Assessment of Agroecological Factors Shaping the Population Dynamics of Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Puton) in Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Locations

2.2. Plant Material

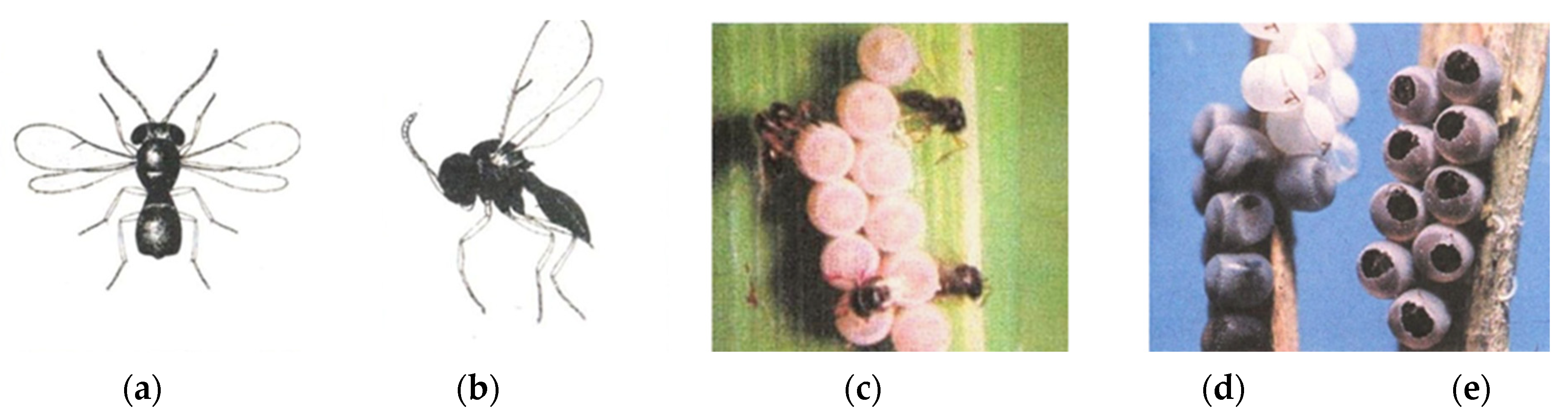

2.3. Pest Research Methods

2.4. Methods for Calculating the Main Indicators

- Tave—average daily temperature;

- Tthreshold—developmental threshold temperature;

- N—number of days with a temperature exceeding the threshold.

- R—total precipitation (mm) for the period with temperatures above +10 °C;

- ∑—sum of temperatures (°C) for the same period.

3. Results

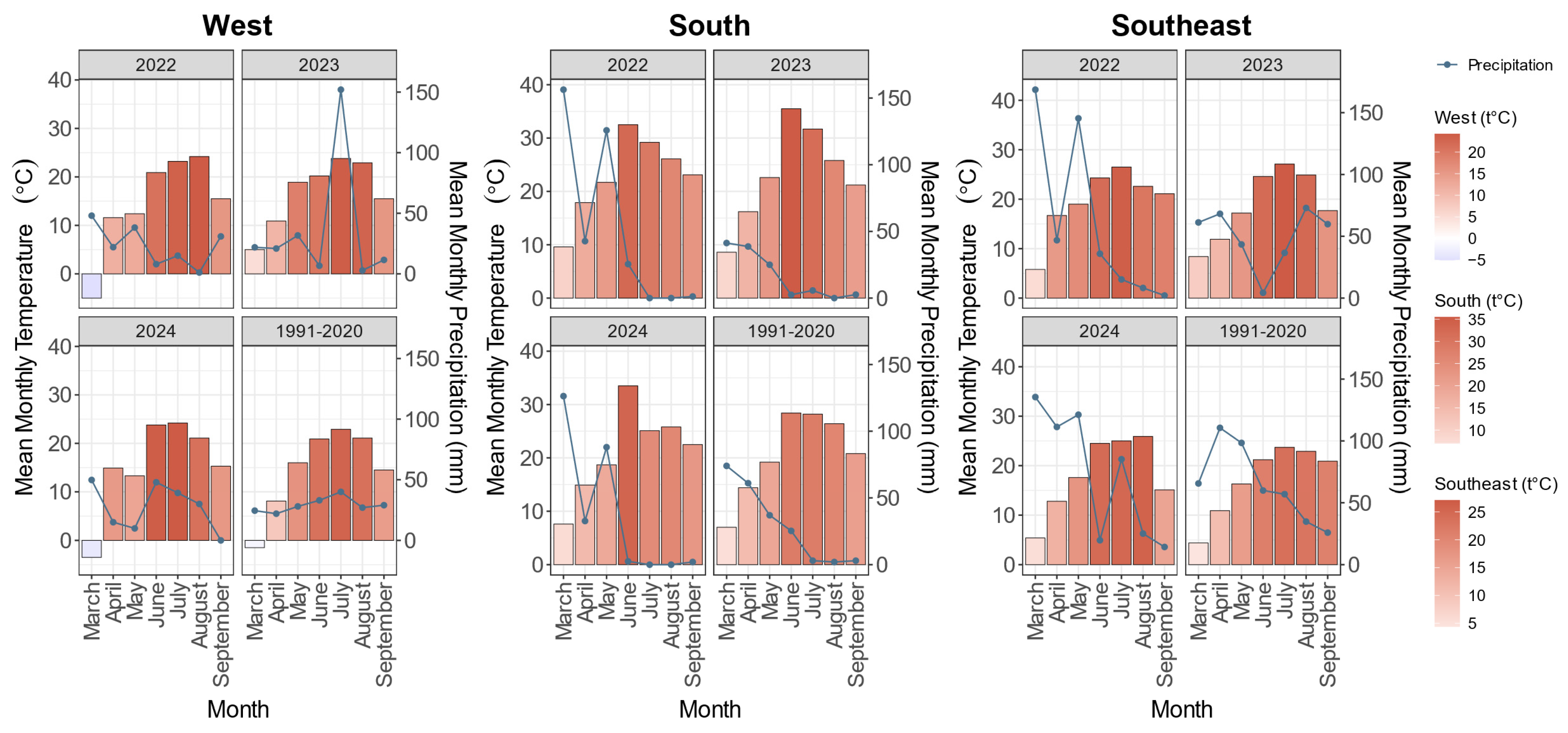

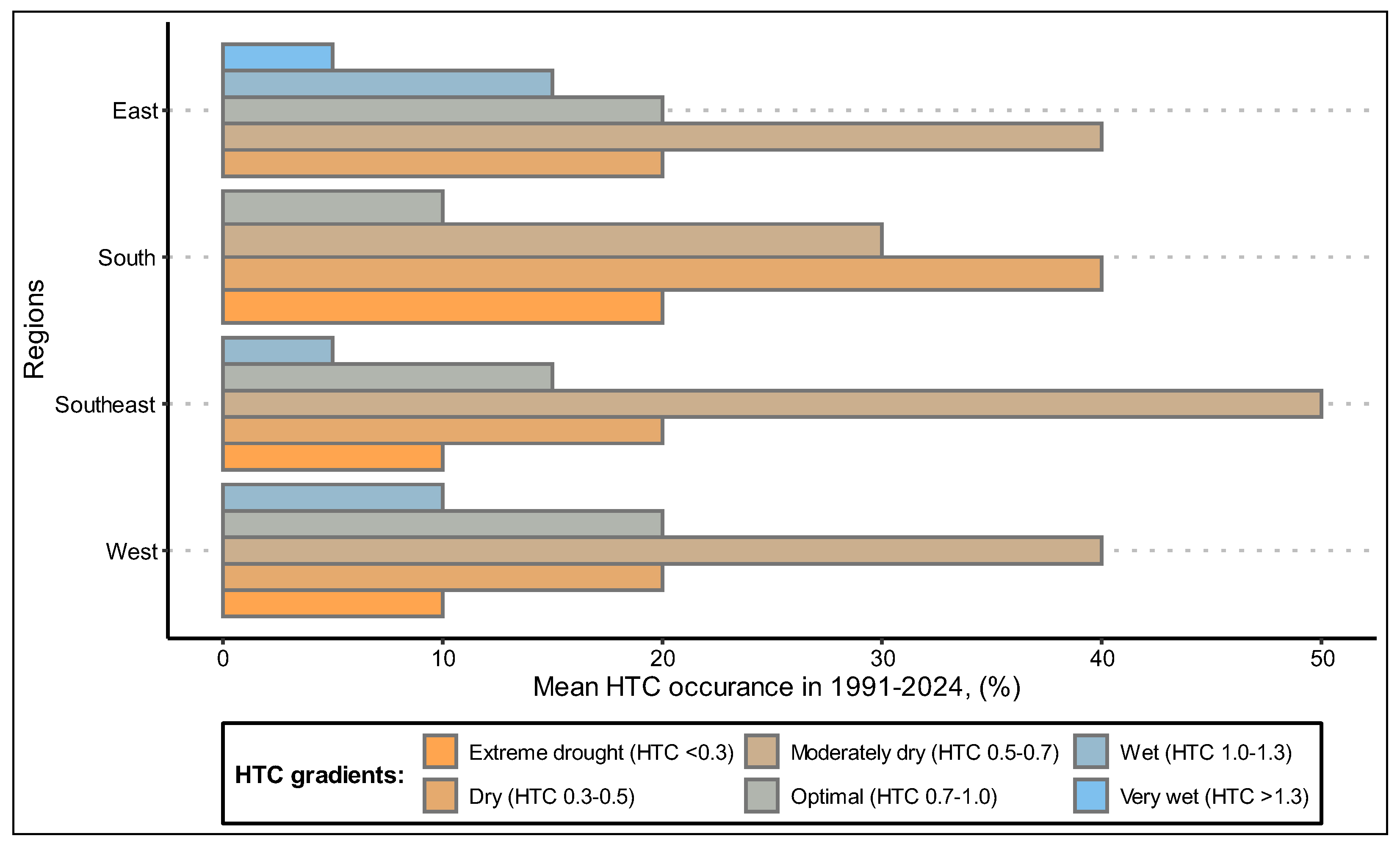

3.1. Study of Weather and Climatic Factors

3.2. Study of Biotic Factors

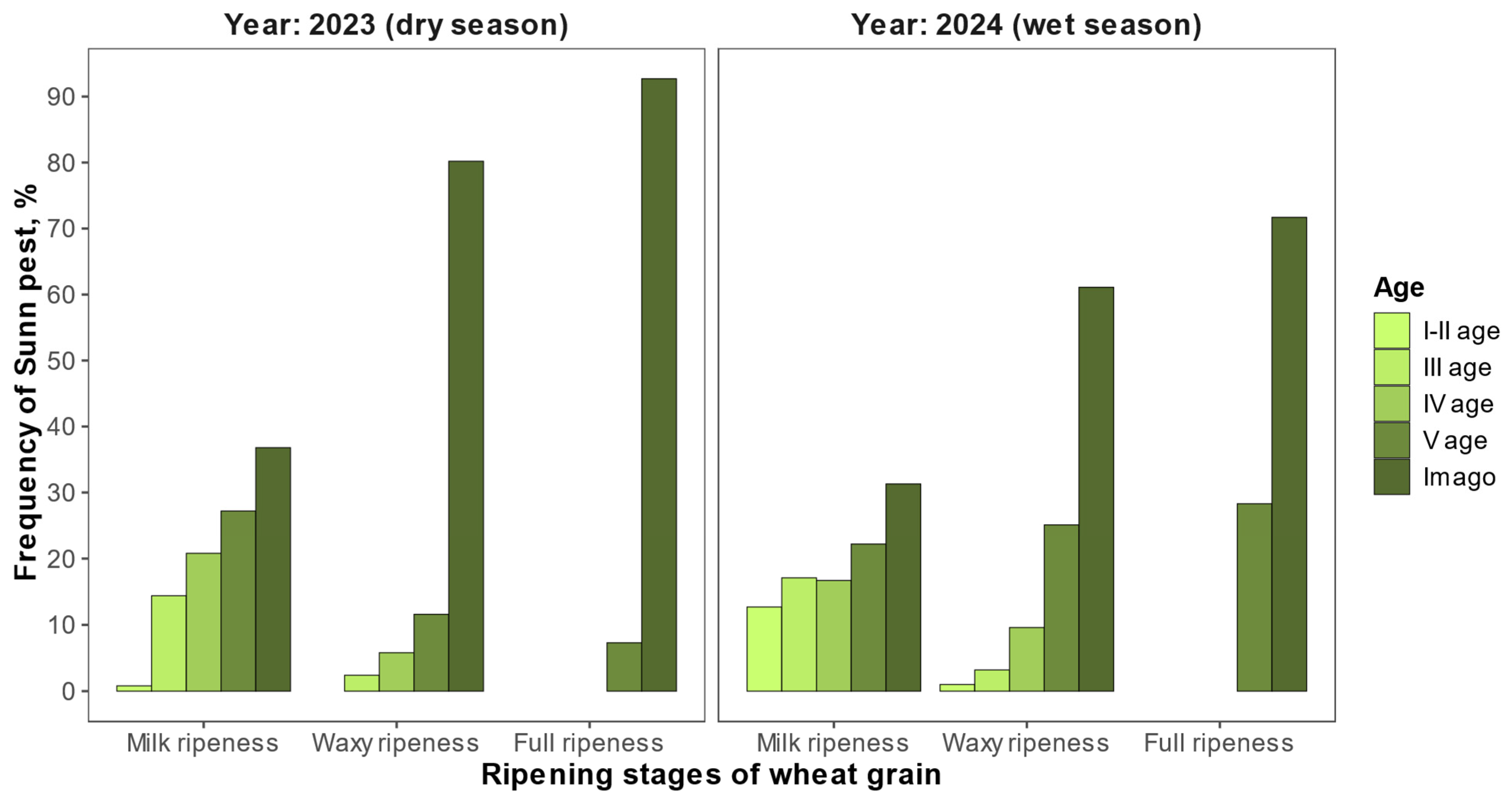

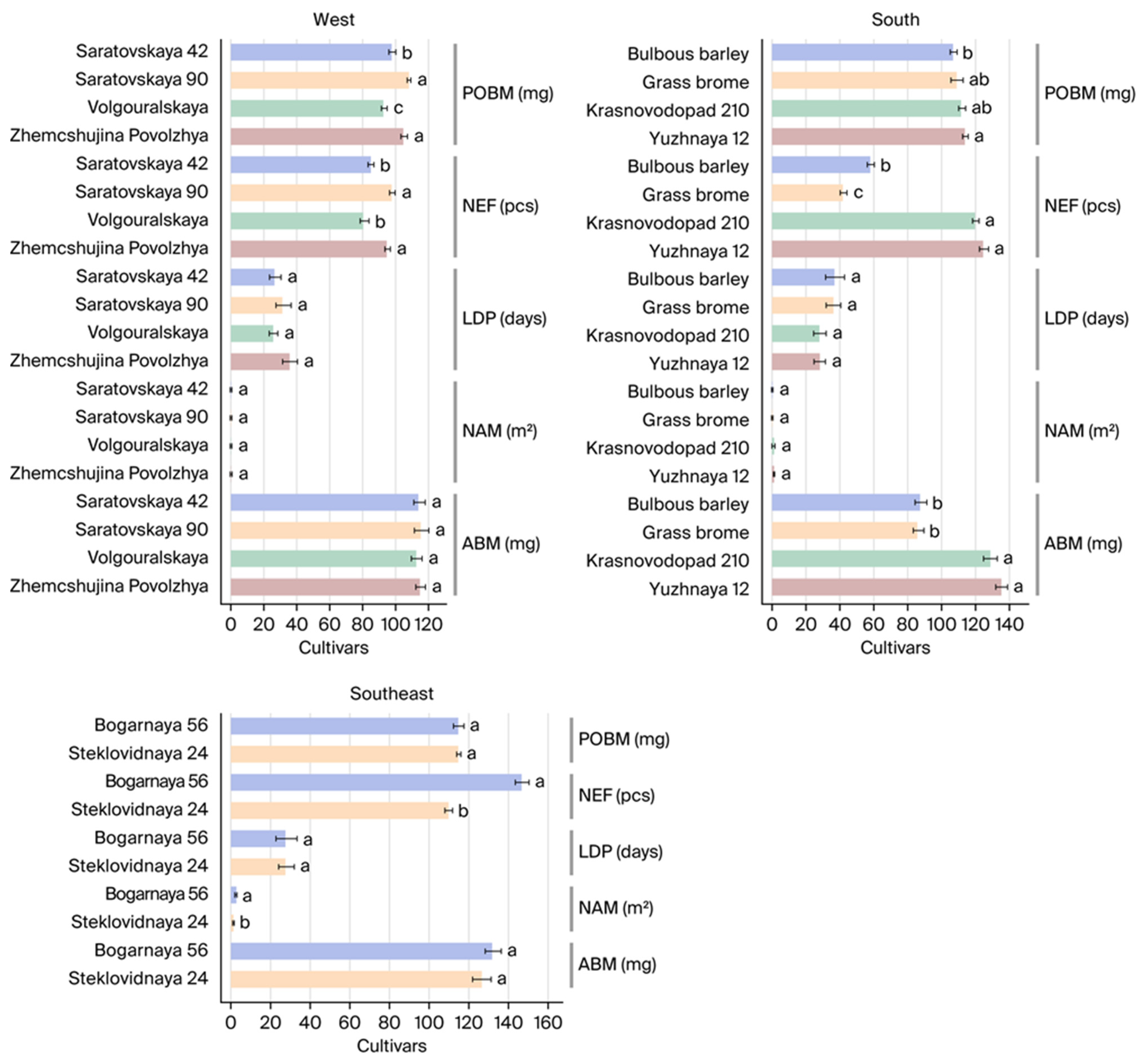

3.3. Study of Feeding Factors

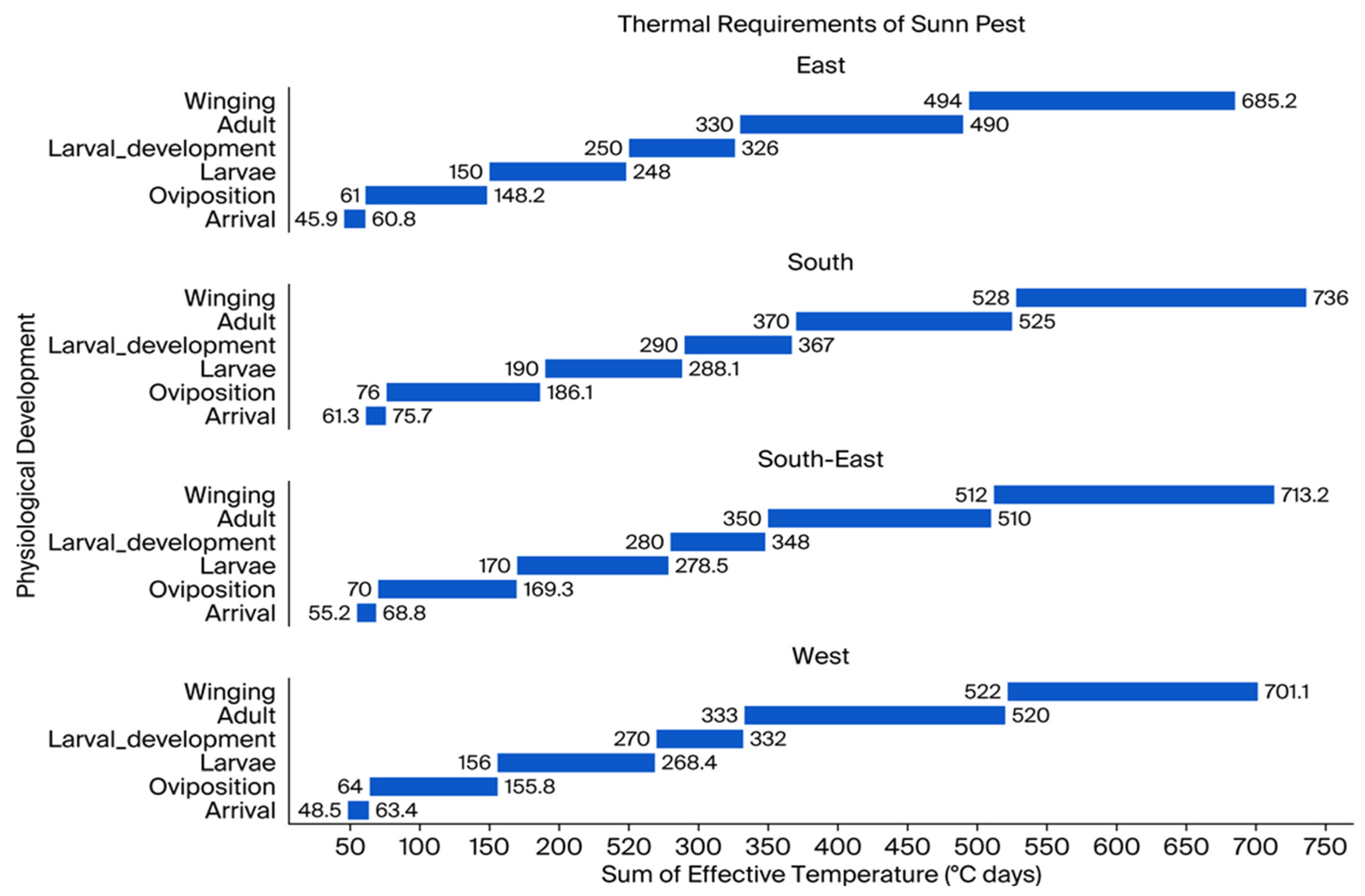

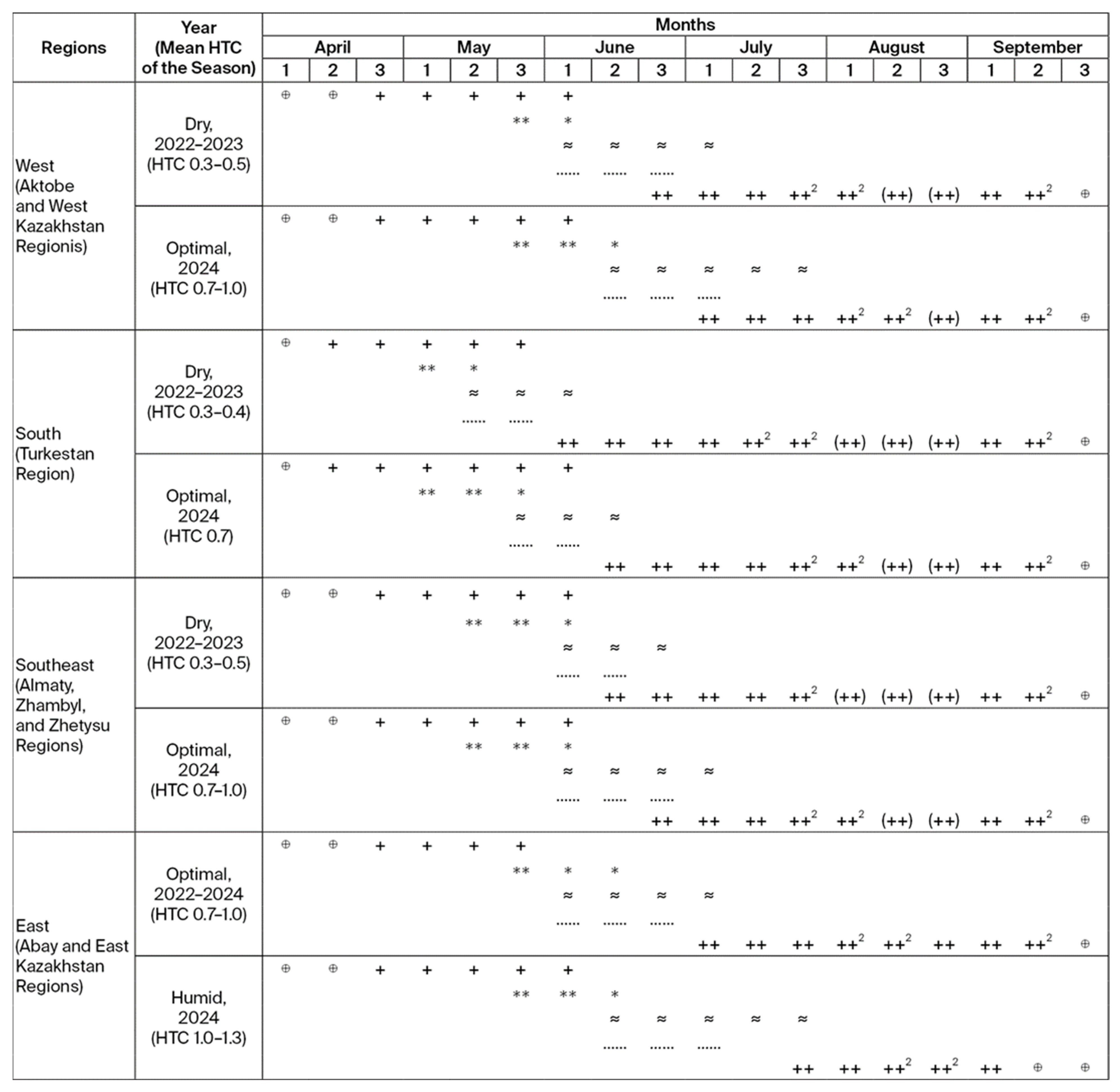

3.4. Phenological Study of Sunn Pest Development Across the Regions of Kazakhstan, 2022–2024

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pavlushin, V.A.; Vilkova, N.A.; Sukhoruchenko, G.I.; Nefedova, L.I.; Kapustkina, A.V. Sunn Pest and Other Cereal Bugs; St. Petersburg, Russia, 2015; 280p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Emebiri, L.; El Bousshini, M.; Tan, M.-K.; Ogbonnaya, F.C. Field-based screening identifies resistance to Sunn pest (Eurygaster integriceps) feeding at vegetative stage in elite wheat genotypes. Crop Past. Sci. 2017, 68, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, A.; Parker, B.L. A review of research on Sunn Pest {Eurygaster integriceps Puton (Hemiptera: Scutelleridae)} management published 2004–2016. J. Asia-Pacific Ent. 2018, 21, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rsaliyev, S.S.; Sarbaev, A.T.; Eserkenov, A.K. The development of a Sunn Pest on winter wheat in the grain-growing regions of Kazakhstan. Izdenister Natizheler (Res. Results) 2024, 2–1, 359–367. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekhin, V.T. Sunn Pest. Plant Prot. Quar. 2002, 4, 1–32. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tafaghodinia, B.; Majdabadi, M. Temperature based model to forecasting attack time of the Sunn Pest Eurygaster integriceps Put. in wheat fields of Iran. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2005, 1, 395–397. [Google Scholar]

- Dizlek, H.; Özer, M.S. Improvement bread characteristics of high level sunn pest (Eurygaster integriceps) damaged wheat by using transglutaminase and some additives. J. Cer. Sci. 2017, 77, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapustkina, A.V.; Frolov, A.N. Wheat Grain Damage by Eurygaster integriceps Puton (Hemiptera, Scutelleridae): Diagnostics and Detection Methods. Entomol. Rev. 2022, 102, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Order of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan Dated June 10, 2022 No. 188 “On Amending the Order of the Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated March 30, 2015 No. 4-4/282 “On Approval of the List of Quarantine Objects and Alien Species in Relation to Which Plant Quarantine Measures Are Established and Implemented, and the List of Particularly Dangerous Pests”. Available online: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=34809481&show_di=1&pos=33;-57#pos=33;-57 (accessed on 23 November 2025). (In Russian).

- Khalaf, M.Z.; Alrubeai, H.F.; Sultan, A.A.; Abdulkareem, A.M. Evaluating Some Insecticides for Controlling the Sunn Pest Eurygaster spp. Puton (Hemiptera: Scutelleridae) under Field Conditions. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2017, 7, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Markarova, J.R. Effectiveness of insecticides against Sunn pest depending on the term of their application. Int. J. Human. Nat. Sci. 2018, 9, 99–103. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorokhov, M.N.; Dolzhenko, V.I.; Silaev, A.I. Improving the range of chemical protection products for winter wheat from the Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Put.). Agrochemistry 2019, 11, 38–47. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekhin, V.T.; Yu, Y.M. Biological protection of cereals from pests. Prot. Quaran. Plants 1998, 10, 18–20. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sukhoruchenko, G.I. The resistance of harmful organisms to pesticides is a problem of plant protection in the second half of the 20th century in the CIS countries. Bull. Plant Prot. 2001, 1, 18–37. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Asseng, S.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; Rötter, R.P.; Lobell, D.B.; Cammarano, D.; Kimball, B.A.; Ottman, M.J.; Wall, G.W.; White, J.W.; et al. Rising temperatures reduce global wheat production. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, A.A.; Farooq, M.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Nawaz, A.; Jabran, K.; Siddique, K.H.M. Impact of climate change on biology and management of wheat pests. Crop Prot. 2020, 137, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insect pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.; Aleem, K.; Sandhu, K.; Shamoon, F.; Fatima, T.; Ehsan, M.; Shaukat, F. A Mini Review on Insect Pests of Wheat and Their Management Strategies. Int. J. Agric. Biosci. 2023, 12, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Qiu, X.; Kang, M.; Zhang, L.; Lu, W.; Liu, B.; Tang, L.; Xiao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; et al. Evaluating the impacts of climatic factors and global climate change on the yield and resource use efficiency of winter wheat in China. Eur. J. Agric. 2024, 159, 127295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zharmukhamedova, G.; Sarbaev, A. Sunn Pest in Central Asia: An Historical Perspective. In Sunn Pest Management: A Decade of Progress 1994–2004; Arab Society for Plant Protection: Beirut, Lebanon, 2007; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rsaliyev, S.S.; Yeserkenov, A.K. Resistance of winter wheat to damage by Sunn Pest in the south-east of Kazakhstan. Sci. Innov. 2024, 3, 94–99. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilmenbaev, A.T. The Sunn Pest and Control Measures; Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1969; 45p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tilmenbaev, A.T. Some features of the ecology of the Sunn Pest in Southern Kazakhstan. Sci. Works Kazakh Agric. Inst. 1976, 19, 10–19. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sarbaev, A.T. Sunn Pest in the Western Kazakhstan. In Ecology of Plant Diseases and Pests in Kazakhstan and Control Measures; Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1980; pp. 13–18. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tilmenbaev, A.T.; Sarbaev, A.T.; Beksultanov, S.Z. The main environmental factors regulating the number of Sunn Pest in Kazakhstan. In Ecology of Plant Diseases and Pests in Kazakhstan and Control Measures; Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, 1980; pp. 3–13. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tilmenbaev, A.T.; Beksultanov, S.Z.; Sarbaev, A.T. The main elements of integrated control of the sunn pest in Kazakhstan. In Noveishie Dostizheniya Sel’skokhozyaistvennoi Entomologii, Vil’nyus; 1981; pp. 184–186. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- The State Register of breeding achievements recommended for use in the Republic of Kazakhstan; Astana, Kazakhstan, 2021; 125p. (In Russian)

- Fedin, M.A. Methodology of state variety testing of agricultural crops. Mosc. USSR Minist. Agric. 1989, 2, 250p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Dospekhov, B.A. The Methodology of Field Experience; Agropromizdat: Moscow, USSR, 1985; 351p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Artokhin, K.S. Pests of Agricultural Crops. Volume 1: Pests of Grain Crops; Pechatny Gorod: Moscow, Russia, 2013; pp. 185–204. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Afonin, A.N.; Milyutina, E.A.; Musolin, D.L. Methods for calculating sums of effective temperatures from monthly average temperature data and producing of global maps for ecological and geographical modelling. Meteorol. i Gidrolog. 2024, 3, 78–86. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobojonova, I.; Aw-Hassan, A. Impacts of climate change on farm income security in Central Asia: An integrated modeling approach. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 188, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, B.; Poudel, A.; Aryal, S. The impact of climate change on insect pest biology and ecology: Implications for pest management strategies, crop production, and food security. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannig, B.; Pollinger, F.; Gafurov, A.; Vorogushyn, S.; Unger-Shayesteh, K. Impacts of Climate Change in Central Asia. In Encyclopedia of the Anthropocene, (Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences); Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranipour, S.; Pakdel, A.K.; Radjabi, G. Life history parameters of the Sunn pest, Eurygaster integriceps, held at four constant temperatures. J. Insect Sci. 2010, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivantsova, E.A. Bioecology of Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Put.) in the conditions of the Lower Volga region. Bull. Volgograd State Univ. Ser. 11 Nat. Sci. 2013, 2, 45–52. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Schierhorn, F.; Hofmann, M.; Adrian, I.; Bobojonov, I.; Müller, D. Spatially varying impacts of climate change on wheat and barley yields in Kazakhstan. J. Arid. Environ. 2020, 178, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnichuk, F.; Alekseeva, S.; Hordiienko, O.; Nychyporuk, O.; Borysenko, A. Influence of irrigation on the Sunn pest Eurygaster integriceps Put. (Insecta: Heteroptera) in the Central Forest-Steppe of Ukraine. Ecol. Quest. 2023, 34, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-I.; Yu, Y.-Y.; Wen, F.-I.; Liu, P.-T. Status of food security in East and Southeast Asia and challenges of climate change. Climate 2022, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islyami, A.; Aldashev, A.; Thomas, T.S.; Dunston, S. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture in Kazakhstan. Silk Road A J. Eurasian Dev. 2020, 2, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatayev, M.; Clarke, M.; Salnikov, V.; Bekseitova, R.; Nizamova, M. Monitoring climate change, drought conditions and wheat production in Eurasia: The case study of Kazakhstan. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelyanov, N.A.; Kritskaya, E.E.; Eskov, I.D.; Dubrovin, V.V. Population dynamics of the Sunn pest in agroecosystems of the Volga region. Agrar. Nauchnyy Zhurnal 2018, 7, 6–10. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kamenchenko, S.E.; Strizhkov, N.I.; Naumova, T.V. Reproduction features of cereal bugs in agrocenoses of Lower Volga area. Zashchita I Karantin Rasteniy 2013, 7, 41–43. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Trissi, A.N.; El Bouhssini, M.; Ibrahem, J.; Abdulhai, M.; Reid, W. Survey of Egg Parasitoids of Sunn Pest in Northern Syria. In Sunn Pest Management: A Decade of Progress 1994–2004; Arab Society for Plant Protection: Beirut, Lebanon, 2007; pp. 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Neymorovets, V.V. Distribution of species of the genus Eurygaster (Heteroptera: Scutelleridae) in Russia. Bull. Plant Prot. 2019, 4, 36–48. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I.D. Immunity of field crops to insects and mites. In Immunitet Polevykh Kul’tur k Nasekomym i Kleshcham; Zoologicheskiĭ Institut, Akademiya Nauk SSSR: Leningrad, USSR, 1985; 321p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kapustkina, A.V.; Khilevskiy, V.A. Population and harmfulness dynamics of the Sunn Pest Eurygaster integriceps Put. (Heteroptera, Scutelleridae) in wheat crops of the Ciscaucasia steppe zone. Entomol. Rev. 2020, 100, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würschum, T.; Leiser, W.L.; Langer, S.M.; Tucker, M.R.; Miedaner, T. Genetic Architecture of Cereal Leaf Beetle Resistance in Wheat. Plants 2020, 9, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fayyadh, M.J.; Najim, S.A.; Al-Husainawi, K.J. Description of Sunn Pest (Hemiptera: Scutelleridae) and Camponotus spp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), as their predator, from the wheat fields of Thi-Qar province southern Iraq. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1664, 012142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir-Maafi, M. Modeling temperature-dependent development of Trissolcus grandis Thomson (Hymenoptera: Scelionidae). J. Entomol. Soc. Iran 2024, 44, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, A.N. Patterns of pest population dynamics and phytosanitary forecast. Bull. Plant Prot. 2019, 3, 4–33. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirinyan, J.A. Methods of Pesticide-free protection of winter wheat. Plant Prot. Quar. 2015, 2, 9–13. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Morgounov, A.; Tufan, H.A.; Sharma, R.; Akin, B.; Bagci, A.; Braun, H.J.; Kaya, Y.; Keser, M.; Payne, T.S.; Sonder, K.; et al. Global incidence of wheat rusts and powdery mildew during 1969–2010 and durability of resistance of winter wheat variety Bezostaya. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 132, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bouhssini, M.; Nachit, M.; Valkoun, J.; Moussa, M.; Ketata, H.; Abdallah, O.; Abdulhai, M.; Parker, B.L.; Rihawi, F.; Joubi, A.; et al. Evaluation of Wheat and its Wild Relatives for Resistance to Sunn Pest under Artificial Infestation. In Sunn Pest Management: A Decade of Progress 1994–2004; Arab Society for Plant Protection: Beirut, Lebanon, 2007; pp. 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- El Bouhssini, M.; Street, K.; Joubi, A.; Ibrahim, Z.; Rihawi, F. Sources of wheat resistance to Sunn pest, Eurygaster integriceps Puton, in Syria. Genet. Res. Crop Evol. 2009, 56, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauber, M.J.; Tauber, C.A.; Masaki, S. Seasonal Adaptations of Insects; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; 411p, ISBN 0-19-503635-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, D.A.; Denlinger, D.L. Meeting the energetic demands of insect diapause: Nutrient storage and utilization. J. Insect Physiol. 2007, 53, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Bandani, A.R. Comparison of Energy Reserves in Prediapause and Diapausing Adult Sunn Pest, Eurygaster integriceps Puton (Hemiptera: Scutelleridae). J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2013, 15, 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Kooner, R.; Arora, R. Insect pests and crop losses. In Breeding Insect Resistant Crops for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanvand, H.; Izadi, H.; Mohammadzadeh, M. Overwintering Physiology and Cold Tolerance of the Sunn Pest, Eurygaster integriceps, an Emphasis on the Role of Cryoprotectants. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; Dong, Y.; Wang, H.; Du, X. Differentiation of Wheat Diseases and Pests Based on Hyperspectral Imaging Technology with a Few Specific Bands. Phyton—Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 92, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhao, G. Current progress on innovative pest detection techniques for stored cereal grains and thereof powders. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibicsár, S.; Keszthelyi, S. Topographical Based Significance of Sap-Sucking Heteropteran in European Wheat Cultivations: A Systematic Review. Diversity 2023, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motie, J.B.; Saeidirad, M.H.; Jafarian, M. Identification of Sunn-pest affected (Eurygaster Integriceps Put.) wheat plants and their distribution in wheat fields using aerial imaging. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 76, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Munguía, A.; Guerra-Ávila, P.L.; Islas-Ojeda, E.; Flores-Sánchez, J.L.; Vázquez-Martínez, O.; García-Munguía, A.M.; García-Munguía, O. A Review of Drone Technology and Operation Processes in Agricultural Crop Spraying. Drones 2024, 8, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, N.R.; Hill, S.J. Effect of Climate Change on Insect Pest Management. Environ. Pest Manag. 2017, 9, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yuan, Z.; Peng, R.; Leybourne, D.; Xue, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, P. An effective farmer-centred mobile intelligence solution using lightweight deep learning for integrated wheat pest management. J. Industr. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupnov, V.A. Wheat breeding for resistance to the Sunn pest (Eurygaster spp.): Does risk occur? Rus. J. Genet. Appl. Res. 2012, 2, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabolkina, E.N.; Sycheva, O.M.; Syukov, V.V. The use of modified methods for assessing the quality of wheat grains against the background of a bug infestation. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2012, 16, 965–969. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Lin, X.; Wang, D. Uncovering the primary drivers of regional variability in the impact of climate change on wheat yields in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Location | Coordinates | Wheat Cultivars and Forage Grass Species | Surveyed Area, ha/Number of Sunn Pests, pcs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||||

| East | KRIAPG (Branch, Taldykorgan) | N 45°01′42″ E 78°31′50″ | Steklovidnaya 24 | 10/30 | 10/30 | 15/50 |

| Southeast | KRIAPG (Cereal crop nursery, Almalybak) | N 43°23′77″ E 76°69′68″ | Steklovidnaya 24, Bogarnaya 56, Bulbous barley, Grass brome | 28/186 | 34/303 | 49/466 |

| KRIAPG (Rainfed nursery, Karaoy) | N 43°49′49″ E 76°66′21″ | Steklovidnaya 24, Bogarnaya 56, Bulbous barley, Grass brome | 1/29 | 1/53 | 1/120 | |

| LLP “Spatai batyr” | N 42°82′24″ E 73°35′84″ | Steklovidnaya 24 | 10/50 | 10/75 | 10/100 | |

| South | LLP “Krasnovodopad Agricultural Experimental Station” | N 41°46′40″ E 69°43′66″ | Krasnovodopad 210, Yuzhnaya 12, Bulbous barley, Grass brome | 11/55 | 11/43 | 17/107 |

| West | Ural Agricultural Experimental Station | N 51°26′42″ E 51°32′16″ | Saratovskaya 90, Zhemcshujina Povolzhya, Volgouralskaya, Saratovskaya 42 | 5/14 | 5/18 | 5/24 |

| 65 ha/ 364 pcs. | 71 ha/ 522 pcs. | 97 ha/ 867 pcs. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rsaliyev, S.; Sarbaev, A.; Eserkenov, A.; Bastaubayeva, S.; Orazaliev, N.; Baimagambetov, A.; Yermekbayev, K. Assessment of Agroecological Factors Shaping the Population Dynamics of Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Puton) in Kazakhstan. Ecologies 2025, 6, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040081

Rsaliyev S, Sarbaev A, Eserkenov A, Bastaubayeva S, Orazaliev N, Baimagambetov A, Yermekbayev K. Assessment of Agroecological Factors Shaping the Population Dynamics of Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Puton) in Kazakhstan. Ecologies. 2025; 6(4):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040081

Chicago/Turabian StyleRsaliyev, Shynbolat, Amangeldy Sarbaev, Aidarkhan Eserkenov, Sholpan Bastaubayeva, Nurbakyt Orazaliev, Arman Baimagambetov, and Kanat Yermekbayev. 2025. "Assessment of Agroecological Factors Shaping the Population Dynamics of Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Puton) in Kazakhstan" Ecologies 6, no. 4: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040081

APA StyleRsaliyev, S., Sarbaev, A., Eserkenov, A., Bastaubayeva, S., Orazaliev, N., Baimagambetov, A., & Yermekbayev, K. (2025). Assessment of Agroecological Factors Shaping the Population Dynamics of Sunn Pest (Eurygaster integriceps Puton) in Kazakhstan. Ecologies, 6(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecologies6040081