A Comprehensive Mathematical Model for the Estimation of Solar Radiation and Comparative Analysis in Greenhouses with Two Distinct Geometries and Covering Materials: Case Study in Psachna, Evia, Greece

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objective

1.2. Novelty—Innovation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Greenhouse’s Characteristics

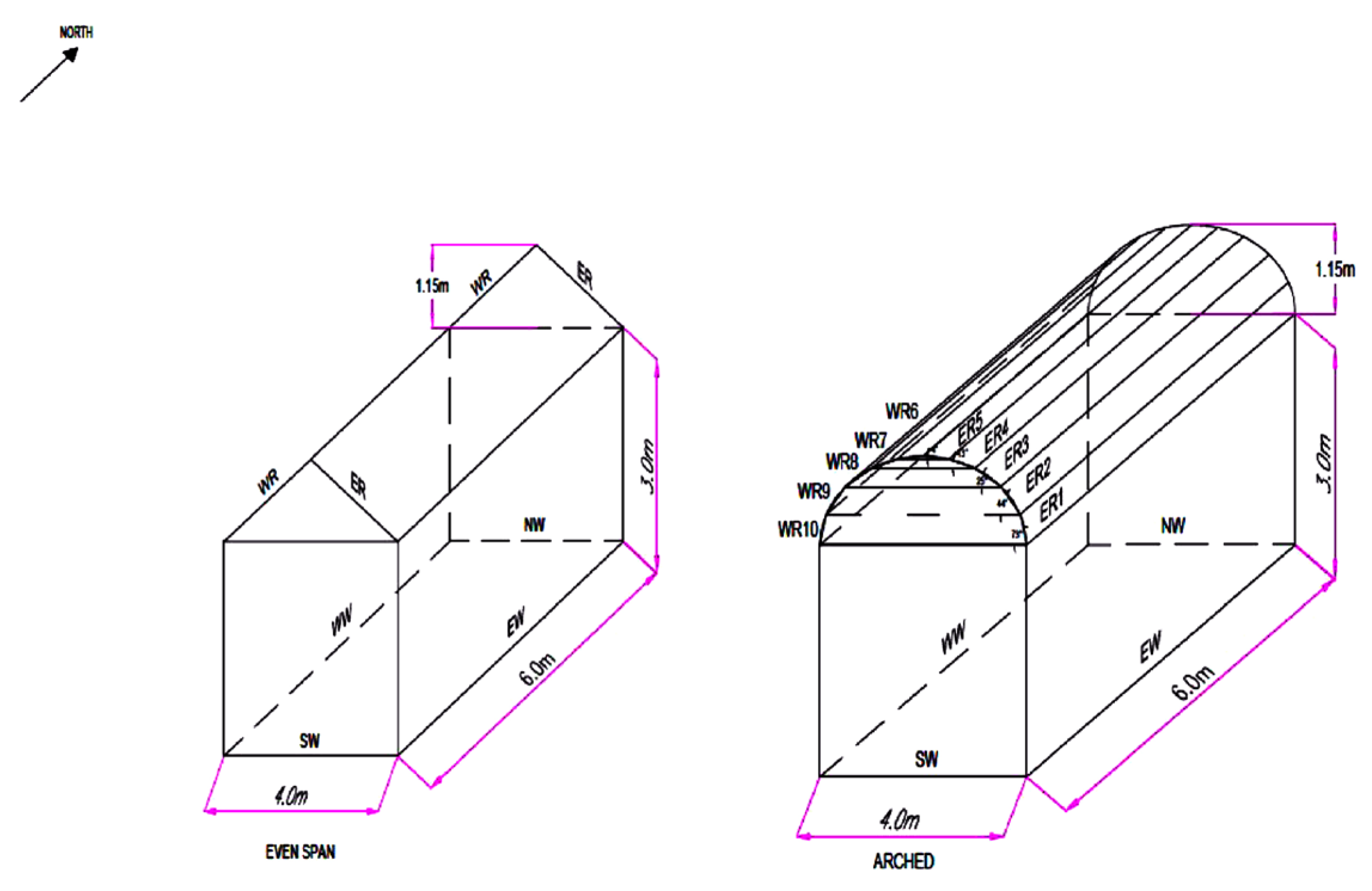

2.1.1. Greenhouse’s Geometry

2.1.2. Greenhouse’s Cover Material

2.2. Description of Modelled Greenhouses

2.2.1. Climatic Classification

2.2.2. Geometry and Covering Material

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Methodology Analysis

2.3.2. Calculating Solar Angles

2.3.3. Calculation of Radiation

Coefficients for Solving Radiation

Direct Radiation on a Horizontal Surface

Diffuse Radiation on a Horizontal Surface

Total Radiation on a Horizontal Surface

Direct Radiation on an Inclined Surface

Diffuse Radiation on an Inclined Surface

Total Radiation on an Inclined Surface

Slope Factors

Reflected Ground Radiation

- The ground is considered as a pure diffusion surface

- The variation in the properties of transparent materials is not taken into account, and

- The environment around the solar greenhouse is considered as having its own reflectivity

Factors for Solving Atmospheric Radiative Transmission

Components for Calculating Radiation Transmission

Transmittance

Radiant Transmission

Components to Calculate Radiation Absorption

Absorptivity

Radiation Absorption

Sunshine

3. Results

3.1. Presentation of Meteorological Data

3.1.1. High Temperatures & Low Temperatures

3.1.2. Global Radiation (

3.1.3. Total Radiation on a Horizontal Surface (

3.1.4. Direct Radiation on Horizontal Surface (

3.1.5. Sunshine (Diffuse Fraction )

- The climatic conditions in the Psachna area of Evia (with coordinates ) are favourable for greenhouse crops due to the area’s abundant solar energy, particularly during the warmer months

- The low radiation and temperature levels during winter necessitate the implementation of supplementary heating and lighting systems

- The significant fluctuations in daily and seasonal temperatures and solar radiation underscore the need for effective control systems for greenhouse cultivation

- Direct radiation () plays a vital role in photosynthesis, particularly when greenhouse surfaces are clean and well-oriented

- Conversely, while diffuse light () aids in light penetration into the deeper layers of foliage, an excessive amount may indicate suboptimal sunlight conditions

3.2. Presentation of Radiation Results Not Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Covering Material

3.3. Presentation of Radiation Results Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Covering Material

4. Discussion

- This section analyses meteorological data by incorporating high and low temperatures for each hour of the day. Understanding these temperatures is crucial, as the outside temperature has a significant impact on the temperature inside the greenhouse throughout the entire 24-h period.

- In the previous section, the results of all radiation measurements for a full 24-h day were presented, highlighting the negative radiation values recorded from sunset to sunrise, during the hours when there is no sunlight. This section will focus specifically on the results for the hours between sunrise and sunset, which vary by month. The discussion will explain the occurrence of negative radiation values during daytime hours that receive sunlight.

- The calculation of radiation is followed by a separate paragraph addressing the duration of sunshine and the diffuse fraction. The commentary for these calculations focuses solely on the values obtained from sunrise to sunset, which also vary throughout the year.

- For the commentary on the radiation results, hours from sunset to sunrise are not considered. To ensure accuracy, each month’s sunset and sunrise times were evaluated separately. However, any values recorded as negative during the hours from sunrise to sunset are not eliminated. In most studies, negative values are typically excluded or set to zero in subsequent calculations and analyses. In this work, to provide a more accurate representation, these negative values are included and justified.

- Negative radiation values may indicate either a calculation error or necessitate an interpretation suggesting these values are likely related to shading or counter-radiation effects. After verifying the correctness of the calculation equations and confirming the lack of shading based on the selected location (evident through Google Maps), coupled with the radiation calculations based on solar angles, it is evident that the appearance of negative values is caused by the opposite radiation flow and the differences arising from a 90° inclination to the sun’s position. The models selected for this study to calculate solar radiation are based on solar angles.

- Some equations concerning the calculation of direct radiation rely on the angle of incidence . When , , resulting in negative values for direct radiation in these cases. A indicates that the sun is obscured behind the surface.

- Negative values may also occur in the absence of solar radiation, such as during cloudy skies.

- While negative values as a description of a physical quantity are not typically “normal,” they are mathematically legitimate and can be justified within the context of solar movement and the relationship between radiation and surface orientation.

4.1. Meteorological Data

4.1.1. Distribution of Temperatures Compared to Normal

4.1.2. Temperature Picture of the Area

4.1.3. Global Radiation (, Direct (, Diffuse ( and Total ( Radiation in a Horizontal Surface

4.1.4. Correlation Between Radiation and Local Temperatures

4.1.5. Sunshine (Diffuse Fraction )

4.2. Radiations Not Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Greenhouse Covering Material: Radiation on an Inclined Surface and Reflected Radiation (Supplementary Materials S3, Tables S8 and S9)

- This includes the direct, diffuse, and total radiations on an inclined surface, as well as the reflected radiation (ground, direct, diffuse, and total)

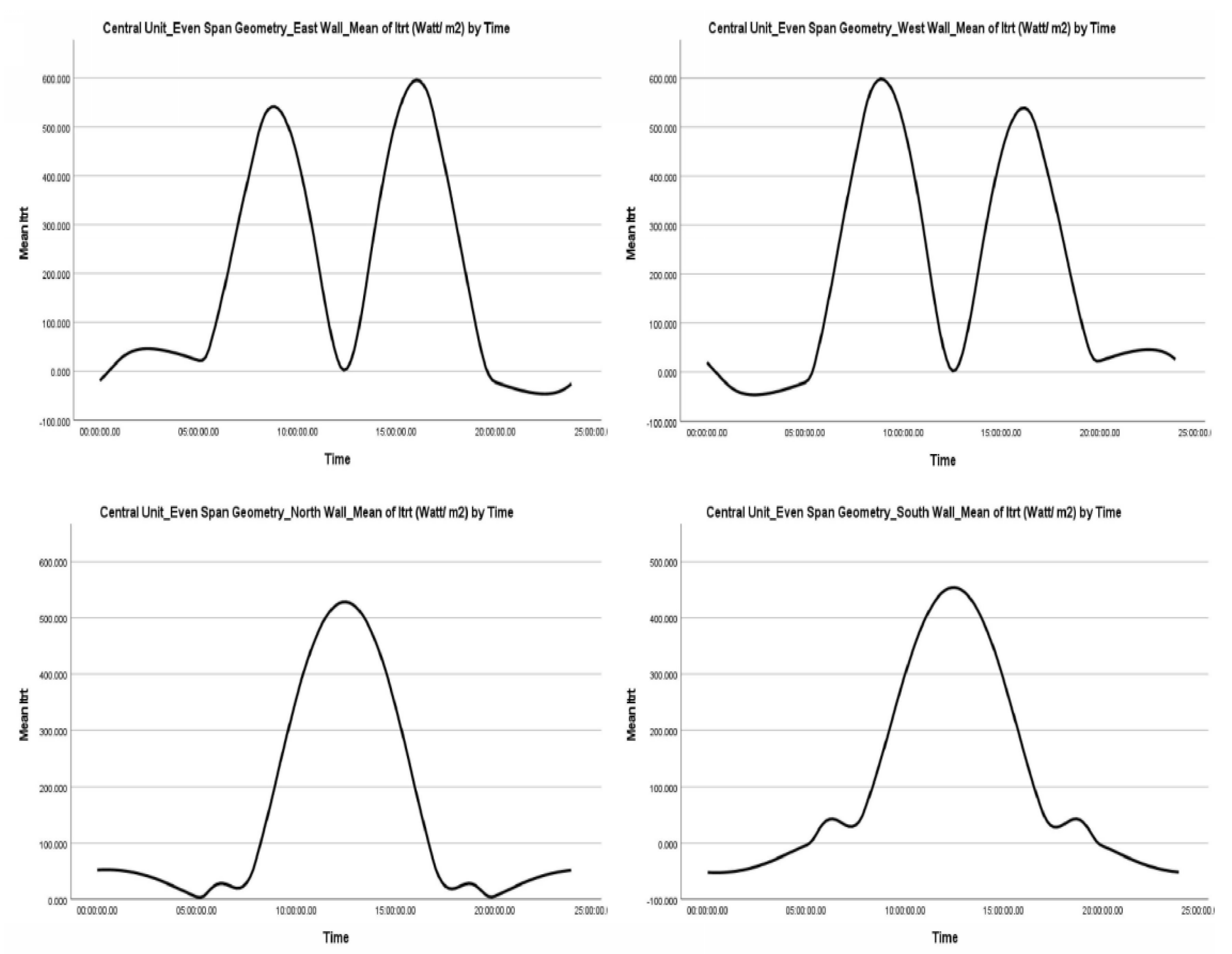

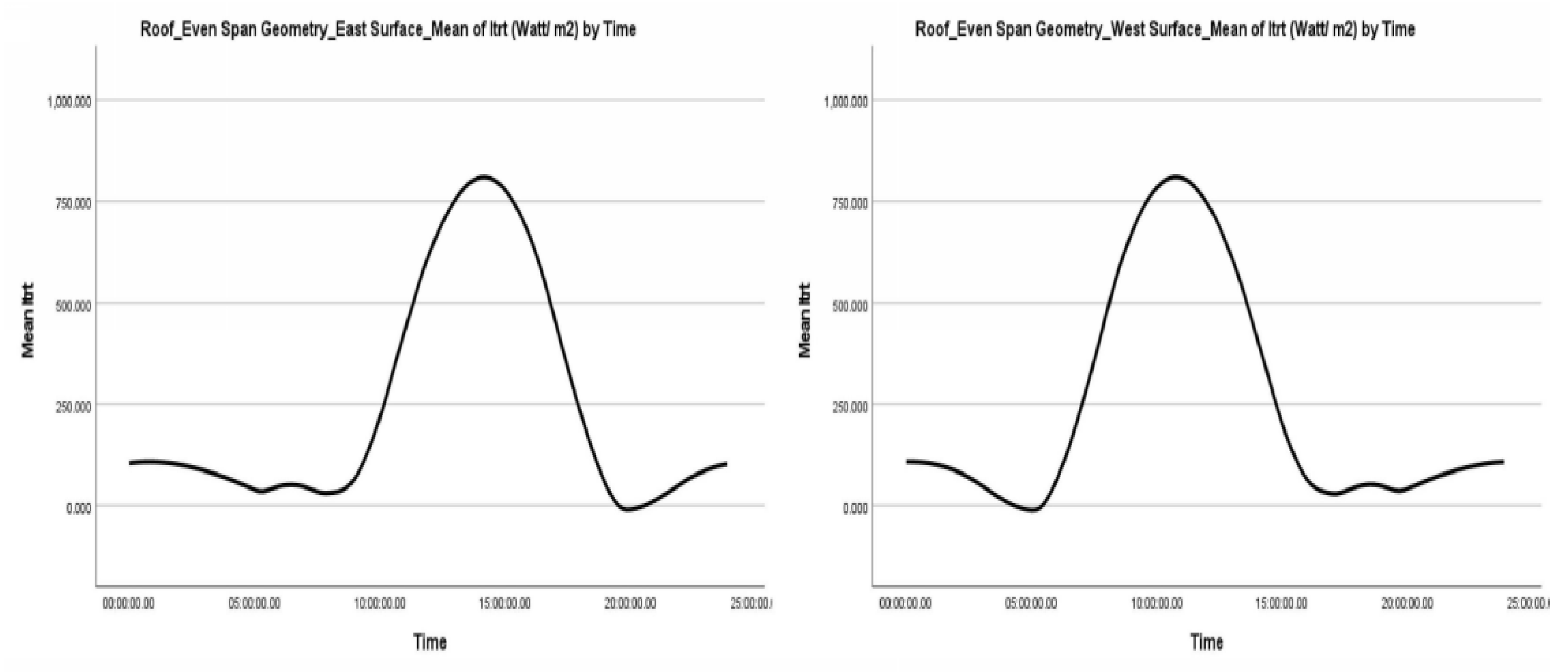

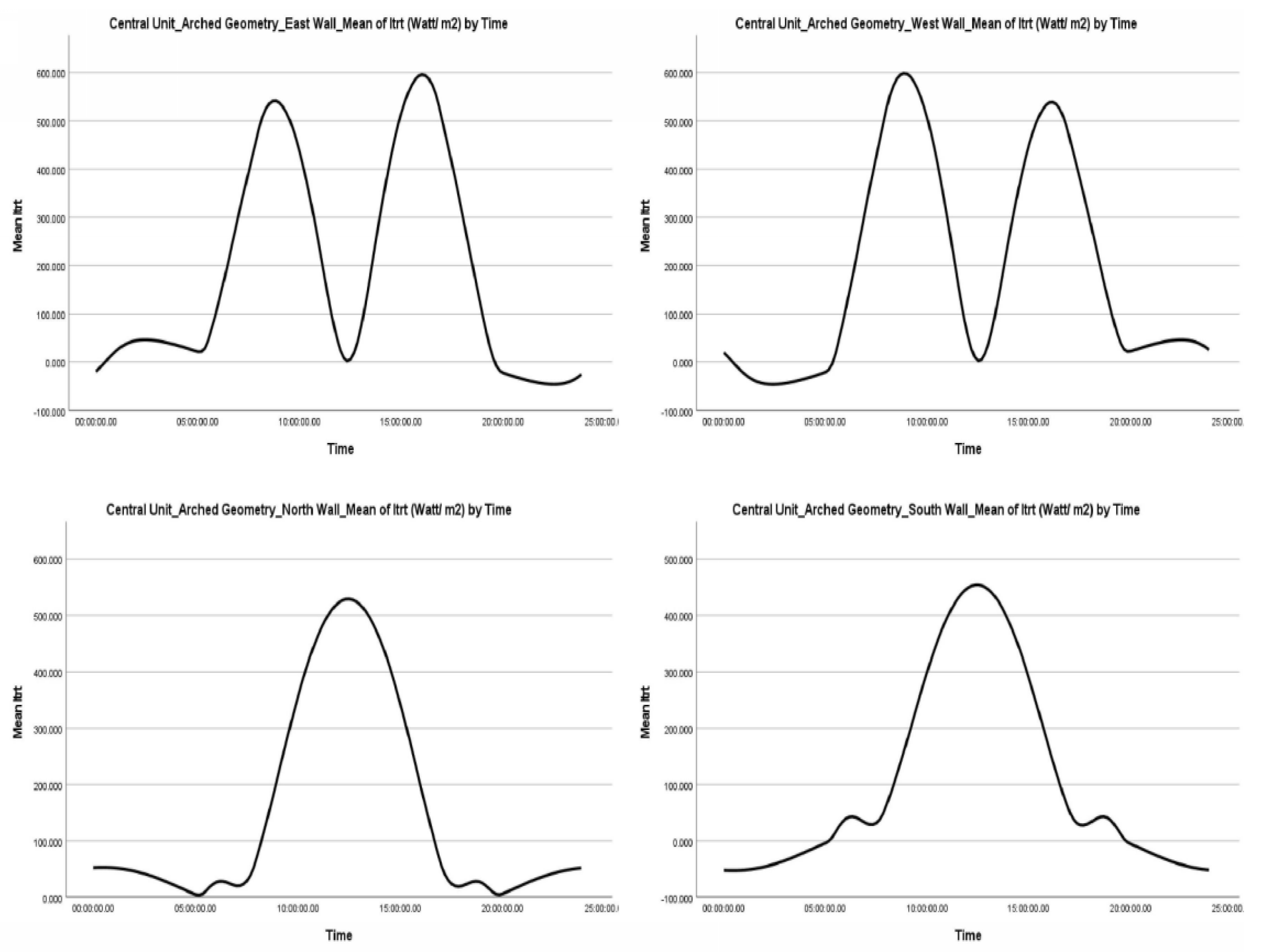

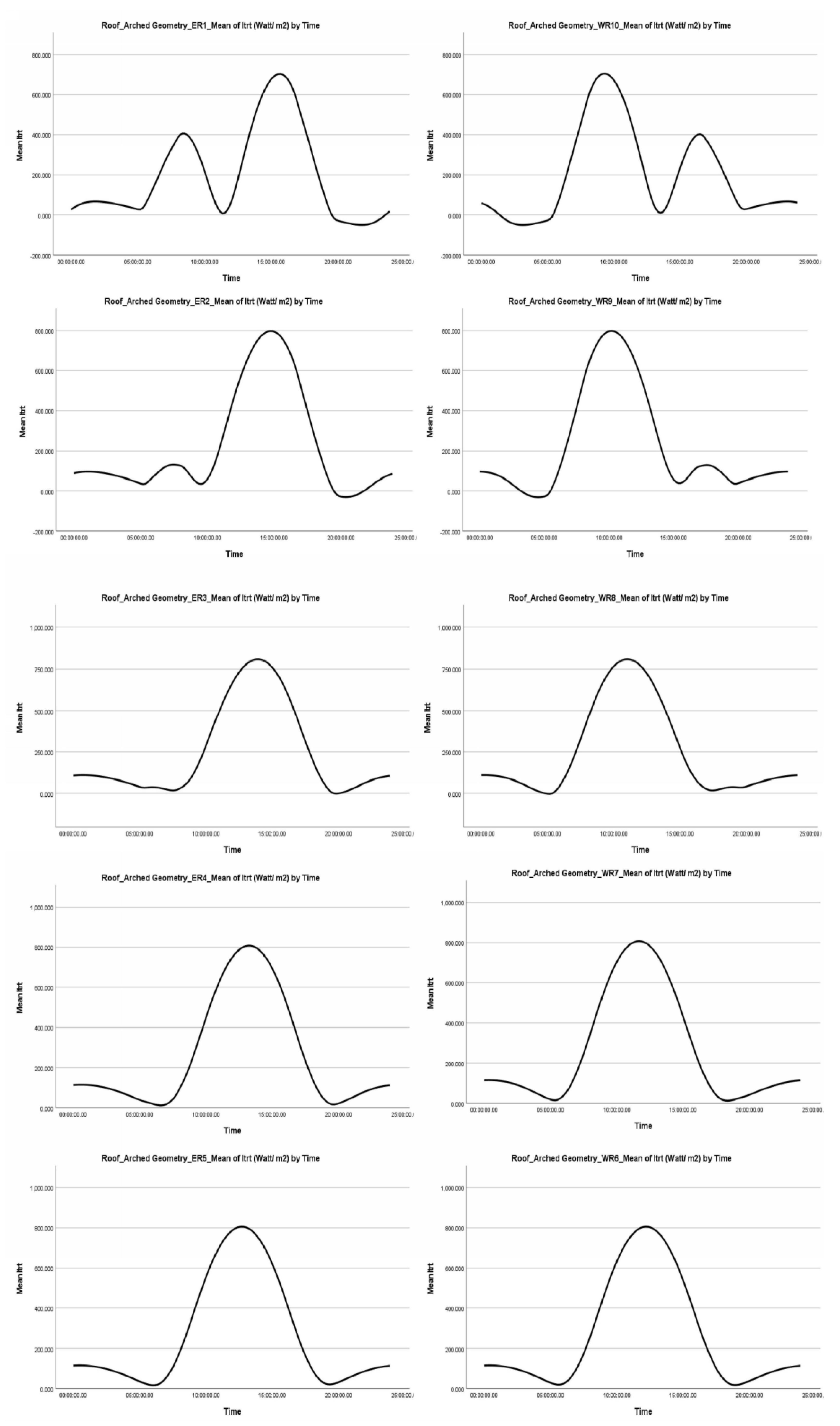

- The vertical side surfaces of the greenhouse (EW, NW, SW, WW) exhibit common results for these two types of radiation across various greenhouse geometries. This consistency arises because these radiations are independent of the covering material, while still sharing common characteristics in terms of orientation and geometry. However, this is not the case for the roof surfaces, which vary due to their distinct geometrical designs. Therefore, the roof surfaces of the greenhouse will be analysed separately for the Even Span and Modified Arched greenhouse configurations

- The roofs of various geometries are symmetrical

- Each roof, regardless of its geometry, consists of surfaces made from the same covering material. For instance, both the east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof geometry are constructed from the same type of glass, while the east and west-facing surfaces of the Modified Arched roof geometry are made of polyethylene

- The average value of total radiation on an inclined surface ( is significantly influenced by the average value of direct radiation on an inclined surface (, which is typically higher than that of diffuse radiation on an inclined surface (. Similarly, for reflected radiation

- The diffuse radiation values on an inclined surface ( can be negative when the surface experiences a shaded sky with very low brightness or when it faces a brightly lit area of the sky near the horizon. This situation occurs when the viewing angle of the surface is directed toward vast regions of the sky with minimal diffuse radiation or during conditions of uneven brightness caused by cloud cover [67,68]

- The radiation reflected from the ground ( always presents positive values, as all surfaces are favoured by this type of radiation when sunlight is available

- The average value of direct and diffuse reflected radiation on an inclined surface is consistent with the average value of direct and diffuse radiation on that surface

- The average values of direct and diffuse reflected radiation align with the average values of direct and diffuse radiation on an inclined surface. This relationship is also consistent for the vertical surfaces corresponding to the same orientation. For the east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof geometry, the average values of reflected radiation in terms of direct and diffuse radiation are consistent. The same holds true for the average value of ground-reflected radiation (

- When the angle of incidence . Therefore, any radiations calculated using the cosine of the specific angle may yield negative values in cases where , such as:

- ✓

- Equation (17) states , indicating that radiation hits the backside of the surface rather than directly illuminating it

- ✓

- Equation (21), the which means that can yield negative values when the sun does not illuminate the area directly in front of the surface, or when the geometry prevents the reflected radiation from reaching the surface

- Furthermore, Equation (21) shows that when either or . Practically:

- ✓

- According to Equation (8) , which means that . In this scenario, the zenith angle , meaning that the angle of elevation of the sun , and indicates that the sun is below the horizon

- ✓

- In conclusion, when the solar angle is small, resulting in a large zenith angle ( and or when the angle of incidence is leading to

- According to Duffie & Beckman [42], negative values of direct radiation on inclined surfaces can mathematically occur when the angle of incidence exceeds 90°. Since these values do not correspond to physically observable phenomena, the common practice in the literature is to treat them as zero. However, in this study, the decision is made to not disregard these values and instead investigate them further to assess their contribution to the computational results. This approach differentiates our methodology and adds an element of innovation to the study. The same consideration applies to reflected radiation. It is important to note that the negative values resulting from the mathematical model indicate heat outflow, which signifies the cooling of the space.

- Skewness measures the distribution of values in relation to the mean and is similar for both vertical surfaces of the greenhouse. The interpretations of skewness are as follows:

- ✓

- Skewness = 0 indicates a symmetric, normal distribution

- ✓

- Skewness > 0 indicates a positive skewness, characterised by many small values and few large values

- ✓

- Skewness < 0 indicates a negative skewness, characterized by many large values and few small values

- Kurtosis measures how extreme values are distributed and is also similar for both vertical surfaces of the greenhouse. The interpretations of kurtosis are as follows:

- ✓

- Kurtosis = 0 indicates a normal distribution (serving as a measure of comparison)

- ✓

- Kurtosis > 0 indicates the presence of many outliers

- ✓

- Kurtosis < 0 indicates the presence of fewer outliers

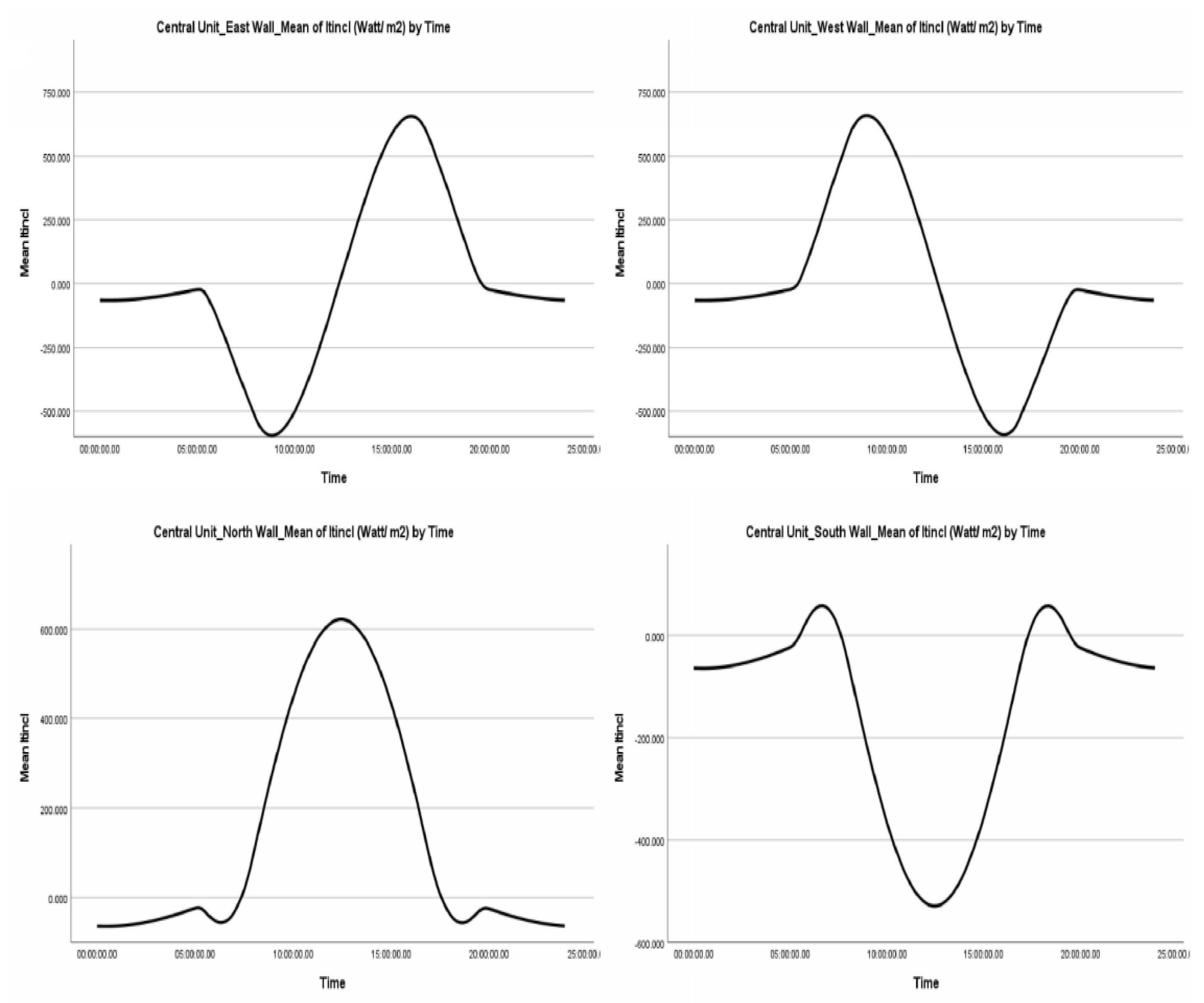

4.2.1. Vertical Greenhouse Surfaces with Even Span and Modified Arched Geometry

- When the average value of radiation on an inclined surface from sunrise to sunset is similar, this is primarily due to the sun’s movement from east to west. This observation holds for surfaces oriented towards the east and west. A similar phenomenon is observed in the reflected radiation between the vertical surfaces oriented to the east and west and those oriented to the north and south

- When the average value of direct radiation on a tilted surface ( is almost exactly symmetrical and inverse, it confirms that the two surfaces receive the same amount of direct radiation, albeit at opposite times of the day or year. This is valid for surfaces-oriented north and south

- The negative values that appear in the case of direct radiation on a tilted surface ( are since during the period when the sun is in the east, the western vertical surface of the greenhouse does not receive any direct radiation. The same principle applies in the opposite scenario. Additionally, the presence of a negative value for direct reflected radiation ( indicates that, based on the orientation of the surface (whether east, west, north, or south), the vertical geometry of the surfaces prevents direct exposure to sunlight. Consequently, when the value of direct radiation on an inclined surface is negative, the corresponding value of direct reflected radiation is also negative

- When the maximum and minimum values of direct radiation on an inclined surface ( show almost the same values between the two vertical surfaces, it underscores the dependence of direct radiation on solar movement. This applies to surface-oriented east and west

- Direct radiation on an inclined surface ( exhibits higher values on the vertical surface oriented to the north compared to that oriented to the south. The essential data is collected from these observations:

- ✓

- Both surfaces have the same slope, which means they are perpendicular to each other with an angle of

- ✓

- The average value of diffuse radiation is identical for both surfaces

- ✓

- There is no shading from the southern surface

- ✓

- The orientation is correctly set, with the northern surface at and the southern surface at

- ✓

- Only the radiation from sunrise to sunset has been considered for each month separately

- ✓

- The direct radiation on an inclined surface ( takes the angle of incidence into account. This means that a smaller angle of incidence results in a higher cosine of the angle , and consequently a higher

- ✓

- Negative values are preserved in both the radiation and cosθ calculations, indicating that the sun is facing the opposite side

- ✓

- Absolute values are not used for which is why negative results appear in the calculations

- Therefore, although the appearance of higher direct radiation values on an inclined surface on the vertical surface with a north orientation compared to that with a south orientation is not expected, it could be justified (taking into account the data already presented):

- ✓

- The smaller angle of incidence results in a higher , which in turn increases . However, there are specific times, such as early morning and late afternoon during spring and autumn, when the sun’s azimuth creates more favorable angles with the vertical north-facing sides. Meanwhile, vertical south-facing surfaces receive more direct radiation on inclined surfaces when is smaller, indicating a larger angle of incidence. For instance, on 21 October, the northeast sunrise benefits the north-facing surface significantly more than the south-facing surface

- ✓

- The latitude of the study area is linked to a particularly low solar path during the winter months, causing the vertical surfaces-oriented east, south, and north to receive solar radiation indirectly or through reflections from the environment, even at low angles

- ✓

- The northern vertical surface tends to receive more radiation during the early morning and late afternoon

- ✓

- However, around midday, when the sun is high in the south, the south-facing surface is favoured. Yet, during the hours near sunrise and sunset, the north-facing surface performs better due to a more optimal angle of incidence between the sun and the vertical surface

- ✓

- Additionally, the transparent covering material allows solar radiation to enter through surfaces of any orientation. This means that the south-facing vertical surface not only permits solar radiation to pass through but also allows it to reflect onto the north-facing surface

- However, for a more precise justification of the higher values presented by direct radiation on a tilted surface However, for a more precise justification of the higher values presented by direct radiation on an inclined surface ( on the vertical surface of the north and south orientation, a statistical analysis was performed, the results of which showed that:

- ✓

- The average incidence angle in the northern hemisphere is . The minimum incidence angle is . These results indicate the presence of direct radiation

- ✓

- The average incidence angle in the southern hemisphere is , leading to , while the minimum angle is , resulting in . This data shows a lack of direct radiation and only minimal instances of positive radiation

- ✓

- Therefore, the larger average value for the northern-facing surfaces is not a calculation error; rather, it is a consequence of the geometric relationship between the sun’s position and the orientation of the wall, particularly during the early morning and late afternoon hours

- In general, the radiation levels on an inclined surface for all four vertical surfaces of the greenhouse exhibit a symmetrical normal distribution. The diffuse radiation on an inclined surface ( shows slightly higher values for all four surfaces, while the direct radiation on an inclined surface ( shows increased values for the east and west-oriented surfaces. The reflected radiation displays a similar pattern on surfaces with corresponding orientations

- Kurtosis across all four orientations, as well as for all types of radiation, indicates a lack of extreme values

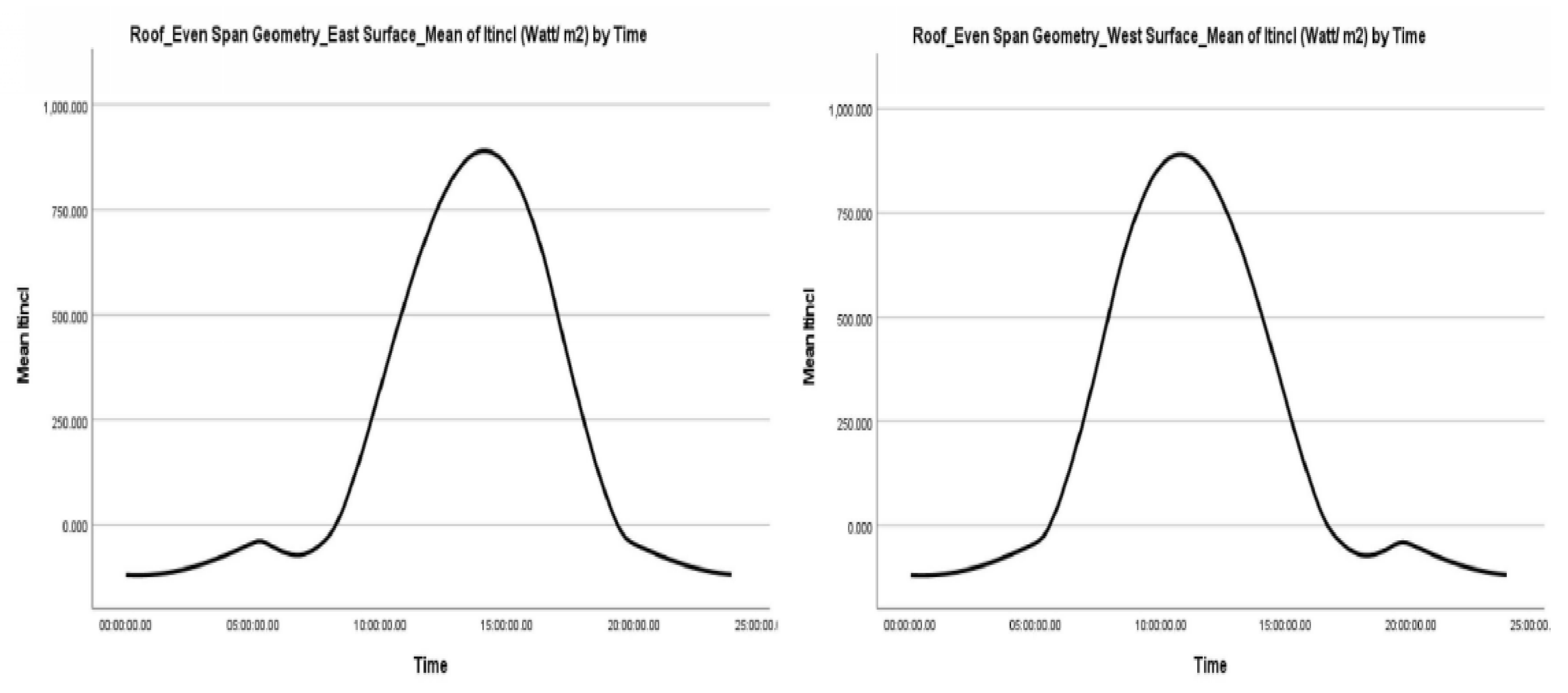

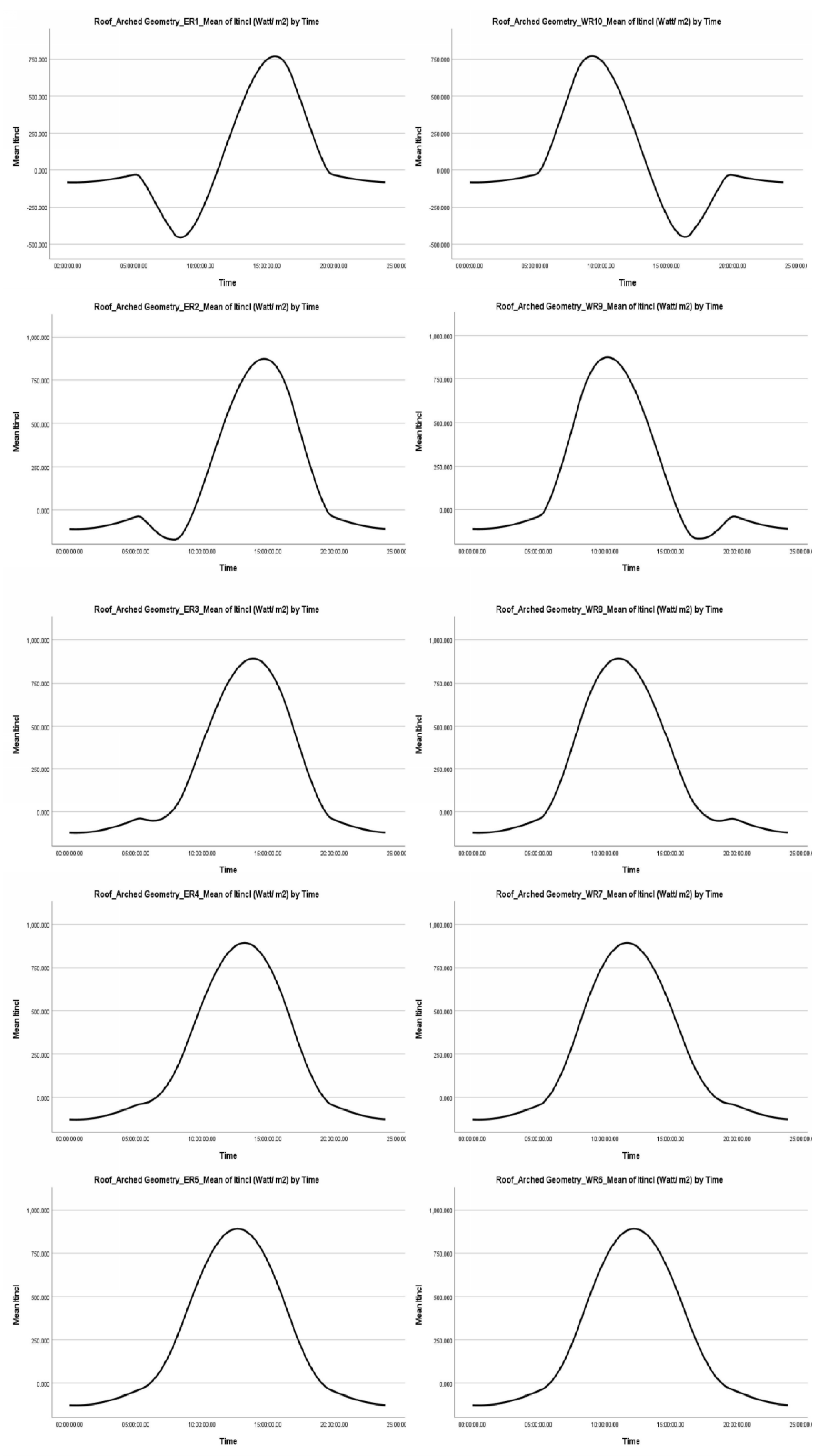

4.2.2. Even Span and Modified Arched Greenhouse Roof Surfaces

- The east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof receive similar average values of direct, indirect, and total radiation, as well as radiation on an inclined surface that is reflected, transmitted, and absorbed by the material. The differences are infinitesimal for the duration of the study and throughout the day, from sunrise to sunset, varying slightly depending on the month. Similarly, the corresponding surfaces of the Modified Arched roof geometry (ER1-WR10, ER2-WR9, ER3-WR8, ER4-WR7, ER5-WR6) show comparable results

- This is primarily due to the symmetrical design of the roof, where the east and west-facing surfaces are geometrically identical, sharing the same inclination angle, surface area, and material. The sun’s path, as it moves from east to west, plays a crucial role; however, the average values remain unchanged due to this symmetry. It’s important to note that this is a roof, not a vertical surface

- On the roof, sunlight exposure is symmetrically equivalent, with morning sunlight hitting the eastern surface and afternoon light illuminating the western surface. This symmetry results in an equivalent solar energy load for both surfaces around noon. Therefore, on average, the surfaces receive an equivalent solar energy load

- Direct radiation on an inclined surface ( shows negative values on the east-facing roof surface during the morning hours and on the west-facing roof surface after noon. Justification:

- ✓

- The large angle of incidence results in negative values for and . However, this does not imply negative solar energy or the absence of solar radiation. Instead, it indicates that the specific surface is oriented away from the sun at that time

- ✓

- In the early morning hours, the sun’s low trajectory justifies the negative values on east-facing roof surfaces. Similarly, as the sun approaches the west during the late afternoon, the low angle also accounts for the negative values on west-facing roof surfaces. To summarise, the sun is positioned lower than the angle of the inclined roof surface

- The diffuse radiation on an inclined surface ( presents values with a negative sign only in the case of the Modified Arched roof geometry. Justification:

- ✓

- The issues mainly arise from negative minimum values of the solar angle

- ✓

- The structure’s complex geometry contributes to these problems, as the roof is composed of multiple narrow and inclined sections that create curvature between them

- ✓

- During the early morning or near sunset, the overlapping geometry of these roof sections causes shading between the surfaces

- ✓

- The limited sky view factor from these surfaces is crucial for receiving diffuse radiation

- The presence of direct reflected radiation ( values with a negative sign is justified by:

- ✓

- In the early morning hours, when the sun is low on the horizon, direct reflected radiation often does not reach the ground in front of greenhouse roof surfaces that are oriented eastward. This is due to shading caused by the geometry of the greenhouse itself

- ✓

- Similarly, during the hours near sunset, direct reflected radiation often fails to reach the ground in front of greenhouse roof surfaces-oriented westward, again due to shading by the greenhouse’s geometry

- ✓

- In these cases, the ground does not serve as an active reflecting surface for direct radiation. As a result, the calculations yield a numerical value with a negative sign to indicate this phenomenon

- ✓

- It is important to note that this negative value does not represent a physical quantity; instead, it serves as a computational indication of the absence of radiative contribution due to geometric incompatibilities in the orientation and exposure of the surfaces

- In general, the radiation symmetry on the inclined east and west roof surfaces of the greenhouse yields identical values. The greenhouse roof exhibits a symmetrical normal distribution. Both the diffuse radiation on the inclined surface ( and the diffuse reflected radiation ( show a similar symmetrical distribution, with a tendency for higher values to appear more frequently than lower values

- The kurtosis displays the same values for both the east and west-facing surfaces. In all scenarios concerning the specific types of radiation, the greenhouse roof demonstrates a lack of extreme values

4.3. Radiations Related to the Technical Characteristics of the Covering Material (Supplementary Materials S3, Tables S10 and S11)

- The transmitted radiation and absorbed radiation by the material (direct, diffuse, and total radiation)

- The average values for direct, diffuse, and total transmitted radiation are comparable for the vertical side surfaces of the greenhouse (EW, NW, SW, WW) across the two different geometries. This observation can be attributed to the uniform geometry of the central unit, the vertical slope of the surfaces, and the transparent covering material. However, this trend does not hold for the roof surfaces, as their geometry and slope differ

- Despite the slight difference in refractive indices between glass and polyethylene , the results are unlikely to vary significantly

- The roofs of different geometries are both symmetrical

- Each roof comprises surfaces made from the same covering material. For instance, the east and west-facing surfaces of the Even Span roof are both constructed from glass, while those of the Modified Arched roof geometry are made of polyethylene

- The direct transmitted radiation ( in all cases does not display negative values

- The diffuse transmitted radiation ( presents negative values across all surfaces in both geometries. This requires further justification:

- ✓

- The calculation depends on the incident diffuse radiation on the external surface

- ✓

- According to Formula (34), ( is the transmissivity) and

- ✓

- According to Formula (32), . The perpendicular and parallel components are positive values, but when their values exceed unity, the transmissivity becomes negative. This means that at extreme angles of incidence, the ratios and may differ numerically

- ✓

- From Formulas (30) and (31), it is evident that the parallel and perpendicular components depend on both the angle of incidence and the angle of refraction, and these components are always positive

- ✓

- It should be noted that the angle of refraction is always constrained within the limits . However, there are instances when

- ✓

- During early morning hours or under conditions of very low total radiation, the incoming diffuse radiation may be minimal or even zero on certain surfaces

- ✓

- In such cases, if the numerical value of the transmitted energy falls below the theoretical minimum limit, the recorded value may turn negative

- The absorbed radiation (direct, diffuse, and total) either does not exhibit negative values or shows values that are extremely close to zero, making them nearly imperceptible

- Negative average values of total absorbed radiation are observed only in cases where average values of total transmitted radiation also exhibit negative values

- The absorptivity of polyethylene coating material is lower than that of glass

- Generally, the radiation symmetry on an inclined surface of the central unit’s vertical surfaces, as well as on the Even Span and modified roof geometry of the greenhouse, displays a symmetrical normal distribution for both transmitted and absorbed radiation (direct, diffuse, and total) with values extremely close to zero (either negative or positive) and without obvious deviations

- The kurtosis shows identical values for the corresponding surfaces and specific radiations, indicating a lack of extreme values

- The average value of transmitted radiation (direct, diffuse, and total) shows similar levels on the vertical side surfaces (EW, NW, SW, WW) for both geometries. This similarity is due to the consistent slope of the surfaces, the symmetrical geometry of the central unit, and the use of transparent materials. In contrast, differences are observed on the roof surfaces, which arise from the varying slopes and geometries of the Even Span and Modified Arched structures.

- Although polyethylene and glass have very close refractive index values ( for polyethylene and for glass), the different geometries can influence the final calculations of transmitted energy. Specifically, the direct transmitted radiation yields only positive values, while the diffuse transmitted radiation exhibits negative values across all surfaces for both geometries.

- The transmittance is calculated from Equation (32), which incorporates ratios that depend on the parallel and perpendicular components of reflectivity. When these ratios deviate, particularly at large angles of incidence , the value of can become negative, resulting in negative radiation values. This occurrence is numerical and relates either to extreme geometric conditions or to low intensity of incoming radiation (such as early morning or late afternoon).

- The absorbed radiation, both diffuse and total, does not present significant negative values, aside from negligible instances where transmitted radiation is also recorded as negative. This is because absorbed radiation is calculated as the difference between incident and transmitted radiation.

- Notably, polyethylene has a lower absorptivity than glass, which is reflected in the reduced absorbed radiation values on the surfaces of the Modified Arched geometry.

5. Conclusions

- Integrates all types of radiation within the greenhouse environment

- Accounts for the geometry and orientation of each surface (both vertical and inclined) across different greenhouse designs, such as Even Span and Modified Arched

- Incorporates material-specific optical properties, such as the refractive index and attenuation coefficient, which allow for a precise assessment of covering materials

- Utilises accurately calculated solar angles based on specific geographical coordinates (latitude, longitude, altitude) and timestamps, ensuring an exact representation of seasonal and daily variations

- Facilitates a detailed analysis of direct, diffuse, and reflected radiation on each surface. This includes scenarios where negative values may occur due to geometric and solar angles, and it preserves these values rather than resetting them to zero. This approach results in a more physically consistent energy balance.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Solar angles | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| ω | Solar Hour Angle (Hour Angle) | ° |

| δ | Declination | ° |

| θ | Angle of incidence of solar radiation | ° |

| h | Angle of solar altitude | ° |

| θz | Zenith angle | ° |

| θr | Angle of refraction | ° |

| γ | Azimuth | ° |

| β | Angle of inclination | ° |

| φ | Latitude | ° |

| Solar Angle Magnitudes | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| ST | Local Solar Time | ° |

| LST | Standard Local Time Dimensionless Number | DN |

| LST | Standard Meridian | ° |

| LI | Local Meridian | ° |

| Et | Time correction function | DN |

| c | Time correction due to change from winter to summer period | DN |

| B | Auxiliary angle | ° |

| n | On the nth calendar day of the year | DN |

| Z | Refractive index Dimensionless Number | DN |

| Radiations | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| Iex | Extra-atmospheric radiation (Atmospheric boundary radiation) | W/m2 |

| Io | Global solar radiation | W/m2 |

| GSC | Solar Constant | W/m2 |

| Ib,incl | Direct radiation reaching the inclined outer surface | W/m2 |

| Id,incl | Diffuse solar radiation reaching the inclined outer surface | W/m2 |

| It,incl | Total solar radiation reaching the inclined outer surface | W/m2 |

| Ib,hor | Direct solar radiation reaching the horizontal outer surface | W/m2 |

| Id,hor | Diffuse solar radiation reaching the horizontal outer surface | W/m2 |

| It,hor | Total solar radiation reaching the horizontal outer surface | W/m2 |

| Ir | Ground reflected radiation on the inclined surface | W/m2 |

| Irb | Reflected diffuse radiation on the inclined surface | W/m2 |

| Ird | Reflected diffuse radiation on the inclined surface | W/m2 |

| Iref | Total reflected radiation incident on the inclined surface | W/m2 |

| Itr b | Transmitted direct radiation | W/m2 |

| Itr d | Transmitted diffuse radiation | W/m2 |

| Itr t | Total transmitted radiation | W/m2 |

| Iabsb | Absorbed direct radiation | W/m2 |

| Iabsd | Absorbed diffuse radiation | W/m2 |

| Iabst | Total absorbed radiation | W/m2 |

| Transmittances | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| τ | Transmittance coefficient (percentage of radiation passing through the surface) | DN |

| Absorptivities | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| αb | Average absorption coefficient of the material | DN |

| τa | Absorption coefficient along the path | DN |

| Coefficients | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| Tb | Direct radiation transmittance of the atmosphere (Direct radiation atmospheric transparency coefficient) | DN |

| Td | Diffuse radiation atmospheric transparency coefficient | DN |

| Mh | Altitude-adjusted air mass | DN |

| m | Air mass (The mass of the atmosphere, which corresponds to the distance that sunlight travels from the atmosphere) | DN |

| Slope Factors | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| Rr | The slope factor of reflected ground radiation | DN |

| Rb | The slope factor of reflected direct radiation | DN |

| Rd | The slope factor of reflected diffuse radiation | DN |

| Components | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| Parallel reflection component | DN | |

| Vertical reflection component | DN | |

| Parallel radiation absorption component | DN | |

| Vertical radiation absorption component | DN | |

| Other quantities | ||

| Symbol | Explanation | Unit |

| a | Altitude | km |

| p | Albedo | DN |

| DN | Dimensionless Number | |

References

- Esen, M.; Yuksel, T. Experimental evaluation of using various renewable energy sources for heating a greenhouse. Energy Build. 2013, 65, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vox, G.; Teitel, M.; Pardossi, A.; Minuto, A.; Tinivella, F.; Schettini, E. Sustainable Greenhouse Systems; Chapter 1; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Baudoin, W.; Nersisyan, A.; Shamilov, A.; Hodder, A.; Gutierrez, D.; Nicola, S.; Chairperson, V.; Duffy, R. Good Agricultural Practices for Greenhouse Vegetable Production in the South East European Countries. In Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Plant Production and Protection Division Principles for Sustainable Intensification of Smallholder Farms; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-92-5-109622-2. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, B.; Vandorou, F.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Vaiopoulos, K.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G. Energy Use in Greenhouses in the EU: A Review Recommending Energy Efficiency Measures and Renewable Energy Sources Adoption. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righini, I.; Vanthoor, B.; Verheul, J.M.; Naseer, M.; Maessen, H.; Persson, T.; Stanghellini, C. A greenhouse climate-yield model focussing on additional light, heat harvesting and its validation. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 194, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choab, N.; Allouhi, A.; El Maakoul, A.; Kousksou, T.; Saadeddine, S.; Jamil, A. Review on greenhouse microclimate and application: Design parameters, thermal modeling and simulation, climate controlling technologies. Sol. Energy 2019, 191, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemali, K. History of Controlled Environment Horticulture: Greenhouses. HortScience 2022, 57, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.J.; Chandra, P. Effect of greenhouse design parameters on conservation of energy for greenhouse environmental control. Energy 2002, 27, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beithou, N.; Qandil, A.; Khalid, M.B.; Horvatinec, J.; Ondrasek, G. Review of Agricultural-Related Water Security in Water-Scarce Countries: Jordan Case Study. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.; Farhangi, S.; van de Vlasakker, P.C.H.; Carsjens, G.J. The Role of Urban Agriculture Technologies in Transformation toward Participatory Local Urban Planning in Rafsanjan. Land 2021, 10, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elsner, B.; Briassoulis, D.; Waaijenberg, D.; Mistriotis, A.; Von Zabeltitz, C.; Gratraud, J.; Russo, G.; Suay-Cortes, R. Review of structural and functional characteristics of greenhouses in European union countries: Part I, design requirements. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 2000, 75, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Henten, E.J.; Bakker, J.C.; Marcelis, L.F.M.; van’t Ooster, A.; Dekker, E.; Stanghellini, C.; Vanthoor, B.; Van Randeraat, B.; Westra, J. The adaptive greenhouse-an integrated system approach to developing protected cultivation system. Acta Hortic. 2006, 718, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heurn, E.; Van der Post, K. Protected Cultivation: Construction, Requirements and Use of Greenhouses in Various Climates; Agrodok (Vol. 23); Agromisa Foundation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004; CTA Publications; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/73088 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Dougka, G.; Briassoulis, D. Load carrying capacity of greenhouse covering films under wind action: Optimising the supporting systems of greenhouse films. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 192, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Rhee, J.Y. Utilization and performance evaluation of a surplus air heat pump system for greenhouse cooling and heating. Appl. Energy 2013, 105, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Henten, E. Greenhouse Climate Management: An Optimal Control Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1994. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/greenhouse-climate-management-an-optimal-control-approach-1vlmgknssx.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Fox, J.A.; Adriaanse, P.; Stacey, N.T. Greenhouse energy management: The thermal interaction of greenhouses with the ground. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wei, R.; Xu, L. Energy Consumption Prediction of a Greenhouse and Optimization of Daily Average Temperature. Energies 2018, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanthoor, B.H.E.; Stanghellini, C.; van Henten, E.J.; de Visser, P.H.B. A methodology for model-based greenhouse design: Part 1, a greenhouse climate model for a broad range of designs and climates. Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 110, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanthoor, B.H.E.; de Visser, P.H.B.; Stanghellini, C.; van Henten, E.J. A methodology for model-based greenhouse design: Part 2, description and validation of a tomato yield model. Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 110, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, L.; Xia, X. Hierarchical model predictive control of Venlo-type greenhouse climate for improving energy efficiency and reducing operating cost. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modest, M.F. Radiative Heat Transfer, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/915945267/Radiative-Heat-Transfer-Third-Edition-Michael-F-Modest-available-instanly (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Law Number 2243/333582, Sheet Number 5432. 9 December 2020. Available online: http://www.minagric.gr/images/stories/docs/agrotis/KANABH/fe5432_091220_ya333582.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Taki, M.; Rohani, A.; Rahmati-Joneidabad, M. Solar thermal simulation and applications in greenhouse. Inf. Process. Agric. 2017, 5, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, F.; Heeren, N.; Hellweg, S.; Roshandel, R. Optimisation of energy-efficient greenhouses based on an integrated energy demand-yield production model. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 202, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, E.; Hemming, S.; Stanghellini, C. Materials with switchable radiometric properties: Could they become the perfect greenhouse cover? Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 193, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafaras, I.; Campen, J.B.; Stanghellini, C.; de Zwart, H.F.; Voogt, W.; Scheffers, K.; Al Harbi, A.; Al Assaf, K. Intelligent greenhouse design decreases water use for evaporative cooling in arid regions. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piché, P.; Haillot, D.; Gibout, S.; Arrabie, C.; Lamontagne, M.A.; Gilbert, V.; Bédécarrats, J.P. Design, construction and analysis of a thermal energy storage system adapted to greenhouse cultivation in isolated northern communities. Sol. Energy 2020, 204, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulard, T.; Baille, A. Analysis of thermal performance of a greenhouse as a solar collector. Energy Agric. 1987, 6, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Primary Industry. Greenhouse Covering Material. Available online: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/horticulture/greenhouse/structures-and-technology/covers (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Munoz-Liesa, J.; Cuerva, E.; Parada, F.; Volk, D.; Gass´o-Domingo, S.; Josa, A.; Nemecek, T. Urban greenhouse covering materials: Assessing environmental impacts and crop yields effects. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, D.; Baglivo, C.; Panico, S.; Congedo, M.P. Solar greenhouses: Climates, glass selection, and plant well-being. Sol. Energy 2021, 230, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Environmental sustainability of greenhouse covering materials. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoy, N.; Prado, V.; Wypkema, A.; Quist, J.; Mourad, M. Anticipatory Life Cycle Assessment of sol-gel derived anti-reflective coating for greenhouse glass. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 221, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greek Cadastral. Available online: http://gis.ktimanet.gr/wms/ktbasemap/default.aspx (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Baglivo, C.; Mazzeo, D.; Panico, S.; Bonuso, S.; Matera, N.; Congedo, P.M.; Oliveti, G. Complete greenhouse dynamic simulation tool to assess the crop thermal well-being and energy needs. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 179, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, F.; Al-Ansari, T. Design and analysis of a renewable energy driven greenhouse integrated with a solar still for arid climates. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 258, 115512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Deng, L.; Li, A.; Gao, R.; Zhang, L.; Lei, W. Analytical model for solar radiation transmitting the curved transparent surface of solar greenhouse. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.A.S.; Hizam, H.; Gomes, C. Estimation of Hourly, Daily and Monthly Global Solar Radiation on Inclined Surfaces: Models Re-Visited. Energies 2017, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-470-87366-3 (cloth); ISBN 978-1-118-41541-2 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118 41812-3 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-43348-5 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-67160-3 (ebk). [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M. An Introduction to Solar Radiation; Academic Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, J.; Kavadias, K.; Zafirakis, D. Experimental validation of the optimum photovoltaic panels’ tilt angle for remote consumers. Renew. Energy 2012, 46, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twidell, J.; Weir, T. Renewable Energy Resources, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 9780203478721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.A. Calculation of Monthly Average Insolation on Tilted Surfaces. Sol. Energy 1977, 19, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ma, Y.; Pang, Z. A mathematical model of global solar radiation to select the optimal shape and orientation of the greenhouses in southern China. Sol. Energy 2020, 205, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E. Optics, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017; pp. 108–109. Available online: https://studylib.net/doc/26323708/optics-fifth-edition-global-edition (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Kozai, T.; Goudriaan, J.; Kimura, M. Light Transmission and Photosynthesis in Greenhouses; Wageningen Centre for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1978; Available online: https://researchgate.net (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Smith, R.D.; Loewenstein, V.E. Optical constants of far infrared materials. 3: Plastics. Appl. Opt. 1975, 14, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreith, F.; Kreider, J.F. Principles of Solar Engineering; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y.; Jordan, R.C. The interrelationship and characteristic distribution of direct, diffuse and total solar radiation. Sol. Energy 1960, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psiloglou, B.E.; Kambezidis, H.D. Performance of the meteorological radiation model during the solar eclipse of 29 March 2006. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 6047–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, J.; Xie, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Li, J.; He, Z.; Wang, C. Solar Radiation Allocation and Spatial Distribution in Chinese Solar Greenhouses: Model Development and Application. Energies 2020, 13, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronoh, E.K. Estimation of Total Solar Radiation Incident on an Inclined Surface of a South-Facing Greenhouse Roof. J. Sustain. Energy 2017, 8, 54–59. Available online: https://oaji.net/articles/2017/3336-1513283214.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- El-Sebaii, A.A.; Al-Hazmi, F.S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Yaghmour, S.J. Global, direct and diffuse solar radiation on horizontal and tilted surfaces in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, B. Ground Albedo Measurements and Modeling; Bifacial PV Workshop: Lakewood, CO, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy20osti/72589.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Gueymard, C.A. Direct and indirect uncertainties in the prediction of tilted irradiance for solar engineering applications. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Solar Energy Engineering: Processes and Systems, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hottel, H.C. A simple model for estimating the transmittance of direct solar radiation through clear atmospheres. Sol. Energy 1976, 19, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ding, X.; Li, T.; Pu, W.; Lou, W.; Hou, J. Dynamic energy balance model of a glass greenhouse: An experimental validation and solar energy analysis. Energy 2020, 198, 117281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, V.P. On the selection of shape and orientation of a greenhouse: Thermal modeling and experimental validation. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrukh Anis, M.; Jamil, B.; Azeem Ansari, M.; Bellos, E. Generalized Models for Estimation of Global Solar Radiation Based on Sunshine Duration and Detailed Comparison with the Existing: A Case Study for India. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 31, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirci, K. Models of Solar Radiation with Hours of Bright Sunshine: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2580–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambezidis, H.D. The Sky-Status Climatology of Greece: Emphasis on Sunshine Duration and Atmospheric Scattering. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambezidis, H.D.D.; Psiloglou, B.E.E.; Gueymard, C. Measurements and Models for Total Solar Irradiance on Inclined Surface in Athens, Greece. Sol. Energy 1994, 53, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badescu, V. 3D Isotropic Approximation for Solar Diffuse Irradiance on Tilted Surfaces. Renew. Energy 2022, 26, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratyev, K.J.; Manolova, M.P. The radiation balance of slopes. Sol. Energy 1960, 4, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazotos, P.; Vasileiou, E.; Vasilakis, S.; Perraki, M. A novel hydrogeochemical approach to delineate the origin of potentially toxic elements in groundwater: Sophisticated molar ratios as environmental tracers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 74771–74790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazotos, P.; Vasileiou, E.; Perraki, M. The synergistic role of agricultural activities in groundwater quality in ultramafic environments: The case of the Psachna basin, central Euboea, Greece. Environ. Monit Assess 2019, 191, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remoundaki, E.; Vasileiou, E.; Philippou, A.; Perraki, M.; Kousi, P.; Hatzikioseyian, A.; Stamatis, G. Groundwater Deterioration: The Simultaneous Effects of Intense Agricultural Activity and Heavy Metals in Soil. Procedia Eng. 2016, 162, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulia, J.; Makris, J.; Drakopoulou, V. Local seismic array observations at north Evoikos, central Greece, delineate crustal deformation between the North Aegean Trough and Corinthiakos Rift. Tectonophysics 2006, 423, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetatos, C.; Kiratzi, A.; Kementzetzidou, K.; Roumelioti, Z.; Karakaisis, G.; Scordilis, E.; Latoussakis, I.; Drakatos, G. The Psachna (Evia Island) Earthquake Swarm of June 2003. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2004, 36, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, J.; Papoulia, J.; Drakatos, G. Tectonic deformation and microseismicity of the Saronikos Gulf, Greece. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2004, 94, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkani, A.; Evelpidou, N.; Tzouxanioti, M.; Petropoulos, A.; Santangelo, N.; Maroukian, H.; Spyrou, E.; Lakidi, L. Flash Flood Susceptibility Evaluation in Human-Affected Areas Using Geomorphological Methods—The Case of 9 August 2020, Euboea, Greece. A GIS-Based Approach. GeoHazards 2021, 2, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulos, A.; Ktena, A.; Manasis, C.; Voliotis, S. Impact of a Periodic Power Source on a RES Microgrid. Energies 2019, 12, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Kravvaritis, E.; Stavlas, D.G.; Stamatopoulos, V.; Gonidis, A.; Koukou, M.K. Investigating the performance of a test phase change material chamber for passive solar applications: Experimental and theoretical approach. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2015, 34, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthimiou, V.D.; Katsanos, C.O.; Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Filios, A.E.; Koukou, M.K.; Layrenti, F.G. Experimental measurements and theoretical predictions of flowfield and temperature distribution inside a wall solar chimney. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2007, 221, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrachopoulos, M.G.; Stavlas, D.G.; Kravvaritis, L.D.; Koukou, M.K.; Vlachakis, N.W.; Orfanoudakis, N.G.; Mavromatis, S.A.; Gonidis, A.G. Performance Testing Of Reflective Insulation Applied In A Prototype Experimental Chamber In Greece: Experimental Results For Summer And Winter Periods. WIT Trans. Eng. Sci. 2008, 61, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavga, A.; Evangelopoulou, F.; Koulopoulou, C.; Zografou, M.; Lycoskoufis, I. Effects of infrared radiation (IR) on growth parameters of eggplant cultivation and greenhouse energy efficiency. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1296, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavga, A.; Trypanagnostopoulos, G.; Koulopoulos, A.; Tripanagnostopoulos, Y. Implementation of photovoltaics on greenhouses and shading effect to plant growth. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1242, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanou, C.; Fidaros, D.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Yearly numerical evaluation of greenhouse cover materials. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 149, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulas, N.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Online professional irrigation scheduling system for greenhouse crops. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1154, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Sigrimis, N.A. Adaptive irrigation method for closed cultivation in greenhouse. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao/Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2015, 31, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirogiannis, I.L.; Katsoulas, N.; Savvas, D.; Karras, G.; Kittas, C. Relationships between Reflectance and Water Status in a Greenhouse Rocket (Eruca sativa Mill.) Cultivation. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 78, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Maletsika, P.; Siomos, A.; Kittas, C. Effects of a UV-absorbing greenhouse covering film on tomato yield and quality. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 10, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitta, E.; Katsoulas, N.; Savvas, D. Shading Effects on Greenhouse Microclimate and Crop Transpiration in a Cucumber Crop Grown Under Mediterranean Conditions. Am. Soc. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2012, 28, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirogiannis, I.; Savvas, D.; Katsoulas, N.; Kittas, C. Evaluation of crop reflectance indices for greenhouse irrigation scheduling. Acta Hortic. 2012, 927, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntinas, G.K.; Morichovitis, Z.; Nikita-Martzopoulou, C.H. The influence of a hybrid solar energy saving system on the growth and the yield of tomato crop in greenhouses. Acta Hortic. 2012, 952, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntoula, E.; Katsoulas, N.; Kittas, C.; Youssef, A.; Exadaktylos, V.; Berckmans, D. Data based modeling approach for greenhouse air temperature and relative humidity. Acta Hortic. 2012, 952, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavga, A.; Alexopoulos, G.; Panidis, T.H. Experimental investigation of the potential of near infrared heating (NIR) in comparison to forced air heating. Acta Hortic. 2012, 927, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidaros, D.; Baxevanou, C.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Investigation of flow patterns in a greenhouse with mechanically assisted ventilation. Acta Hortic. 2011, 893, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidaros, D.K.; Baxevanou, C.A.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Numerical simulation of thermal behavior of a ventilated arc greenhouse during a solar day. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirogiannis, I.; Katsoulas, N.; Kittas, C. Effect of Irrigation Scheduling on Gerbera Flower Yield and Quality. HortScience Horts 2010, 45, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanou, C.; Fidaros, D.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Numerical simulation of solar radiation, air flow and temperature distribution in a naturally ventilated tunnel greenhouse. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR E-J. 2010, 12, 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kavga, A.; Panidis, T.; Bontozoglou, V.; Pantelakis, S. Infrared heating of greenhouses revisited: An experimental and modeling study. Trans. ASABE 2009, 52, 2055–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peponakis, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Petsani, D.; Kittas, C.; Tchamitchian, M. Development of a simple growth model for light control in tomato seedling production. Acta Hortic. 2009, 807, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanou, C.; Bartzanas, T.; Fidaros, D.; Kittas, C. Solar radiation distribution in a tunnel greenhouse. Acta Hortic. 2008, 801, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavga, A.; Pantelakis, S.; Panidis, T.H.; Bontozoglou, V. Investigation of the potential of long wave radiation heating to reduce energy consumption for greenhouse heating. Acta Hortic. 2008, 801, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaraki, S.I.; Papadakis, G. Simulation of a greenhouse solar heating system with seasonal storage in Greece. Acta Hortic. 2008, 801, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulas, N.; Kittas, C.; Dimokas, G.; Lykas, C. Effect of Irrigation Frequency on Rose Flower Production and Quality. Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 93, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, M.; Tripanagnostopoulos, Y.; Kavga, A. The use of Fresnel lenses to reduce the ventilation needs of greenhouses. Acta Hortic. 2006, 719, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittas, C.; Karamanis, M.; Katsoulas, N. Air temperature regime in a forced ventilated greenhouse with rose crop. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittas, C.; Dimokas, G.; Lykas, C.H.; Katsoulas, N. Effect of two irrigation frequencies on rose flower production and quality. Acta Hortic. 2005, 691, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulas, N.; Baille, A.; Kittas, C. SE—Structures and Environment: Influence of Leaf Area Index on Canopy Energy Partitioning and Greenhouse Cooling Requirements. Biosyst. Eng. 2002, 83, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulas, N.; Baille, A.; Kittas, C. Effect of misting on transpiration and conductances of a greenhouse rose canopy. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 106, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baille, A.; Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N. Influence of whitening on greenhouse microclimate and crop energy partitioning. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 107, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Baille, A. SE—Structures and Environment: Influence of Greenhouse Ventilation Regime on the Microclimate and Energy Partitioning of a Rose Canopy during Summer Conditions. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 2001, 79, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulas, N.; Kittas, C.; Baille, A. Estimating transpiration rate and canopy resistance of a rose crop in a fan-ventilated greenhouse. Acta Hortic. 2001, 548, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Baille, A. Transpiration and energy balance of a greenhouse rose crop in mediterranean summer conditions. Acta Hortic. 2001, 559, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, G.C.; Tsagas, N.F. Technology, thermal analysis and economic evaluation of a sunspace located in northern Greece. Energy Build. 2000, 31, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Baille, A. Influence of misting on the diurnal hysteresis of canopy transpiration rate and conductance in a rose greenhouse. Acta Hortic. 2000, 534, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakoura, V.; Stavrianakou, S.; Liakopoulos, G.; Karabourniotis, G.; Manetas, Y. Effects of UV-B radiation on Olea europaea: Comparisons between a greenhouse and a field experiment. Tree Physiol. 1999, 19, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittas, C.; Katsoulas, N.; Baille, A. Transpiration and canopy resistance of greenhouse soilless roses: Measurements and modeling. Acta Hortic. 1999, 507, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, G.; Manolakos, D.; Kyritsis, S. Solar Radiation Transmissivity of a Single-Span Greenhouse through Measurements on Scale Models. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1998, 71, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloupa, E.; Papadopoulos, A.; Bladenopoulou, S. Evapotranspiration and Preliminary Crop Coefficient of Gerbera Soilless Culture Grown in Plastic Greenhouse. Acta Hortic. 1993, 335, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Sun, Z.; Sigrimis, N.; Li, T. Energy sustainability performance of a sliding cover solar greenhouse: Solar energy capture aspects. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 176, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| X (m) | Y (m) |

|---|---|

| 469,305.831 | 4,268,889.046 |

| 469,372.242 | 4,268,891.162 |

| 469,447.384 | 4,268,751.198 |

| 469,335.994 | 4,268,730.825 |

| Even Span | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW | EW | SW | WW | ER | WR | |

| Length (L) (m) | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Height of Vertical Sides (H) (m) | 3 | |||||

| Height of Roof Ridge (H) (m) | 1.15 | |||||

| Slope (β) (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 30 | 30 |

| Azimuth (γ) (°) | 0 | 90 | 180 | −90 | 90 | −90 |

| Modified Arched | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NW | EW | SW | WW | ER1 | ER2 | ER3 | ER4 | ER5 | WR6 | WR7 | WR8 | WR9 | WR10 | |

| Length (L) (m) | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Height of Vertical Sides (H) (m) | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Height of Roof Ridge (H) (m) | 1.15 | |||||||||||||

| Slope (β) (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 73 | 44 | 25 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 25 | 44 | 73 |

| Azimuth (γ) (°) | 0 | 90 | 180 | −90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | −90 | −90 | −90 | −90 | −90 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Standard Meridian LST | 30° |

| Local Meridian LI | 23°39′00.2″ |

| Latitude φ | 38°34′11.5″ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pomoni, D.I.; Koukou, M.K.; Vrachopoulos, M.G. A Comprehensive Mathematical Model for the Estimation of Solar Radiation and Comparative Analysis in Greenhouses with Two Distinct Geometries and Covering Materials: Case Study in Psachna, Evia, Greece. Eng 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010006

Pomoni DI, Koukou MK, Vrachopoulos MG. A Comprehensive Mathematical Model for the Estimation of Solar Radiation and Comparative Analysis in Greenhouses with Two Distinct Geometries and Covering Materials: Case Study in Psachna, Evia, Greece. Eng. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010006

Chicago/Turabian StylePomoni, Dimitra I., Maria K. Koukou, and Michail Gr. Vrachopoulos. 2026. "A Comprehensive Mathematical Model for the Estimation of Solar Radiation and Comparative Analysis in Greenhouses with Two Distinct Geometries and Covering Materials: Case Study in Psachna, Evia, Greece" Eng 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010006

APA StylePomoni, D. I., Koukou, M. K., & Vrachopoulos, M. G. (2026). A Comprehensive Mathematical Model for the Estimation of Solar Radiation and Comparative Analysis in Greenhouses with Two Distinct Geometries and Covering Materials: Case Study in Psachna, Evia, Greece. Eng, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010006