Where Is the Oxygen? The Mirage of Non-Oxidative Glucose Consumption During Brain Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Brief History of the Active Anaerobic Brain

3. A Brief History of the Active Aerobic Brain

4. The Brain on Oxygen

5. To Breathe or Not to Breathe?

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schurr, A.; West, C.A.; Rigor, B.M. Lactate-supported synaptic function in the rat hippocampal slice preparation. Science 1988, 240, 1326–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, P.T.; Raichle, M.E.; Mintun, M.A.; Dence, C. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science 1988, 241, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerin, L.; Magistretti, P.J. Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis: A mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 10625–10629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurr, A. The feud over lactate and its role in brain energy metabolism: An unnecessary burden on research and the scientists who practice it. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienel, G.A.; Rothman, D.L.; Mangia, S. A bird’s-eye view of glycolytic upregulation in activated brain: The major fate of lactate is release from activated tissue, not shuttling to nearby neurons. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, J.P.; Alberini, C.M.; Almeida, A.; Barros, L.F.; Bonvento, G.; Bouzier-Sore, A.K.; Dringen, R.; Hardingham, G.E.; Hirrlinger, J.; Magistretti, P.J.; et al. Embracing the modern biochemistry of brain metabolism. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienel, G.A.; Rothman, D.L.; Mangia, S. Comment on the Editorial “Embracing the Modern Biochemistry of Brain Metabolism”. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.V.; Aldana, B.I.; Bak, L.K.; Behar, K.L.; Borges, K.; Carruthers, A.; Cumming, P.; Derouiche, A.; Díaz-García, C.M.; Drew, K.L.; et al. Embracing Scientific Debate in Brain Metabolism. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, J.P.; Magistretti, P.J. The neuron–astrocyte metabolic unit as a cornerstone of brain energy metabolism in health and disease. Nat. Metab. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Schurr, A. Glycolysis paradigm shift dictates a reevaluation of glucose and oxygen metabolic rates of activated neural tissue. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurr, A.; Passarella, S. Aerobic glycolysis: A DeOxymoron of (neuro) biology. Metabolites 2022, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurr, A. How the ‘aerobic/anaerobic glycolysis’ meme formed a ‘habit of mind’ which impedes progress in the field of brain energy metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

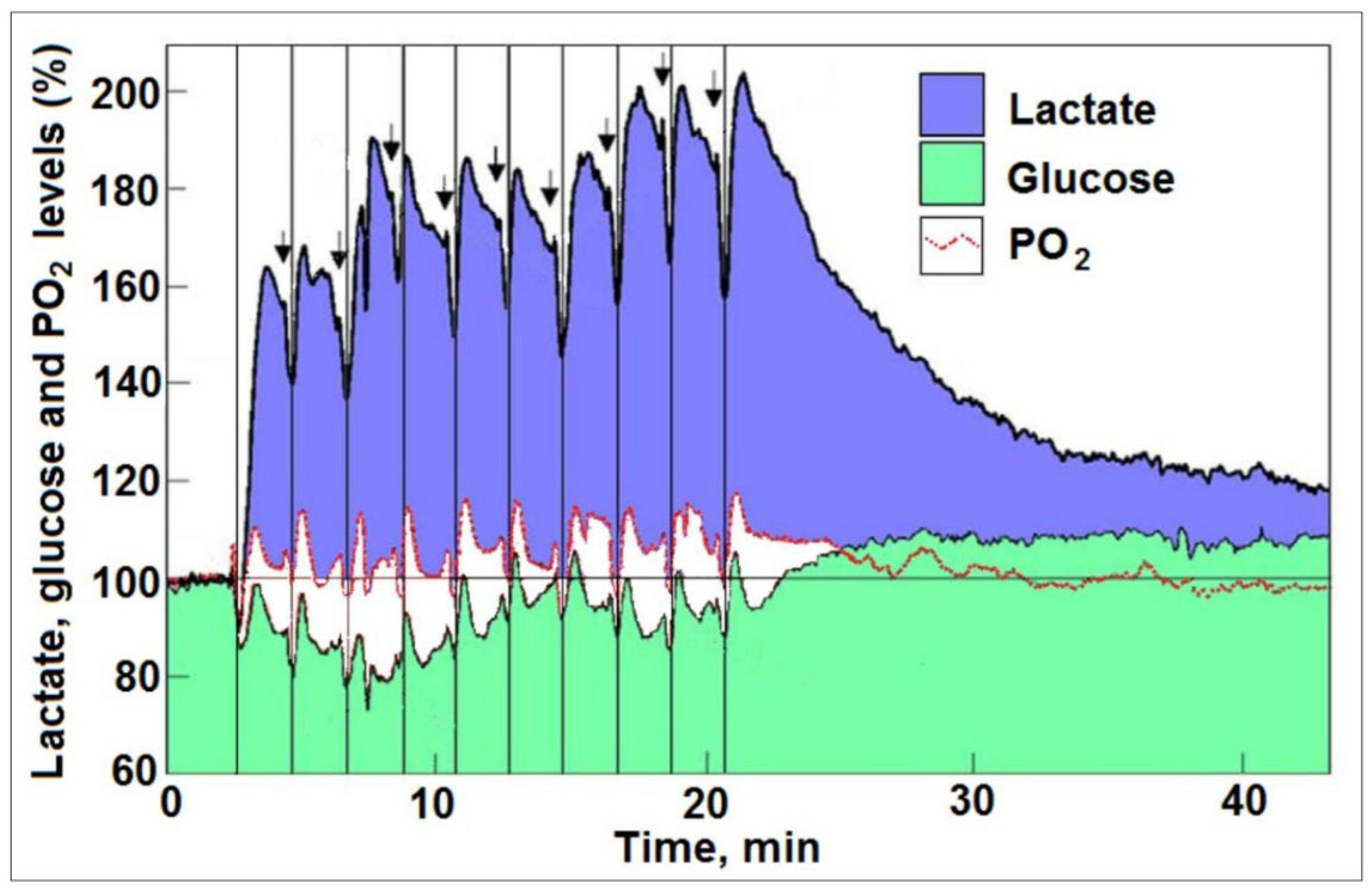

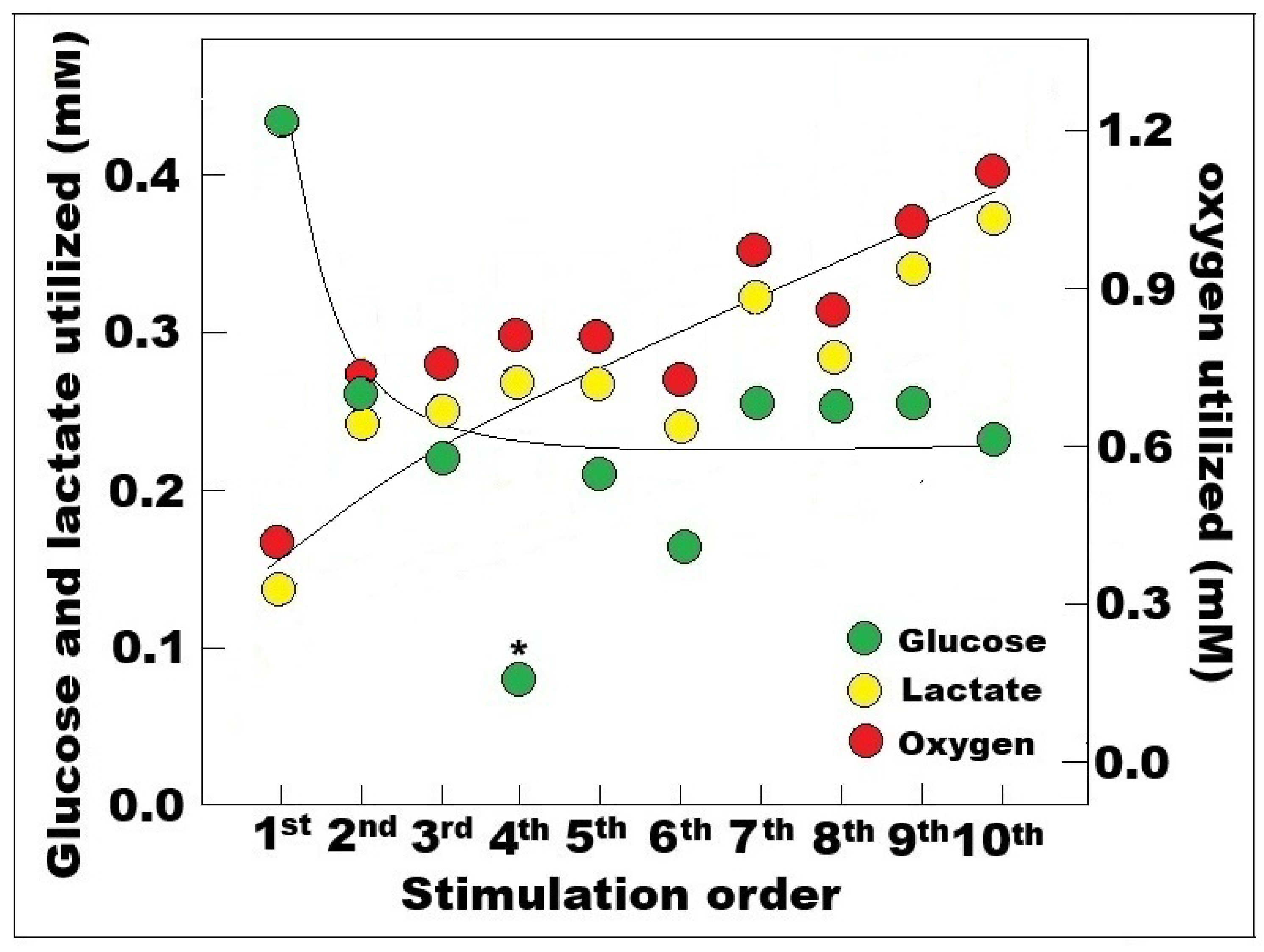

- Hu, Y.; Wilson, G.S. A temporary local energy pool coupled to neuronal activity: Fluctuations of extracellular lactate levels in rat brain monitored with rapid-response enzyme-based sensor. J. Neurochem. 1997, 69, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, A.M.; Scholkmann, F. The Significance of Lipids for the Absorption and Release of Oxygen in Biological Organisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1438, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

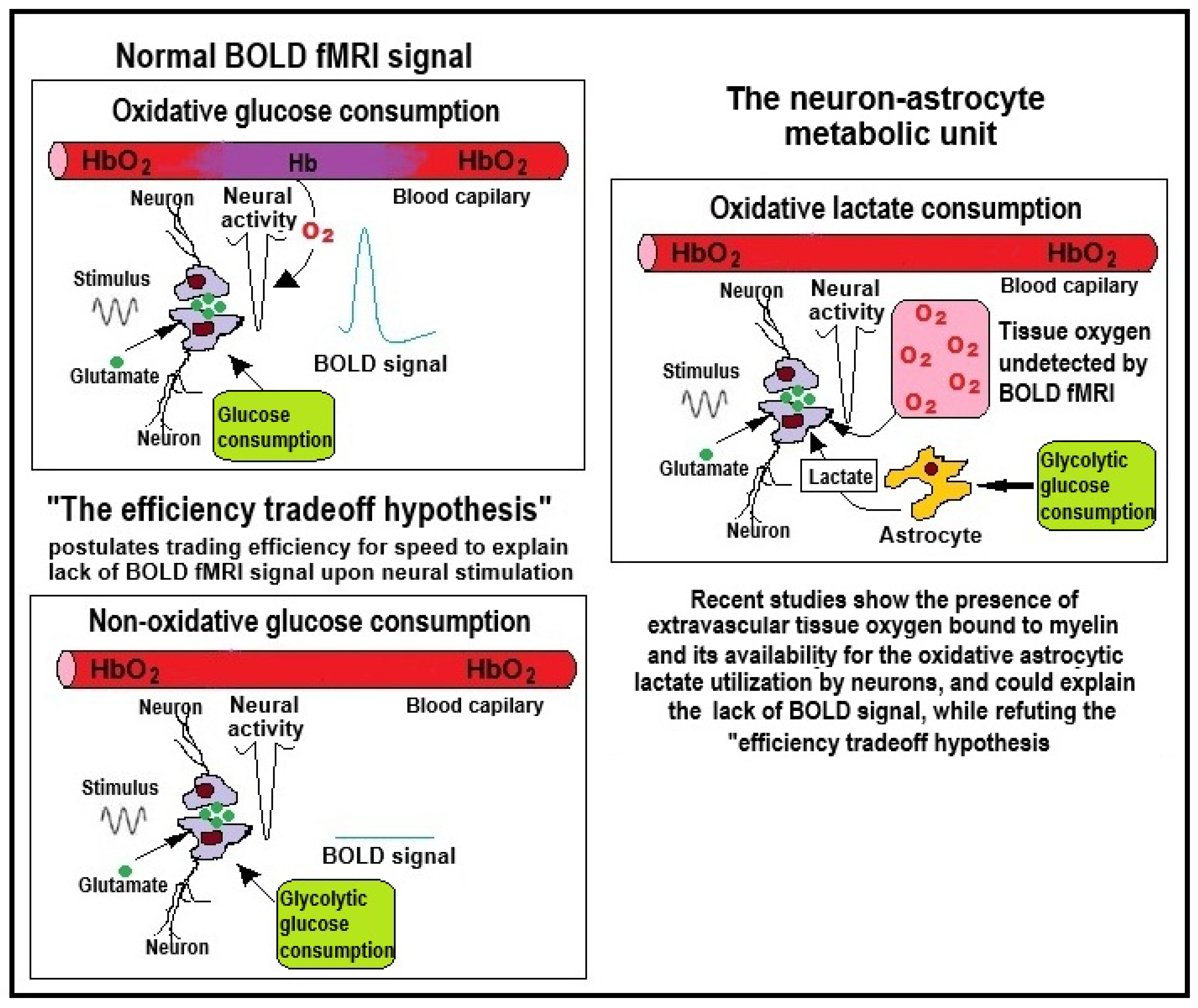

- Vervust, W.; Safaei, S.; Witschas, K.; Leybaert, L. Myelin sheaths can act as compact temporary oxygen storage units as modeled by an electrical RC circuit model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2422437122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, J.; Rothman, D.; Novotny, E.; Petroff, O.; Kuwabara, T.; Avison, M.; Howseman, A.; Hanstock, C.; Shulman, R. Lactate rise detected by 1H NMR in human visual cortex during physiologic stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 5829–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichle, M.E. The metabolic requirements of functional activity in the human brain: A Positron emission tomography study. In Fuel Homeostasis and the Nervous System; Vranic, M., Efendic, S., Hollenberg, C.H., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; Volume 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellows, L.K.; Boutelle, M.G.; Fillenz, M. Physiological stimulation increases nonoxidative glucose metabolism in the brain of the freely moving rat. J. Neurochem. 1993, 60, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, R.G.; Blamire, A.M.; Rothman, D.L.; McCarthy, G. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy ofhuman brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 3127–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.G.; Holmes, B.E. Contributions to the Study of Brain Metabolism: Carbohydrate Metabolism. Biochem. J. 1925, 19, 836–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.G.; Holmes, B.E. Contributions to the study of brain metabolism: Carbohydrate metabolism relationship of glycogen and lactic acid. Biochem. J. 1926, 20, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, B.E.; Holmes, E.G. Contributions to the Study of Brain Metabolism. IV: Carbohydrate Metabolism of the Brain Tissue of Depancreatised Cats. Biochem. J. 1927, 21, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashford, C.A.; Holmes, E.G. Contributions to the study of brain metabolism: Rôle of phosphates in lactic acid production. Biochem. J. 1929, 23, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.G.; Ashford, C.A. Lactic acid oxidation in brain with reference to the “Meyerhof cycle”. Biochem. J. 1930, 24, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.G. Oxidations in central and peripheral nervous tissue. Biochem. J. 1930, 24, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.G. The relation between carbohydrate metabolism and the function of the grey matter of the central nervous system. Biochem. J. 1933, 27, 523–536. [Google Scholar]

- Schurr, A. Lactate: The ultimate cerebral oxidative energy substrate? J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2006, 26, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kety, S.S.; Schmidt, C.F. The nitrous oxide method for the quantitative determination of cerebral blood flow in man: Theory, procedure and normal values. J. Clin. Investig. 1948, 27, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kety, S.S. The general metabolism of the brain in vivo. In Metabolism of the Nervous System; Richter, D., Ed.; Pergamon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA; Paris, France; Los Angeles, LA, USA, 1957; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, S.; Lee, T.M.; Kay, A.R.; Tank, D.W. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 9868–9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullinger, K.J.; Mayhew, S.D.; Bagshaw, A.P.; Bowtell, R.; Francis, S.T. Evidence that the negative BOLD response is neuronal in origin: A simultaneous EEG–BOLD–CBF study in humans. Neuroimage 2014, 94, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schridde, U.; Khubchandani, M.; Motelow, J.E.; Sanganahalli, B.G.; Hyder, F.; Blumenfeld, H. Negative BOLD with large increases in neuronal activity. Cereb. Cortex 2008, 18, 1814–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiernman, L.J.; Grill, F.; Hahn, A.; Rischka, L.; Lanzenberger, R.; Lundmark, V.P.; Riklund, K.; Axelsson, J.; Rieckmann, A. Dissociations between glucose metabolism and blood oxygenation in the human default mode network revealed by simultaneous PET-fMRI. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021913118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, W.J.; Li, J.M.; Snyder, A.Z.; Raichle, M.E.; Snyder, L.H. Oxygen level and LFP in task-positive and task-negative areas: Bridging BOLD fMRI and electrophysiology. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ances, B.M.; Leontiev, O.; Perthen, J.E.; Liang, C.; Lansing, A.E.; Buxton, R.B. Regional differences in the coupling of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism changes in response to activation: Implications for BOLD-fMRI. Neuroimage 2008, 39, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angenstein, F. The role of ongoing neuronal activity for baseline and stimulus-induced BOLD signals in the rat hippocampus. Neuroimage 2019, 202, 116082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, R.B.; Frank, L.R. A model of the coupling between cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism during neural stimulation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1997, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjedde, A. The relation between brain function and cerebral blood flow and metabolism. In Cerebrovascular Disease; Batjer, H.H., Ed.; Lippincott-Raven: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, F.; Shulman, R.G.; Rothman, D.L. A model for the regulation of cerebral oxygen delivery. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 85, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theriault, J.E.; Shaffer, C.; Dienel, G.A.; Sander, C.Y.; Hooker, J.M.; Dickerson, B.C.; Feldman Barrett, L.; Quigley, K.S. A functional account of stimulation-based aerobic glycolysis and its role in interpreting BOLD signal intensity increases in neuroimaging experiments. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 153, 105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienel, G.A. Astrocytic energetics during excitatory neurotransmission: What are contributions of glutamate oxidation and glycolysis? Neurochem. Internt 2013, 63, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, N.; Kidd, G.J.; Mahad, D.; Kiryu-Seo, S.; Avishai, A.; Komuro, H.; Trapp, B.D. Myelination and axonal electrical activity modulate the distribution and motility of mitochondria at CNS nodes of Ranvier. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 7249–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perge, J.A.; Koch, K.; Miller, R.; Sterling, P.; Balasubramanian, V. How the optic nerve allocates space, energy capacity, and information. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 7917–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacci, M.K.; Bartlett, C.A.; Huynh, M.; Kilburn, M.R.; Dunlop, S.A.; Fitzgerald, M. Three dimensional electron microscopy reveals changing axonal and myelin morphology along normal and partially injured optic nerves. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsatzis, D.G.; Tingas, E.-A.; Sarathy, S.M.; Goussis, D.A.; Jolivet, R.B. Elucidating reaction dynamics in a model of human brain energy metabolism. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernero, A.; Vicario, C.; Medina, J.M. Lactate spares glucose as a metabolic fuel in neurons and astrocytes from primary culture. Neurosci. Res. 1996, 26, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurr, A.; Payne, R.S.; Miller, J.J.; Rigor, B.M. Glia are the main source of lactate utilized by neurons for recovery of function posthypoxia. Brain Res. 1997, 774, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurr, A.; Miller, J.J.; Payne, R.S.; Rigor, B.M. An increase in lactate output by brain tissue serves to meet the energy needs of glutamate-activated neurons. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, E.; Tang, J.M.; Ludvig, N.; Bergold, P.J. Elevated lactate suppresses neuronal firing in vivo and inhibits glucose metabolism in hippocampal slice cultures. Brain Res. 2006, 1117, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurr, A.; Gozal, E. Aerobic production and utilization of lactate satisfy increased energy demands upon neuronal activation in hippocampal slices and provide neuroprotection against oxidative stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 2, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarczyluk, M.A.; Nagel, D.A.; O’Neil, J.D.; Parri, H.R.; Tse, E.H.; Coleman, M.D.; Hill, E.J. Functional astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle in a human stem cell-derived neuronal network. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Fernandes, E.; Barbosa, R.M.; Laranjinha, J.; Ledo, A. Astrocytic aerobic glycolysis provides lactate to support neuronal oxidative metabolism in the hippocampus. Biofactors 2023, 49, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthayakumar, B.; Soliman, H.; Chen, A.P.; Bragagnolo, N.; Cappelletto, N.I.; Endre, R.; Perks, W.J.; Ma, N.; Heyn, C.; Keshari, K.R.; et al. Evidence of 13C-lactate oxidation in the human brain from hyperpolarized 13C-MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2024, 91, 2162–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Soliman, H.; Geraghty, B.J.; Chen, A.P.; Connelly, K.A.; Endre, R.; Perks, W.J.; Heyn, C.; Black, S.; Cunningham, C.H. Lactate topography of the human brain using hyperpolarized 13C-MRI. Neuroimage 2020, 204, 116202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koep, J.L.; Duffy, J.S.; Carr, J.M.J.R.; Brewster, M.L.; Bird, J.D.; Monteleone, J.A.; Monaghan, T.D.R.; Islam, H.; Steele, A.R.; Howe, C.A.; et al. Preferential lactate metabolism in the human brain during exogenous and endogenous hyperlactataemia. J. Physiol. 2025, 603, 6783–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söder, L.; Baeza-Lehnert, F.; Khodaie, B.; Elgez, A.; Noack, L.; Lewen, A.; Hallermann, S.; Poschet, G.; Borges, K.; Kann, O. Lactate transport via glial MCT1 and neuronal MCT2 is not required for synchronized synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices supplied with glucose. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, J.V.; McKenna, M.C. Neurons in need: Glucose, but not lactate, is required to support energy-demanding synaptic transmission. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Myeong, J.; Hashemiaghdam, A.; Stunault, M.I.; Zhang, H.; Niu, X.; Laramie, M.A.; Sponagel, J.; Shriver, L.P.; Patti, G.J.; et al. Mitochondrial pyruvate transport regulates presynaptic metabolism and neurotransmission. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangari, J.; Petrelli, F.; Maillot, B.; Martinou, J.C. The multifaceted pyruvate metabolism: Role of the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurr, A. Cerebral glycolysis: A century of persistent misunderstanding and misconception. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarella, S.; Paventi, G.; Pizzuto, R. The mitochondrial L-lactate dehydrogenase affair. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogatzki, M.J.; Ferguson, B.; Goodwin, M.L.; Gladden, L.B. Lactate is always the end product of glycolysis. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Miao, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Mao, S.; Li, M.; Xu, X.; Xia, X.; Wei, K.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, X.; et al. Aerobic glycolysis is the predominant means of glucose metabolism in neuronal somata, which protects against oxidative damage. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.; Bartsch, A.J. Pitfalls in fMRI. Eur. Radiol. 2009, 19, 2689–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zijl, P.C.; Hua, J.; Lu, H. The BOLD post-stimulus undershoot, one of the most debated issues in fMRI. Neuroimage 2012, 62, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, E.M.C. Coupling mechanism and significance of the BOLD signal: A status report. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 37, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schurr, A. Where Is the Oxygen? The Mirage of Non-Oxidative Glucose Consumption During Brain Activity. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040126

Schurr A. Where Is the Oxygen? The Mirage of Non-Oxidative Glucose Consumption During Brain Activity. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040126

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchurr, Avital. 2025. "Where Is the Oxygen? The Mirage of Non-Oxidative Glucose Consumption During Brain Activity" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040126

APA StyleSchurr, A. (2025). Where Is the Oxygen? The Mirage of Non-Oxidative Glucose Consumption During Brain Activity. NeuroSci, 6(4), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040126