Mercury Removal and Antibacterial Performance of A TiO2–APTES Kaolin Composite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

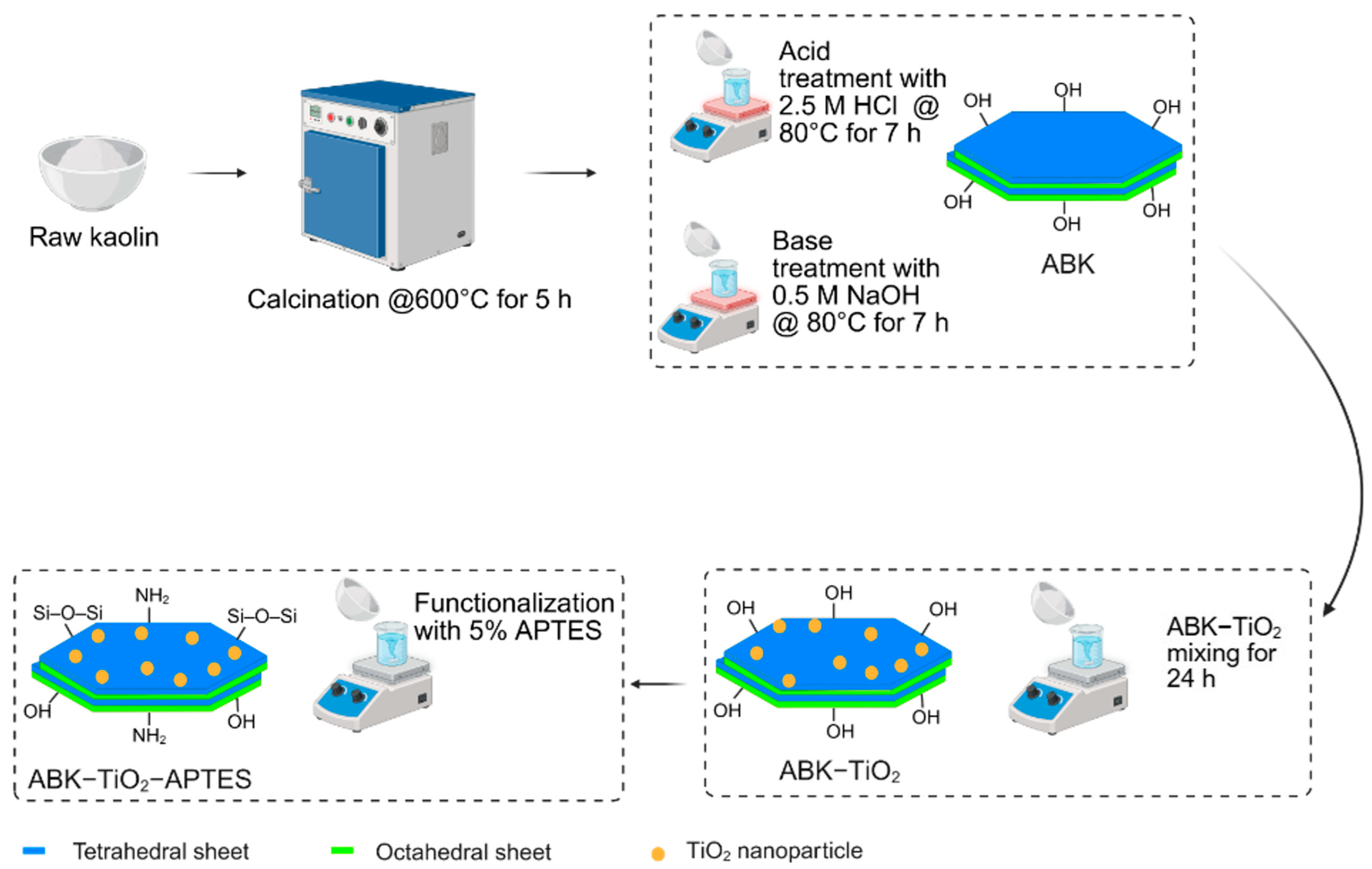

2.2. Material Preparation

2.2.1. Acid–Base Treatment of Kaolin

2.2.2. TiO2 Loading and APTES Grafting on Kaolin

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Adsorption Studies

2.5. Adsorption Modeling

2.6. Desorption and Reuse Studies

2.7. Antibacterial Activity Assay

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

3.1.1. Chemical Composition

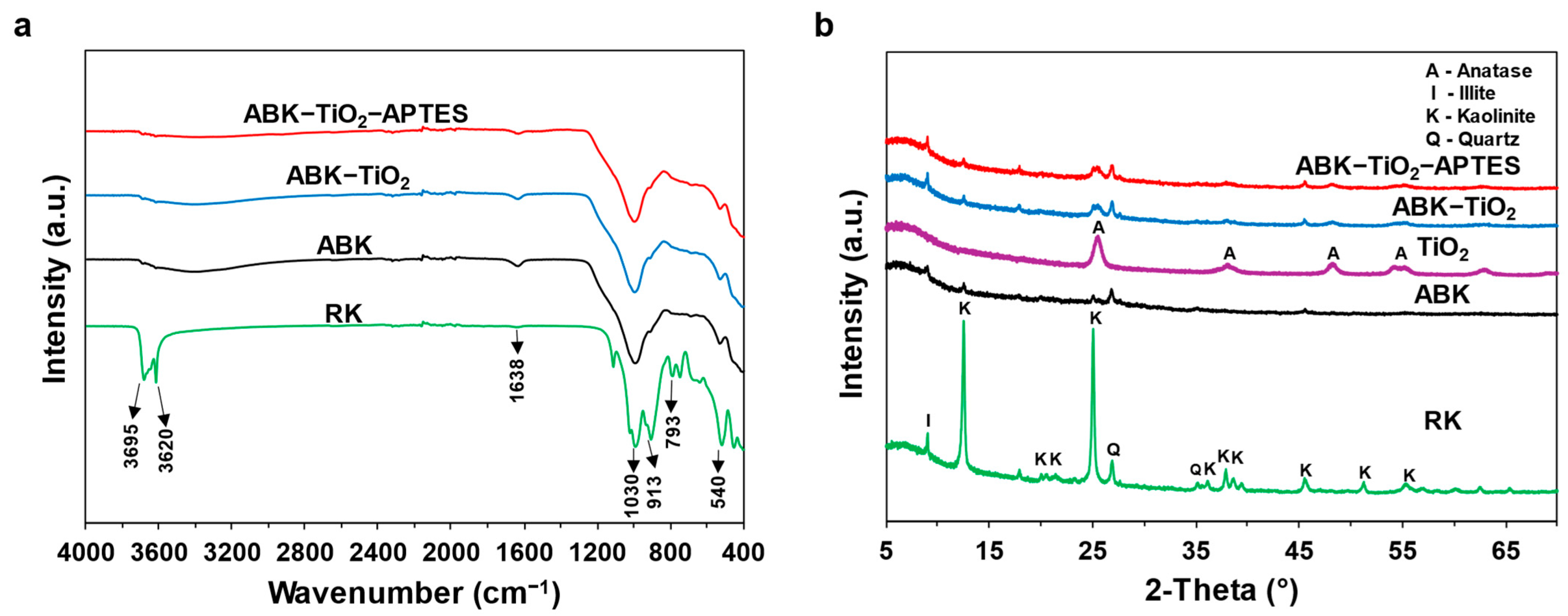

3.1.2. Structural Characterization

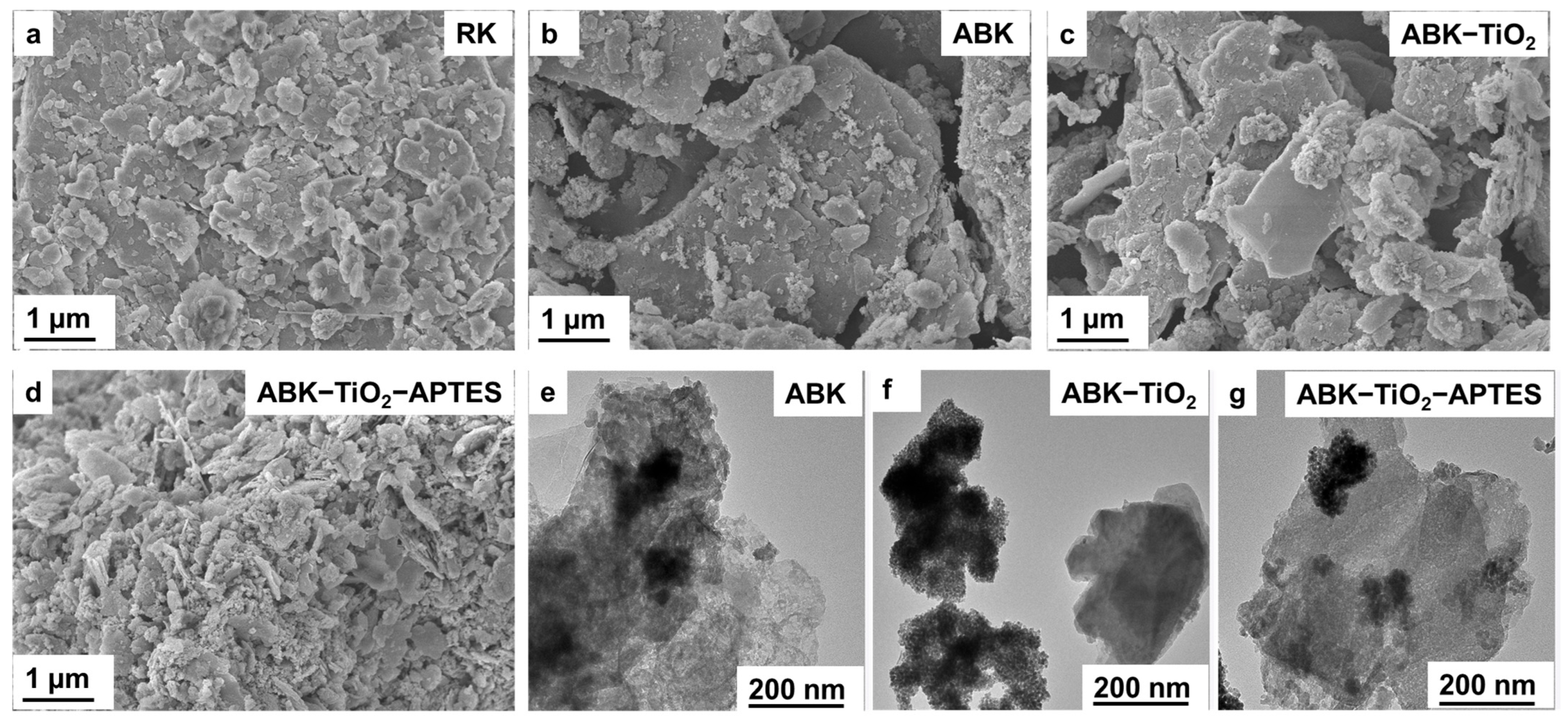

3.1.3. Morphological Characterization

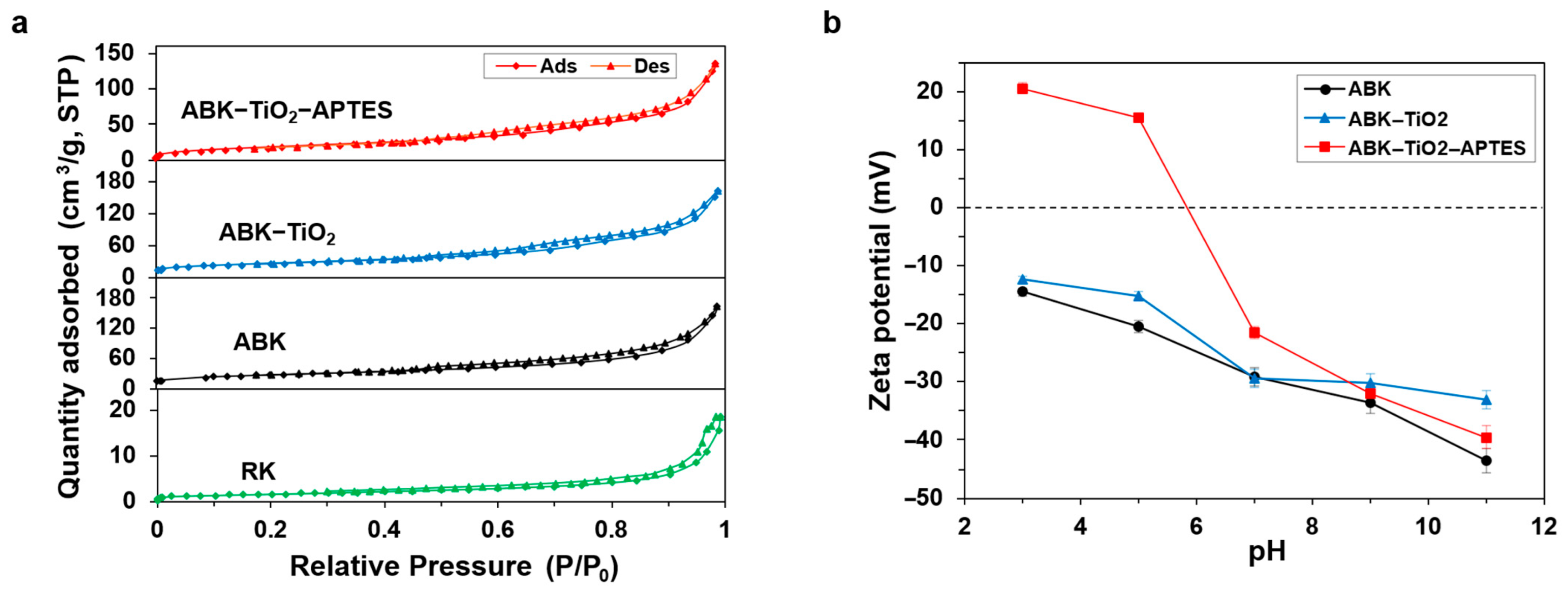

3.1.4. Textural Properties

3.2. Adsorption Studies

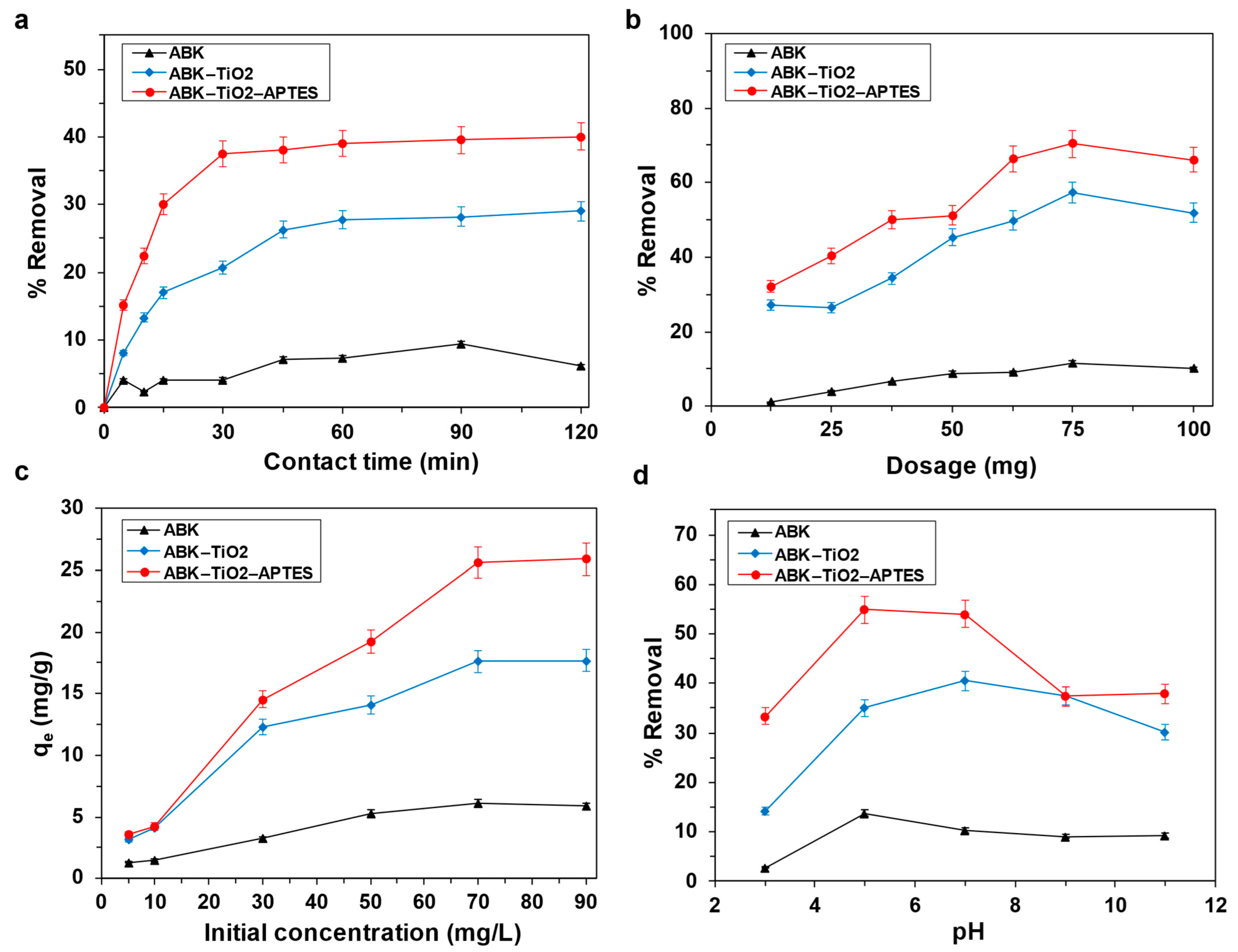

3.2.1. Contact Time

3.2.2. Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

3.2.3. Effect of Initial Mercury Concentration

3.2.4. Effect of Solution pH

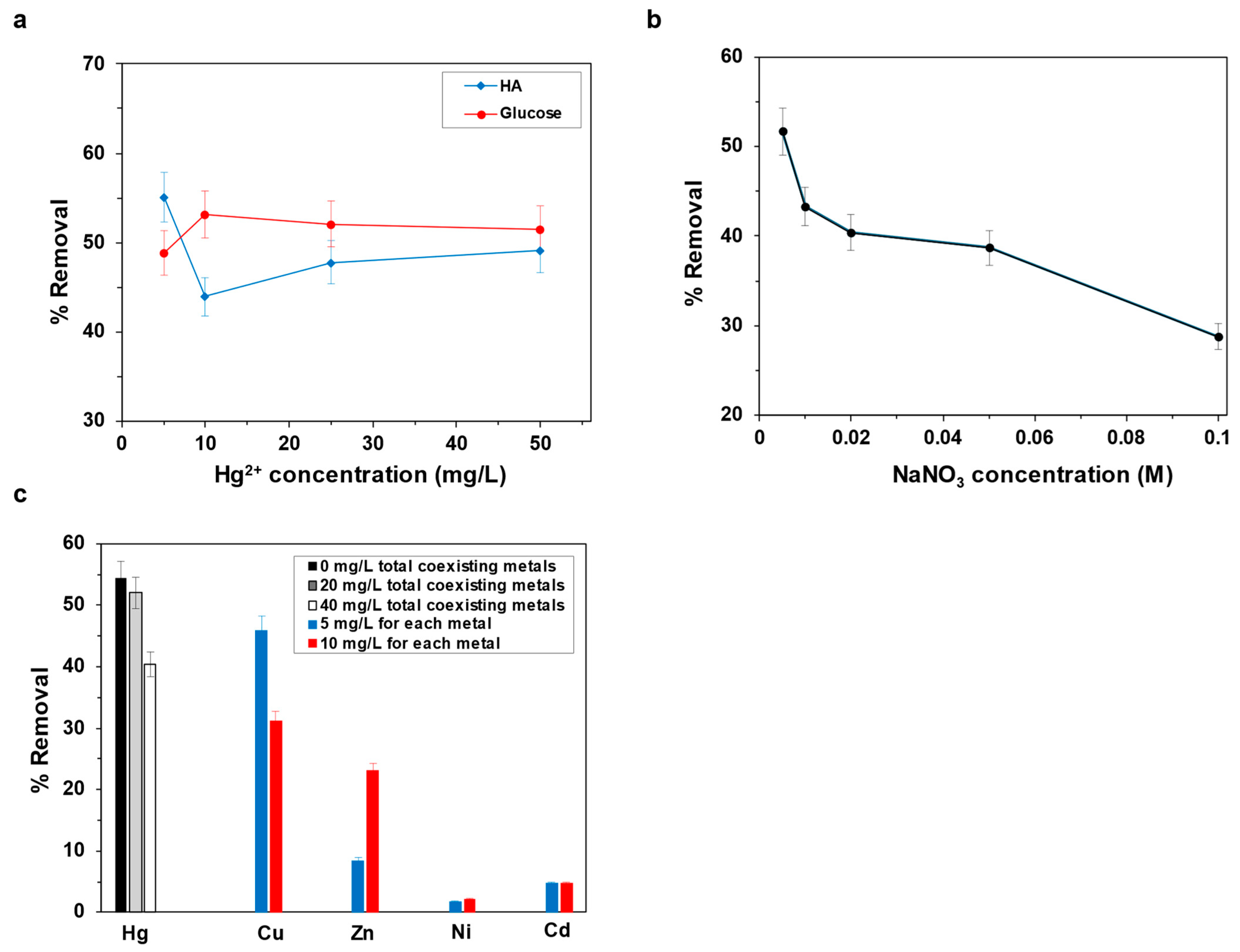

3.3. Effect of Water Matrix Components on Adsorption Efficiency

3.3.1. Effect of Natural Organic Matter

3.3.2. Effect of Ionic Strength

3.3.3. Effect of Coexisting Heavy Metals

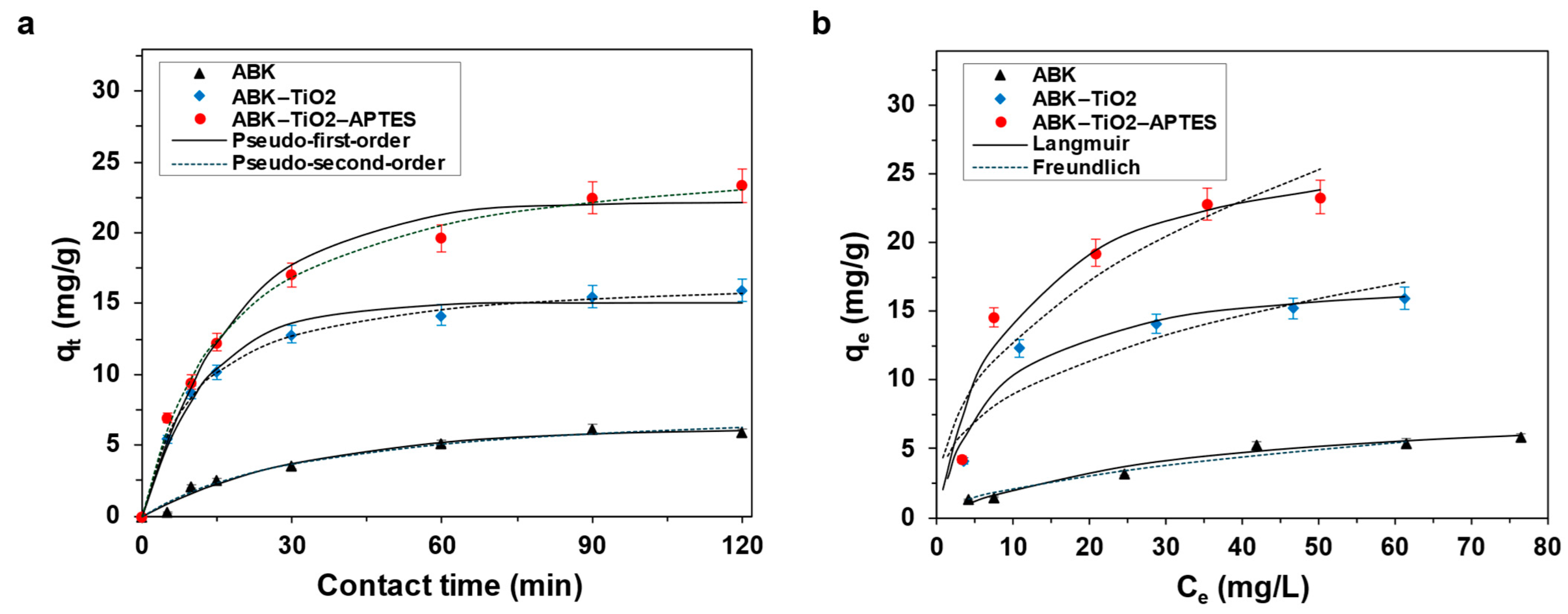

3.4. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherms

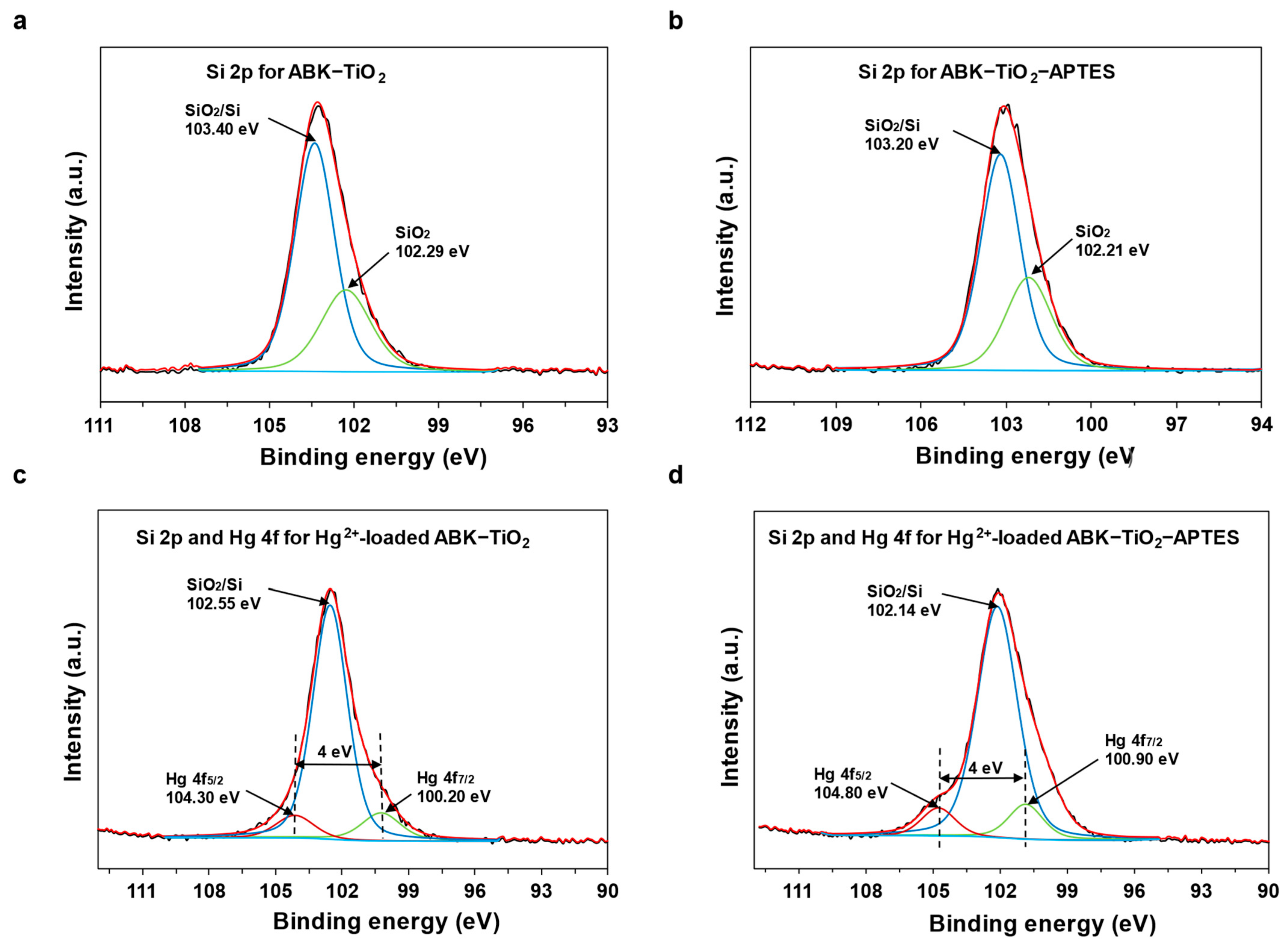

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism

3.6. Desorption and Reuse Studies

3.7. Antibacterial Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanafin, Y.N.; Abduvalov, A.; Kaikanov, M.; Poulopoulos, S.G.; Atabaev, T.S. A Review on WO3 Photocatalysis Used for Wastewater Treatment and Pesticide Degradation. Heliyon 2025, 11, e40788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Hakami, M.; Zacharof, M.-P.; Abu Homod, H.; Alsadun, A. Mercury, Arsenic and Lead Removal by Air Gap Membrane Distillation: Experimental Study. Water 2020, 12, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.B.S.; Costa, J.M.; Santos, G.E.; Sancinetti, G.P.; Rodriguez, R.P. Removal of Metals by Biomass Derived Adsorbent in Its Granular and Powdered Forms: Adsorption Capacity and Kinetics Analysis. Sustain. Chem. 2022, 3, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Quiroz, G.E.; Valencia-Leal, S.A.; Vázquez-Guerrero, A.; Alfaro-Cuevas-Villanueva, R.; Escudero-García, R.; Cortés-Martínez, R. Surfactant-Enhanced Guava Seed Biosorbent for Lead and Cadmium Removal: Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Reusability Insights. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkou, A.K.; Toubanaki, D.K.; Kyzas, G.Z. Detection of Arsenic, Chromium, Cadmium, Lead, and Mercury in Fish: Effects on the Sustainable and Healthy Development of Aquatic Life and Human Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Zhu, G. Highly Efficient Removal of Mercury Ions from Aqueous Solutions by Thiol-Functionalized Graphene Oxide. Water 2023, 15, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dack, K.; Fell, M.; Taylor, C.M.; Havdahl, A.; Lewis, S.J. Prenatal Mercury Exposure and Neurodevelopment up to the Age of 5 Years: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, K.M.; Walker, E.M.; Wu, M.; Gillette, C.; Blough, E.R. Environmental Mercury and Its Toxic Effects. J. Prev. Med. Pub. Health 2014, 47, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahir, F.; Rizwi, S.J.; Haq, S.K.; Khan, R.H. Low Dose Mercury Toxicity and Human Health. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2005, 20, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sultana, K.W.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Mondal, M.; Chandra, I. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Its Impact on Health: Exploring Green Technology for Remediation. Environ. Health Insights 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Yang, B.; Northwood, D.O.; Waters, K.E.; Ma, H. The Deep Removal of Mercury in Contaminated Acid by Colloidal Agglomeration Materials M201. Minerals 2024, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Vogler, R.J.; Abdullah Al Hasnine, S.M.; Hernandez, S.; Malekzadeh, N.; Hoelen, T.P.; Hatakeyama, E.S.; Bhattacharyya, D. Mercury Removal from Wastewater Using Cysteamine Functionalized Membranes. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 22255–22267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.P.; Faria, T.L.; Pereira, E.; Portugal, I.; Lopes, C.B.; Silva, C.M. Mercury Removal from Aqueous Solution Using ETS-4 in the Presence of Cations of Distinct Sizes. Materials 2021, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Da’ana, D.; Abu-Dieyeh, M.; Khraisheh, M. Adsorptive Removal of Mercury from Water by Adsorbents Derived from Date Pits. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Fatima, N.; Naz, E.; Farooqi, Z.U.R.; Bulgariu, L. Treatment Methods for Mercury Removal From Soil and Wastewater. In Mercury Toxicity Mitigation: Sustainable Nexus Approach; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gkika, D.A.; Tolkou, A.K.; Poulopoulos, S.G.; Kalavrouziotis, I.K.; Kyzas, G.Z. Cost-Effectiveness of Regenerated Green Materials for Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Wastewater. Waste Manag. 2025, 204, 114952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teweldebrihan, M.D.; Dinka, M.O. Adsorptive Removal of Hexavalent Chromium from Aqueous Solution Utilizing Activated Carbon Developed from Spathodea Campanulata. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I. The Quest for Active Carbon Adsorbent Substitutes: Inexpensive Adsorbents for Toxic Metal Ions Removal from Wastewater. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2010, 39, 95–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, T.; Yin, D.; Han, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Tian, X. Modified Clay Mineral: A Method for the Remediation of the Mercury-Polluted Paddy Soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 204, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanfire, B.-E.; Bulgariu, D.; Cimpoeşu, N.; Bulgariu, L. Efficient Removal of Toxic Heavy Metals on Kaolinite-Based Clay: Adsorption Characteristics, Mechanism and Applicability Perspectives. Water 2025, 17, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglezakis, V.J.; Kudarova, A.; Guney, A.; Kinayat, N.; Tauanov, Z. Efficient Mercury Removal from Water by Using Modified Natural Zeolites and Comparison to Commercial Adsorbents. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 32, 101017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.M.; Reddy, D.H.K.K.; Venkateswarlu, P.; Seshaiah, K. Removal of Mercury from Aqueous Solutions Using Activated Carbon Prepared from Agricultural By-Product/Waste. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 90, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu, T.O.; Adegoke, H.I.; Odebunmi, E.O.; Shehzad, M.A. Enhancing Adsorption Capacity of a Kaolinite Mineral through Acid Activation and Manual Blending with a 2:1 Clay. Niger. J. Technol. Dev. 2024, 21, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudzielwana, R.; Gitari, M.W.; Ndungu, P. Uptake of As(V) from Groundwater Using Fe-Mn Oxides Modified Kaolin Clay: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Data Modeling. Water 2019, 11, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunkaynak, Y.; Canpolat, M.; Yavuz, Ö. Adsorption of Mercury (II) Ions on Kaolinite from Aqueous Solutions: Isothermal, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Studies. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2024, 43, e14295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Pan, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, L.; Shen, J.; Xia, K.; Guo, Y.; Qu, Z. Removal of Hg2+ with Polypyrrole-Functionalized Fe3O4/Kaolin: Synthesis, Performance and Optimization with Response Surface Methodology. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Shen, S.; Zhang, G.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, X. Efficient Removal of Hg2+ by L-Cysteine and Polypyrrole-Functionalized Magnetic Kaolin: Condition Optimization, Model Fitting and Mechanism. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2022, 48, 4287–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, T.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, R.; Huang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Wu, J. The Application of Mineral Kaolinite for Environment Decontamination: A Review. Catalysts 2023, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Panda, A.K.; Singh, R.K. Preparation and Characterization of Acids and Alkali Treated Kaolin Clay. Bull. Chem. React. Eng. Catal. 2013, 8, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makó, É.; Sarkadi, Z.; Ható, Z.; Kristóf, T. Characterization of Kaolinite-3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane Intercalation Complexes. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 231, 106753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, L.R.; Faria, E.H.d.; Ciuffi, K.J.; Nassar, E.J.; Calefi, P.S.; Vicente, M.A.; Trujillano, R. New Synthesis Strategies for Effective Functionalization of Kaolinite and Saponite with Silylating Agents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 341, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donga, C.; Mishra, S.; Aziz, A.; Ndlovu, L.; Kuvarega, A.; Mishra, A.K. (3-Aminopropyl) Triethoxysilane (APTES) Functionalized Magnetic Nanosilica Graphene Oxide (MGO) Nanocomposite for the Comparative Adsorption of the Heavy Metal (Pb(II), Cd(II) and Ni(II)) Ions from Aqueous Solution. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2021, 32, 2235–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Gao, M. Functional Organoclays for Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Water: A Review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 334, 116143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, Y.; El Ibrahimi, B.; Ahrouch, M.; Kassab, Z.; El Kaim Billah, R.; Coppel, Y.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Abou Oualid, H.; Díaz de León, J.N.; Leiviskä, T.; et al. New Hybrid Adsorbent Based on APTES Functionalized Zeolite W for Lead and Cadmium Ions Removal: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meroufel, B.; Zenasni, M.A. Preparation, Characterization, and Heavy Metal Ion Adsorption Property of APTES-Modified Kaolin: Comparative Study with Original Clay. In Handbook of Environmental Materials Management; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Qian, Y.; Li, Q.; Wei, Z.; Zhai, J. Fast Removal of Hg(II) Ions from Aqueous Solution by Amine-Modified Attapulgite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 72, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, S.; Tijani, J.O.; Ndamitso, M.M.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Shuaib, D.T.; Mohammed, A.K. Adsorptive Removal of Pollutants from Industrial Wastewater Using Mesoporous Kaolin and Kaolin/TiO2 Nanoadsorbents. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2021, 15, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.C.; Saavedra, M.J.; Gomes, I.B.; Simões, M.; Simões, L.C. Current Microbiological Challenges in Drinking Water. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 72, 107614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.V.; Zanetti, M.O.B.; Pitondo-Silva, A.; Stehling, E.G. Aquatic Environments Polluted with Antibiotics and Heavy Metals: A Human Health Hazard. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 5873–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serov, D.A.; Gritsaeva, A.V.; Yanbaev, F.M.; Simakin, A.V.; Gudkov, S.V. Review of Antimicrobial Properties of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicka-Konieczna, P.; Wanag, A.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Izuma, D.S.; Ekiert, E.; Kusiak-Nejman, E.; Terashima, C.; Yasumori, A.; Fujishima, A.; Morawski, A.W. Photocatalytic Inactivation of Co-Culture of E. Coli and S. Epidermidis Using APTES-Modified TiO2. Molecules 2023, 28, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulsalam, A.A.; Pirman, M.; Begenova, D.; Kyzas, G.Z.; Xia, D.; Pham, T.T.; Golman, B.; Poulopoulos, S.G. Thiol Functionalized Kaolin Pellets: Development and Optimization for Mercury Ion Removal from Aqueous Solutions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 277, 107983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. Adsorption of gasbs on glass, mica and platinum. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Über Die Adsorption in Lösungen. Z. Für Phys. Chem. 1907, 57U, 385–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergenbayeva, S.; Bekaliyev, A.; Junissov, A.; Begenova, D.; Pham, T.T.; Poulopoulos, S.G. 4-Nitrophenol Reduction and Antibacterial Activity of Ag-Doped TiO2 Photocatalysts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 4640–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasto, L.; Hellar-Kihampa, H.; Mgani, Q.A.; Lugwisha, E.H.J. Comparative Analysis of Cationic Dye Adsorption Efficiency of Thermally and Chemically Treated Tanzanian Kaolin. Environ Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yan, Z.; Ouyang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Chen, D. Chemically Modified Kaolinite Nanolayers for the Removal of Organic Pollutants. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 157, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunadasa, K.S.P.; Wijekoon, A.S.K.; Manoratne, C.H. TiO2-Kaolinite Composite Photocatalyst for Industrial Organic Waste Decontamination. Next Materials. 2024, 3, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, K.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z. TiO2 Nanoparticles Assembled on Kaolinites with Different Morphologies for Efficient Photocatalytic Performance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanafin, Y.N.; Turpanova, R.; Beisekova, M.; Poulopoulos, S.G. Sewage Sludge Biochar as a Persulfate Activator for Methylene Blue Degradation. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belver, C.; Bañares Muñoz, M.A.; Vicente, M.A. Chemical Activation of a Kaolinite under Acid and Alkaline Conditions. Chem. Mater. 2002, 14, 2033–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Shen, X.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Liang, J. Clay-Based Materials for Heavy Metals Adsorption: Mechanisms, Advancements, and Future Prospects in Environmental Remediation. Crystals 2024, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mouden, A.; Aasli, B.; El Messaoudi, N.; El Guerraf, A.; Miyah, Y.; Erraji, F.Z.; Almehizia, A.A.; Jada, A.; Lacherai, A. Synthesis of 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane-Modified Phoenix dactylifera Date Stone Combined with Natural Clay for Adsorption of Mercury Ions from Aqueous Solution. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, P.; Sun, T.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y. Using Thiol-Functionalized Montmorillonites for Chemically Immobilizing Hg in Contaminated Water and Soil: A Comparative Study of Intercalation and Grafting Functionalization. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 216, 106381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekhar, S.; Ramasamy, D.L.; Srivastava, V.; Asif, M.B.; Sillanpää, M. Understanding the Factors Affecting the Adsorption of Lanthanum Using Different Adsorbents: A Critical Review. Chemosphere 2018, 204, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Tang, J.; Xia, S. Effective Removal of Inorganic Mercury and Methylmercury from Aqueous Solution Using Novel Thiol-Functionalized Graphene Oxide/Fe-Mn Composite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeddine, Z.; Batonneau-Gener, I.; Ghssein, G.; Pouilloux, Y. Recent Advances in Heavy Metal Adsorption via Organically Modified Mesoporous Silica: A Review. Water Switz. 2025, 17, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, B.S.; Wang, J.S.; Lu, J.F.; Siao, F.Y.; Chen, B.H. Adsorption of Toxic Mercury(II) by an Extracellular Biopolymer Poly(γ-Glutamic Acid). Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussout, H.; Ahlafi, H.; Aazza, M.; Maghat, H. Critical of Linear and Nonlinear Equations of Pseudo-First Order and Pseudo-Second Order Kinetic Models. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2018, 4, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xia, S.; Lyu, J.; Tang, J. Highly Efficient Removal of Aqueous Hg2+ and CH3 Hg+ by Selective Modification of Biochar with 3-Mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1646–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Meng, D.; Ma, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, W.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, L.; Li, B.; Huang, W. Carboxyl-Functionalized TiO2 as a Highly Efficient Adsorbent for Separation, Enrichment, and Immobilization of Cu(II), Pb(II), and Hg(II). Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, E.; Lampou, A.; Kellartzis, I.; Karfaridis, D.; Zouboulis, A. Thiol-Functionalization Carbonaceous Adsorbents for the Removal of Methyl-Mercury from Water in the Ppb Levels. Water Switz. 2022, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarnejad, R.; Afshar, S.; Pirhadi, M.; Mirhosseini, M. Mercury (II) Adsorption Process from an Aqueous Solution through Activated Carbon Blended with Fresh Pistachio Green Shell Powder. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, Ş.; Şahan, T.; Karabakan, A. Response Surface Approach for Optimization of Hg(II) Adsorption by 3-Mercaptopropyl Trimethoxysilane-Modified Kaolin Minerals from Aqueous Solution. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 2225–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.D.S.D.; Bao, S.X.; Musah, B.I. Metakaolin-Based Geopolymer for Mercury Removal from Model Wastewater. Water Environ. Res. 2022, 94, e10779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, S.; Guerrero, B.; Benítez, Á.; Ramos, D.R.; Santaballa, J.A.; Canle, M.; Rosado, D.; Moreno-Andrés, J. Inactivation of E. Coli and S. Aureus by Novel Binary Clay/Semiconductor Photocatalytic Macrocomposites under UVA and Sunlight Irradiation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Oves, M.; Khan, M.S.; Habib, S.S.; Memic, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 6003–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetta, S.; Bonetta, S.; Motta, F.; Strini, A.; Carraro, E. Photocatalytic Bacterial Inactivation by TiO2-Coated Surfaces. AMB Express 2013, 3, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Sun, H.; Shang, Y.; Zeng, S.; Qin, Z.; Yin, S.; Li, J.; Liang, S.; Lu, G.; Liu, Z. Spiky Nanohybrids of Titanium Dioxide/Gold Nanoparticles for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation and Anti-Bacterial Property. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 535, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaysri, R.; Tubchareon, T.; Praserthdam, P. One-Step Synthesis of Amine-Functionalized TiO2 Surface for Photocatalytic Decolorization under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 45, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Content (wt%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | Na2O | K2O | CaO | SiO2/Al2O3 | |

| RK | 49.56 | 37.58 | 0.10 | 0.70 | - | 1.90 | 0.12 | 1.32 |

| ABK | 56.06 | 27.78 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 3.44 | 1.82 | 0.08 | 2.02 |

| ABK–TiO2 | 47.78 | 23.05 | 0.86 | 23.92 | 1.51 | 1.75 | 0.06 | 2.07 |

| ABK–TiO2–APTES | 49.81 | 22.43 | 0.74 | 22.88 | 1.60 | 1.55 | - | 2.22 |

| RK | ABK | ABK–TiO2 | ABK–TiO2–APTES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area (m2/g) | 17 | 94 | 95 | 68 |

| Pore volume (cm3/g) | 0.063 | 0.238 | 0.243 | 0.203 |

| Model | Parameter | ABK | ABK–TiO2 | ABK–TiO2–APTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first order | K1 | 0.031 | 0.079 | 0.054 |

| qm | 6.2 | 15.1 | 22.2 | |

| R2 | 0.981 | 0.987 | 0.985 | |

| SSE | 0.762 | 2.803 | 7.768 | |

| Pseudo-second order | K2 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| qm | 8.1 | 17.1 | 26.2 | |

| R2 | 0.978 | 0.999 | 0.996 | |

| SSE | 0.858 | 0.315 | 1.923 | |

| Langmuir | qm | 8.4 | 18.0 | 28.4 |

| R2 | 0.974 | 0.968 | 0.961 | |

| KL | 0.032 | 0.134 | 0.105 | |

| SSE | 0.560 | 5.261 | 15.395 | |

| Freundlich | n | 1.902 | 2.803 | 2.400 |

| R2 | 0.960 | 0.895 | 0.920 | |

| KF | 0.632 | 3.942 | 4.953 | |

| SSE | 0.856 | 17.681 | 32.395 |

| Adsorbent | Size | Initial Concentration (mg/L) | Dosage (g/L) | Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Removal (%) | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Kaolin | <100 µm | 300 | 0.5 | 10.1–10.9 | - | [25] |

| 3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane modified kaolin | ≤125 µm | 30.83 | 0.1 | 30.1 | 98.0 | [64] |

| Polypyrrole-functionalized Fe3O4/kaolin | - | 50 | 0.05 | 317.7 | - | [26] |

| Metakaolin-based geopolymer | 150 µm | 50 | 0.05 | 38.0 | 65.1 | [65] |

| L-cysteine and polypyrrole-functionalized magnetic kaolin | - | 40 | 0.05 | 482.7 | - | [27] |

| TiO2-loaded APTES grafted kaolin | ≤125 µm | 70 | 1.5 | 25.6 | 54.5 | This study |

| Bacteria | RK (mg/mL) | ABK (mg/mL) | ABK–TiO2 (mg/mL) | ABK–TiO2–APTES (mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (BL21) | 10 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| S. aureus | 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdulsalam, A.A.; Khabdullina, S.; Sairan, Z.; Sarbassov, Y.; Pirman, M.; Amrasheva, D.; Kyzas, G.Z.; Pham, T.T.; Arkhangelsky, E.; Poulopoulos, S.G. Mercury Removal and Antibacterial Performance of A TiO2–APTES Kaolin Composite. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040048

Abdulsalam AA, Khabdullina S, Sairan Z, Sarbassov Y, Pirman M, Amrasheva D, Kyzas GZ, Pham TT, Arkhangelsky E, Poulopoulos SG. Mercury Removal and Antibacterial Performance of A TiO2–APTES Kaolin Composite. Sustainable Chemistry. 2025; 6(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulsalam, Awal Adava, Sabina Khabdullina, Zhamilya Sairan, Yersain Sarbassov, Madina Pirman, Dilnaz Amrasheva, George Z. Kyzas, Tri Thanh Pham, Elizabeth Arkhangelsky, and Stavros G. Poulopoulos. 2025. "Mercury Removal and Antibacterial Performance of A TiO2–APTES Kaolin Composite" Sustainable Chemistry 6, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040048

APA StyleAbdulsalam, A. A., Khabdullina, S., Sairan, Z., Sarbassov, Y., Pirman, M., Amrasheva, D., Kyzas, G. Z., Pham, T. T., Arkhangelsky, E., & Poulopoulos, S. G. (2025). Mercury Removal and Antibacterial Performance of A TiO2–APTES Kaolin Composite. Sustainable Chemistry, 6(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040048