Moderate Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications Among Women in the Northern Borders Province, Saudi Arabia: Implications for Educational Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Participant Characteristics

2.2. Knowledge of GDM-Related Maternal Complications

2.3. Knowledge of GDM-Related Neonatal Complications

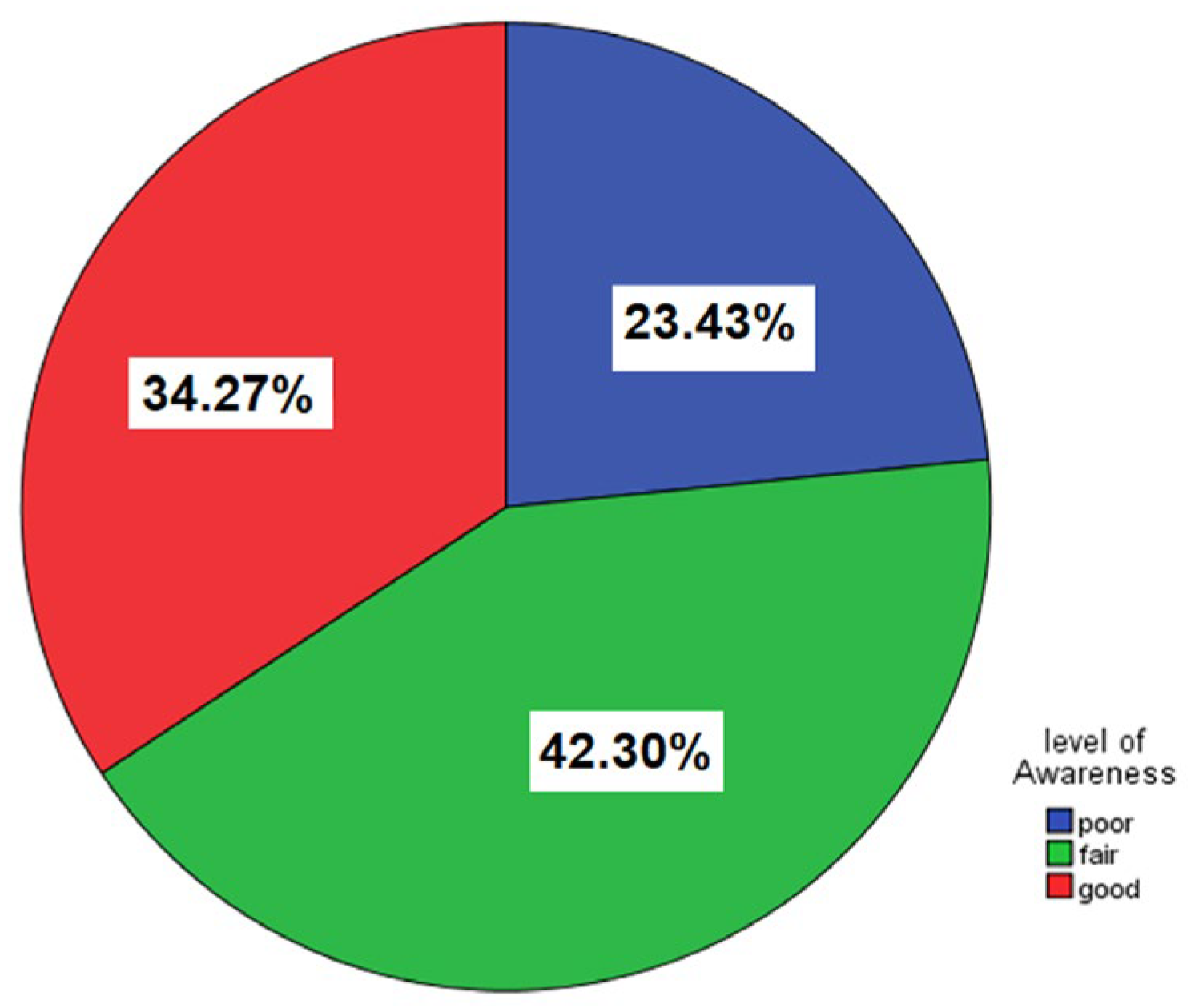

2.4. Overall Awareness Levels

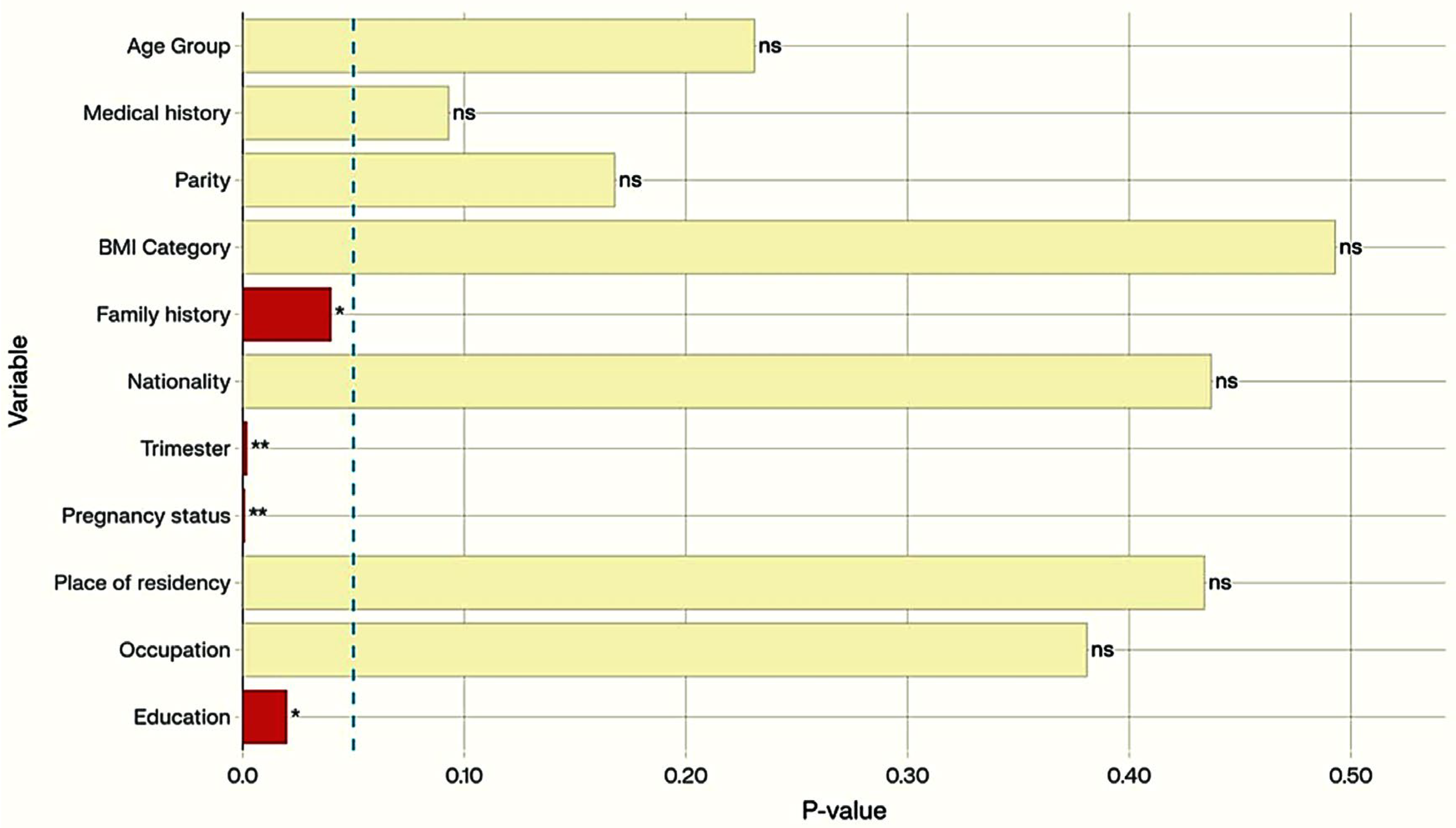

2.5. Factors Associated with GDM Awareness

3. Discussion

3.1. Key Findings

3.2. Comparison with Previous Studies in Saudi Arabia

| First Author (Year) | Region | Study Type | Sample Size | Main Outcome (Knowledge Assessment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alharthi (2018) [22] | National (Multiple) | Cross-sectional | 9002 | Most had fair knowledge, poor awareness of GDM diagnosis (15.9%). |

| Alnaeem (2019) [29] | Dhahran | Cross-sectional | 405 | There was a lack of GDM awareness among pregnant women, with limited knowledge of risk factors and inadequate self-care and management. |

| Abualsaud (2022) [19] | Jeddah | Cross-sectional | 385 | Nearly 77.8% had poor knowledge; 6.1% had good knowledge; main source: social media. |

| Khayat (2022) [25] | Almadinah | Cross-sectional | 333 | Nearly 53.5% have poor knowledge; 7.8% have good knowledge; rural women are at higher risk. |

| Wafa (2023) [23] | Tabuk | Cross-sectional | 539 | Nearly 76.1% had good knowledge; 70.9% understood the definition of GDM |

| Hakeem (2023) [30] | Jeddah | Cross-sectional | 489 | Of the participants, 53.6% exhibited comprehensive knowledge of GDM, 35.2% possessed moderate knowledge, and 11.2% displayed minimal knowledge. Elevated awareness levels were significantly correlated with higher education, increased gravidity, and prior knowledge of GDM. |

| Arafah (2024) [24] | Riyadh | Cross-sectional | 405 | More than 40% of the participants had poor knowledge about GDM complications, diagnosis, and management. Women with a lack of exercise, those having a history of GDM and primigravida, and those with a low education level were more likely to have poor knowledge about GDM. |

| Almazyad (2024) [17] | Qassim | Cross-sectional | 270 | Approximately 72.2% had poor knowledge, while 10% had good knowledge. |

| Present study (2025) | Northern Borders | Cross-sectional | 461 | Nearly 34.3% have good, 42.3% have fair, and 23.4% have poor knowledge; education and pregnancy status were associated with the knowledge levels. |

3.3. Clinical Implications and Future Perspectives

3.4. Reflections on Scope, Risks, and Educational Targeting

3.5. Strengths and Limitations

3.6. Study Implementation Challenges

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Setting

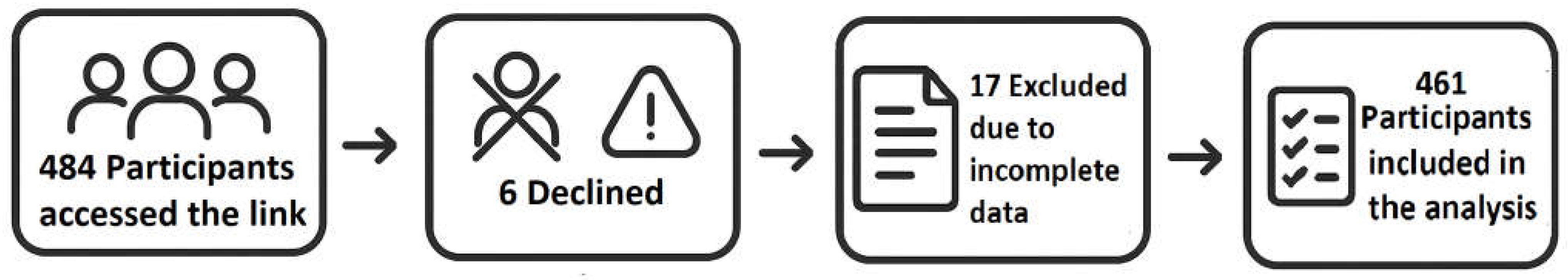

4.2. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

4.3. Sample Size Determination

4.4. Sampling Technique

4.5. Data Collection Tool

4.5.1. Questionnaire Development and Validation

4.5.2. Content and Face Validity

- The draft questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of three subject-matter experts (obstetrician, endocrinologist, epidemiologist) to ensure content validity, clarity, and cultural appropriateness. Based on expert feedback, and in response to concerns about participant comprehension, medical terms such as “polyhydramnios,” “oligohydramnios,” “dystocia,” “hyperbilirubinemia,” and “congenital anomalies” were replaced with simpler, locally familiar phrases (e.g., “too much or too little amniotic fluid,” “difficult labor,” “yellowing of the baby’s skin,” “birth defects”).

- A pilot test was conducted with 20 women from the target population, who were subsequently excluded from the main study.

- The questionnaire was distributed in Arabic, the native language of the study population. Technical medical terms identified by experts and highlighted by pilot testers were translated using lay terminology or brief explanations widely recognized by Saudi women in clinical settings. Comprehension of all questionnaire items by the Arabic-speaking population was confirmed during the pilot phase. Supplementary File S1 includes both the Arabic questionnaire as administered to participants and the English translation used for reporting purposes.

4.5.3. Reliability Assessment

4.5.4. Questionnaire Structure

- Sociodemographic Data: age, marital status, education, occupation, income, parity, gravidity, and family history of diabetes.

- Awareness and Sources of Information: questions assessing knowledge of GDM risk factors, screening, sources of information, and perceived impact on maternal health.

- Knowledge of GDM Complications: items evaluating understanding of GDM-related complications in mothers and newborns.

4.5.5. Outcome Measures

4.6. Data Collection Procedure

4.7. Consideration of Societal Structure

4.8. Statistical Analysis

4.9. Ethical Considerations

4.10. Quality Control

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Modzelewski, R.; Stefanowicz-Rutkowska, M.M.; Matuszewski, W.; Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E.M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus-Recent Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakshine, V.S.; Jogdand, S.D. A Comprehensive Review of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Impacts on Maternal Health, Fetal Development, Childhood Outcomes, and Long-Term Treatment Strategies. Cureus 2023, 15, e47500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeting, A.; Wong, J.; Murphy, H.R.; Ross, G.P. A Clinical Update on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 2022, 43, 763–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plows, J.F.; Stanley, J.L.; Baker, P.N.; Reynolds, C.M.; Vickers, M.H. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyce, B.L.; Dolinsky, V.W. Maternal β-Cell Adaptations in Pregnancy and Placental Signalling: Implications for Gestational Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.; Fagier, Y.; Ahmed, B.; Konje, J.C. An overview of diabetes mellitus in pregnant women with obesity. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 93, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadhli, E.M.; Osman, E.N.; Basri, T.H.; Mansuri, N.S.; Youssef, M.H.; Assaaedi, S.A.; Aljohani, B.A. Gestational diabetes among Saudi women: Prevalence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Ann. Saudi Med. 2015, 35, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahabi, H.; Fayed, A.; Esmaeil, S.; Mamdouh, H.; Kotb, R. Prevalence and Complications of Pregestational and Gestational Diabetes in Saudi Women: Analysis from Riyadh Mother and Baby Cohort Study (RAHMA). BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6878263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi, S.A.; Altalhi, A.A.; Nabrawi, M.F.; Aldainy, A.A.; Wali, R.M. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus among pregnant patients visiting National Guard primary health care centers in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduayji, M.M.; Selim, M. Risk Factors of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Among Women Attending an Antenatal Care Clinic in Prince Sultan Military Medical City (PSMMC), Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Case-Control Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e44200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Malhotra, A. Gestational diabetes and the neonate: Challenges and solutions. Res. Rep. Neonatol. 2015, 5, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryan, D.K.; Haddow, L.; Ramaesh, A.; Kelly, R.; Johns, E.C.; Denison, F.C.; Dover, A.R.; Reynolds, R.M. Early screening and treatment of gestational diabetes in high-risk women improves maternal and neonatal outcomes: A retrospective clinical audit. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 144, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, A.A.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Gestational diabetes mellitus—A metabolic and reproductive disorder. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bekai, E.; Beaini, C.E.; Kalout, K.; Safieddine, O.; Semaan, S.; Sahyoun, F.; Ghadieh, H.E.; Azar, S.; Kanaan, A.; Harb, F. The Hidden Impact of Gestational Diabetes: Unveiling Offspring Complications and Long-Term Effects. Life 2025, 15, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, J.K.; Deepthi Kondamuri, S.; Samal, S.; Sen, M. Knowledge of gestational diabetes mellitus among pregnant women in a semiurban hospital—A cross -sectional study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresima, P.; Visconti, F.; Interlandi, F.; Puccio, L.; Caroleo, P.; Amendola, G.; Morelli, M.; Venturella, R.; Di Carlo, C. Awareness of gestational diabetes mellitus foetal-maternal risks: An Italian cohort study on pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021, 21, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazyad, N.S.; Jahan, S. Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes Among Women Attending Primary Healthcare Centers in Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e59345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.M.; Keshk, E.A.; Almaqadi, O.M.; Alsawlihah, K.M.; Alzahrani, M.M.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Alsalhi, A.Y.; Alzahrani, S.M.; Alzahrani, J.A.; Alzahrani, M.A. Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Among Women in the Al-Baha Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e50163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualsaud, R.M.; Baghdadi, E.S.; Bukhari, A.A.; Katib, H.A. Awareness of gestational diabetes mellitus among females in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia—A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 3442–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akalpler, O.; Bagriacik, E. Education programs for gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2023, 33, 200195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeel, S.E.; Alsel, B.A.; Alrawili, N.F.; Alobidan, R.K.; Barghash, F.N.; Alanezi, H.H.; Alharbi, A.D.A.; Alharbi, T.D.A. Awareness of Diabetes Complications among Diabetes Patients in Northern Border Region in Saudi Arabia. J. Pioneer. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.S.; Althobaiti, K.A.; Alswat, K.A. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Knowledge Assessment among Saudi Women. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1522–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafa, M.H.; Ayoub, A.I.; Bukhari, T.A.; Amer Bugnah, A.A.; Alabawy, A.A.H.; Alsaiari, A.H.; Aljondi, H.M.; Alhusseini, S.H.; Alenazi, F.A.; Refai, H.M. Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Among Pregnant Women in Tabuk City, Saudi Arabia: An Exploratory Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e48151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafah, D.M.; Aldohaian, A.I.; Kazi, A.; Alquaiz, A.M. Factors Associated with Knowledge about Gestational Diabetes Mellitus among Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Nat. Sci. Med. 2024, 7, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, A.A.; Fallatah, N. Knowledge of gestational diabetes mellitus among Saudi women in a primary health care center of Almadinah Almunawarah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e22979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissassa, H.D.; Tufa, D.G.; Geleta, L.A.; Dabalo, Y.A.; Oyato, B.T. Knowledge on gestational diabetes mellitus and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics of North Shewa zone public hospitals, Oromia region, Central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Harrison, C.L.; Misso, M.; Hill, B.; Teede, H.J.; Mol, B.W.; Moran, L.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preconception lifestyle interventions on fertility, obstetric, fetal, anthropometric and metabolic outcomes in men and women. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 1925–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahmashi, H.; Maneze, D.; Molloy, L.; Salamonson, Y. Nurses’ adoption of diabetes clinical practice guidelines in primary care and the impacts on patient outcomes and safety: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 154, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaeem, L.S. Awareness of gestational diabetes among antenatal women at the King Fahd military medical complex hospital in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 75, 2784–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, R.; Alqerafi, A.; Malibari, W.; Allhybi, A.; Al Aslab, B.; Hafez, A.; Bin Sawad, M.; Almalky, N. Comprehension and Understanding of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Among Pregnant Women Attending Primary Health Care Facilities in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e46937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros Ruiz, M.; Perejón López, D.; Serna Arnaiz, C.; Siscart Viladegut, J.; Àngel Baldó, J.; Sol, J. Maternal and foetal complications of pregestational and gestational diabetes: A descriptive, retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhi, A.A.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Alyamin, M.M.; Hamdi, W.A.; Alyami, S.R.; Almagbool, A.S.; Almoqati, N.H.; Almoqati, S.H.; Al-Saaed, E.a.A.N.; Al Habes, H.S. Assessment of the knowledge of pregnant women regarding the effects of GDM on mothers and neonates at a Maternal and Children hospital in Najran, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 3, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuaim, M. The Composition of the Saudi Middle Class: A Preliminary Study; Gulf Research Center: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi, S.R.G.; Alanazi, H.W.H.; Alanazi, W.G.; Alanazi, N.S.Q.; Alenezi, D.O.B.; Al-Sweilem, M.; Alqattan, M.H.; Alanazi, I.L.N.; Tirksstani, J.M.; AlSarhan, R.S.; et al. Parents’ Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Pediatric Ophthalmic Disorders in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 902–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltom, E.H.; Alali, A.O.A.; Alanazi, R.K.M.; Alanazi, A.A.M.; Albalawi, M.A.A.; Alanazi, S.A.N.; Alanazi, M.S.G.; Badawy, A.A.; Mokhtar, N.; Fawzy, M.S. Exploring Awareness Levels of Diabetic Ketoacidosis Risk Among Patients with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, 2681–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Participants = 461 | No. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Age group (years) | Mean ± SD | 34.53 ± 9.96 | |

| 18 to 25 | 116 | 25.2 | |

| 26 to 35 | 135 | 29.3 | |

| 36–49 | 210 | 45.5 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Underweight | 11 | 2.4 |

| Normal weight | 158 | 34.3 | |

| Overweight | 151 | 32.8 | |

| Obese | 140 | 30.4 | |

| Nationality | Non-Saudi | 7 | 1.5 |

| Saudi | 454 | 98.5 | |

| Parity category | Nulligravida | 91 | 19.7 |

| Multigravida | 219 | 47.5 | |

| Grand gravida | 151 | 32.8 | |

| Are you pregnant | No | 413 | 89.6 |

| Yes | 48 | 10.4 | |

| Trimester (If pregnant) | First trimester | 23 | 5.0 |

| Second trimester | 20 | 4.3 | |

| Third trimester | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Medical history | Diabetes mellitus | 24 | 5.2 |

| Gestational diabetes milletus | 12 | 2.6 | |

| Hypertension | 18 | 3.9 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 25 | 5.4 | |

| Preeclampsia | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 12 | 2.6 | |

| None | 367 | 79.6 | |

| Family history | Diabetes mellitus | 122 | 26.5 |

| Gestational diabetes milletus | 11 | 2.4 | |

| Heart diseases | 6 | 1.3 | |

| Hypertension | 46 | 10.0 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 27 | 5.9 | |

| None | 249 | 54.0 | |

| Education | Preparatory or lower | 13 | 29 |

| Secondary school | 47 | 10.2 | |

| University | 381 | 82.6 | |

| Postgraduate | 20 | 4.3 | |

| Occupation | Employee | 221 | 47.9 |

| Housewife | 155 | 33.6 | |

| Student | 85 | 18.4 | |

| Place of residence | Arar | 365 | 79.2 |

| Al-Aweqila | 21 | 4.6 | |

| Turiaf | 20 | 4.3 | |

| Rafha | 16 | 3.5 | |

| Other areas of the Northern Borders Province | 39 | 8.5 | |

| Question | Yes | (%) | No | (%) | I Do Not Know | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of instrumental delivery? | 234 | 50.8 | 36 | 7.8 | 191 | 41.4 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of elective C-sections? | 234 | 50.8 | 36 | 7.8 | 191 | 41.4 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of emergency C-sections? | 324 | 70.3 | 26 | 5.6 | 111 | 24.1 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of preterm labor? | 318 | 69.0 | 32 | 6.9 | 111 | 24.1 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of inducing labor? | 209 | 45.3 | 54 | 11.7 | 198 | 43.0 |

| Do you think GDM increases polyhydramnios? | 214 | 46.4 | 39 | 8.5 | 208 | 45.1 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of oligohydramnios? | 129 | 28.0 | 93 | 20.2 | 239 | 51.8 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of membrane rupture? | 136 | 29.5 | 72 | 15.6 | 253 | 54.9 |

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of placental abruption? | 155 | 33.6 | 55 | 11.9 | 251 | 54.4 |

| Do you think GDM increases preterm? | 240 | 52.1 | 38 | 8.2 | 183 | 39.7 |

| Do you think GDM increases post-partum hemorrhage? | 162 | 35.1 | 82 | 17.8 | 217 | 47.1 |

| Question | Yes | N % | No. | N % | I Don’t Know | N % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think GDM increases the risk of high birth weight | 269 | 58.4 | 59 | 12.8 | 133 | 28.9 |

| Do you think GDM increases low birth weight | 138 | 29.9 | 162 | 35.1 | 161 | 34.9 |

| Do you think GDM increases breech delivery | 111 | 24.1 | 76 | 16.5 | 274 | 59.4 |

| Do you think GDM increases shoulder dystocia | 200 | 43.4 | 57 | 12.4 | 204 | 44.3 |

| Do you think GDM increases hypoglycemia | 164 | 35.6 | 64 | 13.9 | 233 | 50.5 |

| Do you think GDM increases hyperbilirubinemia | 184 | 39.9 | 62 | 13.4 | 215 | 46.6 |

| Do you think GDM increases congenital anomalies | 147 | 31.9 | 72 | 15.6 | 242 | 52.5 |

| Do you think GDM increases NICU admission | 266 | 57.7 | 31 | 6.7 | 164 | 35.6 |

| Do you think GDM increases stillbirth | 186 | 40.3 | 56 | 12.1 | 219 | 47.5 |

| Do you think GDM increases neonatal death | 163 | 35.4 | 54 | 11.7 | 244 | 52.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alenezi, H.N.; Alanazi, F.K.; Bin Muhanna, A.; Softa, S.M.A.; AbuAlsel, B.; Bayomy, H.E.; Esmaeel, S.E.; Fawzy, M.S. Moderate Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications Among Women in the Northern Borders Province, Saudi Arabia: Implications for Educational Interventions. Women 2025, 5, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030029

Alenezi HN, Alanazi FK, Bin Muhanna A, Softa SMA, AbuAlsel B, Bayomy HE, Esmaeel SE, Fawzy MS. Moderate Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications Among Women in the Northern Borders Province, Saudi Arabia: Implications for Educational Interventions. Women. 2025; 5(3):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlenezi, Hind N., Fayez K. Alanazi, Alhanouf Bin Muhanna, Shadi Mohammed Ali Softa, Baraah AbuAlsel, Hanaa E. Bayomy, Safya E. Esmaeel, and Manal S. Fawzy. 2025. "Moderate Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications Among Women in the Northern Borders Province, Saudi Arabia: Implications for Educational Interventions" Women 5, no. 3: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030029

APA StyleAlenezi, H. N., Alanazi, F. K., Bin Muhanna, A., Softa, S. M. A., AbuAlsel, B., Bayomy, H. E., Esmaeel, S. E., & Fawzy, M. S. (2025). Moderate Awareness of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications Among Women in the Northern Borders Province, Saudi Arabia: Implications for Educational Interventions. Women, 5(3), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/women5030029