Abstract

The SCOBY (Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast) is a microbial consortium composed of a diverse range of bacteria and yeasts that coexist symbiotically. The most commonly identified microorganisms include Gluconobacter, Acetobacte, Saccharomyces and Zygosaccharomyces. Its primary objective is to utilize sucrose as a substrate. SCOBY requires specific conditions for its multiplication, such as temperature, pH, and a suitable carbon source. Through its microbial dynamics and proper management, this consortium develops functional properties that are beneficial to health. This microbial consortium has been the subject of numerous studies due to the wide range of benefits it can offer through fermentation-derived products. Among the most frequently mentioned are organic acids, phenolic compounds, and a high concentration of probiotics. Originally, the SCOBY was used as a started culture in the production of the beverage “Kombucha”. However, due to the growing public interest, its use has diversified into fruit-based, dairy-based, and cereal-based beverages. Furthermore, its application has expanded to unconventional substrates. Its potential uses in other fields, such as medicine, as well as its antimicrobial activity, should also be noted.

1. Introduction

Polysaccharides are macromolecular polymers and represent the most common form of carbohydrates found in nature. These compounds are produced by plants, algae, or microorganisms. The natural production of polysaccharides encompasses diverse physiological and biological functions they can perform. Microbial polysaccharides have been highlighted in recent years, produced by sugar residues that can be linear or branched by glycosidic linkages [1]. The fermentation process conducted by the microbial consortium of the SCOBY leads to the production of bacterial cellulose, which possesses noteworthy physicochemical properties, positioning it as a promising alternative material due to its biocompatibility and minimal environmental impact [2]. Microbial polysaccharides are considered non-traditional and have found utility in medicine, disease treatment, industrial processes, and the food industry [3]. In the fascinating world of fermentation, a biofilm of great interest emerges: the SCOBY. This entity has garnered significant curiosity, as it is responsible for the fermentation of beverages, particularly the well-known “kombucha,” in which a bacterial cellulose biofilm is formed, known as bionanocellulose. However, the SCOBY is much more than just a gelatinous mass; it constitutes a living and complex ecosystem, both in its physical and chemical composition.

One of the recent trends in microbial polysaccharide production is the use of SCOBY, originally known as the “tea fungus” [4]. As a result of the fermentation process, a biofilm known as bionanocellulose is formed [5].

Currently, there are reports on the characteristics of kombucha, the original beverage produced by the SCOBY [6], as well as on the use of various substrates for cellulose production, related regulations, and compositional aspects [7]. However, emerging trends call for a comprehensive review that integrates the most relevant findings regarding cellulose, which has become the focus of numerous recent studies. One of the latest trends in microbial polysaccharide production is the utilization of the SCOBY [8]. As a result of the fermentation process, a biofilm known as bacterial nanocellulose is formed [9]. Studies suggest that cellulose may outperform synthetic polymers due to its broad applicability and its excellent potential as a biodegradable material [9].

In this context, the SCOBY is composed of a wide diversity of microorganisms—including bacteria (Komagataeibacter, Acetobacter, Lactobacillus, Azotobacter) and yeasts (Saccharomyces, Brettanomyces, Zygosaccharomyces)—SCOBY exhibits a complex microbial dynamic that leads to the production of a wide variety of compounds due to intricate microbial interactions, which could be classified as a renewable biopolymer [10]. This fascinating aspect has garnered interest within the scientific community, particularly concerning optimal conditions for its proliferation. The production of this polysaccharide can be influenced by factors such as temperature, pH, and medium composition, which are crucial for SCOBY development and activity, ultimately determining the presence of bioactive compounds, antioxidants, fatty acids, and probiotics in the medium [8].

Some of the properties of these polymers are related to structural and storage functions. In the case of SCOBY, cellulose stores most of the bacteria and yeasts comprising this microbial consortium, providing physical structure and forming a barrier that separates the liquid medium from the environment, moderating oxygen passage [11].

The presence of polyphenols and other beneficial compounds has promoted the use of SCOBY as a medium for producing functional beverages due to its health-promoting properties. The various applications of SCOBY in the food industry and other sectors offer extensive opportunities for research and innovation [12]. Although its role in the food industry has been extensively studied, other fields have also shown interest in its diverse characteristics. Bacterial cellulose formed by multiple microorganisms is a linear exopolysaccharide that is non-synthetic, porous, and non-toxic. With superior properties such as high porosity, chemical purity, and greater malleability compared to plant cellulose, one of the main advantages of producing and processing this material is its purification process, which requires fewer chemical treatments, making it an environmentally friendly alternative due to its biodegradability [13].

The characteristics of this microbial polymer and its diverse industrial applications provide an alternative to synthetic polymers. Beyond its extensive use in the food industry, SCOBY has been the subject of research across various fields. It has been applied in efforts addressing environmental pollution [14], and the modification of cellulose for medical purposes is also a relevant objective, particularly for its use in drug delivery systems, wound dressings, functional matrices, and the replacement of biomaterials in the same domain [15]. Applications in the textile sector have also emerged, proposing it as a sustainable material with potential as a renewable and biodegradable source, thereby offering a possible substitute for conventional materials commonly used in fashion. However, challenges related to reproducibility, scalability, and quality have been identified as limitations in the use of bacterial cellulose [16]. The production of cellulose has been considered a circular utilization alternative, being both sustainable and cost-effective due to its development through fermentation of waste substrates [2]. Its application as a sustainable biomaterial has been associated with industrial models aimed at generating products with low environmental impact [17].

Unlike previous reviews, the present work focuses primarily on the characterization of SCOBY-derived cellulose, the key factors necessary for its optimal development, and critical considerations regarding its use. It also offers an integrated perspective on the structural composition of cellulose. Therefore, this review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of SCOBY applications, detailing its composition and presenting novel areas of application—ranging from combinations with various fruits and cereals to a brief discussion of its potential use in other industrial sectors. This study aims to summarize each SCOBY production factor and promote its use in future applications as a natural, environmentally sustainable, and cost-effective polysaccharide in multiple areas.

2. SCOBY

2.1. Origin of SCOBY

The origin of SCOBY was documented in ancient China, specifically in the northeastern region of Manchuria [18], where it was known as “tea fungus” or “Divine che” around 220 B.C. [10]. The term SCOBY was adopted by Len Porzio in 1990. Originally, SCOBY is a cellulose biofilm in its solid state [19], also referred to as a three-dimensional cellulose zoogleal stela [4]. In many definitions, the word “fungus” is found due to its resemblance to a superficial mold that forms in some liquid media containing yeasts, but it is commonly known as a tea fungus [4]. Other sources indicate that this is due to its similarity to the fruiting bodies of macroscopic fungi [20].

Its fermentation medium consists of sugary teas or infusions made with dried leaves or roots [21]. The growth of this biofilm begins with a layer where the growing culture changes the color of the medium to a more opaque, non-homogeneous liquid and may cause bubbles. Its appearance is that of a thin, floating biofilm; when removed from the liquid medium, it has a wet and rubbery texture, which can become even finer and rougher when dried [22].

2.2. Chemical Characteristics

2.2.1. Chemistry

Studies indicate that SCOBY has an O-H hydrogen bond group, which contributes to its ability to maintain a firm and compact structure. However, its exact molecular composition is not fully described. Various authors describe its content as comprising organic acids, cellulose, ethanol, and polyphenolic compounds [23].

2.2.2. Physicochemical Properties

Using the Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller (BET) method [23], a technique that determines specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size, the characteristics of the pores formed in cellulose were analyzed, which are primarily located in the amorphous regions. It is important to note that not all areas of the cellulose surface exhibit these features, as the crystalline region is more homogeneous. The average pore size was identified as 1.5979 nm, with a volume of 0.299 cc/g, indicating the presence of micropores. Using the same technique, the structure was also classified as mesoporous (with a specific surface area of 19.91 m2/g and an average pore size of 6.189 nm), suggesting a structural change depending on the stage of fermentation [24].

2.3. Microbial Dynamics

2.3.1. Role of Microorganisms in SCOBY and Utilization of Substrates

The SCOBY contains yeasts, lactic acid bacteria, acetic acid bacteria, and bifidobacteria [20]. Its variation is qualitative and quantitative depending on the previously mentioned factors. It has been erroneously referred to as Medusomyces gisevii, implying a single cellulose-producing bacterium, although the cellulose composition is actually made up of a wide variety of microorganisms, creating a symbiotic consortium [25]. To date, there are no reports of a standardized microbiota; instead, there are multiple records from around the world with varying concentrations [26]. It is important to note that the concentration of fungi and bacteria varies depending on the area of the SCOBY. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis demonstrated that the upper layer has the highest abundance of microorganisms [19]. This is due to the availability of nutrients as well as factors such as temperature and oxygen.

The microbiota of SCOBY is highly complex and diverse, and this variation can be attributed to geographical location, the medium used, substrate proportion, origin, latitude [27], or climate during fermentation [28]. Some SCOBYs are commercialized with information on their chemical composition and present microbiota, which better predict the outcome of fermentation products, unlike those without characterization [29]. The genus Gluconobacter is the most prevalent in the consortium, comprising 86–99%, depending on the medium, according to data obtained from rRNA sequence analysis [4]. Some of the microorganisms reported in SCOBY are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Microbial composition of SCOBY, dominant bacteria and yeasts.

The texture adopted by SCOBY is attributed to the presence of acetic acid bacteria responsible for cellulose production. The genus Komagataeibacter is associated with kombucha production and can be found in both its solid and liquid phases. In the solid phase, the “daughter” layer of SCOBY can appear in approximately 2 to 3 days [4]. This genus has been determined as the main contributor to cellulose production due to its concentration, which increases with generations. By the tenth generation, it can reach a presence of up to 70% [4]. The synthesis of cellulose begins with the transport of the carbon source, for which the process of iridin diphosphate-glucose synthesis occurs through glucose-6-phosphate and glucose-1-phosphate [3]. It is important to note that not only Komagataeibacter is responsible for cellulose production; the presence of genera such as Acetobacter, Gluconobacter, Rhizonium, Pseudomonas, and Sarcina has also been reported [36].

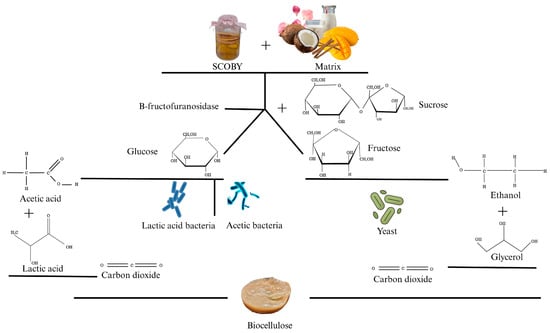

Regarding yeasts, their presence varies widely, and they have been identified in the solid phase [19] among the most described ones, where [4] mentions that those of the genera Saccharomyces and Zygosaccharomyces are most abundant. In the fermentation process, yeast carries out a hydrolysis process where it converts sucrose into glucose and fructose through the enzyme invertase (β-fructofuranosidase) [21]. They then proceed with ethanol production, utilizing fructose as a substrate (Figure 1) [13]. Delving into the action of yeast, hexokinase converts glucose into glucose-6-phosphate by adding a phosphate group and utilizing one ATP molecule. Subsequently, phosphohexose isomerase transforms glucose-6-phosphate into fructose-6-phosphate, then fructose-6-phosphate is converted into fructose-1,6-bisphosphate by the action of phosphofructokinase using another ATP molecule. Consequently, aldolase splits fructose-1,6-bisphosphate into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate, and finally, triose phosphate isomerase converts dihydroxyacetone phosphate into glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate [37]. The production of ethanol proceeds as follows: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate is converted into 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate by enzymatic action, acting as a cofactor NAD+ reduced to NADH. Subsequently, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate is converted into 3-phosphoglycerate, generating ATP as an energy source. The ethanol produced by yeasts serves as an essential substrate for acetic acid bacteria, which utilize it in their metabolic pathways [36]. Subsequently, 3-phosphoglycerate is converted into 2-phosphoglycerate, which in turn becomes phosphoenolpyruvate, eventually leading to pyruvate with the generation of more ATP. Through this process, yeast takes pyruvate and converts it into acetaldehyde, then to ethanol and carbon dioxide [37]. Overall, yeast contributes and participates throughout all the described processes [31].

Figure 1.

The metabolism of the symbiotic consortium of bacteria and yeast from sucrose.

On the other hand, bacteria such as Acetobacter sp. [13] oxidize ethanol, transforming glucose into acetic acid and gluconic acid (Figure 1). Enzymes such as dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase are involved in this process [17]. Yeasts operate in an anaerobic environment as they are concentrated on the surface of the medium, where there is insufficient oxygen, unlike acetic acid bacteria [37].

2.3.2. Metabolic Activity and Functional Products of SCOBY During Fermentation

In the process of action of bacteria and yeast, certain chemical components such as glucose, fructose derived from sucrose are produced [38]. During the transformation process of sucrose into ethanol, organic acids are produced, which are of paramount importance to the nutritional value of a food, also affecting its taste [39]. During the fermentation process, some of the most important organic acids produced are acetic, lactic, and phenolic acids, which, when present, act as a preventive barrier against contamination due to a pH of 3, within the 2.5–4.2 range that minimizes the risk of pathogenic bacterial proliferation [40].

The most common acids are acetic and lactic acids, followed by gluconic and glucuronic acids. The wide variety of these compounds is normal since malic, tartaric, succinic, oxalic, and pyruvic acids have also been reported [32]. Organic acids also aid in the preservation of the environment by reducing competition from unwanted fungi and bacteria for the same process [21].

In the case of gluconic acid production, higher concentrations have been reported when fermentation occurs under low sucrose conditions [41]. Fermentation through SCOBY generates ethanol; however, alcohol levels typically remain within a range of 0.5–1.2% v/v, mainly due to the action of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which also produce carbon dioxide during their reproduction. Ethanol, like organic acids, contributes to the inhibition of pathogenic bacteria, thereby enhancing microbial safety during fermentation [36,40].

The presence of bioactive compounds in kombucha-type beverages is one of their main attractions. High concentrations of polymeric polyphenols, specifically theaflavins and tearubigins, have been found in these fermented beverages. However, the variety of phenolic compounds is extensive, with cases reporting the identification of over 103 unreported compounds, depending on the food matrix used. Among the identified compounds, the majority belong to the flavonoid type, followed by phenolic compounds and phenolic acids [41]. Without forgetting the high concentration of antioxidants present in this fermentation, the concentration of these compounds can vary due to the diversity of phenolic compounds. These compounds have the ability to eliminate free radicals, including singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals [17]. Similarly, the antioxidant capacity of the fermentation is affected by the production of acids such as ascorbic and organic acids [41].

Not only are bioactive compounds present, but also water-soluble vitamins such as B1, B2, B6, B12, and fat-soluble vitamins like vitamins E, K, and A are produced [11]. Amino acids, biogenic amines, and pigments are also produced [17]. These vitamins support acetic bacteria in their metabolic processes. Minerals such as nickel, magnesium, iron, lead, zinc, chromium, copper, and zinc, like phenolic compounds, their presence depends on the symbiotic culture included and fermentation conditions [7]. Anions such as fluoride, bromide, iodide, phosphate, chloride, nitrate, or sulfate are also present [4].

Due to the metabolic activity of the symbiosis, hydrolytic enzymes are present [42]. The enzyme β-fructofuranosidase, responsible for hydrolyzing sucrose, is the most mentioned in the literature, but there are others with different functions, such as hexokinase, phosphohexose isomerase, phosphofructokinase, aldolase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase, phosphoglycerate mutase, enolase, pyruvate kinase, and pyruvate decarboxylase present in the fermentation process [37]. The enzymatic activity of fermentation is affected by the temperature at which the process occurs [43].

The biofilm is composed of microfibrils that are 100 times thinner than plant cellulose, tending to be thin and unbranched. Its function is to anchor and protect cells from unfavorable conditions such as ultraviolet radiation or high hydrostatic pressure, helping to maintain microorganisms in an aerobic environment for survival. Additionally, it exhibits high water absorption and mechanical strength [4], aiding in moisture retention and preventing dehydration [3]. Moreover, it possesses characteristics such as crystallinity, biocompatibility, high porosity, and no toxicity. The production of cellulose will be halted by the total consumption of nutrients in the medium or the accumulation of carbon dioxide (CO2) between the medium and the SCOBY [44].

2.4. Kombucha

This beverage was known as ‘Tea Kvass’ upon arrival in Russia by Orientals, which was then distributed in the European continent in the early century [10]. After the Second World War, this beverage gained popularity on a larger scale, expanding to countries like Germany, France, and Italy, using different names such as ‘tea fungus,’ ‘Kargasok Tea,’ ‘Manchu Fungus’ [3]. Nowadays, it is one of the fermented functional beverages with the highest growth. In 2019, it had a turnover of 1.67 billion dollars, which increased to 2.2 billion in 2020 with a growth outlook of 20% for the following years [3]. In 2023, the global market reported sales of 3318.1 million dollars, and it is estimated that by 2032, it will reach approximately 24,254.5 million dollargs [45].

The beverage of kombucha tea is considered an alcohol-free (or low alcohol) beverage [19], obtained from fermentation of green or black tea, with sugar as a substrate through a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, SCOBY [6]. The fermentation process takes place over a period of 7–10 days, during which a floating cellulose layer forms inside the medium. Due to the fermentation process, kombucha has a sour taste, attributed to its content of organic acids and the carbon dioxide produced by the same process [4].

The process of making Kombucha is very ancient and simple. It starts by preparing the tea, using 5 g of tea leaves in 1 L of water, brought to a boil for 10–15 min. Subsequently, it is filtered to remove impurities. The tea and 50 g of sucrose are then placed in a previously sterilized container and stirred until a homogeneous result is achieved. This mixture must achieve a pH of 4.6, so a percentage of a previously fermented beverage is added to it. Another function of this process is to reduce possible contamination by maintaining a low pH. Finally, 5–10% (v/v) of SCOBY is inoculated into the prepared liquid. To maintain an airflow without being exposed to the environment, a cotton cloth is placed, avoiding contamination, and regulating the flow of oxygen. To maintain airflow without exposure to the external environment, a cotton cloth is placed to prevent contamination and regulate oxygen flow. Fermentation is carried out at room temperature or in a controlled dark environment between 20 and 30 °C, a suboptimal yet acceptable temperature range [12].

After several days, a small cellulose layer, which is the “daughter” SCOBY, will start to form, typically within approximately 14 days depending on the conditions. The pH of the liquid decreases to 2.0 [12]. Kombuchas are made from tea, so the variety of microorganisms present, fermentation time, and produced metabolites can vary greatly depending on the type of tea, whether it is green or black, and the energy source [27]. This beverage is recommended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as safe for human consumption, and there is also a recommended dosage by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with a daily consumption dose of 110 mL of kombucha [46]. However, it is also mentioned that it can very rarely cause allergic reactions, leading to symptoms such as headaches and even vomiting.

The practice of second fermentation in kombucha has been reported, wherein the primary fermentation involves the production of the main compounds previously described. However, innovation has led to the implementation of a secondary fermentation step aimed at flavoring the kombucha through the addition of various fruit juices and/or herbs, thereby enhancing its taste profile [46]. This second fermentation typically lasts 2–3 days under conditions similar to those of the primary fermentation. However, it lacks the presence of cellulose and is carried out at reduced temperatures, down to 4 °C, due to refrigeration. The primary goal of this process is to increase CO2 production, thereby improving the beverage’s sensory attributes. It is important to note that this process merely slows down fermentation, as the microorganisms present may remain active [7]. This step can also be considered part of the storage process, as the kombucha can be bottled, creating anaerobic conditions that promote natural carbonation [47].

3. Uses Focused on Aliments

With the migration of SCOBY usage across continents, this consortium has been employed for various purposes with a variety of matrices or aims. In the case of food uses, substitutes for tea have been innovated, attributing different sensory and chemical characteristics, as well as an increase in their nutritional qualities suggesting they are healthy foods [18]. It has been considered a biomaterial with broad uses in the food industry and beyond due to its characteristics such as high chemical purity, as it has a high fiber content and is free of hemicellulose [36]. This cellulose is currently the fastest fermentation route in functional beverages [21].

3.1. Fruit-Based

A wide variety of fruits have been tested in kombucha-type fermentations, such as coconut, apple, grape, papaya, and strawberries [18], as well as banana and pomegranate [48]. The use of SCOBY with fruits as a substrate enhances the compounds present in the fruits themselves, such as polyphenolic compounds and antioxidants. In acidic fruits, the presence of inulin oligosaccharides and a bitter taste has been elevated [49].

A fermentation was carried out to enhance the functionality of phytonutrients from papaya (Carica papaya Linn.), including both pulp and leaves. This was achieved using strains of SCOBY selected from the MARDI Food Culture Collection. The preparation method involved a suspension with 5% papaya pulp and leaves, and a 10% inoculum of the microbial consortium (Dekkera sp. & Komagataiebacter sp.), under incubation conditions of 30 °C temperature, for a fermentation period of 4 days. This beverage demonstrated greater efficacy against drugs in the treatment of obesity in mice, which is attributed to its high acetic acid content [50], presenting it as a functional beverage for improving intestinal health, assisting in the prevention of obesity, and controlling body weight.

The effect of SCOBY on different matrices has been studied meticulously. In the case of [31], a fruit and three types of SCOBY were used, conducting three trials with different sources: one prepared in the same laboratory, the second provided from a local market, and the last from a store named “Oh My Kefir!”. In this study, tap water (80 °C) was combined with 12 g of dried strawberry tree fruit (Arbutus unedo), white sugar (70 g/L), and SCOBYs (40 g/L) previously obtained with 10% of the medium. The mixture was fermented at room temperature in darkness for a period of 21 days. The pH decreased to 3.9 and 3.2 throughout the fermentation process. The carbohydrate percentage decreased in the first 7 days, with a final percentage of 1.5% on day 21. The protein content remained low, ranging between 1.2 and 0.2 µg/mL. There was an increase of 1.6 to 2.5 times in the total phenolic content after fermentation.

The fermentation of kombuchas has led to the inclusion of flavorings, as in the case of [51], which included percentages of mango pulp. Treatments were conducted with 2.18 g of SCOBY, 5–10% starter medium, and 5–10% rosemary tea for the initial treatments, and 5% mango pulp for aroma treatments, with fermentation carried out for 8 days at room temperature (approximately 26–30 °C). It was reported that there was a reduction in sugar content except for the aroma treatments, a decrease in pH, ethanol production below 0.5%, making it not considered an alcoholic beverage, and a high content of phenolic compounds and tannins compared to those reported in rosemary tea and mango pulp alone. However, although fermentation is widely associated with the enhancement and release of phenolic compounds, it may also present certain drawbacks. Prolonged fermentation can lead to the accumulation of organic acids, potentially reducing the bioavailability of beneficial compounds [6]. Furthermore, advanced stages of fermentation may result in the transformation of polyphenols within the medium, as these compounds can be metabolized by bacteria or yeasts as part of their metabolic processes. This transformation may lead to a decrease in specific polyphenols, thereby also altering the antioxidant capacity of the final product [3].

3.2. Cereals

Originally, the primary source of nitrogen and minerals is black and green tea, which belong to the Camellia sinensis family [48]. In recent years, research has been conducted with different substrates, such as the use of seeds and grains, specifically germinated corn without the addition of sucrose. This resulted in a SCOBY classified as healthier, which had higher acceptance than traditional commercial kombucha fermentation.

Germinated corn was used with a prior treatment involving a mixture of 5% (w/v) sucrose and 1% (w/v) inoculum, along with a SCOBY (Kefiralia® obtained from Burumart Commerce S.L.), fermented at a temperature of 30 °C. This resulted in a decrease in pH from 4 to 3.8. Sensorial analysis yielded values above average, although when compared to a commercial product, the “odor” factor was the most overlooked. Hence, it is considered a viable option for formulating more fermented cereal-based beverages [52].

3.3. Beer

The combination of SCOBY with yeast such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fermentis [53] was utilized to produce beer using Pilsen Agraria-National malt from Guarapuava, Paraná, Brazil. In this process, 2.5 g of yeast were added, resulting in a population of 1.64 × 109 cells/mL, along with 12 g of SCOBY cellulose and 10 mL of the medium in which the cellulose developed, all added to 2 L of wort. For the fermentation process, 2 L of wort were taken, inoculated with the mentioned yeast and 5–10 mL of kombucha, and 6–12 g of cellulose, then fermented at 20 °C for 11 days, resulting in beer.

3.4. Dairy

The use of SCOBY for less common fermentations such as dairy beverages is becoming more common. Different authors [20] developed fermented beverages mentioning the use of a combination of 78% SCOBY, 10% kombucha tea, and 8% milk with and without lactose. Homogenization and pasteurization were carried out, and in the final production of the dairy beverages, 2.5–5% of the mentioned elements were used in a fermentation process at 42 °C for 8 h. As a result of this process, a 30% reduction in sugar content was achieved, as well as containing active microflora and organic acids.

Fermented milk samples with kombucha inoculum [54] began with 1.5 g/L of black tea, 10 g/L of sucrose, and 10% v/v of kombucha inoculum, at 25 °C for an initial fermentation period of 7 days. From this initial fermentation, 15–30 mL/L of the inoculum was taken, added, and homogenized with milk at a temperature of 43 °C for fermentation.

Fermentation was halted upon reaching a pH of 4.5. The inoculum elevated the total solids content, increased the energy value, and improved the texture of the dairy product. However, it did not reach a similar consistency to yogurt in static samples. In samples subjected to agitation, the product’s firmness was higher, likely due to medium oxygenation. Regarding sensory characteristics, the consistency improved, with better acceptance observed in samples subjected to agitation [55].

4. Functionality and Benefits of SCOBY Polysaccharides

Health Benefits

The exponential increase in the consumption of fermented beverages has driven studies related to different types of media or alternative microorganisms that can generate products like SCOBY [56]. In vitro studies explore the multiple beneficial activities and enzymatic function in the microbial dynamics present in cellulose [42]. Research has shown that the benefits resulting from this fermentation can vary depending on the substrate used, as well as the different characteristics that both the phytochemical and organoleptic content can acquire [42]. This is evident in the fermentation of fermented dairy products with a kombucha starter culture, which improved the sensory characteristics of the product, resulting in better acceptance compared to the control products [57].

It has been demonstrated that they are also a source of fatty acids present in the medium. Kombucha, being the original beverage that utilizes SCOBY, has more reports on changes in functionality in the beverage. It has been reported [12] that the polyphenol content increases during fermentation with SCOBY, from 299.6 mg GAE/L on day 7 to 320.1 mg GAE/L on day 14. However, standardization in fermentation time is recommended due to the variability that may occur. Polyphenols can eliminate free radicals as well as regulate blood sugar and fat oxidation [35].

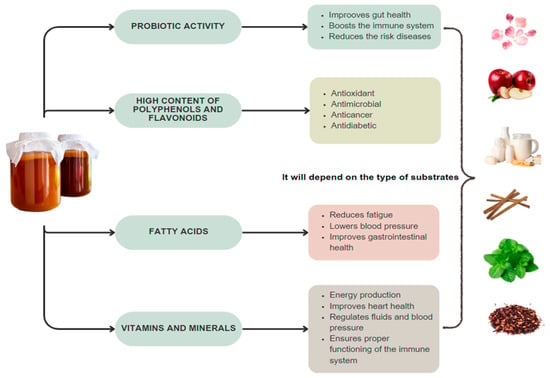

The presence of multiple compounds such as polyphenols or minerals in products fermented with SCOBY acquires various properties such as antioxidants, antimicrobials, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory, among others. This depends on the medium and the compounds that SCOBY will utilize for its fermentation [58]. Up to 127 phenolic compounds have been reported in fermentations [41]. Consumption of products fermented with SCOBY is considered a functional food due to the wide-ranging properties of polyphenolic compounds, which play a vital role in the human diet. Additionally, they are highly appreciated because they can also eliminate free radicals, thus reducing the risk of cancer. Tannins, phenolic acids, and flavonoids have been found in various fermentations and are considered dietary polyphenols, preventing cardiovascular diseases and obesity [59]. However, the variety and quantity of different molecules produced in fermentation will depend on the medium in which the symbiosis develops (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Compounds present in fermentation with SCOBY and their health benefits using different fermentation methods.

Fermentation results in the production of acetic acid as the main product of microbial dynamics, which helps reduce fatigue, blood pressure, and plays a role in improving gastrointestinal health [35]. Beverages fermented with SCOBY have demonstrated antioxidant activity, which helps counteract the number of free radicals [3]. Multiple studies have confirmed the presence of various vitamins, water-soluble sugars, amino acids, biogenic amines, proteins, hydrolytic enzymes, ethanol, carbon dioxide, polyphenols, and various minerals [4]. There are reports of the presence of D-saccharic-1,4-lactone (DSL), which inhibits the activity of glucuronidase. This enzyme can hydrolyze glucuronides, which are precursors of cancer [59]. This same author mentions that this product can be consumed by cancer patients to regulate their pH levels, as its pH is 7 or higher, without mentioning the contribution of lactic acid.

Despite various studies [3] supporting its functional activities and the activity of various compounds, experimental epidemiological studies have been conducted where consumption was offered to a child with and without trisomy 21. This aimed to determine its influence on the intestinal health of individuals. It was demonstrated that even with a short treatment time, the consistency of the stools of the children, especially the patient with trisomy 21, could be improved. These results are attributed to the probiotic content of kombucha. In vivo studies have demonstrated that one of the main benefits of SCOBY-derived microorganisms is their probiotic activity, which supports intestinal health, enhances the immune system, and reduces the risk of diseases associated with the disruption of beneficial microorganisms in the intestinal tract, where a deficiency of these microbes may result in a reduced capacity to produce short-chain fatty acids [60]. Despite multiple studies reporting the benefits of consuming these fermentations, further in vivo research is necessary to corroborate these effects.

In addition to its beneficial effects, there are warnings regarding its production due to potential adverse contaminations, primarily resulting from human error, such as poor hygiene practices and the use of inappropriate materials, including lead poisoning associated with unsuitable fermentation vessels. A biological risk involves foodborne pathogen contamination, including Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Clostridium botulinum, despite the low pH levels, as well as exposure to mycotoxins produced by molds such as Aspergillus spp. Furthermore, during the biotransformation processes occurring throughout fermentation, organic acids are released, which may lead to the accumulation of organic acids in the bloodstream (e.g., acetic and glucuronic acids). Such effects have only been reported in susceptible individuals, particularly those with underlying conditions such as acute renal failure, HIV infection, or pregnant women with hypersensitivity [61]. Excessive consumption of this beverage may result in hepatotoxicity, as well as interactions with pharmaceutical compounds. Gastrointestinal effects such as nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting have also been documented, although infrequently, and are typically associated with the ingestion of products exhibiting excessively low pH levels (<2.5) [6,62].

5. Factors Affecting Polysaccharide Synthesis

5.1. Conditions in the Fermentation Process

In contrast to factors such as temperature, fermentation time, initial medium concentration, and cellulose—which directly influence the metabolic activity of the SCOBY—one of the recommended conditions to prevent the degradation of bioactive compounds released during fermentation is the absence of light [31]. Although some authors suggest conducting the process under low or no light conditions, there are no studies supporting the necessity of maintaining the SCOBY in complete darkness without affecting its development [48].

5.2. Traditional Culture Medium

Due to its composition, SCOBY has been extensively studied as a source of cellulose. The cultivation of this microbial consortium is simple as it uses glass containers, including plastic trays, which are utilized as discontinuous small-scale reactors [4]. For its production, a medium containing 2% glucose, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, 0.115% citric acid, and 2% agar has been employed as a cultivation medium. Other media options include glucose yeast extract-calcium carbonate, Carr medium, Sabouraud Dextrose agar, or glucose–ethanol medium [48].

5.3. Alternative Culture Medium

SCOBY can be produced in the Hestrin–Schramm (HS) medium, a synthetic medium based on glucose, peptone, yeast extract, etc. However, sucrose is preferred as a substrate due to its higher production of gluconic acid, which can potentially hinder cellulose production. Additionally, sucrose is more economical than using glucose [44]. Uncommon ingredients have been used in some media, such as papaya leaves and fruit, used in a proportion of 10% (w/v) of leaf and pulp powder and 10% (w/v) sugar, inoculated with 20% (w/v) of the symbiotic culture at 24–37 °C under agitation [34]. The resulting beverage had an acceptable flavor due to its pH ranging from 2.5 to 3.12, with ethanol production transformed into acetic acid. As shown in Table 2, various culture media have been studied with different food matrices. 38 Media have been used to carry out processes such as the enumeration of bacteria and yeast present in the SCOBY, where a sample is extracted to obtain a suspension in peptone, and subsequently, potato dextrose agar (for yeast) and GYCA media (for bacteria) are used. The latter is supplemented with 30 g of glucose, 3 g of peptone, 10 g of CaCO3, 5 g of yeast extract, 95% ethanol, 20 g of agar, and distilled water to a total volume of 1 L.

Table 2.

Comprehensive analysis of SCOBY: matrix composition, fermentative variables, and phytochemical and functional effects.

5.4. Functional Improvements and Processing of SCOBY

One of the key requirements for the application of various materials is the ability to determine the yield obtained from a given process—in this case, from fermentation.

Cellulosic yield can be determined by starting with the removal of SCOBY from the inoculum and cleaning it repeatedly with distilled water, followed by drying at temperatures between 40 and 50 °C until a constant weight is achieved [36]. Performance data have been recorded where fermentation residues are first removed, excess liquid is dried, and its mass is measured to obtain the yield [13] using the following equation:

The cellulose yield relative to the sugar content can be obtained using the following formula [36]:

Cellulose productivity in relation to days:

Reports indicate an average yield of 55 g/L, with a productivity ranging from 1 to 5 g/L per day, depending on the conditions. Depending on the fermentation conditions, the yield may increase or decrease [44].

The properties of bacterial cellulose can be further enhanced to exploit its full potential by incorporating physical or chemical reinforcements, such as metals, nanomaterials, and antimicrobial compounds. These modifications can be achieved through techniques including amidation, acetylation, and carboxylation.

One of the methods to enhance certain characteristics of SCOBY is the use of reinforcements such as metals, nanomaterials, and antimicrobials, both physically and chemically, with methods such as amidation, acetylation, and carboxylation. Studies mention the use of materials such as apple powder mixed with glycerol, which acts as a uniform, homogeneous layer. Although the appearance obtained may be unappealing, the smell improves, as only the scent of apple is perceived. Nevertheless, its use is limited due to its permeability [26]. One of the best characteristics of SCOBY is its purity and ultrathin layers, which are 100 times smaller than those of plant cellulose, with higher polymerization and crystallinity, providing greater water absorption, adaptability, biocompatibility, and resistance, while also being biodegradable.

In terms of its use and optimization, it can be treated solely with alkalis. Cellulose has been successfully used as a material that can be treated with a pretreatment process [70], described as follows:

- (A)

- Washing: This step involves removing the culture medium and all microorganisms with 3% NaOH for 90 min at 25 °C and 70 rpm.

- (B)

- Neutralization: Residues from the first step are removed, washed with water, and the pH is adjusted to 3 with acetic acid, for 30 min at 70 rpm. Finally, it is washed again with distilled water.

- (C)

- Bleaching: With 5% H2O2 for 1 h at 90 °C under stirring at 120 rpm. It is then washed and placed in an 8% NaOH solution for 30 min in an ultrasound bath.

- (D)

- Conditioning: It is washed and immersed in acetic acid with a pH of 3 for 30 min at 70 rpm. Finally, it is washed with plenty of water until the pH reaches 7.

Other authors have reported a shorter method consisting of two washing steps aimed at facilitating an esterification process between the hydroxyl groups of cellulose and the carboxyl groups from the citric acid solution [71]. This chemical modification enhances both the adsorption efficiency and the structural stability of the material. The procedure involves the following steps:

- (i)

- Washing with abundant distilled water.

- (ii)

- Washing with 1.0 M NaOH for 1 h at room temperature.

- (iii)

- Treatment with citric acid at a concentration of 20% w/w, using Na2HPO4 as a catalyst, and employing 2.5 g of SCOBY per 100 mL of the aforementioned solution.

- (iv)

- Incubation of the treated material at 60 °C for 2 h.

- (v)

- Final washing with abundant distilled water, followed by drying at 50 °C.

Another method evaluated for bacterial cellulose purification involves the use of surfactants, proposing the replacement of conventional synthetic agents with biodegradable alternatives derived from natural sources (e.g., vegetable oils, amino acids) with low toxicity. In the study, sodium cocoyl isethionate (derived from coconut oil), decyl glucoside (derived from glucose and fatty alcohol), and cocamidopropyl betaine (obtained from coconut oil and betaine) were assessed. The evaluation method consisted of immersing the prewashed films in a 2% surfactant solution, incubating them at 60 °C for 3 h, followed by rinsing with distilled water for approximately 90 min. The samples were then frozen at −80 °C and lyophilized. This process facilitates protein solubilization. The approach aims to minimize environmental impact while achieving efficacy comparable to that of synthetic products [70].

5.5. Determination of the Molecular Weight and Rheological Properties of Bacterial Cellulose

Bacterial cellulose has been extensively discussed as a potential alternative among polysaccharides due to its unique properties. Research has provided a more in-depth assessment of the intrinsic and dynamic viscosity of bacterial cellulose solutions using a BS/U tube viscometer, where the data obtained indicate flow times and dynamic viscosity values (i.e., tBC =1.3809 Mw1.3062 and i.e., ηBC = 0.0183 Mw1.3069, respectively), which remain constant when applying the Mark–Houwink–Sakurada equation. These parameters are essential for determining the molecular weight of bacterial cellulose.

Similarly, in determining the molecular weight of bacterial cellulose, studies have employed a purification and transformation process (cellulose acetate), enabling its analysis with a Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) system. Using substitution data, the number of repeating units in each chain was calculated, determining that the molar mass of the anhydroglucose unit is 162 g/mol. Although this is not a direct measurement of bacterial cellulose, it may serve as a starting point for future studies [72].

5.6. SCOBY as an Inoculum Culture

The traditional method used for fermenting “Kombucha,” the original beverage, has solely involved the transfer of the SCOBY. However, models have been documented in which lactic acid bacteria, Zygosaccharomyces, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are used as fermentation process drivers in the medium, resulting in a Kombucha beverage with high antioxidant activity. This suggests that by using these common microorganisms in SCOBY, they produced Kombucha with favorable characteristics [33].

6. Factors Influencing the Multiplication and Production of Polysaccharides

The conditions in the fermentation process directly affect the final product, as well as the attributes or compounds of the active substrate [3].

6.1. Carbon Source

The type and quantity of sugar used in fermentation vary in each region, with reported levels ranging from 1.0 to 100 g/L [3]. Sucrose provides glucose and fructose that will be utilized by the microbiota, with other sources recommending a percentage of 5% in the weight/volume ratio [48]. The same author mentions the use of different carbon sources such as molasses and coconut palm sugar, resulting in higher production of lactic acid and increased cellulose production. The use of glucose, lactose, or fructose as feasible substitutes in fermentation has also been reported [21]. The type of carbon source used will directly impact cellulose formation, with sucrose being one of the most commonly used sources so far [44].

6.2. Temperature

This factor is considered the most important in fermentation, followed by pH, because it can either increase or decrease cellulose production [44]. The temperature can vary depending on the climate of the region being reported, but a temperature close to 25 °C up to a maximum of 30 °C is recommended [3]. A temperature of 30 °C yields greater microbial diversity [48], and it has been noted that at 30 °C, there is increased production of glucuronic acid [21]. This factor has a direct impact on the polyphenol content, as very high temperatures can degrade these compounds, as well as the antioxidants.

The flavor of the product can change with variations in this factor, as reported in beverages with nettle as substrate, fermented at 43 °C, which had high sensory acceptability. However, higher temperatures may cause instability in the microorganisms within the SCOBY, such as Komagataeibacter bacteria [68]. Fermentations performed at temperatures below 30 °C exhibit higher cellulose production due to the comfort of the bacteria Komagataeibacter xylinus [21]. An increase in temperature can proliferate the growth of bacteria such as Streptococcus sp. or Acinetobacter sp. [11].

6.3. pH

One of the most important factors in the action of SCOBY is pH. In the production of both kombucha and other derivatives, there is a clear decrease in pH, which depends on the factors comprising the medium [27]. It is important to mention that adding a percentage of the original SCOBY medium is necessary to ensure a pH lower than 4.6, which will ensure the proper growth of the microbiota [21]. Ensuring a pH between 2.5 and 4.2 will inhibit the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria, and an acidity of 4.5 g/L is considered optimal in terms of flavor [41]. Factors such as pH have been studied, where the use of polynomial models is recommended to evaluate the production of the polysaccharide. The generally recommended optimal pH is 2.5–3.5, which ensures a safe product for consumption, prevents contamination by certain pathogenic bacteria, and provides a desirable flavor [73].

6.4. Fermentation Time

The ideal reported time for successful fermentation is 7–14 days [3]. Fermentations of up to 60 days have been reported, but this leads to a decrease in the antioxidant activity of the beverage at around 53 days [74]. Fermentation should not exceed 56 days because nutrients begin to become scarce, and the accumulation of carbon dioxide between the medium and the SCOBY starts to affect the microbiota of the medium [44].

The fermentation days with the SCOBY can affect its microbial content. It is mentioned that after 14 days of fermentation, there are more bacteria and yeast present in both the SCOBY and the medium. However, after this period, a decrease in the SCOBY and a higher number of viable cells in the liquid are observed [4]. Acetic acid bacteria are found in greater quantities on the film because they can take advantage of and obtain greater amounts of oxygen.

Regarding flavor, time is crucial because longer fermentation produces different notes, such as a vinegary taste if fermented for more than 60 days, which is not recommended [37]. Some authors mention a slight apple cider-like taste after a few days of fermentation. However, the flavor of each medium will depend on the matrix used, which can vary between grains, spices, fruits, vegetables, or tea leaves [21].

Reports indicate that an increase in compounds such as acetic acid or isovalerate is not only responsible for an acidic taste but also for a cheese-like flavor, an undesirable characteristic in a beverage [75]. Time is known to be an important factor; a fermentation period of 6–7 days yields an acceptable flavor, although under certain conditions, some beverages may develop a sour, vinegar-like taste. Likewise, each ingredient used in fermentation can influence the sensory outcome, such as substituting sucrose with less common sweeteners like molasses [48].

6.5. Oxygen

The process of certain aerobic bacteria requires the presence of oxygen. Some mention the use of medium agitation to provide proper aeration [76]. Incorrect oxygenation will hinder the growth and activity of various microorganisms [21]. Better acetic acid production has been demonstrated in agitated fermentations compared to fermentations without movement [34].

6.6. Other

SCOBY production can be affected in its thickness and integrity depending on its handling. For better results, meticulous manipulation is recommended because disturbing the SCOBY can affect its thickness, preventing the layers produced from joining together [22]. The shape and size of the container should also be considered for better multiplication [3]. The use of food-grade materials is recommended to avoid the transfer of any unwanted substances. The use of metallic containers can affect the content of the beverage, resulting in residues within the product, thus obtaining a certain degree of toxicity [33].

7. Alternative Uses

7.1. Medicine

In ancient times, a doctor named Kombucha used the SCOBY fungus to treat the digestive problems of the emperor in 414 A.D. [10]. There are reports indicating the use of SCOBY cellulose as an alternative in the treatment of skin lesions or even burns [74]. Due to its purity and biocompatibility, cellulose has recently been proposed for use in wound dressings and bandages, functioning as a tissue-like material. Its previously mentioned porosity and fluid retention capacity have also led to its consideration as a drug delivery system, although this application has thus far been discussed only as a potential use based on these properties [77]. Cellulose has additionally been associated with tissue engineering, particularly for regenerative purposes, and its structure suggests potential use as a scaffold for artificial skin and soft tissues, including blood vessels [78]. In this context, it is regarded as a low-cost, easily produced, biodegradable, and sustainable material with superior texture compared to commercially available synthetic models. These attributes support the expansion of its applications, including its potential in 3D printing [79]. The feasibility of using SCOBY as a biomaterial is increasingly supported by recent research, which positions this material as a promising solution for addressing health-related challenges, including the treatment of diseases and injuries [80].

7.2. Antimicrobial

Antimicrobial activity has been reported from various sources and is primarily attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds and organic acids, which lower the pH of the medium, thereby preventing the proliferation of certain pathogens. The intracellular acidification of bacterial cells can inhibit glycolysis and block the active transport of nutrients, ultimately arresting microbial growth [49].

In fermentations mediated by the SCOBY, this antimicrobial activity is ascribed to the metabolic products synthesized by its microbial consortium. Among these, volatile organic compounds—particularly those produced during fermentations using fruits or herbs as substrates—can induce cellular damage and inhibit the growth of various microorganisms [25,73]. Additionally, proteins, enzymes, and bacteriocins have also been implicated in some cases [81]. In this regard, in vitro studies have demonstrated the inhibition of growth of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, including enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Bacillus subtilis, Aspergillus niger, and Klebsiella pneumoniae [3], as well as Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Candida albicans (Onsun et al., 2025) [6], Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Proteus mirabilis ATCC 35659, and Erwinia carotovora NCPPB 595 [73].

The antimicrobial activity observed across these studies is contingent upon the concentration of bioactive compounds produced or released. Given the variability in substrates employed, the effectiveness of the final product largely depends on the extent and efficiency of the fermentation process.

7.3. Others

There is a record of supplements in tea fermentations, such as cereals, herbs, mushrooms, and algae [81]. The production of cellulose from SCOBY has started to be utilized in recent years because it is more cost-effective and accessible [28]. The cellulose obtained through this method is used to produce bio-leather or to substitute vegetable cellulose [4], such as the production of carboxymethyl cellulose, which has a high commercial demand and represents an alternative production method. Its use as bacterial cellulose has resulted in the development of an independent, malleable, and environmentally friendly supercapacitor [57,82]. One of the drawbacks of working with this cellulose is its characteristic brown color, a product of the Maillard reaction. Therefore, NaOH is used, an alkaline method that helps clarify the SCOBY and removes the vinegar-like odor it has, or a mixture of polyethylene oxide with NaOH. It is worth mentioning that depending on the pretreatment given to the cellulose, it will acquire different characteristics [60].

Its potential use has been mentioned in technological applications such as bioplastics, bioenergy, food enrichment, and packaging [4,37,63]. Due to the versatility of SCOBY, it has also emerged as a candidate for applications in the field of architecture, serving as an alternative in lamp prototypes due to its ability to withstand high temperatures [4]. In addition to its applications in design, due to its characteristics, SCOBY has been developed as a substitute for animal skins in artistic, design, and commercial projects. There are even efforts to enhance its qualities by giving it properties such as glowing in the dark. There is evidence of successful textile use, including its application in jackets [83]. In terms of environmental impact, SCOBY-derived cellulose has been reported to remove dyes such as methylene blue and brilliant green by up to 100%, a percentage that depends on the cellulose’s specific surface area (143.244 m2/g) and the contact time. However, the study lacks critical information, such as adsorption capacity and kinetic analyses, which are essential to substantiate and generalize these findings. Nonetheless, this represents a potentially innovative and impactful application for environmental protection [23].

Over the years, there have been increasing attempts to be more environmentally responsible. Natural polymers resulting from microorganisms, such as the cellulose from SCOBY, can be a potential material for the production of items like packaging, films, membranes, and textiles, which would have a positive impact on reducing petroleum-based waste [28]. The use of SCOBY for the fermentation of algae such as Sargassum sp. and Ulva sp. improves antidiabetic properties, as they demonstrated the ability to inhibit alpha-amylase with an IC50 value, in addition to containing steroids, tannins, triterpenoids, and phenols [84]. This polysaccharide has been used as a textile, but beyond a single garment, it has also been utilized as a medium for use as a sensor with certain adaptations, indicating its high malleability.

8. Future Perspectives

Although these products offer added value and are inexpensive to produce, further studies are needed to demonstrate their beneficial effects on human health, identify specific effects and determine which have the greatest impact. It is crucial to emphasize the need for further studies on SCOBY, including its chemical composition, functions, and interactions with various food matrices. Research on its activity in both in vitro and in vivo models is required for a better approach. Although the practicality and reproducibility of SCOBY fermentation are evident, in vivo studies are required to better understand its impact on human health. However, the detection of these compounds in fermented foods indicates their functionality.

Furthermore, research into the optimization of production processes and the assessment of the environmental impact of the fermentation industry will contribute to the sustainable development of this growing sector. One of the greatest advantages of polysaccharides is their cost-effectiveness and their wide range of applications, such as in textiles, fermentation of different food matrices for the production of compounds of interest. They are considered safe compared to synthetic polysaccharides, which can be toxic. Polymers like SCOBY cellulose can have biological uses.

9. Conclusions

This review highlights the importance of SCOBY-derived polysaccharides due to their immense potential in the food industry. These biopolymers, primarily bacterial cellulose and other exopolysaccharides, play a crucial role in the structural integrity and functional properties of fermented products. Their presence enhances texture, viscosity, and water retention, making them compatible with various food matrices. Additionally, these polysaccharides serve as prebiotics, supporting gut microbiota and promoting health benefits. Alongside other bioactive compounds produced by the microbial consortium—such as polyphenols, antioxidants, and organic acids—SCOBY-derived polysaccharides contribute to the nutritional value and functional properties of fermented foods. In conclusion, SCOBY polysaccharides represent a promising and sustainable alternative for the food industry, facilitating the production of high-value fermented foods that support a balanced and healthy diet.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.F.-G. and M.R.M.; investigation, R.M.S.-S.; supervision, writing—original draft, R.M.S.-S.; writing—review and editing, A.C.F.-G., M.R.M., R.R.-H., P.A.-Z. and J.A.A.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Council of Humanities, Sciences and Technologies (CONAHCYT) of Mexico for the scholarship granted as financial support with the scholarship number 1319549, and the Department of Food Research of the Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yermagambetova, A.; Tazhibayeva, S.; Takhistov, P.; Tyussyupova, B.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A.; Musabekov, K. Microbial Polysaccharides as Functional Components of Packaging and Drug Delivery Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absharina, D.; Padri, M.; Veres, C.; Vágvölgyi, C. Bacterial Cellulose: Biofabrication to Applications in Sustainable Fashion and Vegan Leather. Fermentation 2025, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolak, H.; Piechota, D.; Kucharska, A. Kombucha Tea—A Double Power of Bioactive Compounds from Tea and Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeasts (SCOBY). Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laavanya, D.; Shirkole, S.; Balasubramanian, P. Current challenges, applications and future perspective of SCOBY cellulose of Kombucha fermentation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, E.; Rahi, D. Commercial Utilization of Microbial Polysaccharides: A Brief Global Perspective. Ann. Exp. Mol. Biol. 2024, 6, 000124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsun, B.; Toprak, K.; Sanlier, N. Kombucha Tea: A Functional Beverage and All its Aspects. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira de Miranda, J.; Fernandes Ruiz, L.; Borges Silva, C.; Matsue Uekane, T.; Alencar Silva, K.; Goncalves Martins Gonzalez, A.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Kombucha: A review of substrates, regulations, composition, and biological properties. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, Y.A.G.; El-Naggar, M.E.; Abdel-Megeed, A.; El-Newehy, M.H. Recent advancements in microbial polysaccharides: Synthesis and applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, T.R.; Nascimento, A.D.F.; Valencia, G.A. Kombucha Bacterial Cellulose: A Promising Biopolymer for Advanced Food and Nonfood Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufresne, C.; Farnworth, E. Tea, Kombucha, and health: A review. Food Res. Int. 2000, 33, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.G.; de Lima, M.; Schmidt, V.C. Technological aspects of kombucha, its applications and the symbiotic culture (SCOBY), and extraction of compounds of interest: A literature review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwetcharoen, H.; Phung, L.T.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, S.; Tippayawat, P.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Kombucha Healthy Drink—Recent Advances in Production, Chemical Composition and Health Benefits. Fermentation 2023, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, S.; Safari, M.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Golmakani, M.T. Development of fermented date syrup using Kombucha starter culture. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczyk, A.M.; Silarski, M.; Kaczmarek, M.; Harasymczuk, M.; Dziedzic-Kocurek, K.; Uhl, T. Shielding properties of the kombucha—Derived bacterial cellulose. Cellulose 2025, 32, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Singh, M.K.; Singh, A. Bacterial cellulose: A smart biomaterial for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 39, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Cleveland, D.; Tran, G.; Joseph, F. Potential of bacterial cellulose for sustainable fashion and textile applications: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 6685–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Cubas, A.L.; Provin, A.P.; Aguilar Dutra, A.R.; Mouro, C.; Gouveia, I.C. Advances in the Production of Biomaterials through Kombucha Using Food Waste: Concepts, Challenges, and Potential. Polymers 2023, 15, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D.; Gutiérrez-Pensado, R.; Isabel Bravo, F.; Muguerza, B. Novel kombucha beverages with antioxidant activity based on fruits as alternative substrates. LWT 2023, 189, 115482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.; Curtin, C. Microbial Composition of SCOBY Starter Cultures Used by Commercial Kombucha Brewers in North America. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.; Trzaskowska, M.; Scibisz, I.; Pokorski, P. Application of the “SCOBY” and Kombucha Tea for the Production of Fermented Milk Drinks. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, A.; Sousa, P.; Wurlitzer, N. Alternative raw materials in kombucha production. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofer, N.; Alistar, M. Felt Experiences with Kombucha SCOBY: Exploring First-person Perspective with Living Matter. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’23), Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigiro, L.M.; Maksum, A.; Donanta, D. Utilization of Cellulose Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast (SCOBY) with Sweet Tea Media as Methylene Blue and Brilliant Green Biosorbent Material. J. Mater. Explor. Find. 2023, 2, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenrak, S.; Charumanee, S.; Sirisa-Ard, P.; Bovonsombut, S.; Kumdhitiahutsawakul, L.; Kiatkarun, S.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Chitov, T.; Bovonsombut, S. Nanobacterial Cellulose from Kombucha Fermentation as a Potential Protective Carrier of Lactobacillus plantarum under Simulated Gastrointestinal Tract Conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digel, I.; Akimbekov, N.; Rogachev, E.; Pogorelova, N. Bacterial cellulose produced by Medusomyces gisevii on glucose and sucrose: Biosynthesis and structural properties. Cellulose 2023, 30, 11439–11453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, D. Biological activities of kombucha beverages: The need of clinical evidence. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluz, M.I.; Pietrzyk, K.; Pastuszczak, M.; Kacaniova, M.; Kita, A.; Kapusta, I.; Zagula, G.; Zagrobelna, E.; Strús, K.; Marciniak-Lukasiak, K.; et al. Microbiological and Physicochemical Composition of Various Types of Homemade Kombucha Beverages Using Alternative Kinds of Sugars. Foods 2022, 11, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryszewska, M.A.; Tabandeh, E.; Jędrasik, J.; Czarnecka, M.; Dzierżanowska, J.; Ludwicka, K. SCOBY Cellulose Modified with Apple Powder—Biomaterial with Functional Characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Wang, X.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Yi, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Characterization of SCOBY-fermented kombucha from different regions and its effect on improving blood glucose. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Bouajila, J.; Pace, M.; Leech, J.; Cotter, P.D.; Souchard, J.; Taillandier, P.; Beaufort, S. Metabolome-microbiome signatures in the fermented beverage, Kombucha. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 333, 108778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor-Calvo, E.; Morales, D. Chemical and Aromatic Changes during Fermentation of Kombucha Beverages Produced Using Strawberry Tree (Arbutus unedo) Fruits. Fermentation 2023, 9, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.M.; Suárez, L.V.; Jayabalan, R.; Oros, H.; Escalante-Aburto, A. A review on health benefits of kombucha nutritional compounds and metabolites. J. Food 2017, 16, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, M.; Mitchell, A.L.; Finn, R.D.; Gürel, F. Microbial composition of Kombucha determined using amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzni Sharifudin, S.; Yong Ho, W.; Keong Yeap, S.; Abdullah, R.; Peng Koh, S. Fermentation and characterisation of potential kombucha cultures on papaya-based substrates. LWT 2021, 151, 112060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Tan, Q.; Tang, Q.; Tong, Z.; Yang, M. Research progress on alternative kombucha substrate transformation and the resulting active components. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1254014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, D.A.; Maghrawy, H.H.; Abdel, H. Biosynthesis of bacterial cellulose nanofibrils in black tea media by a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast isolated from commercial kombucha beverage. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zailani, N.S.; Adnan, A. Subtrates and metabolic pathways in symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) fermentation: A mini review. J. Teknol. 2022, 84, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánovas, B.M.; Viguera, C.G.; Medina, S.; Perles, R.D. ‘Kombucha’-like Beverage of Broccoli By-Products: A New Dietary Source of Bioactive Sulforaphane. Beverages 2023, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Pu, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Recent progress in the study of taste characteristics and the nutrition and health properties of organic acids in foods. Foods 2022, 11, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esatbeyoglu, T.; Sarikaya Aydin, S.; Gültekin Subasi, B.; Erskine, E.; Gök, R.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Yilmaz, B.; Özogul, F.; Capanoglu, E. Additional advances related to the health benefits associated with kombucha consumption. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 6102–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende Cardoso, R.; Oliveira Neto, R.; Thomaz dos Santos D’Almeida, C.; Pimenta Do Nascimento, T.; Girotto Pressete, C.; Azevedo, L.; Duarte Martino, S.H.; Claudio Cameron, L.; Ferreira Larraz, M.S.; Ribeiro de Barros, F.A. Kombuchas from green and black teas have different phenolic profile, which impacts their antioxidant capacities, antibacterial and antiproliferative activities. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, R.; Sadat Naghavi, N.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Doudi, M.; Shahanipour, K. Kombucha microbial starter with enhanced production of antioxidant compounds and invertase. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Kałdunska, J.; Kochman, J.; Janda, K. Chemical Profile and Antioxidant Activity of the Kombucha Beverage Derived from White, Green, Black and Red Tea. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini, T.; Nageshwari, K.; Vimaladhasan, S.; Parag Prakash, S.; Balasubramanian, P. Machine learning prediction of SCOBY cellulose yield from Kombucha tea fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 18, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMR Expert Market Research. Perspectivas del Mercado Mundial del té de Kombucha. 2023. Available online: https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/reports/kombucha-tea-market (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Anantachoke, N.; Duangrat, R.; Sutthiphatkul, T.; Ochaikul, D.; Mangmool, S. Kombucha Beverages Produced from Fruits, Vegetables, and Plants: A Review on Their Pharmacological Activities and Health Benefits. Foods 2023, 12, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Rutherfurd-markwick, K.; Zhang, X.; Mutukumira, A.N. Kombucha: Production and Microbiological Research†. Foods 2025, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, L.M.; Lynch, K.M.; Sahin, A.W. Advances in Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 2, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed, L.; Sana, M.; Hamdi, M. Microbiological, Biochemical, and Functional Aspects of Fermented Vegetable and Fruit Beverages. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 5790432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.P.; Sew, Y.S.; Sabidi, S.; Maaraf, S.; Sharifudin, S.A.; Abdullah, R. SCOBY papaya beverages induce gut microbiome interaction as potential antiobesity in weight management control supplement. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 6, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luvison, A.; Zago Dangui, A.; Priscila De Lima, K. Desenvolvimento de kombucha de alecrim (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) saborizado com manga (Mangifera indica L.). Rev. Bras. Tecnol. Agroindustrial 2023, 17, 4057–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Ron, F.; de la Rosa, M.J.; Hernández, I. Development of a no added sugar kombucha beverage based on germinated corn. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz da Silva, M.; Cristina de Souza, A.; Roberto Faria, E.; Molina, G.; de Andrade Neves, N.; Aley Morais, H.; Ribeiro Dias, D.; Freitas Schwan, R.; Lacerda Ramos, C. Use of Kombucha SCOBY and Commercial Yeast as Inoculum for the Elaboration of Novel Beer. Fermentation 2022, 8, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iličić, M.; Milanović, S.; Kanurić, K.; Vukić, V.; Vukić, D.; Stojanović, B. Improving the texture and rheology of set and stirred kombucha fermented milk beverages by addition of transglutaminase. Mljekarstvo 2021, 71, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Van Mullem, J.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. The chemistry and sensory characteristics of new herbal tea-based kombuchas. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sknepnek, A.; Tomić, S.; Miletić, D.; Lević, S.; Čolić, M.; Nedović, V.; Nikšić, M. Fermentation characteristics of novel Coriolus versicolor and Lentinus edodes kombucha beverages and immunomodulatory potential of their polysaccharide extracts. Food Chem. 2020, 342, 128344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukié, D.; Pavlié, B.; Vukií, V.; Ilieié, M.; Kanurié, K.; Bjekié, M.; Zekovié, Z. Antioxidative capacity of fresh kombucha cheese fortified with sage herbal dust and its preparations. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartora, B.; Sant’Anna, V.; Hickert, L.R.; Fensterseifer, M.; Ayub Zachia, A.M.; Flôres, S.H.; Perez, K.J. Factors influencing kombucha production: Effects of tea composition, sugar, and SCOBY. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.; Zarei, M.; Gholami, A.; Lai, C.W.; Chiang, W.H.; Omidifar, N.; Bahrani, S.; Mazraedoost, S. Recent Progress in Chemical Composition, Production, and Pharmaceutical Effects of Kombucha Beverage: A Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 4397543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiński, K.; Jarosz, M.; Grudzień, J.; Pawlik, J.; Zastawnik, F.; Pandyra, P.; Kołodziejczyk, A.M. Hydrogel bacterial cellulose: A path to improved materials for new eco-friendly textiles. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5353–5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.O.; Smidt Ode, S. Microbial Composition, Bioactive Compounds, Potential Benefits and Risks Associated with Kombucha: A Concise Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, P.; Pitts, E.R.; Budner, D.; Thompson-witrick, K.A. Kombucha: Biochemical and microbiological impacts on the chemical and flavor profile. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cheng, M.; Li, Z.; Guan, S.; Cai, B.; Li, Q.; Rong, S. Composition and biological activity of rose and jujube kernel after fermentation with kombucha SCOBY. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanderley, B.R.; Lima, M.E.; Oliveira, A.K.; Sartori, G.V.; Stroschein, M.R.; Amboni, R.D.; Fritzen-Freire, C.B.; Aquino, A.C. Influence of the addition of strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum) pulp on the content of bioactive compounds in kombuchas with yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis). Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, e00063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroli, C.; Sordini, B.; Daidone, L.; Veneziani, G.; Esposto, S.; Urbani, S.; Selvaggini, R.; Servili, M.; Taticchi, A. Recovery and valorization of food industry by-products through the application of Olea europaea L. leaves in kombucha tea manufacturing. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wyk, N.; Binder, J.; Ludszuweit, M.; Köhler, S.; Brezina, S.; Semmler, H.; Pretorius, I.S.; Rauhut, D.; Senz, M.; von Wallbrunn, C. The Influence of Pichia kluyveri Addition on the Aroma Profile of a Kombucha Tea Fermentation. Foods 2023, 12, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıkmış, S.; Tuğgüm, S. Evaluation of Microbiological, Physicochemical and Sensorial Properties of Purple Basil Kombucha Beverage. Turk. J. Agric.—Food Sci. Technol. Ava 2019, 7, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.; Tang, S.; Azi, F.; Hu, W.; Dong, M. Use of kombucha consortium to transform soy whey into a novel functional beverage. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 52, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watawana, M.I.; Jayawardena, N.; Gunawardhana, C.B.; Waisundara, V.Y. Original article Enhancement of the antioxidant and starch hydrolase inhibitory activities of king coconut water (Cocos nucifera var. aurantiaca) by fermentation with kombucha ‘tea fungus’. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakht, A.; van Zyl, E.M.; Larson, S.; Fenlon, S.; Coburn, J.M. Bacterial Cellulose Purification with Non-Conventional, Biodegradable Surfactants. Polysaccharides 2024, 5, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Q.; Chin, N.L.; Talib, R.A.; Basha, R.K. Modelling pH Dynamics, SCOBY Biomass Formation, and Acetic Acid Production of Kombucha Fermentation Using Black, Green, and Oolong Teas. Processes 2024, 12, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lanot, A.; Mao, N. The relationship between molecular weight of bacterial cellulose and the viscosity of its copper (II) ethylenediamine solutions. Cellulose 2024, 31, 7973–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]