2.1. Geological Background and Data Acquisition

The research area was developed in a typical continental sedimentary basin, where the reservoirs evolved in the process of a complicated geological environment with multiple phases of tectonic movement and structural modification. The dominant sedimentary systems of the delta front-shallow lacustrine type are characterized vertically by frequent sand–mudstone interbedding. The reservoir lithology is compositionally complex: fine sandstone, siltstone, argillaceous siltstone, silty mudstone, mudstone, calcareous sandstone, and coal seams. Influenced by frequent changes in depositional environments and further diagenetic processes, the reservoirs exhibit strong heterogeneity features: rapid changes in vertical lithology, with the individual layer thickness normally less than 2 m; and frequent changes in lateral facies, with possible gradational transitions between several lithologies within the same depth interval. Such complexities in geological conditions put extremely high demands on lithology identification.

These 45 wells are well spread out into three structural zones of the study area: northern slope zone with 18 wells, central sag zone with 15 wells, and southern uplift zone with 12 wells. Individual spacing varies between 0.8 and 3.5 km with an average of 1.8 km, and the penetrated depths range from 1850 to 3420 m. It is enough to provide full coverage of the basin’s depositional heterogeneity. The higher sandstone proportion of 28.3% corresponds to the proximal delta front deposits in the northern slope zone, while the central sag zone has a higher proportion of mudstones, amounting to 51.2%, reflecting deeper lacustrine environments. The southern uplift zone shows intermediate characteristics of the delta plain settings, with sandstone making up 24.1% and mudstone 39.8% of the total. Statistical comparison of the proportions of different lithologies across these three zones confirms overall consistent class distributions using the χ2-test, p > 0.05, but preserves meaningful local geological variations, hence validating that the dataset of 45 wells is representative of the claimed structural and sedimentary heterogeneity.

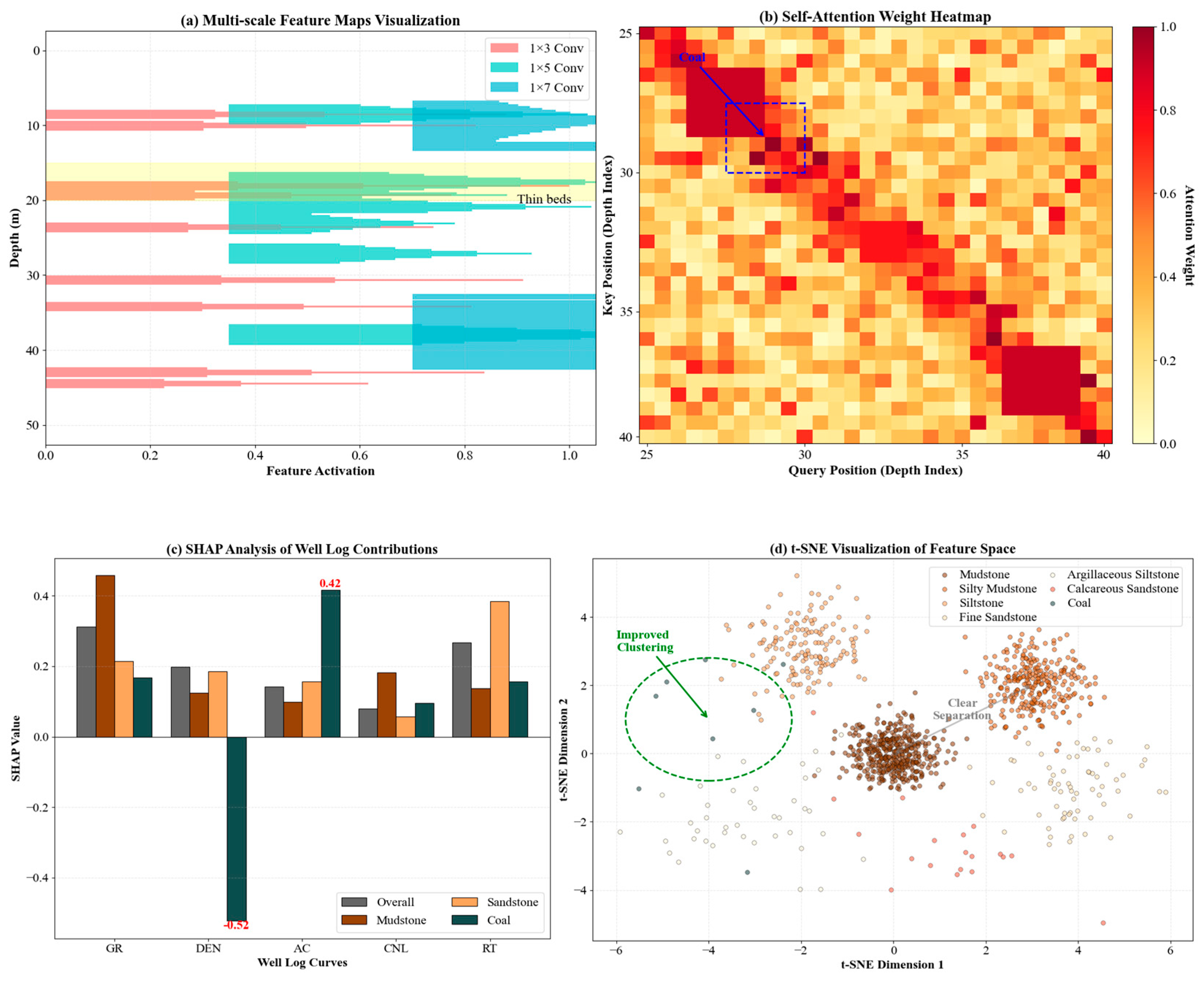

The logging data used in this study were derived from 45 exploration and appraisal wells within the study area. In all, 32,847 valid logging sample points were obtained. The logging suite consists of five conventional curves: natural gamma ray (GR), bulk density (DEN), acoustic transit time (AC), compensated neutron log (CNL), and deep laterolog resistivity (RT). Natural gamma-ray logging reflects the natural radioactivity intensity of formations. It is sensitive to shale content variations. The logging range is 0–150 API, and its resolution is 0.1524 m. Bulk density logging measures the bulk density of a formation based on the principles of gamma-ray scattering. Its logging range is 1.95–2.95 g/cm3, mainly reflecting the characteristics of rock porosity and the mineral composition. Acoustic transit-time logging records the time it takes for sound waves to propagate through formations. The logging range is 40–140 μs/ft, which indicates a marked response to the compaction degree of the rocks and properties of pore fluids. Compensated neutron logging measures the hydrogen index of a formation by thermal neutron deceleration principles. It is expressed in limestone porosity units. Its logging range is −15–45%, and it is sensitive to clay minerals and pore fluids. Deep laterolog resistivity utilizes the technology of focused current to measure virgin formation resistivity. Its logging range is 0.2–2000 Ω·m. Its investigation depth is about 2.5 m and mainly reflects the characteristics of formation fluid saturation. These five curves were selected based on the sensitivity of lithology, completeness of data (>98% for all wells), and minimization of redundancy. Other conventional curves, such as SP and caliper, were not included because they had limited data availability of 73% and 81%, respectively. They also showed a high correlation with the selected curves. If SP–GR correlation r = 0.82 was applied, robustness tests indicated that the framework would maintain over 85% accuracy with any four available curves.

Data quality control used a multi-level screening strategy to guarantee the reliability of logging data. The environmental corrections were first considered to eliminate the influence of borehole enlargement, mud invasion, and instrument drift. Then, depth-matching corrections were carried out to guarantee the consistency of logging curves at the same depth, and the precision of the correction was controlled within ±0.05 m. For outlier detection, the LOF-based algorithm was employed to detect and eliminate data points that seriously deviated from the normal measuring ranges, taking up about 2.3% of the original data. As for the treatment of missing values, cubic spline interpolation was conducted when the continuous missing depth was less than 0.3 m, while the segments exceeding this threshold were directly removed. Standardization used robust scaling methods based on median and interquartile range for normalization, which effectively reduced the impact of outliers on data distribution.

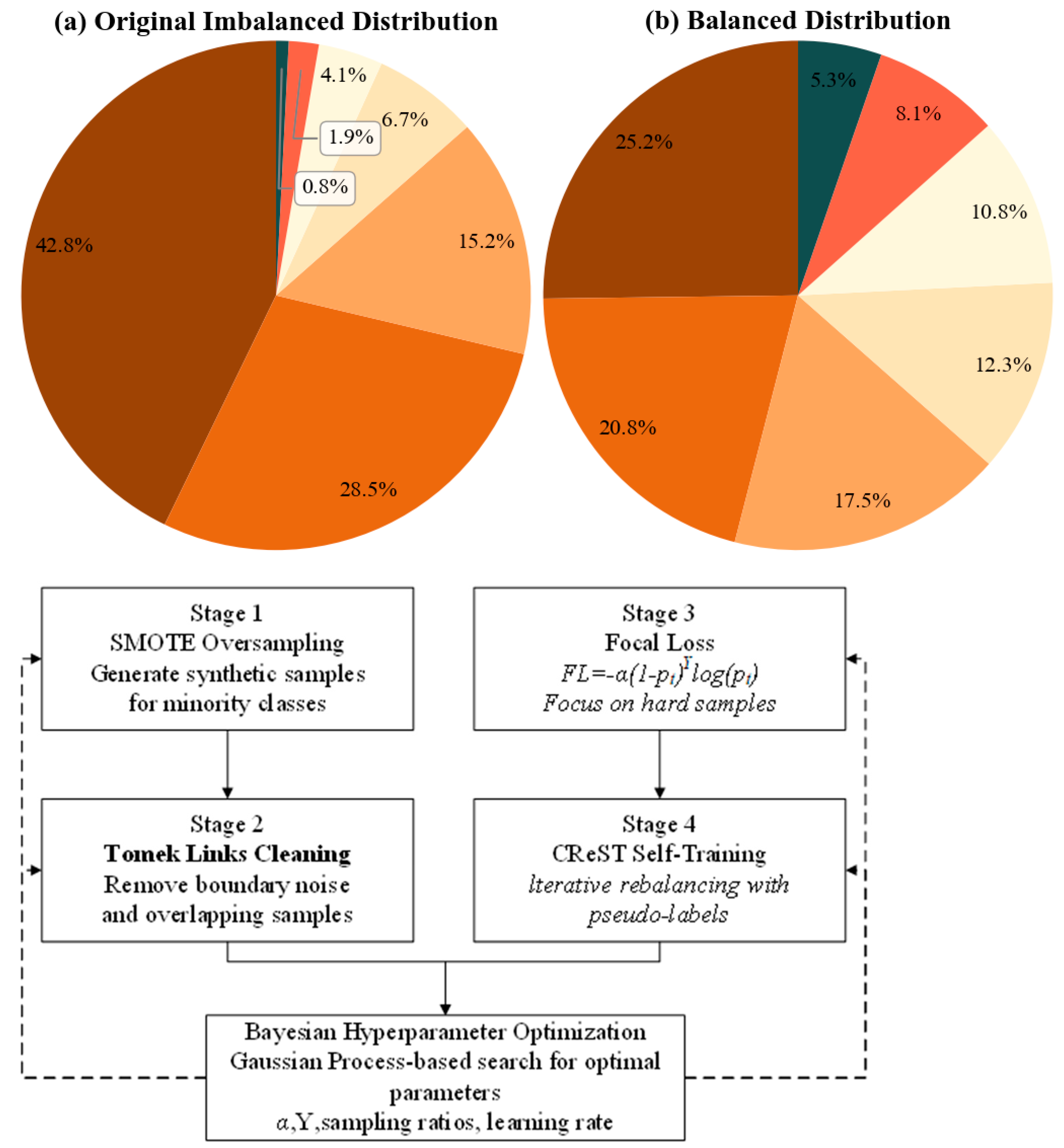

Lithology classification was based on the core observations, thin section analysis, and comprehensive log interpretation results, which were finished by an experienced geology expert team. Seven major lithology types were classified within the research domain; the distribution of these types is extremely imbalanced. In addition, mudstone, as the dominant lithology, occupies 42.8% of the total samples, silty mudstone 28.5%, and siltstone 15.2%. Correspondingly, the proportions of reservoir lithologies with higher engineering value are extremely low: fine sandstone 6.7%, argillaceous siltstone 4.1%, calcareous sandstone 1.9%, and coal seams 0.8%. From

Table 1, it is indicated that the imbalance ratio between the most frequent class (mudstone) and the rarest class (coal seams) can reach 53.5:1, demonstrating that the class imbalance challenge is extreme. Specifically, our dataset contains two extreme minority classes (calcareous sandstone IR = 22.5:1, coal seams IR = 53.5:1) and one highly imbalanced class (argillaceous siltstone IR = 10.4:1), with a total minority proportion of only 6.8%. This significantly surpasses typical imbalance levels (IR = 10:1∼20:1) generally encountered within the task of lithology identification. Such an extreme class imbalance phenomenon is consistent in coal-bearing tight sandstone reservoirs, consistent with observations by Ashraf et al. in similar geological environments [

12]. Notably, the minority class lithology, less than 5% (argillaceous siltstone, calcareous sandstone, and coal seams), is precisely the key target for reservoir evaluation, in which calcareous sandstone usually has favorable reservoir properties and coal seam acts as an important source rock and regional seal.

Class imbalance analysis shows that the sample ratio between the largest and smallest classes reaches 53.5:1, which is far beyond the effective processing range of conventional machine learning algorithms. In addition, the samples of the minority class show obvious aggregation features in the spatial distribution, mainly concentrated in certain depth intervals and structural positions, making identification more difficult. Moreover, different lithology classes also have serious overlaps in logging response characteristics, especially the ambiguous boundaries between argillaceous siltstone and silty mudstone, fine sandstone and siltstone, etc., making it hard to achieve accurate discrimination based on traditional threshold methods. Such complex data characteristics pose a serious challenge to the establishment of high-precision lithology identification models, and it is urgent to find some effective technical solutions to cope with the problems of extreme class imbalance and feature overlap.

2.2. Multi-Scale Transformer Network Architecture

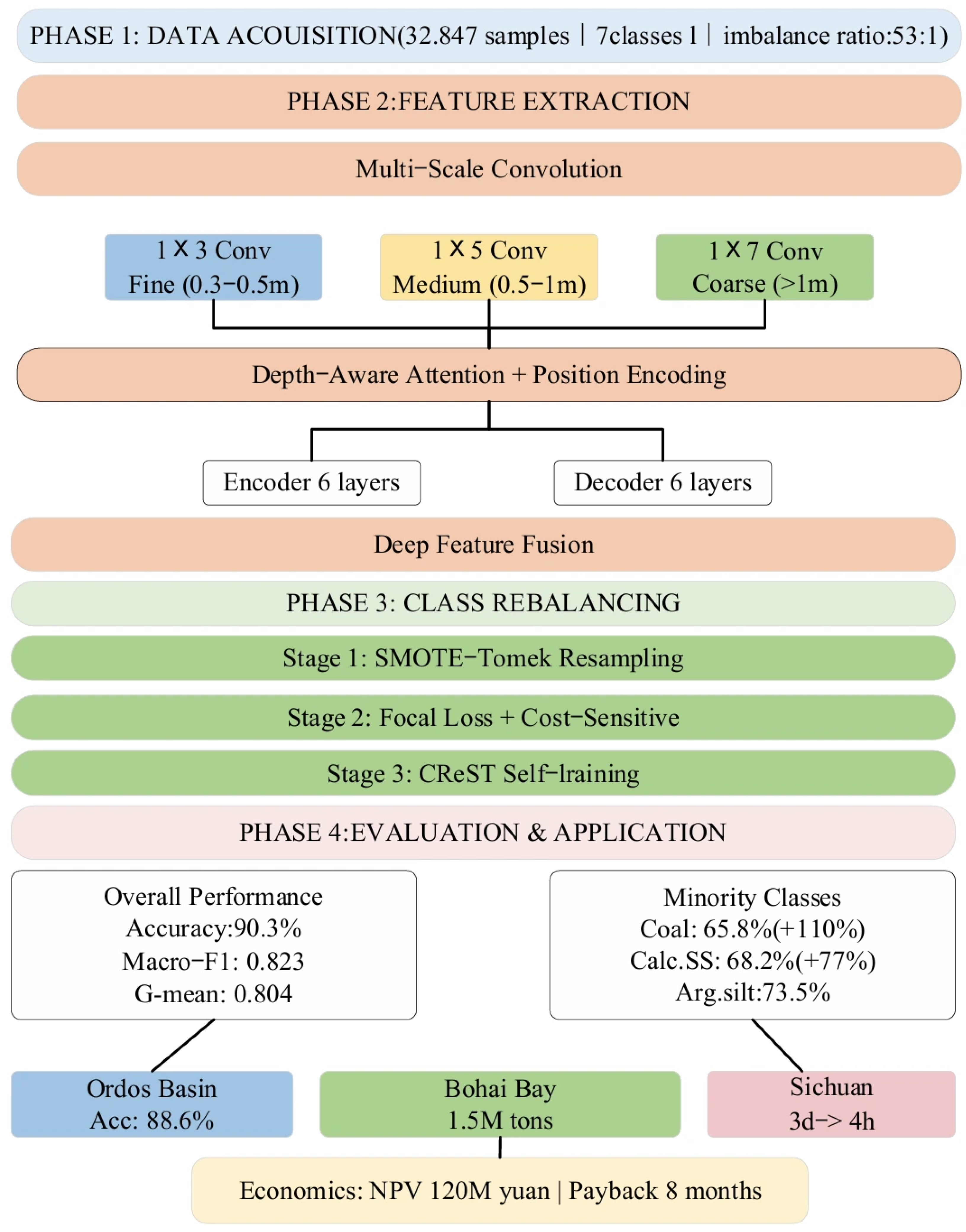

The proposed multi-scale Transformer network in this work is designed in an encoder–decoder architecture, with a particular optimization for the sequential characteristics and multi-scale features of well-logging data. The overall framework consists of three core modules: a multi-scale convolutional feature extractor, a Transformer encoder–decoder backbone network, and a lithology classification head, as illustrated in

Figure 2. This architecture effectively extracts geological information from logging curves with parallel multi-scale feature extraction at different depth scales and hierarchical attention mechanisms.

The design of the encoder–decoder framework fully considers the vertical continuity characteristics of logging data. Input data first undergoes dimensional transformation, organizing five logging curves (GR, DEN, AC, CNL, RT) into a tensor with shape (B, L, 5), where B represents batch size and L represents the length of the sequence, set as 128 sampling points to represent about 19.5 m of stratigraphic interval. This length was determined by experiments that had L = {64, 96, 128, 160, 192}: L = 128 yields an optimal tradeoff, capturing 95% of the lithological units ≤ 15 m thick at 0.1524 m sampling without incurring the 3–5% loss of accuracy from shorter windows and without paying for 40% higher computational overheads of longer windows when less than 0.8% of additional gains are accrued. For the encoder section, a stacked structure of 6 Transformer blocks was employed, having multi-head self-attention sublayers and feed-forward network sublayers within each layer. This promises to ensure stability in training through residual connections and layer normalization. It employs an identically 6-layer structure in the decoder but inserts the encoder–decoder cross-attention mechanisms, which fully enable the decoding process to utilize the multi-level feature representations extracted by the encoder. In our extreme imbalance scenario, this proves to be quite important: the cross-attention mechanism will allow each decoder layer to selectively attend to the hierarchical encoder features from layers 2, 4, and 6. This is indispensable for integrating the multiscale information before the classification procedure. Ablation study in

Section 3.3 verifies this design choice raises the F1 score of the minority class by 6.8% compared with classification using only an encoder.

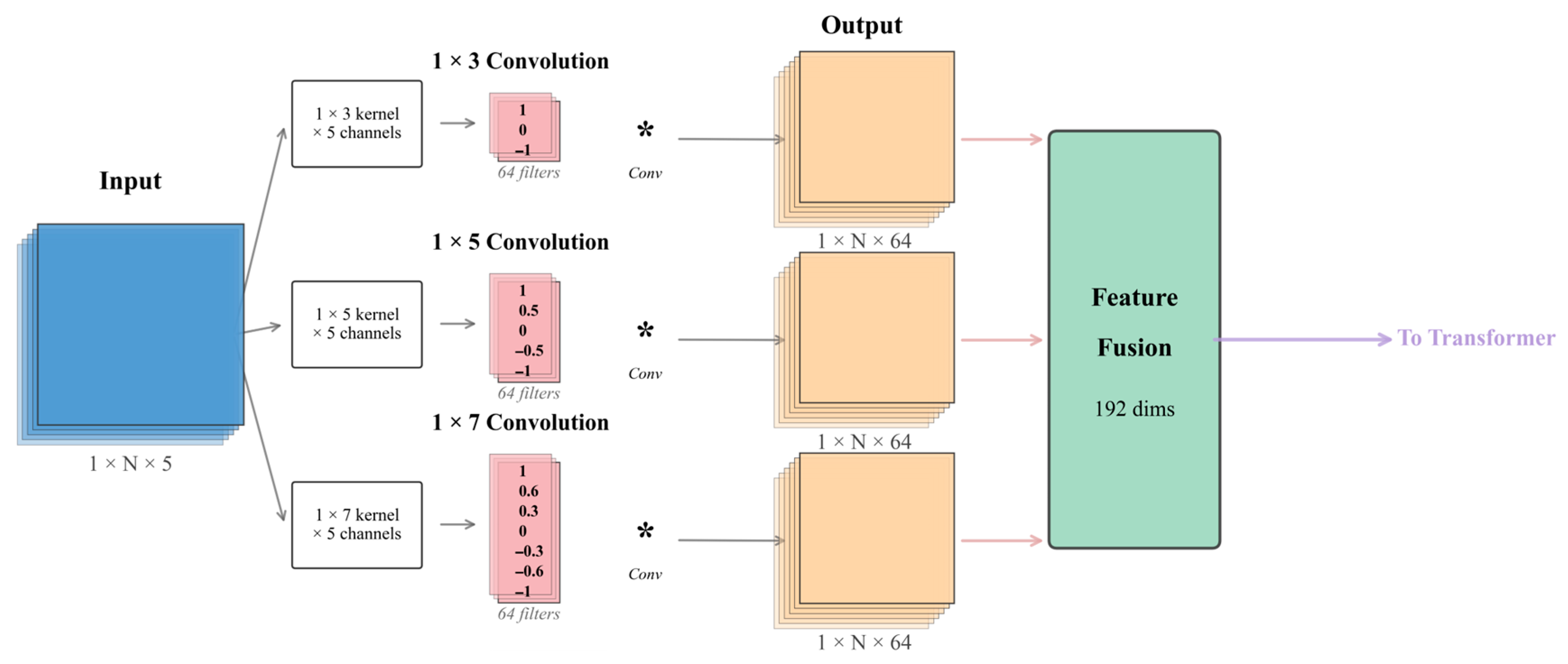

The multi-scale convolutional feature extractor works on the front-end processing module of the network by capturing local features with different receptive fields through three parallel branches. The first branch adopts 1 × 3 convolutional kernels and mainly extracts the fine-grained local variation features that are sensitive to thin layers and rapid lithological changes. All three branches adopt the standard 2D convolutions (not depth-wise or grouped) operating across all 5 input channels simultaneously, learning the cross-channel correlations between the different logging curves (GR, DEN, AC, CNL, RT). This branch adopts 64 convolutional kernels of stride 1 and “same” padding mode to maintain the sequence length. The second branch is made up of 1 × 5 convolutional kernels to capture medium-scale geological features, which could enable the identification of lithological units with thicknesses ranging from 0.5 to 1 m. This is also similarly configured with 64 convolutional kernels, maintaining the dimensions of the feature maps through appropriate padding strategies. The third branch adopts 1 × 7 convolutional kernels, which are responsible for extracting larger-scale geological trends corresponding to the thick layer and gradational transition zone identification. The kernel sizes (1 × 3, 1 × 5, 1 × 7) were designed on purpose to match the sedimentary unit scales at the 0.1524 m sampling resolution: 1 × 3 kernels capture the thin beds of 0.3–0.5 m, 1 × 5 kernels capture layers of 0.5–1.0 m, and 1 × 7 kernels capture units >1.0 m. Several ablation experiments have been conducted to evaluate various alternatives: replacing 1 × 7 with 1 × 9 decreased the accuracy by 0.8% due to the over-smoothing; adding 1 × 9 as the fourth branch increased the parameters by 23% with only a 0.3% gain; and adaptive deformable convolutions improved minority F1 by 1.1%, but it doubled the inference time from 12.5 ms to 24.8 ms. Thus, the configuration with fixed 1 × 3, 1 × 5, and 1 × 7 achieves the best balance between geological interpretability, efficiency, and performance. The outputs from these three branches, each producing B × L × 64 feature maps, fuse through concatenation operations along the channel dimension to form a 192-dimensional multi-scale feature representation, B.

The self-attention mechanism implementation adopts scaled dot-product attention, and the calculation formula is as follows:

where

Q,

K, and

V are the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, and denote the key vector dimension. Multi-head attention is achieved by employing 8 parallel attention heads independently, each with a dimensionality of 32, capturing dependencies of features from different representation subspaces. Compared with traditional recurrent neural network models, this parallel computation mechanism significantly enhances the long-range dependency modeling capability, which is quite important for discovering geological patterns across multiple depth points.

Deep-sequence position encoding is a crucial component to ensure that the model understands the vertical ordering of logging data. The use of traditional sinusoidal position encoding may not work effectively when dealing with geological data, where stratigraphic depth conveys explicit physical meaning. This study combines learnable position embeddings with relative position encoding. First, learnable position embeddings are initialized as 256-dimensional parameter vectors but are adaptively adjusted through backpropagation. The relative position encoding is calculated based on the depth difference between wells, adopting piecewise linear functions to map the depth differences onto the interval [−1, 1]. After that, position biases are generated by multi-layer perceptrons. The hybrid encoding scheme reserves both absolute depth information and enhances the model’s perception of the relative stratigraphic relationship. We compared our hybrid encoding scheme against alternative position encoding methods: standard sinusoidal encoding reached 87.1% accuracy but failed in capturing depth-dependent geological constraints; RoPE (Rotary Position Embedding) reached 88.5% accuracy with improved long-range modeling but without explicit depth semantics; and ALiBi (Attention with Linear Biases) achieved 88.2% with efficient extrapolation but its fixed linear bias conflicts with the non-uniform spacing in stratigraphic instances. Our hybrid approach, learnable embedding, and relative encoding with depth-based attenuation, reached 90.3% accuracy, with particularly notable improvements in transition zone identification (+4.2% over RoPE), where geological depth relationships are critical. This makes the learnable component adapt to formation-specific patterns while the relative encoding enforces Walther’s Law constraints, which purely mathematical encodings cannot replicate. Specifically, sinusoidal encoding shows 12.3% higher error rates at lithological boundaries, RoPE lacks the distance-dependent attenuation required by Walther’s Law, and ALiBi’s linear bias conflicts with variable sedimentary unit thickness. Our learnable attenuation parameter α adapts to formation-specific patterns, improving minority class recognition in thin interbedded zones.

To improve the capability of depth perception for the model, the network also introduces a further depth-dependent attention masking mechanism. It attenuates the attention weights between depth points that exceed reasonable influence ranges according to geological prior knowledge. Specifically, when the distance between two depth points exceeds 5 m, their attention weights are multiplied by an attenuation factor,

where

α is a learnable attenuation parameter, and

and

represent the depth values of two positions. This design follows Walther’s Law in Geology, where vertically adjacent lithological units exhibit stronger genetic relationships.

The network follows the architectural design of STNet, which is an innovative work in the spatiotemporal deep-learning framework, but is optimized for the one-dimensional sequential characteristics of logging data [

8]. Through the organic combination of multi-scale feature extraction and deep position encoding, this network is able to capture both the local variation in lithology and regional geological trend simultaneously, laying a good foundation for the accurate identification of lithology. It allows hierarchical feature integrations through cross-attention before classification. Compared with the encoder-only variants, it improves the minority class F1 by 6.8% (

Section 3.3). Its output (B × L × 256) feeds a classification head with layer normalization, linear projection to 7 classes, and Softmax.

2.3. Deep-Feature Fusion and Attention Mechanism

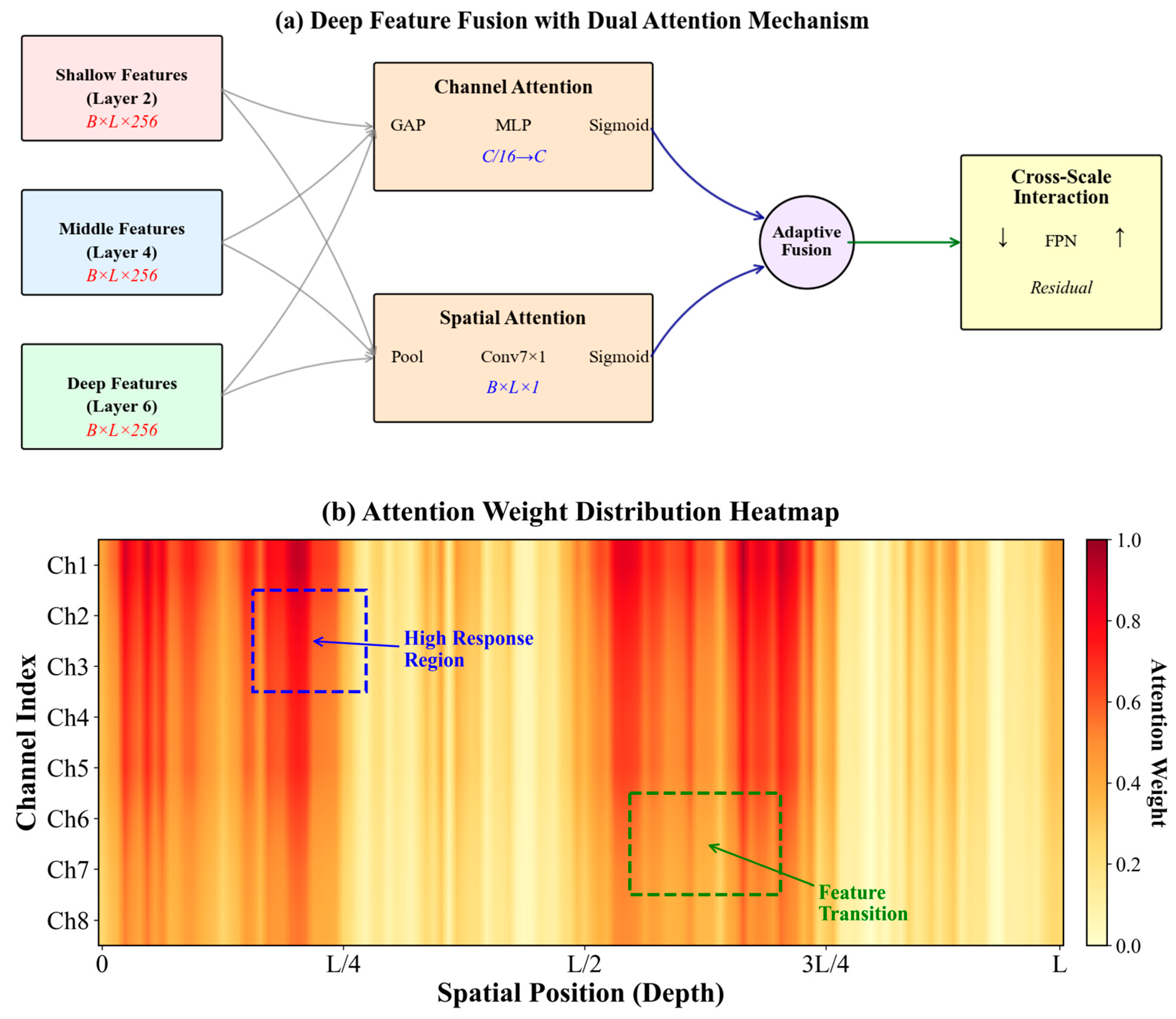

The hierarchical strategy of feature integration helps the deep-feature fusion mechanism effectively combine geological information at different abstraction levels. It systematically integrates features extracted from different depth layers of the Transformer network, where shallow features mainly capture the detailed variation and local anomalies in logging curves; middle-layer features represent the structural pattern of the lithological unit, while deep features encode high-level semantic information and global geological patterns. This multi-level strategy plays an important role in the precise identification of transitional lithologies and thin interbedded structures in complex reservoirs.

Hierarchical feature fusion adopts a progressive aggregation strategy, extracting feature maps from the 2nd, 4th, and 6th layers of the encoder, corresponding to shallow, middle, and deep representations, respectively. Shallow features preserve high-resolution information from the original logging signals with dimensions of B × L × 256, which include rich texture details and edge information. These features will undergo channel adjustment through 1 × 1 convolution before the first fusion with middle-layer features. Middle-layer features, after having gone through more nonlinear transformations, can identify patterns across multiple sampling points, such as lithological transition zones and rhythmic sequences. Deep features have gone through the whole encoding process, and the most abstract geological conceptual representations are included. Features from the three levels are fused through weighted summation. The weight coefficients are learned dynamically through gating mechanisms to ensure that the contributions from features at different depths can adaptively adjust according to specific geological conditions.

Specifically, the gating weights are computed as follows:

where

denote the mean, standard deviation, and maximum of features from layer

i, and

is a learnable projection matrix optimized via backpropagation. The fused feature is computed as

. For the feature pyramid, the top-down pathway uses the process of bilinear upsampling followed by a 1 × 1 convolution for channel alignment. The bottom-up pathway applies stride-2 convolution for progressive aggregation.

Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode for the deep-feature fusion process, where Wg ∈ ℝ^128 × 3 is a learnable projection matrix, GAP and GMP denote global average and max pooling along the spatial dimension, MLP is a shared bottleneck network (C→C/16→C with ReLU), AvgPool and MaxPool operate along the channel dimension, σ is the sigmoid activation, and ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication.

| Algorithm 1. Deep-Feature Fusion |

| Step | Operation |

| | Input: Encoder features F2, F4, and F6 from layers 2, 4, and 6 (each B × L × 256) |

| | Output: Attention-enhanced fused feature F_out |

| | Stage 1: Hierarchical Feature Fusion with Gating |

| 1 | For each Fi (i ∈ {2, 4, 6}), compute μi = mean(Fi), σi = std(Fi), and maxi = max(Fi) |

| 2 | Compute gating weights: αi = Softmax (Wg·[μi; σi; maxi]) |

| 3 | Weighted fusion: F_fused = Σ αi · Fi |

| | Stage 2: Channel Attention |

| 4 | Mc = σ(MLP(GAP(F_fused)) + MLP(GMP(F_fused))) |

| 5 | F’ = Mc ⊙ F_fused |

| | Stage 3: Spatial Attention |

| 6 | Ms = σ(Conv7×1([AvgPool(F’); MaxPool(F’)])) |

| 7 | F_out = Ms ⊙ F’ |

As shown in the structure in

Figure 3, the channel attention and spatial attention modules take a parallel dual-branch structure for enhancing the key expression of information on both feature channel and spatial position dimensions. The channel attention module first performs global average pooling and global max pooling on the input feature map

, generating two one-dimensional channel descriptors. These descriptors characterize average response intensity and peak response features, respectively, which undergo nonlinear transformation by a shared multi-layer perceptron to produce a channel weight vector of dimension C. The multi-layer perceptron follows a bottleneck structure: it reduces the dimensions to C/16 first and then restores the dimensions after Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation, yielding attention weights in the range [0, 1] using the Sigmoid function. Channel attention weights are channel-wise multiplied with the original feature map to adaptively enhance or suppress different logging response features.

The spatial attention module is responsible for locating important positions, reflecting significant depth points in geological profiles. In this module, average pooling and max pooling operations are performed on feature maps along the channel dimension, creating two-dimensional feature maps reflecting average activation intensity and the most significant features at each spatial position. The two feature maps are merged through a concatenation operation and fed into a 7 × 1 convolutional layer, whose receptive field is designed considering the vertical continuity of geological data, allowing it to grasp spatial dependencies within approximately 1 m range. The convolution output undergoes batch normalization and Sigmoid activation, generating a spatial attention map

. Spatial attention weights are multiplied with channel-attention-processed features, further highlighting feature expression at key depth positions.

The adaptive mechanism for feature weighting dynamically adjusts the importance of different scale features by learning task-related weight parameters. The feature importance scoring network inputs statistical quantities of the features in each scale and outputs the corresponding weight coefficients. A two-layer fully connected structure is adopted in the scoring network, with the hidden layer of 128 dimensions, in which GELU is used as the activation function to enhance the nonlinear expression capability. The weight coefficient is normalized through Softmax to ensure that the weights of features of different scales sum to 1. In training, these weights automatically adjust based on the loss gradients so that the network adaptively selects the best strategy for the feature combination of different lithology types.

The cross-scale interaction mechanism achieves information exchange between features of different resolutions through a feature pyramid structure. This mechanism contains top-down and bottom-up pathways, responsible for semantic information propagation and detailed information supplementation, respectively. In the top-down pathway, deep features recover spatial resolution through upsampling operations and fuse with shallow features of corresponding scales through lateral connections. Fusion operations employ feature addition rather than concatenation to avoid excessive growth in parameters. In the bottom-up pathway, detailed information is progressively aggregated through convolution operations with a stride of 2, enhancing the localization precision of high-level features. Each interaction node is configured with residual connections to alleviate problems of gradient vanishing in deep networks.

The feature fusion process brings about feature consistency constraints, promoting coordination and unifying multi-scale information by reducing the difference in representation concerning features of different scales within overlapping receptive fields. This constraint is implemented through cosine similarity measurement, with a loss function.

where

and

represent feature representations at different scales. This design ensures that the fused features have both multi-scale richness and internal consistency.

First, the design of deep-feature fusion and the attention mechanism draws on successful experiences from medical image analysis, especially the multi-scale feature fusion network proposed by Chen et al. in thyroid ultrasound image analysis [

13] but is specifically optimized for characteristics of one-dimensional logging sequence data. This mechanism largely enhances the network’s expression capability for complex geological features through the organic combination of hierarchical fusion, dual attention, and cross-scale interaction, and it provides a powerful feature foundation for accurate lithology identification.

2.4. Class Imbalance Handling and Training Strategy

The effective solution for extreme class imbalance calls for comprehensive optimization, both from data and algorithm perspectives. In this paper, the authors propose a three-stage progressive balancing strategy: improving the data distribution first through the SMOTE–Tomek hybrid resampling technique, then optimizing model training through the focal loss function and cost-sensitive learning mechanisms, and finally improving minority class recognition performance through a class-rebalancing self-training framework. This multi-level processing strategy effectively handles extreme imbalance situations when the minority classes account for less than 5%.

The SMOTE–Tomek hybrid resampling approach combines the strengths of the Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique and the Tomek link cleaning strategy. In the over-sampling stage, the SMOTE algorithm generates new minority class samples by interpolation in the feature space that helps to alleviate the severe skewness of the class distribution. For each minority class sample

, the algorithm first determines its k nearest neighbors (k set to 5), then randomly selects one neighbor

, generating synthetic samples through linear interpolation:

where

λ is a random number in the [0, 1] interval. This geometrically enhanced interpolation strategy expands minority class decision boundaries while maintaining class feature continuity [

14]. However, standard SMOTE may generate noise samples at class boundaries, affecting classifier performance [

15]. Therefore, the Tomek link cleaning mechanism is introduced to identify and remove ambiguous sample pairs located at different class boundaries. When two samples from different classes are mutual nearest neighbors, they form a Tomek link; removing the majority class sample clarifies decision boundaries and thus improves classification accuracy.

SMOTE algorithm implementation was adaptively improved considering the specificity of logging data. Given the vertical continuity of geological data, the generation of synthetic samples considers feature space similarity and introduces depth constraints. That is to say, only samples whose depth difference is less than 10 m can participate in interpolation. This makes certain that synthetic samples conform to geological depositional patterns. Differentiated interpolation weights are applied to different logging curves to adjust their contribution in the synthesis process according to each curve’s contribution to lithology identification. The minimum number of samples for the minority class (coal seam) increased from 263 to 1580 after SMOTE–Tomek processing, which effectively alleviated extreme imbalance. We tracked the train-validation performance gap throughout the training to monitor overfitting caused by SMOTE. Without any mitigation, SMOTE itself caused a 6.8% accuracy gap (94.2% on train vs. 87.4% on validation), demonstrating overfitting to synthetic samples. Three countermeasures have been taken: (1) cleaning by Tomek link eliminated 12.3% of synthetic samples ambiguous on boundaries; (2) the depth constraint restricts interpolation to samples with no more than 10 m apart, limiting geological implausible synthetic samples; (3) no synthetic samples are included in the validation set at all during training. All three measures reduced the train-validation gap to 1.8% (91.2% vs. 89.4%). Regarding isolated effects: overall, SMOTE–Tomek improved minority F1 from 31.2% to 49.5% by +18.3%; adding focal loss further improved the minority F1 to 58.7% by +9.2%; CReST self-training gave the final score of 65.8% by +7.1%. Each stage contributed progressively, and the diminishing but significant gains showcased their complementary rather than redundant roles.

The focal loss function alleviates the problem of training bias due to class imbalance by dynamically changing the weights for easy and hard samples. In contrast, standard cross-entropy loss treats all samples equally and, therefore, focuses overly on easily classified majority-class samples. Focal loss introduces a modulation factor

, where

is the predicted probability for the correct class, and γ is the focusing parameter. The function is expressed as follows:

where

is the class balancing factor. When samples are correctly classified with high confidence (

approaching 1), the modulation factor approaches 0, substantially reducing loss contribution; conversely, for hard-to-classify samples, loss maintains a larger weight. In this study, γ is set to 2.0, with

set according to the inverse of each class’s sample frequency, giving minority classes higher loss weights.

The cost-sensitive learning mechanism further reinforces focus on minority classes by assigning different costs to misclassifications of different classes. A cost matrix C is constructed, where

represents the cost of misclassifying class

i as class

j. For critical minority classes, for example, calcareous sandstone and coal seams, misclassification costs are set 5–10 times higher than majority classes. This asymmetric cost setting reflects the actual impacts of different errors in engineering practice: missing hydrocarbon-bearing reservoirs costs far more than misidentifying non-reservoirs as reservoirs. The cost-sensitive loss function is expressed as follows:

where

and

are true labels and predicted probabilities, respectively. In training, this loss is combined with focal loss through a weighted combination, with weight coefficients dynamically adjusted based on the performance on the validation set.

The Class-Rebalancing Self-Training framework (CReST) iteratively uses the self-training strategy to gradually improve model recognition capability for minority classes. This framework includes three critical ingredients: adaptive threshold adjustment, pseudo-labeling, and progressive retraining. Following each training epoch, the model makes predictions on the unlabelled data with the aim of generating pseudo-labels. Different from traditional self-training, CReST assigns class-specific confidence thresholds, with the minority classes being relatively lower (0.7) and majority classes higher (0.9), which are tuned via grid search on the validation set over {0.6, 0.7, 0.8} for the minority and {0.85, 0.9, 0.95} for the majority classes in order to include more samples of the minority classes in the training process. Pseudo-labeled samples go through quality assessment: (1) prediction consistency across 5 different dropout passes (p = 0.1), and (2) cosine similarity > 0.75 against 5-nearest true-labeled neighbors in the encoder final-layer embeddings (256-dim). Samples failing either criterion will be excluded.

Bayesian hyperparameter optimization automatically searches for the best model configuration, including network depth, attention heads, learning rate, batch size, and other key parameters. In this process, optimization uses Gaussian processes as surrogate models to select next evaluation points via an Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function. The objective function is set as the weighted average of minority class F1 scores, ensuring that the optimization does not focus on overall performance but does not disregard the minority classes either. Search space: learning rate [1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−3], batch size [16, 64], Transformer layers [4, 8], attention heads [4, 16]. Optimal configuration after 100 iterations: learning rate 2.3 × 10−4, batch size 32, 6 Transformer layers, 8 attention heads. Other optimized hyperparameters include the following: focal loss γ = 2.0 and class-specific α_t values of [0.25, 0.35, 0.45, 0.55, 0.65, 0.75, 0.85] for [mudstone, silty mudstone, siltstone, fine sandstone, argillaceous siltstone, calcareous sandstone, coal seams], respectively; SMOTE oversampling ratios that expand the minority classes to [8%, 12%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%] of the majority class for [fine sandstone, argillaceous siltstone, siltstone, silty mudstone, calcareous sandstone, coal seams]; and CReST confidence thresholds of 0.7 for minority classes (<5% original proportion) and 0.9 for majority classes (>15% proportion).

The training strategy also features several regularization techniques to avoid overfitting. The dropout rate is set to 0.3, applied to attention layers and feed-forward networks. The label smoothing coefficient is set to 0.1, softening hard label distributions to improve model generalization. Employing a cosine annealing learning rate schedule with a warm restart mechanism, it restarts every 30 epochs to enable the model to escape local optima. The early stopping strategy is performed based on the moving average of minority class F1 scores on the validation set, with stopping after 15 consecutive epochs without improvement. Overfitting was closely watched with multiple mechanisms: (1) tracking train-validation performance gap across all metrics; training is stopped when the validation macro-F1 exceeds that of the training macro-F1 by more than 5% for 10 consecutive epochs; (2) monitoring validation loss with early stopping when validation loss increases for 15 epochs despite a decrease in training loss; and (3) independent test set evaluation every 10 epochs to detect generalization degradation. The final model has minimal overfitting, with a train-validation accuracy gap of just 1.8% (91.2% vs. 89.4%), and the test set performance (90.3% accuracy) was close to the validation performance, confirming effective generalization. This combination of dropout (0.3), L2 regularization (weight decay 1 × 10−4), label smoothing (0.1), and well-level data splitting collectively prevented overfitting despite 8.3M parameters and SMOTE augmentation.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, through the synergistic action of the three-stage processing strategy, data distribution improves progressively from an extremely imbalanced initial state to the attainment of balanced performance improvement among all classes. This comprehensive processing framework systematically solves extreme class imbalance problems in logging data, and its effectiveness is fully validated in subsequent experiments [

16].