Residual Strength of Adhesively Bonded Joints Under High-Velocity Impact: Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Impact-Induced Degradation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Work

3. Numerical Modeling

4. Results and Discussion

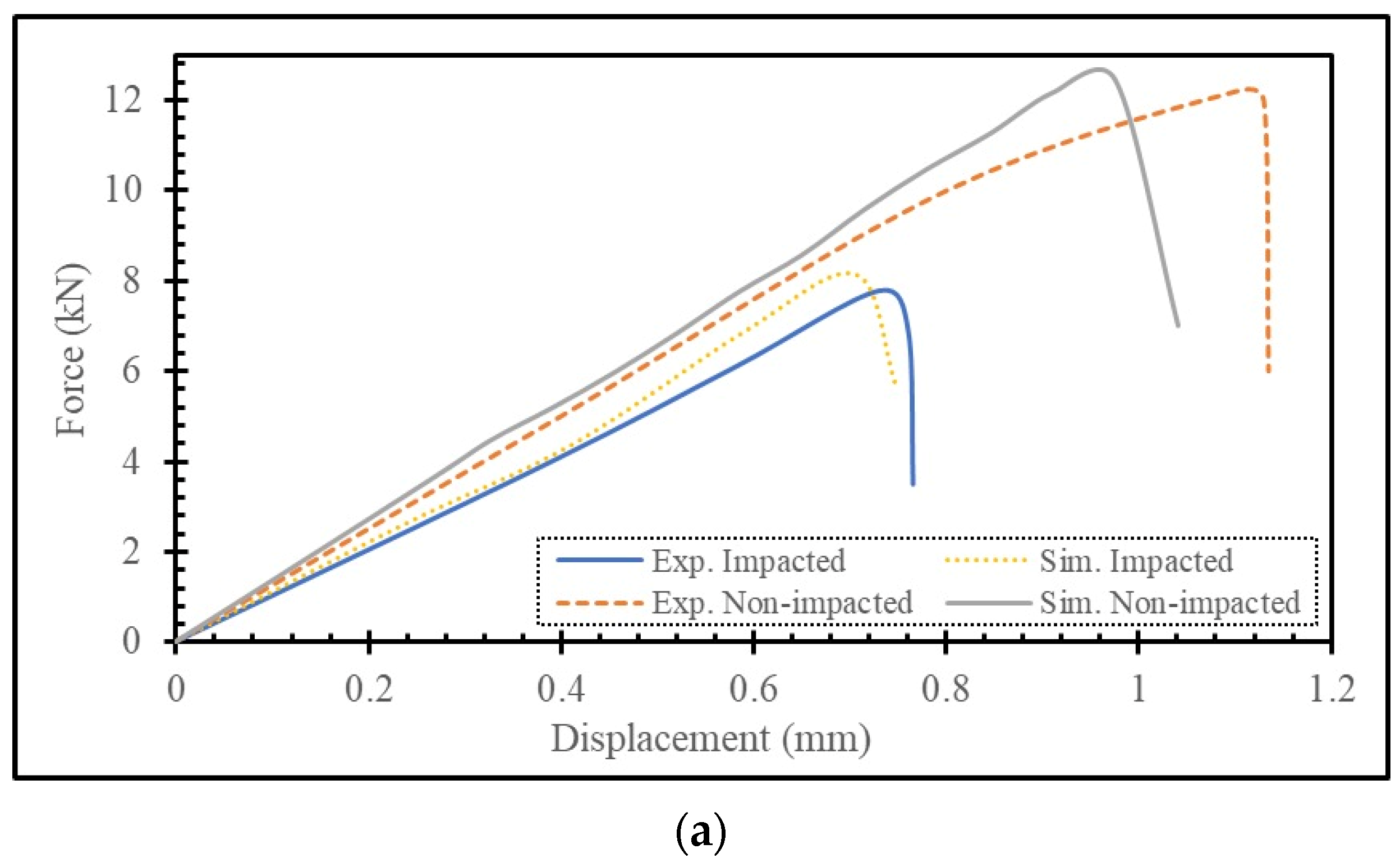

4.1. Calibration of the Material Constants

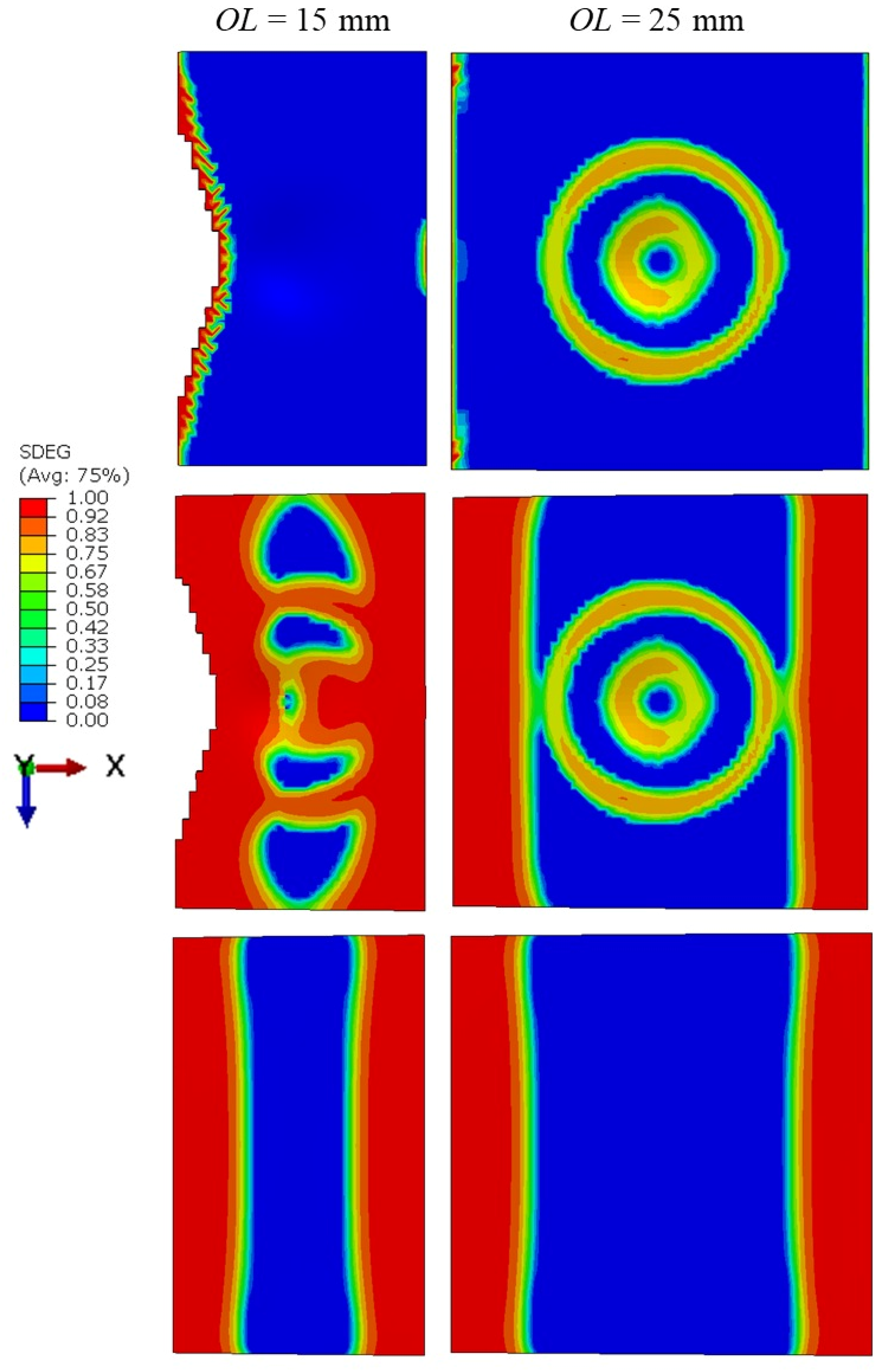

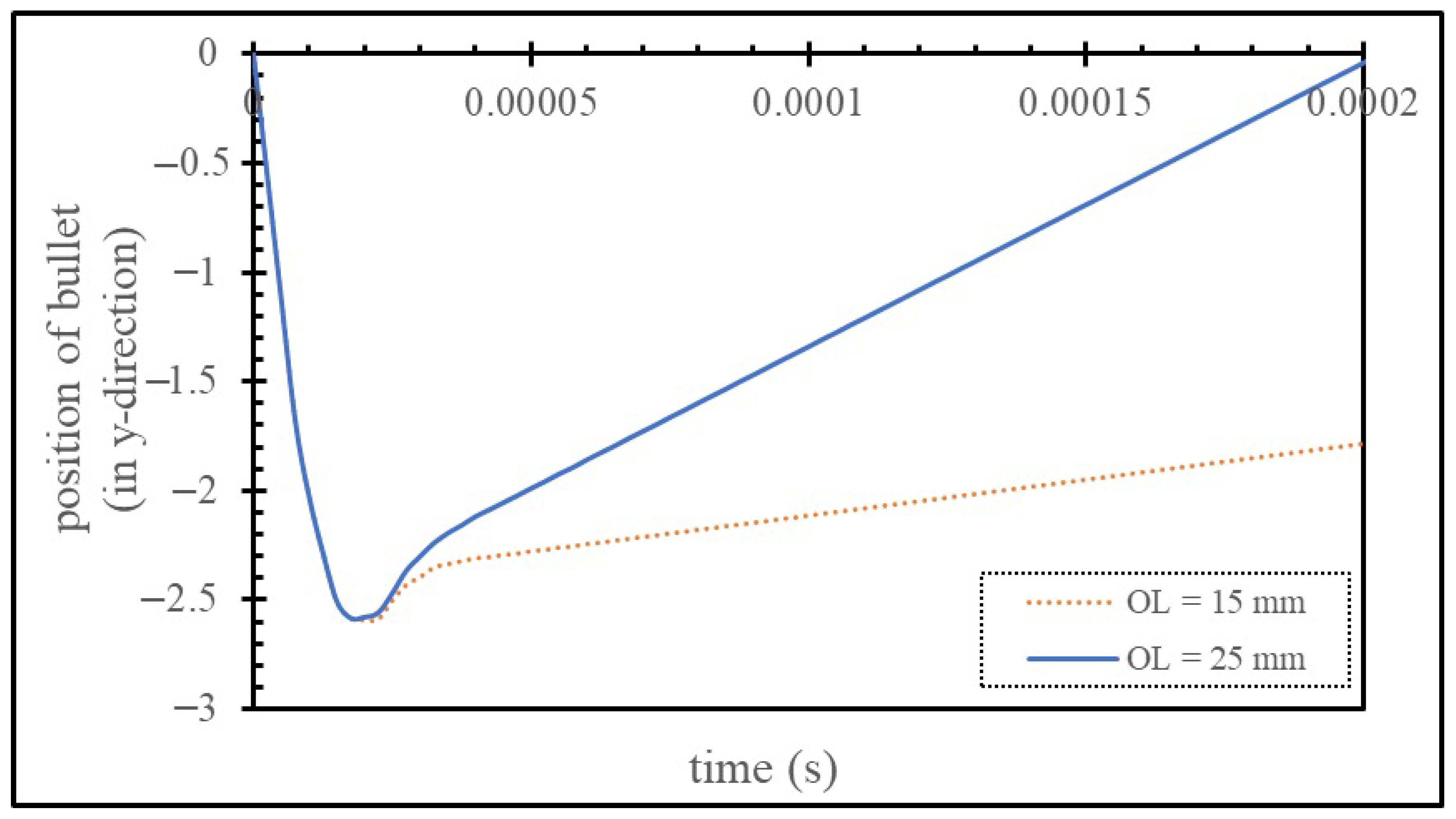

4.2. Influence of the Overlap Length

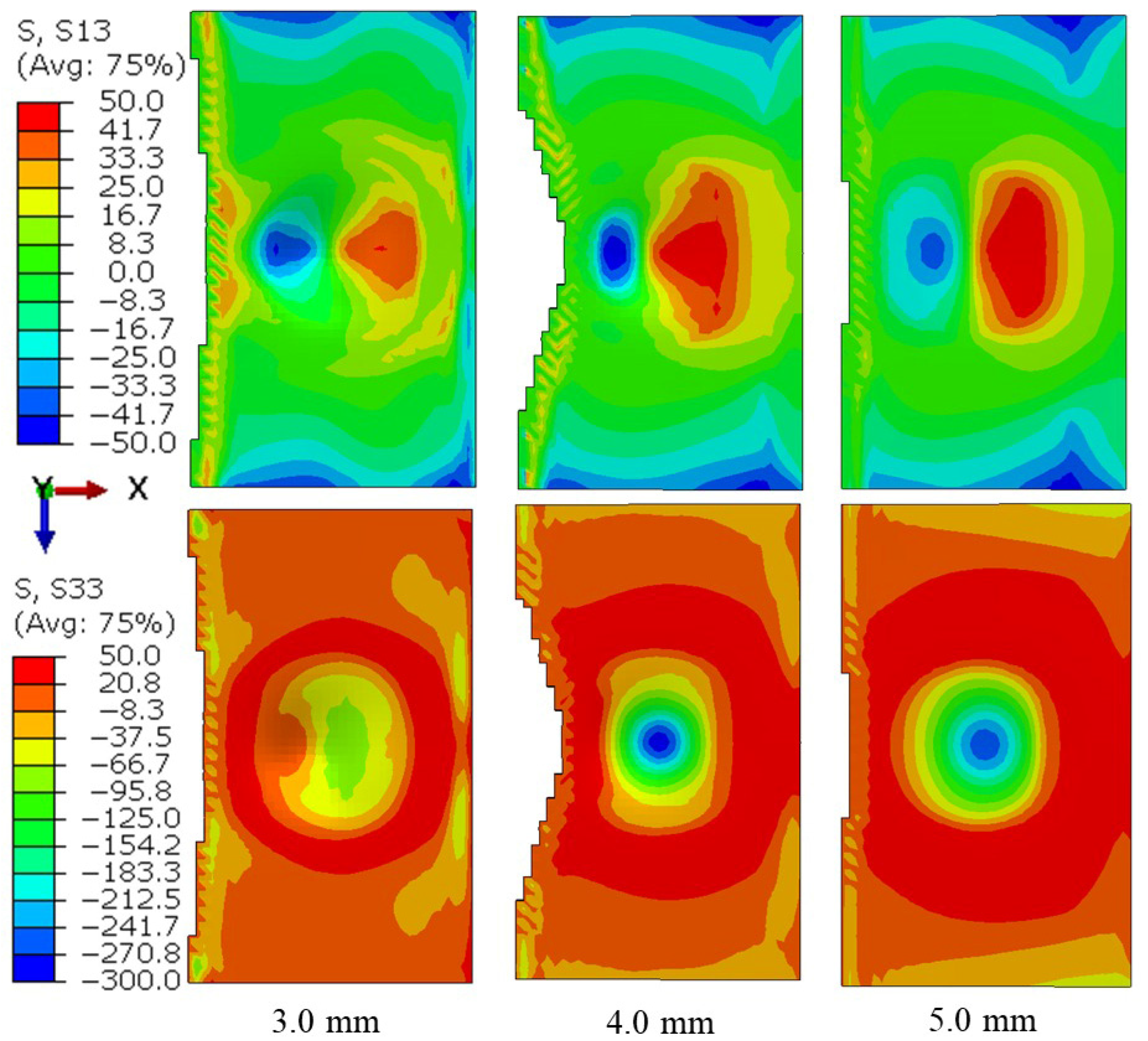

4.3. Influence of Adherend Thickness

5. Conclusions

- Experimental results indicated that the post-impact tensile strength of the 15 mm overlap configuration exhibited significant degradation, with the load-bearing capacity decreasing by approximately 33%, whereas the 25 mm overlap configuration largely maintained its post-impact structural integrity.

- The FE simulations demonstrated that the adhesive layer behaved about 5 times stronger under the imposed high-velocity impact loading than under the quasi-static one.

- The FE analysis of damage progression in the adhesive layer indicated that bullet impact caused damage at the ends for shorter overlap lengths, while for longer overlap lengths, damage was confined to the center. Since the ends of the overlap length bore more tensile loading compared to the central region, joints with an overlap length of 15 mm experienced mechanical degradation, whereas those with a 25 mm overlap length did not.

- Contrary to predictions, a larger stiffness mismatch between the adherends and the adhesive caused more damage to the adhesive layer when the adherend thickness was increased from 3.0 mm to 4.0 mm. However, by raising the thickness to 5.0 mm, more uniform deformation and less overall damage were achieved as the adhesive layer moved away from the impact surface, reducing the damaged area.

- The damaged pattern in the adhesive layer left from the pre-impact did not fully explain the reduction in Fmax from the tensile test for different adherend thicknesses. Despite having the lowest damaged area (0.84%) for t = 5.0 mm, this configuration showed the largest decrease in Fmax (50.08%) compared to non-impacted specimens due to the homogeneous distribution of higher stresses in the adhesive layer, leading to early damage onset during tensile testing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maggiore, S.; Banea, M.D.; Stagnaro, P.; Luciano, G. A review of structural adhesive joints in hybrid joining processes. Polymers 2021, 13, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, F.; Chiquito, M.; Castedo, R.; Yenes, J.I.; Almajano, S.M.; Lopez, L.M.; Santos, A.P. Experimental study on the energy absorption capacity of concrete masonry unit under ballistic impact. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goglio, L.; Rosetto, M. Impact rupture of structural adhesive joints under different stress combinations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2008, 35, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorek, A.; Godzimirski, J. Modified pendulum hammer in impact tests of adhesive, riveted and hybrid lap joints. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 104, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, F.; Adams, R.D. Flexible adhesives for automotive application under impact loading. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2015, 56, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuancheng, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Liao, Y. Experimental-numerical analysis of failure of adhesively bonded lap joints under transverse impact and different temperatures. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2020, 140, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J.P.A.; Campilho, R.D.S.G.; Marques, E.A.S.; Machado, J.J.M.; da Silva, L.F.M. Adhesive joint analysis under tensile impact loads by cohesive zone modelling. Compos. Struct. 2019, 222, 110894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.J.M.; Nunes, P.D.P.; Marques, E.A.S.; da Silva, L.F.M. Adhesive joints using aluminum and cfrp substrates tested at low and high temperatures under quasi-static and impact conditions for the automotive industry. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 158, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Nakai, K. Determination of the impact tensile strength of structural adhesive butt joints with a modified split hopkinson pressure bar. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2015, 56, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykhere, S.L.; Kumar, P.; Singh, R.K.; Parameswaran, V. Dynamic shear strength of adhesive joints made of metallic and composite adherents. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 2102–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, C.; Ikegami, K. Strength of adhesively-bonded butt joints of tubes subjected to combined high-rate loads. J. Adhes. 1999, 70, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollins, K.; Elvin, N.; Delale, F. Characterization of adhesive joints under high-speed normal impact: Part ii—Numerical studies. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliot, C.; Rousseau, J.; Verchery, G. Drop weight tensile impact testing of adhesively bonded carbon/epoxy laminate joints. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2012, 35, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, C.; Ikegami, K. Dynamic deformation of lap joints and scarf joints under impact loads. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2000, 20, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challita, G.; Othman, R.; Casari, P.; Khalil, K. Experimental investigation of the shear dynamic behaviour of double-lap adhesively bonded joints on a wide range of strain rates. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2011, 31, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, F. Mechanical behaviour of adhesively single lap joint under buckling conditions. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.D.; Peppiatt, N.A. Stress analysis of adhesive-bonded lap joints. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 1974, 9, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltannia, B.; Duke, K.; Taheri, F.; Mertiny, P. Quantification of the effects of strain rate and nano-reinforcement on the performance of adhesively bonded single-lap joints. Rev. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 8, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Z.G.; Lu, Y. Evaluation of typical concrete material models used in hydrocodes for high dynamic response simulations. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2009, 36, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Kuznetsov, V.; Waschl, J.; Hao, H. Numerical calculation of concrete slab response to blast loading. Trans. Tianjin Univ. (Engl. Ed.) 2006, 12, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Goglio, L.; Peroni, L.; Peroni, M.; Rossetto, M. High strain-rate compression and tension behaviour of an epoxy bi-component adhesive. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2008, 28, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S. Enhancing mechanical properties of GFRP–aluminum joints through Z pinning: A low velocity shear impact study. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 4391–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xuan, H.; Qin, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W. Numerical and experimental study of the residual strength of CFRP laminate single-lap joint after transverse impact. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 130, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.A.; Campilho, R.D.; Valente, J.P.; Queirós, M.J.; Madani, K. Impact loading analysis of double-lap composite bonded joints. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2024, 128, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, M.; Kadioglu, F. Residual strength and failure evolution of adhesively bonded joints under successive ballistic impacts. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 182, 110021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollins, K.; Elvin, N.; Delale, F. Characterization of Adhesive Joints under High-Speed Normal Impact: Part I—Experimental Studies. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABAQUS. Abaqus Unified FEA-3DEXPERIENCE; R2018; Dassault Systèmes: Vélizy-Villacoublay, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Demiral, M.; Abbassi, F.; Muhammad, R.; Akpinar, S. Service life modelling of single lap joint subjected to cyclic bending load. Aerospace 2022, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. A Constitutive Model and Data for Metal Subjected to Large Strains, High Strain Rates and High Temperature. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, Hague, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Oshima, S.; Koyanagi, J. Review on Damage and Failure in Adhesively Bonded Composite Joints: A Microscopic Aspect. Polymers 2025, 17, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, S.; Jaffery, S.H.I.; Khan, M.; Fahad, M.; Mubashar, A.; Ali, L. Numerical and experimental investigation of Johnson–Cook material models for aluminum (Al 6061-T6) alloy using orthogonal machining approach. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814018797794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Kukshal, V. Numerical analysis for estimating ballistic performance of armour material. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 4731–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, M.; Kadioglu, F.; Silberschmidt, V.V. Size effect in flexural behaviour of unidirectional GFRP composites. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2020, 34, 5053–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, F.; Demiral, M.; El Zaroug, M. Effects of overlap length on the strength of bolted, bonded and hybrid single lap joints with different adherend materials and thicknesses. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 2191–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, D.G.; Carbas, R.J.; Marques, C.E.A.S.; Da Silva, L.F.M. Reinforcement of CFRP joints with fibre metal laminates and additional adhesive layers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 165, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zaroug, M.; Kadioglu, F.; Demiral, M.; Saad, D. Experimental and numerical investigation into strength of bolted, bonded and hybrid single lap joints: Effects of adherend material type and thickness. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2018, 87, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, W.J.; Vinson, J.R. The efficient design of adhesive bonded joints. J. Adhes. 1975, 7, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goland, M.; Reisaner, E. The stresses in cemented joints. J. App. Mech. 1944, 11, A17–A27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart-Smith, L.J. Stress Analysis; a Continuum Mechanics Approach in Developments in Adhesives 2; Elsevier Applied Science Publishers: London, UK, 1981; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.D.; Comyn, J.; Wake, W.C. Structural Adhesive Joints in Engineering, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Applied Science Publishers: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, A.M.; Reis, P.N.B.; de Moura, M.; Santos, J.B. Influence of the specimen thickness on low velocity impact behavior of composites. J. Polym. Eng. 2012, 32, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | A (MPa) | B (MPa) | C | n | m | Tr (K) | Tm (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | 24 | 21 | 0.001 | 0.7 | 1 | 298 | 925 |

| Aluminum | 324 | 114 | 0.002 | 0.42 | 1.34 | 293 | 893 |

| Knn, Kss, Ktt (N/mm3) | (MPa) | = (MPa) | (N/mm) | = (N/mm) | |

| Model1-Quasi-static [35] | 100,000 | 46.93 | 46.86 | 4.05 | 9.77 |

| Model2—Dynamic | 240 | 240 |

| 3.0 mm | 4.0 mm | 5.0 mm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Impacted | 12.23 | 12.43 | 12.86 |

| Impacted | 10.07 | 8.14 | 6.42 |

| Reduction in Fmax (%) | 17.66 | 34.51 | 50.08 |

| Specimen | OL | Exp | FE | Difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Impacted | 15 | 12.2 ± 0.78 | 12.42 | 1.80 |

| Impacted | 15 | 7.81 ± 0.51 | 8.15 | 4.17 |

| Non-Impacted | 25 | 15.51 ± 0.91 | 14.63 | 5.67 |

| Impacted | 25 | 15.03 ± 0.97 | 15.17 | 0.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kadioglu, F.; Demiral, M.; Mamedov, A. Residual Strength of Adhesively Bonded Joints Under High-Velocity Impact: Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Impact-Induced Degradation. Eng 2026, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010001

Kadioglu F, Demiral M, Mamedov A. Residual Strength of Adhesively Bonded Joints Under High-Velocity Impact: Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Impact-Induced Degradation. Eng. 2026; 7(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleKadioglu, Ferhat, Murat Demiral, and Ali Mamedov. 2026. "Residual Strength of Adhesively Bonded Joints Under High-Velocity Impact: Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Impact-Induced Degradation" Eng 7, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010001

APA StyleKadioglu, F., Demiral, M., & Mamedov, A. (2026). Residual Strength of Adhesively Bonded Joints Under High-Velocity Impact: Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Impact-Induced Degradation. Eng, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng7010001