1. Introduction

The increasing global demand for food, water, and energy, coupled with land degradation and the impacts of climate change, has intensified the search for integrated approaches that maximize resource efficiency while minimizing environmental trade-offs [

1,

2,

3]. Over the past four decades, agrivoltaic (AV) systems combining agricultural production with photovoltaic (PV) electricity generation on the same land have emerged as a promising solution to this challenge. First conceptualized by Goetzberger and Zastrow in 1982 [

4], agrivoltaics were proposed as a response to the growing tension between energy production and agriculture, anticipating future land-use competition. Since then, the concept has evolved from theoretical models to large-scale pilot projects and commercial facilities, with more than a thousand systems currently operating worldwide [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Evidence from Europe, Asia, and Africa consistently demonstrates that agrivoltaics can simultaneously provide food and energy security while optimizing land productivity [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Reference [

13] reported that land productivity can increase by up to 73% when crops are cultivated under PV modules, a finding that spurred the expansion of field trials in France, Italy, and Germany, and was conceptually reinforced by Dupraz [

5] through the land-use efficiency framework. In arid and semi-arid regions, AV systems have been shown to mitigate soil moisture loss, lower soil surface temperatures, and reduce evapotranspiration by 20–60%, thereby improving water-use efficiency [

10,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These benefits are particularly significant under conditions of water scarcity and climate variability, where shading from PV structures creates favorable microclimates for crops [

10,

14]. Technological advances have played a crucial role in expanding the feasibility of AV systems. The introduction of bifacial modules, vertical PV arrays, and single-axis trackers has enabled greater adaptability to diverse agricultural contexts [

18,

19,

20]. For example, [

5] documented significant improvements in both crop yields and energy efficiency under dual-use configurations in temperate regions. Likewise, [

17,

21] showed that in arid regions of the United States, shading from PV panels reduced plant stress, maintained soil humidity, and increased photosynthetic activity compared to control plots without panels. These results underscore the role of AV systems as buffers against extreme climatic conditions [

2,

15].

Beyond biophysical impacts, agrivoltaics also contribute to economic viability, social acceptance, and climate resilience. Studies in Asia and Europe confirm that integrating PV into agricultural landscapes can improve farm incomes by diversifying revenue streams, lowering irrigation costs, and ensuring a stable electricity supply for on-site consumption or grid injection [

6,

22,

23,

24]. For example, [

25] assessed AV tomato production in Spain and found competitive yields with reduced water consumption, underscoring the potential of AV for horticultural applications in water-limited environments. Likewise, studies in East Africa and South Africa demonstrate that AV can simultaneously support rural electrification and food security, reinforcing its potential as a tool for sustainable development in regions with significant infrastructure gaps [

9,

26,

27]. At the same time, AV systems contribute to climate mitigation and adaptation by promoting renewable energy generation, thereby supporting decarbonization goals aligned with the Paris Agreement and the EU Green Deal [

8,

28,

29]. Furthermore, microclimatic regulation under PV structures reduces crop vulnerability to heat stress and drought, positioning AV as a technology that enhances resilience to climate extremes [

10,

13,

14]. From a land management perspective, agrivoltaics foster synergies between energy and food sectors, reducing competition for land resources, an essential advantage in densely populated or resource-constrained countries [

5,

22,

30]. Recent systematic reviews and bibliometric analyses confirm the rapid growth of AV research, particularly since 2015 [

6,

7,

31]. These studies identify three main research clusters: (i) optimization of technical configurations (e.g., panel height, spacing, inclination, and transmissive materials) [

18,

32,

33], (ii) evaluation of agronomic performance across diverse crops [

10,

25], and (iii) assessment of socio-economic and policy frameworks supporting AV adoption [

8,

24]. However, while evidence from Europe, North America, and Asia is robust, studies in Latin America and Africa remain comparatively limited, despite their abundant solar resources and growing agricultural pressures [

9,

34].

The international trajectory of agrivoltaics demonstrates consistent technical, agronomic, and socio-economic benefits that position AV systems as leading candidates for sustainable land-use innovation [

6,

7,

35]. They have been shown to reduce evapotranspiration, enhance water-use efficiency, stabilize microclimates, and simultaneously produce clean energy and food [

10,

13,

15,

17]. Technological improvements continue to expand system adaptability [

18,

19,

20], while economic assessments confirm profitability across diverse contexts [

22,

23,

24]. This global evidence forms the baseline from which this study departs. However, despite these advances, there remains a gap in applying agrivoltaics to complex socio-political environments, such as post-conflict territories, and in frameworks that expand beyond the traditional WEF nexus to include soil, climate, and communities [

8,

36,

37,

38,

39].

As example, in Latin America, the application of AV systems remains limited and fragmented. While pioneering projects have been implemented in Mexico, Brazil, and Chile, most are small-scale experimental plots or feasibility studies, with few systematic assessments of technical, economic, or social outcomes [

6,

19,

34,

35]. In Mexico, experiments have explored shade-tolerant crops under PV arrays [

6,

35]; in Brazil, research has examined integration with agroecological practices and community-based energy cooperatives [

19,

40]; and in Chile, studies have highlighted synergies with viticulture, demonstrating potential water savings and resilience to extreme droughts [

17,

34,

41]. In Colombia, the evidence is even scarcer. Institutions such as the Unidad de Planificación Rural Agropecuaria (UPRA), the Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales (IDEAM), and the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE) have identified the urgent need for sustainable land management and rural electrification, particularly in post-conflict regions [

42,

43,

44,

45]. However, most available documents remain limited to policy guidelines, technical potential assessments, or energy transition strategies [

34,

38,

39,

46], and unlike Europe or the United States, Colombia lacks demonstration sites or field-scale evaluations [

34,

38,

39]. This absence is particularly critical in PDET and ZOMAC municipalities, prioritized in the 2016 Peace Agreement as territories requiring targeted investments for sustainable development [

38,

39]. These regions face overlapping challenges: limited connectivity to the national grid, high dependence on rainfed agriculture, degraded soils, and persistent socio-economic inequalities [

45,

46,

47]. Although rural development policies emphasize renewable energy deployment and agricultural modernization, they have not yet considered agrivoltaics as a strategic tool to address these challenges simultaneously [

43,

44]. The lack of integration between energy transition and agricultural development agendas reinforces this gap, leaving post-conflict territories at risk of being excluded from innovative sustainability solutions [

38,

39,

43,

44,

46].

A further research gap concerns the conceptual frameworks applied to agrivoltaics. Most international studies adopt the classical WEF nexus, focusing on resource efficiencies among water, energy, and food [

1,

3,

30,

48]. While this approach has proven useful, it remains insufficient to capture the complexity of fragile rural contexts such as those in Colombia. In these settings, soil degradation, climate variability, and community resilience are equally critical dimensions that determine the success of interventions [

8,

27,

37,

47,

49,

50]. Their omission from most AV research limits the capacity to fully assess long-term sustainability and socio-political feasibility. For instance, while water use efficiency and energy generation are central indicators, they fail to capture issues such as soil conservation, vulnerability to climate extremes, or the role of communities in governance and adoption [

8,

37]. Consequently, a clear twofold gap persists: first, the absence of empirical studies on agrivoltaics in Colombia and Latin America, particularly in post-conflict regions [

19,

34,

38,

39,

41]; and second, the lack of analytical frameworks that integrate soil, climate, and communities alongside water, energy, and food [

8,

37,

47]. This dual gap constrains the ability of policymakers and practitioners to design evidence-based strategies aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Colombian Peace Agreement, and international climate commitments [

3,

28].

Addressing these gaps requires moving beyond fragmented studies and adopting integrative frameworks capable of capturing the multidimensional role of agrivoltaics. Expanding from WEF to WEFSCC is not merely a conceptual innovation but a necessity to reflect the real challenges of Colombian post-conflict territories. By explicitly incorporating soil (land-use optimization and conservation), climate (variability and adaptation), and communities (social recovery and governance), the WEFSCC framework provides a more accurate lens for evaluating agrivoltaics in fragile contexts [

27,

47,

49,

50]. This perspective aligns with recent calls in the nexus literature to move from narrow technical assessments toward more holistic and policy-relevant analyses [

1,

2,

3]. While agrivoltaics have demonstrated significant benefits internationally, few studies connect these systems to post-conflict sustainable development strategies, particularly in Colombia [

34,

38,

39,

46]. To address this gap, the present study integrates agronomic, hydrological, energy, financial, and socio-political dimensions within a WEFSCC framework [

8,

37,

47,

49], directly responding to the limitations identified in previous research [

1,

6,

7]. Specifically, the research develops an integrative assessment of agrivoltaic systems as tools for sustainable land management in Colombia’s post-conflict regions, focusing on two municipalities—Pisba (Boyacá) and Cabrera (Cundinamarca)—both classified as PDET/ZOMAC territories [

43,

44,

45,

46]. These areas represent national priorities for sustainable development but remain constrained by infrastructure deficits, land-use conflicts, and high vulnerability to climate variability.

The main contribution of this work lies in bridging the technical, economic, and socio-environmental dimensions of agrivoltaics within a single analytical structure that combines quantitative modeling with contextual interpretation [

6,

7,

8]. Specifically, the research integrates: (i) agroclimatic and spatial analysis, using GIS v3.32 tools and IDEAM datasets were obtained using the official web platform Consulta y Descarga de Datos Hidrometeorológicos—DHIME to characterize solar irradiance, slope, and land-use conditions [

45,

51,

52]; (ii) crop yield and water balance modeling, contrasting traditional surface irrigation with hydroponic systems to estimate reductions in evapotranspiration and water demand [

36,

53,

54]; (iii) photovoltaic energy simulation, evaluating the generation potential of 30 kW systems under site-specific conditions [

19,

20,

33]; (iv) economic evaluation, incorporating Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), Free Cash Flow (FCL), and Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) under different scenarios [

22,

23,

24]; and (v) socio-environmental interpretation, examining how agrivoltaics contribute to community resilience, land restoration, and climate adaptation within post-conflict reconstruction programs [

27,

38,

39,

47,

50]. By integrating these components, the study addresses the fragmentation that characterizes most previous research, which often isolates either the technical or the socio-economic aspects of AV systems [

1,

6,

7]. This multidimensional approach not only quantifies potential gains in water, energy, and agricultural productivity but also identifies synergies and trade-offs across the six dimensions of the WEFSCC nexus [

5,

22,

28]. For example, while hydroponic AV systems improve water efficiency and crop yields, they also require higher initial investments and technical capacity, which may influence community adoption and equity outcomes [

24,

25,

27,

55].

Another major contribution of this study is the contextualization of agrivoltaics within Colombia’s peacebuilding agenda. Post-conflict regions in Colombia represent unique socio-ecological systems where land-use planning intersects with social reconciliation and climate adaptation [

27,

43,

44,

47]. By situating agrivoltaic deployment in PDET and ZOMAC municipalities, the study demonstrates how renewable energy solutions can directly contribute to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2 (Zero Hunger), 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), 13 (Climate Action), and 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) [

3,

8,

28]. This alignment also provides a replicable model for other Global South countries facing similar challenges of rural inequality, post-conflict reconstruction, and ecological vulnerability [

50,

56,

57]. Furthermore, the study contributes methodologically by offering a scalable decision-support framework. The integration of spatial, hydrological, and financial modeling allows replication in other regions [

22,

23,

36], while the inclusion of the WEFSCC perspective ensures that results can inform both engineering design and policy formulation [

8,

37,

47]. This approach aligns with the current shift in nexus research toward actionable, transdisciplinary applications that connect scientific evidence with governance and planning processes [

1,

2,

3]. In addition, this paper contributes to the broader scientific debate by operationalizing the WEFSCC nexus through empirical data and scenario analysis [

8,

37]. While the WEF nexus has provided a valuable foundation [

1,

3,

48], its expansion to include soil, climate, and communities allows a more comprehensive understanding of system interdependencies. This conceptual advance responds directly to recent calls for a “WEF-plus” paradigm capable of incorporating equity, resilience, and environmental feedback into decision-making [

2,

27,

50]. By doing so, this study not only provides a country-specific assessment for Colombia but also enriches global discussions on the role of agrivoltaics in sustainable land-use transitions. Importantly, this research advances the understanding of agrivoltaics as catalysts of territorial resilience. In Colombia, where historical conflicts have disrupted rural livelihoods and degraded natural resources, agrivoltaic systems can become platforms for social innovation—combining local participation, technology transfer, and environmental restoration. The findings suggest that agrivoltaics not only improve resource efficiency but also reframe how land is valued and used, transforming spaces of conflict into spaces of cooperation.

These interdependencies generate both synergies and trade-offs that must be explicitly modeled to inform sustainable planning [

2,

8,

58]. From a policy perspective, adopting a WEFSCC approach enables governments to design interventions that transcend sectoral boundaries. In Colombia, applying this framework can help bridge the gap between the energy transition agenda and rural development policies, ensuring that renewable energy deployment simultaneously supports agricultural productivity, soil conservation, and peacebuilding [

38,

39,

43,

44,

46]. The WEFSCC nexus thus provides a foundation for cross-sectoral coordination, facilitating the development of incentives and governance instruments that reflect the integrated nature of resource systems.

In summary, this conceptual advancement ensures that agrivoltaic systems are evaluated not only in terms of efficiency metrics but also in relation to ecological integrity, climate resilience, and social justice principles that underpin the sustainable reconstruction of rural Colombia. In light of these conceptual and empirical gaps, this study evaluates how agrivoltaic (AV) systems can function as integrative instruments for sustainable land management in Colombia’s post-conflict territories, framed within the Water–Energy–Food–Soil–Climate–Communities (WEFSCC) nexus. Addressing sustainability challenges in fragile regions requires not only technological innovation but also a systemic understanding of the socio-ecological interdependencies that shape these landscapes. Accordingly, the research adopts a transdisciplinary approach that links engineering analysis with environmental, economic, and social dimensions, aiming to generate actionable insights for both policy and practice. The overall objective of this work is to assess the technical, economic, environmental, and social feasibility of agrivoltaic systems in selected post-conflict municipalities of Colombia through an integrative WEFSCC framework that captures resource interdependencies and identifies pathways toward sustainable land management and community resilience. To achieve this, the study first characterizes the agroclimatic, hydrological, and spatial conditions of the municipalities of Pisba and Cabrera, both part of the PDET and ZOMAC programs, using QGIS-based tools v3.32 and national datasets (IDEAM, UPRA, DANE) to evaluate their suitability for agrivoltaic deployment. It then models crop productivity and water consumption under traditional irrigation and hydroponic systems, quantifying the potential reductions in evapotranspiration and water demand under agrivoltaic shading. Photovoltaic energy generation for 30 kW systems is simulated at both sites to estimate hourly, daily, and monthly energy outputs under varying tilt and solar incidence conditions. Economic performance is analyzed through Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Free Cash Flow (FCL) indicators, under conservative, moderate, and optimistic scenarios. Finally, all results are integrated within the WEFSCC framework to identify synergies and trade-offs among the six resource dimensions (water, energy, food, soil, climate, and communities) and to derive implications for local governance, policy design, and sustainable territorial planning. Building on these objectives, the study is guided by the following research questions: (i) How can agrivoltaic systems contribute to reducing water demand and improving crop productivity in rural post-conflict territories? (ii) What is the expected energy generation potential and economic viability of small-scale agrivoltaic installations (30 kW) under Colombian agroclimatic conditions? (iii) How do soil, climate, and community dynamics modify the traditional interactions of the WEF nexus in fragile territories? (iv) What policy instruments and governance mechanisms could support the adoption of agrivoltaic systems as a strategy for land restoration, climate adaptation, and peacebuilding? By articulating these objectives and research questions, this study aims to provide a comprehensive and replicable framework for assessing agrivoltaics within complex socio-environmental contexts. The proposed approach not only quantifies the technical and financial viability of dual-use systems but also situates them within a broader narrative of sustainability, resilience, and post-conflict reconstruction. This orientation ensures that the findings are relevant to engineers, planners, policymakers, community organizations, and international cooperation agencies committed to promoting integrated development pathways. The subsequent sections describe in detail the methodological structure, analytical models, and data sources employed to operationalize the WEFSCC nexus and evaluate agrivoltaic potential in Pisba and Cabrera.

2. Conceptual Framework: The WEFSCC Nexus

The conceptual framework guiding this study extends the conventional Water–Energy–Food (WEF) nexus to incorporate three additional and interdependent dimensions—Soil, Climate, and Communities, forming the WEFSCC nexus. This expansion responds to the growing recognition that while the classical WEF model is valuable for resource optimization, it is often insufficient to capture the complex socio-ecological realities of rural territories in the Global South, particularly in post-conflict regions such as those in Colombia. The WEF nexus traditionally emphasizes the quantitative interdependencies among resource flows: water availability affects food production; food systems depend on energy for irrigation and processing; and energy systems, in turn, require water for generation and cooling [

1,

3,

48]. However, this triad often treats land, climate, and social systems as external boundary conditions rather than integral components of resource governance. Recent studies have criticized this limitation, stressing that the exclusion of soil quality, climate feedback, and community dynamics constrains both the explanatory and practical power of nexus models [

27,

49,

50]. In response, broader frameworks—such as WEF-Land, WEF-Ecosystem, or WEF-Climate-Community nexuses—have been proposed to explicitly integrate ecological and social variables, thereby enhancing resilience, equity, and sustainability [

8,

37,

51].

The Soil Dimension represents the foundational substrate linking food, water, and energy systems. In agrivoltaic configurations, soil is not merely a passive medium for crop growth; it also shapes hydrological processes, microclimate regulation, and land stability [

47,

49]. The installation of PV structures alters soil albedo, temperature, and moisture retention, which can either improve or degrade soil health depending on design and management [

9,

14]. Studies in arid zones demonstrate that partial shading reduces soil evaporation, increases microbial activity, and enhances carbon sequestration [

13,

14,

16,

35,

47]. Conversely, poorly designed installations may cause compaction, erosion, or hydrophobicity. For Colombia, where land degradation affects more than 30% of agricultural soils, the soil dimension is central to sustainable land-management strategies [

42,

44,

47]. Integrating soil into the nexus enables evaluation of how agrivoltaic systems contribute to conservation, erosion control, and the restoration of degraded lands, aligning with national goals under the Misión de Suelos and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

The Climate Dimension positions climate as both a driver and a constraint in WEF interactions. Variability in precipitation, temperature, and solar radiation directly shapes agricultural productivity, irrigation demand, and PV performance. In the classical WEF framework, climate is usually treated as an exogenous factor; within WEFSCC, it becomes endogenous a feedback variable that both influences and is influenced by resource management decisions [

1,

2,

3]. Agrivoltaics provide a distinctive pathway for climate adaptation and mitigation: by reducing evapotranspiration and creating cooler microclimates, they help crops withstand heat and drought stress [

13,

15,

17,

58], while simultaneously generating renewable energy that offsets greenhouse gas emissions from fossil sources. In this sense, AV systems operate as climate-smart infrastructures. Their dual capacity to mitigate and adapt makes them especially relevant in Colombia, where ENSO-driven variability causes recurrent droughts and floods that destabilize agricultural output [

42,

45,

51]. Thus, the WEFSCC framework integrates climate not as a background condition but as a co-evolving dimension whose stability depends on sustainable land and energy practices.

The Communities Dimension constitutes the governance backbone of any nexus system. Resource flows are not managed by institutions alone but also by social networks, cooperatives, and local stakeholders, whose participation determines the long-term success of technological interventions [

3,

7,

27]. Within WEFSCC, the community dimension emphasizes agency, equity, and inclusion elements largely absent from technocratic WEF models. In Colombia’s post-conflict territories, communities are rebuilding livelihoods amid historical inequities and institutional fragility [

38,

39,

59]. Agrivoltaic projects in such contexts can foster social cohesion by providing shared energy infrastructure, generating employment, and strengthening food security, while also serving as platforms for education and demonstration [

26,

40,

57]. Moreover, the inclusion of communities enables the nexus to capture feedback loops between governance and resource efficiency: empowered communities manage water and land more sustainably, while trust and participation reduce project failure rates [

8,

50,

60]. In this sense, the WEFSCC framework aligns with a human-centered sustainability paradigm, linking technical outcomes with social well-being.

Taken together, the Soil, Climate, and Communities dimensions complete the WEFSCC lens through which we examine agrivoltaics in post-conflict territories; the next section operationalizes this framework for Pisba and Cabrera, detailing the datasets (IDEAM, UPRA, DANE), spatial and agroclimatic screening, crop–water balance modeling under surface irrigation and hydroponics, 30 kW PV generation simulations, and the economic evaluation (NPV, IRR, FCL, LCOE) and sensitivity analyses, as well as the integration procedure used to map WEFSCC synergies and trade-offs and derive governance-relevant insights.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Site Selection

The study was conducted in two rural municipalities of Colombia, Pisba (Boyacá) and Cabrera (Cundinamarca), both classified as priority territories under the Development Programs with a Territorial Focus (PDET) and the Zones Most Affected by Armed Conflict (ZOMAC) frameworks established after the 2016 Peace Agreement. These municipalities represent contrasting agroecological and socioeconomic conditions typical of Colombia’s Andean region and were selected for their relevance to post-conflict rural development and their suitability for implementing agrivoltaic (AV) systems within the Water–Energy–Food–Soil–Climate–Communities (WEFSCC) nexus [

7,

8,

9,

44,

48,

49].

Pisba is located in the northeastern sector of Boyacá, within the high Andean zone of the Eastern Cordillera, at coordinates 5°43′21″ N, 72°29′07″ W, with altitudes ranging from 1300 to 3400 m.a.s.l., with average temperatures between 13 and 20 °C and annual precipitation exceeding 1200 mm. According to data from the Integrated Agricultural Planning System (SIPRA) of UPRA, Pisba has an agricultural frontier of approximately 12,246 ha, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Cabrera is located in the southern province of Sumapaz, Cundinamarca, at coordinates 3°58′41″ N, 74°29′09″ W, with altitudes between 1800 and 2400 m.a.s.l., with a mean annual temperature of 15–22 °C, annual precipitation exceeding 1000 mm and an agroclimatic setting classified as montane humid forest [

50,

51]. According to data from the Integrated Agricultural Planning System (SIPRA) of UPRA, Cabrera has an agricultural frontier of approximately 14,385 ha, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

For both municipalities, geographic, climatic, and productive data were collected using GIS tools (QGIS 3.28). Data such as solar radiation, precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration were obtained from the IDEAM meteorological stations located in each case study area: Pisba—[35215030] (Boyacá, Pisva), categorized as Climática Ordinaria, at an altitude of 1482 m.a.s.l. (latitude 5.72° N, longitude −72.49° W), with automatic telemetry and active since 15 December 2016; Cabrera—[21190090] (Cundinamarca, Cabrera), categorized as Pluviométrica, at an altitude of 1900 m.a.s.l. (latitude 3.99° N, longitude −74.48° W), with conventional instrumentation and active since 15 September 1958, but also with technical field visits [

45,

52].

Climatic series covered a 10-year (2010–2020) period for maximum and minimum temperature, wind speed, relative humidity, and solar radiation, while a 20-year series (2000–2020) was used for precipitation to ensure robust representation of interannual variability. The reference evapotranspiration (ETo) was calculated using the FAO Penman–Monteith equation, and crop water requirements were derived through the ETo–Kc workflow, applying crop coefficients (Kc) validated for leafy vegetables (lettuce, spinach) and strawberries under partial shade conditions.

The selection of Pisba and Cabrera was based on a multi-criteria evaluation that combined technical, environmental, and social parameters. First, both territories display high solar availability and agricultural vocation, with extensive rural areas lacking connection to the National Interconnected System (SIN). Second, their inclusion in the PDET/ZOMAC programs highlights the need for innovative technologies that promote local employment, sustainable resource management, and energy access. Third, the contrasting agroclimatic conditions of Pisba (humid, high-altitude) and Cabrera (sub-humid, mid-altitude) allow for comparative analysis of AV system performance under different microclimatic and topographic contexts. Finally, both municipalities possess institutional partnerships with local agricultural associations and regional environmental authorities, facilitating the integration of community participation within the WEFSCC framework. Although the analysis focused on Pisba and Cabrera, the selection criteria solar resource availability, altitude range (1800–3400 m.a.s.l.), and agricultural frontier characteristics are also met in other highland municipalities of Cundinamarca such as Tocancipá, Susa, and Nemocón. These areas exhibit analogous agroclimatic and topographic profiles, suggesting strong potential for replicating the agrivoltaic–hydroponic configuration under the same WEFSCC framework.

The characterization of these sites therefore captures the spatial heterogeneity of post-conflict territories and provides a robust foundation for modeling the technical, hydrological, and economic behavior of agrivoltaic systems. The geographic coordinates, long-term actinometric datasets, and agro-environmental attributes defined in this subsection serve as baseline inputs for the subsequent analyses of crop productivity, water consumption, and photovoltaic energy generation.

Potential plots, available electrical infrastructure, and edaphic constraints were identified with the support of UPRA/SIPRA and FAO criteria [

43,

47]. The availability of electrical infrastructure for local-scale energy integration was verified and contextualized within the national energy balance provided by XM [

45].

3.2. Agrovoltaic Conceptual and Analytical Framework Design

The methodology is based on the design and implementation of an agrivoltaic system integrated with vertical hydroponics, referred to in this study as the Productive Unit (PU). This system is conceived to address simultaneously the three core pillars of the nexus: (i) Water, by reducing consumption through the use of hydroponic crops grown in vertical recirculating towers with controlled losses, complemented by rainwater harvesting. (ii) Energy, by generating clean electricity from photovoltaic solar panels to meet the system’s demand while producing surplus energy. (iii) Food, by increasing agricultural productivity per unit of land area through the cultivation of high-efficiency crops with low water requirements.

This integrated approach combines technical modeling, environmental assessment, and socio-economic interpretation, ensuring coherence between physical processes and governance outcomes. The methodological design was structured within the Water–Energy–Food–Soil–Climate–Communities (WEFSCC) nexus to evaluate agrivoltaic (AV) systems as holistic instruments for sustainable land management in post-conflict regions. This framework is supported by previous studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of AV systems in articulating resource flows under conditions of aridity and land-use pressure [

13,

16,

35], as well as their capacity to enhance socio-ecological resilience in rural environments [

58]. The overall methodological workflow from knowledge synthesis and conceptual design to subsystem modeling, integration, and system assessment, is summarized in

Figure 3, which illustrates the sequence from data collection to the integration of results and the evaluation of system adaptability.

The whole process begins with a comprehensive state of the art review, focused on technological, agronomic, and environmental components relevant to AV systems, including hydroponic configurations, solar photovoltaic technologies, and water-saving strategies. In parallel, a design requirements analysis was conducted to determine structural, operational, and environmental constraints under Colombian conditions. The design process of the agrivoltaic system was carried out through an iterative method focused on digital conceptualization and validation, with the objective of optimizing both energy efficiency and structural integration within the agricultural environment. The first step of the project design began with the generation of preliminary concepts that considered the arrangement of solar panels, support modulation, and interaction with the cultivated space. Each concept was modeled using 3D CAD software (Fusion 360 June 2024 release and Inventor 2024 with the FEA module),allowing for the analysis of proportions, assemblies, and potential interferences from the early stages [

57]. This approach facilitated the exploration of multiple configurations prior to moving into more detailed simulations.

Subsequently, structural and performance simulations were conducted to evaluate the resistance of the supports, stability under environmental loads, and stress distribution at critical points, guiding successive adjustments in the geometry and ensuring an adequate safety factor prior to fabricating any physical prototype. This iterative process of modeling and simulation, validated by recent research on AV in different regions [

9], allowed the design to be refined until achieving a digitally validated functional model, represented through renders and animations. In this way, the design ensured a balance between energy efficiency, structural reliability, and implementation feasibility. These inputs informed the formulation of the conceptual model and the selection of simulation tools for water, energy, and crop performance.

The validated conceptual design then informed the technical modeling stage, developed through three parallel subsystems: (i) agricultural and hydroponic performance, represented by crop yield estimation and evapotranspiration modeling; (ii) photovoltaic energy generation, simulated using hourly irradiance and temperature data; and (iii) hydrological balance, evaluating irrigation needs and water recovery under AV shading. Each subsystem was parameterized using climatic, edaphic, and geographic data from IDEAM, UPRA, and NASA-POWER databases. The resulting datasets were harmonized to ensure cross-compatibility and integrated into a common temporal resolution (hourly–monthly).

After subsystem integration, the combined outputs were analyzed under the WEFSCC nexus, incorporating quantitative and qualitative variables. Quantitative indicators included water-use efficiency, energy generation, and economic performance metrics such as Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Free Cash Flow (FCL); when pertinent to investment comparisons, CapEx and OpEx were also considered. Qualitative dimensions such as soil optimization, climate variability, and community participation were examined through semi-structured stakeholder interviews, document analysis, and expert consultation to capture governance factors and contextual constraints that condition adoption and scalability.

A feedback mechanism was incorporated to assess system adaptability. If results indicated that technical or environmental conditions limited scalability, the AV configuration was redesigned considering regional constraints, including soil conservation needs, local climatic variability, and community resource governance. Otherwise, the process advanced toward pilot implementation, performance testing, and long-term monitoring. This iterative structure ensures that the model remains dynamic, context-sensitive, and regionally adaptable.

Overall, this methodological framework enables a comprehensive understanding of agrivoltaic systems beyond their technical efficiency. It captures how water, energy, and food flows interact with soil, climate, and social dimensions, thereby operationalizing the WEFSCC perspective in a quantifiable manner. In addition, the analytical structure provides a foundation for scenario testing, allowing policymakers and practitioners to explore “what-if” conditions related to resource trade-offs and policy interventions and to inform sustainable land-use transitions in post-conflict territories.

Technical Components of the System

The photovoltaic system was designed with Risen Hyper-ion bifacial modules RSM132-8-705BHDG, with a rated capacity of 705 Wp and an efficiency of 22.7%. A total of 43 modules were installed per site, yielding a PV DC nameplate capacity of 30 kWpDC. Modules were mounted at a height of 2.5 m on modular structures oriented due south (azimuth 180°) with a fixed tilt angle of 10–15°, following technical recommendations for agrivoltaics in tropical latitudes but also following technical criteria reported in agrivoltaic projects in Europe and Asia that emphasize the importance of height and orientation for optimizing both energy and agricultural performance [

5,

10,

55]. The installed capacity was the same for Pisba and Cabrera with 43 modules. Stringing configuration consisted of three strings (15S, 14S, 14S) connected to the inverter, ensuring maximum open-circuit voltage and operating voltage remain within equipment limits.

The selected inverter was a Huawei SUN2000-30KTL-M3, with a rated 30 kWAC output and four independent MPPT inputs, providing a DC/AC ratio of 1.0, which lies within recommended design ranges. The installed capacity per municipality was therefore approximately 30 kWpDC/30 kWAC.

The photovoltaic system losses were estimated by considering the main operating factors under real field conditions.

Table 1 shows the breakdown of each loss component and the calculation of the Performance Ratio (PR), using the thermal coefficients of the selected module and conservative assumptions for operation and maintenance.

The support structures, built with guadua (a native bamboo), treated with weather-resistant resins, were designed in accordance with the Colombian Seismic Resistant Code NSR-10, considering wind and seismic loads. This approach aligns with studies that promote the use of sustainable local materials in AV infrastructure [

55].

For the agricultural system, five-level hydroponic towers of the NFT type (Nutrient Film Technique) were employed, with a recirculating nutrient solution, submersible pump of 1.5 hp, and pH and EC controllers. Such configurations have been shown to increase water-use efficiency by up to 60% compared to traditional agriculture [

41,

61]. Each tower level contains 20 planting holes, reaching a cultivation density of approximately 100 plants/m

2. In total, 43 towers were installed in Pisba and Cabrera.

This design integrates clean energy technologies and soilless agriculture, generating a replicable scheme for rural contexts with water and land limitations, in line with international experiences in agrivoltaics combined with hydroponics [

17,

62].

3.3. Crop Selection and Yield Estimation

Crop selection in agrivoltaic–hydroponic systems represent a determining factor for the performance and adaptability of the productive model, since it influences water-use efficiency, light interception, physiological resilience under partial shading, and the economic viability of the integrated unit. In this study, the selection process was conducted using three primary criteria: (i) physiological compatibility with semi-shade conditions; (ii) adaptability to hydroponic systems with short growth cycles and high turnover; and (iii) profitability and local market demand in the selected municipalities.

Based on these parameters, three crops were selected: lettuce (Lactuca sativa), spinach (Spinacia oleracea), and strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). These species are widely documented for their efficient water use, short phenological cycles, and commercial acceptance in Andean and inter-Andean regions. Lettuce and spinach are typical leafy vegetables well suited to hydroponic NFT or vertical recirculation systems, while strawberry represents a reference crop of higher market value but longer cycles. Previous studies report that these crops maintain stable yields under moderate shading (up to 30–40%) without compromising physiological integrity or quality [

63,

64].

3.3.1. Agroclimatic Compatibility and Site Conditions

The agroclimatic characterization for Pisba (1300 to 3400 m.a.s.l.) and Cabrera (1800 and 2400 m.a.s.l.) indicates average annual temperatures of 15–18 °C and mean radiation values between 300 and 500 W m

−2, according to IDEAM historical data. These parameters correspond to the tierra fría and tierra templada zones, suitable for leafy crops with moderate light requirements. The selected species exhibit optimal photosynthetic performance under these ranges, aligning with conditions described in the Manual de Hidroponía [

65] and the Manual de Recomendaciones Técnicas para Cultivo de Fresa en Cundinamarca [

66].

3.3.2. Hydroponic System and Growth Parameters

All crops were modeled under a vertical hydroponic system with recirculation, where nutrient-enriched water flows through stacked towers. Each module integrates an NFT-type circulation loop, minimizing water losses through evapotranspiration and leakage. The nutrient solution maintains a pH between 5.5 and 6.5 and electrical conductivity (EC) between 1.5 and 2.0 mS cm

−1, ensuring macro- and micronutrient balance [

67]. The towers operate with a solution turnover of 3–4 L per plant per cycle [

65].

The general physiological and management parameters used as the basis for simulation are summarized in

Table 2, adapted from Refs. [

65,

67].

3.3.3. Yield Estimation Approach

The theoretical yield estimation for each crop was derived from empirical data reported in national and regional technical manuals. The reference values considered were: 0.1–0.2 kg plant

−1 for lettuce, 0.1–0.25 kg plant

−1 for spinach, and 0.4–0.5 kg plant

−1 for strawberry [

65,

66,

67]. These data served as input for the productivity model used in

Section 4.2. to calculate economic performance indicators (NPV, IRR, and FCL).

To ensure physiological coherence, yield potential was expressed as a function of intercepted radiation, following the general formulation:

where

is the potential yield

,

RUE is the radiation use efficiency specific to each crop, and

represents the absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (50% of total incident solar radiation). For partially shaded agrivoltaic conditions, a transmissivity factor (τ) of 0.72 was applied, following experimental data reported by Weselek et al. [

10]. The RUE values were taken from controlled environment studies: RUE values adopted for modeling were 3.1

for lettuce, 3.8

for spinach, and 2.9

for strawberry, consistent with experimental reports for hydroponic and semi-shaded systems [

63,

64]. This approach ensured comparability among species under controlled light and temperature conditions and provided a reproducible framework to link crop productivity with the agrivoltaic system’s radiation regime.

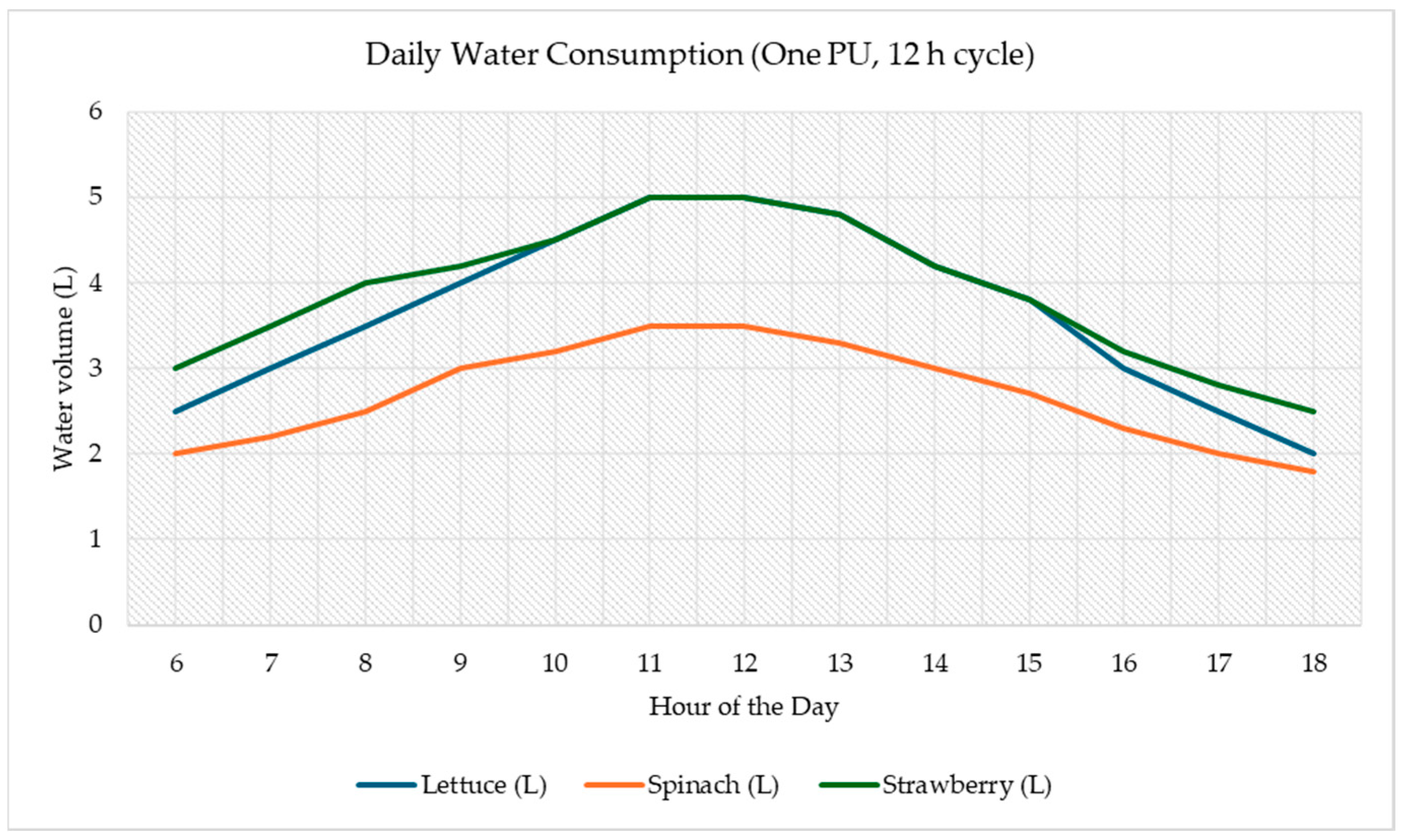

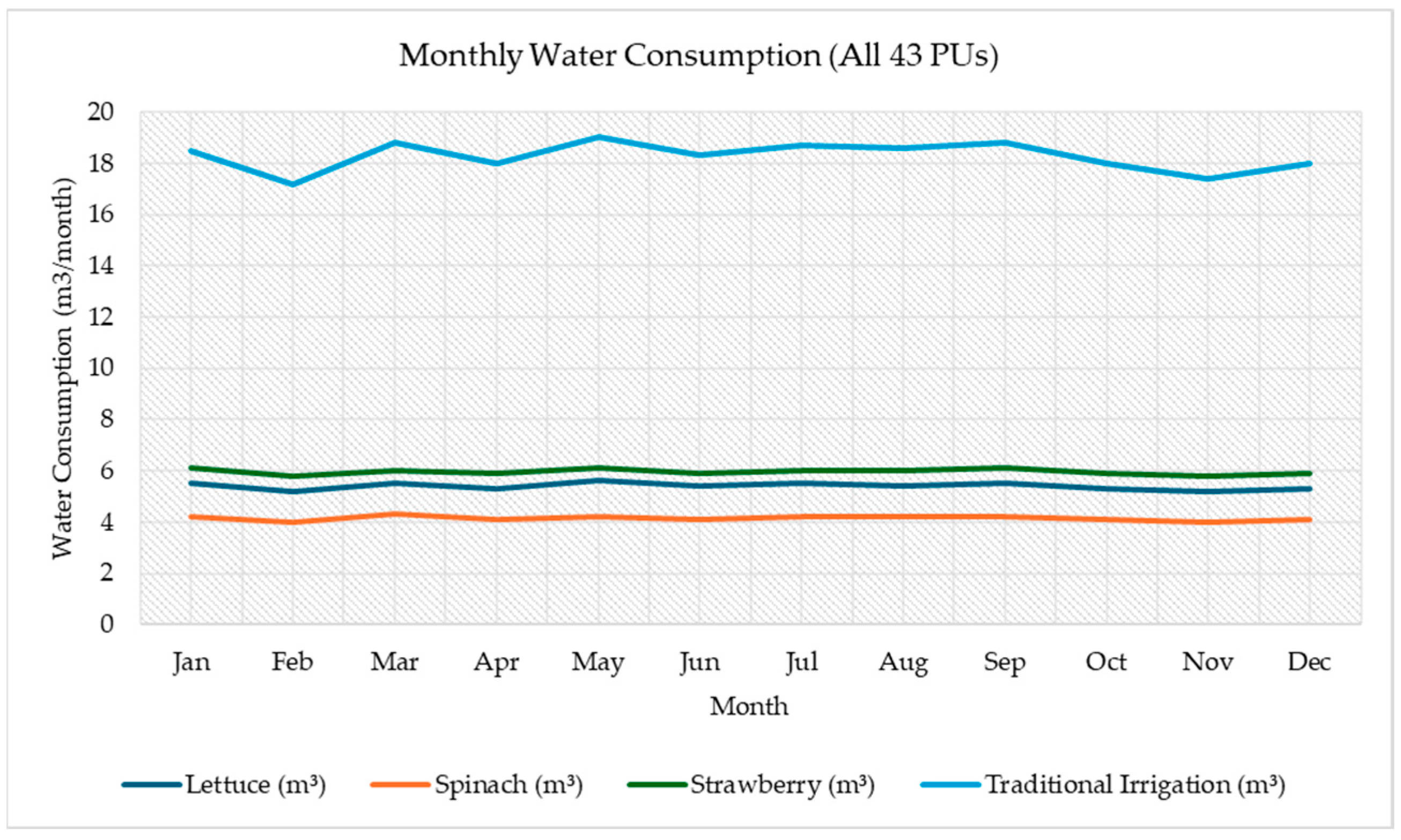

3.4. Water Consumption Assessment

Water consumption analysis aimed to quantify the efficiency of the hydroponic subsystem integrated in the agrivoltaic (AV) configuration, comparing its performance against conventional irrigation practices commonly adopted in Colombian rural systems. The assessment followed a dual approach: (i) estimation of crop water requirements through reference evapotranspiration (ETo) and crop coefficient (Kc) methodology, and (ii) computation of actual water demand under recirculating hydroponic operation, accounting for system losses by evaporation, percolation, and drainage.

Reference evapotranspiration (

ETo) values were derived from IDEAM meteorological stations in Pisba and Cabrera using the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith equation [

36], based on daily temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and global solar radiation. Annual mean

ETo ranged between 2.4 and 4.1 mm day

−1, depending on elevation and vegetation cover. Crop coefficients (

Kc) were assigned for each phenological stage following national hydroponic manuals: lettuce (0.65–1.00), spinach (0.60–0.95), and strawberry (0.70–1.10) [

65,

66,

67]. Total water requirements under open-field conditions were calculated as:

Yielding seasonal consumptions between 420 and 550 mm cycle

−1 for traditional irrigation. These values align with agronomic baselines reported for temperate Andean zones [

68,

69]. The hydroponic subsystem employed a Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) configuration with recirculation and automated loss control, resulting in recapture efficiencies of 60–70% [

70]. Daily nutrient solution volumes were determined from flowmeter readings and adjusted for evapotranspiration using:

where

Er denotes the recovery efficiency. Under standard operation, the NFT modules required 1.2–1.5 L/plant/day, with total cycle consumption of 40–60 m

3/ha, in contrast to 180–220 m

3/ha estimated for open-field irrigation. This represents an overall reduction of 70–80%, consistent with reported AV-hydroponic savings in East Africa [

9] and greenhouse-based WEFE frameworks [

71].

The evaluation of water-use efficiency was conducted through the Water Use Efficiency (

WUE) indicator, defined as the ratio between crop yield and the total volume of water applied during the cultivation cycle, expressed in kilograms per cubic meter (kg m

−3). This metric allows comparison between production systems with different irrigation regimes or technologies. The theoretical expression used follows the formulation:

where

Y is the total crop yield (kg/m), obtained from the productive model described in

Section 3.3 and

W is the cumulative water input (m

3/m) during the cultivation cycle, including irrigation and nutrient-solution replenishment for the hydroponic configuration.

In the case of traditional irrigation, W corresponds to the cumulative evapotranspiration (ETc) derived from the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith method, adjusted by the specific crop coefficient (Kc) and expressed as the water depth applied over the cultivated surface. For the hydroponic agrivoltaic system, W represents the effective volume of nutrient solution delivered and recirculated through the system, corrected by the recovery efficiency to account for evaporative and operational losses.

This formulation enables the quantification of the relative efficiency in water use between both production systems, establishing a dimensionless comparison that can later be correlated with energy consumption and photovoltaic generation in the integrated WEFSCC framework. By maintaining consistency with the FAO [

47] guidelines and national technical manuals [

65,

66,

67], this methodological approach ensures the reproducibility of calculations and provides a standardized basis for developing daily and annual water-consumption curves to be presented in subsequent sections. This formulation enables the quantification of the relative efficiency in water use between both production systems, establishing a dimensionless comparison that can later be correlated with energy consumption and photovoltaic generation in the integrated WEFSCC framework. By maintaining consistency with the Ref. [

47] guidelines and national technical manuals [

65,

66,

67], this methodological approach ensures the reproducibility of calculations and provides a standardized basis for developing daily and annual water-consumption curves to be presented in subsequent sections.

3.5. Energy Generation Estimation

The estimation of photovoltaic (PV) energy generation for the agrivoltaic (AV) system was conducted through a techno-environmental simulation framework that integrates (i) hourly solar resource reconstruction on the plane of array, (ii) PV module thermal-electrical performance, and (iii) system-level derating and availability. Historical time series of global solar radiation, sunshine duration, air temperature, and cloud cover were obtained from IDEAM stations for Pisba and Cabrera to ensure temporal consistency and gap filling. Sunshine duration was used to derive peak sun hours (PSH) and to characterize intra-annual seasonality typical of the Andean bimodal regime, which is necessary to generate daily and monthly production profiles.

3.5.1. Solar Resource Transposition to the Plane of Array (POA)

Hourly global horizontal irradiance (GHI) was decomposed into its beam (DNI) and diffuse (DHI) components using standard clearness-index correlations. The irradiance was then transposed from the horizontal to the tilted plane of the PV array to obtain the plane of array irradiance

as the sum of beam, sky-diffuse, and ground-reflected components:

where

(with

as the incidence angle on the tilted plane),

is estimated with a sky-diffuse anisotropic model, and

with

as the ground albedo and

as the tilt angle. For both sites, tilt and azimuth were set to maximize annual yield under fixed-tilt mounting; row spacing and ground coverage ratio (GCR) were selected to limit inter-row shading and to accommodate the hydroponic towers. The agrivoltaic structural shading was included through an hourly shading factor

derived from the geometric layout (tower height, array elevation, row separation), so that

.

3.5.2. Cell Temperature and Module Power Model

Module cell temperature was computed from ambient conditions using an NOCT/NMOT-based relation:

with NMOT = 43 °C (as specified for the selected module class). The temperature coefficient of maximum power

was applied to adjust power away from STC:

where

is the DC nameplate and

is negative (manufacturer data). DC output was converted to AC using inverter efficiency curves and DC/AC sizing; hourly AC power is then:

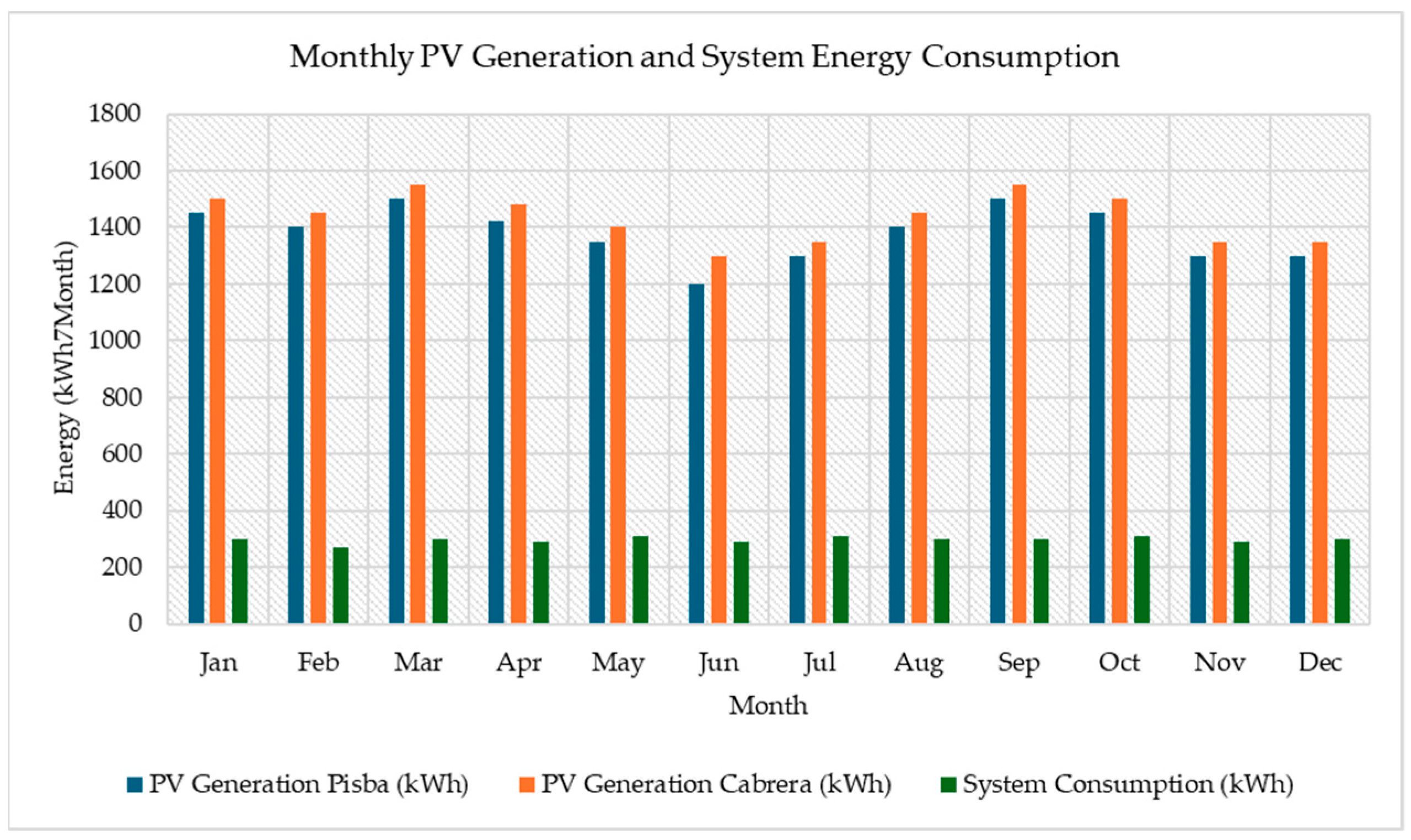

3.5.3. Hourly to Monthly Energy Aggregation and Profiles

Hourly AC energy was computed as

and aggregated to daily and monthly totals:

where

D denotes days in the month, and two families of curves are generated from the same simulation outputs (to be presented in

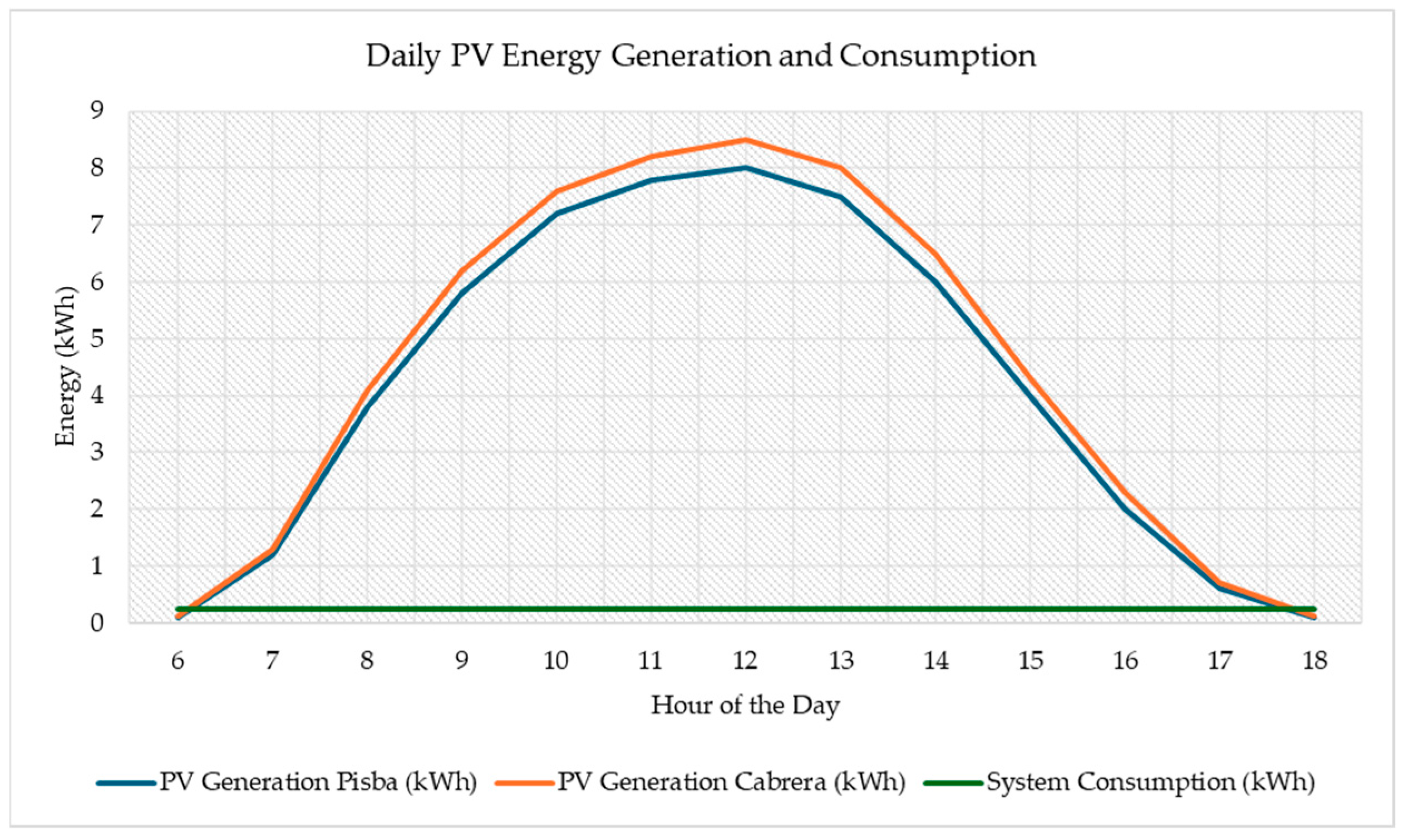

Section 4): (i) daily profiles for typical days (e.g., the 15th of representative months), showing the pronounced midday peak in PV output; and (ii) monthly profiles across the year, evidencing seasonal variability driven by cloud cover, sun path, and tilt/orientation. These curves are time-aligned to the water-demand series from

Section 3.4 (resampled to 30 min resolution) to analyze energy–water coupling at sub-daily and monthly scales).

Also, in Colombia, surplus electricity from distributed generation projects can be sold to the grid under the framework of Law 1715 of 2014 and its regulatory decrees, which promote the integration of renewable energy into the national matrix. The Energy and Gas Regulatory Commission (CREG) has established specific guidelines, Resolution 174 of 2021 [

72] for grid interconnection and net billing (medición neta), enabling small-scale self-generators with renewable sources (≤1 MW) to inject surplus electricity into the distribution network. In rural electrification contexts, such as Pisba and Cabrera, this regulatory framework allows agrivoltaic projects to monetize surplus energy through credits applied to electricity bills or direct sales to local utilities (e.g., EBSA and ENEL-Codensa). These mechanisms not only ensure the economic viability of distributed solar projects but also strengthen the role of agrivoltaics in advancing Colombia’s rural energy transition and expanding access to clean energy.

3.6. Economic Analysis and WEFSCC Integration

The economic and systemic analysis of the agrivoltaic (AV) system integrated with vertical hydroponics was structured under a multidimensional evaluation framework based on the extended Water–Energy–Food–Soil–Climate–Communities (WEFSCC) nexus. This approach simultaneously incorporates technical, financial, social, and environmental indicators, allowing for an integrated assessment of resource interdependencies and resilience in vulnerable rural contexts [

8,

9]. The analysis goes beyond conventional return-on-investment methodologies by capturing synergies among productive efficiency, renewable energy generation, and social inclusion within post-conflict territories.

3.6.1. Boundary Conditions and Model Structure

The methodological design was implemented in a five-year dynamic cash flow model, developed in Microsoft Excel and parameterized with technical outputs from

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5. It integrates hydroponic production performance, photovoltaic (PV) energy generation, and socio-economic indicators to simulate the systemic behavior of the AV unit (“Productive Unit”, PU). The boundary conditions defining the model are summarized below:

Climatic parameters:

Hourly series of solar irradiance, air temperature, and precipitation were obtained from IDEAM datasets, ensuring spatial representativeness for Pisba and Cabrera. Interannual variability of ±10–15% was used to represent climate uncertainty and to define upper and lower radiation limits for scenario evaluation.

Agricultural parameters:

Crop selection and yields were based on

Section 3.3, considering phenological cycles, water-use efficiency (WUE), and the hydroponic recovery factor (ηr = 0.80–0.95). Nutrient solution losses, replacement frequency, and crop turnover rates were included to represent operational dynamics under variable radiation and temperature conditions [

36].

Energy parameters:

PV generation capacity was fixed at 30 kWpDC, using a performance ratio (PR) of 0.79 derived from

Table 1. The energy subsystem inputs included hourly irradiance (GPOA), temperature-adjusted module performance, and grid interconnection conditions following Law 1715 of 2014 and CREG Resolution 174 2021 [

72]. Daily and annual generation curves were synchronized with water-demand cycles to analyze energy–water interactions within the WEFSCC model [

35,

53,

55].

Economic and financial parameters:

The model incorporated investment (CapEx) and operation (OpEx) costs, including PV panels, inverters, structural components, hydroponic towers, and recirculation systems. Revenue streams included agricultural sales and surplus energy commercialization through net billing mechanisms. Key indicators are Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Payback Period, selected as primary financial outputs [

13]. Sensitivity analyses were performed for discount rate, electricity tariff, equipment lifespan, and agricultural yields [

28].

3.6.2. Scenario Configuration

Three simulation scenarios, conservative, moderate, and optimistic, were established to capture uncertainty in climatic, technical, and market conditions, ensuring a robust evaluation of system adaptability and resilience. These scenarios vary key parameters across environmental, technical, and financial dimensions, as summarized in

Table 3.

Basis for scenario ranges. The conservative–moderate–optimistic bands reflect observed and documented variability and uncertainty in the coupled agro-PV system and local markets. Solar irradiance was varied at −15%/mean/+10% to bracket interannual fluctuations in Andean sky conditions derived from the IDEAM time series used in the model (

Section 3.5). The performance ratio (PR 0.75/0.79/0.83) follows the component-loss budget in

Table 1 and published PR spreads for fixed-tilt systems of similar size under tropical conditions, accounting for temperature, soiling, mismatch, wiring, inverter efficiency, availability, and agri-shading. Hydroponic recovery efficiency (ηr 0.80/0.90/0.95) and crop yields (−20%/base/+15%) reflect (i) measured ranges for recirculating NFT systems and (ii) uncertainty in RUE-based yield under partial shade (transmissivity, temperature) for lettuce, spinach, and strawberry (

Section 3.3). Financial levers (CapEx ±15/−10%, OpEx +10/−5%) capture supplier quotation dispersion and O&M intensity in rural settings; discount rates (10/8/6%) span typical hurdle rates for agri-energy community projects; tariffs (0.07/0.09/0.11 USD·kWh

−1) represent plausible rural net-billing bands under Colombia’s distributed generation framework referenced in

Section 3.5. These ranges are thus traceable to the datasets, equipment specifications, and operating conditions documented in

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5, while ensuring robustness via sensitivity to the main physical and economic drivers.

3.6.3. Analytical Approach and Sensitivity Structure

Each scenario was executed under identical computational conditions, ensuring consistent comparison among results. Climatic, agronomic, and financial variables were varied parametrically to evaluate system performance and vulnerability. The conservative scenario represents unfavorable environmental and market conditions (reduced irradiance, lower yields, and higher costs), while the optimistic scenario simulates enhanced performance due to favorable climatic conditions and community engagement. The moderate scenario serves as the baseline configuration, corresponding to the mean historical conditions of both municipalities. The model applies a sensitivity analysis on critical variables (solar radiation, hydroponic efficiency, CapEx, OpEx, and discount rate) to quantify the marginal effect of parameter variation on financial and environmental indicators.

3.6.4. Integration Within the WEFSCC Framework

The three simulation scenarios enable the evaluation of multidimensional feedbacks among WEFSCC components: (i) Water–Energy: coupling between hydroponic recirculation cycles and PV generation profiles, ensuring system self-sufficiency. (ii) Energy–Climate: influence of radiation variability and temperature on PV output and overall performance ratio. (iii) Food–Soil: variation in yield efficiency and nutrient uptake under changing microclimatic conditions. (iv) Communities–Economy: local participation in system operation and energy monetization through cooperative schemes, improving territorial income distribution. (v) From the social dimension, each array of productive units (PU) is projected to generate approximately nine permanent jobs (production, operation, maintenance, commercialization), fostering inclusion of women and youth in local agricultural value chains [

22,

57]. (vi) From the environmental dimension, indicators include the reduction in water footprint, decrease in fossil fuel emissions, and land-use efficiency through dual productivity (energy and food) on the same surface, contributing to soil conservation and ecosystem restoration [

3,

73].

Finally, integrating these outcomes within the WEFSCC framework supports a systemic perspective of agrivoltaics as a resilient strategy for sustainable land management in post-conflict rural regions, linking climate adaptation, social reintegration, and economic viability [

2,

30,

31].

3.7. Load Analysis

The structural assessment of the photovoltaic (PV) support tower was carried out to validate its mechanical stability under operational and extreme load conditions, ensuring compliance with Colombian and international design standards for light agro-industrial structures. The tower, hereafter referred to as the Productive Unit (PU), consists of modular ABS components assembled around four Guadua (Guadua angustifolia Kunth) columns that provide vertical support and structural stiffness. Each tower integrates five circular layers of ABS modules—each composed of four interlocking panels—stacked to reach the total height of the hydroponic system, while the PV panel is mounted at the top, supported by the same guadua framework (

Figure 4).

The load analysis followed a finite element analysis (FEA) approach using Autodesk Inventor® 2024 with the FEA module, applying both static and dynamic simulations to determine the system’s stress distribution, displacement fields, and global safety factor (FS). The procedure consisted of defining the total acting forces on the tower (dead, live, wind, and operational loads) and distributing them among the five modules and four columns that constitute the base structure. The boundary conditions were defined to represent realistic support and environmental conditions: (i) Fixed constraints were applied at the column bases, replicating anchorage to the foundation plate. (ii) Gravity was included to account for the self-weight of structural components, hydroponic towers, and seedlings. (iii) External forces corresponded to wind pressure, hydroponic fluid loads, and the PV module weight. (iv) Contact and frictional constraints were implemented at the interfaces between ABS modules and guadua columns, ensuring appropriate load transfer.

For the ABS modules, mechanical properties were assigned directly from the software’s materials library (elastic modulus 2.3 GPa, yield strength 46 MPa, Poisson’s ratio 0.35). The Guadua angustifolia Kunth material was created as a custom orthotropic material following literature-reported properties (mean compressive strength 45 MPa, tensile strength 150 MPa, modulus of elasticity 12 GPa, density 730 kg m

−3). Progressive mesh refinement was performed until the variation in the safety factor (FS) between iterations was below 20%, following recommended convergence criteria for structural validation in agrivoltaic applications [

74]. The wind drag force acting on the tower and the solar module was calculated according to the standard aerodynamic formulation:

where

is the drag coefficient,

the air density,

A the projected area of the structure exposed to the wind (tower and solar panel with a 15° tilt), and

v the wind velocity. For this case, the worst expected load condition was considered, corresponding to a wind velocity of 10 m/s at ground level, consistent with maximum registered speeds in open-field rural zones such as La Guajira. The air density was assumed at 1.25 kg/m

3 (sea-level equivalent), and the drag coefficient

was adopted for the combined tower–panel geometry, following ASCE-7 and CFE wind loading recommendations for cylindrical and planar hybrid structures.

Table 4 summarizes the parameters used for the drag-force calculation.

The vertical loads include the self-weight of the structure (tower + PV module), hydroponic solution mass, and seedling biomass. The total static weight of the PV assembly was estimated at 706 N, distributed evenly across the four guadua columns. The hydroponic system load (water + plants) was estimated at 470.9 N, equivalent to 117.7 N per module, derived from the total mass of seedlings (48 kg). These values were used as service load conditions in the static FEA simulations (

Table 5).

The load combination (wind + gravity + live load) was applied under both serviceability and ultimate limit states. The simulations followed the recommendations of the Colombian Seismic Resistant Code (NSR-10) and the AISC Design Guide 33 for hybrid composite structures. Mesh density was increased iteratively until convergence in stress and displacement results was achieved, verifying mesh independence. The safety factor (FS) was evaluated according to:

where

is the yield strength of the material and

is the maximum stress obtained in the FEA simulation. Convergence was confirmed when the change in FS between consecutive runs was below 20%. This procedure ensures structural reliability under both operational and extreme environmental conditions.

From the Soil–Climate perspective of the WEFSCC nexus, the load analysis contributes to the evaluation of environmental resilience by ensuring that the structural design minimizes land disturbance, avoids soil compaction, and withstands extreme climatic events. The use of Guadua angustifolia, a renewable native material, reinforces sustainability principles by reducing embodied carbon and promoting circularity in rural construction [

8,

9]. Additionally, the tower design enhances community adaptability and local fabrication potential, allowing replication using regionally available materials and labor, consistent with the Communities component of the WEFSCC framework. The validation of structural performance under realistic loading conditions thus guarantees that the AV system not only achieves technical feasibility but also supports ecological and social sustainability in post-conflict territories.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study confirm the technical, economic, and socio-environmental feasibility of integrating agrivoltaic (AV) systems with hydroponic food production in Colombia’s post-conflict territories. By coupling renewable energy generation with intensive food cultivation under controlled water conditions, the proposed model demonstrates that dual land use can simultaneously enhance agricultural productivity, energy self-sufficiency, and local resilience. These findings reinforce the principles of the expanded Water–Energy–Food–Soil–Climate–Communities (WEFSCC) framework, which advocates for systemic optimization of resource flows across productive landscapes.

From a technical standpoint, the simulation of 30 kWpDC bifacial photovoltaic arrays in Pisba and Cabrera yielded an annual generation between 18 and 18 MWh, values consistent with comparable agrivoltaic pilots reported in Africa and southern Europe [

8,

9,

13]. The thermal–electrical modeling and hourly transposition of solar radiation to the plane of array (POA) provided a robust estimate of generation peaks and seasonal variability, validated against historical IDEAM radiation datasets. This outcome confirms that the Andean region offers adequate solar potential for small-scale distributed generation, even under partial cloudiness typical of mountain climates. Moreover, the alignment between modeled energy profiles and empirical patterns reported in similar latitudes by Refs. [

22,

75] supports the internal validity of the simulation results.

On the agricultural side, the hydroponic subsystem exhibited significant water-use efficiency (WUE) advantages, reducing total consumption by 70–80% compared to conventional open-field irrigation, while maintaining yields of 2.9 t ha

−1 for lettuce, 4.5 t ha

−1 for spinach, and 1.2 t ha

−1 for strawberry per production cycle. These results coincide with global evidence on the synergistic performance of AV–hydroponic integrations [

31,

55]. The controlled recirculation of nutrient solution, adjusted to daily evapotranspiration derived from FAO-56 Penman–Monteith [

36], demonstrated the capacity of the system to stabilize plant growth under reduced water input. Consequently, the AV configuration functions not only as a source of renewable energy but also as a microclimatic shield that mitigates water stress and increases photosynthetic efficiency, a key adaptation mechanism under ongoing climate change.

Financially, both municipalities displayed positive cash-flow trajectories and investment recoveries within five years, with unleveraged internal rates of return (IRRs) of 34.7% in Pisba and 42% in Cabrera. Sensitivity analysis across conservative, moderate, and optimistic scenarios revealed strong resilience to variations in crop price (±20%), yield (±15%), and tariff (±10%), confirming the robustness of the model to market and climatic uncertainty. These figures surpass standard profitability benchmarks for rural electrification projects and validate the hybrid AV–hydroponic model as a financially attractive pathway for decentralized renewable deployment in emerging economies.

From a social and environmental perspective, the pilots generated cumulative mitigation of ≈700 t CO2e over six years, in addition to the creation of five permanent jobs per site, with progressive inclusion of women and rural youth. The projects also achieved water self-sufficiency through rainwater harvesting systems that exceeded irrigation requirements by more than 200%, thereby reducing pressure on blue-water resources. Such outcomes position agrivoltaics as a multifunctional strategy that simultaneously advances clean energy, climate adaptation, and local employment—objectives central to Colombia’s Planes de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial (PDET) and Zonas Más Afectadas por el Conflicto (ZOMAC) frameworks.

Despite the strong quantitative performance, several limitations must be acknowledged. The results are based primarily on techno-environmental simulations and financial modeling; therefore, long-term empirical validation under real operating conditions remains essential. Future work should include continuous monitoring of energy generation, water dynamics, and crop productivity using IoT-based sensors and data loggers to assess seasonal variability and long-term reliability. Additionally, the inclusion of a life-cycle assessment (LCA) and socio-economic impact evaluation would further substantiate the sustainability claims of the system.

From a policy and governance standpoint, the evidence supports the formulation of specific agrivoltaic regulatory frameworks within Colombia’s renewable-energy and rural-development agendas. Recommended measures include: (i) fiscal incentives for dual-use land systems; (ii) streamlined environmental licensing for low-impact AV installations; (iii) concessional financing mechanisms through national green funds and international climate-finance programs (e.g., GCF, IDB); and (iv) technical-capacity programs to train local operators in agro-digitalization, hydroponic fertigation, and PV maintenance. For international development agencies, priority should be given to co-financing modular pilots in post-conflict municipalities, where agrivoltaic systems can catalyze local economies while strengthening peacebuilding and community resilience.

In conclusion, the integration of agrivoltaics with hydroponic agriculture represents a scalable, climate-resilient, and socially inclusive solution for sustainable land management in Colombia’s Andean regions. The synergy observed between water efficiency, renewable energy generation, and agricultural yield demonstrates the operational viability of the WEFSCC nexus as a guiding framework for rural innovation. By merging technological precision with social participation, the model bridges productivity and peace, providing a replicable blueprint for achieving national goals of energy transition, food security, and territorial cohesion in post-conflict settings.

Furthermore, the extrapolation of the obtained results toward other Cundinamarca municipalities with comparable agroclimatic profiles such as Nemocón, Tocancipá and Susa, underscores the scalability potential of the proposed agrivoltaic–hydroponic con-figuration. These areas exhibit similar elevations (≈2500–2600 m.a.s.l.), temperature regimes (12–14 °C), and bimodal precipitation patterns to those of Pisba and Cabrera, suggesting strong replicability of both the technical and economic performance demonstrated in this study. Within the framework of the project “Microgrids: energía flexible y eficiente para Cundinamarca” (BPIN: 2021000100523), such territorial extrapolation aligns with the funding objectives of promoting decentralized renewable generation and sustainable food systems through pilot expansion in regions with analogous resource dynamics and agricultural frontiers.

This extension positions agrivoltaics as a modular and regionally adaptable strategy for sustainable rural development in Colombia’s Andean corridor, reinforcing the role of science-based planning in guiding policy and investment decisions under departmental innovation programs.