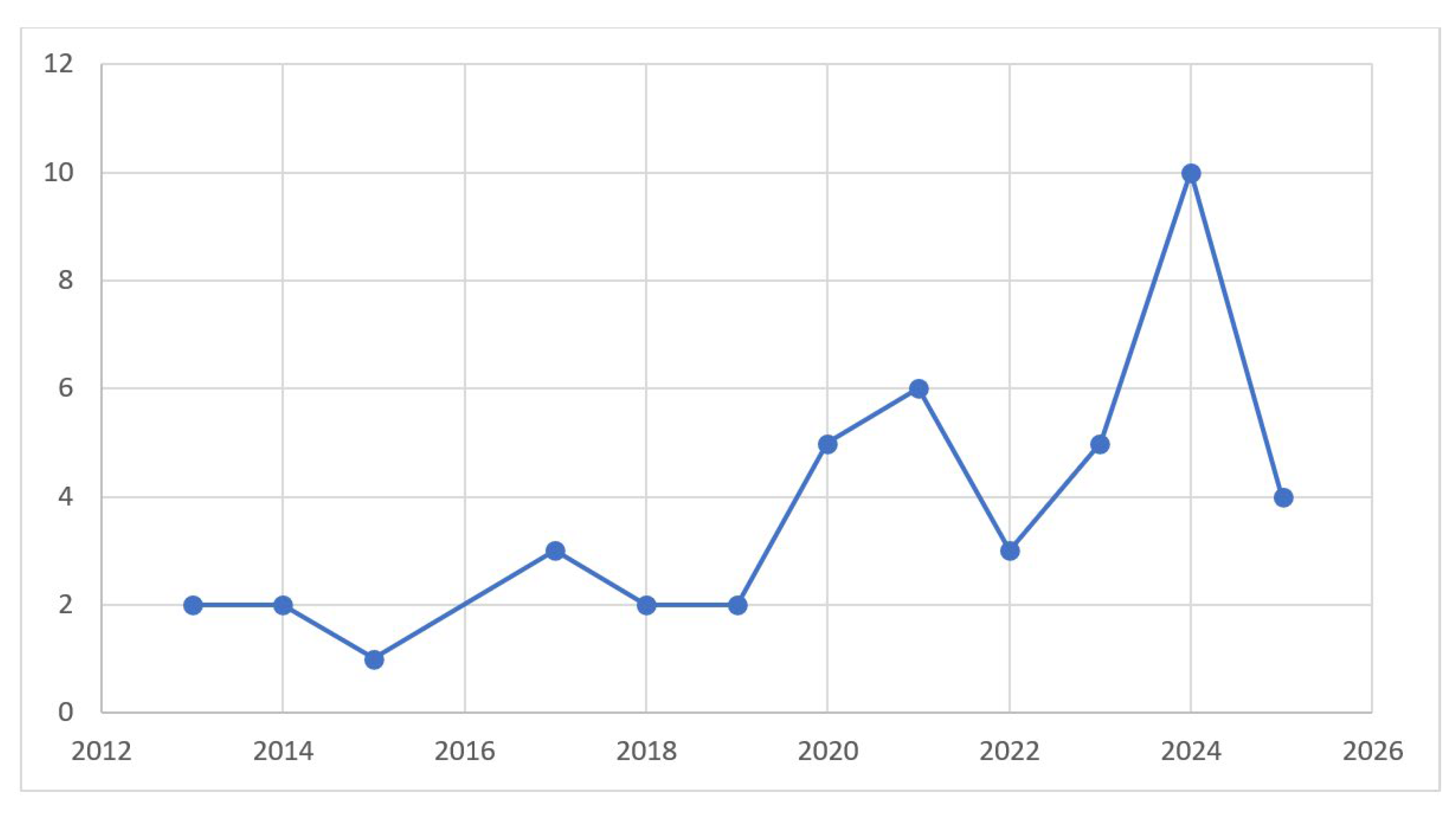

1. Introduction

Rapid advances in construction robotics have intensified the interest in human–robot collaboration (HRC) as a means of addressing persistent challenges in infrastructure delivery, including unsafe working conditions, labour shortages, low productivity growth, and operational inefficiencies. By combining the physical capabilities of robots, such as precision, endurance, and hazard tolerance, with human cognition, adaptability, and decision-making, HRC has the potential to fundamentally reshape how construction work is planned and executed in order to build infrastructure better [

1,

2]. Though their potential is undeniable, having robots on the job site alongside human workers complicates their roles, responsibilities, and safety, hence the concerns from built environment stakeholders on how to enhance human–robot teaming (HRT) without its associated impediments. Prevalent trends in the construction industry show that the use of robotic systems and the growing emphasis on integrating these technologies into different phases of the construction process are seeing a noticeable rising trajectory [

2,

3].

In response to the aforementioned issue, the construction sector has witnessed significant advancements in diverse robotic technologies. These technologies are specifically utilised for tasks involving repetition and physical exertion, potentially enhancing workers’ productivity [

4]. As highlighted in

Figure 1, such robotic systems include robotic bricklaying systems, flying robots such as drones for progress monitoring, inventory monitoring, health and safety assessment, transport logistics, etc. [

4,

5]. Other robotic systems include autonomous ground vehicles in construction, applicable to earthmoving autonomous vehicles, exoskeletons, cranes, trucks, 3D printing robots, etc. [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Robotic applications in prefabrication include those involved in latitudinal anchor installation, concrete element preparation, and cleaning and mapping [

5,

6]. Others also include shuttering robots called formwork robots, which are utilised in effective and precise shuttering on prefabricated elements, robotic production systems for reinforcement, robots for cutting and inserting insulation, robotic concrete spreaders, and cladding robots [

7]. The application of human–robot collaboration (HRC), which leverages the combined skills of humans and robots, has the potential to digitally transform the construction industry. This transformation is expected to resolve current industry issues with regard to the lack of productivity gains, hazardous work conditions, labour shortages, and failing infrastructure [

11].

Beyond productivity and efficiency considerations, the deployment of robots in construction is increasingly motivated by their ability to operate effectively in environments that are hazardous, physically demanding, or unsuitable for sustained human presence [

8,

9,

10]. Construction sites are frequently characterised by dust-intensive conditions, including cement handling, concrete cutting, demolition, tunnelling, mining-adjacent works, and earthmoving operations [

11,

12]. A prolonged exposure to airborne particulate matter in such environments poses significant health risks to workers, including respiratory diseases and long-term occupational illness [

13,

14]. Robots, by contrast, can function reliably in dusty environments with appropriate sensor protection and enclosure design, thereby reducing direct human exposure while maintaining operational continuity.

In addition to dust-laden conditions, construction activities often involve dynamic and high-impact loading scenarios, such as lifting, repetitive material handling, vibration-intensive tasks, and interactions with heavy equipment [

11,

15,

16]. These dynamic loads introduce fatigue, musculoskeletal disorders, and accident risks for human workers, particularly during repetitive or precision-critical operations. Robotic systems and human–robot teams are well suited to such contexts, as robots can absorb, stabilise, or repeatedly execute load-bearing and vibration-prone tasks with a consistent accuracy, while human operators retain supervisory, decision-making, and adaptive roles [

4,

17,

18].

Consequently, the relevance of human–robot collaboration extends beyond conventional building projects to industries and locations where extreme operating conditions prevail, including large-scale infrastructure projects, underground construction, mining-related construction works, industrialised prefabrication facilities, and post-disaster or unsafe environments [

19,

20]. In these contexts, the effective collaboration between humans and robots is not merely an efficiency enhancement but a critical enabler of safe, resilient, and sustainable construction delivery [

21]. However, operating in high-risk environments and under dynamic loads also amplifies technical, safety, organisational, and behavioural challenges, reinforcing the need to systematically identify and address the barriers that hinder effective human–robot collaboration in construction [

22,

23].

Regardless of the growing body of literature on construction robotics and human–robot collaboration, the existing studies remain largely fragmented in scope and focus [

24,

25,

26]. Prior research has predominantly examined isolated aspects of human–robot collaboration, such as technological feasibility, safety risks, worker perception, or adoption barriers, often treating these factors as independent challenges rather than as an interconnected system [

27,

28]. Moreover, while several studies have identified lists of barriers to robot adoption in construction, there is limited effort to structurally analyse the interdependencies among these barriers or to prioritise them based on their driving and dependence relationships [

29,

30]. As a result, decision-makers are left without a clear understanding of which barriers act as root constraints and which are consequential outcomes within the broader human–robot collaboration ecosystem [

31,

32].

To address this gap, this study advances the existing knowledge by providing a systematic, theory-driven synthesis of barriers to human–robot collaboration, followed by the development of an integrated interpretive structural model (ISM) that explicitly maps the hierarchical and causal relationships among these barriers. By combining a PRISMA-based systematic review with expert-validated ISM and MICMAC analyses, the study moves beyond descriptive barrier identification and offers a systems-level explanation of how regulatory, organisational, technological, social, and safety-related factors interact to shape collaboration outcomes. This integrated perspective constitutes the study’s primary contribution, enabling a more informed prioritisation of interventions and laying a structured foundation for future empirical validation in real construction contexts.

Accordingly, this study aims to advance the understanding of human–robot collaboration in construction by systematically identifying barriers reported in the literature and structuring their interrelationships using a systems-based ISM approach. Specifically, the study pursues three objectives: (i) to identify and synthesise barriers to collaboration in construction human–robot teams through a PRISMA-based systematic review; (ii) to model the causal relationships and hierarchical structure of these barriers using interpretive structural modelling and MICMAC analysis; and (iii) to derive integrated, literature-grounded strategies that can inform policy, organisational decision-making, and future empirical validation. The study is introduced in

Section 1,

Section 2 provides a theoretical framework for the investigation. The study’s method is discussed in

Section 3. The results are presented in

Section 4, and the findings in relation to the objectives and existing studies are discussed in

Section 5. The study’s conclusions and limitations are presented in the

Section 6.

2. Theoretical Framework

The integration of human–robot collaboration (HRC) in construction is also a behavioural and organisational decision-making process shaped by perceptions of risk, capability, responsibility, and control within complex project environments. As such, behavioural theories of technology adoption provide an appropriate foundation for examining why collaborative robotic systems are embraced, resisted, or selectively implemented in practice [

33,

34].

Early technology adoption research has been dominated by models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which emphasises perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as predictors of adoption intention [

14,

35]. While TAM has demonstrated value in explaining the uptake of information systems in construction, its applicability to construction robotics is limited. Collaborative robots are not passive tools; they actively interact with human workers, operate in dynamic environments, and introduce safety, liability, and organisational implications that extend beyond individual perceptions of utility or usability. As noted by Kim et al. [

9], the complexity and socio-technical nature of robot–human interactions challenge the explanatory power of TAM in construction contexts.

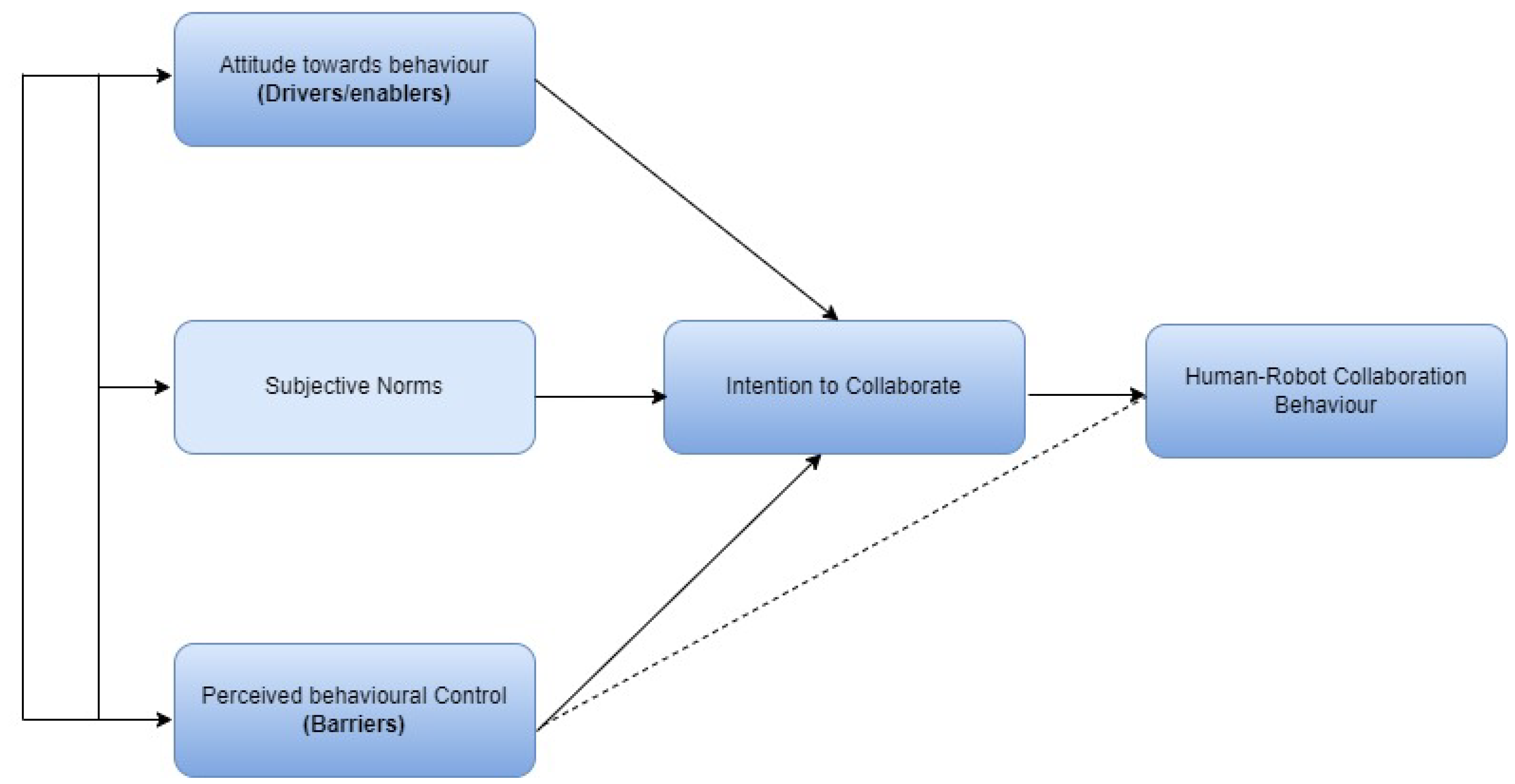

To address these limitations, this study adopts the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as its primary theoretical anchor. TPB is particularly suited to construction HRC because it conceptualises behaviour as intentional and constrained, shaped not only by attitudes but also by perceived control and contextual limitations [

36]. In construction settings, decisions to deploy collaborative robots are rarely individual choices; they are negotiated outcomes influenced by organisational strategy, regulatory frameworks, safety requirements, workforce capability, and project-specific constraints.

Figure 2 presents the theoretical framework underpinning this study, adapted from TPB to reflect the realities of human–robot collaboration in construction. In studies based on TPB, attitudes towards behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control jointly influence behavioural intention [

37]. In complex socio-technical systems such as construction, however, these constructs manifest at both individual and organisational levels. Consequently, this study extends TPB by interpreting attitudes towards behaviour as the strategic orientation and enabling actions adopted by organisations and decision-makers to facilitate human–robot collaboration, rather than as purely individual sentiments [

33,

34]. HRC in construction is a socio-technical issue requiring an understanding of its social and technical dynamics [

38,

39].

Similarly, perceived behavioural control is conceptualised in this study as a representation of structural and systemic barriers that constrain the ability of individuals and organisations to engage in effective human–robot collaboration [

38]. Within construction contexts, behavioural control is rarely determined solely by personal capability; instead, it is shaped by regulatory constraints, safety requirements, technological limitations, skill gaps, and organisational readiness [

36,

40]. Framing perceived behavioural control as a barrier therefore reflects the practical conditions under which collaboration decisions are made, aligning TPB with the operational realities of construction projects.

This theoretical reinterpretation provides a coherent bridge between TPB and the interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach adopted in this study. By distinguishing drivers and enablers (attitude-based strategies) from constraints and barriers (perceived control limitations), the framework enables a structured examination of how intention to collaborate emerges from the interaction between enabling strategies and limiting conditions [

35,

41,

42,

43]. This distinction also supports the subsequent identification, structuring, and prioritisation of barriers and strategies through ISM and MICMAC analyses, thereby ensuring theoretical consistency across the study.

Accordingly, this study conceptualises attitude towards behaviour as the strategic and enabling actions adopted by decision-makers to promote effective human–robot collaboration, while perceived behavioural control is interpreted as the structural and systemic barrier that limits collaborative intent and implementation. This integrated theoretical perspective underpins the systems-based analysis developed in the remainder of the paper.

3. Research Method

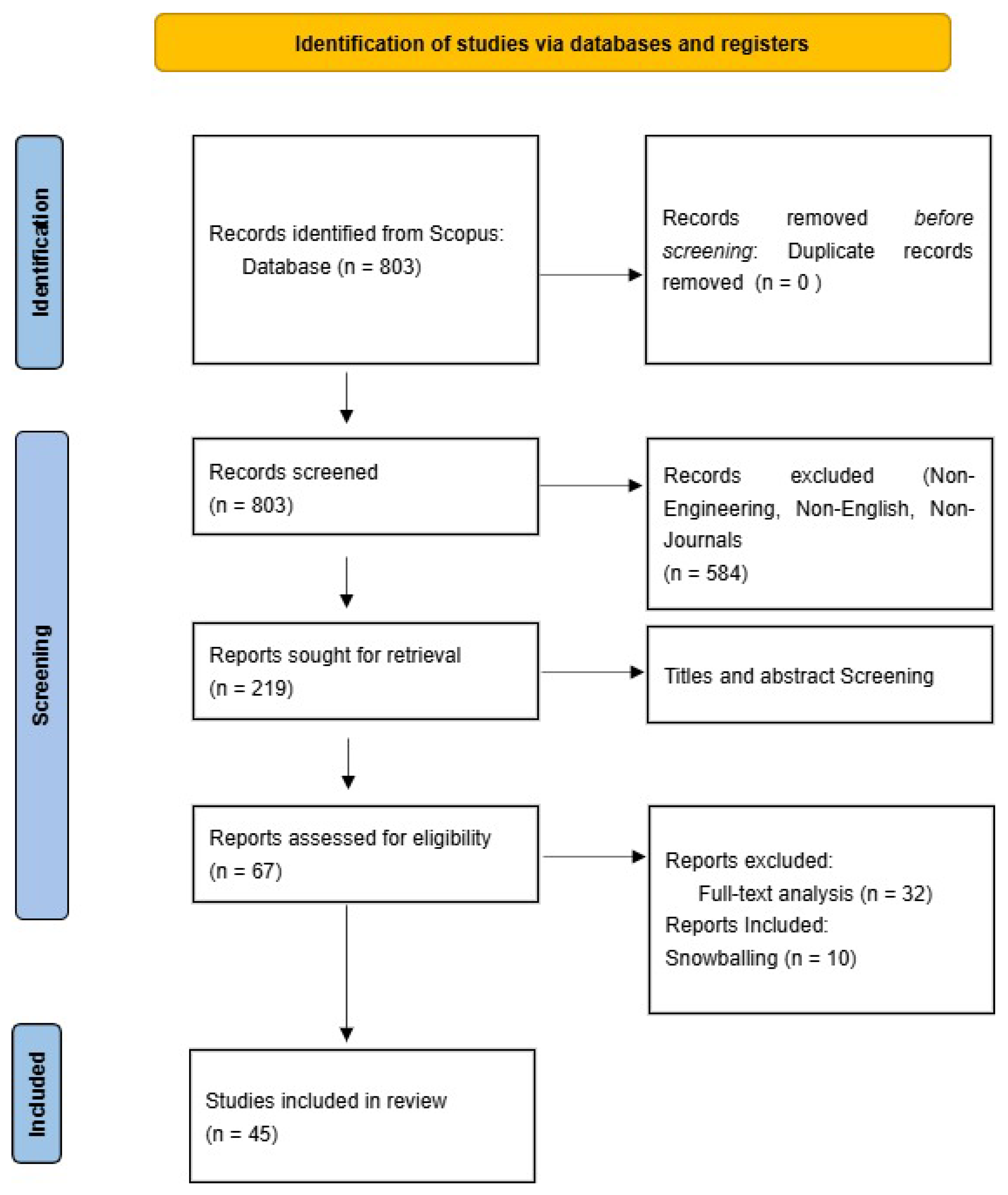

This study adopts a literature-driven interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach to examine the barriers to effective human–robot collaboration in the construction industry [

15,

17]. The method is widely used in sustainable development [

44], manufacturing [

44], and construction [

37]. The methodological design is intentionally aligned with the study’s objective of developing a theory-building, system-level understanding of how multiple barriers interact and shape collaborative outcomes, rather than empirically testing adoption levels or behavioural intentions in specific project contexts, as depicted in

Figure 3. This study used the PRISMA method, which is evidence-based, to identify and highlight the barriers to collaboration in human–robot teams. The systematic literature review (SLR) is an essential technique for evaluating the progress and current level of research in an area [

45]. This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. In line with the objective of developing a theory-building and system-level understanding of barriers to human–robot collaboration, this study did not involve primary data collection through surveys or case studies. Instead, it adopted a literature-driven interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach, where the systematic literature review served as the principal data source [

44]. This methodological choice aligns with prior ISM-based studies that rely on validated secondary evidence to model complex relationships among constructs, particularly where empirical adoption remains emergent and fragmented [

46,

47,

48]; the PRISMA framework is described in

Figure 3 below.

3.1. Search Strategies and Sampling

To locate the relevant papers, a comprehensive search was conducted in the Scopus database. Scopus sets itself apart from Web of Science and other databases with its broad coverage, accuracy, and easy-to-use article retrieval features [

17,

18]. To guarantee that any articles with the specified keywords within their corresponding title, abstract, or keywords sections would be retrieved, the search parameters in Scopus were set to “title/abstract/keywords”. Xiao et al. [

48] indicate that robot and robotics are two relatively simple keywords that can be used to choose keywords linked to the robotics theme. Nevertheless, choosing appropriate keywords associated with the construction theme is a complex task. When employing the single term “construction”, the search results will yield many publications that are not directly relevant to the construction sector. In order to determine the article’s applicability to the construction industry, the writers employed an approach that included the previously mentioned keywords. By consulting the existing literature review studies conducted in the field of construction research, such as those by Xiao et al. [

48] and Chen et al. [

19], keywords relevant to the construction subject were identified. During the search, the plural form of a few words was included using a wildcard (*). Following the first search, the snowballing strategy was used to guarantee that all pertinent articles were included, both forward and backwards.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The process of selecting literature for benchmarking purposes involved the application of certain criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Following the initial keyword search, more refinement was undertaken. Publications from fields like the arts, science, nursing, agriculture, and biology were omitted because they had no bearing on the subject of the study. Additionally, the publications were only to include papers written in English. Another inclusion yardstick was that studies should have a strong connection with human–robot teams and collaboration in robotics; the studies considered barriers to collaborating with robots in human–robot teams. Finally, the exclusion yardstick includes papers from unrelated journals or conference proceedings carefully scrutinised by their source titles. There was no particular constraint on the selection of literature based on article type, publication year, or country to ensure that pertinent studies were not left out. The search keywords are presented below: (“barrier*” OR “critical barrier*” OR “challenge*” OR “problem*” OR “factor*” OR “constraint*”) AND (“construction engineering” OR “construction management” OR “construction project” OR “construction automation” OR “building engineering” OR “building project” OR “modular construction” OR “modular building” OR “offsite construction” OR “off-site construction” OR “industrialized construction” OR “prefabricated construction” OR “precast construction”) AND (“robot*” OR “robotic*” OR “cobot*” OR “human-robot*” OR “human-robot team*” OR “collaborative robot*”).

3.3. Articles Content Review

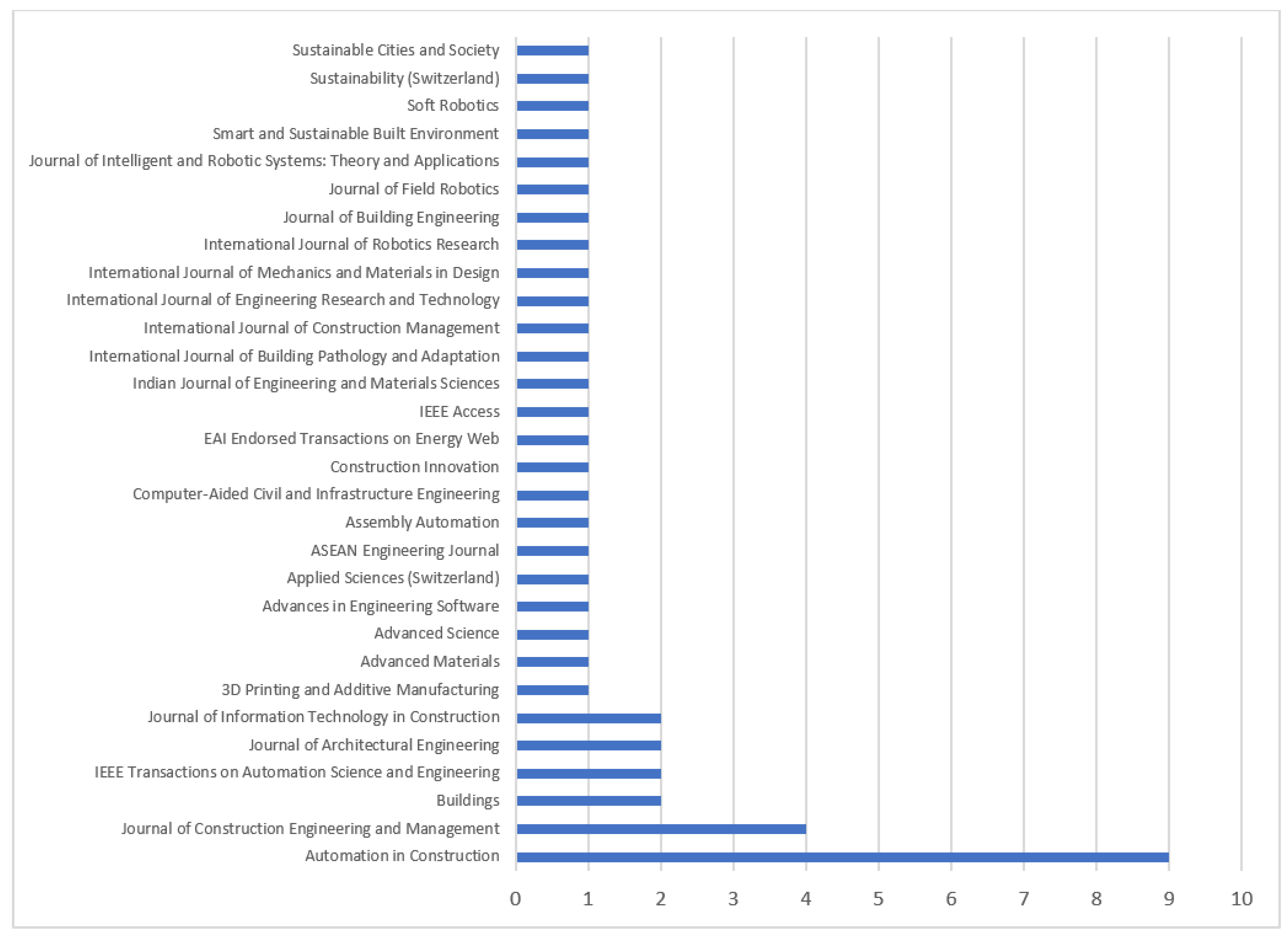

The search review from the Scopus database produced 803 results relevant to the search criteria. Careful attention was given to screening the 803 results for their title and abstract aligning with the study’s objectives. A total of 67 papers emanated from this screening, which was narrowed down to 35 papers after full-text reading. Backward and forward snowballing produced 10 more articles, bringing the total number of articles to 45. The analysis of records retrieved from the Scopus database was conducted using Scopus’s built-in analytical and export tools, which enable the structured filtering, screening, and bibliographic assessment of large datasets. Following the initial search, Scopus’s document analysis functions were used to refine results based on document type, subject area, and language, thereby supporting the preliminary exclusion of non-relevant studies. Title and abstract screening were performed manually using exported metadata (including titles, abstracts, keywords) to ensure an alignment with the study objectives.

To support consistency and transparency during screening, the bibliographic data were exported from Scopus in spreadsheet-compatible formats, allowing the systematic comparison, categorisation, and tracking of inclusion and exclusion decisions. This process facilitated an iterative refinement of the dataset and enabled the integration of forward and backward snowballing, ensuring that influential studies not fully captured through keyword-based retrieval were also considered in the final review set. While the PRISMA framework provides a transparent and replicable structure for identifying, screening, and selecting relevant literature, its application is not without limitations [

49,

50]. In particular, the screening stage is inherently dependent on the clarity and consistency of titles, abstracts, and author-assigned keywords, which may not always fully capture the depth or relevance of studies addressing human–robot collaboration in construction. As a result, potentially relevant studies may be inadvertently excluded during early screening stages, especially where interdisciplinary research is reported using non-standard terminology [

51].

To mitigate this limitation, this study complemented the PRISMA-based screening process with snowballing, ensuring that influential and contextually relevant studies not captured through database screening alone were incorporated. This combined approach strengthens the robustness of the review while recognising the methodological boundaries associated with PRISMA-driven screening procedures.

3.4. Expert Input for ISM Development

To support the development of the ISM framework, expert judgement was employed solely to validate the directional relationships among the identified barriers, rather than to generate new empirical data [

52,

53]. A purposive panel of five academic experts was engaged based on the following selection criteria: (i) a minimum of ten years of research experience in construction automation, robotics, or digital construction; (ii) prior publication record in construction robotics or human–robot interaction; and (iii) familiarity with ISM or related systems-thinking methodologies [

54,

55]. The ISM development followed an iterative consensus-based process, where experts independently reviewed the contextual relationships between barrier pairs based on evidence synthesised from the literature [

56]. Discrepancies in judgement were resolved through structured discussion and refinement until consensus was achieved. This approach is consistent with established ISM practices, where expert agreement is prioritised over statistical inter-rater reliability, given the interpretive and relational nature of the method [

52,

57]. As the expert input was used for structural validation rather than measurement or scoring, formal inter-rater reliability metrics were not applied. Instead, methodological rigour was ensured through the transparency of the literature synthesis, iterative validation, and consistency checks embedded within the ISM and transitivity procedures. The

Supporting Information for the study can be found in the

Supplementary Materials section.

5. Discussion of Findings

This section interprets the findings of the ISM–MICMAC analysis to explain how barriers to human–robot collaboration interact as a system rather than as isolated constraints. Unlike prior studies that primarily catalogue challenges to construction robotics adoption, this study advances understanding by revealing the hierarchical structure and directional dependencies among barriers, thereby clarifying where intervention efforts are most likely to yield systemic impact.

5.1. Interpretive Structural Modelling Results on Barriers to Collaboration in Human–Robot Teams

This study employed a blend of expert interviews and systems thinking methodologies to formulate a detailed conceptual framework that illustrates the interrelationships among various barriers. This approach was undertaken to justify the developed structure. To represent these connections between barriers (i and j) in

Table 1, the authors used specific symbols (V, A, X, O). Subsequently, the ISM matrix was converted into a reachability matrix by replacing these symbols with binary values (1 and 0) based on the defined criteria.

The determination of the contextual relationships (V, A, X, O) between pairs of barriers was guided by evidence synthesised from the systematic literature review, complemented by structured expert judgement [

58]. For each pair of barriers, experts examined whether empirical and conceptual evidence in the reviewed studies suggested a directional influence, mutual influence, or no discernible relationship [

44]. Where multiple studies consistently indicated precedence or causality (e.g., regulatory frameworks influencing organisational readiness), directional relationships (V or A) were assigned. Mutual reinforcement supported an X relationship, while the absence of evidence for interaction resulted in an O designation [

59]. This evidence-informed process ensured that the ISM matrix was grounded in the literature rather than subjective intuition. To achieve consensus, experts initially assessed the barrier relationships independently. The determination of relationships in the ISM matrix followed a structured consensus-based judgement process, rather than a statistical voting procedure. Each expert independently assessed the direction and nature of influence between barrier pairs based on evidence synthesised from the systematic literature review. The initial assessments were then compared across experts to identify areas of convergence and divergence.

Where full agreement was observed, the corresponding relationship (V, A, X, or O) was directly assigned. In cases where discrepancies emerged, the relationship was resolved through iterative discussion and justification, during which experts referenced supporting or contradictory findings from the reviewed studies. Consensus was defined as agreement by the clear majority of experts, supported by dominant evidence in the literature, rather than by numerical voting thresholds. This process ensured that the final ISM matrix reflects prevailing and defensible relational patterns, rather than isolated subjective opinions.

As ISM is an interpretive and theory-building method, the emphasis was placed on relational coherence and explanatory validity rather than on the inter-rater reliability statistics typically associated with survey-based measurement. This consensus-oriented approach is consistent with established ISM applications in complex socio-technical systems, where expert reasoning is used to structure relationships rather than to generate probabilistic estimates. Divergent assessments were subsequently reviewed through iterative comparison and structured discussion, during which experts justified their positions by referring back to documented findings in the literature [

59]. Consensus was considered achieved when agreement was reached on the dominant direction or nature of influence supported by the strongest body of evidence. This iterative consensus-based approach is consistent with established ISM practice, where relational clarity is prioritised over statistical agreement measures. The guidelines for transforming into a reachability matrix are as follows:

If the cell (i, j) is V, then cell (i, j) entry is 1 and cell (j, i) entry is 0.

If the cell (i, j) is A, then cell (i, j) entry is 0 and cell (j, i) entry is 1.

If the cell (i, j) is X, then cell (i, j) entry is 1 and cell (j, i) entry is 1.

If the cell (i, j) is O, then cell (i, j) entry is 0 and cell (j, i) entry is 0.

5.1.1. Final Reachability Matrix

To create the final reachability matrix, the initial reachability matrix given in

Table 2 was put through a transitivity procedure. A loop statement is used by the transitivity methodology to methodically examine each barrier. The linkage between barriers A, B, and C depends on the relationship between A and B, followed by the connection between B and C, thereby forming a clear and direct association between A and C. The majority of studies on ISM have predominantly employed a manual technique, which has been found to be both time-consuming and susceptible to errors. Therefore, the transitivity was evaluated using a Python code (Python 3.14.2) as described in the work of Saka and Chan [

54]. Including this aspect was of utmost importance to improve the precision of the findings, and its validity has been corroborated by previous studies [

60,

61]. Although a formal sensitivity analysis was not conducted, framework robustness was assessed through transitivity checks, expert validation, and MICMAC classification consistency [

43,

47]. The use of computational transitivity ensured a logical coherence in the reachability matrix, while the stability of the barrier positions across ISM levels and MICMAC quadrants served as an internal validation of the structural relationships [

46]. This triangulated validation approach is commonly adopted in interpretive structural modelling studies where the objective is theory development rather than predictive testing. The final reachability matrix is shown in

Table 3.

def transitivity (matrix):

result = " "

length = len (matrix)

for i in range (0, length):

for row in range (0, length):

for col in range (0, length):

matrix [row] [col] = matrix [row] [col] or (matrix[row] [i] and matrix [i] [col])

result += ("\n W" + str (i) +" is:\n"+ str(matrix).replace ("],","]\n") + "\n")

result += ("\n Final Reachability Matrix is\n" + str(matrix).replace(" ], " , " ] \n"))

print (result)

return result

transitivity(B)

While the ISM analysis provides a structured representation of the relationships among barriers, it is important to acknowledge that not all barrier interactions exhibit uniform strength or certainty across the literature. In some cases, discrepancies emerged regarding the direction or magnitude of influence between barriers, reflecting differences in construction contexts, project types, and levels of technological maturity reported in prior studies. For example, certain studies emphasise safety as a primary driver of adoption, whereas others position it as a dependent outcome shaped by organisational readiness and regulatory frameworks.

To address these uncertainties, the ISM relationships were determined based on dominant and recurring patterns observed across the reviewed literature and validated through expert consensus. Where evidence suggested bidirectional or context-dependent influence, mutual relationships (X) were assigned. This approach ensures that the model reflects prevailing tendencies rather than absolute causal claims, consistent with the interpretive nature of ISM.

5.1.2. Reachability Matrix Partitioning into Different Levels

The final reachability matrix was employed to calculate the reachability set, antecedent set, and intersection set for each barrier in order to ascertain their partition levels [

44,

62]; The obstacles inside the reachability sets encompass not only the barrier itself but also the impediments that facilitate its attainment [

58]. The antecedent sets encompass both the barrier itself and the auxiliary barriers that facilitate its attainment [

56]. The intersection of the variable sets for all variables was achieved. The barriers with the same level of reachability and intersection set were divided into specific categories. After identifying the primary obstacles, they were distinguished from the other impediments. The barriers were categorised into three levels: Level I, encompassing financial factors, robot technology-related factors, social and human factors, and organisational factors; Level II, including safety factors and education/training factors; and Level III, consisting of communication factors and legal/regulatory factors. The result is displayed in

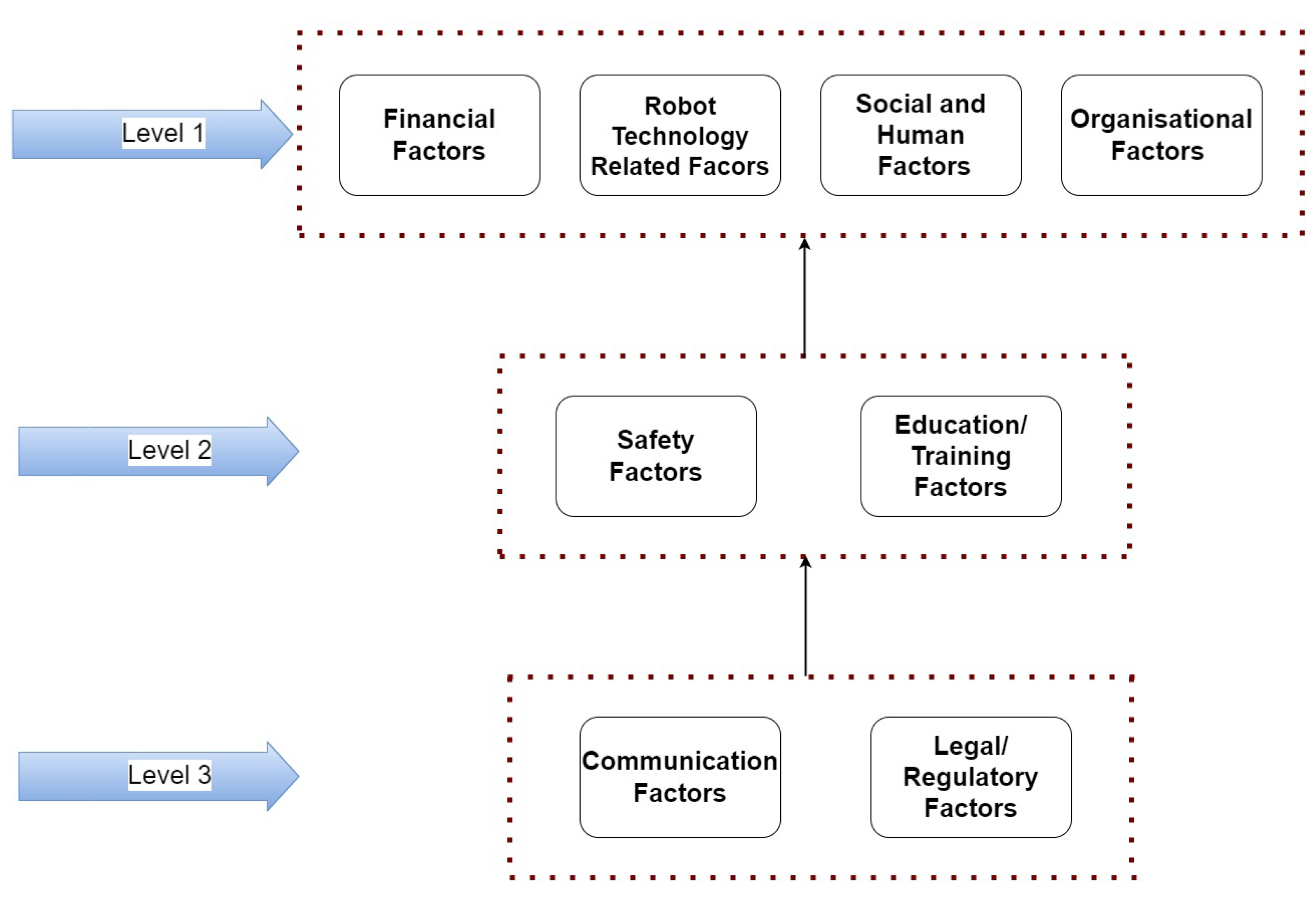

Table 4.

Table 4 and

Table 5 display the iterations. Based on their respective levels, the barriers’ locations within the conceptual framework were chosen. The hierarchical structuring of barriers into Levels I, II, and III reveals a clear progression of influence within the system. Level III barriers (communication and regulatory factors) function as foundational drivers that shape organisational readiness, safety practices, and training structures at Level II. These, in turn, influence Level I outcome barriers, including financial, technological, and social factors. This cascading relationship underscores the importance of addressing higher-level drivers before attempting to resolve dependent constraints, thereby reinforcing the logic of the proposed ISM hierarchy.

5.2. MICMAC Analysis of Barriers to Collaboration in HRTs

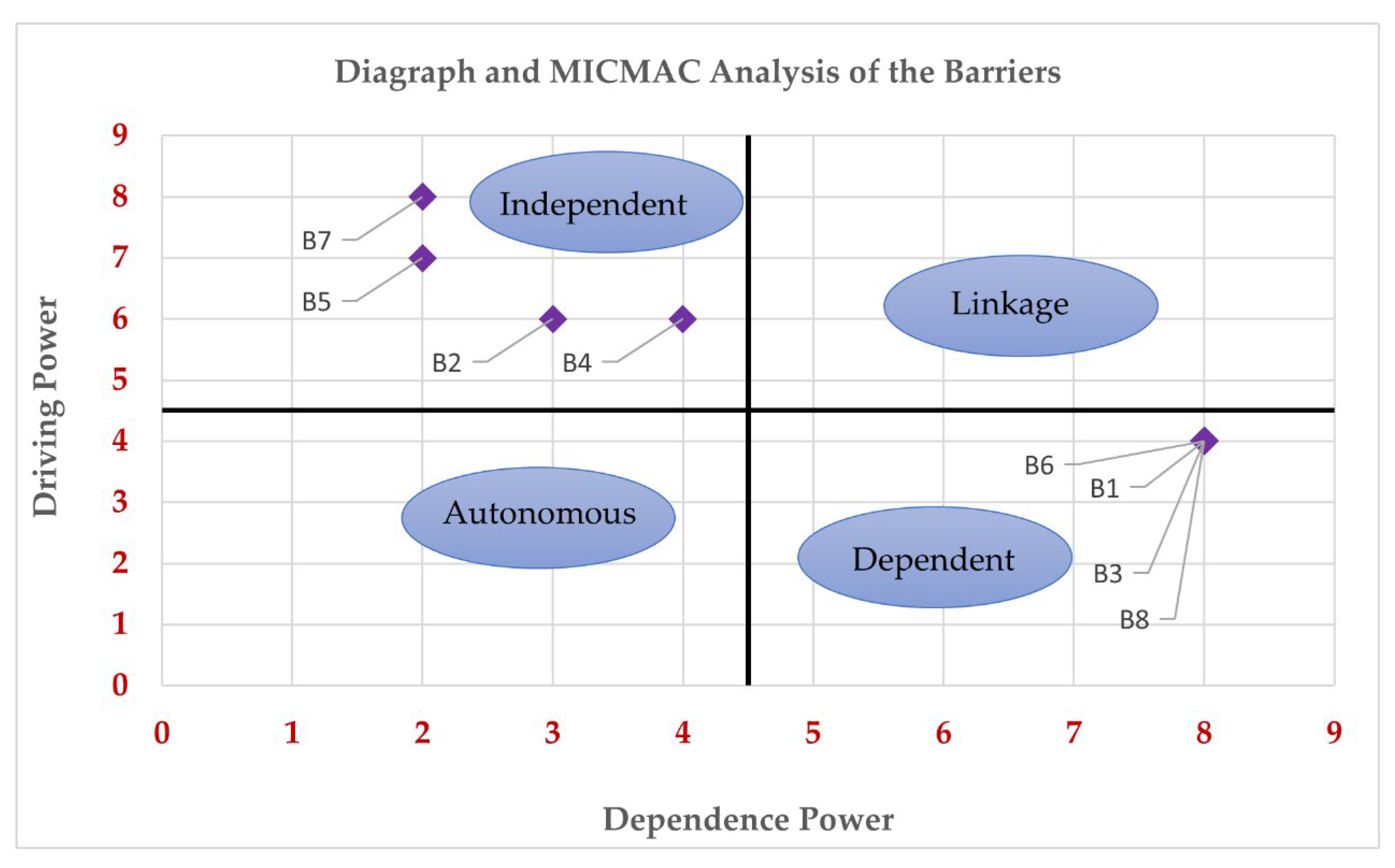

Driving power reflects the extent to which a barrier influences other barriers within the system, while dependence power indicates the degree to which a barrier is influenced by others. Barriers with a high driving power act as root or triggering constraints, whereas those with a high dependence power tend to be outcome-oriented or symptomatic. Interpreting barriers through this lens enables the prioritisation of interventions, as addressing high-driving barriers can generate cascading system-wide improvements. As shown in

Figure 6, the MICMAC technique was employed to categorise the barriers into four distinct categories [

43,

47]. The four distinct categories includes autonomous, dependent, linkage, and independent groupings [

46,

57]. In the independent group are safety, education/training, communication, and legal/regulatory factors. Belonging to the independent group indicates that these barriers have a strong driving power but a minimal dependence on other factors. In the dependent group are the financial factors, robot technology-related factors, social and human factors, and organisational factors. This indicates that they exhibit a low driving power but a high level of dependence [

54,

56]. The unoccupied quadrants are the linkage and autonomous quadrants. The absence of barriers within the autonomous and linkage quadrants indicates a highly interconnected barrier structure in the context of human–robot collaboration in construction [

46]. Autonomous barriers, which exhibit a weak driving and weak dependence power, typically represent isolated issues; their absence suggests that all identified barriers are systemically relevant. Similarly, the lack of linkage barriers, characterised by strong driving and strong dependence, implies that feedback-dominant instability is limited within the system [

46]. This structural pattern reflects the maturity and coherence of the identified barriers, where each constraint either functions as a driver or as a dependent outcome, reinforcing the suitability of a systems-based intervention approach. Therefore, all the barriers examined in this study are crucial and have a significant impact on HRC.

The positioning of communication factors and legal/regulatory factors at the highest level of the ISM hierarchy and within the independent (high-driving) quadrant of the MICMAC analysis underscores their systemic influence on human–robot collaboration in construction. Unlike downstream barriers that manifest as operational or outcome-based challenges, deficiencies in regulatory clarity and communication infrastructures act as foundational constraints, shaping organisational readiness, safety governance, training effectiveness, and technology integration.

In particular, inadequate legal and regulatory frameworks introduce an uncertainty regarding liability, accountability, compliance, and permissible modes of human–robot interaction, which in turn discourages investment, limits organisational commitment, and constrains safety planning. Similarly, weak communication mechanisms, both human–human and human–robot, undermine coordination, trust, situational awareness, and task allocation on site. The ISM results therefore suggest that interventions targeting these high-level barriers are likely to generate cascading improvements across multiple dependent barrier categories, reinforcing the need for systems-oriented rather than isolated implementation strategies. The classification of barriers into eight categories, financial, safety, communication, robot technology-related, organisational, legal/regulatory, education/training, and social and human factors, was guided by a combination of recurring thematic patterns identified in the systematic literature review and an alignment with established classification approaches in construction robotics, technology adoption, and socio-technical systems research.

Figure 6. Shows the Digraph and MICMAC analysis of barriers to collaboration in construction human–robot teams. B1–B8 represent the barrier categories analysed in this study: B1—Robot technology-related factors; B2—Safety factors; B3—Financial factors; B4—Education and training factors; B5—Communication factors; B6—Social and human factors; B7—Regulatory and legal factors; and B8—Organisational factors. Prior studies commonly distinguish between technical, organisational, human, and regulatory dimensions when examining construction innovation adoption; this study extends these perspectives by further disaggregating communication and education/training as distinct categories due to their recurrent and cross-cutting influence across the reviewed studies. This classification enhances analytical clarity while remaining consistent with the existing barrier taxonomies reported in the construction and human–robot interaction literature.

Comparative Interpretation and Theoretical Implications of the ISM–MICMAC

The existing research on construction robotics and human–robot collaboration has consistently identified barriers related to safety, skills gaps, cost, technological reliability, organisational readiness, and regulatory uncertainty [

63,

64]. However, much of this work has tended to present barriers as parallel lists or as domain-specific challenges (e.g., technical versus human factors) without clarifying how these constraints interact, accumulate, or cascade across the adoption pathway [

65,

66]. The present study complements these contributions by demonstrating that barriers to collaboration in construction human–robot teams exhibit a structured hierarchy and interdependence, meaning that some constraints function primarily as upstream drivers while others manifest as downstream outcomes of the wider system configuration.

A key contribution of this study lies in the identification of communication factors and legal/regulatory factors as Level III drivers. Prior studies frequently discuss these themes as important enablers of safe robotic deployment, yet they are often treated as “supporting issues” rather than foundational constraints [

67,

68]. The ISM hierarchy indicates that regulatory clarity and communication infrastructures shape the conditions under which organisations design roles, responsibilities, training provisions, and safe work procedures. This implies that deficiencies in regulatory guidance and collaboration communication interfaces may propagate into weak safety practices and inadequate training architectures, which subsequently influence financial feasibility, technology integration performance, and social acceptance outcomes [

69].

The MICMAC results further reinforce this interpretation by distinguishing between barriers with a high driving power (independent group) and those with a high dependence power (dependent group). Specifically, safety and education/training emerge as strong drivers, indicating that capability development and risk governance are not merely operational concerns but core constraints that condition the viability of human–robot teaming [

70,

71]. Conversely, the dependent positioning of financial, robot-technology-related, organisational, and social/human barriers suggests that these constraints are frequently symptomatic, intensifying when upstream enabling conditions such as regulatory frameworks, communication protocols, and structured safety practices are underdeveloped. This insight adds nuance to common narratives that frame cost or technology readiness as the principal “first-order” blockers of construction robotics adoption; instead, the present findings suggest that these barriers may be amplified by deeper governance and interaction-design deficits [

39].

Theoretically, these findings strengthen the interpretation of human–robot collaboration as a socio-technical system in which behaviour is shaped by both enabling conditions and constraining structures [

72]. This aligns with the study’s TPB-informed framing; drivers/enablers influence the intention to collaborate through strategic orientation and supportive conditions, while perceived behavioural control is materially constituted by barriers that restrict feasible collaboration. Importantly, the ISM hierarchy indicates that intention and behaviour are unlikely to shift through isolated interventions (e.g., purchasing robots or providing ad hoc training) unless upstream system conditions, particularly regulatory clarity, communication mechanisms, and structured safety governance are addressed in tandem [

73,

74,

75].

Overall, the study extends the prior HRC/HRT literature by moving from a descriptive identification of barriers to a relational and hierarchical explanation of how barriers co-evolve. This systems-level insight provides a more actionable basis for prioritising interventions; rather than treating all barriers as equally addressable, the results suggest that targeting high-driving constraints can generate broader downstream improvements in dependent barriers, ultimately creating more stable conditions for collaborative human–robot teams in construction practice.

5.3. Blended Conceptual Framework of the Profound Barriers to Collaboration in Human–Robot Teams

Mining, manufacturing, agriculture, logistics, and real estate are among the industries that are integrating the use of robotics in their operations [

26,

28]. This has generated a growing interest in research, development, and adoption due to its competitive nature in lowering costs and improving project effectiveness. It helps firms free their workers from repetitive and time-consuming tasks while providing a number of benefits, such as an increased project efficiency and improved accuracy. Compared to traditional processes, robotics adoption strives to improve process performance, efficiency, and scalability while being simple to deploy in a collaborative setting. However, its adoption is not without barriers, as conceptualised in

Figure 7.

As seen in

Figure 6, all the barriers have a high dependency power and are very important. The framework shows that, without legal and regulatory guidelines to provide structured approaches to human–robot collaboration learning, adoption is affected negatively. Also, safety and an enhanced communication interface are critical to encourage social acceptance where humans trust in collaborating with robots on site. The relationship between these barriers reveals that financial, robot technology-related, social, and human and organisational factors are the most important [

16]. The framework reveals that the success of human–robot teams collaborating successfully is highly grounded on effective communication systems in HRI, adequate social incentives, training, and appropriate health, safety, and wellbeing strategies. Also, regulations, policies, and standards to anticipate and guide HRC are critical to its adoption. The international applicability of the proposed framework is ensured through its theory-driven and abstraction-oriented design, rather than through context-specific parameterisation. While construction practices, regulatory regimes, and organisational cultures differ across regions, the barrier categories and their interrelationships identified in this study represent structural and functional constraints that recur across diverse construction systems, including safety governance, regulatory clarity, workforce capability, communication mechanisms, and organisational readiness. By operating at this level of abstraction, the framework does not prescribe uniform solutions but instead provides a diagnostic structure that can be contextualised to specific national, regulatory, or project environments.

Accordingly, the framework is intended to be adapted rather than adopted wholesale, allowing local stakeholders to map region-specific conditions, policies, and practices onto the barrier structure identified in this study. This approach enables cross-context comparability while preserving the sensitivity to local variation, thereby supporting international relevance without neglecting regional specificity.

Table 6 presents a synthesis of key actors involved in mitigating barriers to human–robot collaboration, derived from the recurring roles and responsibilities identified across the reviewed literature. Rather than representing prescriptive assignments, the table consolidates evidence from prior studies that highlight the involvement of governments, regulatory bodies, construction firms, robot developers, and professional institutions in addressing the technological, safety, organisational, and social challenges associated with construction robotics. The allocation of actors to barrier categories reflects patterns consistently reported in empirical and conceptual studies, as well as an alignment with the established industry practices discussed in the literature. The strategies summarised in

Table 7 were developed through a systematic synthesis of mitigation measures and enabling actions reported in the reviewed studies, rather than from the authors’ subjective judgement. These strategies represent commonly cited recommendations, best practices, and policy directions proposed in prior research on construction robotics, safety management, organisational change, and digital transformation. The strategies were subsequently aligned with the barrier categories identified through the ISM analysis to ensure conceptual consistency between the literature-derived barriers and their corresponding mitigation pathways.

By linking barriers identified through systematic review and ISM analysis to actors and strategies consistently discussed in the literature, the framework provides a structured basis for future empirical testing. This approach aligns with prior review-based ISM studies, where strategy formulation is treated as a conceptual outcome that informs subsequent validation through case studies, surveys, or pilot applications.

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Future Research

This study set out to address a critical gap in construction robotics studies; while human–robot collaboration (HRC) is increasingly promoted as a solution to persistent challenges such as low productivity, unsafe working conditions, and labour shortages, there remains a limited systematic understanding of the interdependent barriers that constrain effective collaboration between humans and robots in construction environments. The existing studies have largely examined these barriers in isolation or from narrow disciplinary perspectives, offering a limited insight into how they interact as part of a broader socio-technical system.

To respond to this gap, the study conducted a PRISMA-based systematic review of the extant literature and synthesised the identified impediments to HRC into a coherent, systems-oriented structure. Using a systems thinking approach, a large and fragmented set of barriers was consolidated into eight clearly defined and non-overlapping categories: financial, safety, communication, robot technology-related, organisational, legal/regulatory, education and training, and social and human factors. This consolidation was undertaken to reduce conceptual ambiguity and minimise subjective bias, particularly in light of the variations in methodological rigour and respondent expertise reported in earlier studies.

Building on this synthesis, an interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach was applied, informed by expert insights, to examine the hierarchical and causal relationships among the identified barrier categories. The resulting framework reveals that challenges to human–robot collaboration are not driven by isolated technological limitations alone, but by a complex interaction of regulatory, organisational, behavioural, and technical factors. On the basis of these structured relationships, the study proposed a set of integrated strategies aimed at mitigating the most influential barriers and enabling more effective collaboration within human–robot teams in construction. Therefore, this research makes a valuable contribution to the existing body of knowledge on HRC development and holds implications for both theoretical understanding and practical applications.

This study serves as an initial step in enhancing construction professionals’ understanding of the industry’s perception of risks and barriers to collaboration in human–robot teams. Gaining this insight can aid in developing risk-mitigation strategies and fostering confidence in technology, ultimately promoting the adoption of human–robot teams within the construction sector. It helped to highlight, from a theoretical standpoint, the intricacies of the limitations that prohibit partnerships in the general use of HRC and HRT. It also contributes to the existing body of literature by analysing and mapping the holistic interconnections among the barriers. Specifically, the findings emphasise the importance of adopting integrated strategies and enablers to mitigate these challenges. Furthermore, the study highlights effective techniques for addressing different categories of barriers.

In addition, the findings underscore that the successful implementation of human–robot teams in construction is not driven by isolated technological advancements alone, but by the alignment of organisational readiness, regulatory clarity, workforce capability, and communication structures. By explicitly revealing the hierarchical and interdependent nature of these barriers, the study provides a systems-level perspective that can support more informed decision-making when prioritising interventions for human–robot collaboration in practice.

Limitations of the Study

The framework was not tested in a real-world construction context because the primary objective of this study was theory development and structural explanation, rather than empirical validation. Given the fragmented and context-dependent nature of human–robot collaboration adoption in construction, this study deliberately adopts a systematic review-driven and expert-validated ISM approach to establish a foundational and transferable framework. Such theory-building is a necessary precursor to field-based testing, as it clarifies the interdependencies among barriers and provides a structured basis for designing, selecting, and evaluating empirical interventions in subsequent applied studies.

Practical and Theoretical Implications of the Study

The ISM–MICMAC results provide actionable guidance for prioritising interventions based on driving and dependence relationships. For policy-makers and regulators, the identification of legal/regulatory and communication factors as upstream drivers implies that progress will depend on clearer guidance for human–robot work arrangements, accountability, liability, and compliance requirements, alongside minimum standards for safe interaction and communication protocols on site. For clients and project owners, the findings suggest that procurement and contract structures should explicitly require robot integration planning, competence verification, safety assurance processes, and communication responsibilities across the supply chain, rather than treating robotics as an optional add-on.

For construction contractors and organisational leadership, the model indicates that efforts should begin with workforce capability development and structured safety governance, including task redesign, competency-based training, change management, and site-level procedures that define human–robot roles, supervision, and escalation pathways. For robot developers and technology providers, the results highlight the need to prioritise usability, transparent interaction feedback, and safety-by-design features that support real-time collaboration in dynamic site conditions, while enabling straightforward integration into construction workflows. Finally, professional bodies, training institutions, and insurers have a role in setting competency benchmarks, supporting certification pathways, and developing risk assessment and assurance mechanisms that can reduce the perceived uncertainty and strengthen trust in collaborative deployment.

From a theoretical perspective, the study contributes to the HRC literature by integrating the Theory of Planned Behaviour with interpretive structural modelling to capture both behavioural intent and structural constraint. By conceptualising attitudes towards behaviour as enabling strategies and perceived behavioural control as a systemic barrier, the study operationalises TPB in a manner that reflects the organisational and institutional realities of construction projects. This reinterpretation addresses a limitation of traditional technology acceptance models, which often focus on individual perceptions while underrepresenting regulatory, organisational, and inter-organisational dynamics. The ISM–MICMAC approach complements behavioural theory by revealing how these dynamics interact hierarchically, thereby offering a more holistic explanation of collaboration outcomes in complex socio-technical systems

Areas for Future Studies

Future research should move beyond conceptual modelling by undertaking a context-specific empirical validation of the proposed framework through (i) multi-country surveys of construction robotics/HRC experts to test the relative salience and interaction of barriers across regulatory and cultural settings; (ii) in-depth case studies and pilot implementations on live projects (including SMEs and large contractors) to observe how communication protocols, safety governance, and training structures influence collaborative performance; and (iii) a structured evaluation of intervention packages (e.g., “regulatory clarity, training, communication interface design”) using measurable outcomes such as incident rates, task productivity, near-miss reporting, worker trust, and adoption intent.

In addition, rigorous techno-economic assessment is needed to quantify ROI under different deployment scenarios, including the cost of integration planning, training, insurance, downtime, and safety assurance measures. Despite the successful achievement of the study objectives, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study adopts a generalised and theory-driven perspective in identifying and structuring barriers to human–robot collaboration, which does not explicitly account for regional, regulatory, or organisational variations across construction contexts. While such generalisation may obscure localised nuances, it is methodologically appropriate at this stage, as it enables the development of a transferable systems-level framework that can subsequently be contextualised to specific countries, project types, or industry segments. Second, the study is based on a systematic synthesis of the existing literature and expert-validated structural modelling, rather than primary empirical data drawn from live construction projects. Consequently, the proposed strategies should be interpreted as conceptual and explanatory rather than prescriptive solutions that have been empirically validated in practice. This limitation reflects the emergent nature of human–robot collaboration in construction, where large-scale implementation and empirical datasets remain limited.

Accordingly, future research should focus on a context-specific empirical validation of the proposed framework through surveys, case studies, and pilot implementations within real construction environments. Such studies would allow for the refinement, prioritisation, and testing of the identified strategies under different regulatory, cultural, and operational conditions, including applications within global construction SMEs, thereby strengthening their practical relevance and generalisability.

Barriers j

Barriers j  Barriers i

Barriers i