1. Introduction

Maternal mental health conditions are among the most common complications experienced by women during pregnancy and childbirth [

1]. These conditions affect 800,000 families in the United States (US) each year [

1]. Some of the major mental health issues encountered by pregnant and postpartum women residing in underserved and low-income areas in the US include perinatal depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders [

1].

Perinatal depression is estimated to affect around 14% of childbearing individuals [

1]. In a 2020 study, 13.2% of patients self-reported postpartum depression symptoms using the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) [

2]. These symptoms were identified as postpartum depressive symptoms if the mother answered “always” or “often” to an adapted PHQ-2 questionnaire [

2]. The prevalence was higher among women who identified as Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Asian/Pacific Islander, those who had completed ≤12 years of education, and those who were not married [

2]. The prevalence was also higher among women who used the Women, Infants, and Children program (WIC) during their pregnancy, had Medicaid during delivery, and smoked cigarettes during pregnancy or postpartum [

2].

Anxiety disorders are also common mental health conditions affecting perinatal women. A total of 15% of pregnant patients reported anxiety symptoms, which have been found to have strong associations with a lower income and racially/ethnically marginalized pregnant people [

3]. Peripartum anxiety disorders are increasingly being diagnosed in US women, with the rate of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders nearly doubling from 2015 to 2020 [

4,

5,

6]. By 2020, 28% of pregnant or postpartum women were reported to receive a perinatal mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis [

6,

7]. Some of the major risk factors include having experienced intimate partner violence, housing instability, history of substance abuse, and low social support [

8]. It has also been found that Black females were more likely to report social determinants of health such as substance use or intimate partner violence co-occurring with their perinatal mood and anxiety disorders than Hispanic or White females [

8]. In a study focusing on perinatal depression in Black women, a higher financial status was associated with a significant protective effect from perinatal depression [

7]. Most importantly, individual and environmental determinants of health have been found to have a significant association with perinatal maternal distress [

9]. This in turn highlights the need for anxiety screening, education in perinatal appointments, and more effective patient–provider communication strategies to prevent worsening of symptoms and health consequences of such mental health conditions.

A third reported perinatal and postpartum mental health condition in US women is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which is estimated to affect around 9% of childbearing individuals [

1]. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities have been found to be significantly associated with PTSD diagnosis [

4]. These have been partly attributed to disadvantaged women being at higher risk of being exposed to traumatic events. In 2025, a study by Kofman et al. showed differences between severity of PTSD symptoms experienced based on traumatic events and racial/ethnic identification, whereby Black and Hispanic females were more likely to report trauma-initiated PTSD symptoms when compared to White females, with some events based on their personal experiences [

4].

Finally, substance use disorder (SUD) in pregnancy is also a comorbidity identified in women who are incapable of quitting the use of toxic substances while pregnant [

5]. Some of the most frequently abused substances associated with perinatal females include tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and opioids. US women are at the highest risk for development of an SUD during their reproductive years, particularly if their access to mental health services is limited due to financial constraints [

5]. Postpartum substance use was most common among women experiencing six or more stressful life events in the year before giving birth or four adverse childhood experiences [

5]. Additionally, higher substance use in this population has also been found to be associated with depression, anxiety, adverse childhood experiences, and stressful life events [

5]. As such, it is crucial to address risk factors of such mental health illnesses in vulnerable US pregnant and postpartum women to ensure improved maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Major challenges affecting vulnerable and underserved pregnant and postpartum women in accessing mental health services include financial barriers, social stigmas surrounding mood and anxiety disorders, low understanding of treatment options, and a lack of time for treatment [

10]. Health care providers have encouraged protocols for the screening of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders to ensure referrals to behavioral health providers are made and followed through [

11]. There is also an increased emphasis on patient–provider communication, encouraging patients to actively communicate their symptoms to their providers following increased awareness of the need for culturally competent strategies in treating patients to take into consideration their social determinants of health as major factors contributing to their underlying condition [

11]. There has also been an increase in telehealth behavioral services being offered, which has become one way that access to behavioral health services can be improved [

11,

12]. However, the United States still lacks an overarching health care system capable of meeting the needs of perinatal people [

13]. Challenges remain the greatest among underserved populations, although the issue of access to mental health services is gaining more recognition and awareness [

13]. Additionally, current health care policies affecting accessible, affordable mental health services through new insurance restrictions, funding cuts, and program eliminations disproportionately impact high-risk maternal populations with serious mental illnesses and SUDs, particularly those residing in low-income and rural neighborhoods [

14,

15,

16].

The purpose of this scoping review is to identify major social determinants of health and barriers affecting access to mental health services in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. It will also explore commonly reported mental health issues and subsequent maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes resulting from limited access to mental health services. Finally, this review will examine the scope of existing evidence-based interventions and dissemination and implementation strategies that were developed and implemented to increase accessibility to mental health treatment in high-risk pregnant and postpartum women. Findings from our review will provide future recommendations to address the gap in accessibility and affordability of mental health services in US pregnant and postpartum women residing in underserved communities.

2. Methods

This study utilized the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews, in addition to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-SCR) as a reference checklist [

17]. The Arksey and O’Malley Framework was used to guide the review process [

18].This framework consists of the following steps: (1) identifying research questions, (2) conducting the literature review, (3) choosing relevant studies, (4) organizing the data systematically, and (5) compiling, summarizing, and presenting findings. This process enhances the reliability and validity of the study as well as ensures its transparency.

2.1. Step 1: Identifying Research Questions

Five guiding research questions for the scoping review were formulated for this study: (1) What are the major social determinants of health influencing access to mental health services in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States? (2) At which levels of the socioecological model are barriers to accessing mental health services in pregnant and postpartum maternal populations distributed? (3) What are the most commonly reported mental health issues and subsequent maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes resulting from limited access to mental health services? (4) What is the scope of evidence-based strategies and interventions that exist to address disparities in accessing mental health services during pregnancy and after delivery? and (5) What are the recommendations for future dissemination, implementation, and evaluation of mental health interventions and strategies to increase accessibility to mental health treatment in high-risk pregnant and postpartum women?

2.2. Step 2: Conducting the Literature Review

MeSH and keyword terms for the search strategy were developed in collaboration with a research librarian (M.K.K.), who is an expert in scoping review protocols. The search terms included pregnant women, postpartum women, maternal mental health, mental health issues, depression, anxiety, PTSD, therapy, psychologist, psychiatrist, mental health services, disparities, limited access, health inequities, underserved, and low-income. Three major databases were searched (PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library) to ensure comprehensive coverage. The literature review was completed over one month, from May 2025 to June 2025, using the software Covidence. The screening of the titles and abstracts of the articles was initially carried out by pairs of co-authors (K.E., J.M., M.B.F., E.K., A.C., G.O.). Conflicts were resolved by co-author (D.L.) and senior author (L.S.). Full-text screening was then carried out by primary author (K.E.) and senior author (L.S.).

Inclusion Criteria:

The articles that were included were descriptive, observational, and experimental studies published in English between 2015 to 2025 to identify major recent barriers to mental health care services in our population of interest in the past decade. These studies specifically focused on the following four ideas: (1) examining socioeconomic, geographic, racial/ethnic, and other barriers influencing access to mental health services in pregnant and postpartum women; (2) exploring the impact of limited access to essential mental health services on pregnant and postpartum maternal health outcomes; (3) exploring interventions and strategies that improved access to needed mental health services in pregnant and postpartum women; and (4) exploring the impact of limited access to analgesia on maternal and neonatal outcomes all within adult women of reproductive age (ages 18 to 49 years).

Exclusion Criteria:

Excluded studies included published conference abstracts, systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. Additionally, articles were excluded if they focused on adolescent females and/or menopausal females, and if they were not written in English.

2.3. Step 3: Selecting Studies Relevant to the Research Questions

Co-authors (KE and MS) extracted data and summarized data from the relevant articles. Senior author (LS) then reviewed all tabulated data to resolve any discrepancies, particularly in the stratification of barriers across barrier theme categories and the different levels of the socioecological model. Final data tabulation agreements were reached through consensus following discussions between the senior author and the two co-authors.

Summary tables included one evidence table describing study characteristics and type of SDOH, Healthy People 2030 domain, along with type of mental health issue, reported mental health outcomes in pregnant and postpartum women, and major findings. The Healthy People 2030 domain is a set of science-based objectives with goals to observe progress, encourage, and focus on action. A total of 16 SDOH objectives were added to the Healthy People 2030 after the World Health Organization’s (WHO) call to address SDOH to preserve health and quality of life [

19].

Table 1 explores barriers experienced by US pregnant and postpartum populations in accessing needed mental health services.

Table 2 displays most commonly reported mental health issues and subsequent maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes resulting from limited access to mental health services.

Table 3 highlights evidence-based strategies and interventions that exist to address disparities in accessing mental health services during pregnancy and postpartum periods.

Supplementary Table S2 is a lesson learned table where thematic qualitative content analysis was carried out to identify similar themes in future directions across studies.

2.4. Steps 4 and 5: Data Charting and Collation, Summarization, and Reporting of Results

Study characteristics were tabulated for primary author/year, study design, sample size, study population, age range, pregnancy/postpartum period, and study purpose for each of the articles included in the review (

Supplementary Table S1). Identified barriers encountered by underserved pregnant and postpartum women in accessing mental health services were initially classified based on the socioecological model and then further classified based on barrier theme categories (

Table 1). Maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes resulting from specific mental health issues (

Table 2), as well as relevant and effective evidence-based strategies used in the design and delivery of interventions, were also tabulated (

Table 3).

Supplementary Table S2 is an application of the three phases of qualitative content analysis to inform future evidence-based strategies to increase accessibility to mental health treatment in high-risk pregnant and postpartum women. These phases encompass (1) preparation phase where the unit of analysis is selected, (2) organizing phase where the researcher makes sense of the data and whole, and (3) reporting phase where the researcher displays the data using a model, conceptual system, conceptual map, or categories [

20].

Table 1.

Barriers experienced by US underserved and rural maternal populations in accessing mental health care.

Table 1.

Barriers experienced by US underserved and rural maternal populations in accessing mental health care.

| Article # | Primary Author/Year | Barriers Encountered by Underserved Pregnant and Postpartum Women in

Accessing Mental Health Services | Socioecological Level | Barrier Theme Categories |

|---|

| | | |

Ind

|

Inter

|

Org

|

Com

|

Sol/Pol

|

Limited Health Care

Accessibility,

Affordability, and Quality

|

Geographic and Transportation Challenges

|

Social Norms and

Family-

Related Issues

|

Communication and Health Literacy Challenges

|

Distrust in Medical

Institutions/Health Care System

|

Financial and Childcare Challenges

|

Digital

Access and Literacy

|

Racism and Discrimination

|

Language Barriers, Cultural Barriers, and Stigma-Related Challenges

|

Structural and Regulatory Challenges in Health Care Settings

|

Inadequate Patient

Education Regarding Health Conditions, Symptom Management and Treatment

|

COVID-19

|

|---|

| 1 | Baggett et al., 2021 [21] | Inadequate access to care | x | | x | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Racial disparities | x | | | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | |

| Distrust in research institutions | x | | | | x | | | | | x | | | | | | | |

| Transportation issues | x | | x | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Costs associated with participating in research | | | x | | | x | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Lack of digital access | x | | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | |

| 2 | Bhat et al., 2018 [22] | Childcare responsibilities | x | x | | x | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Access to transportation | x | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Stigma around mental health care | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Limited resources due to rural area | | | x | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Difficulty in knowing what resource text message came from | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | | | | | |

| 3 | Bryant et al., 2023 [23] | Racial disparities | x | | | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | |

| Financial challenges | x | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Lack of childcare or maternity leave | x | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Access to transportation | x | | | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Access to technology | x | | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | |

| Health literacy | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | | | | | |

| 5 | Evans et al., 2017 [24] | Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Social support | x | x | | x | | | | x | | | | | | | | | |

| Financial challenges | x | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Lack of education | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | | | | | |

| 6 | Guille et al., 2022 [25] | Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Transportation issues | x | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Stigmas with mental health treatment | x | | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| 7 | Hanson et al., 2023 [26] | Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Transportation issues | x | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Stigmas with mental health treatment | x | | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Lack of social support | x | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | | | | |

| Housing instability | x | | x | x | | | x | | | | x | | | | | | |

| 8 | Harris et al., 2025 [27] | Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Transportation issues | x | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Stigmas with mental health treatment | x | | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Lack of education | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | | | | | |

| Financial challenges | x | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Housing instability | x | | x | x | x | | x | | | | x | | | | | | |

| 9 | Hughes et al., 2023 [28] | Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Stigmas with mental health treatment | x | | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Race/ethnicity | x | | | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | |

| Financial/insurance challenges | x | | x | | | x | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| 10 | Jeanne Ruiz et al., 2019 [29] | Race/ethnicity | x | | | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | |

| Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Health literacy | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | | | |

| 11 | Jesse et al., 2015 [30] | Race/ethnicity | x | | | x | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | |

| Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Financial challenges | x | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| 12 | Lewis et al., 2024 [31] | Financial challenges | x | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 13 | Lord & Rao., 2025 [32] | Financial challenges | x | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Health care access | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| 14 | McKimmy et al., 2023 [33] | Lack of transportation to perinatal care visits | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Lack of culturally tailored interventions and language barriers | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Immigration status | x | | x | x | x | x | | | | | | | | x | x | | |

| Financial constraints | x | | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Stigma surrounding mental health | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Cultural oppression | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Discrimination | x | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | x | | | |

| Social isolation | x | x | | x | | | x | x | | | | | | x | | | |

| Employment challenges | | | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Lack of Spanish-speaking mental health professionals in rural communities | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Difficulties with cultural adaptation | x | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | x | | | |

| 15 | Pennington et al., 2023 [34] | Symptom burden | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Lack of knowledge regarding antidepressant adherence and side effects | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Younger age | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Higher comorbidities or disease severity | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Financial constraints | x | | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Language barriers | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Insurance status | x | | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | x | | |

| Employment challenges | | | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Changes in medication during treatment | x | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Lack of adequate postpartum health care visits | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | x | x | |

| Failure of health care provider to provide education on antidepressant side effects, side-effect management, and alternative treatment medication options | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Fear of weight gain, physical dependence, and concerns regarding breastfeeding | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Early medication discontinuation by self or health care provider due to symptom resolution | x | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Treatment burden and treatment fatigue | x | | | | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Lack of geographic access to mental health care | x | | x | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Stigma and misperceptions of antidepressants | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Race | x | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | x | | | |

| 16 | Rodriguez et al., 2021 [35] | Lack of access to postpartum and mental health care | x | | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Location of mental health counselors outside of prenatal clinic home | | | x | | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| 17 | Siegel et al., 2023 [36] | Racism and discrimination | x | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | x | | | |

| Food insecurity | x | | | x | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Challenges in receiving insurance | x | | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | | x | | |

| Lack of health literacy | x | | | x | | | | | x | | | | | | | | |

| COVID-19 pandemic | x | x | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | | | | x |

| Lack of access to behavioral health care | x | | x | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| 18 | Solness et al., 2020 [37] | Increased isolation of living on base | x | x | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Frequent relocations | x | x | x | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Working longer into pregnancy | x | | x | | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Lack of support | | x | | x | | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | |

| Prolonged wait times for in-person services | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | x | | |

| Lack of geographic access to mental health care | x | | x | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Failure of health care providers to recognize perinatal depression or postpartum depression | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Cultural beliefs and rural values | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Stigma surrounding mental health | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| 19 | Tindall et al., 2024 [38] | Lack of geographic access to mental health care | x | | x | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Structural racism | x | x | x | x | x | | | | | x | | | x | x | x | | |

| COVID-19 pandemic | x | x | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | | | | x |

| Limited broadband availability | | | x | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Lack of digital literacy | x | | | x | | | | | | | | x | | | | | x |

| Lack of health literacy | x | | | x | | | | | x | | | | | | | | x |

| Personal expectations | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Perception and utilization of formal health care | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Previous negative health care experiences | x | | x | | | | | | | x | | | | | | | |

| Variability in provider availability | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | x | | |

| Lack of culturally competent care and language barriers | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Medical mistrust due to historical injustice | x | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | | |

| Stigma surrounding mental health | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| 20 | Urizar et al., 2019 [39] | Unemployment | x | | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Racial discrimination | x | x | | x | | | | | | x | | | x | x | | | |

| Lack of prenatal health education | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Language barriers | x | | x | | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| 21 | Zhang et al., 2025 [40] | Lack of focus on postpartum care | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | x | | |

| Gaps in insurance coverage of care | x | | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | x | | |

| Medical costs | x | | x | | x | x | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Lack of transportation to perinatal care visits | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | | | | | | | | | | |

| Lack of childcare support | x | x | | x | | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Housing instability | | | | x | x | | | | | | x | | | | | | |

| Racism and discrimination | x | x | | x | | | | | | | | | x | x | | | |

| Lack of culturally tailored interventions and language barriers | | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | x | | | |

| Inadequate knowledge of postpartum care, postpartum complications, and warning signs | x | | x | x | | | | | | | | | | | | x | |

| Prolonged wait times | | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | x | | |

| Scheduling conflicts | x | | x | | | x | | | | | | | | | x | | |

| Total Number of Barriers | 107 | 30 | 76 | 78 | 28 | 36 | 22 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 24 | 5 | 12 | 28 | 11 | 12 | 4 |

Table 2.

Evidence-based strategies and interventions that exist to address disparities in accessing mental health services pre, post, and during delivery.

Table 2.

Evidence-based strategies and interventions that exist to address disparities in accessing mental health services pre, post, and during delivery.

| Article # | Primary Author/Year | Evidence-Based Strategies Used in the Design and Delivery

of the Intervention that Helped with Intervention Success |

|---|

| 1 | Baggett et al., 2021 [21] | Delivering program through a mobile platform provided adaptability throughout pandemic to meet accessibility disparities Cognitive behavioral therapy integrated into intervention Promoted infant communication skills to develop parenting skills Sessions were coach-facilitated and used evidence-based screening tools (PHQ-2, PHQ-9) Community agency referrals, research staff outreach visits to community agencies and community events, and maternal self-referral were available for recruitment

|

| 2 | Bhat et al., 2018 [22] | Care managers were trained in an engagement session, Problem Solving Therapy (PST), text messaging protocols, and general information on perinatal mental health and pharmacotherapy Care managers participated in weekly consultation calls with the study psychiatrist in which they discussed the CM’s caseload and received treatment recommendations to implement or convey to the patient’s obstetrician

|

| 3 | Bryant et al., 2023 [23] | |

| 4 | Hughes et al., 2023 [28] | Use of the SBIRT Model (Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment) which enabled early detection of the mood and anxiety disorders Use of EPDS to screen for postpartum depression Integration of screening into prenatal appointments and visits

|

| 5 | Jesse et al., 2015 [30] | Beck’s cognitive-behavioral model and Jesse’s bio-psychosocial-spiritual theory provided the theoretical framework for the intervention Intervention included standardized session that were culturally tailored towards participants Women were encouraged to bring support people with them to intervention for peer involvement

|

| 6 | Lewis et al., 2024 [31] | The intervention was based on Social Cognitive Theory and Self-Determination Theory integrating motivational interviewing strategies The intervention was tailored for low-income women Counselors in intervention aimed to increase self-efficacy and emphasized social support

|

| 7 | Mckimmy et al., 2023 [33] | Use of a task-sharing model Peer mentor-led implementation of mental health program Use of lay health workers Culturally competent framework Creation of intimate domestic spaces of support Identity mapping Use of focus groups

|

| 8 | Rodriguez at al., 2021 [35] | |

| 9 | Siegel et al., 2023 [36] | Community-based program utilizing community health workers Multidisciplinary provider referral to program intervention Behavior health and social determinants of health screening Use of bilingual community health workers and telephone interpreters Participant care packages providing direct relief Multiple touchpoints between participants and community or behavioral health worker

|

| 10 | Solness et al., 2020 [37] | Cognitive behavioral therapy framework Internet-based therapies for increased access to care Use of anonymity and flexibility via internet delivered therapies for cultural and identity considerations Scheduled coaching calls with reminders Monetary reward for completed questionnaires at each data collection time point Self-paced online modules with support coaches

|

| 11 | Urizar et al., 2019 [39] | Cognitive behavioral stress management framework In-person group-based intervention with interactive class activities Occurred at local prenatal clinics for better access to care Classes offered in both Spanish and English Use of focus groups for intervention feedback Address commonly reported stressors during pregnancy

|

| 12 | Zhang et al., 2025 [40] | Integration of technology Focus on patient-centered outcomes Scheduled postpartum follow-up visits Early behavioral health screening Sharing of study findings with the community and patient advisory groups to facilitate community engagement Dissemination of study findings through peer-reviewed publications, conferences, and presentations to health care policy committees

|

Table 3.

Recommendations and future directions.

Table 3.

Recommendations and future directions.

| Article # | Primary

Author/Year | Lessons Learned and Recommendations to Inform Future Evidence-Based Strategies and Interventions to Mental Health Interventions and Strategies to Increase Accessibility to Mental Health Treatment in High-Risk Pregnant and Postpartum Women | Major Themes Common

Across Included Studies |

|---|

| 1 | Baggett et al., 2021 [21] | Inclusion criteria limited study population to only speak English, non-English speaking populations should be studied Data regarding the pandemic’s effect of progression through intervention was not available to study. Engagement in the interventions, including pandemic effects on attrition, dosage or adherence, time to complete, or relatedly mobile coach behavior and fidelity await further study

| The main barriers to mental health care as pregnant or postpartum women were due to a lack of access to mental health professionals and geographic barriers (living in a rural area) The most successful interventions used mindfulness frameworks throughout the interventions Many successful interventions used telemedicine, which overcame many barriers that pregnant and postpartum patients encountered such as a lack of transportation to appointments, a lack of childcare to go to appointments, or a lack of mental health professionals available locally due to geographic location Other successful interventions used digital aspects such as online tools or text messages which patients enjoyed due to the asynchronous aspect of those tools Perinatal depression and anxiety were the most common mood and anxiety disorders observed throughout the studies Many of the interventions involving substance use disorders encountered problems with stigmas around substance use disorder when pregnant or postpartum or anxiety about involving child protective services Mental health needs that were unmet were more likely to be reported among non-Hispanic Black women and in comparison to non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women Many successful interventions were culturally adapted to the community and showed higher rates of approval and engagement among the participants Pregnant and postpartum women with little to no social support showed higher rates of depression and were more likely to interact with the providers of the intervention suggesting a substitute for missing social support Digital literacy and a lack of access to digital services did prove to be a challenge and barrier for some patients Mental health services that were associated with the perinatal care clinic had better adherence to care due to ease of using services and proximity to care already being received Greater adherence to the intervention by the health care workers was linked to greater participant outcomes although some health care workers struggled to find work–life balance during the intervention More longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes and a greater focus on biases and stigmas surrounding mental health should be looked into going forward

|

| 2 | Bhat et al., 2018 [22] | Future research should evaluate the impact of hybrid systems by combining the automated sending of personalized messages to patients with the care manager’s ability to respond to specific questions or requests from patients There is a need for clear guidelines for text messaging when it comes to breaches of data, extent of use, and use in emergency situations

|

| 3 | Bryant et al., 2023 [23] | Future studies should look at the impact of mobile health platforms on medical complications, such as cardiovascular disease and hypertensive disorders Future interventions developed to address postpartum health of underserved women should consider the influence of system and social variables when developing digital or community-based programs Conducting formative research at the start of a study can greatly inform the development of interventions for impacted populations as was carried out with Joyuus

|

| 5 | Evans et al., 2017 [24] | Because the data was taken from the nurses’ perspective, written records, interviews, or focus group data displaying the patients’ perspectives would be needed Future studies must continue to support the study and evaluation of nurse-led treatment strategies for antepartum depression

|

| 6 | Guille et al., 2022 [25] | Future studies should gather feedback from women who declined telemedicine services and understand the reasons why they did not engage in this treatment Qualitative research could offer a better understanding of care experiences and improve the validity of findings Larger longitudinal studies should identify potential benefits of telemedicine for perinatal women

|

| 7 | Hanson et al., 2023 [26] | Future research is recommended with a longitudinal approach to understand how individuals’ perceptions and experience in seeking mental health care evolve over time More research to address issues raised by the participants such as bias, stigma, isolation, and provider support is warranted

|

| 8 | Harris et al., 2025 [27] | Further studies are needed to collect intersectional data, including gender identity, race, and ethnicity, of pregnant and postpartum individuals with OUD, to better characterize pregnant and postpartum women’s needs as well as the equity gaps Future research should explore the barriers to implementing PPW-focused overdose prevention and develop targeted approaches to increase their adoption across diverse communities

|

| 9 | Hughes et al., 2023 [28] | The results cannot be applied beyond this sample due to the sample being predominantly White. Further studies should investigate more diverse practices and other geographic areas Future studies should also look into a longer time frame as this study only focused on the 8-week time frame for screening

|

| 10 | Jeanne Ruiz et al., 2019 [29] | |

| 11 | Jesse et al., 2015 [30] | Hispanic women were underrepresented in this study so another study should be conducted to determine feasibility among the Hispanic population A future study should be conducted that includes a larger sample as this study enrolled only rural low-income and minority women at risk for depression, so the results cannot be generalized

|

| 12 | Lewis et al., 2024 [31] | Future studies should assess challenges and lived experiences among low-income pregnant and postpartum women to better understand how these factors impact the efficacy of physical activity interventions Future studies should examine community-based physical activity interventions that improve social support among low-income pregnant and postpartum women

|

| 13 | Lord & Rao., 2025 [32] | Future research should assess the meditation videos used with a larger sample to see if the results can be generalized and effective in other populations Future research is needed to evaluate the range of digital implementation strategies (e.g., smartphone apps, text messaging, email) that can be used to deliver effective mindfulness interventions

|

| 14 | Mckimmy et al., 2023 [33] | Use lay mental health workers to aid in the efficacy and impact of mental health interventions Allow peer mentors to form relationships with patients built on trust and shared experiences Utilize domestic, intimate spaces for mentors to promote healing Provide adequate training for peer mentors Ensure flexibility in the delivery of mental health services in terms of location and scheduling Design culturally adapted mental health care interventions to address stigma and community values

|

| 16 | Rodriguez at al., 2021 [35] | Co-locate mental health services with prenatal clinics Postpartum mental health care should focus on women who experienced adverse neonatal outcomes Recognize the fourth trimester as a critical period for evaluation of maternal well-being and postpartum depression Psychiatric referrals should be timely and integrated into patient visits with providers

|

| 17 | Siegel et al., 2023 [36] | Combine community resources, direct relief, and behavioral health support to address disparities in access to mental health care Use bilingual community health workers and certified telephone interpreters to reach diverse patient populations Increase communication of mental health care provider and patient with multiple touchpoints

|

| 18 | Solness et al., 2020 [37] | Use a cognitive behavioral model of treatment for postpartum depression focused on behavioral activation and automatic thoughts Implement interactive web-based interventions for postpartum depression Use personal coaches to support patients with weekly coaching calls as they move along the online sessions Stigma continues to be a persistent barrier to mental health care and should be addressed in care plans

|

| 20 | Urizar et al., 2019 [39] | Use a group-based, cognitive behavioral stress management intervention to teach coping and relaxation skills Use bilingual classes to address language barriers in mental health care delivery Provide training for intervention facilitators to adhere to intervention content and provide quality instruction to patients Provide practical cognitive behavioral stress management skills and monitor patient use of skills in real-world settings

|

| 21 | Zhang et al., 2025 [40] | Integrate telemedicine into health care to increase access to postpartum mental health services Adapt existing health care infrastructure into a virtual context Incorporate feedback from patients, providers, and community stakeholders to adjust mental health service interventions

|

2.5. CASP Checklist

The CASP checklist was applied to transparently appraise original research studies by providing a framework to access the credibility, relevance, strengths, and limitations of the results (

Supplementary Table S2) [

41]. Coauthor KE evaluated the rigor and quality of the studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist, which has been utilized by previous scoping reviews [

41]. The CASP checklist implemented in this scoping review encompasses the following criteria: (1) clarity of stated study aims and objectives, (2) appropriateness of study design, (3) adequate description of the methodology and subject selection, (4) potential bias in sample selection, (5) representativeness of the sample for generalizability of study results, (6) use of statistical power analysis for sample size calculation, (7) response rate, (8) use of reliable and valid measures, (9) examination for statistical significance, and (10) inclusion of confidence intervals (CIs) in study findings [

41]. The response to each criterion was classified as “Yes”, “No”, or “Unsure”, and a quality score for each study was derived by summing the number of “Yes” responses [

41]. For item 4, “Selection Bias”, the reverse score “No” was counted within the rigor indices that contributed to the overall quality score of each included study [

41]. The CASP checklist findings are presented in

Supplementary Table S2.

3. Results

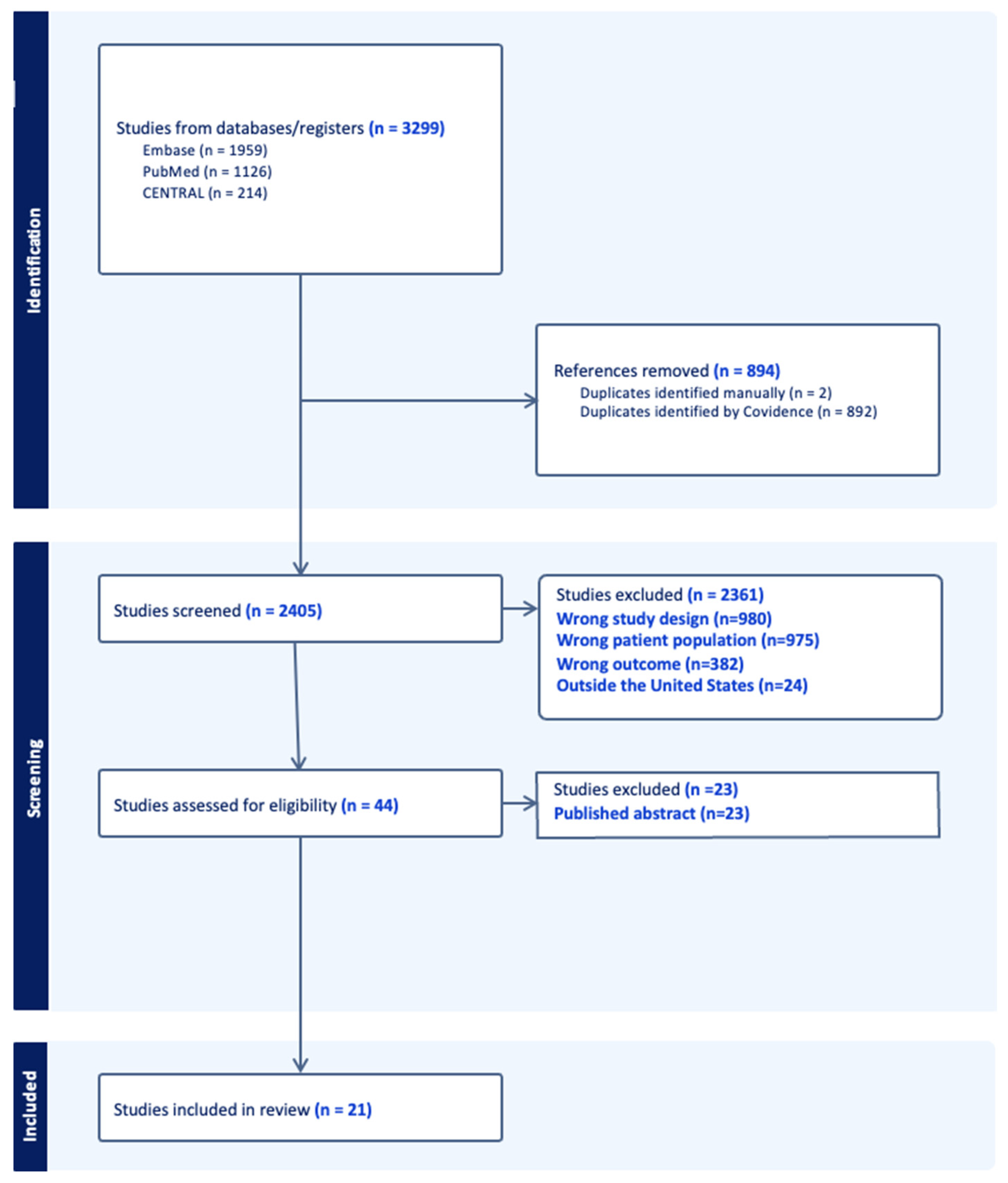

The initial study extraction resulted in 3299 articles from Embase (

n = 1959), PubMed (

n = 1126), and CENTRAL (

n = 214). Studies were then excluded due to duplications (

n = 894), leaving 2405 articles to be screened. During the screening process, a total of 2361 articles were excluded due to being the wrong study design (

n = 980), having the wrong patient population (

n = 975), having the wrong outcome (

n = 382), and being conducted outside the United States (

n = 24). An amount of 44 studies were left and assessed for eligibility, in which more studies were excluded due to being published abstracts (

n = 23). A total of 21 studies were included for analysis (

Figure 1).

The 21 studies retained for analysis were published between 2015 and 2025. Study designs included randomized control trial study (

n = 4); pilot study (

n = 3); mixed methods study (

n = 3); retrospective cohort study (

n = 2); qualitative study (

n = 2); prospective cohort study (

n = 1); descriptive study (

n = 1); quality improvement study (

n = 1); program evaluation study (

n = 1); process evaluation study (

n = 1); and cross-sectional study (

n = 1). Sample size ranged from

n = 7 to

n = 25,425 women. Collectively, the studies looked at pregnant women (

n = 5), postpartum women (

n = 4), or both (

n = 10) (

Supplementary Table S1).

3.1. Type of SDOH Explored Influencing Mental Health Outcomes in Pregnant and Postpartum Women

An examination of SDOH influential factors of mental health in pregnant and postpartum women was conducted, focusing on their classification into the Healthy People 2030 categories [

19]. Of the various SDOH identified, those related to neighborhood and built environment had the highest rates (

Supplementary Table S1). Specifically, transportation (

n = 5), social support (

n = 2), housing instability (

n = 2), geographic location (

n = 2), and marital status (

n = 1) were among the key elements of this Healthy People 2030 domain. Economic stability was seen to be a significant domain throughout the articles, with subcategories of income (

n = 7), economic barriers (

n = 5), employment (

n = 3), and food insecurity (

n = 1). Education access and quality also emerged as a recurrent domain, with subcategories of education level (

n = 7), health literacy (

n = 3) and language (

n = 2). Additional categories including social and community context (subcategories of race/ethnicity (

n = 16), discrimination (

n = 3), and veteran status (

n = 1)) emerged as a domain as well as health care access and quality (subcategories health care access (

n = 10) and insurance status (

n = 2)). Among the Healthy People 2030 categories, neighborhood and built environment emerged as the most prevalent, and among the specific SDOH, race/ethnicity was the most prevalent.

3.2. Reported Mental Health Outcomes in Pregnant and Postpartum Women

Reported mental health outcomes in pregnant and postpartum women were analyzed across the 21 studies. In regard to anxiety and depression among pregnant women, it was found that there was overall improvement in feelings of depression from the beginning to the end of pregnancy [

23,

24]. After formal screening, both pregnant and postpartum women had an increase in identification of mood disorders [

28]. For treatment of anxiety and depression in pregnant and postpartum women, the cognitive behavioral model significantly reduced EPDS scores, meditation videos significantly reduced perceived stress scores, and the CBSM intervention showed significant reductions in stress levels [

30,

32,

37,

39]. Stigmatization of substance use disorder among both pregnant and postpartum women was also identified and as a result it was found that in addition to women being reluctant to disclose their opioid use disorder (OUD), prenatal care providers were also reluctant to provide OUD services [

25,

26,

27].

3.3. Major Findings

Major findings across the studies focused on factors of flexible, patient-centered care. Findings by Evans et al., 2017, suggested that there was important evidence that therapeutic relationships can be developed with pregnant women who are depressed [

24]. By creating relationships in addition to increasing the flexibility of which care is available, pregnant and postpartum women can greatly benefit. Similarly, studies focusing on telehealth interventions showed improved access to perinatal care specifically for women living in rural areas [

25,

26]. In addition to telemedicine, the cognitive behavioral intervention reduced depressive symptoms for African American women at high risk for antepartum depression and for the full sample of women at low–moderate risk for antepartum depression [

30]. Meditation videos, prenatal CBSM, and physical activity may also aid in decreasing stress levels in this population of pregnant and postpartum women [

31,

32,

39]. Independent of the method, multiple studies highlighted the importance that the interventions for mental health are patient-centered, which facilitates trusting and effective connections between both peers and providers [

33,

40].

3.4. Barriers Experienced by US Underserved and Rural Maternal Populations in Accessing Mental Health Care Classified Based on the Socioecological Model

An examination of the barriers experienced by US underserved and rural maternal populations based on the five levels of the socioecological model was conducted. Across the barriers that were identified, individual barriers exhibited the highest frequency (n = 107), followed by community (n = 78), organizational (n = 76), interpersonal (n = 30), and policy (n = 28) levels. The barriers were also categorized based on thematic categories that were common across all studies included. The most common themes included language barriers, cultural barriers, and stigma-related challenges (n = 28); financial and childcare challenges (n = 24); geographic and transportation challenges (n = 22); limited health care accessibility, affordability, and quality (n = 14); inadequate patient education regarding health conditions, symptom management and treatment (n = 12); racism and discrimination (n = 12); and structural and regulatory challenges in health care settings (n = 11). Less frequently reported themes are distrust in medical institutions/health care system (n = 9); communication and health literacy challenges (n = 7); digital access and literacy (n = 5); COVID-19 (n = 4); and social norms and family-related issues (n = 4).

3.5. Evidence-Based Strategies and Interventions That Exist to Address Disparities in Accessing Mental Health Services Pre, Post, and During Delivery

Twelve out of twenty-one of the included studies were either experimental or interventional in nature and encompassed evidence-based strategies in the dissemination, implementation, and sustainability of intervention components. Interventions contained multiple different delivery models to address disparities in access to maternal mental health services during pregnancy and postpartum. Approaches that utilized technology included an adaptable mobile platform that met accessibility disparities, culturally diverse online tools, scheduled coaching calls, online modules, text messaging systems, early screening, and integration of technology into provider visits [

18,

28,

31,

32,

33]. These tools served as resources for parents and aimed to reduce logistical barriers to patient–provider communication and satisfaction. Cognitive behavioral interventions are also used and appear in both individual and group settings, tailored to the patients and centered on goals of managing stress, increasing self-efficacy, and utilizing social support [

19,

21,

27,

33]. Community and culturally based interventions included classes offered in multiple languages, community care managers, culturally competent care frameworks, and programs created by community health workers [

21,

22,

23,

26,

31]. Each of the studies highlight adaptable patient solutions that aid in building strong relationships with health care professionals, vital for increasing access to mental health care in underserved communities.

3.6. CASP Checklist Findings

All of the studies in this review discussed the study aims, the study design, and selection methods of the subjects. Valid measures were utilized in 100% (

n = 20) of the studies. When explaining the statistical analysis of the studies, only 40% (

n = 8) had or stated statistical power, and 60% (

n = 12) stated response rate. Additionally, when providing the results, 75% (

n = 15) of studies stated statistical significance and 25% (

n = 5) stated confidence intervals. In discussing results, only 45% (

n = 9) of the studies exhibited selection bias, although 35% (

n = 7) of studies confirmed randomization and no selection bias of the study. Many of the studies had very small sample sizes due to the qualitative nature of the study or due to the fact that they were focusing on a specific population. An amount of 10% (

n = 2) of the studies were considered to be generalizable. Overall, the quality scores of the studies all ranged from 4 (

n = 2, 10%) to 9 (

n = 1, 5%) out of 10. A total of 10% (

n = 2) of studies had a score of 5, 30% (

n = 6) of studies had a score of 6, 30% (

n = 6) of studies had a score of 7, and 15% (

n = 3) had a score of 8. Studies with a quality score of 6 or 7, 60% of the studies in this review, indicate a quality score of moderate rigor (

Supplementary Table S2).

3.7. Recommendations and Future Directions

Major themes consistently emerged across studies exploring disparities in accessing mental health services among pregnant and postpartum women [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Perinatal depression and anxiety were the most frequently identified mood and anxiety disorders. However, numerous barriers were reported that prevented these mental health care needs from being met. Among these barriers were the shortage of mental health professionals and geographic differences, particularly affecting women in rural areas [

25,

26,

38]. Non-Hispanic Black pregnant women also reported higher unmet mental health needs compared to non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women [

38]. Additional barriers included lack of transportation, lack of childcare support, experiencing homelessness, fear of judgment, and stigma, especially for women with substance use disorder [

26,

27]. Interventions effectively addressing these barriers often incorporated telemedicine, online platforms, and text messaging. However, digital literacy and lack of access to digital services appeared as significant barriers [

38]. Furthermore, care managers responding via text messaging faced challenges maintaining work–life balance [

22]. Other successful approaches emphasized mindfulness frameworks, culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions, and co-locating mental health and perinatal care services. Future recommendations from the studies emphasize the importance of conducting longitudinal research with larger and more diverse sample sizes. There is also a need to actively address biases and stigma surrounding mental health through culturally adapted and linguistically tailored interventions. Finally, greater consideration of the diverse needs of target populations in designing future interventions is essential.

4. Discussion

Our scoping review identified barriers affecting access to mental health services and the role of social determinants of health in exacerbating such challenges in US pregnant and postpartum women. Additionally, maternal morbidity and mortality outcomes and the scope of existing evidence-based interventions and implementation and dissemination strategies that were established to increase accessibility to mental health treatment in pregnant and postpartum women of high risk were also explored. Findings from this scoping review will address the gap in affordability and accessibility of mental health services in US pregnant and postpartum women residing in underserved communities [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Based on our review, most cited barriers encountered by pregnant and postpartum women were reported to be at the individual level of the SEM (

n = 107), and most common barrier theme categories included language barriers, cultural barriers, and stigma-related challenges (

n = 28); financial and childcare challenges (

n = 24); geographic and transportation challenges (

n = 22); limited health care accessibility, affordability, and quality (

n = 14); and inadequate patient education regarding health conditions, symptom management and treatment (

n = 12), among others. Such multilevel factors have been identified in prior studies and restrict women from seeking out or continuing mental health care during pregnancy and the postpartum period [

46]. At the individual level, patient beliefs about mental health, fear of judgment, and stigma remain persistent obstacles. Stigma associated with perinatal depression and anxiety can prevent women from acknowledging their symptoms and seeking out professional help [

47]. Studies have also explored the use of cognitive behavioral therapy and stress management frameworks to address individual-level barriers, and have found success with addressing depression, dysfunctional automatic thoughts, stress, and lowering cortisol levels in prenatal and postpartum women [

37,

39]. Financial instability is another prevalent barrier to accessing health care among maternal populations. Taylor et al. stratified the prevalence of financial hardships among peripartum women within three categories: unmet health care needs, health care unaffordability, and financial stress. From 2013 to 2018, the results displayed 24.2% of peripartum women reported unmet health care needs, 60% reported health care unaffordability, and 54% reported financial stress [

48]. This triad of financial hardship exacerbates disparities in mental health care at both the individual and policy levels of the socioecological model.

At the interpersonal level, health care practitioners may reinforce the gap between perinatal women and mental health care through inadequate training, lack of cultural sensitivity, and by holding stigmatized beliefs themselves [

47]. These characteristics can lead to misdiagnosis or undertreatment of maternal mental health conditions. Implementing task-sharing models along with training health care professionals in cultural competency can help mitigate these obstacles and improve the delivery of maternal mental health care [

33]. Geographic location and transportation challenges have also been reported as key barriers. Studies have found that pregnant women in rural areas face barriers in mental health care access, particularly in virtual and prescription-based care [

38]. This finding has been addressed in many studies that aim to implement flexible delivery services such as telemedicine, home-based programs, and co-location of health services. For example, the integration of mental health services within prenatal clinics has shown significant improvements in adherence to mental health referrals for women with postpartum depression [

35]. Moreover, challenges with interpersonal relationships can influence a woman’s likelihood of seeking and sustaining mental health care. Lack of social support from family members and partner relationships are barriers identified in the literature and highlight the critical need for supportive relationships during the perinatal period [

33,

49]. Exploring the impact of partner characteristics on maternal mental health has revealed emotional closeness, communication, and relationship satisfaction can contribute to the development of depression or anxiety among perinatal women [

50]. In addition, implementing lay mental health workers and peer mentors into mental health care aims to address these barriers by allowing patients to form relationships with peer mentors that are built on support and trust [

33].

Furthermore, at the organizational level, continuity of care, collaboration across services, and proper funding for perinatal mental health services are important characteristics of health care that must be addressed [

47]. Structural and regulatory challenges in health care settings are vast and include patient immigration status, insurance coverage, lack of provider availability, and prolonged wait times [

40]. These obstacles not only prevent the proper delivery of mental health care, but also contribute to inadequate patient education about mental health conditions and treatments, ultimately contributing to mistrust of the health care system among perinatal women [

48,

49,

50]. Some studies address these challenges by implementing community-based programs that utilize community health workers, multidisciplinary provider referrals, multiple touchpoints between patients and community health workers, and proper training of health care professionals [

50,

51].

Additional barriers at the policy level include immigration status, insurance coverage, health care costs, and employment challenges. These factors serve as significant sources of stress for perinatal women, making it more difficult for them to access mental health care [

47]. The dissemination of study findings to health care policy committees is crucial to systemic reform that addresses these barriers. Research can guide the development of policies that expand insurance coverage, fund mental health services, and improve employment protections for women [

40]. Policy-level change is essential for accessible and equitable mental health care for perinatal women regardless of socioeconomic status.

While our review revealed that individual-level factors remain the most frequently cited barriers to mental health care for maternal populations, effective solutions require coordinated interventions across community, organizational, and policy levels. Cultural beliefs, language barriers, stigma, and mistrust of the health care system create difficulties in accessing proper treatment and subsequently, cause adverse physical and mental health outcomes for both the mother and the child [

33]. Oftentimes, the accessible interventions for mental health treatment are not aligned with the cultural preferences of the patient, leading to a failure of addressing the root cause of distress and possibly alienating the patient. Consequently, culturally tailored interventions are essential to providing equitable mental health care for these communities. Evidence-based strategies such as telehealth expansion, integrated community health models, and culturally tailored programs have shown improvements in access to maternal mental health care and reducing disparities. Therefore, efforts to create change across all levels of the socioeconomic model are necessary to ensure that perinatal mental health care is comprehensive and responsive to the diverse needs of maternal populations.

Our results highlight the need for more evidence-based and theoretically oriented interventions to address mental health disorders and SUDs in this population. Patient-centered interventions were also recommended in multiple included studies due to their role in facilitating a more effective communication process between providers and pregnant and postpartum women. This finding aligns with the literature highlighting patient-centered maternity care as a major factor contributing to greater mental well-being and lower depression levels [

44]. Additionally, previous studies have emphasized the importance of a human-centered design for maternal care that greatly benefits and enhances the care that these women receive [

45]. Hence, patient involvement in decision-making regarding their mental health through culturally tailored and effective strategies addressing barriers to receiving needed mental health services is essential for longitudinal positive outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Culturally tailored interventions acknowledge the social determinants of health, lived experiences, and belief systems of diverse communities and adapt the provided care accordingly. Study results have shown that interventions that implement culturally trained providers, multilingual services, and task-sharing models—particularly those incorporating community health workers—lead to improved treatment adherence and outcomes. One such example is the Alma program, which uses trained Latina peer mentors to create a relationship with patients based on trust and shared lived experiences [

33]. Peer mentors are able to work with participants to self-monitor mood, schedule activities, solve problems, and serve as a bridge to formal professional mental health services when necessary [

33]. As demonstrated by the Alma initiative, community health workers and care managers are trusted members of the community and serve as a major role in connecting underserved women with the proper mental health services. Moreover, lay mental health providers also serve as consultants and co-designers of mental health treatment interventions using their cultural insight and experiences with patients. This cultural alignment of care with patient identity increases the likelihood that women will seek and adhere to care [

33].

In addition to cultural competence and culturally tailored strategies, sustained access to care and long-term follow up are vital characteristics of mental health care. Mothers are at a higher risk of developing mental health conditions during the perinatal period due to shifting physical and emotional demands. As a result, short-term interventions may not provide enough support for mothers as they experience these changes. Providing continuity of care into the postpartum stage has been associated with positive mental health in mothers and improved physical health in mothers and babies [

49,

50]. Evidence suggests that continuous engagement in care through scheduled follow-ups, regular screenings, and personalized care plans can improve the ability to identify perinatal women with depression and provide treatment recommendations [

51]. Improving mental health outcomes among underserved US pregnant and postpartum women requires sustainable support and care that is culturally tailored to the patient population with the help of community health workers and care managers. These strategies address individual and structural barriers that hinder access to mental health care while strengthening health care systems.