |

| Mixed North | F = 238.5 *, ω2 = 0.5 | 6.3 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 1.8 | |

| Muslim Center | 2.3 | 0.9 | 6.8 | 0.5 | ||

| Muslim South | 3.6 | 1.4 | 5.7 | 1.2 | ||

| Muslim North | 5.5 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 1.7 | ||

| Mixed Center | Consulting with a religious authority/figure to consider invasive tests | 3.5 | 2.0 | Planned abortion induces depression | 3.9 | 2.0 |

| Mixed South | 2.9 | 1.8 | F = 163.3 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 3.4 | 1.8 | |

| Mixed North | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | ||

| Muslim Center | F = 113.3 *, ω2 = 0.3 | 6.3 | 1.2 | 6.8 | 0.4 | |

| Muslim South | 4.6 | 2.0 | 5.6 | 1.2 | ||

| Muslim North | 3.1 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Mixed Center | Belief in religious values and | 4.1 | 2.3 | Planned abortion induces sadness | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| Mixed South | morals | 4.2 | 2.1 | F = 164.4 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 3.4 | 1.7 |

| Mixed North | F = 113.1 *, ω2 = 0.3 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | |

| Muslim Center | 6.8 | 0.4 | 6.8 | 0.4 | ||

| Muslim South | 6.3 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 1.2 | ||

| Muslim North | 4.9 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Mixed Center | Behaving in line with religious | 4.2 | 2.3 | Planned abortion induces helplessness | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| Mixed South | values and tradition | 4.2 | 2.1 | F = 164.9 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 3.4 | 1.7 |

| Mixed North | F = 11.6 *, ω2 = 0.3 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.8 | |

| Muslim Center | 6.8 | 0.4 | 6.8 | 0.4 | ||

| Muslim South | 6.3 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 1.2 | ||

| Muslim North | 5.0 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Mixed Center | Planned abortion induces guilt | 4.2 | 2.3 | Planned abortion when fetus has | 4.7 | 1.7 |

| Mixed South | F = 113.4 *, ω2 = 0.3 | 4.2 | 2.1 | abnormalities | 5.2 | 1.6 |

| Mixed North | 3.4 | 1.9 | F = 122.1 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 5.8 | 1.7 | |

| Muslim Center | 6.9 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Muslim South | 6.4 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 1.7 | ||

| Muslim North | 5.0 | 1.2 | 5.4 | 2.0 | ||

| Mixed Center | Religious authorities should | 3.5 | 2.0 | Friends’ support on planned | 3.8 | 2.4 |

| Mixed South | confirm abortion (if there are | 2.9 | 1.8 | abortion (due to abnormalities) | 4.4 | 2.1 |

| Mixed North | abnormalities with the fetus) | 2.4 | 2.0 | F = 145.2 *, ω2 = 0.4 | 5.7 | 2.0 |

| Muslim Center | F = 98.4 *, ω2 = 0.3 | 6.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | |

| Muslim South Muslim North | 4.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.3 | ||

| 2.6 | 2.2 | 5.0 | 2.3 |

| Variable | Mixed Cities | Arab Cities | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(<35) N = 208 n (%) | Age(≥35) N = 376 n (%) | Age(<35) N = 210 n (%) | Age(≥35) N = 287 n (%) | ||

| Had a spontaneous conception | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 155 (74.5%) | 41 (10.9%) | 210 (100%) | 105 (36.6%) | |

| No | 53 (25.5%) | 335 (89.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 182 (63.4%) | |

| Doing a Non-Invasive Prenatal Test | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 7 (3.4%) | 328 (87.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 186 (64.8%) | |

| No | 201 (96.6%) | 48 (12.8%) | 210 (100.0%) | 101 (35.2%) | |

| Birth of an abnormal child in the past | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 304 (80.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 201 (70.0%) | |

| No | 208 (100.0%) | 72 (19.1%) | 210 (100.0%) | 86 (30.0%) | |

| Prenatal amniocentesis/chorionic villus sampling | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 320 (85.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 200 (69.7%) | |

| No | 208 (100.0%) | 56 (14.9%) | 210 (100.0%) | 87 (30.3%) | |

| Received genetic consultancy before prenatal diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 42 (20.2%) | 347 (92.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 192 (66.9%) | |

| No | 166 (79.8%) | 29 (7.7%) | 210 (100.0%) | 95 (33.1%) | |

| Received physician consultancy before prenatal diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 59 (28.4%) | 358 (95.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 224 (78.0%) | |

| No | 149 (71.6%) | 18 (4.8%) | 210 (100.0%) | 63 (22.0%) | |

| Pregnancy termination (after a positive prenatal diagnosis for abnormalities) | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 13 (6.3%) | 332 (88.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 184 (64.1%) | |

| No | 195 (93.7%) | 44 (11.7%) | 210 (100.0%) | 103 (35.9%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarabeih, M.; Amiel, A.; Na’amnih, W. A Survey of Prenatal Testing and Pregnancy Termination Among Muslim Women in Mixed Jewish-Arab Cities Versus Predominantly Arab Cities in Israel. Women 2025, 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030030

Tarabeih M, Amiel A, Na’amnih W. A Survey of Prenatal Testing and Pregnancy Termination Among Muslim Women in Mixed Jewish-Arab Cities Versus Predominantly Arab Cities in Israel. Women. 2025; 5(3):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030030

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarabeih, Mahdi, Aliza Amiel, and Wasef Na’amnih. 2025. "A Survey of Prenatal Testing and Pregnancy Termination Among Muslim Women in Mixed Jewish-Arab Cities Versus Predominantly Arab Cities in Israel" Women 5, no. 3: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030030

APA StyleTarabeih, M., Amiel, A., & Na’amnih, W. (2025). A Survey of Prenatal Testing and Pregnancy Termination Among Muslim Women in Mixed Jewish-Arab Cities Versus Predominantly Arab Cities in Israel. Women, 5(3), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030030