A Machine Learning Approach to Determine the Band Gap Energy of High-Entropy Oxides Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

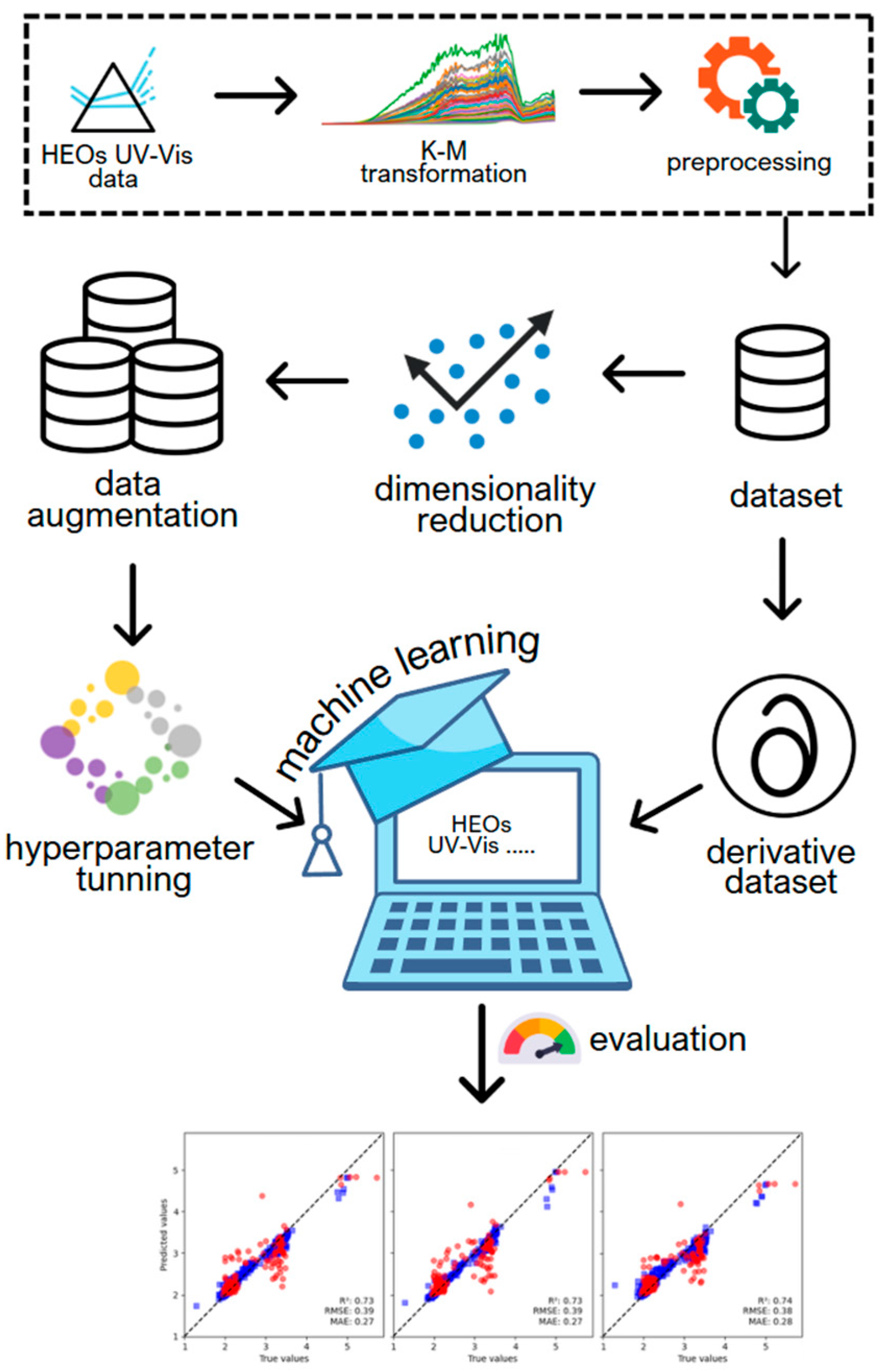

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spectra Dataset, Kubelka-Munk Transformation, and Band Gap Calculation

2.2. Data Pre-Processing

2.3. Machine Learning Algorithms

2.4. Data Augmentation Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Models Performance Evaluation

3.2. Model Hyperparameter Tuning

3.3. Data Augmentation

3.4. Application Development for Visualization and Decision Making

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cantor, B.; Chang, I.T.H.; Knight, P.; Vincent, A.J.B. Microstructural development in equiatomic multicomponent alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Chen, S.K.; Lin, S.J.; Gan, J.Y.; Chin, T.S.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Chang, S.Y. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: Novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2004, 6, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K.; Yeh, J.-W.; Bhattacharjee, P.P.; DeHosson, J.T.M. High entropy alloys: Key issues under passionate debate. Scr. Mater. 2020, 188, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rost, C.M.; Sachet, E.; Borman, T.; Moballegh, A.; Dickey, E.C.; Hou, D.; Jones, J.L.; Curtarolo, S.; Maria, J.P. Entropy-stabilized oxides. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gild, J.; Zhang, Y.; Harrington, T.; Jiang, S.; Hu, T.; Quinn, M.C.; Mellor, W.M.; Zhou, N.; Vecchio, K.; Luo, J. High-Entropy Metal Diborides: A New Class of High-Entropy Materials and a New Type of Ultrahigh Temperature Ceramics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Niu, B.; Lei, L.; Wang, W. High-entropy carbide: A novel class of multicomponent ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 22014–22018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsse, S.; Nguyen, M.H.; Senkov, O.N.; Miracle, D.B. Database on the mechanical properties of high entropy alloys and complex concentrated alloys. Data Brief 2018, 21, 2664–2678, Erratum in Data Brief 2020, 32, 106216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.J.; Chen, Y.L.; Chen, S.K.; Yeh, J.W.; Shun, T.T.; Tsau, C.H.; Lin, S.J.; Chang, S.Y. Microstructure characterization of AlxCoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system with multiprincipal elements. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2005, 36, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.W.; Lin, S.J. Breakthrough applications of high-entropy materials. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 3129–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oses, C.; Toher, C.; Curtarolo, S. High-entropy ceramics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.H.; Yeh, J.W. High-entropy alloys: A critical review. Mater. Res. Lett. 2014, 2, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.P.; Raabe, D.; Ritchie, R.O. High-entropy alloys. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Velasco, L.; Breitung, B.; Presser, V. High-Entropy Energy Materials in the Age of Big Data: A Critical Guide to Next-Generation Synthesis and Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.D.; Sun, X.; Briceño, G.; Lou, Y.; Wang, K.A.; Chang, H.; Wallace-Freedman, W.G.; Chen, S.W.; Schultz, P.G. A combinatorial approach to materials discovery. Science 1995, 268, 1738–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potyrailo, R.; Rajan, K.; Stoewe, K.; Takeuchi, I.; Chisholm, B.; Lam, H. Combinatorial and high-throughput screening of materials libraries: Review of state of the art. ACS Comb. Sci. 2011, 13, 579–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, T.; Music, D.; Takahashi, T.; Schneider, J.M. Combinatorial thin film materials science: From alloy discovery and optimization to alloy design. Thin Solid Films 2012, 520, 5491–5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, L.; Castillo, J.S.; Kante, M.V.; Olaya, J.J.; Friederich, P.; Hahn, H. Phase–Property Diagrams for Multicomponent Oxide Systems toward Materials Libraries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilmard, M. Effects of aluminum on the structural and electrochemical properties of LiNiO2. J. Power Sources 2003, 115, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceder, G.; Chiang, Y.-M.; Sadoway, D.R.; Aydinol, M.K.; Jang, Y.-I.; Huang, B. Identification of cathode materials for lithium batteries guided by first-principles calculations. Nature 1998, 392, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollice, R.; Gomes, G.D.P.; Aldeghi, M.; Hickman, R.J.; Krenn, M.; Lavigne, C.; Lindner-D’Addario, M.; Nigam, A.; Ser, C.T.; Yao, Z.; et al. Data-Driven Strategies for Accelerated Materials Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Gucci, F.; Zhu, H.; Chen, K.; Reece, M.J. Data-Driven Design of Ecofriendly Thermoelectric High-Entropy Sulfides. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 13027–13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.M. A Design-to-Device Pipeline for Data-Driven Materials Discovery. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z. Machine learning: Accelerating materials development for energy storage and conversion. InfoMat 2020, 2, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, A.; Kranthiraja, K. A high throughput molecular screening for organic electronics via machine learning: Present status and perspective. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 59, SD0801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirklin, S.; Saal, J.E.; Meredig, B.; Thompson, A.; Doak, J.W.; Aykol, M.; Rühl, S.; Wolverton, C. The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): Assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2015, 1, 15010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J.; Wolverton, C.; Ceder, G. Toward Computational Materials Design: The Impact of Density Functional Theory on Materials Research. MRS Bull. 2006, 31, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhakar, M.; Khandelwal, A.; Jha, S.K.; Kante, M.V.; Keßler, P.; Lemmer, U.; Hahn, H.; Aghassi-Hagmann, J.; Colsmann, A.; Breitung, B.; et al. High-Throughput Screening of High-Entropy Fluorite-Type Oxides as Potential Candidates for Photovoltaic Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2204337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweidler, S.; Schopmans, H.; Reiser, P.; Boltynjuk, E.; Olaya, J.J.; Singaraju, S.A.; Fischer, F.; Hahn, H.; Friederich, P.; Velasco, L. Synthesis and Characterization of High-Entropy CrMoNbTaVW Thin Films Using High-Throughput Methods. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2200870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Wang, Q.; Schiele, A.; Chellali, M.R.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Wang, D.; Brezesinski, T.; Hahn, H.; Velasco, L.; Breitung, B. High-Entropy Oxides: Fundamental Aspects and Electrochemical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, G.; Wynn, A.P.; Handley, C.M.; Freeman, C.L. Phase stability and distortion in high-entropy oxides. Acta Mater. 2018, 146, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hu, T.; Gild, J.; Zhou, N.; Nie, J.; Qin, M.; Harrington, T.; Vecchio, K.; Luo, J. A new class of high-entropy perovskite oxides. Scr. Mater. 2018, 142, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellali, M.R.; Sarkar, A.; Nandam, S.H.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Breitung, B.; Hahn, H.; Velasco, L. On the homogeneity of high entropy oxides: An investigation at the atomic scale. Scr. Mater. 2019, 166, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kruk, R.; Hahn, H. Magnetic properties of high entropy oxides. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérardan, D.; Franger, S.; Dragoe, D.; Meena, A.K.; Dragoe, N. Colossal dielectric constant in high entropy oxides. Phys. Status Solidi–Rapid Res. Lett. 2016, 10, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Velasco, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Talasila, G.; de Biasi, L.; Kübel, C.; Brezesinski, T.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Hahn, H.; et al. High entropy oxides for reversible energy storage. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hossain, M.D.; Du, Y.; Chambers, S.A. Exploring the potential of high entropy perovskite oxides as catalysts for water oxidation. Nano Today 2022, 47, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Stenzel, D.; Azmi, R.; Najib, S.; Wang, K.; Jeong, J.; Sarkar, A.; Wang, Q.; Sukkurji, P.A.; Bergfeldt, T.; et al. Spinel to Rock-Salt Transformation in High Entropy Oxides with Li Incorporation. Electrochem 2020, 1, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Eggert, B.; Velasco, L.; Mu, X.; Lill, J.; Ollefs, K.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Wende, H.; Kruk, R.; Brand, R.A.; et al. Role of intermediate 4 f states in tuning the band structure of high entropy oxides. APL Mater. 2020, 8, 051111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, S.; Segundo, I.R.; Freitas, E.; Vasilevskiy, M.; Carneiro, J.; Tavares, C.J. Use and misuse of the Kubelka-Munk function to obtain the band gap energy from diffuse reflectance measurements. Solid State Commun. 2022, 341, 114573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo-Morales, A.; Ruiz-López, I.I.; Ruiz-Peralta, M.D.; Tepech-Carrillo, L.; Sánchez-Cantú, M.; Moreno-Orea, J.E. Automated method for the determination of the band gap energy of pure and mixed powder samples using diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.E.; Ruiz-López, I. GapExtractor, Mendeley Data, V1; Benemerita Universidad Autonoma de Puebla: Puebla, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mursyalaat, V.; Variani, V.I.; Arsyad, W.O.S.; Firihu, M.Z. The development of program for calculating the band gap energy of semiconductor material based on UV-Vis spectrum using delphi 7.0. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2498, 012042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.; Jacobs, R. Opportunities and Challenges for Machine Learning in Materials Science. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2020, 50, 71–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T.; Kusne, A.G.; Ramprasad, R. Machine Learning in Materials Science. In Reviews in Computational Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 186–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Tayara, H.; Chong, K.T. Prediction of organic material band gaps using graph attention network. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 220, 112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L. Python 3 Reference Manual: (Python Documentation Manual Part 2); CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa, R.M.; Yacout, S.; Bassetto, S. Developing machine-learning regression model with Logical Analysis of Data (LAD). Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, W. A Review of Ensemble Learning Algorithms Used in Remote Sensing Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, J.; Villena, F.; Hoyos, J.P.; Riquelme, V.; Royer, M.; Ramírez, H.; Peypouquet, J. Predicting no-show appointments in a pediatric hospital in Chile using machine learning. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2023, 26, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietterich, T.G. Ensemble Methods in Machine Learning. In Multiple Classifier Systems, MCS 2000; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the First International Workshop, MCS 2000 Cagliari, Italy, 21–23 June 2000; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 1857, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: A paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning, 1st ed.; Information Science and Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, F.-A.; de Rainville, F.-M.; Gardner, M.-A.G.; Parizeau, M.; Gagné, C. DEAP: Evolutionary algorithms made easy. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 2171–2175. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas, R. Rodrigo-Arenas/Sklearn-Genetic-Opt. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/rodrigo-arenas/Sklearn-genetic-opt (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, P.; Torgo, L.; Ribeiro, R.P. SMOGN: A Pre-Processing Approach for Imbalanced Regression. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Learning with Imbalanced Domains: Theory and Applications, PMLR, Skopje, North Macedonia, 22 September 2017; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?–Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuła, P.; Pacia, M.; Macyk, W. How To Correctly Determine the Band GatoEnergy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV–Vis Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6814–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welter, E.S.; Garg, S.; Gläser, R.; Goepel, M. Methodological Investigation of the Band Gap Determination of Solid Semiconductors via UV/Vis Spectroscopy. ChemPhotoChem 2023, 7, e202300001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Siemenn, A.E. PV-Lab/Automatic-Band-Gap-Extractor. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/PV-Lab/Automatic-Band-Gap-Extractor (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Escobedo Morales, A.; Sánchez Mora, E.; Pal, U. Use of Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy for Optical Characterization of Un-Supported Nanostructures. Rev. Mex. Fis. 2007, 53, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zimnyakov, D.A.; Sevrugin, A.V.; Yuvchenko, S.A.; Fedorov, F.S.; Tretyachenko, E.V.; Vikulova, M.A.; Kovaleva, D.S.; Krugova, E.Y.; Gorokhovsky, A.V. Data on energy-band-gap characteristics of composite nanoparticles obtained by modification of the amorphous potassium polytitanate in aqueous solutions of transition metal salts. Data Brief 2016, 7, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Hyperparameter | Values Range for Genetic Search |

|---|---|---|

| AdaBoost | n_estimators learning_rate loss | Integer(50,200) Continuous(0.01,1,distribution = ‘log-uniform’) [Linear, square, exponential] |

| Bagging | n_estimators max_samples max_features bootstrap bootstrap_features | Integer(50,200) Continuous(0.1, 1.0, distribution = ‘log-uniform’) Continuous(0.1, 1.0, distribution = ‘log-uniform’) [True, False] [True, False] |

| Extra-Trees | n_estimators bootstrap max_depth max_features min_samples_split min_samples_leaf | Integer(50,200) True, False [10, 30, 50, None] [sqrt, log2, 1.0] Integer(2, 10) Integer(2, 4) |

| Gradient Boosting | n_estimators loss max_depth max_features min_samples_split min_samples_leaf | Integer(50,200) [squared_error, absolute_error] [10, 30, 50, None] [sqrt, log2, 1.0] Integer(2, 10) Integer(2, 4) |

| LightGBM | n_estimators learning_rate max_depth num_leaves min_child_samples subsample colsample_bytree reg_alpha reg_lambda | Integer(50, 200) Continuous(0.01, 0.3, distribution = log-uniform) Integer(10, 30) Integer(20, 100) Integer(5, 20) Continuous(0.7, 1.0, distribution = uniform) Continuous(0.7, 1.0, distribution = uniform) Continuous(1 × 10−3,1.0, distribution = log-uniform) Continuous(1 × 10−3, 1.0, distribution = log-uniform) |

| Random Forest | n_estimators bootstrap criterion max_depth max_features min_samples_split min_samples_leaf | Integer(50, 1000) [True, False] [squared_error, absolute_error, friedman_mse, poisson] 10, 30, 50, None [sqrt, log2, 1.0] Integer(2, 10) Integer(1, 4) |

| XGBoost | n_estimators learning_rate subsample max_depth | Integer(50, 200) Continuous(0.05, 0.5) [0.5, 0.75, 1] [3, 6, 10] |

| k-Nearest Neighbors | n_neighbors weights p | Integer(1, 20) uniform, distance Integer(1, 2) |

| Trained Algorithm—Model | Test-DS | Der-Test-DS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (eV) | RMSE | R2 | MAE (eV) | RMSE | R2 | |

| AdaBoost | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.38 ↓ |

| Bagging | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.50 ↓ |

| Extra-Trees | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 0.71 ↓ |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.53 ↓ |

| LightGBM | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.60 ↓ |

| Random Forest | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.61 ↓ |

| XGBoost | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.45 ↓ |

| k-Nearest Neighbors | 0.50 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.17 ↑ |

| Model | Hyperparameter | Before Genetic Search | After Genetic. Search | Augmented Data Method 1 + Genetic Search | Augmented Data Method 2 SMOGN + Genetic Search |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AdaBoost | n_estimators | 50 | 139 | 171 | 57 |

| learning_rate | 1.0 | 0.0141 | 0.1428 | 0.0596 | |

| loss | linear | exponential | square | exponential | |

| Bagging | n_estimators | 10 | 192 | 151 | 77 |

| max_samples | 1.0 | 0.7630 | 0.9920 | 0.9549 | |

| max_features | 1.0 | 0.2138 | 0.3106 | 0.2219 | |

| bootstrap | True | False | True | False | |

| bootstrap_features | False | True | True | True | |

| Extra-Trees | n_estimators | 100 | 70 | 145 | 128 |

| bootstrap | False | False | False | False | |

| max_depth | None | 30 | 30 | None | |

| max_features | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| min_samples_split | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gradient Boosting | n_estimators | 100 | 163 | 194 | 178 |

| loss | squared_error | absolute_error | squared_error | absolute_error | |

| max_depth | 3 | 50 | 10 | None | |

| max_features | None | 1.0 | log2 | log2 | |

| min_samples_split | 2 | 7 | 7 | 6 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| LightGBM | n_estimators | 100 | 154 | 199 | 163 |

| learning_rate | 0.1 | 0.03567 | 0.1590 | 0.0950 | |

| max_depth | −1 | 17 | 17 | 17 | |

| num_leaves | 31 | 33 | 42 | 50 | |

| min_child_samples | 20 | 5 | 13 | 9 | |

| subsample | 1.0 | 0.7893 | 0.7272 | 0.8161 | |

| colsample_bytree | 1.0 | 0.9177 | 0.8870 | 0.7374 | |

| reg_alpha | 0.0 | 0.0515 | 0.5198 | 0.0017 | |

| reg_lambda | 0.0 | 0.1838 | 0.0065 | 0.03193 | |

| Random Forest | n_estimators | 100 | 153 | 100 | 885 |

| bootstrap | True | True | True | False | |

| criterion | squared_error | Poisson | squared_error | absolute_error | |

| max_depth | None | 30 | None | 30 | |

| max_features | 1.0 | Sqrt | 1.0 | sqrt | |

| min_samples_split | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | |

| min_samples_leaf | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| XGBoost | n_estimators | None | 91 | None | 136 |

| learning_rate | None | 0.0702 | None | 0.1022 | |

| subsample | None | 1 | None | 0.5 | |

| max_depth | None | 6 | None | 10 | |

| k-nearest neighbors | n_neighbors | 5 | 8 | 5 | 6 |

| weights | uniform | Distance | uniform | Distance | |

| p | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Model | Hyperparameter Tuning | Data augmentation Method 1 + Genetic Search | Data augmentation Method 2 + Genetic Search | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE (eV) | RMSE | R2 | MAE (eV) | RMSE | R2 | MAE (eV) | RMSE | R2 | |

| AdaBoost | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.58 ↑ | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.30 ↓ | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.59 ↑ |

| Bagging | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.73 ↑ | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.74 ↑ |

| Extra-Trees | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.73 ↑ | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.71 ↓ | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.72 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.68 ↑ | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.73 ↑ | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.63 ↑ |

| LightGBM | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.68 ↑ | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.67 ↓ | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.69 ↑ |

| Random Forest | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.74 ↑ | 0.31 | 0.41 | 0.70 ↓ | 0.28 | 0.40 | 0.71 ↓ |

| XGBoost | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.66 ↑ | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.68 ↑ | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.70 ↑ |

| k-Nearest Neighbors | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.31 ↑ | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.33 ↑ | 0.44 | 0.58 | 0.40 ↑↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoyos-Sanchez, J.P.; Hahn, H.; Jha, S.K.; Schweidler, S.; Velasco, L. A Machine Learning Approach to Determine the Band Gap Energy of High-Entropy Oxides Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy. Eng 2025, 6, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120340

Hoyos-Sanchez JP, Hahn H, Jha SK, Schweidler S, Velasco L. A Machine Learning Approach to Determine the Band Gap Energy of High-Entropy Oxides Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy. Eng. 2025; 6(12):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120340

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoyos-Sanchez, Juan P., Horst Hahn, Shikhar K. Jha, Simon Schweidler, and Leonardo Velasco. 2025. "A Machine Learning Approach to Determine the Band Gap Energy of High-Entropy Oxides Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy" Eng 6, no. 12: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120340

APA StyleHoyos-Sanchez, J. P., Hahn, H., Jha, S. K., Schweidler, S., & Velasco, L. (2025). A Machine Learning Approach to Determine the Band Gap Energy of High-Entropy Oxides Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy. Eng, 6(12), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120340