A Machine Learning-Optimized Robot-Assisted Driving System for Efficient Flexible Forming of Composite Curved Components

Abstract

1. Introduction

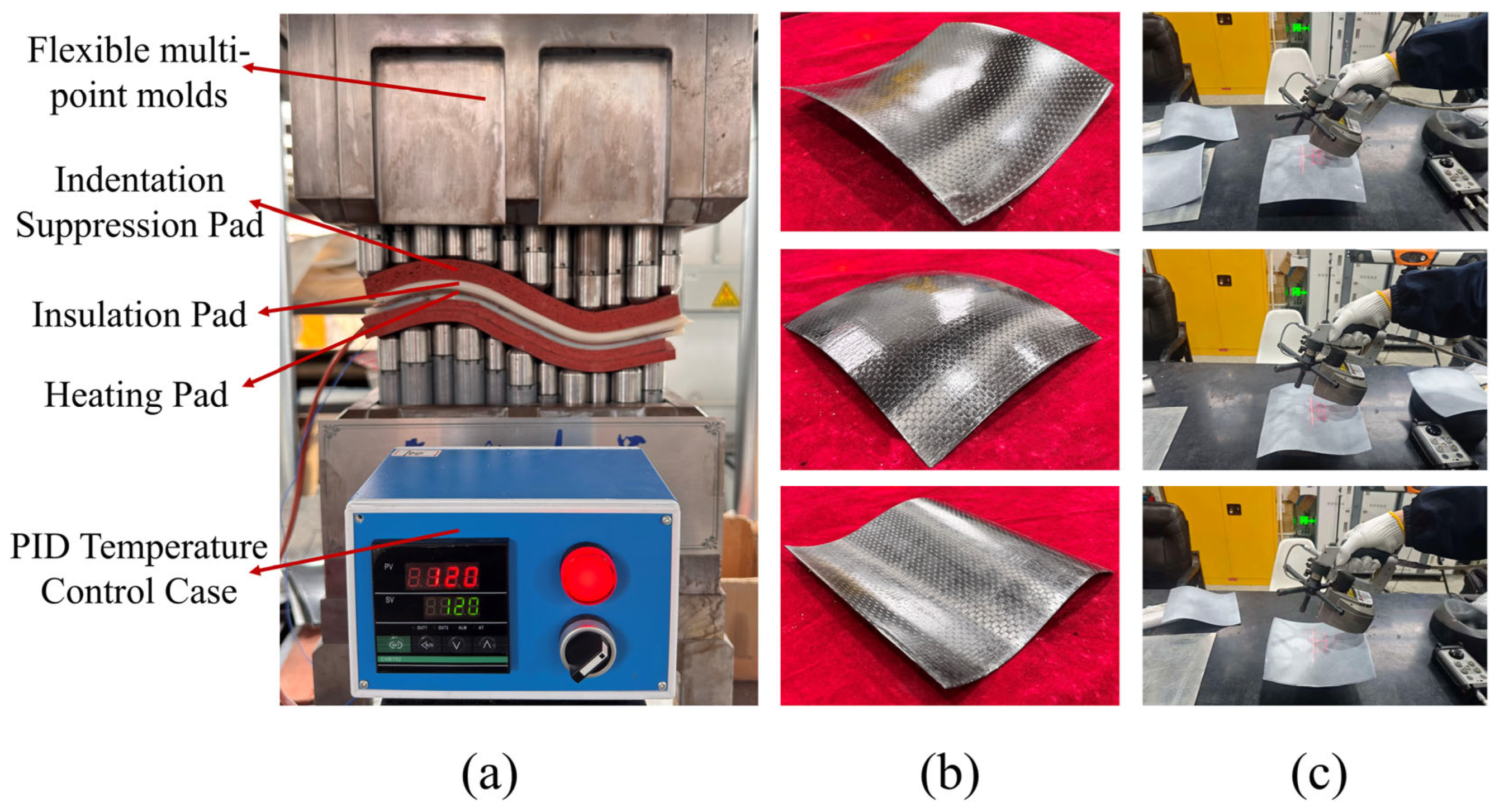

2. Robot-Assisted Precision Driving System

2.1. Flexible Mold Shape Regulation System

2.2. Flexible Mold Shape Errors Measurement System

3. Analysis of RAPDS Errors

3.1. Correlation Factors Analysis

3.2. Significant Factors Analysis

4. Bi-Level Optimized BPNN Error Prediction Modeling

4.1. BPNN Model

4.2. Bi-Level Optimization Strategy

4.2.1. BO-Based Hyperparameter Optimization

4.2.2. ASFSSA-Based Weight and Bias Initialization

4.3. Data Validation

5. Compensation for RAPDS Adjustment Errors

5.1. Compensation Theory

5.2. Compensation Experiment

6. Discussions

6.1. Error Adjustment on Baseline Shape

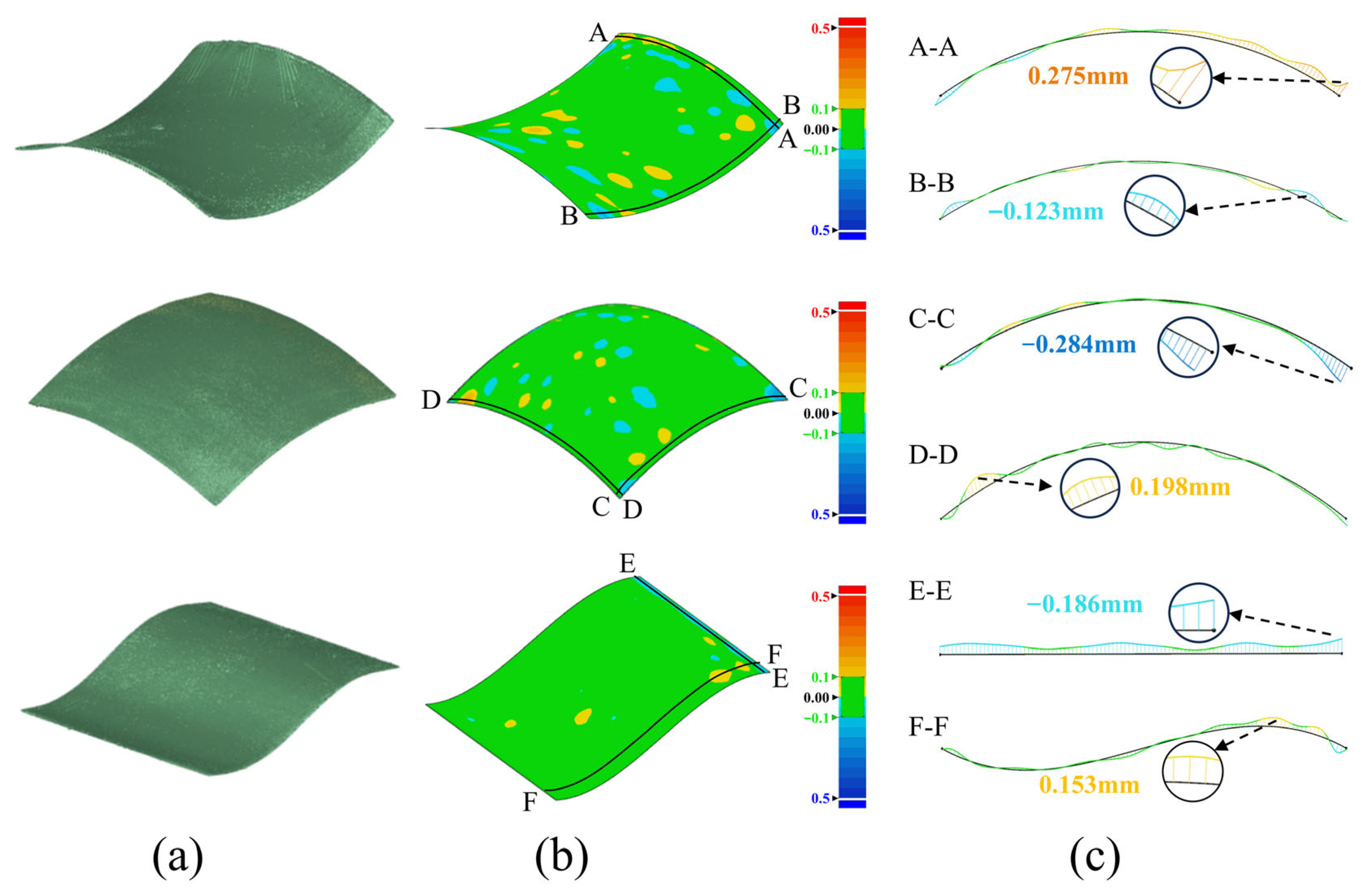

6.2. Evaluation of Method Effectiveness on Complex Shape

6.3. Evaluation of the Shape Accuracy of Composite Components

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- By integrating TOUC algorithm implemented in Rhino-Python with an industrial robot, a RAPDS was developed to efficiently and accurately convert the geometric curved surfaces of composite components into the forming curved surfaces of the flexible multi-point mold. Compared with the conventional fixed-mold manufacturing method for composite components, this system exhibits superior flexibility and adaptability in the composite forming and manufacturing process.

- (2)

- The proposed BO-ASFSSA-BPNN adopts a bi-level optimization framework that effectively enhances model stability, accuracy, and generalization. Compared with traditional BPNN variants, it achieves significantly lower prediction errors (RMSE = 0.0218 mm, MAE = 0.0148 mm) and a higher determination coefficient (R2 = 0.9973), providing reliable predictive support for the feedforward error compensation of the RAPDS and enabling high-precision and efficient composite forming.

- (3)

- The experimental results confirm that the proposed compensation strategy markedly enhances adjustment accuracy for both planar and complex composite surfaces. The maximum deviation in planar alignment was reduced from ±2.22 mm to ±0.12 mm, while over 85.0% of complex surface points fell within the ±0.05 mm tolerance. This strategy ensures stable, high-precision adjustment and significantly improves geometric conformity between the composite forming surface and the flexible multi-point mold, providing a robust basis for efficient flexible manufacturing.

- (4)

- The experimental results from the forming tests of composite components demonstrate that, during the continuous flexible manufacturing of three distinct complex geometries, more than 90.2% of the surface deviations of all formed components remain within ±0.1 mm. This finding confirms that the proposed flexible multi-point forming process can maintain stable geometric accuracy throughout continuous manufacturing. Moreover, the consistency and smoothness of the formed composite surfaces validate the process reliability and surface replication capability of the flexible multi-point mold.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, M.D.; Han, Q.G.; Liu, X.; Cheng, X.H.; Han, Z.W. Coupling bionic design and application of flow curved surface for carbon fiber composite fan blade. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 1797–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Kim, H.C.; Sommacal, S.; Stojcevski, F.; Soo, V.K.; Lipinski, W.; Morozov, E.; Henderson, L.C.; Compston, P.; Doolan, M. Improving mechanical and life cycle environmental performances of recycled CFRP automotive component by fibre architecture preservation. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 175, 107749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyano, Y.; Nakada, M.; Ichimura, J.; Hayakawa, E. Accelerated testing for long-term strength of innovative CFRP laminates for marine use. Compos. Part B Eng. 2008, 39, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tang, X.; Chen, C.; Peng, F.; Yan, R.; Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, J. High precision and efficiency robotic milling of complex parts: Challenges, approaches and trends. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Fairclough, J.P.A. A novel tooling-free carbon fibre reinforced polymer (CFRP) manufacturing method, double point incremental forming (DPIF) with direct electrical curing (DEC). Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 187, 108478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A.; Castorani, V.; Germani, M.; Marconi, M. Comparative life cycle assessment of low-pressure RTM, compression RTM and high-pressure RTM manufacturing processes to produce CFRP car hoods. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Z.; Rong, Q.; Zhou, W.; Lin, J. Effect of pin arrangement on formed shape with sparse multi-point flexible tool for creep age forming. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2019, 140, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Han, Q.; Huang, Y.; Shi, M.; Shi, H.; Ji, M.; Yang, C. Bioinspired ultra-fine hybrid nanocoating for improving strength and damage tolerance of composite fan blades in flexible manufacturing. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2025, 259, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.-Y.; Wang, S.-H.; Xu, X.-D.; Li, M.-Z. Numerical simulation for the multi-point stretch forming process of sheet metal. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.R.; Dean, T.A. The mechanics of multi-point sandwich forming. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2008, 48, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, E.; Li, M.; Li, R. Investigation of spring-back using a discrete steel pad in multi-point forming. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 4541–4551. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, M.; Fu, W. Principles and apparatus of multi-point forming for sheet metal. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 35, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.-B.; Chen, G.; Wang, W.-W.; Shen, Y.; Gu, Y. Deformation characteristics and forming force limits of multi-point forming with individually controlled force-displacement. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.-B.; Shen, Y.; Gu, Y. Influence of the deformation sequence on the shape accuracy of multi-point forming. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ou, H. A new flexible multi-point incremental sheet forming process with multi-layer sheets. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 322, 118214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; El-Aty, A.A.; Hu, S.; Cui, Z.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Cheng, C.; Tao, J.; Guo, X. Innovative high degree of freedom single-multipoint incremental forming system for manufacturing curved thin-walled components. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 1019–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Li, J.; Lu, Y. Integration and calibration of an in situ robotic manufacturing system for high-precision machining of large-span spacecraft brackets with associated datum. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 94, 102928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.W.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Jeong, W.; Lim, D.Y.; Lee, S.W. A vision-guided adaptive and optimized robotic fabric gripping system for garment manufacturing automation. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Qiu, T.; Liang, Z.; Shen, W.; Gao, Y.; Ma, S. Surface roughness online prediction using parallel ensemble learning in robotic side milling for aluminum alloy. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 235, 112932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W. An error compensation method for on-machine measuring blade with industrial robot. Measurement 2025, 242, 116039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Hu, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q. Adaptive remanufacturing for freeform surface parts based on linear laser scanner and robotic laser cladding. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 91, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Guo, K.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, D. Active vibration control in robotic grinding using six-axis acceleration feedback. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 214, 111379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, Z.; Chen, T.; Li, Z.; Yang, F.; Liang, X. A vision-based calibration method for aero-engine blade-robotic grinding system. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 2195–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.-Y.; Li, M.-Z. Multi-point forming of three-dimensional sheet metal and the control of the forming process. Int. J. Press. Ves. Pip. 2002, 79, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Li, M. Optimum path forming technique for sheet metal and its realization in multi-point forming. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 110, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, F.X.; Li, M.Z.; Cai, Z.Y. Research on the process of multi-point forming for the customized titanium alloy cranial prosthesis. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2007, 187–188, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J. Multi-label deep transfer learning method for coupling fault diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 212, 111327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, L.; Fürsterling, A.; Durocher, H.J.; Mouridsen, J.; Zhang, X. Learning-based object detection and localization for a mobile robot manipulator in SME production. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, H.; Li, J.; Lu, Y. Laser in-situ measurement in robotic machining of large-area complex parts. Measurement 2025, 241, 115718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Song, Q.; Fu, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, H.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Z.; Luan, Q.; Wang, H. Systematic error reduction in laser triangulation OMM: A study on measurement parameters and compensation techniques. Measurement 2025, 247, 116802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, Z.; Qian, F.; Yue, T.; Xu, T. Adaptive active noise feedforward compensation for exhaust ducts using a FIR Youla parametrization. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 170, 108803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, B.; Jiang, X.; Jia, F.; Li, N.; Nandi, A.K. Applications of machine learning to machine fault diagnosis: A review and roadmap. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 138, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, Q.; Pan, W.; Wang, W.; Ge, E. DeviationGAN: A generative end-to-end approach for the deviation prediction of sheet metal assembly. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 204, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yue, C.; Yu, M.; Song, Y.; Cui, P.; Yu, Y. Research on fault diagnosis strategy of air-conditioning system based on signal demodulation and BPNN-PCA. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 158, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xie, L.; Chen, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, K. Estimation of Weibull distribution using the back-propagation neural network for fatigue failure data. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2025, 82, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Hu, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Su, X.; Li, Z.; Tian, W. Digital twin modeling of the robotic gluing system for predicting the quality of glue lines and optimizing gluing parameters. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 1074–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ge, Q. Adaptive STCPF for UCA pose estimation with improved GA-BPNN and multiple fading factors. Neurocomputing 2024, 575, 127238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Liu, M.; Chen, J. Frequency-temporal-logic-based bearing fault diagnosis and fault interpretation using Bayesian optimization with Bayesian neural networks. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 145, 106951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, W.; Cheng, X.; Sun, J.; Ding, R.; Yue, D.; Han, Q. Curvature-driven regionally sampling and machine learning for forming error measurement in composite manufacturing. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 238, 113231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Han, Q.; Cheng, X.; Shi, H.; Ding, R.; Shi, M.; Liu, C. A data-driven computational optimization framework for designing thin-walled lenticular deployable composite boom with optimal load-bearing and folding capabilities. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 203, 112244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, D. Adaptive Spiral Flying Sparrow Search Algorithm. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 6505253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | X1 (mm) | X2 (mm) | X3 | X4 (°C) | X5 (mm) | X6 | Y (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.31 |

| 2 | 100.00 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.56 |

| 3 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.67 |

| 4 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 104.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 1.03 |

| 5 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.73 |

| 6 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 17.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 1.55 |

| 7 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.77 |

| 8 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 17.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 1.53 |

| 9 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 1.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 0.33 |

| 10 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 4.00 | 0.59 |

| 11 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 0.32 |

| 12 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.26 |

| 13 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.04 |

| 14 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.88 |

| 15 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 104.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 0.77 |

| 16 | 0.02 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.23 |

| 17 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.89 |

| 18 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.53 |

| 19 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 0.61 |

| 20 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 104.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 0.98 |

| 21 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 2.00 | 0.53 |

| 22 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 17.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 0.21 |

| 23 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.21 |

| 24 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.46 |

| 25 | 100.0 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 23.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 1.33 |

| 26 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 104.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 1.37 |

| 27 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 0.71 |

| 28 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.62 |

| 29 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 2.00 | 0.88 |

| 30 | 0.02 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.47 |

| 31 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.02 |

| 32 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 1.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 0.99 |

| 33 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 2.00 | 0.71 |

| 34 | 100.00 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.44 |

| 35 | 100.00 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.55 |

| 36 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.73 |

| 37 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.66 |

| 38 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 17.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 0.19 |

| 39 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 23.00 | −1.50 | 3.00 | 0.26 |

| 40 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.45 |

| 41 | 0.02 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 23.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 1.33 |

| 42 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 23.00 | 1.50 | 3.00 | 1.47 |

| 43 | 0.02 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.03 |

| 44 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 4.00 | 0.91 |

| 45 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.46 |

| 46 | 100.00 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 1.77 |

| 47 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.76 |

| 48 | 50.01 | 15.00 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 1.50 | 4.00 | 0.73 |

| 49 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 1.01 |

| 50 | 0.02 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 17.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.49 |

| 51 | 50.01 | 176.84 | 52.00 | 20.00 | −1.50 | 4.00 | 0.83 |

| 52 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 52.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.79 |

| 53 | 100.00 | 93.67 | 104.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.85 |

| 54 | 50.01 | 93.67 | 1.00 | 23.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.44 |

| Factor | PCC (r) | SRC (ρ) | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Height (mm) | 0.663 | 0.636 | 63.722 | 0.001 |

| Radial Distance (mm) | 0.178 | 0.185 | 4.210 | 0.050 |

| Adjustment Sequence | 0.247 | 0.284 | 34.961 | 0.001 |

| Ambient Temperature (°C) | −0.050 | −0.040 | 0.454 | 0.507 |

| Initial Error (mm) | 0.089 | 0.073 | 1.143 | 0.295 |

| Motor Speed Level | 0.065 | 0.059 | 0.454 | 0.504 |

| Models | R2 | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | Training Time/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPNN | 0.9089 | 0.1112 | 0.0859 | 12.4% | 2.00 |

| BO-BPNN | 0.9504 | 0.0468 | 0.0358 | 6.6% | 4.19 |

| ASFSSA-BPNN | 0.9699 | 0.0372 | 0.0256 | 4.4% | 20.00 |

| BO-ASFSSA-BPNN | 0.9973 | 0.0218 | 0.0148 | 2.2% | 16.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Shi, H.; Cheng, X.; Ding, R.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Hao, S.; Yan, J.; Han, Q. A Machine Learning-Optimized Robot-Assisted Driving System for Efficient Flexible Forming of Composite Curved Components. Eng 2025, 6, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120356

Wang W, Shi H, Cheng X, Ding R, Sun J, Li Y, Wang X, Hao S, Yan J, Han Q. A Machine Learning-Optimized Robot-Assisted Driving System for Efficient Flexible Forming of Composite Curved Components. Eng. 2025; 6(12):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120356

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wenliang, Hexuan Shi, Xianhe Cheng, Rundong Ding, Junwei Sun, Yuan Li, Xingjian Wang, Shouzhi Hao, Jing Yan, and Qigang Han. 2025. "A Machine Learning-Optimized Robot-Assisted Driving System for Efficient Flexible Forming of Composite Curved Components" Eng 6, no. 12: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120356

APA StyleWang, W., Shi, H., Cheng, X., Ding, R., Sun, J., Li, Y., Wang, X., Hao, S., Yan, J., & Han, Q. (2025). A Machine Learning-Optimized Robot-Assisted Driving System for Efficient Flexible Forming of Composite Curved Components. Eng, 6(12), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120356