Gaussian Process Modeling of EDM Performance Using a Taguchi Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

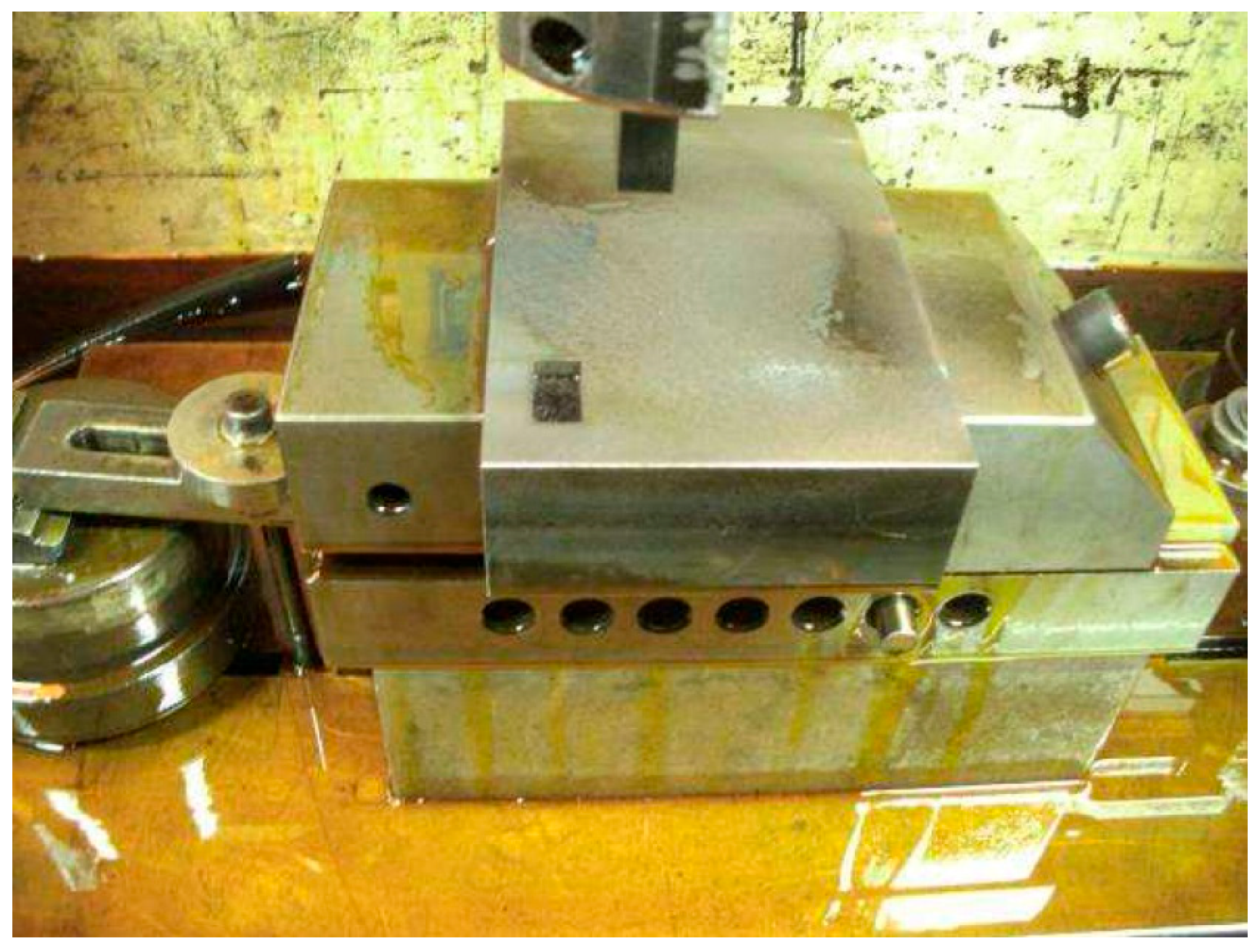

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Taguchi Design

2.3. Gaussian Process Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GPR Configuration and Learned Hyperparameters

3.2. Predictive Accuracy and Validation

3.3. Parameter Influence Analysis (ARD)

3.4. Multi-Objective Decision Analysis

3.5. Limitations and Practical Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tufail, M.; Giri, J.; Makki, E.; Sathish, T.; Chadge, R.; Sunheriya, N. Machinability of different cutting tool materials for electric discharge machining: A review and future prospects. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 040702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z. A hybrid process model for EDM based on finite-element method and Gaussian process regression. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 74, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanić, P.; Dučić, N.; Stanković, N. Development of Artificial Neural Network models for vibration classification in machining process on Brownfield CNC machining center. J. Prod. Eng. 2024, 27, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, R.; Vignesh, M.; Pugazhenthi, R.; Anbuchezhiyan, G.; Satyanarayana Gupta, M. Effect of process parameter on wire cut EDM using RSM method. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 2024, 18, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, J.; Shrivastava, S. Fuzzy based multi-response optimization: A case study on EDM machining process. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, I.; Alsakarneh, A. Machine learning-based prediction of EDM material removal rate and surface roughness. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Saleh, T.; Sophian, A.; Rahman, M.A.; Huang, T.; Mohamed Ali, M.S. Experimental modeling techniques in electrical discharge machining (EDM): A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 2125–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemalatha, S.; Anusha, K. Optimization of machining parameters material removal rate and surface roughness by using reponse surface methodology and Grey Taguchi technique on Electric Discharge Machine. Next Mater. 2025, 6, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samantra, C.; Barua, A.; Pradhan, S.; Kumari, K.; Pallavi, P. Parametric investigation of die-sinking EDM of Ti6Al4V using the hybrid Taguchi-RAMS-RATMI method. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yin, C.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Ming, W.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K. Optimization of EDM process parameters based on variable-fidelity surrogate model. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 2031–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X. Predicting the material removal rate during electrical discharge diamond grinding using the Gaussian process regression: A comparison with the artificial neural network and response surface methodology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 113, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjaiah, M.; Laubscher, R.F.; Kumar, A.; Basavarajappa, S. Parametric optimization of MRR and surface roughness in wire electro discharge machining (WEDM) of D2 steel using Taguchi-based utility approach. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2016, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, T.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, R.D. Material removal rate, electrode wear rate, and surface roughness evaluation in die sinking EDM with hollow tool through response surface methodology. Int. J. Manuf. Eng. 2014, 2014, 259129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemitaheri, M.; Mekarthy, S.M.R.; Cherukuri, H. Prediction of specific cutting forces and maximum tool temperatures in orthogonal machining by support vector and Gaussian process regression methods. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 48, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, G.; Cao, Y.; Shen, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Ming, W. Development of a hybrid intelligent process model for micro-electro discharge machining using the TTM-MDS and gaussian process regression. Micromachines 2022, 13, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, U.; Klink, A.; Bergs, T. Data-driven model for process evaluation in wire EDM. CIRP Ann. 2023, 72, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shastri, R.K.; Mohanty, C.P.; Dash, S.; Gopal, K.M.P.; Annamalai, A.R.; Jen, C.-P. Reviewing performance measures of the die-sinking electrical discharge machining process: Challenges and future scopes. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, T.; Fang, M. Reliable multi-objective optimization of high-speed WEDM process based on Gaussian process regression. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2008, 48, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM A681; Standard Specification for Tool Steels Alloy. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Rodić, D.; Gostimirović, M.; Sekulić, M.; Savković, B.; Aleksić, A. Fuzzy logic approach to predict surface roughness in powder mixed electric discharge machining of titanium alloy. Stroj. Vestn.-J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 69, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, S.A.; Pardo, Y.A. Empirical Modeling and Data Analysis for Engineers and Applied Scientists; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- El Majdoub, W.; Hamza Daud, M.; Sztankovics, I. Form accuracy and cutting forces in turning of X5CrNi18-10 shafts: Investigating the influence of thrust force on roundness deviation under low-feed machining conditions. J. Prod. Eng. 2025, 28, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, J.; Berger, J.; Dawid, A.; Smith, A. Regression and classification using Gaussian process priors. Bayesian Stat. 1998, 6, 475. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.K.; Rasmussen, C.E. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Paananen, T.; Piironen, J.; Andersen, M.R.; Vehtari, A. Variable selection for Gaussian processes via sensitivity analysis of the posterior predictive distribution. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Okinawa, Japan, 16–18 April 2019; pp. 1743–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Koehler, A.B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 2006, 22, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Gupta, K.K.; Maity, S.R.; Dey, S. Data-driven probabilistic performance of Wire EDM: A machine learning based approach. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 236, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Cheng, G.; Fan, Y. Research on surface roughness prediction in turning Inconel 718 based on Gaussian process regression. Phys. Scr. 2022, 98, 015216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, H.-P.; Herms, R.; Juhr, H.; Schaetzing, W.; Wollenberg, G. Comparison of measured and simulated crater morphology for EDM. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 149, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, F.L.; Weingaertner, W.L. The behavior of graphite and copper electrodes on the finish die-sinking electrical discharge machining (EDM) of AISI P20 tool steel. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2007, 29, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabgard, M.; Ahmadi, R.; Seyedzavvar, M.; Oliaei, S.N.B. Mathematical and numerical modeling of the effect of input-parameters on the flushing efficiency of plasma channel in EDM process. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2013, 65, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgassim, O.; Abusada, A. Optimization of the EDM parameters on the surface roughness of AISI D3 tool steel. In Proceedings of Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Istanbul, Turkey, 3–6 July 2012; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ishfaq, K.; Sana, M.; Waseem, M.U.; Ashraf, W.M.; Anwar, S.; Krzywanski, J. Enhancing EDM machining precision through deep cryogenically treated electrodes and ANN modelling approach. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Machining Parameter | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tool material | Copper | Graphite | - |

| Discharge current, Ie (A) | 5 | 9 | 13 |

| Pulse duration, ti (µs) | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| No. | Tool Material | Discharge Current (A) | Pulse Duration (µs) | Surface Roughness (µm) | Material Removal Rate (mm3/min) | Overcut (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Copper | 13 | 7 | 9.7 | 10.71 | 0.2 |

| 2. | Copper | 5 | 7 | 5.1 | 4.31 | 0.105 |

| 3. | Copper | 5 | 2 | 4.2 | 4.16 | 0.095 |

| 4. | Copper | 13 | 5 | 9.4 | 18.71 | 0.18 |

| 5. | Copper | 9 | 2 | 8.2 | 7.71 | 0.13 |

| 6. | Copper | 13 | 2 | 9.2 | 6.13 | 0.165 |

| 7. | Copper | 9 | 5 | 8.8 | 14.89 | 0.14 |

| 8. | Copper | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9.49 | 0.155 |

| 9. | Copper | 5 | 5 | 5.1 | 6.47 | 0.1 |

| 10. | Graphite | 9 | 5 | 7.9 | 20.78 | 0.13 |

| 11. | Graphite | 5 | 7 | 5.4 | 6.32 | 0.095 |

| 12. | Graphite | 9 | 2 | 6.3 | 12.05 | 0.11 |

| 13. | Graphite | 13 | 5 | 9 | 33.06 | 0.17 |

| 14. | Graphite | 13 | 2 | 8.5 | 18.36 | 0.14 |

| 15. | Graphite | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8.28 | 0.095 |

| 16. | Graphite | 13 | 7 | 9.5 | 30.05 | 0.19 |

| 17. | Graphite | 9 | 7 | 8.8 | 17.51 | 0.15 |

| 18. | Graphite | 5 | 2 | 4.2 | 4.55 | 0.09 |

| Output | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | 0.976 | 3.737 | 3.361 | 2.261 | 0.103 |

| MRR | 2.934 | 1.790 | 1.533 | 15.241 | 0.185 |

| OC | 2.449 | 4.676 | 7.778 | 0.058 | 0.003 |

| i | α_Ra | α_MRR | α_OC | i | α_Ra | α_MRR | α_OC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m = 0 | m = 1 | ||||||

| 1. | 1.894 | −0.181 | 144.764 | 10. | −0.313 | 0.009 | −20.318 |

| 2. | −2.714 | −0.009 | 189.880 | 11. | 4.211 | 0.015 | −143.862 |

| 3. | −1.034 | 0.002 | 17.936 | 12. | −4.049 | 0.001 | −220.082 |

| 4. | −2.011 | 0.018 | −221.721 | 13. | 1.015 | 0.061 | 83.604 |

| 5. | 5.910 | 0.017 | 269.903 | 14. | −0.533 | 0.145 | −310.265 |

| 6. | 3.059 | −0.117 | 387.284 | 15. | −4.584 | 0.019 | 45.951 |

| 7. | −1.921 | 0.015 | −78.074 | 16. | 1.610 | 0.226 | −11.984 |

| 8. | 0.631 | 0.007 | −19.800 | 17. | 2.321 | 0.004 | 106.992 |

| 9. | 3.634 | −0.005 | −93.196 | 18. | 1.949 | 0.004 | 16.461 |

| Response | RMSE | MAE | RMSE (% of Range) | MAE (% of Range) | Response Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | 0.53686 | 0.40784 | 9.7611 | 7.4153 | 5.5 |

| MRR | 1.5625 | 1.2065 | 5.4067 | 4.1748 | 28.9 |

| OC | 0.0065125 | 0.005479 | 5.9205 | 4.9809 | 0.11 |

| wI | wt | wm | lI | lt | lm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | 0.644 | 0.168 | 0.187 | 0.976 | 3.737 | 3.361 |

| MRR | 0.220 | 0.360 | 0.420 | 2.934 | 1.790 | 1.533 |

| OC | 0.544 | 0.285 | 0.171 | 2.449 | 4.676 | 7.778 |

| Ie [A] | ti [µs] | Material | Ra (µm) | MRR (mm3/min) | OC (mm) | RaSD | MRRSD | OCSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.00 | 2.0 | Graphite | 4.179 | 4.5472 | 0.088462 | 0.14251 | 0.26054 | 0.0041408 |

| 5.96 | 3.8 | Graphite | 5.0649 | 10.139 | 0.096409 | 0.39553 | 0.81580 | 0.0038061 |

| 6.12 | 3.7 | Graphite | 5.1100 | 10.420 | 0.097279 | 0.43342 | 0.85348 | 0.0038135 |

| 8.68 | 3.8 | Graphite | 7.0265 | 17.953 | 0.119540 | 0.17796 | 0.81158 | 0.0037694 |

| 8.36 | 4.3 | Graphite | 7.0289 | 17.999 | 0.119610 | 0.26483 | 0.55891 | 0.0037679 |

| 8.52 | 4.1 | Graphite | 7.0553 | 18.147 | 0.119900 | 0.21968 | 0.67045 | 0.0037671 |

| Role | Ie (A) | ti (µs) | Material | Ra (µm) | MRR (mm3/min) | OC (mm) | RaSD | MRRSD | OCSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Ra | 5.00 | 2.00 | Graphite | 4.179 | 0.143 | 4.547 | 0.261 | 0.088 | 0.004 |

| High-MRR | 8.47 | 4.17 | Graphite | 7.047 | 0.235 | 18.108 | 0.634 | 0.120 | 0.004 |

| Knee | 6.07 | 3.67 | Graphite | 5.069 | 0.421 | 10.223 | 0.864 | 0.097 | 0.004 |

| Low-Ra | 4.84 | 1.90 | Copper | 4.171 | 0.167 | 3.817 | 0.313 | 0.096 | 0.004 |

| Low-OC | 4.84 | 2.75 | Copper | 4.399 | 0.157 | 4.937 | 0.782 | 0.096 | 0.004 |

| High-MRR | 5.36 | 4.05 | Copper | 5.014 | 0.211 | 7.263 | 0.698 | 0.101 | 0.004 |

| Knee | 4.84 | 3.33 | Copper | 4.546 | 0.157 | 5.559 | 0.922 | 0.096 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodić, D.; Sekulić, M.; Savković, B.; Aleksić, A.; Kosanović, A.; Blagojević, V. Gaussian Process Modeling of EDM Performance Using a Taguchi Design. Eng 2026, 7, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010014

Rodić D, Sekulić M, Savković B, Aleksić A, Kosanović A, Blagojević V. Gaussian Process Modeling of EDM Performance Using a Taguchi Design. Eng. 2026; 7(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodić, Dragan, Milenko Sekulić, Borislav Savković, Anđelko Aleksić, Aleksandra Kosanović, and Vladislav Blagojević. 2026. "Gaussian Process Modeling of EDM Performance Using a Taguchi Design" Eng 7, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010014

APA StyleRodić, D., Sekulić, M., Savković, B., Aleksić, A., Kosanović, A., & Blagojević, V. (2026). Gaussian Process Modeling of EDM Performance Using a Taguchi Design. Eng, 7(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010014