Advanced Cellular Models for Neurodegenerative Diseases and PFAS-Related Environmental Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

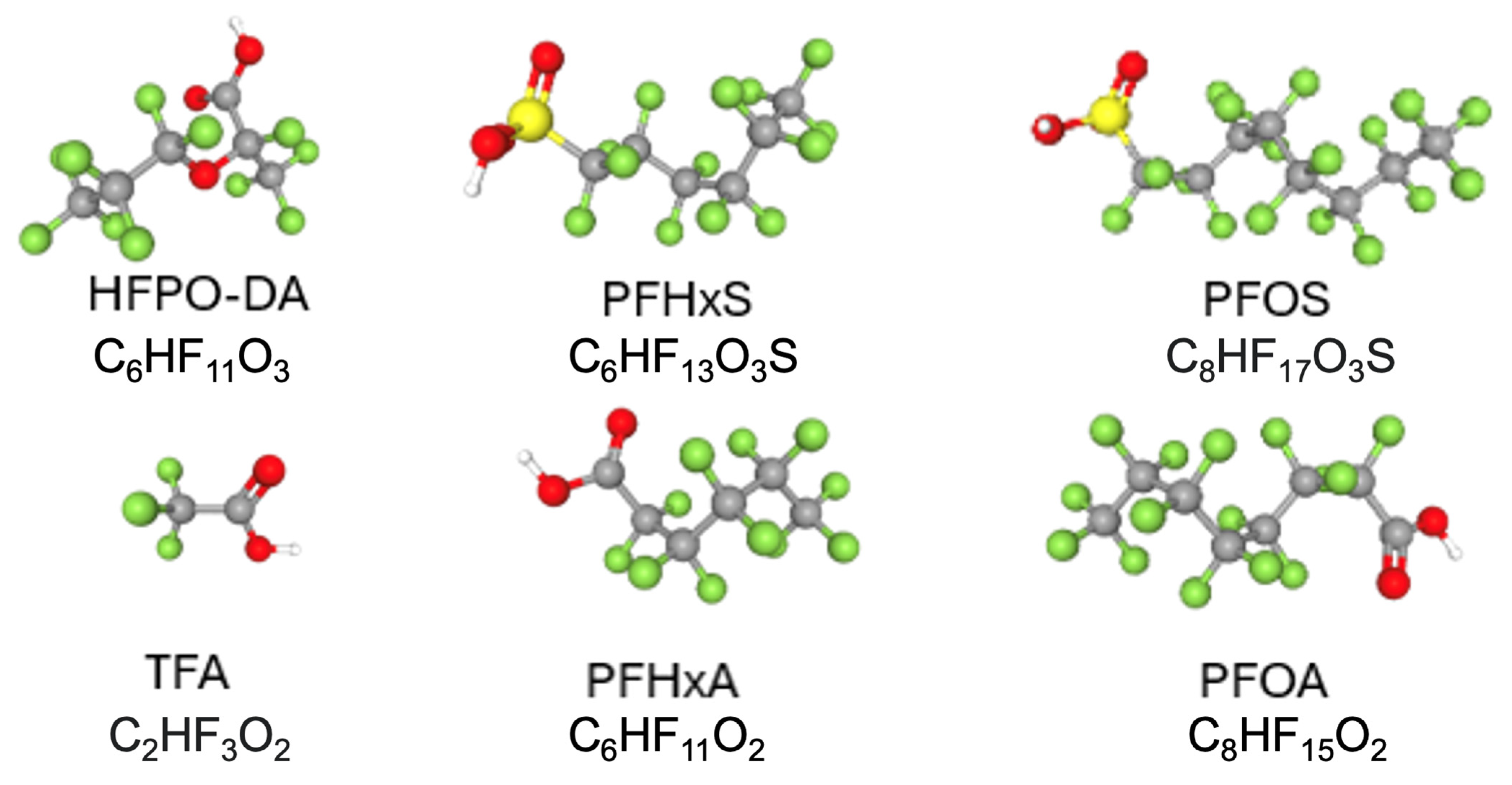

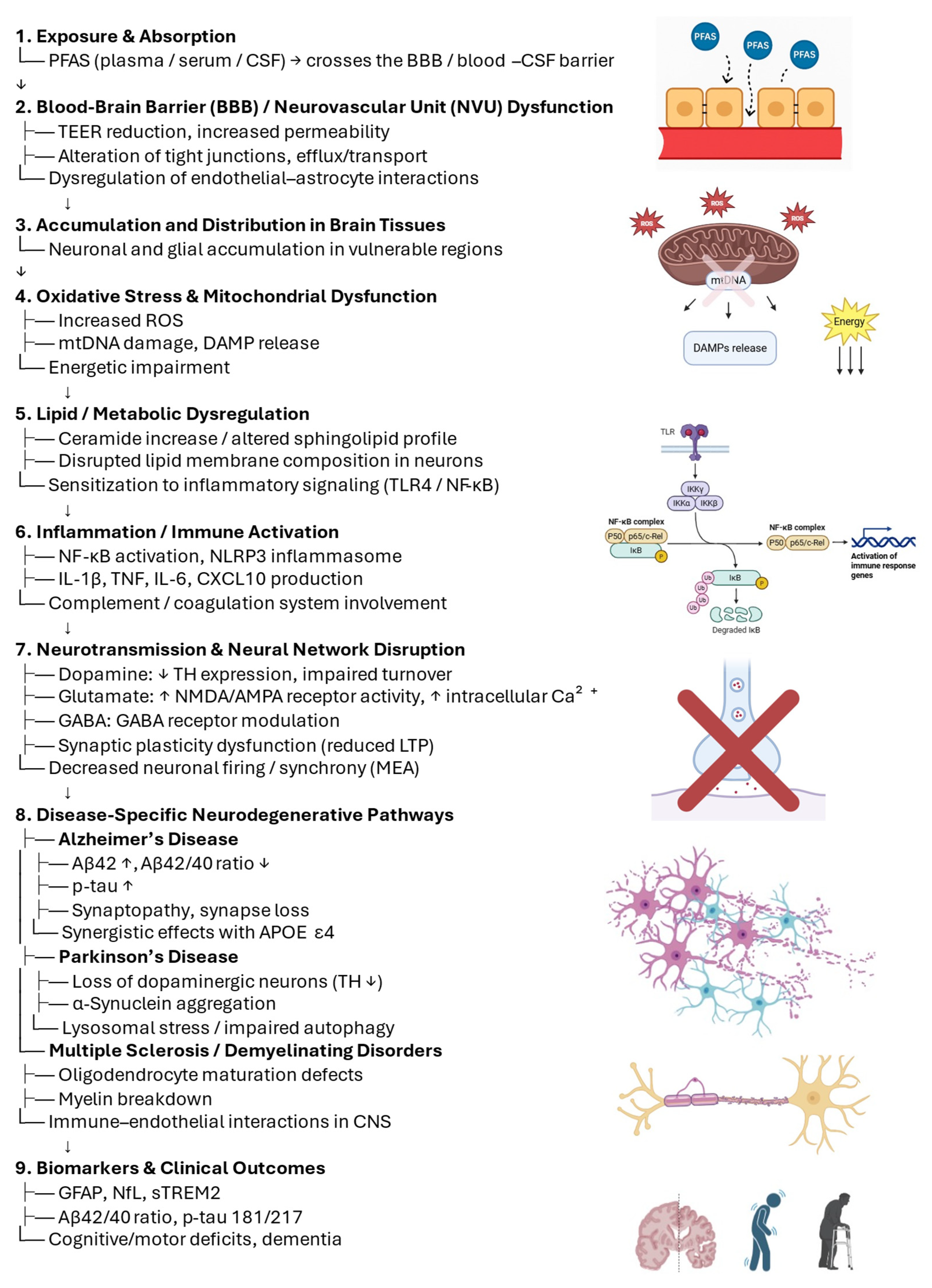

Environmental Pollutants and Neurodegeneration

2. Alzheimer’s Disease: Organoids and 3D Cell Models

3. Parkinson’s Disease: Midbrain Organoids and Dopaminergic Models

4. Multiple Sclerosis: 3D Glia-Enriched Models and Neuroimmune Interactions

5. Leveraging 3D Models to Address Mechanistic Insights

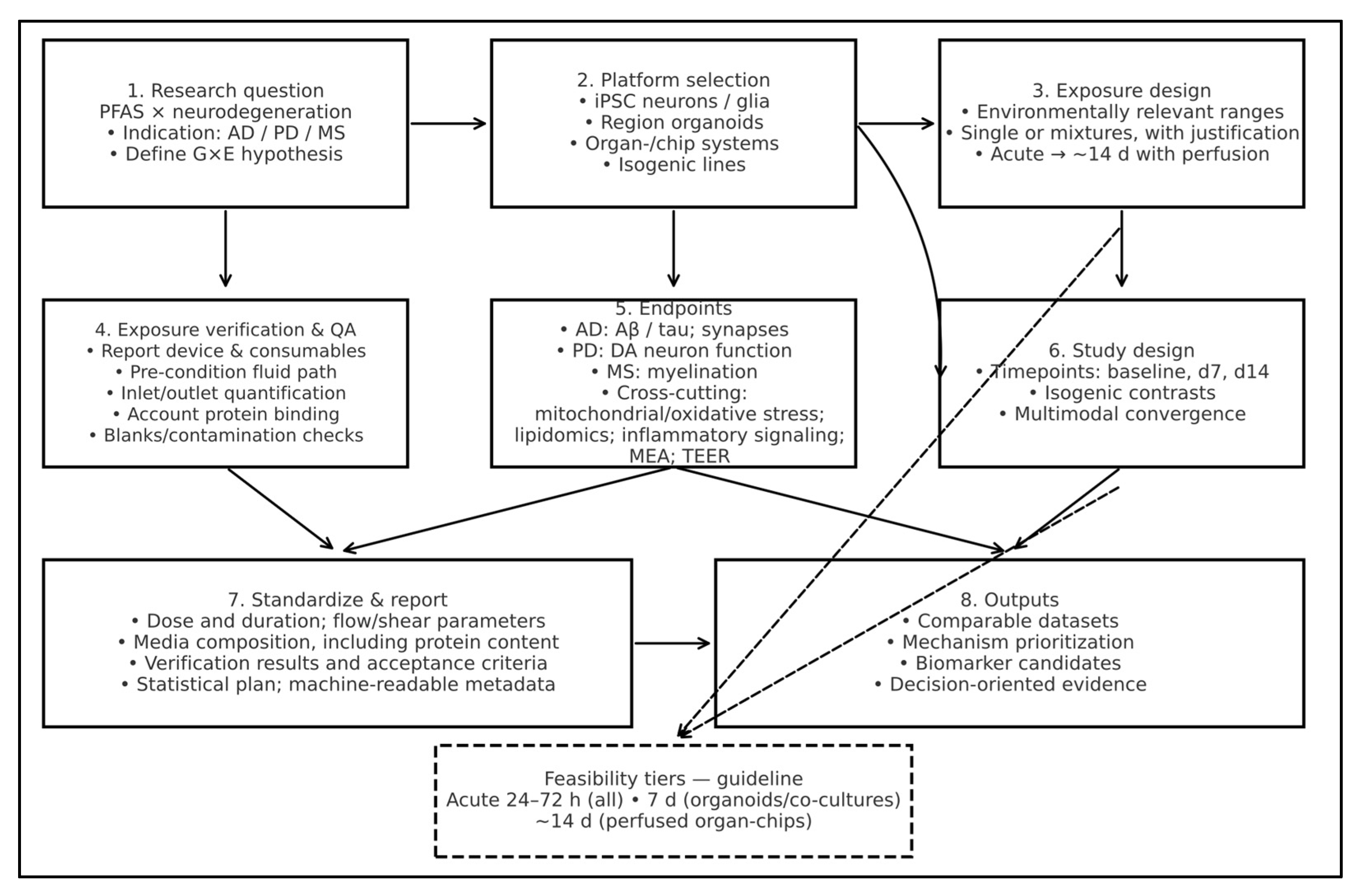

5.1. Platform Selection for PFAS × Neurodegeneration

5.2. Extending Model Applicability to Other Environmental Risk Factors

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lau, C.; Anitole, K.; Hodes, C.; Lai, D.; Pfahles-Hutchens, A.; Seed, J. Perfluoroalkyl Acids: A review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 99, 366–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, L.; Ji, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, X.-M.; Wang, S.-L. Perfluorooctane sulfonate disrupts the blood brain barrier through the crosstalk between endothelial cells and astrocytes in mice. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, K.; Power, M.C. Persistent organic pollutants and mortality in the United States, NHANES 1999–2011. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Andersen, E.W.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Nielsen, F.; Mølbak, K.; Weihe, P.; Heilmann, C. Serum vaccine antibody concentrations in children exposed to perfluorinated compounds. JAMA 2012, 307, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motsinger-Reif, A.A.; Reif, D.M.; Akhtari, F.S.; House, J.S.; Campbell, C.R.; Messier, K.P.; Fargo, D.C.; Bowen, T.A.; Nadadur, S.S.; Schmitt, C.P.; et al. Gene-environment interactions within a precision environmental health framework. Cell Genom. 2024, 4, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvi, D.; Christiani, D.C.; Coull, B.; Højlund, K.; Nielsen, F.; Audouze, K.; Su, L.; Weihe, P.; Grandjean, P. Gene-environment interactions in the associations of PFAS exposure with insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in a Faroese cohort followed from birth to adulthood. Environ. Res. 2023, 226, 115600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinals, R.L.; Tsai, L.-H. Building in vitro models of the brain to understand the role of APOE in Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, e202201542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakulski, K.M.; Seo, Y.A.; Hickman, R.C.; Brandt, D.; Vadari, H.S.; Hu, H.; Park, S.K. Heavy metals exposure and alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 1215–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, L.; Martins, M.; Côrte-Real, M.; Outeiro, T.F.; Chaves, S.R.; Rego, A. The neurotoxicity of pesticides: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Chemosphere 2025, 377, 144348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, J.; Kitazawa, M. The emerging risk of exposure to air pollution on cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease–evidence from epidemiological and animal studies. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadzadeh, M.; Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Grafman, J. Air pollution: A latent key driving force of dementia. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Bradner, J.M.; Stout, K.A.; Caudle, W.M. Alteration to Dopaminergic Synapses Following Exposure to Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS), in Vitro and in Vivo. Med. Sci. 2016, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown-Leung, J.M.; Cannon, J.R. Neurotransmission Targets of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Neurotoxicity: Mechanisms and Potential Implications for Adverse Neurological Outcomes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1312–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; de Wit, N.M.; van der Flier, W.M.; de Vries, H.E. The blood brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 89, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, P.; Kumari, S.; Bagri, K.; Deshmukh, R. Ceramide: A central regulator in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Ojala, J.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress activate inflammasomes: Impact on the aging process and age-related diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 2999–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiblich, H.; Schlütter, A.; Golenbock, D.T.; Latz, E.; Martinez-Martinez, P.; Heneka, M.T. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in microglia: The role of ceramide. J. Neurochem. 2017, 143, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, G.C.C.; Assmann, C.E.; Mostardeiro, V.B.; Alves, A.d.O.; da Rosa, J.R.; Pillat, M.M.; de Andrade, C.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Morsch, V.M.M.; da Cruz, I.B.M.; et al. Chlorpyrifos pesticide promotes oxidative stress and increases inflammatory states in BV-2 microglial cells: A role in neuroinflammation. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running, L.; Cristobal, J.R.; Karageorgiou, C.; Camdzic, M.; Aguilar, J.M.N.; Gokcumen, O.; Aga, D.S.; Atilla-Gokcumen, G.E. Investigating the Mechanism of Neurotoxic Effects of PFAS in Differentiated Neuronal Cells through Transcriptomics and Lipidomics Analysis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 4568–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagostena, L.; Rotondo, D.; Gualandris, D.; Calisi, A.; Lorusso, C.; Magnelli, V.; Dondero, F. Impact of Legacy Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) on GABA Receptor-Mediated Currents in Neuron-Like Neuroblastoma Cells: Insights into Neurotoxic Mechanisms and Health Implications. J. Xenobiot. 2024, 14, 1771–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; Garcia-Martin, J.; Marongiu, R. Editorial: Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: Past, present, and future. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 16, 1539837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azargoonjahromi, A. The duality of amyloid-β: Its role in normal and Alzheimer’s disease states. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Strooper, B. Loss-of-function presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease: Talking Point on the role of presenilin mutations in Alzheimer disease. Embo Rep. 2007, 8, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, J.; Selkoe, D.J. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, S.; Gries, M.; Christmann, A.; Schäfer, K.-H. Using multielectrode arrays to investigate neurodegenerative effects of the amyloid-beta peptide. Bioelectron. Med. 2021, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Ma, L.; Wei, W.; Li, Z.; Chang, S.; Wen, J.; Sun, J.; Li, H. Role of Aβ in Alzheimer’s-related synaptic dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 964075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J.P.; Stavenhagen, J.B.; Christensen, S.; Kartberg, F.; Glennie, M.J.; Teeling, J.L. Comparing the efficacy and neuroinflammatory potential of three anti-abeta antibodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Schultz, N.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Blennow, K.; Gouras, G.K.; Zetterberg, H.; Hansson, O. Cerebral Aβ deposition precedes reduced cerebrospinal fluid and serum Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios in the AppNL−F/NL−F knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Montoliu-Gaya, L.; Benedet, A.L.; Vrillon, A.; Dumurgier, J.; Cognat, E.; Brum, W.S.; Rahmouni, N.; Stevenson, J.; Servaes, S.; et al. CSF p-tau205: A biomarker of tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 147, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, P.; Hu, L.; Huang, Y.; Guo, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lai, L.; Xue, A.; et al. Exposure to PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS induces Alzheimer’s disease-like neuropathology in cerebral organoids. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 363, 125098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, W.K.; Mungenast, A.E.; Lin, Y.T.; Ko, T.; Abdurrob, F.; Seo, J.; Tsai, L.H. Self-Organizing 3D Human Neural Tissue Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Recapitulate Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotypes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, S. Modelling neurodegenerative disease using brain organoids. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 111, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penney, J.; Ralvenius, W.T.; Tsai, L.-H. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease with iPSC-derived brain cells. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D.M.; Rouleau, N.; Parker, R.N.; Walsh, K.G.; Gehrke, L.; Kaplan, D.L. A 3D human brain–like tissue model of herpes-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, J.; Yu, Y.; Pei, G. Chimeric cerebral organoids reveal the essentials of neuronal and astrocytic APOE4 for Alzheimer’s tau pathology. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.E.; Yu, J.; Shin, H.-M. Exploring the neurodegenerative potential of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances through an adverse outcome pathway network. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Meek, C.J.; McLean, J.L.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Rochet, J.-C.; Liu, F.; Xu, R. Alzheimer’s disease patient brain extracts induce multiple pathologies in novel vascularized neuroimmune organoids for disease modeling and drug discovery. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 4558–4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcourt, N.; Pouget, A.-M.; Grivaud, A.; Nogueira, L.; Larvor, F.; Marchand, P.; Schmidt, E.; Le Bizec, B. First Observations of a Potential Association Between Accumulation of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Central Nervous System and Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2024, 79, glad208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Y.; Rood, J.; Liang, L.; Qi, L.; Bray, G.A.; DeJonge, L.; Coull, B.; Grandjean, P.; et al. Associations of Perfluoroalkyl substances with blood lipids and Apolipoproteins in lipoprotein subspecies: The POUNDS-lost study. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deda, O.; Adams, S.; Tsolaki, M.; Lioupi, A.; Tsolaki, A.; Theodoridis, G.; Wilson, I.; Plumb, R.; Gika, H. UHPLC-MS/MS analysis of PFAS in the serum of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment and controls: A preliminary study. J. Chromatogr. B 2025, 1266, 124738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Harlow, S.D.; Randolph, J.F., Jr.; Loch-Caruso, R.; Park, S.K. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and their effects on the ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 724–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, X.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, J.; Tan, W.; Wu, K. Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) exposures interfere with behaviors and transcription of genes on nervous and muscle system in zebrafish embryos. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, L.M.; Reinhardt, L.; Reinhardt, P.; Glatza, M.; Monzel, A.S.; Stanslowsky, N.; Rosato-Siri, M.D.; Zanon, A.; Antony, P.M.; Bellmann, J.; et al. Modeling Parkinson’s disease in midbrain-like organoids. npj Park. Dis. 2019, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Cai, H.; Ao, Z.; Gu, L.; Li, X.; Niu, V.C.; Bondesson, M.; Gu, M.; Mackie, K.; Guo, F. Engineering human midbrain organoid microphysiological systems to model prenatal PFOS exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.-H.N.; Huang, C.-S.; Chuang, H.-H.; Lai, H.-J.; Yang, C.-K.; Yang, Y.-C.; Kuo, C.-C. An electrophysiological perspective on Parkinson’s disease: Symptomatic pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpa, K.; Saraiva, C.; Lopez-Pigozzi, D.; Gomez-Giro, G.; Gabassi, E.; Spitz, S.; Brandauer, K.; Gatica, J.E.R.; Antony, P.; Robertson, G.; et al. Modeling early phenotypes of Parkinson’s disease by age-induced midbrain-striatum assembloids. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaivade, A.; Erngren, I.; Carlsson, H.; Freyhult, E.; Khoonsari, P.E.; Noui, Y.; Al-Grety, A.; Åkerfeldt, T.; Spjuth, O.; Gallo, V.; et al. Associations of PFAS and OH-PCBs with risk of multiple sclerosis onset and disability worsening. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanzi, A.; Iannoto, G.; Rossi, B.; Zenaro, E.; Constantin, G. In vitro Models of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiani, F.; Pedrini, E.; Taverna, S.; Brambilla, E.; Murtaj, V.; Podini, P.; Ruffini, F.; Butti, E.; Braccia, C.; Andolfo, A.; et al. A glia-enriched stem cell 3D model of the human brain mimics the glial-immune neurodegenerative phenotypes of multiple sclerosis. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviaud, N.; Mehta, T.; Holzman, W.; McDermott, A.; Sadiq, S.A. Impaired Myelination in Multiple Sclerosis Organoids: p21 Links Oligodendrocyte Dysfunction to Disease Subtype. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.L.; Groenendijk, L.; Overdevest, R.; Fowke, T.M.; Annida, R.; Mocellin, O.; de Vries, H.E.; Wevers, N.R. Human BBB-on-a-chip reveals barrier disruption, endothelial inflammation, and T cell migration under neuroinflammatory conditions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraiwa, T.; Yoshii, S.; Kawada, J.; Sugawara, T.; Kawasaki, T.; Shibata, S.; Shindo, T.; Fujimori, K.; Umezawa, A.; Akutsu, H. A human iPSC-Derived myelination model for investigating fetal brain injuries. Regen. Ther. 2025, 29, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, M.; Mozafari, S.; Glatza, M.; Starost, L.; Velychko, S.; Hallmann, A.-L.; Cui, Q.-L.; Schambach, A.; Kim, K.-P.; Bachelin, C.; et al. Rapid and efficient generation of oligodendrocytes from human induced pluripotent stem cells using transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2243–E2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von der Bey, M.; De Cicco, S.; Zach, S.; Hengerer, B.; Ercan-Herbst, E. Three-dimensional co-culture platform of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte lineage cells and neurons for studying myelination. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, A.-N.; Jin, Y.; Kim, S.; Kumar, S.; Shin, H.; Kang, H.-C.; Cho, S.-W. Aligned brain extracellular matrix promotes differentiation and myelination of human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived oligodendrocytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15344–15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, S.; Lawler, S.E.; Qu, Y.; Fadzen, C.M.; Wolfe, J.M.; Regan, M.S.; Pentelute, B.L.; Agar, N.Y.R.; Cho, C.-F. Blood–brain-barrier organoids for investigating the permeability of CNS therapeutics. Nat. Protoc. 2018, 13, 2827–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosulina, L.; Mittag, M.; Geis, H.; Hoffmann, K.; Klyubin, I.; Qi, Y.; Steffen, J.; Friedrichs, D.; Henneberg, N.; Fuhrmann, F.; et al. Hippocampal hyperactivity in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 2128–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nzou, G.; Wicks, R.T.; VanOstrand, N.R.; Mekky, G.A.; Seale, S.A.; El-Taibany, A.; Wicks, E.E.; Nechtman, C.M.; Marrotte, E.J.; Makani, V.S.; et al. Multicellular 3D neurovascular unit model for assessing hypoxia and neuroinflammation induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.C.; Krolewski, R.C.; Moreno, E.L.; Blank, J.; Holton, K.M.; Ahfeldt, T.; Furlong, M.; Yu, Y.; Cockburn, M.; Thompson, L.K.; et al. A pesticide and iPSC dopaminergic neuron screen identifies and classifies Parkinson-relevant pesticides. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amartumur, S.; Nguyen, H.; Huynh, T.; Kim, T.S.; Woo, R.-S.; Oh, E.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, L.P.; Heo, C. Neuropathogenesis-on-chips for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, B.; Manthripragada, A.; Farrer, M.; Cockburn, M.; Rhodes, S.; Bronstein, J. Pesticide exposures from agricultural applications in California and gene-environment interactions in Parkinson’s disease. Epidemiology 2009, 20, S233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrón, T.; Requena, M.; Hernández, A.F.; Alarcón, R. Association between environmental exposure to pesticides and neurodegenerative diseases. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 256, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huat, T.J.; Camats-Perna, J.; Newcombe, E.A.; Valmas, N.; Kitazawa, M.; Medeiros, R. Metal toxicity links to alzheimer’s disease and neuroinflammation. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 1843–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althomali, R.H.; Abbood, M.A.; Saleh, E.A.M.; Djuraeva, L.; Abdullaeva, B.S.; Habash, R.T.; Alhassan, M.S.; Alawady, A.H.R.; Alsaalamy, A.H.; Najafi, M.L. Exposure to heavy metals and neurocognitive function in adults: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Relloso, A.; McGraw, K.E.; Heckbert, S.R.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Schilling, K.; Glabonjat, R.A.; Martinez-Morata, I.; Mayer, M.; Liu, Y.; Wood, A.C.; et al. Urinary metal levels, cognitive test performance, and dementia in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2448286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, S.-A.; Ariafar, S.; Mohammadi, M. Toxic environmental factors and multiple sclerosis: A mechanistic view. Avicenna J. Pharm. Res. 2022, 3, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olloquequi, J.; Díaz-Peña, R.; Verdaguer, E.; Ettcheto, M.; Auladell, C.; Camins, A. From inhalation to neurodegeneration: Air pollution as a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.J.; Tan, H.; Lee, C.Y.; Cho, H. An Air Particulate pollutant induces neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in human brain models. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2101251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.A.; Ukraintseva, S.V.; Duan, H.; Yashin, A.I.; Arbeev, K.G. Traffic-related air pollution and APOE4 can synergistically affect hippocampal volume in older women: New findings from UK Biobank. Front. Dement. 2024, 3, 1402091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.J.; Zarea, K.; Hatamzadeh, N.; Salahshouri, A.; Sharhani, A. Toxic air pollutants and their effect on multiple sclerosis: A review study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 898043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itzhaki, R.F. Overwhelming evidence for a major role for herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD); underwhelming evidence against. Vaccines 2021, 9, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Ke, Q.; Wei, W.; Cui, L.; Wang, Y. Apolipoprotein E and viral infection: Risks and mechanisms. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Ye, X.; Zhang, N.; Ou, M.; Guo, C.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yang, G.; Jing, C. A meta-analysis of interaction between Epstein-Barr virus and HLA-DRB1*1501 on risk of multiple sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Indication | Core Readouts | Distinct Strengths | Key Limitations | Genetic Background | Other Risk Factor(s) | PFAS Exposure | Representative Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral organoids (human iPSC-derived) | AD | Aβ42/40, p-tau (e.g., p-tau181/217), lipidomics (ceramides), synaptic/network activity | Human genetics; spontaneous AD-like phenotypes; compatible with chronic PFAS exposure | Limited vascularization and microglia; maturation variability across protocols | APOE ε3/ε4; familial APP/PSEN1/PSEN2; isogenic WT controls | pesticides; heavy metals; persistent organic pollutants (POPs; PCBs, dioxins); fine/ultrafine air pollution | Yes—PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS ([31]) | [31,33] |

| Vascularized neuroimmune cerebral organoids | AD | Plaque-/tangle-like pathology, microglial activation, synapse loss, network impairments; rescue by therapeutics | Integrates vasculature + immune components; reproduces multiple AD hallmarks | Protocol complexity; exposure paradigms still consolidating | WT hiPSC backgrounds; optionally AD-risk (e.g., APOE ε4) lines | fine/ultrafine air pollution; metal mixtures; POPs; viral antigens/neurotropic viruses | Not reported in cited refs | [39] |

| Chimeric cerebral organoids mixing APOE ε3/ε4 cells | AD | Astrocytic lipid dysregulation, neuronal Aβ increase, robust tau pathology when both lineages carry APOE ε4 | Dissects cell-type–specific APOE ε4 contributions; human genetic context; aligns with lipid–amyloid–tau axis | Batch variability; requires careful cell-mixing ratios; limited vasculature unless engineered | APOE ε3 vs. APOE ε4 mixed chimeras; isogenic backgrounds | heavy metals; air pollution; pesticides; POPs (for APOE–environment interactions) | Not reported in cited refs | [36] |

| Isogenic CRISPR-edited AD organoids (e.g., APOE ε4 knock-in; PSEN1/2 familial mutations) | AD | Genotype-controlled Aβ42/40 shifts, p-tau species, synaptic and network phenotypes; multi-omics contrasts | Clean G × E contrasts with isogenic backgrounds; mechanistic attribution to single alleles | Editing/clone variability; maturation time and batch effects; rigorous QC of edits/off-targets required | APOE ε4; PSEN1/2; APP (Swedish; KM670/671NL); isogenic WT controls | pesticides; heavy metals; air pollution; POPs; viral antigens (for allele-specific G × E studies) | Not reported in cited refs | [32,34] |

| 3D human brain-like tissue model triggering AD-like pathology via viral challenge | AD | Aβ accumulation, neuronal loss; scaffold-based 3D readouts with immunostaining and functional assays | Demonstrates environmental/triggered induction of AD-like features in human 3D tissue | Model depends on specific triggers; not yet standardized for PFAS exposures | Typically WT donor lines | viral antigens/infections (HSV-1, SARS-CoV-2 surrogates); virus + pollutant co-exposures | Not reported in cited refs | [35] |

| Coupled BBB → cerebral organoid microphysiological systems (two-compartment perfusion) | AD (exposure interface) | TEER, PFAS partitioning/translocation, endothelial–astrocyte crosstalk, downstream neuronal/glial responses | Physiologic delivery under flow; quantitative mass-balance of exposure; barrier injury readouts | Device material adsorption; fluidic complexity; multicomponent QA needed for dose verification | Barrier: generic hiPSC endothelium; Parenchyma: organoid genetics as specified (e.g., APOE ε4, PSEN1) | soluble air-pollution components; heavy metals; pesticides; POPs; circulating viral antigens | Not reported in cited refs | [57] |

| BBB organoids/BBB-on-a-chip | Cross-disease exposure interface | TEER, permeability/transport, efflux/transporter function, cytokines under shear | Human barrier biology; mass-balance dosing verification; physiological shear and flow | Requires materials disclosure/adsorption control; neurovascular-immune complexity limited unless co-cultured | Generic hiPSC lines or hCMEC-like endothelium; isogenic NVU co-cultures optional | air pollution (BBB-focused effects); heavy metals; pesticides; small organic toxicants; viral antigens. | Not reported in cited refs (platform suited for PFAS perfusion) | [52] |

| Multicellular 3D neurovascular-unit organoids (NVU-like) | Cross-disease neurovascular interface (hypoxia/neuroinflammation/BBB dysfunction; relevant to MS, stroke and neurodegeneration) | Macromolecular permeability (albumin, IgG, FITC–dextran), tight-junction and adherens markers (ZO-1, occludin, claudin-5, VE-cadherin), BBB transporters (e.g., MDR-1, AQP4, GLUT-1), basement membrane proteins (fibronectin, laminin, collagen IV), oxidative stress and ATP levels, inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MCP-1) | Fully human multicellular NVU spheroids integrating brain microvascular endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes and neurons; recapitulate hypoxia- and cytokine-induced BBB breakdown, oxidative stress and cytokine “storms”; demonstrated suitability for testing anti-inflammatory/antioxidant compounds and conceptually well suited to evaluate environmental toxicants | Static organoid format without defined luminal/abluminal perfusion or physiological shear; diffusion-limited exposure gradients and size heterogeneity; no adaptive immune cells (T/B lymphocytes); original implementation uses generic donor cells rather than patient-specific or isogenic lines; environmental chemicals (including PFAS) not yet tested | Human brain microvascular endothelial cells combined with human pericytes, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes and neurons; generic human donor backgrounds (not isogenic in the original study) | heavy metals; air pollution (PM2.5, ultrafine particles); POPs; viral infections (neurovascular/MS-relevant) | Not reported in cited refs (platform technically suited for PFAS perfusion or static exposure, including under hypoxic/inflammatory conditions) | [59] |

| Glia-enriched human brain organoids (patient iPSC) | MS | Oligodendrocyte maturation (MBP/MAG/PLP), myelination deficits, glial-immune phenotypes | Human background; direct readouts of oligodendrocyte dysfunction | Reduced neuronal complexity; immune system not complete | Patient-derived (e.g., RRMS/SPMS) and matched controls | heavy metals; pesticides; POPs; particulate air pollution; viral/inflammatory MS triggers (e.g., EBV mimetics) | Not reported in cited refs | [50,51] |

| Human iPSC myelination co-cultures/microfluidic myelination chips | MS | De novo myelin formation (MBP + sheaths), sheath length/number; injury/repair assays | Quantifiable human myelination endpoints; suited for remyelination screens | Technically demanding; typically lacks full immune context | WT donor lines; disease-specific (e.g., PMD/MLC) lines in some studies; isogenic edits possible | heavy metals; pesticides; POPs; air pollution; viral/inflammatory cues impairing myelin repair | Not reported in cited refs | [54,55,56] |

| Midbrain organoid microphysiological system (perfusion chip) | PD | TH+ neuron viability, neurite outgrowth, MEA activity, scRNA-seq inflammatory signatures | Dopaminergic specificity; controlled flow and exposure; quantitative functional endpoints | Short feasible exposure windows; simplified niche; limited long-range connectivity | LRRK2 (e.g., p.G2019S) or WT; optional SNCA overexpression | PD-linked pesticides (paraquat, rotenone, etc.); manganese and other dopaminergic metals; combustion-derived particles | Yes—PFOS ([46]) | [46] |

| Nigrostriatal assembloids (midbrain–striatum; MISCO variants) | PD | DA axonal projections, synaptogenesis, catecholamine release, α-syn propagation | Models’ long-range connectivity missing in single-region organoids | Assembly adds variability; limited throughput and standardization | Age-induced in WT lines; PD-mutant variants possible | PD-linked pesticides; manganese and related metals; air-pollution-derived toxicants driving nigrostriatal axonopathy | Not reported in cited refs | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rotondo, D.; Lagostena, L.; Magnelli, V.; Dondero, F. Advanced Cellular Models for Neurodegenerative Diseases and PFAS-Related Environmental Risks. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040125

Rotondo D, Lagostena L, Magnelli V, Dondero F. Advanced Cellular Models for Neurodegenerative Diseases and PFAS-Related Environmental Risks. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040125

Chicago/Turabian StyleRotondo, Davide, Laura Lagostena, Valeria Magnelli, and Francesco Dondero. 2025. "Advanced Cellular Models for Neurodegenerative Diseases and PFAS-Related Environmental Risks" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040125

APA StyleRotondo, D., Lagostena, L., Magnelli, V., & Dondero, F. (2025). Advanced Cellular Models for Neurodegenerative Diseases and PFAS-Related Environmental Risks. NeuroSci, 6(4), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040125