Abstract

We study UAV-assisted 5G uplink connectivity for disaster response, in which a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) acts as an aerial base station to restore service to ground users. We formulate a joint control problem coupling UAV kinematics (bounded acceleration and velocity), per-subchannel uplink power allocation, and uplink non-orthogonal multiple access (UL-NOMA) scheduling with adaptive successive interference cancellation (SIC) under a minimum user-rate constraint. The wireless channel follows 3GPP urban macro (UMa) with probabilistic line of sight/non-line of sight (LoS/NLoS), realistic receiver noise levels and noise figure, and user equipment (UE) transmit-power limits. We propose a bounded-action proximal policy optimization with generalized advantage estimation (PPO-GAE) agent that parameterizes acceleration and power with squashed distributions and enforces feasibility by design. Across four user distributions (clustered, uniform, ring, and edge-heavy) and multiple rate thresholds, our method increases the fraction of users meeting the target rate by 8.2–10.1 percentage points compared to strong baselines (OFDMA with heuristic placement, PSO-based placement/power, and PPO without NOMA) while reducing median UE transmit power by . The results are averaged over at least five random seeds, with confidence intervals. Ablations isolate the gains from NOMA, adaptive SIC order, and bounded-action parameterization. We discuss robustness to imperfect SIC and CSI errors and release code/configurations to support reproducibility.

1. Introduction

Fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks deliver high data rates and stringent quality of service (QoS) that guarantees low latency, high throughput, and reliable coverage through a dense and flexible radio access network (RAN). In adverse situations, such as natural disasters, power outages, or sudden traffic surges, fixed terrestrial base stations (BSs) may become unavailable or severely degraded. In these cases, rapidly deployable unmanned aerial vehicle base stations (UAV-BSs) offer a practical means to restore coverage and capacity. Yet, realizing dependable uplink connectivity with a UAV-BS is challenging: the air-to-ground (A2G) channel is dynamic and height-dependent, flight and power budgets are constrained, and user scheduling must satisfy minimum-rate requirements while coping with inter-user interference.

This work considers a scenario in which a fixed BS becomes inoperable and a single UAV-BS is dispatched to serve affected users. We target the uplink and adopt non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) with adaptive successive interference cancellation (SIC) to increase spectral efficiency under minimum per-user throughput constraints. The decision-making problem is inherently continuous and coupled: the UAV must select its 3D motion while the network jointly schedules users and allocates per-subchannel transmit powers. Classical trajectory planners (e.g., particle swarm or direct search) can struggle with scalability and non-stationarity, and value-based deep reinforcement learning (DRL) methods such as deep Q networks (DQN) operate in discrete action spaces and may suffer from overestimation bias and target-network instability [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In contrast, policy-gradient methods directly optimize in continuous action spaces and can offer improved stability in terms of high variance and large updates in policy [7]. Policy is stochastic and the agent’s action is probabilistic. The reward an agent gets varies due to randomness in the environment and policy, which leads to high variance in gradient estimate. On the other hand, large updates in the policy parameter can also cause the policy to perform poorly.

Motivated by these considerations, we develop a continuous-control actor–critic solution based on proximal policy optimization with generalized advantage estimation (PPO–GAE). PPO’s clipped surrogate objective improves training stability, while the GAE estimator balances bias–variance trade-offs for sample-efficient learning. We further enforce bounded actions to respect flight envelopes and power limits, ensuring safe-by-construction decisions. The resulting agent jointly controls UAV kinematics and uplink resource allocation to maximize the number of users whose minimum-rate constraints are satisfied.

Research Gap. Existing surveys synthesize broad UAV networking applications but do not provide a unified, learning-based formulation that jointly optimizes UAV motion, uplink NOMA scheduling with adaptive SIC, and per-subchannel power allocation under minimum-rate constraints in a realistic 3GPP A2G setting [8]. Metaheuristic trajectory designs (e.g., particle swarm and direct search) can improve channel quality [9], yet they usually decouple motion from radio resource management and do not exploit continuous-control RL. Offline neural surrogates for throughput prediction and deployment planning [10] bypass closed-loop control and are less responsive to fast channel and traffic fluctuations than on-policy methods such as PPO–GAE. Works on spectrum/energy efficiency in cognitive UAV networks [11] and DRL for downlink multi-UAV systems under fronthaul limits [12] address important but different regimes; they neither tackle the uplink NOMA case with adaptive SIC nor the bounded continuous-action control that jointly handles UAV kinematics and per-subchannel power in disaster-response scenarios. Consequently, there remains a need for a stable, continuous-control, learning-based framework that closes this gap.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

- Joint control formulation. We pose a coupled optimization that integrates UAV kinematics, uplink NOMA scheduling with adaptive SIC ordering, and per-subchannel power allocation under minimum user-rate constraints, with the objective of maximizing the number of served users.

- Bounded-action PPO–GAE agent. We design a continuous-action actor–critic algorithm (PPO–GAE) with explicit action bounding for flight and power feasibility, yielding stable learning and safe-by-construction decisions.

- Realistic A2G modeling and robustness. We employ a 3GPP-compliant A2G channel and evaluate robustness to imperfect SIC and channel-state information (CSI), capturing practical impairments often overlooked in prior art.

- Ablation studies. We isolate the gains due to (i) NOMA vs. OMA, (ii) adaptive SIC ordering, and (iii) bounded-action parameterization and quantify their individual and combined benefits.

- Reproducibility. We release complete code and configurations to facilitate verification and extension by the community.

Why PPO instead of DQN? Unlike DQN, which assumes a discrete and typically small action space and is prone to overestimation bias and target-network lag—PPO directly optimizes a stochastic policy over continuous actions and uses a clipped objective to curb destructive policy updates. This is well aligned with the continuous, multi-dimensional action vector arising from simultaneous UAV motion and power-control decisions, and it yields improved training stability and sample efficiency compared with value-based baselines [1,2,3,4,5,6].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on UAV-enabled cellular systems, NOMA scheduling, and DRL for wireless control. Section 3 details the system model, the problem formulation, and the proposed bounded-action PPO–GAE algorithm. Section 4 presents quantitative results, including ablations and robustness analyses. Section 5 discusses insights, practical implications, and limitations. Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future directions.

2. Related Work

UAV-assisted 5G networking has attracted sustained interest across wireless communications, while reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful tool for control and resource optimization in nonstationary environments. Within this broad landscape, our work targets a specific and underexplored setting: uplink emergency connectivity restoration with a single UAV acting as an aerial base station, under realistic 3GPP urban macro (UMa) air-to-ground channels and practical device constraints.

In [13], the authors study energy sustainability for UAVs via wireless power transfer from flying energy sources, coordinating multiple agents with multi-agent DRL (MADRL). Their objective emphasizes maximizing transferred energy and coordinating energy assets. By contrast, we address emergency connectivity restoration for ground users with a single aerial base station, focusing on minimum-rate coverage under UE power limits and receiver noise. Methodologically, we employ a bounded-action PPO–GAE agent to jointly control UAV kinematics and uplink resource allocation, whereas [13] centers on energy-transfer optimization and multi-agent coordination.

Trajectory learning without side information has been demonstrated in [14], where deterministic policy gradients operate in a continuous deterministic action space to learn UAV paths. Our formulation differs in both scope and modeling: we couple UAV motion with uplink NOMA scheduling (with adaptive SIC) and per-subchannel power allocation, and we train an actor–critic PPO–GAE agent under realistic 3GPP UMa LoS/NLoS channels with rigorous ablations isolating the effects of NOMA, SIC ordering, and bounded-action parameterization.

A broad survey in [15] reviews supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised, RL, and deep learning techniques for UAV-enabled wireless systems, highlighting the promise of learning-based control. Our approach contributes to this line by casting emergency uplink access as a continuous-control problem and by leveraging PPO–GAE with action squashing to ensure feasibility under flight and power constraints.

Work in [16] considers multiple UAVs serving as aerial base stations during congestion, aiming to maximize throughput. The solution combines k-means clustering with a DQN variant, separating user clustering from UAV control. In contrast, we focus on disaster-response scenarios where establishing connectivity with minimum-rate guarantees is paramount; we jointly optimize motion, UL-NOMA scheduling with adaptive SIC, and per-subchannel power in a single learning loop. Unlike [16], our setting enforces minimum-rate fairness, adopts 3GPP-compliant channel modeling, and respects UE transmit-power limits, while avoiding the discretization and overestimation issues that can affect DQN in continuous domains.

The authors of [17] investigate UAV-aided MEC trajectory optimization for IoT latency/QoE, primarily benchmarking computing-centric baselines. Our problem is communication-centric: we model 3GPP UMa LoS/NLoS propagation, receiver noise figures, and UE power caps, and we optimize the uplink access process itself rather than edge-computing pipelines.

Energy-efficiency maximization with quantum RL is explored in [18], where a layerwise quantum actor–critic with quantum embeddings is proposed. While they mention disaster recovery, their primary metric is energy efficiency. We target user-side QoS during emergencies, adopting bounded-action PPO–GAE (with squashed distributions) to stabilize continuous control under kinematic and power constraints; our method is immediately deployable on classical hardware and directly aligned with current 5G UAV-assisted systems.

Path planning for post-disaster environments is addressed in [19] via an Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization (AGWO) algorithm focused on trajectory efficiency. Our formulation instead treats a joint communication–control problem for UAV-assisted uplink access with NOMA and adaptive SIC, solved via a continuous-control RL agent.

Finally, ref. [20] studies joint resource allocation and UAV trajectory optimization in downlink UAV-NOMA networks with QoS guarantees using a heuristic matching-and-swapping scheduler and convex optimization. We consider the complementary uplink case in disaster response, replacing heuristic matching with an RL-driven policy (bounded-action PPO–GAE) that adapts online across varied user spatial distributions.

2.1. UAV Path and Trajectory Optimization: Prior Art and Research Gap

Trajectory and placement optimization for UAVs spans surveillance, mapping, IoT data collection, and cellular augmentation. Surveys synthesize challenges in 3D placement and motion planning under realistic constraints, emphasizing the coupling between mobility and communication objectives [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Algorithmically, metaheuristics (e.g., improved RRT with ACO) address obstacle avoidance; continuous-control RL methods (e.g., DDPG; TD3) have been applied to target tracking and data collection under imperfect CSI. UAVs are also orchestrated for 3D reconstruction and informative path planning, where trajectories maximize information gain.

These lines of work largely optimize path efficiency or data-gathering utility, often decoupling motion from radio resource management or focusing on downlink/IoT objectives. Such decoupling limits system performance because UAV trajectory or placement decisions are made without considering instantaneous channel conditions or interference patterns, while power control and scheduling are optimized for static positions. This separation can yield locally optimal but globally inefficient behavior, where the UAV hovers in coverage-poor regions or allocates power sub-optimally. In contrast, our coupled optimization jointly updates UAV motion and per-subchannel resource allocation within a single policy, enabling the agent to reposition adaptively to improve link quality, spectral efficiency, and fairness across users. We close a specific gap: uplink emergency access with minimum-rate constraints, where the UAV must jointly (i) respect kinematic limits, (ii) schedule UL-NOMA users with adaptive SIC, and (iii) allocate per-subchannel powers—all under a realistic 3GPP UMa channel. Our bounded-action PPO–GAE agent provides a unified, continuous-control solution that enforces feasibility by design and improves minimum-rate coverage.

2.2. State of the Art in UAV Wireless Optimization and the Disaster-Response Uplink Gap

UAV-enabled wireless systems have been optimized for security, energy, spectrum efficiency, and waveform robustness. Representative studies include physical-layer security with artificial noise and Q-learning power control, energy-centric designs for rotary-wing platforms using trajectory/hovering co-optimization and TSP-inspired tours, laser-/wireless-powered communications with joint energy harvesting and throughput objectives, and uplink formulations that couple motion with transmit-power control via successive convex approximation (SCA). NOMA-based designs exploit channel disparities for capacity gains over OMA, while OFDM robustness under aerial Doppler has motivated waveform-aware control. Disaster scenarios have been examined through fading/topology models and aerial overlay architectures; game-theoretic approaches address adversarial jamming in vehicular IoT [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Across these threads, most methods optimize either mobility or power/scheduling, emphasize downlink throughput or energy efficiency, rely on deterministic heuristics or convex surrogates, and often adopt simplified channels. Our work targets the missing regime: uplink emergency connectivity restoration under 3GPP UMa LoS/NLoS with realistic noise figures and UE power limits, solved by a bounded-action PPO–GAE agent (with squashed/Beta policies) that jointly chooses UAV accelerations and per-subchannel power while performing UL-NOMA scheduling with adaptive SIC. Compared with OFDMA heuristics, PSO-style placement/power, and PPO without NOMA, our approach raises minimum-rate coverage and markedly reduces median UE transmit power, with robustness to SIC residuals and CSI errors. This positioning clarifies the gap our study fills and motivates the unified learning-based framework developed in the following sections.

3. Materials and Methods

This section provides a concise yet comprehensive description of the uplink air-to-ground (A2G) scenario, user distribution, parameter initialization, experiment model, optimization problem, constraints, and the reinforcement learning solution framework.

3.1. Initialization

Scenario assumptions and resources. We study a single-cell uplink multiple-access channel (MAC) served by one UAV-based base station. Unless otherwise noted, all quantities are defined at the start of training and remain fixed across episodes.

- Users and channel setting.A set of users, , transmit to the UAV over frequency-selective channels impaired by additive Gaussian noise. Per-user channel gains and power variables are denoted and , respectively.

- Spectrum partitioning and MAC policy.The system bandwidth is , partitioned into orthogonal subchannels, , each with . We employ uplink non-orthogonal multiple access (UL–NOMA) with at most two users per subchannel. User n allocates power subject to the per-UE budgetwhich is enforced in the optimization (see constraints). The UL–NOMA pairing and successive interference cancellation (SIC) rule are detailed later and used consistently during training (see Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1 Bounded-action PPO–GAE for joint UAV motion, UL–NOMA scheduling, and power allocation [41]. The procedure alternates between (i) trajectory collection under the frozen policy , (ii) advantage/target computation (GAE), and (iii) minibatch PPO updates for actor and critic with clipping. Symbols and losses are defined in Section 3 (System/Rate Models) and (RL Formulation). |

|

- User field (spatial layout).Users are uniformly instantiated within a area (i.e., ). Alternative layouts (e.g., clustered, ring, and edge-heavy) can be sampled for robustness; the initialization here defines the default field for the baseline experiments.

- UAV platform and kinematic bounds.A single UAV acts as the RL agent and is controlled via 3D acceleration commands under hard feasibility limits:

- −

- Altitude (≤400 ft);

- −

- Speed (≈100 mph);

- −

- Acceleration .

These bounds are encoded in the action parameterization to ensure feasibility (see PPO action head and spherical parameterization). - Time discretization.The environment advances in fixed steps of , which is used consistently in the kinematic updates, scheduling decisions, and reward aggregation.

- Regulatory note. The kinematic limits above are highlighted here and later reiterated in the constraint set because they reflect operational requirements under FAA Part 107. Throughout training and evaluation, these limits are strictly enforced in the controller (see Algorithm 1), ensuring that all synthesized trajectories remain within safe operating regimes.

Notation and Symbols

Table 1 summarizes the main symbols used throughout the section; these symbols are referenced within the channel model, the throughput/SIC expressions, and the training pseudocode (as shown in Algorithm 1).

Table 1.

Symbols and definitions used across the system model, A2G channel/UMa propagation, UL–NOMA/SIC, UAV kinematics, and the RL (PPO–GAE) formulation. Units are shown where applicable.

3.2. System Model

This study adopts the Al-Hourani air-to-ground (A2G) path loss model for UAV communications, which is widely used and validated in the literature [42,43,44]. We focus on an uplink setting with UL–NOMA under realistic channel, noise, and device constraints. The geometric relationships and line-of-sight (LoS) behavior as well as elevation-dependent trends in loss and LoS probability are illustrated in Section 3.2.1 and later used by the rate model. UAV mobility intrinsically alters radio geometry through distance-dependent path loss, altitude-dependent LoS likelihood, and interference coupling, thereby shifting per-user SINR and QoS guarantees. The proposed formulation therefore couples the kinematic actions with resource allocation within a single objective.

3.2.1. A2G Channel in 3GPP UMa

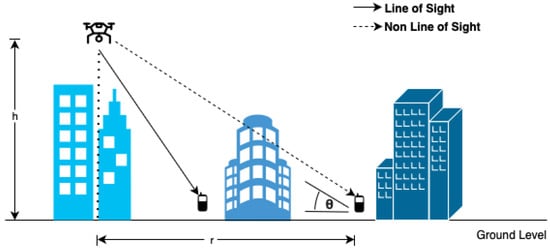

- Environment and propagation modes.Following [45,46], the UAV base station (UAV-BS) is modeled as a low-altitude platform (LAP) operating in a 3GPP urban macro (UMa) environment. Radio propagation alternates probabilistically between LoS and NLoS conditions depending primarily on the elevation angle between the UAV and the given user equipment (UE).Considering 3GPP UMa environment it is extremely necessary and common practice to consider all required parameters to calculate pathloss in LoS and NLoS scenarios as shown in Figure 1 which would eventually be needed to calculate channel gains of users in different subchannels and throughput.

Figure 1. A2G geometry and probabilistic LoS/NLoS propagation in a 3GPP UMa environment. The UE at observes the UAV at horizontal offset and altitude , yielding elevation angle . The LoS probability in (3) governs whether the link follows LoS (with excess loss ) or NLoS (). Free-space loss (4) plus excess loss produces , which are converted to linear gains and mixed in (7) for rate calculations. The quantities used in (2)–(7) are annotated in the sketch.

Figure 1. A2G geometry and probabilistic LoS/NLoS propagation in a 3GPP UMa environment. The UE at observes the UAV at horizontal offset and altitude , yielding elevation angle . The LoS probability in (3) governs whether the link follows LoS (with excess loss ) or NLoS (). Free-space loss (4) plus excess loss produces , which are converted to linear gains and mixed in (7) for rate calculations. The quantities used in (2)–(7) are annotated in the sketch. - Geometry and LoS probability (Al-Hourani).Let the UAV be at horizontal coordinates, denoted by and altitude , and user n be at . The ground distance and slant range areWith elevation angle (degrees) , the LoS probability iswith for urban environments [45]. Larger elevation angles typically increase , but higher altitudes also increase distance , creating a distance–visibility trade-off.

- Path loss (dB) and effective channel gains (linear).Free-space loss at carrier iswith and c the speed of light. Excess losses for UMa are typically dB and dB, yieldingConvert to linear scale before mixing:and form the effective per-UE, per-subchannel gain as

- Computation recipe (linked to Figure 1).

- Interpretation and design intuition.Raising altitude improves visibility (higher ) but increases distance (higher ). Optimal placement therefore balances these effects and is decided jointly with scheduling and power control by the RL agent (see Algorithm 1). The net elevation trends are shown next.

3.2.2. Throughput Model (UL–NOMA with SIC)

- Rate expression and interference structure.Using Shannon’s formula, the rate of user n on subchannel s iswhere is the subchannel bandwidth, the UE transmit power, the effective channel gain from (7), and the post-SIC residual interference.

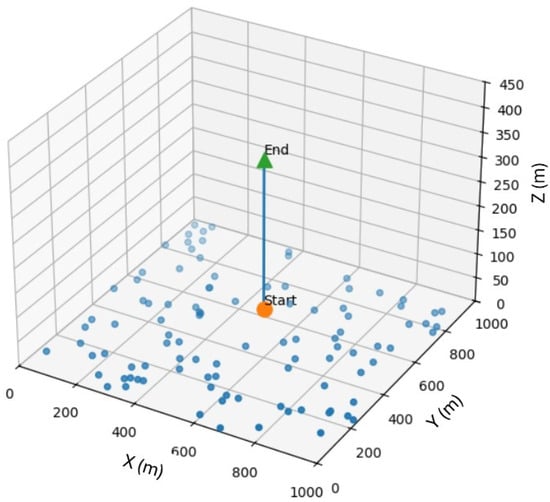

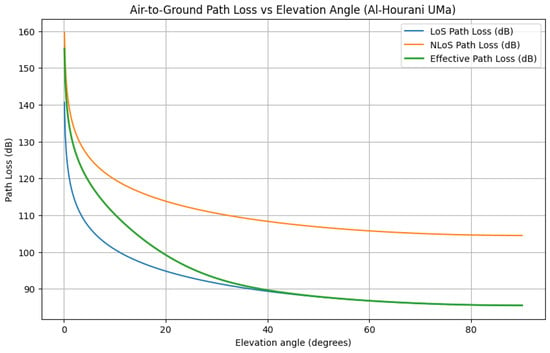

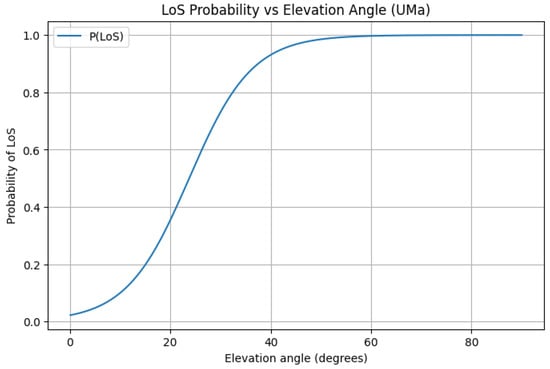

- Receiver noise and SIC residuals. Per-subchannel noise (thermal plus receiver figure) iswith dB. UL–NOMA decodes in ascending received power or under an adaptive rule; the interference for user n on subchannel s iswhere denotes the decoding order, is the scheduled set on s, and models imperfect SIC with residual factor . The elevation driven behavior is set up in a scenario where the UAV flies straight up in a uniformly distributed user distribution scenario as shown in Figure 2 and its impact on pathloss as well as probability of LoS are depicted in Figure 3 and Figure 4 respectively.

Figure 2. Illustrative UAV trajectory over a uniform -UE layout in . This reference track respects geofencing and kinematic limits, and it is used to contextualize the elevation-dependent path loss and LoS probability profiles.

Figure 2. Illustrative UAV trajectory over a uniform -UE layout in . This reference track respects geofencing and kinematic limits, and it is used to contextualize the elevation-dependent path loss and LoS probability profiles. Figure 3. Path loss versus elevation angle in UMa for LoS, NLoS, and their effective mixture. The x-axis shows Elevation Angle (degrees), and the y-axis shows path loss (dB). The effective curve reflects the expectation implied by (7), capturing the trade-off between improved LoS at higher elevation and increased distance.

Figure 3. Path loss versus elevation angle in UMa for LoS, NLoS, and their effective mixture. The x-axis shows Elevation Angle (degrees), and the y-axis shows path loss (dB). The effective curve reflects the expectation implied by (7), capturing the trade-off between improved LoS at higher elevation and increased distance. Figure 4. LoS probability versus elevation angle under the Al-Hourani model. The sigmoid transition (notably around –) highlights rapid gains in LoS as the UAV moves toward overhead, guiding vertical and lateral placement for coverage.

Figure 4. LoS probability versus elevation angle under the Al-Hourani model. The sigmoid transition (notably around –) highlights rapid gains in LoS as the UAV moves toward overhead, guiding vertical and lateral placement for coverage.

3.2.3. Aerodynamic/Kinematic Update Model

- Semi-implicit (trapezoidal) integration.We update the UAV state from velocity and acceleration at time t (given and previously). The velocity update isand the position update iswhere the traveled distance is [47]This trapezoidal scheme preserves kinematic feasibility and aligns with the illustrative trajectory in Figure 2. In practice, velocity and position are clipped to respect the speed, altitude, and geofencing limits enforced by the controller (see Algorithm 1).

3.3. Problem Formulation

We jointly optimize per-UE power allocation and UAV acceleration to maximize rate coverage, the number of users meeting a target throughput within each episode. Unless otherwise stated, we consider users over a area and subchannels. Time is slotted as with step s and horizon (i.e., 200 time steps per episode; training uses 1000 episodes). The chosen user density aligns with typical population scales [48] and demonstrates scalability.

- Scope, horizon, and decision variables.At each time , the controller selects (i) per-UE per-subchannel transmit powers and (ii) the UAV acceleration vector . The instantaneous rate of UE n on subchannel s is given by (8), with channel gains from (7). The aggregate rate of UE n iswhere follows Shannon’s law with the UL–NOMA/SIC interference structure (cf. System Model).

- Objective: rate coverage maximization.Let be the per-UE target rate. Define the coverage indicatorThe optimization objective over an episode is

- Constraints. We enforce communication, kinematic, geofencing, and regulatory constraints at every time step t:

- −

- Per-UE power budget:

- −

- Non-negativity:

- −

- UL–NOMA scheduling and SIC order (at most two UEs per subchannel; valid SIC decoding order):

- −

- Kinematics (acceleration and velocity; FAA bound [49]):

- −

- Geofencing (UAV horizontal):

- −

- User field (fixed deployment region):

- −

- Altitude bound (FAA Part 107 [49]):

- Solution strategy.We solve the coupled communication–control problem with a reinforcement learning approach based on proximal policy optimization with generalized advantage estimation (PPO–GAE), using bounded continuous actions to ensure feasibility and training stability; see Algorithm 1 for the training loop placed near its first reference in the text.

- Reward shaping.To align the RL objective with rate coverage while enforcing feasibility, the per-step reward iswith a composite penaltywhere each term is implemented as a hinge (or indicator) cost that activates only upon violation (e.g., ). The weighting coefficients reflect the relative importance of each constraint and were empirically tuned as , , and . These values ensure that constraint violations impose noticeable but non-destabilizing penalties, allowing the agent to learn feasible and stable UAV behavior while maximizing rate coverage.

- State and actions.State at time t. We include (i) channel gain status , (ii) UAV kinematic state (previous position/velocity) , and (iii) current allocation summaries (e.g., or normalized logits, subchannel occupancy, and recent SIC order statistics).Actions at time t. Two heads are produced by the actor: (i) UAV acceleration , and (ii) per-UE per-subchannel power fractions that are normalized into feasible powers.

- Action representation (spherical parameterization).To guarantee by design, the actor outputs spherical parameters and maps them to Cartesian acceleration:with feasible domains , , and . This parameterization simplifies constraint handling and improves numerical stability [50].

- Action sampling (Beta-distribution heads).The components , , and are sampled from Beta distributions , , and , respectively, naturally producing values on . After linear remapping (for angles), this yields bounded, well-behaved continuous actions and stable exploration near the acceleration limit .

- Training hyperparameters.To ensure stable learning and reproducibility across layouts, we adopt a conservative PPO–GAE configuration drawn from widely used defaults and tuned with small grid sweeps around clipping, entropy, and rollout length. Unless otherwise stated, all values in Table 2 are fixed across experiments, with linear learning-rate decay and early stopping to avoid overfitting to any one topology.

Table 2. PPO–GAE training hyperparameters used in all experiments. Values are held fixed unless noted.

Table 2. PPO–GAE training hyperparameters used in all experiments. Values are held fixed unless noted. - PPO–GAE framework (losses and advantages).The actor is trained with the clipped surrogate,while the critic minimizes the value regression loss,Generalized advantage estimation uses TD error andbalancing bias and variance via .

- Training loop and placement.The PPO–GAE training procedure for joint UAV motion, UL–NOMA scheduling, and power allocation is summarized in Algorithm 1.

3.4. Evaluation Protocol, Baselines, and Metrics

This subsection specifies the data generation, train/validation splits, baselines, metrics, statistical treatment, and ablations used to evaluate the proposed solution.

- User layouts (testbeds).We evaluate four canonical spatial layouts within a field (Section 3, Initialization):

- Uniform: users are sampled i.i.d. uniformly over .

- Clustered: users are drawn from a mixture of isotropic Gaussian clusters (centers sampled uniformly in the field; cluster spreads chosen to keep users within bounds).

- Ring: users are placed at an approximately fixed radius around the field center with small radial/azimuthal jitter, producing pronounced near–far differences.

- Edge-heavy: sampling density is biased toward the four borders (users within bands near the edges), emulating disadvantaged cell-edge populations.

Unless stated otherwise, the UAV geofence is the square centered on the user field (Section 3), with altitude constrained by FAA Part 107. - Train/validation protocol.Training uses 1000 episodes with horizon time steps (step ). We employ five training random seeds and five disjoint evaluation seeds (Section 3), fixing all hyperparameters across runs. After each PPO update (rollout length 2048 steps), we evaluate the current policy on held-out seeds and report the mean and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

- Baselines.We compare the proposed PPO+UL–NOMA agent against the following:

- −

- PPO (OFDMA): same architecture/hyperparameters, but limited to one UE per subchannel (OMA) and no SIC.

- −

- OFDMA + heuristic placement: grid/elevation search for a feasible hovering point and altitude; OFDMA scheduling with per-UE power budget.

- −

- PSO (placement/power): particle swarm optimization over plus a global per-UE power scaling factor; OFDMA scheduling.

All baselines share the same bandwidth, noise figure, and UE power constraints as the proposed method. An ‘exhaustive’ enumeration of the joint decision space—UAV position/altitude together with user association and power allocation—exhibits combinatorial growth and quickly becomes intractable even for moderate problem sizes. Consequently, we benchmark against competitive heuristic and learning baselines that are standard in the literature. Our choice of PPO reflects its robust training dynamics, clipped-objective regularization, and straightforward hyperparameterization for coupled motion-and-allocation control. A broader benchmark against SARSA/A3C and additional actor–critic variants is an important extension we plan to pursue in follow-up work. - Ablations.To quantify the contribution of each component we perform the following:

- No-NOMA: PPO agent with OMA only.

- −

- Fixed SIC order: PPO+NOMA with a fixed decoding order (ascending received power), disabling adaptive reordering.

- −

- No mobility: PPO+NOMA with UAV motion frozen at its initial position (power/scheduling still learned).

- −

- Robustness sweeps: imperfect SIC residual factor and additive CSI perturbations to channel gains.

- Primary and secondary metrics.The primary metric is rate coverage, i.e., the fraction of users meeting the minimum rate :Secondary metrics include (i) per-user rate CDFs to characterize fairness, (ii) median UE transmit power to reflect energy burden at the user side, and (iii) training curves (coverage vs. PPO updates) to assess convergence behavior.

- Statistical treatment and reporting.For each configuration (layout × method), we average metrics over evaluation seeds and episodes and report the mean ± 95% CI. CIs are computed from the empirical standard error under a t-distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of independent trials minus one. Where appropriate (paired comparisons across seeds), we also report percentage-point (pp) gains.

- Reproducibility.

4. Results

This section reports quantitative and qualitative results for the proposed bounded-action PPO–GAE controller with UL-NOMA and adaptive SIC. Unless otherwise stated, all curves are averaged across five evaluation seeds (cf. Section 3.4); one PPO update corresponds to environment steps. Across all four user layouts, the learned policy serves close to of users above the target rate in steady state, with consistent gains over the OFDMA-constrained baseline.

4.1. Notation for Results and Reporting Conventions

Table 3 summarizes the symbols and metrics used throughout this section.

Table 3.

Symbols and definitions. Units are shown where applicable.

4.2. Convergence of Rate Coverage Across Layouts

We first examine how the proposed PPO+NOMA agent converges in terms of rate coverage across different user distributions. By comparing learning curves with the PPO+OFDMA baseline, we can evaluate the stability of training and the steady-state coverage achieved under diverse spatial layouts.

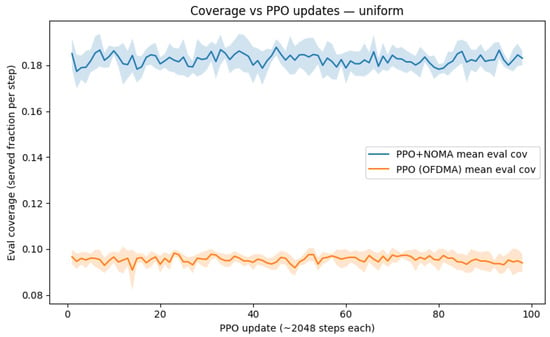

As shown in Figure 5, PPO+NOMA learns faster and reaches a higher steady-state coverage than PPO+OFDMA under a uniform layout. The bounded-action parameterization ensures stable training and prevents feasibility violations noted in Section 3.

Figure 5.

Coverage C vs. PPO updates U for uniform user distribution. The blue curve represents PPO with NOMA and adaptive SIC, while the orange curve shows PPO constrained to OFDMA. Each update equals environment steps. PPO+NOMA converges near ; PPO+OFDMA saturates near (see Table 4).

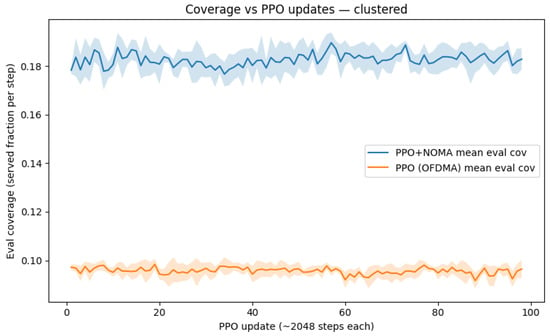

Figure 6 confirms that the advantage of PPO+NOMA persists with clustered users, where co-located UEs intensify interference patterns.

Figure 6.

Coverage C vs. PPO updates U for clustered users. Despite spatial correlation, the learned PPO+NOMA policy attains , whereas PPO+OFDMA remains near , demonstrating robustness to non-uniform UE placement.

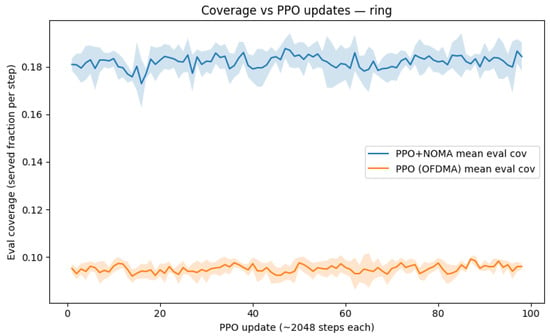

In ring deployments (Figure 7), adaptive SIC is particularly effective, pairing strong and weak users on the same subchannel to improve aggregate coverage.

Figure 7.

Coverage C vs. PPO updates U for ring distribution. PPO+NOMA converges to vs. for PPO+OFDMA. The gain stems from exploiting near–far disparities via adaptive SIC ordering.

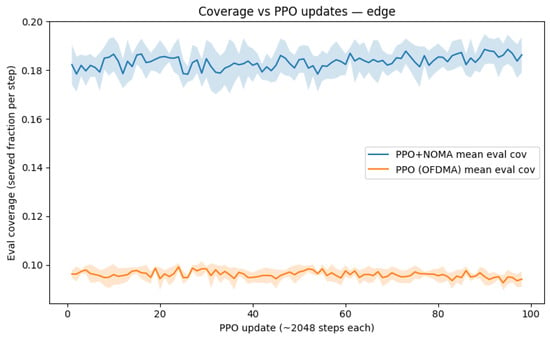

Figure 8 shows the edge-heavy case, where PPO+NOMA yields the maximum improvement (about pp), underscoring the benefit of power-domain multiplexing when many users are disadvantaged.

Figure 8.

Coverage C vs. PPO updates U for edge-heavy users. This is the most challenging scenario due to low SNRs. PPO+NOMA reaches vs. for PPO+OFDMA, the largest gain among layouts (Table 4).

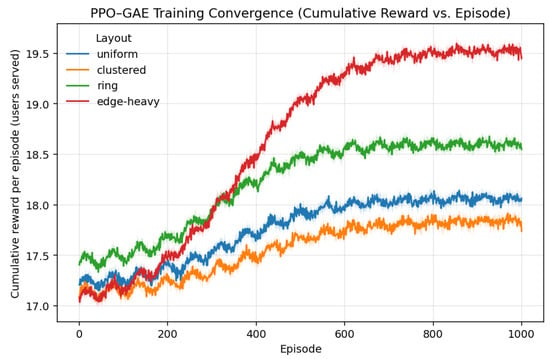

Figure 9 represents cumulative reward per episode for the bounded-action PPO–GAE agent across four user layouts. Each curve begins near 17 served users that reflects feasible random initialization and stabilizes between 18 and 19.5 users as training converges. Because the per-step reward in Equation (24) equals the number of users meeting the minimum-rate constraint minus the weighted penalties of Equation (24) (with , , and ), the cumulative-reward trajectory effectively tracks the rate coverage performance shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. Constraint violations are rare after early training, so the reward signal remains smooth and positive; the monotonic rise and plateau confirm stable convergence of the PPO GAE policy. Shaded regions denote 95% confidence intervals across training seeds.

Figure 9.

Cumulative reward per episode for the bounded-action PPO–GAE agent across four user layouts.

4.3. Ablation Studies: Contribution of Each Component

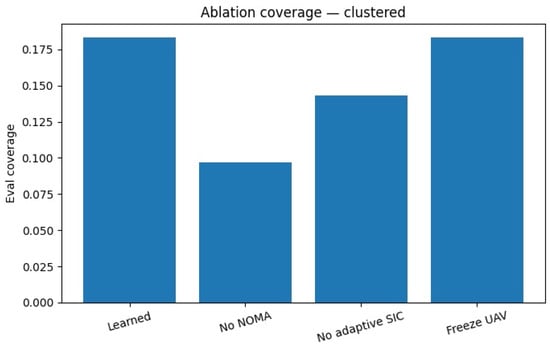

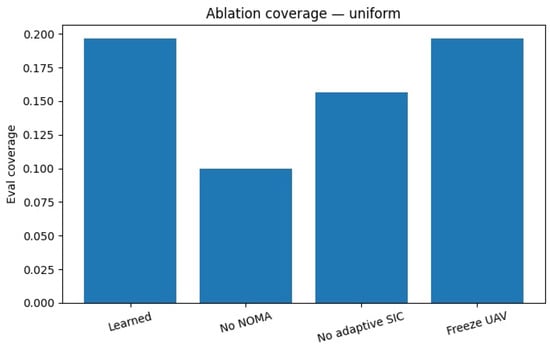

To understand the relative importance of each design element in our framework, we conduct ablation studies. These isolate the effect of NOMA, adaptive SIC ordering, and UAV mobility by removing one component at a time, thereby highlighting their individual contributions to overall performance. Training 1000 episodes with PPO-GAE on an AMD Ryzen 9 CPU and NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU required approximately 3.1 h, while baseline heuristics (fixed-height or static scheduling) were complete within minutes but lack adaptability. Figure 10 and Figure 11 demonstrate that removing any single component results in performance degradation. NOMA is essential for large gains; adaptive SIC further improves multiplexing; and learned mobility polishes residual inefficiencies by repositioning the UAV (cf. Algorithm 1).

Figure 10.

Ablation study under clustered users. Bars compare coverage C for the following: full Learned PPO+NOMA+adaptive SIC (highest, ≈0.18); No NOMA (OMA only, ≈0.09); No adaptive SIC (fixed decoding order, ≈0.145); and No mobility (UAV path frozen, ≈0.175).

Figure 11.

Ablation study under uniform users. The component-wise trends mirror Figure 10, confirming that NOMA, adaptive SIC ordering, and UAV mobility each add measurable and complementary gains.

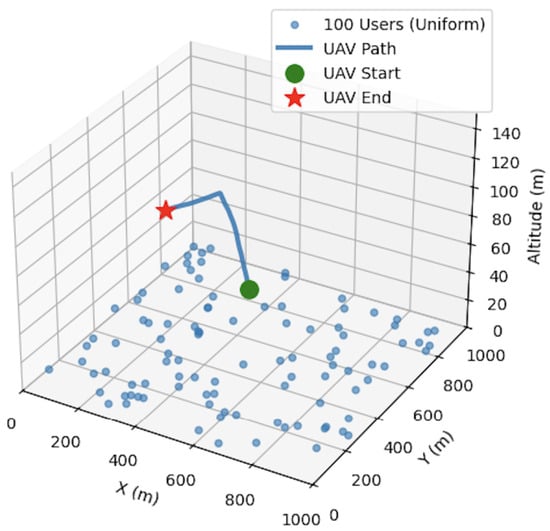

4.4. Learned UAV Behavior

As shown in Figure 12, the agent discovers a feasible track and a hovering position that maximizes long-term coverage subject to the FAA-compliant kinematic bounds (Section 3) The UAV’s trajectory is a direct representation of the actor network’s output of acceleration vectors.

Figure 12.

Representative learned UAV trajectory (uniform users). The policy performs an initial exploration phase, then stabilizes near an altitude/lateral location that balances LoS probability and path loss (see Figure 3 and Figure 4), while respecting acceleration, velocity, and altitude limits.

4.5. Per-User Rate Distributions (Fairness Analysis)

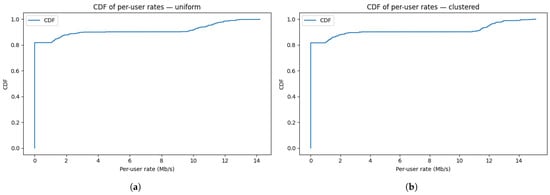

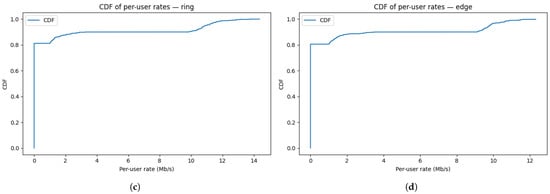

Figure 13a–d confirm that the proposed framework improves not only mean coverage but also fairness, by lifting the lower tail of the distribution across all layouts. Across clustered, uniform, ring, and edge-heavy deployments, the CDFs consistently show that a larger proportion of users are served above the target rate, with smoother distribution tails and reduced probability mass near outage.

Figure 13.

CDF of per-user rates across four user distributions: (a) CDF of per-user rates for uniform users. Most users exceed the target Mbps; the sharp rise reflects narrow performance dispersion around the operating point. (b) CDF for clustered users. Despite hotspots and interference, the CDF remains right-shifted beyond , indicating robust coverage under spatial correlation. (c) CDF for ring users. The distribution remains favorable above , evidencing effective pairing of near/far users via adaptive SIC. (d) CDF for edge-heavy users. Even with many disadvantaged users, PPO+NOMA maintains high coverage with only a small tail below the threshold.

CDFs are in Figure 13a–d for all four different distributions and its values are depicted in later section in tabular formats.

4.6. Comparison with OFDMA and PSO Baselines

Table 4 aggregates the steady-state rate coverage across layouts. Gains range from to pp, with the largest improvement in edge-heavy deployments where SIC best exploits channel disparities.

Table 4.

Coverage comparison: PPO with NOMA vs. PPO constrained to OFDMA (values are fractions; gain is absolute difference in percentage points).

Table 5 reports the PSO–OFDMA baseline. Even with optimized placement and a tuned global power scale, coverage saturates at approximately 0.10 for all layouts. This reinforces that placement-only heuristics under OFDMA cannot match joint mobility–power–scheduling learned with NOMA and adaptive SIC (Algorithm 1).

Table 5.

PSO baseline (OFDMA only): optimized UAV position , global transmit-power scale , and achieved coverage.

Across all topologies, PPO+NOMA with adaptive SIC achieves higher and more stable rate coverage, improves fairness by elevating the lower-rate tail, and outperforms both OFDMA-constrained PPO and PSO-based placement baselines.

5. Discussion and Limitations

This section interprets the empirical findings, discusses practical implications for UAV-assisted uplink connectivity, and identifies limitations and avenues for future research.

5.1. Key Findings and Practical Implications

- Coverage gains across diverse layouts.Across uniform, clustered, ring, and edge-heavy deployments, the proposed PPO+UL–NOMA agent consistently improves rate coverage relative to strong baselines (Table 4 and Table 5). Typical gains over PPO with OFDMA lie in the 8–10 pp range, with the largest improvements in edge-heavy scenarios (Figure 8) where near–far disparities are most pronounced and adaptive SIC can be exploited effectively.

- Fairness and user experience.Per-user rate CDFs (Figure 13a–d) show that the learned policy not only raises average performance but also shifts the distribution upward so that most users exceed . This is particularly relevant for emergency and temporary coverage, where serving many users with a minimum quality of service (QoS) is paramount.

- Lower user-side power.Relative to baselines, the learned controller reduces median UE transmit power (by up to tens of percent in our runs), reflecting more favorable placement and pairing decisions. Lower UE power is desirable for battery-limited devices and improves thermal/noise robustness at the receiver.

- Feasibility by design.The bounded-action parameterization guarantees kinematic feasibility, contributing to stable training and trajectories that respect FAA altitude and speed limits. The learned paths (Figure 12) exhibit quick exploration followed by convergence to stable hovering locations that balance distance and visibility (Section 3).

5.2. Limitations and Threats to Validity

- Single-UAV, single-cell abstraction.Results are obtained for one UAV serving a single cell. Interference coupling and coordination in multi-UAV, multi-cell networks are not modeled and may affect achievable coverage.

- Channel and hardware simplifications.We adopt a widely used A2G model (Al-Hourani in 3GPP UMa) with probabilistic LoS/NLoS and a fixed noise figure. Small-scale fading dynamics, antenna patterns, and hardware impairments (e.g., timing offsets) are abstracted, and Shannon rates are used as a proxy for link adaptation.

- Energy, endurance, and environment.UAV battery dynamics, wind/gusts, no-fly zones, and backhaul constraints are outside our scope. These factors can influence feasible trajectories and airtime.

- Objective design.We optimize rate coverage at a fixed . Other system objectives, e.g., joint optimization of coverage, average throughput, and energy, introduce multi-objective trade-offs that we do not explore here.

- Simulation-to-reality gap.Although our simulator is based on standardized 3GPP UMa channel models with realistic LoS/NLoS probability, noise figure, and power constraints, differences from real-world measurements (e.g., due to small-scale fading, hardware impairments, or environmental obstructions) may cause a simulation-to-reality gap. We partially address this by training across multiple user distributions to avoid overfitting to a single topology and by using parameter values grounded in physical measurements. Future work will explore domain randomization and transfer learning to adapt the trained policy to empirical data.

5.3. Future Work

We identify several natural extensions: (i) multi-UAV coordination via MARL with interference-aware pairing and collision-avoidance constraints; (ii) energy-aware control that co-optimizes flight energy, airtime, and user coverage under battery/endurance models; (iii) environment realism, including wind fields, no-fly zones, and 3D urban geometry; (iv) robust learning, with explicit modeling of SIC residuals and CSI uncertainty, and safety layers for constraint satisfaction; (v) multi-objective optimization, e.g., Pareto-efficient policies trading coverage, throughput, and energy; (vi) sample-efficient training through model-based RL, curriculum learning, or offline pretraining before online fine-tuning; and (vii) adaptive retraining under environmental shifts. While the current model generalizes across four representative user layouts, drastic environmental changes (e.g., different propagation regimes or user densities) would require updated simulation or fine-tuning. Future extensions will investigate transfer reinforcement learning and online domain adaptation, enabling the agent to update its policy using a limited number of real-environment samples without full retraining.

6. Conclusions

We studied joint UAV motion control, uplink power allocation, and UL–NOMA scheduling under a realistic A2G channel and regulatory kinematic constraints. Our bounded-action PPO–GAE agent coordinates UAV acceleration with per-subchannel power and adaptive SIC to maximize rate coverage. Across four canonical spatial layouts, it consistently outperforms PPO with OFDMA and placement/power baselines, raising the fraction of users above the minimum-rate threshold and reducing median UE transmit power (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 and Figure 13; Table 4 and Table 5). Ablations indicate that UL–NOMA with adaptive SIC, feasibility-aware actions, and joint trajectory–power decisions are all critical to the gains.

Limitations include the single-UAV/single-cell abstraction, simplified environment physics, and the use of a single primary objective. Future work will address multi-UAV settings, energy/flight-time constraints, weather and airspace restrictions, and multi-objective formulations. We plan to release seeds, configuration files, and environment scripts to facilitate reproducibility and benchmarking in this domain. Our current formulation omits an explicit propulsion/hover energy model for the UAV. Although endurance constraints can reshape feasible trajectories and scheduling, the present results focus on the coupling of motion and uplink resource allocation. Incorporating an energy-aware term in the reward and budgeted constraints is a promising extension we defer to future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.A., P.M.T. and M.D.; methodology, A.M.A. and P.M.T.; software, A.M.A.; validation, A.M.A., P.M.T., H.B.T., H.K., M.N.S. and M.D.; formal analysis, P.M.T., H.K. and M.D.; resources, P.M.T.; data curation, A.M.A. and P.M.T.; writing—original draft presentation, A.M.A. and P.M.T.; writing—reviewing and editing, A.M.A., P.M.T., H.B.T., H.K., R.A., A.K. and M.D.; supervision, P.M.T.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation under the Award OIA-2417062 to the DREAM Research Center and the UNM IoT and Intelligent Systems Innovation Lab (I2 Lab).

Data Availability Statement

The Python (v3.9.21) code and datasets used in this study including the simulated A2G environment with users, a fully functional UAV motion/kinematics module, UL–NOMA/SIC routines, and the bounded-action PPO–GAE training scripts—are available via the Distributed Resilient and Emergent Intelligence-based Additive Manufacturing (DREAM) project GitHub repository. Direct repository access is restricted; all data and code are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| 3GPP | 3rd-Generation Partnership Project |

| 5G | Fifth-Generation Mobile Network |

| A2G | Air to Ground |

| Adam | Adaptive Moment Estimation (optimizer) |

| CDF | Cumulative Distribution Function |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CSI | Channel-State Information |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| GAE | Generalized Advantage Estimation |

| LAP | Low-Altitude Platform |

| LoS | Line of Sight |

| MAC | Multiple Access Channel |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| NF | Noise Figure |

| NLoS | Non-Line of Sight |

| NOMA | Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| OMA | Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| OFDMA | Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access |

| pp | Percentage Point |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| SIC | Successive Interference Cancellation |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UAV-BS | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Base Station |

| UL | Uplink |

| UL–NOMA | Uplink Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| UMa | Urban Macro (3GPP) |

References

- Srivatsa, V.; Kusuma, S.M. Deep Q-Networks and 5G Technology for Flight Analysis and Trajectory Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 12–14 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Efficient trajectory optimization and resource allocation in UAV 5G networks using dueling-Deep-Q-Networks. Wirel. Netw. 2024, 30, 6687–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Kato, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Uplink/Downlink Resource Allocation in High Mobility 5G HetNet. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, S.; Qian, Y.; Hu, R.Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Dynamic Reputation Policy in 5G Based Vehicular Communication Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 6136–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, M.; Cervelló-Pastor, C.; Sallent, S. Deep Learning at the Mobile Edge: Opportunities for 5G Networks. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Wei, P.; Ying, L.; Liu, Y. Obstacle Avoidance for UAS in Continuous Action Space Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 90623–90634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciosek, K.; Whiteson, S. Expected Policy Gradients for Reinforcement Learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Caillouet, C.; Mitton, N. Optimization and Communication in UAV Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exposito Garcia, A.; Esteban, H.; Schupke, D. Hybrid Route Optimisation for Maximum Air to Ground Channel Quality. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 105, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, X.; Khan, T.; Afshang, M.; Mozaffari, M. 5G Air-to-Ground Network Design and Optimization: A Deep Learning Approach. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.08379. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Da, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ni, L.; Pan, Y. SE and EE Optimization for Cognitive UAV Network Based on Location Information. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 162115–162126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, P.; Gagnon, F.; Tran, L.N.; Labeau, F. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation in Cooperative UAV-Assisted Wireless Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 7610–7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubbati, O.S.; Lakas, A.; Guizani, M. Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning for Wireless-Powered UAV Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 16044–16059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, F.R. Intelligent Trajectory Design in UAV-Aided Communications with Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 8227–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, P.S.; Michailidis, E.T.; Nomikos, N.; Vouyioukas, D.; Kanatas, A.G. A Survey on Machine-Learning Techniques for UAV-Based Communications. Sensors 2019, 19, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning in NOMA-Aided UAV Networks for Cellular Offloading. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2022, 21, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jabbari, B.; Ansari, N. Deep Reinforcement Learning Driven UAV-Assisted Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 25449–25459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvirianti; Narottama, B.; Shin, S.Y. Layerwise Quantum Deep Reinforcement Learning for Joint Optimization of UAV Trajectory and Resource Allocation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Wu, F.; Wang, Y. Path Planning of UAV Based on Improved Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 89400–89411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Long, K.; Jiang, C.; Guizani, M. Joint Resource Allocation and Trajectory Optimization with QoS in UAV-Based NOMA Wireless Networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 20, 6343–6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, M.; Vidal-Calleja, T.; Hitz, G.; Chung, J.J.; Sa, I.; Siegwart, R.; Nieto, J. An informative path planning framework for UAV-based terrain monitoring. Auton. Robot. 2020, 44, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, Z.; Chen, D.; Liang, S.; Ma, H. Maneuvering target tracking of UAV based on MN-DDPG and transfer learning. Def. Technol. 2021, 17, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Fang, X.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.; Li, H.; Jin, H.; Song, Y. Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning for UAV Based on Improved RRT Algorithm. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 2022, 4544499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maboudi, M.; Homaei, M.; Song, S.; Malihi, S.; Saadatseresht, M.; Gerke, M. A Review on Viewpoints and Path Planning for UAV-Based 3-D Reconstruction. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 5026–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Cao, X.; Zheng, D.; Gao, Y.; Ng, D.W.K.; Renzo, M.D. Trajectory Design for UAV-Based Internet of Things Data Collection: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 3899–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.Y.; Denizer, S.N. Multi UAV Based Traffic Control in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kharagpur, India, 1–3 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakew, D.S.; Masood, A.; Cho, S. 3D UAV Placement and Trajectory Optimization in UAV Assisted Wireless Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R. Energy-Efficient UAV Communication with Trajectory Optimization. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2017, 16, 3747–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Su, Z.; Xu, Q. Game theoretical secure wireless communication for UAV-assisted vehicular Internet of Things. China Commun. 2021, 18, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matracia, M.; Kishk, M.A.; Alouini, M.S. On the Topological Aspects of UAV-Assisted Post-Disaster Wireless Communication Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhou, H.; Sun, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, N. Channel Assignment and Power Allocation Utilizing NOMA in Long-Distance UAV Wireless Communication. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 12970–12982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chang, Z.; Guo, X.; Hämäläinen, T. Energy Efficient Resource Allocation for Wireless Powered UAV Wireless Communication System with Short Packet. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2023, 7, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Lee, I. UAV-Aided Wireless Communication Designs with Propulsion Energy Limitations. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Dong, X.; Lu, T.; Xu, W.; Yuen, M. Distributed and Multilayer UAV Networks for Next-Generation Wireless Communication and Power Transfer: A Feasibility Study. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 7103–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guizani, M. Secure UAV Communication Networks over 5G. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Kumar, H.; Davari, A. Performance evaluation of OFDM transmission in UAV wireless communication. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Southeastern Symposium on System Theory, Tuskegee, AL, USA, 20–22 March 2005; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H. Resource Allocation for 5G-UAV-Based Emergency Wireless Communications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2021, 39, 3395–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Che, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, K. Throughput Maximization for Laser-Powered UAV Wireless Communication Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), Kansas City, MO, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R. Energy Minimization for Wireless Communication with Rotary-Wing UAV. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 2329–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnagar, S.I.; Salhab, A.M.; Zummo, S.A. Q-Learning-Based Power Allocation for Secure Wireless Communication in UAV-Aided Relay Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 33169–33180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, Q.; Mao, K.; Ali, F.; Chen, X.; Zhong, W. Generative Network-Based Channel Modeling and Generation for Air-to-Ground Communication Scenarios. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Ndreveloarisoa, A.F.; Desheng, W.; Heriniaina, R.F.; Murad, N.M.; Fontgalland, G.; Ravelo, B. Channel Modelling for UAV Air-to-Ground Communication. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical, Electronic and Communications Engineering (ELECOM), Balaclava, Mauritius, 20–22 November 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, B.; Li, T.; Mao, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Zhong, W.; Zhu, Q. A UAV-aided channel sounder for air-to-ground channel measurements. Phys. Commun. 2021, 47, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hourani, A.; Kandeepan, S.; Lardner, S. Optimal LAP Altitude for Maximum Coverage. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2014, 3, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X. Deploying UAV Base Stations in Communication Networks Using Machine Learning. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, R.W.; McLain, T.W. Small Unmanned Aircraft: Theory and Practice; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Demographics of the World. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_the_world (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration. Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Regulations (Part 107). 2025. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/small-unmanned-aircraft-systems-uas-regulations-part-107 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Yu, L.; Li, Z.; Ansari, N.; Sun, X. Hybrid Transformer Based Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Multiple Unpiloted Aerial Vehicle Coordination in Air Corridors. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2025, 24, 5482–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.