Revisiting the Spectral Displacement Method for Estimation of the Binding Constants in Systems Involving Multiple Equilibria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Hazard Statements

2.2. Spectrophotometric Measurements

2.3. Concepts and Mathematical Background

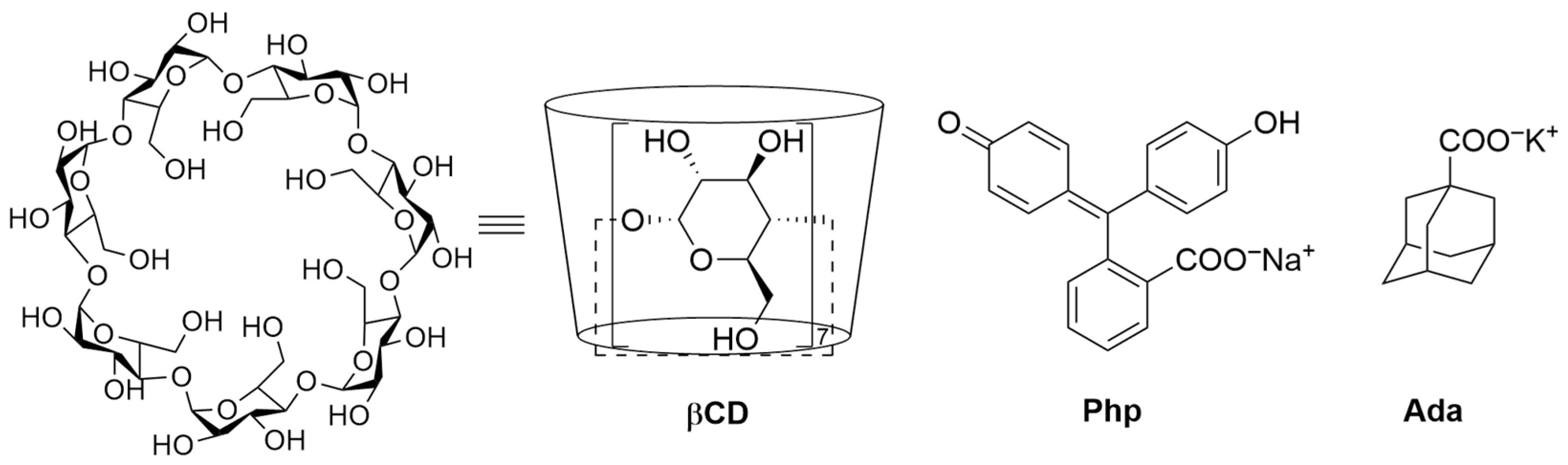

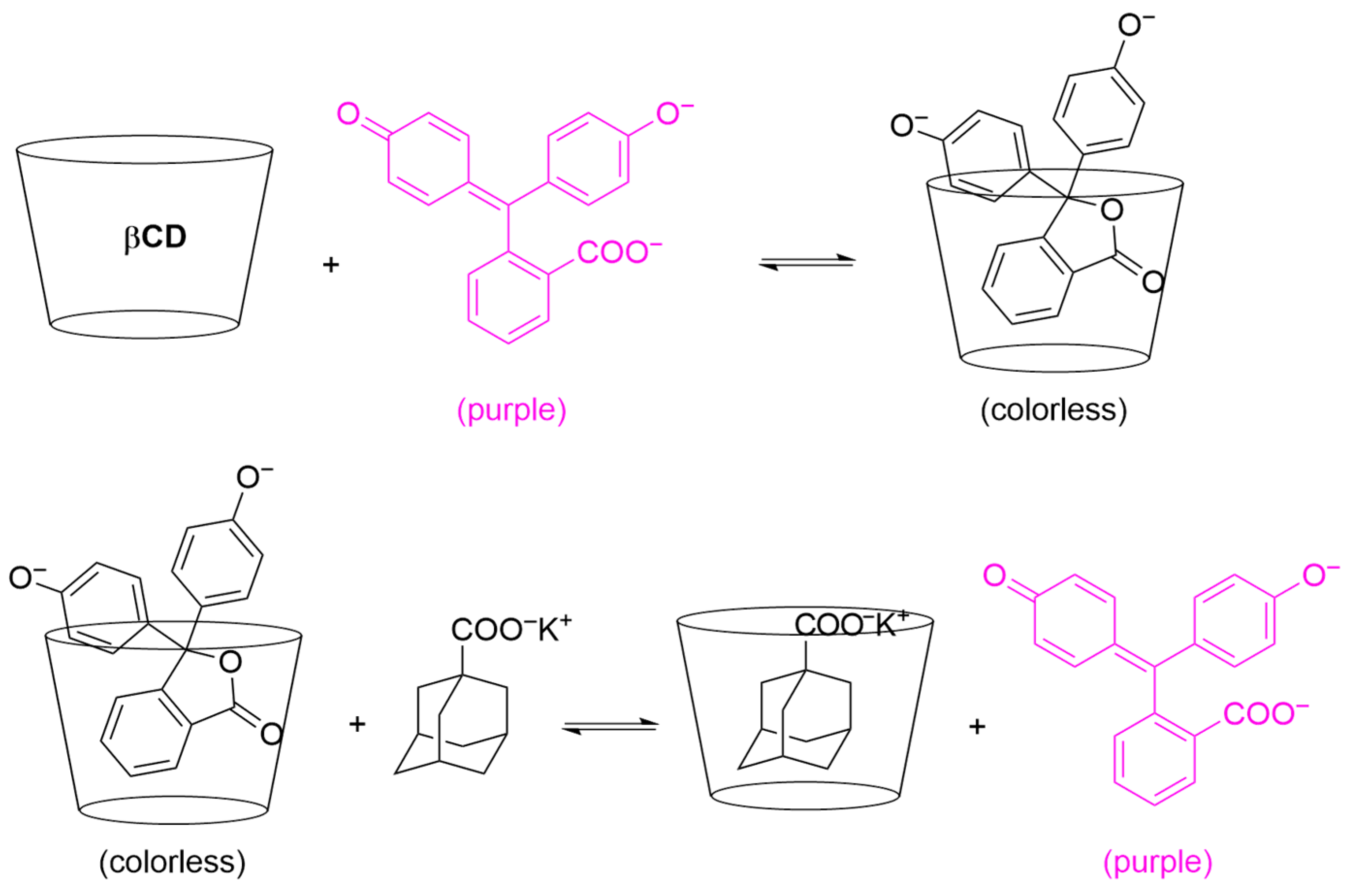

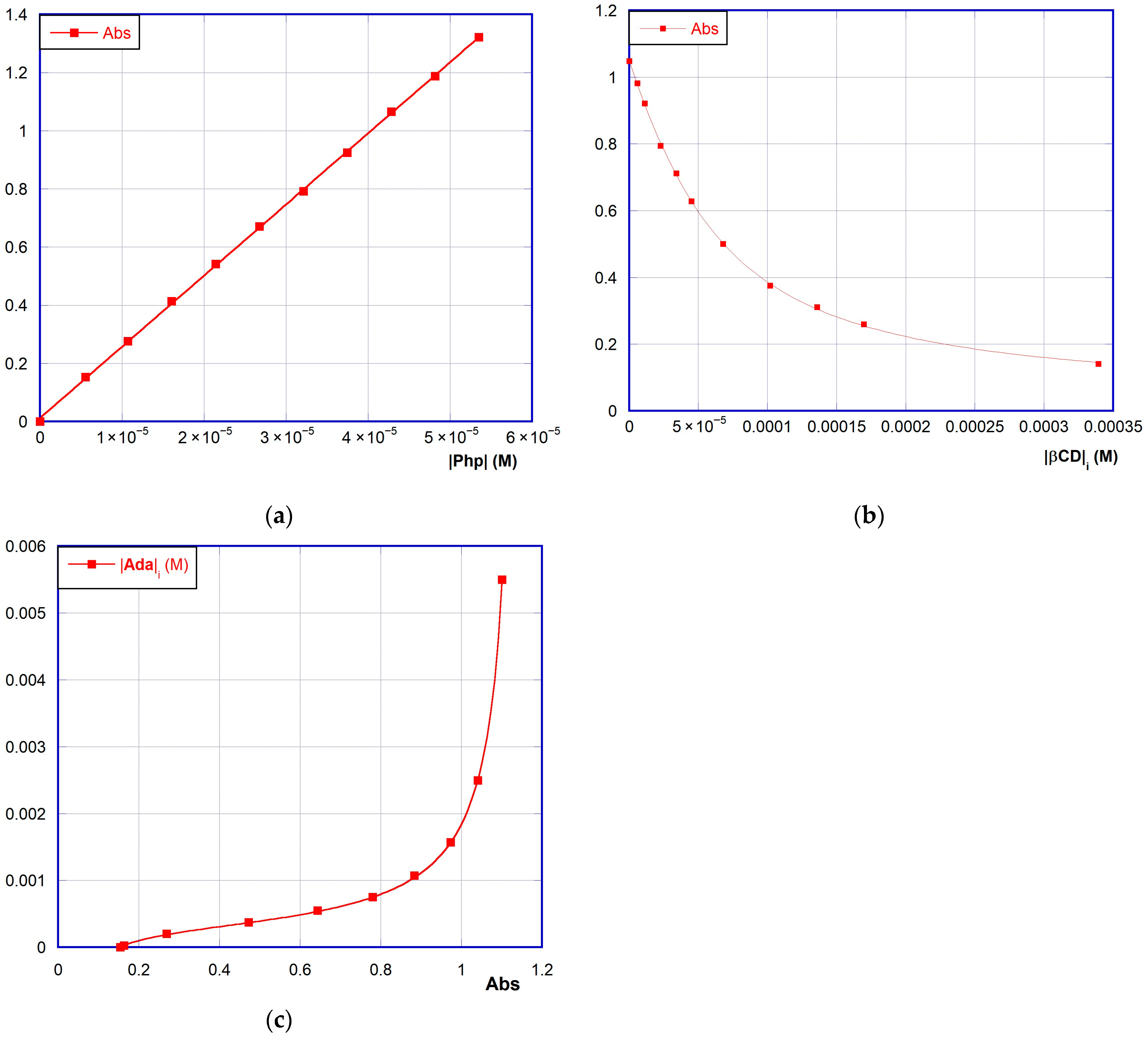

2.3.1. Formation of a Single 1:1 Host–Guest Inclusion Complex

2.3.2. Multiple Equilibria: The Spectral Displacement Method

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Php | Phenolphthalein |

| βCD | β-cyclodextrin |

| Ada | Adamantane |

| KPhp | Binding constant of βCD-Php complex |

| KAda | Binding constant of βCD-Ada complex |

References

- Williams, G.T.; Haynes, C.J.E.; Fares, M.; Caltagirone, C.; Hiscock, J.R.; Gale, P.A. Advances in Applied Supramolecular Technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2737–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintzheimer, S.; Reichstein, J.; Groppe, P.; Wolf, A.; Fett, B.; Zhou, H.; Pujales-Paradela, R.; Miller, F.; Müssig, S.; Wenderoth, S.; et al. Supraparticles for Sustainability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2011089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Meng, Y.; Wang, X. Sustainable Supramolecular Polymers. Chempluschem 2024, 89, e202300694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Lin, W.; Huang, F.; Sessler, J.; Khashab, N.M. Industrial Separation Challenges: How Does Supramolecular Chemistry Help? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 19143–19163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivo, G.; Capocasa, G.; Del Giudice, D.; Lanzalunga, O.; Di Stefano, S. New Horizons for Catalysis Disclosed by Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7681–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonia, E.; Di Vincenzo, A.; Pettignano, A.; Scaffaro, R.; Gulino, E.F.; Conte, P.; Lo Meo, P. Composite RGO/Ag/Nanosponge Materials for the Photodegradation of Emerging Pollutants from Wastewaters. Materials 2024, 17, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Armetta, F.; Riela, S.; Chillura Martino, D.; Lo Meo, P.; Noto, R. Silver Nanoparticles Stabilized by a Polyaminocyclodextrin as Catalysts for the Reduction of Nitroaromatic Compounds. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 408, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janicka, P.; Kaykhaii, M.; Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Gębicki, J. Supramolecular Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Applications. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5035–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savyasachi, A.J.; Kotova, O.; Shanmugaraju, S.; Bradberry, S.J.; Ó’Máille, G.M.; Gunnlaugsson, T. Supramolecular Chemistry: A Toolkit for Soft Functional Materials and Organic Particles. Chem 2017, 3, 764–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, V. Supramolecular Chemistry in Designing Smart Materials. Multidiscip. Res. Arts Sci. Commer. 2024, 13, 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stupp, S.I.; Palmer, L.C. New Frontiers in Supramolecular Design of Materials. MRS Bull. 2024, 49, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M.; Imran, S.; Ahmad Khan, M.; Ahmad, Z.; Ihsan, A.; Qadir, S.; Saba, A. Supramolecular Hydrogels: A Versatile and Sustainable Platform for Emerging Energy Materials. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 401, 124629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumele, O.; Chen, J.; Passarelli, J.V.; Stupp, S.I. Supramolecular Energy Materials. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuri, D.; D’Agostino, S.; Ravarino, P.; Faccio, D.; Falini, G.; Tomasini, C. Water Remediation from Pollutant Agents by the Use of an Environmentally Friendly Supramolecular Hydrogel. ChemNanoMat 2022, 8, e202200093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Ding, X.; Hou, Y.; Ali, W.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Meng, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y. Adsorption and Separation Technologies Based on Supramolecular Macrocycles for Water Treatment. Eco-Environ. Health 2024, 3, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, P.; Chillura Martino, D.F.; Lo Meo, P. The Meaning of Pollution and the Powerfulness of NMR Techniques. In The Environment in a Magnet: Applications of NMR Techniques to Environmental Problems; Conte, P., Chillura Martino, D.F., Lo Meo, P., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2024; Volume 32, ISBN 978-1-83916-734-8. [Google Scholar]

- Szejtli, J. Introduction and General Overview of Cyclodextrin Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connors, K.A. The Stability of Cyclodextrin Complexes in Solution. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1325–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekharsky, M.V.; Inoue, Y. Complexation Thermodynamics of Cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1875–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Yu, G. Preparation and Characterization of a Flavor Compound Inclusion Complex in a Simple Experiment. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 1714–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendicuti, F.; González-Álvarez, M.J. Supramolecular Chemistry: Induced Circular Dichroism to Study Host-Guest Geometry. J. Chem. Educ. 2010, 87, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, P. Analytical Techniques for Characterization of Cyclodextrin Complexes in Aqueous Solution: A Review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 101, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, L.; Kashani, S.; Karimi, J. Molecular Recognition: Detection of Colorless Compounds Based on Color Change. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Meo, P.; D’Anna, F.; Riela, S.; Gruttadauria, M.; Noto, R. Polarimetry as a Useful Tool for the Determination of Binding Constants between Cyclodextrins and Organic Guest Molecules. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 9099–9102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Russo, M.; LoMeo, P. Binding Abilities of a Chiral Calix [4] Resorcinarene: A Polarimetric Investigation on a Complex Case of Study. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2698–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutaj, Z.; Kasprzyk, A.; Czapkiewicz, J. The Spectral Displacement Technique for Determining the Binding Constants of β-Cyclodextrin-Alkyltrimethylammonium Inclusion Complexes. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2003, 47, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.H.; Wilson, L.D.; Headley, J.V.; Peru, K.M. A Spectral Displacement Study of Cyclodextrin/Naphthenic Acids Inclusion Complexes. Can. J. Chem. 2009, 87, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesi, H.A.; Hildebrand, J.H. A Spectrophotometric Investigation of the Interaction of Iodine with Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1949, 71, 2703–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrove, A.E.; Zhong, Z.; Sessler, J.L.; Anslyn, E.V. Algorithms for the Determination of Binding Constants and Enantiomeric Excess in Complex Host : Guest Equilibria Using Optical Measurements. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth, A. Connors Binding Constants: The Measurement of Molecular Complex Stability; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, J.E.; Maclean, S.A.; Reinsborough, V.C. Limitations of the Phenolphthalein Competition Method for Estimating Cyclodextrin Binding Constants. Aust. J. Chem. 1995, 48, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buvári, Á.; Barcza, L.; Kajtár, M. Complex Formation of Phenolphthalein and Some Related Compounds with β-Cyclodextrin. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1988, 1687–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvidge, L.A.; Eftink’, M.R. Spectral Displacement Techniques for Studying the Binding of Spectroscopically Transparent Ligands to Cyclodextrins. Anal. Biochem. 1986, 154, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, R.; Zhang, B. Cholesterol Recognition and Binding by Cyclodextrin Dimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 8495–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijlink, H.W.; Eissens, A.C.; Hefting, N.R.; Poelstra, K.; Lerk, C.F.; Meijer, D.K.F. The Effect of Parenterally Administered Cyclodextrins on Cholesterol Levels in the Rat. Pharm. Res. 1991, 8, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganjali Koli, M.; Fogolari, F. Exploring the Role of Cyclodextrins as a Cholesterol Scavenger: A Molecular Dynamics Investigation of Conformational Changes and Thermodynamics. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Tong, L.; Xu, K.; Zhuo, L.; Tang, B. A Novel Assembly of Au NPs-β-CDs-FL for the Fluorescent Probing of Cholesterol and Its Application in Blood Serum. Analyst 2008, 133, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, A.; Jana, N.R. Fluorescent Detection of Cholesterol Using β-Cyclodextrin Functionalized Graphene. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7316–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russo, M.; Di Vincenzo, A.; Floriano, M.A.; Lo Meo, P. Revisiting the Spectral Displacement Method for Estimation of the Binding Constants in Systems Involving Multiple Equilibria. Sustain. Chem. 2025, 6, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040049

Russo M, Di Vincenzo A, Floriano MA, Lo Meo P. Revisiting the Spectral Displacement Method for Estimation of the Binding Constants in Systems Involving Multiple Equilibria. Sustainable Chemistry. 2025; 6(4):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040049

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusso, Marco, Antonella Di Vincenzo, Michele Antonio Floriano, and Paolo Lo Meo. 2025. "Revisiting the Spectral Displacement Method for Estimation of the Binding Constants in Systems Involving Multiple Equilibria" Sustainable Chemistry 6, no. 4: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040049

APA StyleRusso, M., Di Vincenzo, A., Floriano, M. A., & Lo Meo, P. (2025). Revisiting the Spectral Displacement Method for Estimation of the Binding Constants in Systems Involving Multiple Equilibria. Sustainable Chemistry, 6(4), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem6040049