1. Introduction

Bone metastases are the most common systemic complications of cancer progression [

1], with higher occurrence in the spine due to its abundance of red bone marrow and extensive vascularization [

2]. As a result, the spine becomes the primary site of skeletal metastatic involvement, with approximately 10% of all cancer patients, and up to 40% of individuals with confirmed metastatic bone disease, developing symptomatic spinal metastases [

3,

4]. These lesions most frequently arise from highly prevalent solid tumors, including prostate cancer (85% of cases), breast cancer (70%), and, to a lesser extent, lung and kidney cancers (up to 40%) [

5], whose biological aggressiveness and hematogenous dissemination patterns facilitate colonization of the vertebral bone microenvironment [

6]. The combination of a rich vascular supply and relatively slow blood flow within the medullary spaces creates a permissive niche for circulating tumor cells, promoting their adhesion to the endothelial lining, extravasation, and eventual integration into the endosteal surface [

7].

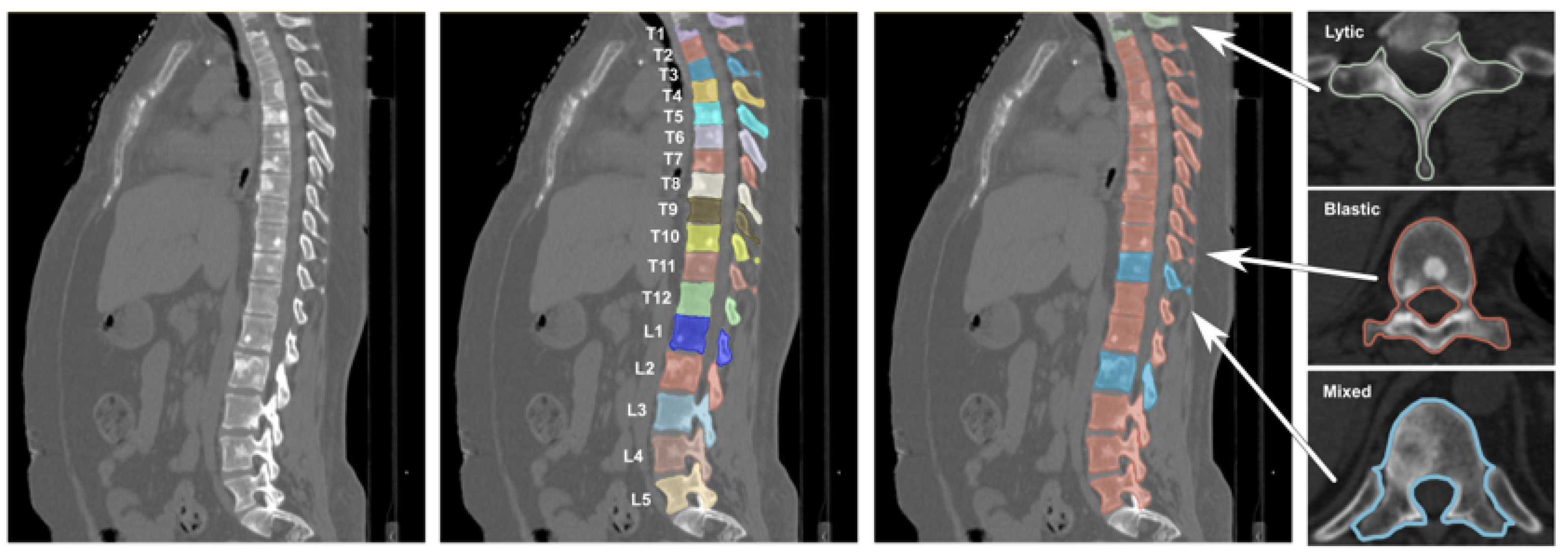

Under physiological conditions, bone homeostasis is tightly regulated by the coordinated interaction of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes; however, the infiltration of malignant cells disrupts this delicate cellular balance, giving rise to abnormal bone remodeling processes that manifest clinically as osteolytic, osteoblastic, or mixed metastatic lesions [

8]. These distinct phenotypes exhibit characteristic radiographic signatures, ranging from focal bone destruction in lytic lesions to aberrant bone formation in blastic lesions, resulting in variable attenuation patterns on computed tomography (CT) imaging [

9], thus posing significant challenges for automated classification models, particularly in datasets where lesion subtypes co-exist and present overlapping or ambiguous imaging characteristics. Moreover, spinal metastases carry a poor prognosis, with survival typically ranging from three to sixteen months, making treatment largely palliative [

10], even though recent improvements in systemic therapies have increased survival and highlighted the need for effective management strategies to preserve neurological function, spinal stability, and overall quality of life [

11,

12].

In this context, early and accurate diagnosis is critical for enabling timely intervention and mitigating the risk of neurological or structural complications, underscoring the central role of diagnostic imaging. Among available modalities, CT is particularly valuable, as it provides high-resolution characterization of bone involvement, allows assessment of spinal stability, and enables differentiation between osteolytic and osteoblastic components [

13]. Moreover, CT is crucial for preoperative planning, especially when instrumentation or stabilization procedures are required, and serves as a reliable alternative for patients in whom magnetic resonance imaging is contraindicated [

14].

In recent years, computer-aided detection (CADe) and diagnosis (CADx) methods powered by artificial intelligence have increasingly been explored as support tools to enhance radiologists’ efficiency and reduce the time and subjectivity associated with manual interpretation [

15]. A variety of computational approaches have been proposed, ranging from classical machine learning (ML) pipelines to modern deep learning (DL) architectures [

16]. For instance, Yao et al. [

17] employed a watershed algorithm to identify candidate lytic lesions and extracted a set of 26 quantitative descriptors, which were subsequently classified using a support vector machine trained on manually expert-annotated segmentations. Similarly, Peter et al. [

18] proposed a Bayesian model combined with a Markov random field to classify metastatic regions based on local intensity differences between pathological and surrounding healthy vertebral tissue, while Hammon et al. [

19] introduced a multi-stage Random Forest framework capable of detecting both lytic and sclerotic thoracolumbar lesions on CT images. More recently, Hong et al. [

20] also adopted a Random Forest classifier to differentiate osteoblastic metastases from benign bone islands, demonstrating the continued relevance of ensemble learning in this domain.

The advent of DL has further expanded the capabilities of CADe and CADx systems for spinal imaging. Roth et al. [

21] explored convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to reduce false positives in vertebral lesion detection by integrating multiple 2D CNN observations. More recent studies like the one from Motohashi et al. [

22] developed a DL algorithm for automated detection of spinal metastases, while Koike et al. [

23] proposed a two-stage framework combining YOLOv5 for vertebral identification and InceptionV3 for binary classification of lytic lesions. Across these efforts, reported accuracies typically range between 81% and 95%, confirming the potential of DL-driven algorithms to support faster and more reliable clinical decision-making. Although these models achieved strong performance, their success was facilitated by the availability of thousands of images and extensive manual labeling, underscoring the dependency of DL approaches on large, diverse, and well-annotated datasets, a requirement that often limits their applicability in real-world clinical settings, where imaging data are heterogeneous, class-imbalanced, and costly to annotate.

Despite these methodological advances, the successful integration of these systems into real-world clinical workflows depends not only on diagnostic accuracy but also on usability, interpretability, and seamless interaction with clinical existing tools [

24,

25]. Several commercial and research platforms, such as OsiriX MD, 3DICOM MD, and SenseCare, already provide advanced DICOM visualization and post-processing capabilities, including 3D rendering and interactive exploration of medical images, and some have obtained regulatory clearance for diagnostic use. However, these systems lack automatic classification functionalities and are not tailored to the needs of spinal oncology, where lesion detection remains particularly complex and time-consuming [

26]. This gap underscores the need for specialized, interpretable, and workflow-compatible end-to-end solutions to assist clinicians in the diagnosis and assessment of spinal metastatic disease.

In this context, the present study introduces a complete and interpretable radiomics-based pipeline for the automatic classification of vertebrae as healthy or metastatic from CT-derived segmentations, coupled with an interactive 3D visualization module implemented in Unity 3D. Starting from pre-existing segmentations, the proposed framework integrates DICOM preprocessing, radiomic feature extraction and selection, informed undersampling to address class imbalance, and automatic Random Forest classification, achieving competitive diagnostic performance while preserving transparency and clinical interpretability. Furthermore, the development of a non-immersive VR desktop application provides an intuitive 3D visualization environment that enables clinicians to explore patient-specific spinal models and compare algorithmic predictions with expert judgment. Together, these contributions offer a practical and extensible foundation for computer-assisted assessment of spinal metastases, filling a gap between high-accuracy computational methods and the usability requirements of real-world clinical practice.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 present the methodology adopted, including the description of the dataset preparation, classification pipeline, and 3D visualization module implementation.

Section 3 reports the experimental results, which are further analyzed and discussed in

Section 4. Finally, conclusions are drawn in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

The overall methodological workflow is summarized in

Figure 1, which outlines all the key stages of the proposed framework, from dataset preparation to radiomic feature extraction, ML-based classification, and final 3D interactive visualization.

The methodological approach is organized into three main components, described as follows:

Section 2.1 describes the construction of the dataset used for model training and testing;

Section 2.2 presents the radiomic-based classification pipeline, including details on feature extraction, normalization, and dimensionality reduction, and the configuration of the ML classifier; and finally,

Section 2.3 describes the visualization module, based on a Virtual Reality (VR) 3D interaction environment.

2.1. Dataset Preparation

This study was conducted using the Spine-METS-CT-SEG dataset, a publicly available collection hosted on The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) [

27]. The dataset comprises 55 anonymized CT examinations of the spine from oncologic patients diagnosed with vertebral metastases. All images were acquired at the Radiation Oncology Department of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA, USA) using Siemens SOMATOM Confidence (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) and GE Lightspeed (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) scanners.

The cohort represents a heterogeneous population of patients with diverse primary tumor origins and varying types of bone metastatic lesions, ensuring broad representativeness of clinical conditions. For each patient, three types of data are provided: (i) a 3D axial CT volume in DICOM format; (ii) a corresponding DICOM-SEG file containing manual segmentations of all visible vertebrae performed by two domain experts with specific expertise in biomechanics and medical image analysis of pathological spines; and (iii) an associated clinical report including information on the primary tumor type, metastasis location, and lesion classification.

Vertebral labeling followed the Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score (SINS) criteria [

28], classifying each vertebra into one of four categories: healthy (no lesion), osteolytic lesion, osteoblastic lesion, or mixed lesion. An example of CT images contained in the Spine-METS-CT-SEG dataset can be seen in

Figure 2.

CT images acquired from patient 17 were excluded from the analysis due to a corrupted segmentation file, which prevented the reconstruction of valid binary masks from the corresponding DICOM-SEG data. A total of 765 vertebrae were analyzed across all subjects. Among these, 597 vertebrae were labeled as healthy, while 168 vertebrae were labeled as metastatic, revealing a substantial class imbalance that motivated the implementation of data balancing strategies, as detailed in the following.

2.1.1. Image Preprocessing

The original DICOM axial CT images and the corresponding 3D vertebral segmentation masks provided within the Spine-METS-CT-SEG dataset were imported into Python (version 3.12.7) and the 3D Slicer (version 5.8.1) environment for subsequent analysis. The segmentation masks encompass the entire vertebral body, including any metastatic lesions contained within, thereby enabling the extraction of quantitative radiomic features representative of the whole vertebra. Each segmentation was reconstructed directly from the DICOM-SEG files included in the dataset, exploiting the spatial metadata stored in each frame, particularly the information referring to the Z-axis position and voxel geometry. The DICOM series of axial CT slices was first converted into 3D volumetric representations using the SimpleITK library (version 2.5.3), which accurately preserves the spatial properties encoded in the DICOM headers (origin, voxel spacing, and image orientation) [

29]. This step ensured the generation of consistent volumetric data for each patient, suitable for further quantitative and visual analyses. For every segmented vertebra, an individual binary 3D mask was reconstructed, assigning a value of 1 to voxels belonging to the segmented structure and 0 to the background. These vertebral masks were then registered and spatially realigned with respect to the geometry of the original CT volume, ensuring exact voxel-to-voxel correspondence between the segmented region and its anatomical location within the patient’s imaging data, guaranteeing geometric fidelity and spatial consistency across all reconstructed volumes, which are essential for reliable radiomic feature extraction and subsequent 3D visualization.

2.1.2. Feature Extraction and Selection

From each Region of Interest (ROI) corresponding to an individually segmented vertebra, a comprehensive set of quantitative radiomic features was extracted to characterize the underlying bone tissue. Feature extraction was performed using the open-source PyRadiomics library (version 3.1.0) [

30], which enables automated, standardized, and reproducible computation of a broad range of descriptors from medical imaging data.

For each vertebra, 107 radiomic features were extracted and categorized according to standard radiomic taxonomy as follows: First-order features, describing the statistical distribution of voxel intensities within the vertebral volume (examples are mean intensity, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, energy, and entropy); Morphological features, quantifying 3D geometric properties of the vertebra, such as volume, surface area, maximum diameters, compactness, and sphericity; and Textural features, derived from the Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM), Gray Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM), Gray Level Size Zone Matrix (GLSZM), Gray Level Dependence Matrix (GLDM), and Neighboring Gray Tone Difference Matrix (NGTDM). These features capture intra-vertebral heterogeneity, spatial relationships between gray levels, and local structural organization within the bone matrix. Such descriptors are widely adopted in oncologic radiomics as quantitative biomarkers for characterizing lesion morphology and tissue composition, with established correlations to clinical and histopathological parameters [

31].

Given the high dimensionality and potential redundancy of the extracted features, a two-step feature selection strategy was adopted. First, a correlation-based filtering procedure was applied to mitigate multicollinearity and reduce noise in the dataset. Features exhibiting a Pearson correlation coefficient greater than 0.95 were considered redundant and consequently excluded, finally resulting in 67 non-redundant features.

Following correlation-based filtering, a supervised feature selection step was conducted to further refine the radiomic feature space and identify the most discriminative descriptors for classification. This process was based on a Random Forest (RF) model trained on the balanced dataset to compute feature importance scores derived from the mean decrease in Gini impurity across all decision trees. The 30 most informative features were retained according to their relative importance ranking, representing those with the highest contribution to distinguishing metastatic from healthy vertebrae.

Table 1 lists the selected radiomic features together with their corresponding importance scores.

The resulting feature set constituted a refined radiomic representation for each vertebra, comprising 30 non-redundant optimized for subsequent classification tasks while preserving clinically interpretable descriptors that capture both the morphological and textural heterogeneity of vertebral bone tissue.

2.1.3. Dataset Balancing and Sampling Strategy

The original dataset exhibited a pronounced class imbalance, with a substantial predominance of healthy vertebrae compared to metastatic vertebrae. Such an imbalance can adversely affect the performance of supervised learning algorithms, leading the classifier to favor the majority class and thereby reducing its ability to correctly identify metastatic cases.

To mitigate this issue, a guided undersampling strategy of the healthy class was adopted with the aim of retaining the most informative and discriminative samples while minimizing redundancy, thus reducing the proportion of healthy to metastatic vertebrae to a maximum ratio of 1.5:1. Specifically, the Euclidean distance between each healthy vertebra and all metastatic vertebrae was computed in the radiomic feature space. The healthy samples were then ranked based on their average proximity to the metastatic cluster, and only those vertebrae most radiologically similar to the metastatic cases were retained for inclusion in the final dataset. This approach draws inspiration from the NearMiss family of undersampling methods [

32], which prioritize the selection of majority-class instances that are most similar to the minority-class samples. By preserving the healthy vertebrae that are closest, in terms of radiomic profile, to the metastatic ones, the classifier is encouraged to focus on subtle interclass variations rather than on global feature differences. This, in turn, enhances both the sensitivity and specificity of the model, improving its generalization capacity in distinguishing healthy from metastatic vertebrae. Finally, to verify that the undersampling procedure did not distort the representation of healthy anatomy, post-hoc analyses were performed comparing the retained and discarded healthy vertebrae. First, it was verified that the subset of retained healthy vertebrae preserved the anatomical heterogeneity of the original dataset across cervical, thoracic, and lumbar levels. Second, comparison of Euclidean distances in the radiomic feature space confirmed that the retained healthy vertebrae were, as expected, closer to the metastatic cluster than the discarded ones, consistent with the design of the guided undersampling procedure. However, a Mann–Whitney U test showed that this difference was not statistically significant (

p-value = 0.088), suggesting that the method does not induce substantial sampling bias or collapse the natural variability of healthy anatomy. These results indicate that undersampling refines class boundaries without distorting the underlying radiomic structure of the dataset.

At the conclusion of this step, a more balanced dataset was obtained, consisting of 252 healthy and 168 metastatic vertebrae, while retaining those healthy samples exhibiting the highest radiomic similarity to the metastatic class. This approach ensured the preservation of the most discriminative instances within the healthy group, thereby enhancing the dataset’s overall informative value for the subsequent classification task. The final dataset was randomly partitioned, at an 80:20 ratio, into a training set (337 vertebrae) and a test set (83 vertebrae), ensuring stratification by lesion class, ensuring that both training and test sets reflected the same distribution of healthy and metastatic vertebrae as the overall dataset.

2.2. Classification Pipeline

A set of supervised ML algorithms was implemented and systematically compared to identify the most suitable approach for the binary classification of vertebrae as healthy or metastatic. The classifiers were selected based on their consolidated application in medical imaging, as well as their robustness in low-data regimes and their ability to generalize effectively when trained on limited feature sets. Specifically, four models were implemented via the open-source

scikit-learn library (version 1.7) [

33] and evaluated: Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). Logistic Regression was considered as a linear baseline model, providing interpretable coefficients and probabilistic outputs that are readily understandable in a clinical context. The SVM was included as a robust non-linear classifier capable of constructing non-linear decision boundaries through kernel transformations, making it particularly effective for high-dimensional datasets with limited sample size. RF was selected for its ensemble-based stability, reduced sensitivity to noise, and resilience to feature correlation-characteristics that are particularly advantageous when working with handcrafted radiomic descriptors [

22]. Finally, XGBoost was incorporated to assess whether a more complex gradient-boosted approach could further enhance performance by modeling intricate feature interactions, despite the constraints imposed by the limited dataset size.

All models were trained within a unified ML pipeline designed to ensure methodological consistency and fair comparison across classifiers. The pipeline comprised an initial feature normalization step using the StandardScaler (version 0.5), which standardized all radiomic features to zero mean and unit variance, followed by an optional dimensionality reduction stage based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA). When enabled, PCA retained 95% of the explained variance, thereby reducing redundancy while preserving the most informative components of the feature space. The final stage of the pipeline consisted of the supervised learning algorithm, whose parameters were optimized and evaluated on the processed data. Each model’s hyperparameters were optimized via grid search with 5-fold stratified cross-validation, ensuring class balance within each fold. The parameter grids included, depending on the classifier, the number of estimators (trees), maximum tree depth, and minimum samples per split (for tree-based methods); the kernel type, regularization parameter (C), and gamma coefficient (for SVM); the learning rate and number of boosting rounds (for XGBoost); and the number of PCA components retained. The optimization objective was to maximize the mean Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC AUC) across validation folds. The resulting best configurations showed that Random Forest and XGBoost achieved optimal performance without PCA, consistent with their robustness to multicollinearity and their ability to operate effectively in the original feature space. In contrast, Logistic Regression and SVM benefited from PCA, with both selecting a configuration retaining 95% of the explained variance, reflecting their sensitivity to feature dimensionality and correlation. Following hyperparameter tuning, each model was retrained using the optimal configuration and evaluated on an independent hold-out test set. Performance was assessed through multiple quantitative metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC AUC.

2.3. Virtual Reality Visualization

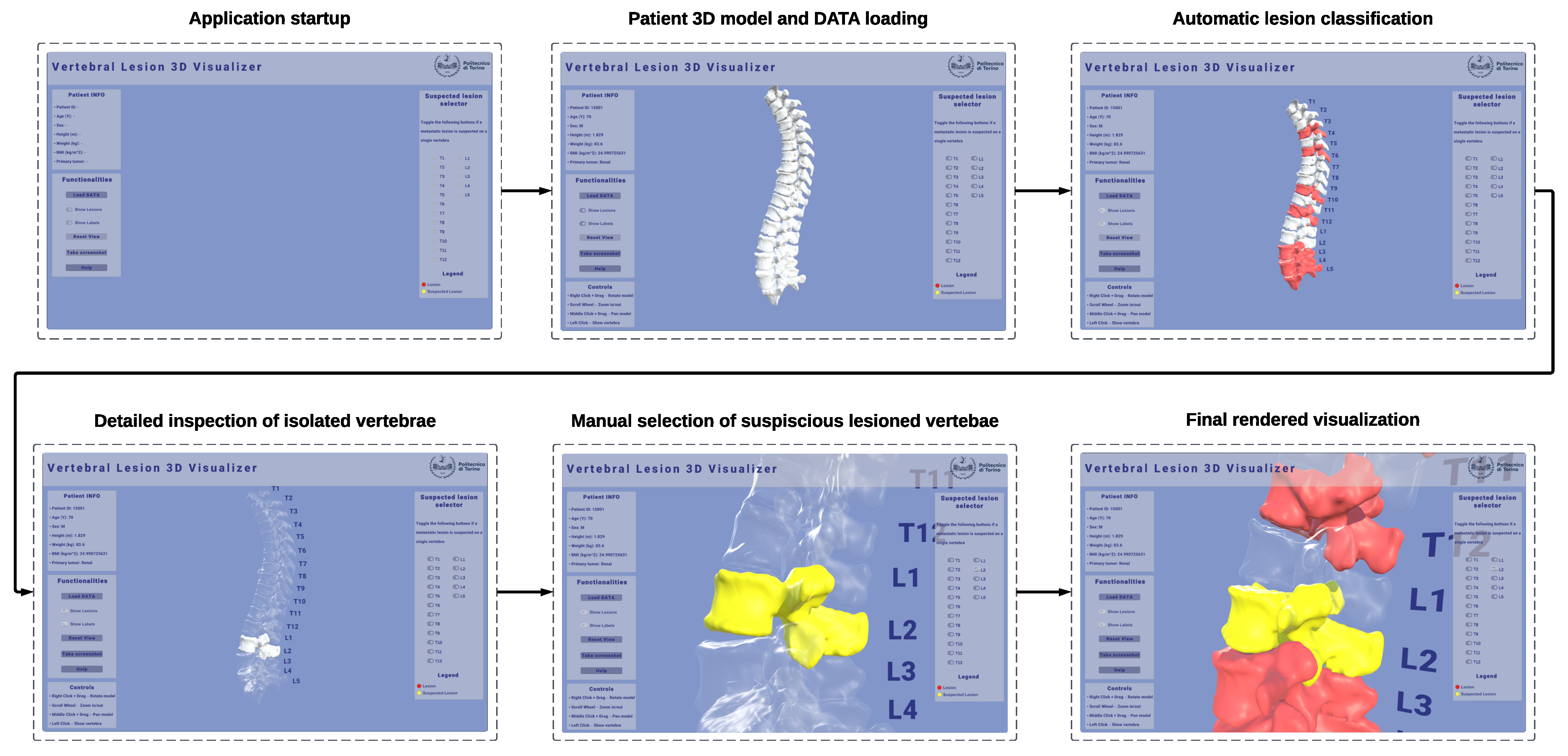

A non-immersive VR desktop application was developed and implemented in Unity 3D (version 6000.1.1f1) to provide an interactive 3D visualization of patient-specific spinal models reconstructed from CT data. The visualization module was conceived as a diagnostic support tool to enhance the interpretability and qualitative assessment of the ML classification results by allowing side-by-side visual comparison between the automatically labeled vertebrae and the clinician’s expert evaluation. The application operates on models derived from patient-specific CT segmentations, preserving the original anatomical geometry and spatial alignment with the source medical images. This ensures that the visualization environment accurately reflects the patient’s real anatomy, allowing the computational predictions to be explored and verified within their true radiological context. Moreover, this visual component is intended not only to enhance the interpretability of the ML predictions but also to improve communication between technical and clinical stakeholders by translating computational outputs into anatomically meaningful representations. An example of the interactive 3D visualization of a patient-specific spine in the VR desktop application can be seen in

Figure 3.

The visualization pipeline involved the conversion of segmented vertebral masks from DICOM-SEG files into triangulated surface meshes, ensuring the preservation of geometric fidelity and spatial alignment with respect to the original CT coordinate system. Each vertebra was reconstructed independently using a marching-cubes algorithm, followed by smoothing and normal recalculation to enhance surface quality while maintaining anatomical accuracy. DICOM metadata, such as origin, spacing, and orientation, were retained during mesh generation to ensure consistent registration of all vertebrae within the same spatial reference frame. Moreover, the resulting meshes retain the vertebra identifier, enabling unambiguous linkage to the corresponding radiomic feature vector and classifier output. The reconstruction process of vertebrae 3D models reconstruction can be visualized in

Figure 4.

The workflow followed in the Unity 3D application can be visualized in

Figure 5.

The resulting patient-specific meshes were then imported into the Unity 3D environment and assembled into a full 3D model of the spine, preserving the relative anatomical positions of adjacent structures. Each vertebra mesh is automatically annotated with the binary class predicted by the classification model and rendered with a per-class color map, highlighting in neutral gray the vertebrae predicted as healthy, and in red the vertebrae predicted as metastatic by the classifier. To explicitly support the clinician’s interpretive role, a dedicated review mode enables clinicians to examine the spine vertebra-by-vertebra, compare automatic labels with their own assessment, and override or flag cases of interest. Through the interface, it is possible to manually mark vertebrae that the user suspects may be injured, dynamically highlighting them in yellow. This dual annotation process (automatic prediction alongside expert reporting) can be recorded during execution and exported for downstream verification and analysis.

The application targets typical VR interaction on desktops with a mouse and/or keyboard to ensure broad deployability in hospital IT settings without requiring specialized visualization devices, such as a head-mounted display. The interface supports camera orbit, pan, and zoom around the global spine or a selected vertebra; selection and isolation of single vertebrae; cut-plane toggles for contextual inspection; and opacity/visibility controls for layers (e.g., all healthy vs. predicted metastatic). The design intent is to complement, not replace, clinical judgment: visual coding and interactions are deliberately simple, emphasizing traceability (which vertebra, which label, why) and explainability, linking decisions to information at the level of features, which can be directly displayed in the user interface.

3. Results

Four supervised classification models were trained and evaluated to identify the most effective approach for vertebral lesion detection.

Table 2 reports the comparative performance of the tested algorithms on the independent test set.

Among the evaluated classifiers, the Random Forest (RF) model achieved the highest overall performance, with accuracy (0.86), F1-score (0.85), and AUC-ROC (0.91) outperforming all other approaches. The classifier also exhibited a well-balanced relationship between precision (0.85) and recall (0.84), indicating its ability to detect metastatic vertebrae reliably while maintaining a limited rate of false positives. These results confirm the robustness of RF in handling structured radiomic features and class imbalance, consistent with evidence from previous radiomics studies in oncologic imaging. XGBoost demonstrated competitive results, with accuracy (0.84), F1-score (0.84), and AUC-ROC (0.89) approaching those of the RF model. However, its slightly reduced recall (0.83) suggests a moderate tendency to miss part of the metastatic class. The SVM classifier showed lower performance across all metrics, achieving an accuracy of 0.73 and an F1-score of 0.73. Although precision (0.73) was comparable to recall (0.75), the overall discriminative capacity remained inferior to RF and XGBoost, as reflected by its AUC-ROC of 0.89. Logistic Regression yielded the lowest overall performance, with accuracy (0.75) and AUC-ROC (0.80), likely reflecting the limitations of linear decision boundaries in capturing the complex radiomic patterns underlying spinal metastases.

In view of these results, the RF model was selected as the final classifier for subsequent analyses and 3D visualization, as it offered the optimal balance between predictive performance, robustness, and clinical interpretability, in accordance with prior evidence from oncologic imaging studies [

31].

Table 3 reports the class-wise performance metrics of the RF classifier evaluated on the independent test set.

For the metastatic class (1), the model reached an F1-score of 0.81, with a precision of 0.84 and a recall of 0.79, indicating that most metastatic vertebrae were correctly identified, with a moderate rate of false negatives. For the healthy class (0), the classifier achieved higher values (F1-score of 0.88, precision of 0.87, and recall of 0.90), demonstrating slightly better performance in recognizing non-pathological vertebrae. This behavior is consistent with typical radiomic classification tasks in which metastatic lesions represent the minority class and exhibit higher intraclass heterogeneity. Despite this inherent difficulty, the RF model demonstrated satisfactory sensitivity in detecting metastatic vertebrae, while maintaining high precision and overall stability, making it a suitable model for subsequent feature interpretation and visualization within the developed framework.

To provide a more detailed view of the RF classifier’s predictions,

Figure 6 reports the confusion matrix computed on the independent test set.

The RF classifier correctly predicted the condition of 71 out of 83 vertebrae (86%), yielding a balanced distribution of true positives and true negatives. Specifically, 26 metastatic vertebrae were correctly detected (true positives), while 7 were misclassified as healthy (false negatives). Conversely, 45 healthy vertebrae were correctly identified (true negatives), with 5 false positives. The limited number of false negatives indicates that most metastatic vertebrae were successfully recognized, although some cases of borderline radiomic profiles were erroneously labeled as healthy. This outcome reflects the intrinsic radiological heterogeneity of metastatic lesions, which often exhibit overlapping intensity and texture characteristics with normal bone tissue. Overall, the confusion matrix confirms the robustness and balanced predictive capability of the RF model, in agreement with the quantitative metrics reported in

Table 3.

Figure 7 presents the ROC curve computed for the RF classifier on the independent test set.

The curve exhibits a favorable trade-off between true positive rate (sensitivity) and false positive rate (1 – specificity) across all decision thresholds, with an AUC of 0.91. This value confirms the model’s high discriminative ability and is consistent with the quantitative metrics previously reported in

Table 3. The shape of the ROC curve indicates a stable and well-generalized classifier, capable of effectively distinguishing metastatic from healthy vertebrae while maintaining limited overfitting and robust generalization on unseen data.

The usability of the proposed 3D visualization application was assessed using the System Usability Scale (SUS), a widely adopted and validated standardized questionnaire for the quantitative evaluation of perceived usability in interactive systems [

34]. The SUS consists of ten statements, to which participants indicate their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5). Following the standard scoring procedure, individual item responses were converted into a composite usability score on a 0–100 scale, enabling direct comparison across users and studies [

35]. According to established interpretive guidelines, a SUS score of 68 is generally considered the threshold for above-average usability, with higher scores indicating progressively better user experience [

36].

The questionnaire was administered to 20 participants aged 23–59 after interacting with the proposed application, and both item-level responses and aggregated SUS scores were analyzed. The obtained results, reported in

Table 4, provide quantitative evidence of the system’s usability and support its suitability as an intuitive clinical decision-support and visualization tool. To summarize central tendency and variability, median, minimum, and maximum values were computed for each item, while the overall usability was reported in terms of median and distribution of SUS scores across participants.

The application achieved a median SUS score of 83.75, which corresponds to an excellent level of usability according to standard SUS interpretation guidelines. The distribution of scores indicates a consistently positive user experience, with most participants rating the system well above the accepted usability threshold (SUS = 68). Analysis of individual SUS items revealed high agreement for positively worded statements (), indicating perceived ease of use and functional clarity, while negatively worded items showed low scores (), suggesting limited perceived complexity and low cognitive burden. Greater response variability was observed for Items 4, 6, and 8, which address perceived need for technical support, system consistency, and perceived complexity, respectively. These items displayed wider interquartile ranges and a broader spread of responses, reflecting heterogeneous user perceptions across the study population. Despite this variability at the item level, the aggregated SUS scores remained consistently above the standard usability threshold, confirming that the proposed visualization interface is intuitive and accessible, supporting its role as a clinical decision-support and exploration tool rather than a diagnostic replacement.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate an end-to-end radiomics-based framework for the automatic classification of vertebral metastases on CT imaging, complemented by an interactive 3D visualization module to enhance clinical interpretability. By integrating radiomic feature extraction, machine learning classification, and VR-ready rendering of the spine, the proposed system aims to address the challenges posed by the morphological heterogeneity of metastatic lesions and the limited availability of large annotated datasets.

The proposed binary classification system demonstrated promising performance in distinguishing healthy from metastatic vertebrae using radiomic features extracted from segmented CT scans. As summarized in

Table 3, the final model, trained using a RF algorithm and optimized through cross-validation, achieved an overall accuracy of 0.86, an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.91, and an F1-score of 0.81 for the metastatic class. The sensitivity (recall) of 0.79 indicates a satisfactory ability to correctly identify vertebrae affected by metastases, while maintaining a relatively low false-positive rate. The superiority of the RF classifier was confirmed through comparison with other models, as reported in

Table 2.

The confusion matrix shown in

Figure 6 highlights the balance between true positives and false positives, confirming the model’s robustness in handling class imbalance while preserving clinical specificity. Similarly, the ROC curve (

Figure 7) corroborates the model’s strong discriminative capability across different classification thresholds. These findings suggest that the proposed approach could serve as a useful diagnostic support tool, potentially reducing both missed lesions and false-positive cases in clinical evaluation.

The obtained results are particularly relevant given the limited size and pronounced class imbalance of the Spine-METS-CT-SEG dataset [

27], in which only 22% of vertebrae exhibit metastatic lesions. The guided undersampling strategy, based on the Euclidean distance in the radiomic feature space, likely enhanced the model’s discriminative performance by retaining healthy vertebrae most similar to metastatic ones, thereby refining class boundaries. In parallel, feature selection via RF reduced data dimensionality and improved generalizability by eliminating redundant or non-informative variables [

33].

When compared to related studies, the present results are consistent with those achieved by DL approaches, while offering the advantage of greater model interpretability typical of machine learning methods based on handcrafted features. For instance, Koike et al. [

23] developed a two-stage DL framework for the analysis of spinal metastases on CT images. In their pipeline, a YOLOv5m network was first used for vertebral localization, followed by an InceptionV3 model, fine-tuned through transfer learning, for binary classification of osteolytic lesions (presence vs. absence), reporting an AUC of 0.94, accuracy of 95%, and recall of 74%. Although their F1-score (0.83) is comparable with ours (0.85), their system was trained exclusively on lytic lesions, whereas our model encompasses all lesion types osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed), which were initially identified in the dataset, using a binary lesion vs. non-lesion classification. Similarly, Hong et al. [

20] achieved an AUC of 0.96 using an RF-based radiomic model to differentiate osteoblastic metastases from benign bone islands. However, their context was more homogeneous and clinically constrained, focusing solely on sclerotic lesions, and their dataset, collected from multiple institutions, was larger and more diverse. By contrast, our study relied on a single-center public dataset with fewer cases and more limited variability, making the achieved results particularly encouraging.

Despite these methodological differences, the radiomic approach employed in our work demonstrated a good differentiative capacity even with limited data volume. Unlike DL models, which require large quantities of annotated images and often rely on data augmentation to ensure generalization, radiomics-based ML is more suitable for small to medium datasets, offering transparent and reproducible feature interpretation. One of the main strengths of our approach lies in the transparency and interpretability of the decision-making process: the features selected by Random Forest are well-established quantitative metrics in the literature and related to structural and textural properties of vertebrae [

30], enabling a more direct understanding of the classification drivers and facilitating integration into clinical workflows.

For these reasons, the results presented here should not be interpreted as competitive benchmarks relative to heterogeneous DL pipelines, but rather as evidence that a carefully designed radiomics-based workflow can achieve clinically meaningful performance even in data-constrained scenarios. In this context, our findings should be viewed as a demonstration of methodological feasibility rather than a head-to-head comparison with deep-learning approaches, whose performance is known to depend strongly on large-scale, diverse datasets, extensive preprocessing, and task-specific architectural tuning. The fact that the proposed model attains robust classification accuracy despite substantial differences in dataset size, lesion composition, and imaging heterogeneity relative to prior studies indicates that radiomics-based methods remain a valuable and pragmatic alternative in settings where data scarcity or annotation limitations preclude the effective deployment of deep neural networks.

Beyond quantitative performance, an important contribution of this study is the development of an interactive 3D visualization module in Unity 3D, which enables clinicians to explore the reconstructed spine and the model’s predictions within a virtual environment. Although interaction occurs via keyboard and mouse, the system is already structured to support future deployment on immersive head-mounted displays. This component adds an additional layer of clinical interpretability that is often absent in conventional machine learning pipelines. By visualizing each vertebra in its anatomical context, with color-coded labels indicating predicted metastatic involvement, clinicians can intuitively assess model outputs, inspect spatial relationships between lesions, and compare automatic predictions with their own judgment, especially in cases with subtle or ambiguous radiologic patterns. Moreover, the optional manual annotation capability, allowing physicians to highlight vertebrae they consider potentially metastatic, facilitates human–AI collaboration, positioning the visualization module not as a replacement for expert evaluation but as a complementary decision-support tool.

Importantly, the inclusion of a formal usability assessment addresses a critical aspect of clinical translation. The SUS results demonstrate that the proposed visualization tool is not only technically feasible but also perceived as usable and intuitive by end users. This supports the claim that the Unity-based 3D visualization module can effectively complement the automated classification pipeline by improving interpretability without introducing additional complexity into the clinical workflow. However, item-level analysis revealed higher variability in SUS items related to perceived ease of use, system consistency, and the need for technical support. This dispersion suggests heterogeneous user perceptions, likely influenced by differences in prior familiarity with 3D visualization environments and advanced interactive interfaces. Such variability is common in spatial and VR-ready applications and highlights the importance of targeted onboarding and training to ensure consistent adoption across users with varying technical backgrounds.

Nevertheless, the study presents certain limitations that constrain its direct clinical applicability. The primary limitation concerns the dataset size and imbalance: although the Spine-METS-CT-SEG collection provides accurate segmentations and reliable annotations, it contains only 765 vertebrae from 54 patients, all acquired from a single institution. This restricted sample limits the diversity of imaging protocols, scanner types, and patient populations represented in the dataset, potentially reducing the generalizability of the model to broader clinical settings. As the publicly available dataset does not include an external cohort, an independent external validation was not feasible in the present study. This is particularly relevant considering that radiomic features are known to be sensitive to variations in segmentation precision, acquisition parameters, and reconstruction settings, potentially affecting reproducibility across scanners and institutions. Although a dedicated robustness analysis was not performed, methodological safeguards, such as removing highly correlated features and selecting predictors via Random Forest importance, were adopted to mitigate variability. Nonetheless, feature stability remains an important consideration and warrants further investigation in future studies.

A second limitation is inherent to the binary classification scheme (healthy vs. metastatic), which does not differentiate among osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed lesions, which differ substantially in etiology, biological behavior, and clinical implications. Collapsing them into a single metastatic class reduces the granularity of the prediction. This choice was driven partly by clinical considerations, since, in routine diagnostic workflows, the primary need is to identify the presence of metastatic involvement, with subtype characterization typically performed subsequently by radiologists, and partly by dataset constraints. In the Spine-METS-CT-SEG collection, metastatic vertebrae account for only 22% of all samples, and the individual subtypes are highly imbalanced, with some classes represented by fewer than ten instances, rendering multi-class training statistically unreliable. Moreover, radiomic features of osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed lesions often exhibit substantial overlap, reflecting the continuum of bone remodeling patterns observed in metastatic disease. With limited data per class, such overlap impedes the model’s ability to learn stable and discriminative boundaries between subtypes. Additionally, lesions with mixed or borderline characteristics introduce ambiguity in manual segmentation, contributing to uncertainty in ground truth labeling. For these reasons, the present framework should be interpreted as an automatic screening tool rather than a definitive lesion characterization system.

Based on these observations, several directions for future development are outlined. First, extending the framework to multi-class classification would allow finer stratification of lesion types, providing more clinically useful insights for treatment planning, for example, in assessing fracture risk or choosing targeted systemic or radiotherapy therapies. Future developments will also focus on validating the proposed framework on larger, multi-center datasets that encompass greater variability in scanners, acquisition protocols, and patient populations. This will enable a more rigorous assessment of model generalizability and radiomic feature robustness across heterogeneous imaging environments. Moreover, integration with immersive Extended Reality (XR) environments represents a promising opportunity. The existing VR visualization module could be easily expanded into an interactive 3D diagnostic environment accessible via immersive XR headsets, enabling clinicians to explore, annotate, and analyze vertebral lesions in real time. Such environments may enable more immersive visualization and a more natural interaction with 3D anatomical structures and could prove valuable both for preoperative planning and educational purposes, particularly in complex oncologic cases involving multiple vertebral levels. Finally, incorporating longitudinal post-treatment data could support the development of predictive models for monitoring lesion progression, evaluating therapeutic response, and detecting early recurrences or complications.