A Systematic Methodology for Design in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing Derived by a Reverse-Traced Workflow

Abstract

1. Introduction

- •

- (RQ1) How can parts be consolidated without compromising the independence of functional requirements?

- •

- (RQ2) Which criteria should govern part merging, and to what extent are these criteria generalizable across applications?

- •

- (RQ3) How should functional integration rules be applied at each phase of the design process?

- •

- (RQ4) At what points in the workflow do these integration rules most effectively ensure both performance and manufacturability?

2. Methodology and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conventional Design Process

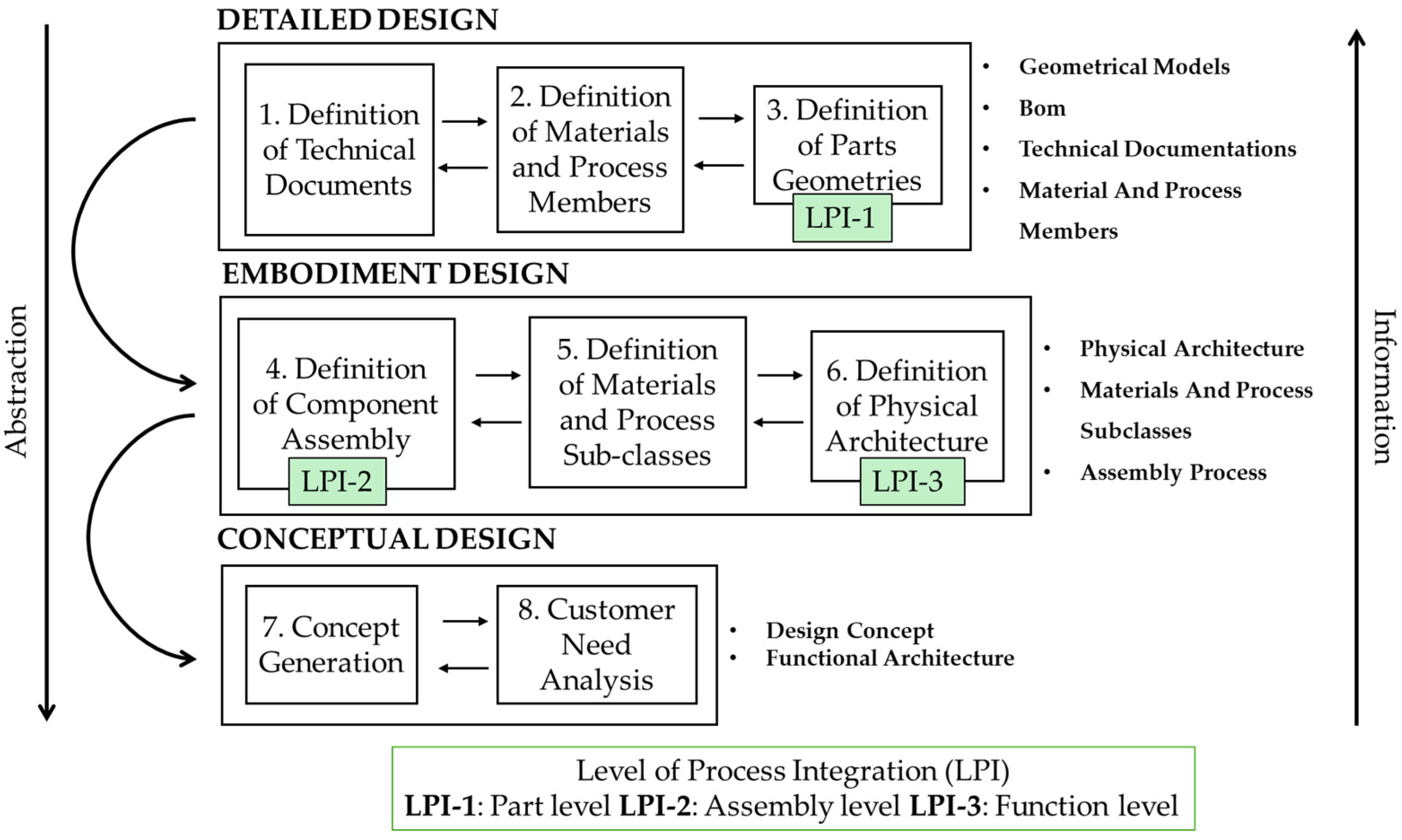

- The conceptual design phase begins with the needs analysis phase that gathers customer requirements (CRs) and project constraints and defines the functional requirements (FRs) and nonfunctional requirements (NFRs) of the product [25,26]. FRs specify what the product must do, and NFRs express how well the product should perform its functions, including constraints such as reliability, maintainability, usability, performance thresholds, and compliance requirements from legislation and standards. Design Criteria (DCs) are constructed from NFRs as measurable, quantifiable specifications that operationalize each NFR into explicit targets or thresholds. DCs form the fundamental basis for design decision-making across all design phases and enable systematic trade-offs and traceability. The concept generation phase serves as a bridge between understanding the problem and defining viable solutions. This process translates FRs into functions and explores solutions as a combination of working principles that address those functions. The functions can be seen as a black box that processes flows. Those flows connect functions and can be described as a flow of signal, material, and energy. The network of functions connected by flows refers to a structure. Based on the abstraction levels, the structure can be detailed and narrow the solution space. Indeed, begin with high-level functions that are decomposed into sub-functions based on the context and constraints, thereby reducing the level of abstraction. This decomposition enables the refinement of solutions, whereby the sub-functions are associated with physical or digital entities called design parameters (DPs) [19,20,27,28]. DPs are defined as parameters that govern the solutions, enabling satisfaction of the specified FRs. This process refers in the literature to Functional Modeling [29], and the functions and flows can be described using ontology as the Functional Basis proposed by Stone et al. [30]. When solutions are defined using function-flow pairs, they can be translated into mathematical forms for analysis, providing neutral comparison methods for different solutions. The output of this phase is a concept with its functional architecture and DPs.

- The embodiment design phase [23] translates functional architecture into physical architecture by defining spatial arrangement, interfaces, materials, and manufacturing processes for each product component. Physical architecture development follows three main stages: allocating functions to components through activities such as function sharing and combination; defining functional interfaces and spatial arrangements using bounding volumes and geometric envelopes; and implementing auxiliary functions (e.g., thermal management, environmental protections, and maintenance). Functions to components are basically the association of the functions with the components that physically or digitally realize them. In this stage, the notion of a module is defined. There can be two main situations in the creation of modules in the product: the association of one function to one component (modular architecture) and the association of multiple functions to one component (integral architecture). Different perspectives can be used for this allocation decision, such as supply chain or product variety, but among them, two distinct methods are based on a function’s perspective. Function sharing joins similar functions into a shared DP when they handle similar flows and targets under matching DCs. Whereas, function combination integrates distinct functions into the same component, assigning multiple DPs before finalizing spatial arrangements. Functional interfaces, which may passively transmit or actively transform flows, also establish component positioning and orientation. Interfaces can be classified according to interaction type [31]: through-flow, in which the flow passes through the interface unchanged; diverging flow, in which the flow is split or separated; or converging flow, in which multiple flows are combined. Material and manufacturing process selection involves a bidirectional trade-off with the definition of the physical architecture; the function defines material property regions, materials constrain process options, and process choice determines shape, size, quality, and cost. Process variables (PVs), material and process selections, are progressively defined across embodiment and detailed design phases: at embodiment design, process and material subclasses are selected; at detailed design, process and material members (e.g., layer thickness, build orientation, specific material grade, processing conditions) are specified. Finally, component consolidation strategies evaluate geometric adjacency, relative motion, process subclass, and material compatibility to merge, embed, or assemble components, looping through material or process changes if necessary. The output of this phase is the physical architecture (layout defined by component allocation and orientation and interfaces), the selected material and process subclass for each component, and the assembly strategy.

- The detailed design phase [23] aims to convert the components established during embodiment design into precise, production-ready specifications. Material and process selections continue to follow the previously outlined methodology, while Design for Excellence (DfX) principles [32] are applied to suit the chosen process and material members. It involves the specification of all product parts, including geometries, tolerances, materials, and PVs [19,20,27,28]. It concludes with the preparation of the complete technical documentation. Additionally, components may be subdivided into parts, or new parts can be introduced to accommodate assembly requirements; for instance, separate fasteners (e.g., screws or clips) or subassemblies may be specified to ensure correct fit, ease of assembly or manufacture, and reliable function in the final product. Additionally, low-level DCs guide geometry optimization, while PVs support the setup of manufacturing conditions to achieve the desired product requirements and define the material member (e.g., the specific supplier-grade material) and the process member (e.g., the exact machine or tooling used for production).

2.2. Reversing the Design Process to Enable DfMMAM

- •

- LPI-1 (variant design, part level). The product is redesigned for MMAM while keeping the physical and functional architecture and the material subclasses unchanged; only part geometry and process variables vary. This corresponds to CA in Yang et al. [21] and is consistent with Sossou et al.’s use of CA-type adaptations when architecture is preserved.

- •

- LPI-2 (adaptive design, assembly level). Design freedom increases to permit alternative assembly strategies via embodiment changes or component consolidation, and to allow modification of the material subclass, while the functional architecture and the locations and orientations of functions and DPs remain fixed. This aligns with RA in Yang et al. [21] and with Sossou et al.’s [10] architecture-minimization procedures under process-aware constraints.

- •

- LPI-3 (adaptive design, function level). Design freedom is highest: the functional architecture remains fixed, but function locations and orientations can be reassigned, enabling co-location of multiple functions within the same component volume and the use of hybrid-material solutions to reconcile conflicting requirements in a single bulk. This tier is conceptually compatible with the advanced integration capabilities discussed by Sossou et al. [10], and it extends beyond CA/RA by explicitly sanctioning function replacement and hybridization to achieve an integral, multifunctional product in one design space.

2.2.1. LPI-1: Variant Design—Part Level

2.2.2. LPI-2: Adaptive Design—Assembly Level

2.2.3. LPI-3: Adaptive Design—Function Level

3. Case Study: Trail Running Shoe Using Reverse-Traced Workflow

3.1. Design Based on Conventional Design Process

- •

- CR1: The shoe must prevent injuries from rocks, roots, and sharp objects.

- •

- CR2: The shoe must withstand rough usage.

- •

- CR3: The shoe must prevent ankle twisting or rolling.

- •

- CR4: The shoe should support the foot on uneven terrain.

- •

- CR5: The shoe should reduce the shock transferred to the foot to prevent fatigue.

- •

- CR6: The shoe shall distribute forces evenly to optimize user experience.

- •

- CRn…

3.2. Design Based on Reverse-Traced Workflow

| Design Phase | Detailed Design | Embodiment Design | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPI Level | LPI-1 | LPI-2 | LPI-3 |

| Constrain | Functional architecture Functional interfaces Component location and orientation Component assembly Material subclass | Functional architecture Functional interfaces Component location and orientation | Functional architecture |

| Freedom | Material member Part shape Parts assembly | Component assembly Material subclass | Functional Interfaces Component location and orientation Material family |

| Opportunity | Part consolidation Part geometry | Component consolidation | Function combination Hybrid material solution |

3.2.1. LPI-1: Trail Running Shoe—Part Level

3.2.2. LPI-2: Trail Running Shoe—Assembly Level

3.2.3. LPI-3: Trail Running Shoe—Function Level

- •

- Import mixture material (M.M.) defines the interaction of the shoe with the external environment, where the input flow is a mixture material (air, water, debris).

- •

- Extract gas material to solid/liquid/gas (S.L.G.M.), separate the gas material (air) from the mixture to enable the ventilation of the foot, and then Export gas material (G.M.) to the breathable air and moisture vapor out of the shoe within the function Inhibit solid/liquid material (S.L.M.) that blocks the ingress of mud and water.

- •

- The interfaces with the user are defined by Import Human Material (H.M.) for the foot entering the shoe and Import Human Energy (H.E.) to provide tension to the lacing system and import tactile status signal (Tac. S.) for the user feedback via lacing pressure, Convert (H.E. into M.E.) to convert the human force into tensile force at the foot–shoe interface, and Secure (H.M.) to wrap the foot inside the shoe system.

- •

- Another interface with the user is defined by Import Human Energy (H.E.) to provide motion to the foot and the interaction with the environment (also impact with external forces), Convert (H.E. into M.E.) to convert the human force into mechanical force, and Transmit (M.E.) mechanical energy through the sole and outer.

- •

- Then, Inhibit mechanical energy (Inhibit M.E.) arrests high-impact forces between the foot and the environment, Shape (M.E.) mechanical energy absorbs impact energy during the foot strike, Collect (M.E.) mechanical energy stores elastic energy, and finally, Transmit (M.E.) mechanical energy provides rebound force returned to the ground for propulsion.

- Dominant-Flow Heuristic: Air-Material Management Module: The four functions—Import M.M., Extract G.M. to S.L.M., Export M.M., and Inhibit S.L.M.—operate on a continuous, unbroken air-mixture material flow path. This path flows through breathability zones, through the waterproof membrane, and then vents out backward, with liquid blocking at each stage. The flow does not branch until the gas and solid/liquid mixture are fully separated. Because these four tertiary functions share one uninterrupted flow from entry to internal separation, they consolidate into a single Air-Material Management Module. By clustering these functions, the design achieves a cohesive module responsible for both ventilation and waterproofing.

- Conversion-Transmission Heuristic: User Interaction and Transmission Module: Convert H.E. to M.E. (Rigid Heel Counter) converts user force into mechanical force, which is immediately transmitted via Transmit M.E. (Shank Plate). These sequential conversion-transmission functions have no branching between them; conversion flows directly into transmission. The modular heuristic groups them into a single Energy Conversion and Transmission Module, where force is converted at the heel and transmitted through the midfoot in one physical assembly.

- Branching-Flow Heuristic: Energy Modules: After primary mechanical energy transmission, the functional flow diverges into three parallel branches, establishing natural module boundaries: Protection, Energy Attenuation, Storage, and Return Module.

- •

- Inhibit (S.L.M.) imposes a barrier to prevent solid and liquid material (mud, water) from entering the shoe interior.

- •

- Inhibit (M.E.) imposes a zero-velocity boundary to arrest peak mechanical loads at the toe and lateral surfaces.

- •

- Shape M.E. attenuates and absorbs impact energy.

- •

- Collect M.E. and Transmit M.E. capture, store, and return elastic energy for propulsion.

- •

- Air Management and Protection module: Combines material-flow functions with mechanical protection

- •

- Energy Conversion and Transmission module: Combines force input conversion with transmission, structural support and torsional control.

- •

- User Interaction module: Combines user fitting, setting, and foot retention functions.

- •

- Energy Attenuation, Storage, and Return module: Integrates multiple Shape/Collect/Transmit M.E. functions through spatial zoning.

4. Discussion

- •

- LPI-1 (variant design): Consolidation occurs only within parts belonging to the same component, with functional and physical architecture unchanged. Since parts from the same component already share DPs, maintaining FR independence by design, physical consolidation introduces no new coupling.

- •

- LPI-2 (adaptive design): Component consolidation uses three assembly approaches (consolidated, embedded, and regular assembly), with function allocation and locations remaining fixed to preserve functional decomposition. FR independence is verified through interface-led assessment, ensuring one component’s DP tuning does not force another.

- •

- LPI-3 (adaptive design): Functions co-locate within unified volumes via spatial zoning, with each zone assigned dedicated DPs tuned independently. Spatial zoning ensures functional independence despite physical co-location through material property boundaries that minimize problematic cross-coupling.

- •

- The primary criterion, preservation of FR independence as established by Axiomatic Design, is broadly generalizable across all LPI levels and industries.

- •

- Secondary criteria such as geometric adjacency, material compatibility, process feasibility, and DfX considerations have context-dependent weighting; their implementation strategies and relative weighting are product- and industry-specific.

- •

- Conceptual design deliberately avoids combining FRs to preserve design freedom and innovation space, ensuring that all solutions remain open before commitment to specific working principles.

- •

- Embodiment design first applies LPI-3, using function-sharing analysis to identify opportunities for grouping similar FRs within single DPs and function combinations to combine functions into modules, allowing the creation of hybrid material solutions. For LPI-3, this involves defining spatial zones and assigning distinct FRs to distinct zones within a unified component volume. Then, LPI-2 addresses assembly strategy (consolidated, embedded, and regular assembly) that best matches the product’s performance and manufacturability requirements. The consolidation strategy chosen at embodiment design directly shapes downstream detailed design activities.

- •

- Detailed design optimizes the geometry under PV constraints, enabling fully integrated parts where multiple FRs are fulfilled by independently controlled DPs. At detailed design, component consolidation is not revisited; the consolidation strategy is locked from the embodiment phase. Instead, detailed design focuses on geometry optimization within consolidated part boundaries; mesostructural design (lattice topology, material gradients, density profiles) supporting zone-specific DPs; and manufacturing process parameter selection, with voxel/layer-level control of material composition and deposition sequence to maintain zone-specific DP independence, ensuring the consolidation strategy is feasible.

- •

- LPI-1 for fast, low-risk updates that only tune geometry or process variables; it offers minimal cost and the fastest iteration, but limited integration potential with small part count reduction, no architectural change, and the lowest redesign/verification cost.

- •

- LPI-2, when the goal is assembly/interface reduction with fixed function locations, it provides meaningful BoM/interface reduction with moderate validation overhead, redesign effort, and potential serviceability constraints.

- •

- LPI-3 when architectural simplification requires co-locating functions via spatial zoning while keeping the functional decomposition fixed, balancing consolidation benefit against redesign and validation effort. LPI-3 maximizes integration/performance gains and part count reduction but requires the highest redesign/validation rigor and stricter independence control through zoned DPs/DCs.

- •

- LPI-1 aligns with redesigns that swap PVs and geometry while keeping architecture fixed. Porsche Design 3D MTRX II [48] exemplifies this approach, adjusting cushioning profiles through lattice topology tuning without modifying the fundamental upper/midsole/outsole structure or their distinct functional roles. This level represents the fastest, lowest-risk consolidation path, ideal for performance optimization within existing component boundaries.

- •

- LPI-2 corresponds to component consolidation into fewer parts with fixed function allocation and locations. Conformal lattice midsoles exemplify this by integrating impact absorption and energy return within a single consolidated component while preserving the upper and outsole as separate functional modules. Adidas 4DFWD [49] demonstrates this approach across product versions, consolidating cushioning and energy return elements while maintaining architectural clarity. Sintratec’s Cryptide sneaker [50] extends LPI-2 principles further, using laser sintering with flexible TPE to merge multiple footwear elements into one continuous part, proving viable assembly reduction without functional requirement reassignment. This level balances meaningful part-count and assembly cost savings against moderate verification complexity.

- •

- LPI-3 reflects function-level integration in a single design space with spatial zoning and co-location of distinct FRs. Fully printed footwear exemplifies this paradigm by merging upper, midsole, and outsole layers while embedding internal structures, all within one consolidated component. Zellerfeld’s fully 3D-printed Nike Air Max 1000 [51] merges upper and lower layers while embedding an internal air-cushioning structure, demonstrating sophisticated spatial integration. Neri Oxman’s “O0” shoe [52] represents an advanced vision for fully integrated, sustainable design made entirely from polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). This mono-material multifunctional component uses material gradients and spatial zoning to achieve structural support, cushioning, and environmental protection with distinct zone-specific DPs, all without assembly or adhesives. This level unlocks maximum consolidation but demands the highest verification rigor.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMAM | Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| RQ | Research Question |

| CA | Consistent Assembly |

| RA | Reduced Assembly |

| FR | Functional Requirement |

| NFR | Non-Functional Requirement |

| CR | Customer Requirement |

| DP | Design Parameter |

| DC | Design Criteria |

| PV | Process Variable |

| DfX | Design for Excellence |

| DfA | Design for Assembly |

| DfM | Design for Manufacturing |

| DfMMAM | Design for Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing |

Glossary

| Branching-flow Heuristic | A modular design rule suggesting that module boundaries should be placed at points where material, energy, or signal flows diverge (split) or converge [45]. |

| CA | Consistent Assembly. A design approach where the original assembly structure and part count are preserved, focusing on making the existing assembly manufacturable [21]. |

| Component | A distinct physical unit within a product that performs specific functions. In this framework, a component may consist of a single part or multiple parts. |

| Consolidation | The process of merging multiple discrete items into one, eliminating assembly interfaces [11,16,21,33]. |

| Conversion-transmission Heuristic | A modular design rule suggesting that a function converting a flow (e.g., electrical to mechanical) should be grouped with the subsequent transmission function [45]. |

| CRs | Customer Requirements. The initial set of needs and expectations gathered from the “Voice of the Customer” and stakeholders [19,20]. |

| DCs | Design Criteria. Measurable, quantitative specifications derived from NFRs used to evaluate design solutions [25]. |

| DfA | Design for Assembly. A methodology focusing on reducing product assembly cost and complexity, primarily by minimizing part count and simplifying assembly operations [12]. |

| DfM | Design for Manufacturing. A methodology focusing on minimizing the cost and complexity of manufacturing individual parts (e.g., maximizing ease of fabrication) [12]. |

| DfMMAM | Design for Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing. Design guidelines specifically tailored to exploit the capabilities of MMAM technologies [6,33]. |

| DfX | Design for Excellence. A systematic approach to product development that considers the full product lifecycle (manufacturing, assembly, service, etc.) [46]. |

| Dominant-flow Heuristic | A modular design rule suggesting that a chain of functions sharing a single, continuous flow should be grouped into the same module [45]. |

| DPs | Design Parameters. The key physical variables or solution elements in the physical domain chosen to satisfy the specified FRs [19,20]. |

| FGMs | Functionally Graded Materials. Materials characterized by gradual variation in composition and structure over volume, resulting in corresponding changes in properties [61,62,63,64]. |

| Flow | The material, energy, or signal that is exchanged or transformed between functions (e.g., electricity, mechanical force, data) [30]. |

| FRs | Functional Requirements. A minimum set of independent requirements that characterize the functional needs of the product (what the product must do) [25]. |

| Function | An abstract formulation of a task, independent of any specific solution, defined as the transformation of inputs (flows) into outputs. In the Functional Basis, it is typically expressed as an active verb (the function) acting on a flow (the object) [25,30]. |

| Function Combination | The integration of distinct functions (with different requirements) into a single component volume. MMAM enables this by spatially distributing different material properties (allocating distinct DPs) within a unified part, preserving functional independence. |

| Function Sharing | The consolidation of similar functions (handling similar flows) into a single DP. This strategy eliminates functional redundancy by satisfying multiple overlapping requirements with a single physical feature. |

| Functional Basis | A standardized design language (ontology) is used to describe product functions and flows (material, energy, signal) in a uniform manner [30]. |

| LPI | Level of Process Integration. A framework introduced in this work is to classify redesign scopes into three levels based on design novelty. |

| MMAM | Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing. Additive manufacturing processes capable of depositing or fusing different materials within a single build [1,6,35]. |

| Module | A physical unit composed of one or more functions that facilitate specific interactions; often the result of consolidation in LPI-3 [45,46,65]. |

| NFRs | Non-Functional Requirements. Constraints on the design (e.g., cost, weight, reliability) describe how well the product must perform its functions, often determining the quality of the solution [25]. |

| Part | The lowest level of physical hierarchy; an elementary piece that cannot be disassembled further without destruction. |

| Physical Principle | Or called Working Principles, is the physical effect (e.g., friction, leverage, thermal expansion) selected to realize a specific function. The combination of several working principles results in the working structure of a solution. [23] |

| PVs | Process Variables. The key variables in the process domain (manufacturing settings and material properties) that characterize the process used to generate the specified DPs [19,20]. |

| RA | Reduced Assembly. A design approach focusing on reducing part count through consolidation and function integration [21]. |

| Tertiary Functions | Tertiary functions are the third level of the functional hierarchy in the Functional Basis, which provide more specific function definitions than the class (primary) or secondary levels, leading to specific technologies or physical principles [30]. |

References

- Hasanov, S.; Alkunte, S.; Rajeshirke, M.; Gupta, A.; Huseynov, O.; Fidan, I.; Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Rennie, A. Review on Additive Manufacturing of Multi-Material Parts: Progress and Challenges. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, G.H.; Pei, E.; Harrison, D.; Monzón, M.D. An Overview of Functionally Graded Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 23, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Burggraeve, S.; Lietaert, P.; Stroobants, J.; Xie, X.; Jonckheere, S.; Pluymers, B.; Desmet, W. Model-Based, Multi-Material Topology Optimization Taking into Account Cost and Manufacturability. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2020, 62, 2951–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Griffis, J.; Manogharan, G.; Panesar, A. Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: A Computational Design Perspective. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2546671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Lee, H. Recent Advances in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Methods and Applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Gokcekaya, O.; Md Masum Billah, K.; Ertugrul, O.; Jiang, J.; Sun, J.; Hussain, S. Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: A Systematic Review of Design, Properties, Applications, Challenges, and 3D Printing of Materials and Cellular Metamaterials. Mater. Des. 2023, 226, 111661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.; Mognol, P.; Hascoet, J.-Y. Functionally Graded Material (FGM) Parts: From Design to the Manufacturing Simulation. In Proceedings of the Engineering Systems Design and Analysis; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 44878, pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, B.; Anderson, D.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Wood, K.L. Crowdsourced Design Principles for Leveraging the Capabilities of Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 15), Milan, Italy, 27 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Calius, E.; Huang, L.; Singamneni, S. Artificial Evolution and Design for Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 7, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossou, G.; Demoly, F.; Gomes, S.; Montavon, G. An Assembly-Oriented Design Framework for Additive Manufacturing. Designs 2022, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sossou, G.; Demoly, F.; Montavon, G.; Gomes, S. An Additive Manufacturing Oriented Design Approach to Mechanical Assemblies. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2018, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formentini, G.; Boix Rodríguez, N.; Favi, C. Design for Manufacturing and Assembly Methods in the Product Development Process of Mechanical Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 4307–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargnier, H.; Kromm, F.X.; Danis, M.; Brechet, Y. Proposal for a Multi-Material Design Procedure. Mater. Des. 2014, 56, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Moon, S.K.; Bi, G.; Wei, J. A Multi-Material Part Design Framework in Additive Manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 99, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watschke, H.; Kuschmitz, S.; Heubach, J.; Lehne, G.; Vietor, T. A Methodical Approach to Support Conceptual Design for Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design, ICED 2019, Delft, The Netherlands, 5–8 August 2019; pp. 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.F. A New Part Consolidation Method to Embrace the Design Freedom of Additive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2015, 20, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, T.; Gu, P.; Jin, Y.; Lutters, D.; Kind, C.; Kimura, F. Design Methodologies: Industrial and Educational Applications. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 58, 543–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkamp, T.; Hilbig, K.; Girnth, S.; Kuschmitz, S.; Waldt, N.; Klawitter, G.; Vietor, T. Adapted Design Process for Continuous Fiber-Reinforced Additive Manufacturing—A Methodological Framework. Materials 2024, 17, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebala, D.A.; Suh, P. An Application of Axiomatic Design. Res. Eng. Des. 1992, 3, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, N.P. Designing-in of Quality Through Axiomatic Design. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1995, 25, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.F. Assembly-Level Design for Additive Manufacturing: Issues and Benchmark. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Charlotte, NC, USA, 21–24 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, Y.F. Conceptual Design for Assembly in the Context of Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium—An Additive Manufacturing Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 8–10 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl, G.; Beitz, W. Engineering Design: A Systematic Approach, 3rd ed.; Wallace, K., Blessing, L., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781846283185. [Google Scholar]

- Gericke, K.; Blessing, L. An Analysis of Design Process Models Across Disciplines. In Proceedings of the International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, S. The Systems Engineering Tool Box—Holistic Requirements Model (HRM). 2006. Available online: https://www.burgehugheswalsh.co.uk/Uploaded/1/Documents/Holistic-Requirements-Model-Tool-v2.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA. NASA Systems Engineering Handbook (SP-2016-6105) Rev 2; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 3016210134. [Google Scholar]

- Salonitis, K. Design for Additive Manufacturing Based on the Axiomatic Design Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 87, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puik, E.; Lafeber, R. Mathematical Approach of High-Tech Systems Design—Axiomatic Design. Mikroniek 2023, 3, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, S. The Systems Engineering Tool Box—Functional Modelling. 2011. Available online: https://www.burgehugheswalsh.co.uk/Uploaded/1/Documents/Functional-Modelling-Tool-Draft-2.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Hirtz, J.; Stone, R.B.; McAdams, D.A.; Szykman, S.; Wood, K.L. A Functional Basis for Engineering Design: Reconciling and Evolving Previous Efforts. Res. Eng. Des.—Theory Appl. Concurr. Eng. 2002, 13, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Ullman The Mechanical Design Process; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2008.

- Chiu, M.C.; Kremer, G.E.O. Investigation of the Applicability of Design for X Tools during Design Concept Evolution: A Literature Review. Int. J. Prod. Dev. 2011, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B.; Khorasani, M. Design for Additive Manufacturing. In Additive Manufacturing Technologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 555–607. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby, M. Materials Selection in Mechanical Design, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 9780080952, ISBN 9780080952239. [Google Scholar]

- Nipu, S.M.A.; Tang, T.; Joralmon, D.; Liu, T.; Li, R.; Yoo, M.; Li, X. Advances and Perspectives in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing of Heterogenous Metal-Polymer Components. npj Adv. Manuf. 2025, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargnier, H.; Castillo, G.; Danis, M.; Brechet, Y. Study of the Compatibility between Criteria in a Set of Materials Requirements: Application to a Machine Tool Frame. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, A.T.; Woizeschke, P.; Rankouhi, B.; Pfefferkorn, F.E.; Bartels, D.; Schmidt, M.; Wits, W.W. Metal Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing: Overcoming Barriers to Implementation. CIRP Ann. 2025, 74, 869–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, N.; Fu, Z.; Niu, B.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Mei, D.; Li, Q.; Song, B.; He, J. Additive Manufacturing of Immiscible Alloys: Breaking the Preparation Bottleneck and Unlocking the Property Potential. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1027, 180544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakirov, S. Is Compatibility Critical in Polymer Engineering? Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2024, 7, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, T.; Su, R.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.C.L. ITIL: Interlaced Topologically Interlocking Lattice for Continuous Dual-Material Extrusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüzün, G.J.; Roth, D.; Kreimeyer, M. Function Integration in Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Approaches. In Proceedings of the Design Society; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 2005–2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, K.T.; Seering, W.P. Function Sharing in Mechanical Design. In Proceedings of the AAAI-88 Proceedings; AAAI: Washington, DC, USA, 1988; pp. 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams, D.A.; Stone, R.B.; Wood, K.L. Functional Interdependence and Product Similarity Based on Customer Needs. Res. Eng. Des. 1999, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, A.; Dong, A.; Goucher-Lambert, K. Evaluating Quantitative Measures for Assessing Functional Similarity in Engineering Design. J. Mech. Des. 2022, 144, 031401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, K.; Wood, K. Product Design: Techniques in Reverse Engineering and New Product Development; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-13-021271-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, K.T.; Eppinger, S.D. Product Design and Development; McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780078029066. [Google Scholar]

- 3MF Consortium. Available online: https://3mf.io/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Porsche Design 3D MTRX II. Available online: https://shop.porsche.com/it/it-IT/p/3d-mtrx-ii-sneaker-P-P5740-62/4056487067896 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Adidas 4dfwd. Available online: https://www.carbon3d.com/resources/case-study/introducing-adidas-4dfwd-the-worlds-first-3d-printed-anisotropic-lattice-midsole-designed-to-move-you-forward (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Cryptide Sneaker. Available online: https://3dprintingindustry.com/news/german-designer-unveils-customizable-creature-like-3d-printed-cryptide-sneaker-204957/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Zellerfeld—3D Printed Shoes. Available online: https://www.zellerfeld.com (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Oxman-Projects O0. Available online: https://oxman.com/projects/o0 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Dal Fabbro, P.; Maltauro, M.; Grigolato, L.; Rosso, S.; Meneghello, R.; Concheri, G.; Savio, G. Representative Volume Element Analysis in Material Coextrusion. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Kalamkarov, A.L.; Andrianov, I.V.; Danishevs’kyy, V.V. Asymptotic Homogenization of Composite Materials and Structures. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2009, 62, 030802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, G.; Curtarello, A.; Rosso, S.; Meneghello, R.; Concheri, G. Homogenization Driven Design of Lightweight Structures for Additive Manufacturing. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptochos, E.; Labeas, G. Elastic Modulus and Poisson’s Ratio Determination of Micro-Lattice Cellular Structures by Analytical, Numerical and Homogenisation Methods. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 2012, 14, 597–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.F. A 149 Line Homogenization Code for Three-Dimensional Cellular Materials Written in MATLAB. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. Trans. ASME 2019, 141, 011005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, S.; Gupta, A.; Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Fidan, I. Hierarchical Homogenization and Experimental Evaluation of Functionally Graded Materials Manufactured by the Fused Filament Fabrication Process. Compos. Struct. 2021, 275, 114488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonabadi, H.; Chen, Y.; Yadav, A.; Bull, S. Investigation of the Effect of Raster Angle, Build Orientation, and Infill Density on the Elastic Response of 3D Printed Parts Using Finite Element Microstructural Modeling and Homogenization Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 1485–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigolato, L.; Savio, G. Development of Functionally Graded Properties Components via Filament Foaming in Material Extrusion. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggarapu, V.; Gujjala, R.; Ojha, S.; Acharya, S.; Venkateswara babu, P.; Chowdary, S.; kumar Gara, D. State of the Art in Functionally Graded Materials. Compos. Struct. 2021, 262, 113596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jaiswal, P.; Rai, R.; Nelaturi, S. Additive Manufacturing of Functionally Graded Material Objects: A Review. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2018, 18, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Z.; Hao, L.; Huang, L.; Xin, C.; Wang, Y.; Bilotti, E.; Essa, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; et al. A Review on Functionally Graded Materials and Structures via Additive Manufacturing: From Multi-Scale Design to Versatile Functional Properties. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 1900981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Galy, I.M.; Saleh, B.I.; Ahmed, M.H. Functionally Graded Materials Classifications and Development Trends from Industrial Point of View. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, F. Approaches to Modularity in Product Architecture; Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| AM Unique Capabilities | Opportunities | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Shape Complexity | Tailored geometry to different contexts and at different scales. | Part consolidation and embodiment for a reduced BoM. Custom-designed geometries. Tailored mesostructures and part-scale macrostructures. |

| Material Complexity | Tailored material composition. | A hybrid material that satisfies multiple conflicting requirements. FGM to tailor the transition and enable the combination of incompatible materials. Tailored nano-/microstructures. |

| Functional Complexity | Tailored functions allocations. | Functions sharing and combinations. More functions are associated with the same component. |

| Components | Material Subclass | Shaping Process Subclass | Joining Process Subclass |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breathability Zones | Polyamide mesh | Cutting | Lamination |

| Waterproof Membrane | Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene membrane | Cutting | Lamination |

| Protective Overlays | Thermoplastic polyurethane | Injection molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Outer | Polyamide mesh | Cutting | Adhesive Dispensing, Sewing |

| Toe Cap | Thermoplastic polyurethane | Thermoforming | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Side Reinforcements | Thermoplastic polyurethane | Cutting | Polymer welding |

| Laces | Polyamide | Braiding | Eyelet |

| Tongue | Polyamide mesh | Cutting | Sewing |

| Collar | Polyamide mesh | Cutting | Sewing |

| Flexible Upper Parts | Thermoplastic polyurethane | Cutting | Sewing |

| Cushioning (liner) | Polyurethane | Cutting | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Rigid Heel Counter | Thermoplastic polyurethane | Injection molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Shank Plate | Glass fiber-reinforced polymer | Compression molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Heel Crash Pad | Ethylene-vinyl acetate | Compression molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Insole | Ethylene-vinyl acetate | Cutting | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Midsole | Ethylene-vinyl acetate | Compression molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Medial Post | Ethylene-vinyl acetate | Compression molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Energy-Return Pods | Thermoplastic polyurethane | Injection molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Outsole | Styrene-butadiene rubber | Compression molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Multi-Zone Tread Lugs | Styrene-butadiene rubber | Compression molding | Adhesive Dispensing |

| Components | Functions Lev. 3 | DPs Lev. 3 | DCs Lev. 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breathability Zones | Import M.M. (admit air) Inhibit S.L.M. (block splash) Export G.M. (export air) | Mesh opening architecture (grid spacing) | Airflow passage capacity ≥ 2 cm3/(s·cm2) |

| Waterproof Membrane | Extract G.M. to S.L.M. (block liquid, pass vapor) | Membrane channel structure (passage width) | Channel passage allows vapor transmission ≥ 1000 g/(m2·24 h) |

| Protective Overlays | Inhibit M.E. (external protection) | Overlay coverage pattern (spatial area distribution) | Tear strength ≥ 45 N Abrasion ≥ 10,000 cycles |

| Outer | Inhibit S.L.M. (coverage) | Outer shell structure (coverage pattern and surface integrity profile) | Coverage area ≥ 95% of dorsal surface, Abrasion ≥ 10,000 cycles |

| Toe Cap | Inhibit M.E. (protect toes) | Shell dome structure (radial wall curvature) | Deflection angle ≤ 15°, Abrasion ≥ 10,000 cycles, Impact resist ≥ 50 J |

| Side Reinforcements | Inhibit M.E. (lateral bracing) | Geometric profile and thickness distribution | Lateral displacement ≤ 5 mm in dynamic motion Abrasion ≥ 10,000 cycles |

| Laces | Import H.M. (enable closure) | Spacing architecture and sizing topology | Eyelet spacing supports easy lacing/unlacing |

| Tongue | Import Tac. S. (buffer laces) | Slot distribution pattern and buffer topology | Tongue pressure ≤ 75 kPa under lacing, Abrasion ≥ 100,000 cycles |

| Collar | Secure H.M. (comfort hold) | Circumferential support profile and contact topology | Collar pressure ≤ 50 kPa around ankle, Abrasion ≥ 10,000 cycles |

| Flexible Upper Parts (vamp) | Secure H.M. (allow motion) | Dorsal-to-ventral profile and opening topology | Flex zones support ≥ 30° dorsiflexion, Flex cycles and Abrasion ≥ 100,000. |

| Cushioning (liner) | Shape M.E. (offload laterals) | Cushion layer thickness distribution (thickness profile across surface) | Peak pressure ≤ 150 kPa on lateral surfaces, compression set ≤ 8% after 100,000 cycles |

| Rigid Heel Counter | Convert H.E.to M.E. (stabilize heel) | Cushion layer thickness distribution (thickness profile across surface) | Flex-zone position and thickness control ≤ 5 mm heel displacement at 50 N load |

| Shank Plate | Transmit M.E. (torsion control) | Shank plate cross-section profile and contact area. | Cross-section shape provides ≥ 15 Nm/degree torsional rigidity |

| Heel Crash Pad | Shape M.E. (attenuate heel impact) | Heel crash wedge shape (wedge angle and height profile) | Wedge profile achieves ≥ 50% energy absorption during impact |

| Insole | Shape M.E. (distribute load) | Insole contact area and arch structure (arch rise profile across length) | Peak plantar pressure ≤ 280 kPa during gait, compression set ≤ 8% after 100,000 cycles |

| Midsole | Shape M.E. (attenuate shock) | Midsole contour shape (curvature and thickness profile) | Energy absorption ≥ 50%, Abrasion ≥ 100,000 cycles, compression set ≤ 8% after 100 000 cycles, hardness 45 Asker C |

| Medial Post | Shape M.E. (limit pronation) | Medial post projection shape (projection depth and angle) | Medial stiffness ≥ 2 × lateral in rearfoot, Abrasion ≥ 10,000 cycles, compression set ≤ 8% after 100 000 cycles |

| Energy-Return Pods | Collect M.E. (store energy) | Energy pod cavity structure (cavity shape and spatial arrangement) | Energy return efficiency ≥ 60% |

| Outsole | Transmit M.E. (release energy to ground interface) | Outsole base plate geometry (thickness and surface profile) | Coefficient of friction ≥ 0.65 on wet surfaces, Abrasion ≥ 100,000 cycles hardness 70 Shore A |

| Multi-Zone Tread Lugs | Transmit M.E. (multi-direction grip) | Tread lug array structure (lug base shape, height, and spacing pattern) | Grip ≥ 0.7 coefficient in all directions, Abrasion ≥ 100,000 cycles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dal Fabbro, P.; Grigolato, L.; Savio, G. A Systematic Methodology for Design in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing Derived by a Reverse-Traced Workflow. Eng 2026, 7, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010013

Dal Fabbro P, Grigolato L, Savio G. A Systematic Methodology for Design in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing Derived by a Reverse-Traced Workflow. Eng. 2026; 7(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleDal Fabbro, Pierandrea, Luca Grigolato, and Gianpaolo Savio. 2026. "A Systematic Methodology for Design in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing Derived by a Reverse-Traced Workflow" Eng 7, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010013

APA StyleDal Fabbro, P., Grigolato, L., & Savio, G. (2026). A Systematic Methodology for Design in Multi-Material Additive Manufacturing Derived by a Reverse-Traced Workflow. Eng, 7(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010013