1. Introduction

In recent years, quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have emerged as a pivotal platform for autonomous operations due to their structural simplicity, vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capability, and versatility in constrained environments [

1,

2]. Their ability to hover, maneuver precisely, and operate both indoors and outdoors has made them indispensable across diverse domains, including environmental monitoring, surveillance, search and rescue, and infrastructure inspection [

3,

4].

Despite these advantages, achieving real-time flight path tracking of dynamic targets such as mobile ground vehicles or rovers remains technically challenging. This complexity arises primarily from the underactuated and nonlinear dynamics of quadrotors, coupled with the unpredictable nature of real-world environments [

5,

6]. Effective tracking demands not only rapid response to abrupt target maneuvers but also robust adaptation to external disturbances such as wind gusts, terrain variability, and communication noise [

7].

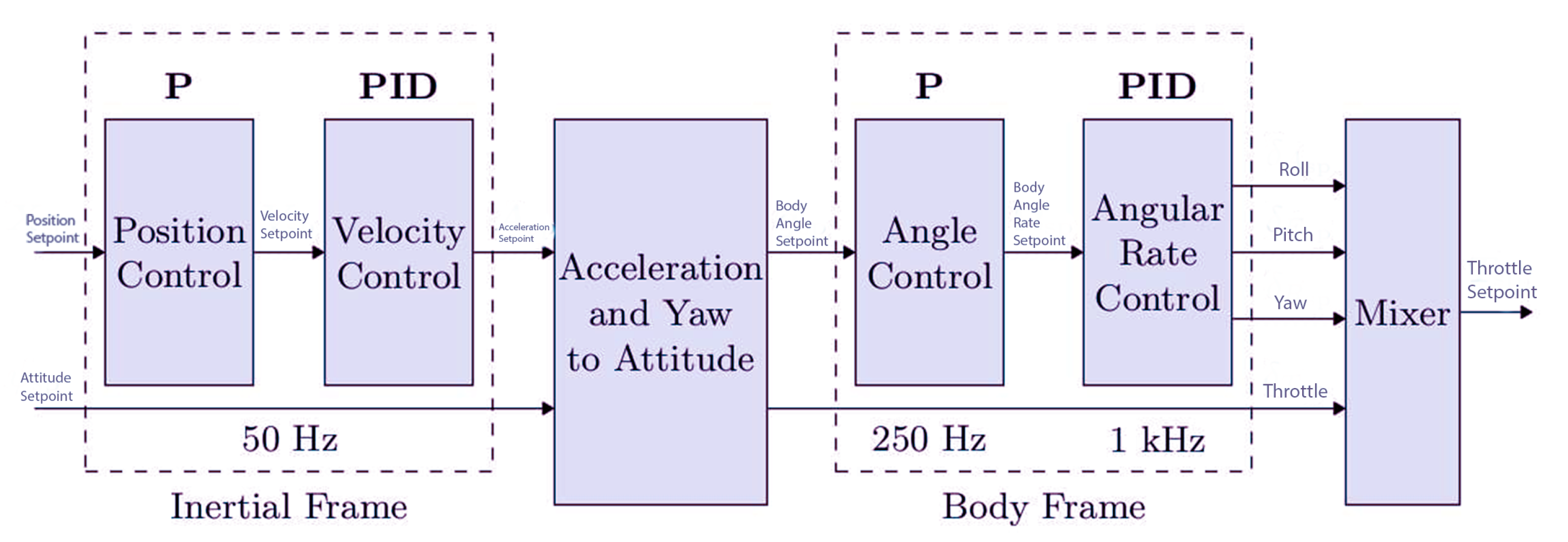

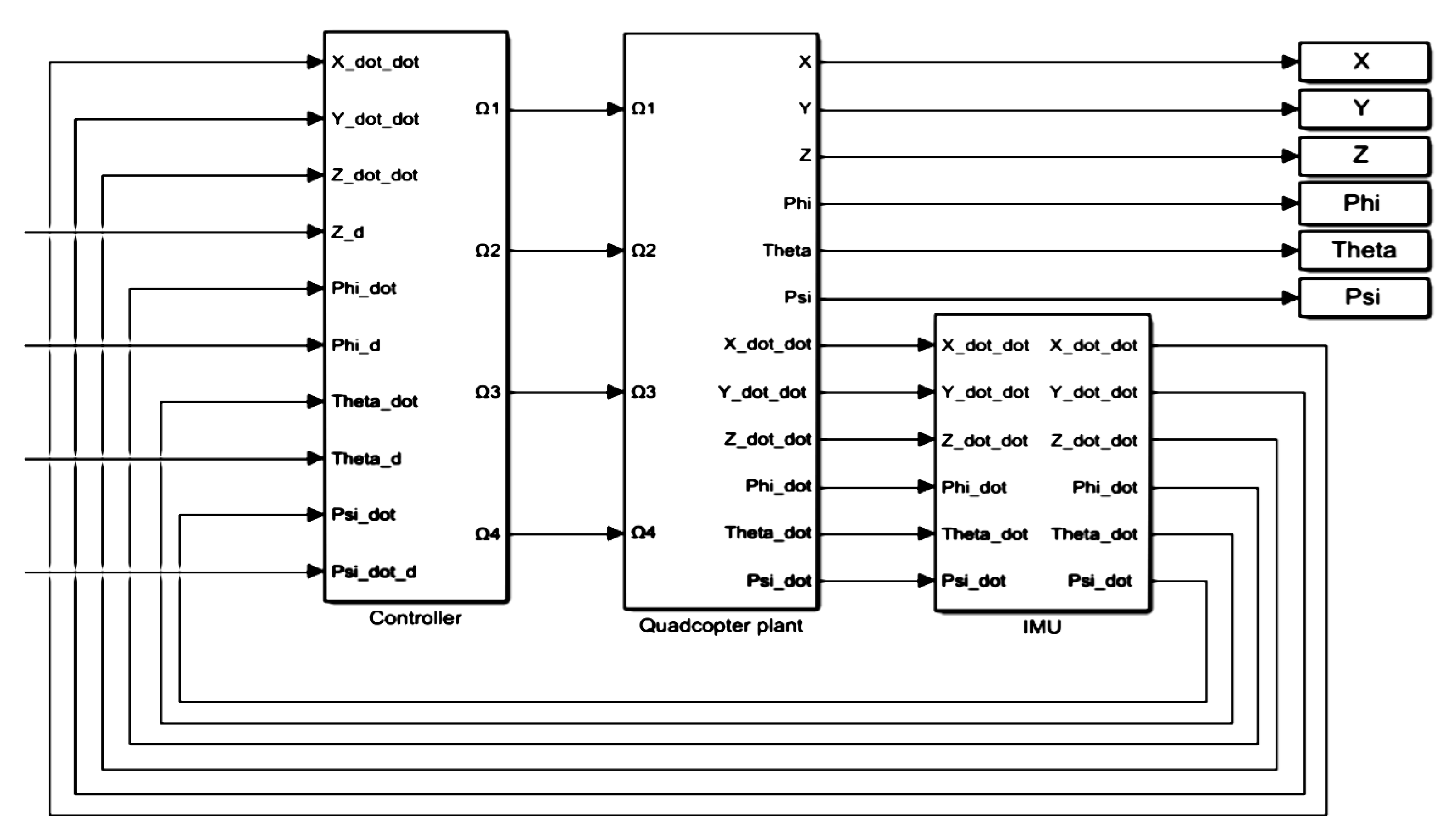

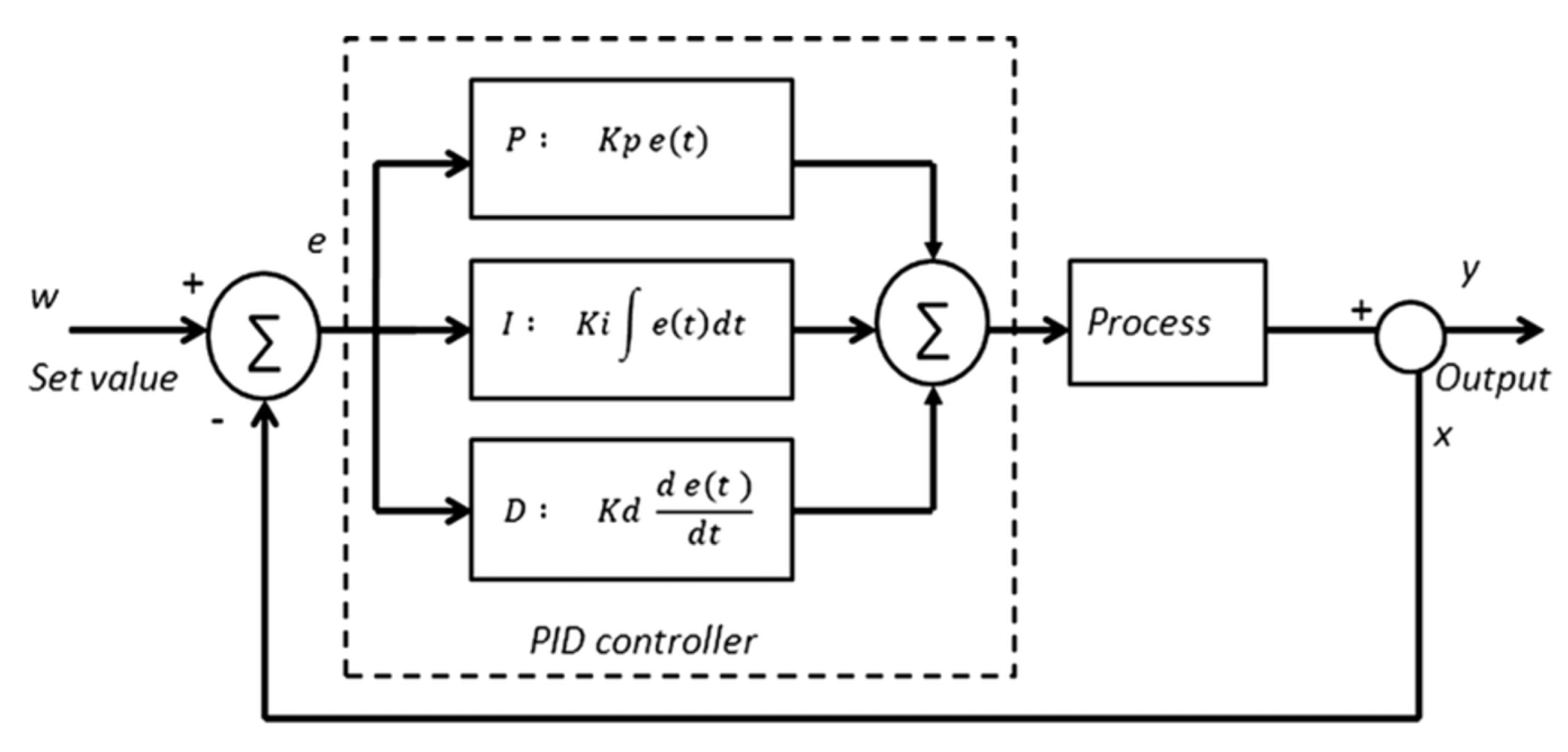

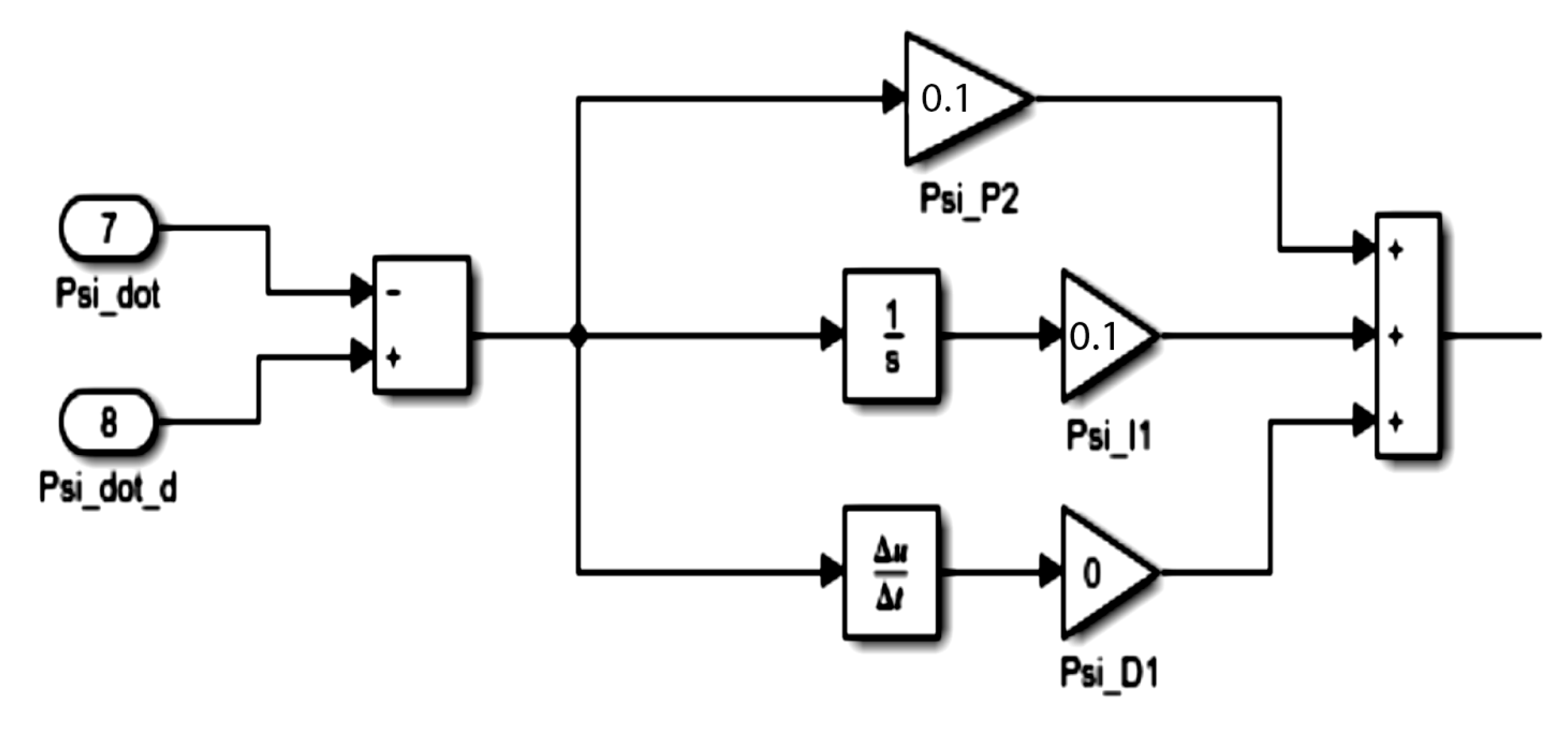

Traditional control techniques, such as the Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controller, have been extensively employed for UAV stabilization owing to their simplicity and ease of implementation [

8,

9]. However, in highly dynamic or uncertain environments, classical PID controllers often fall short due to their fixed gains and limited predictive capability [

10]. Recent research has therefore focused on augmenting conventional controllers with nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC) and machine learning (ML) approaches to enable real-time adaptive behavior and enhanced robustness [

11,

12].

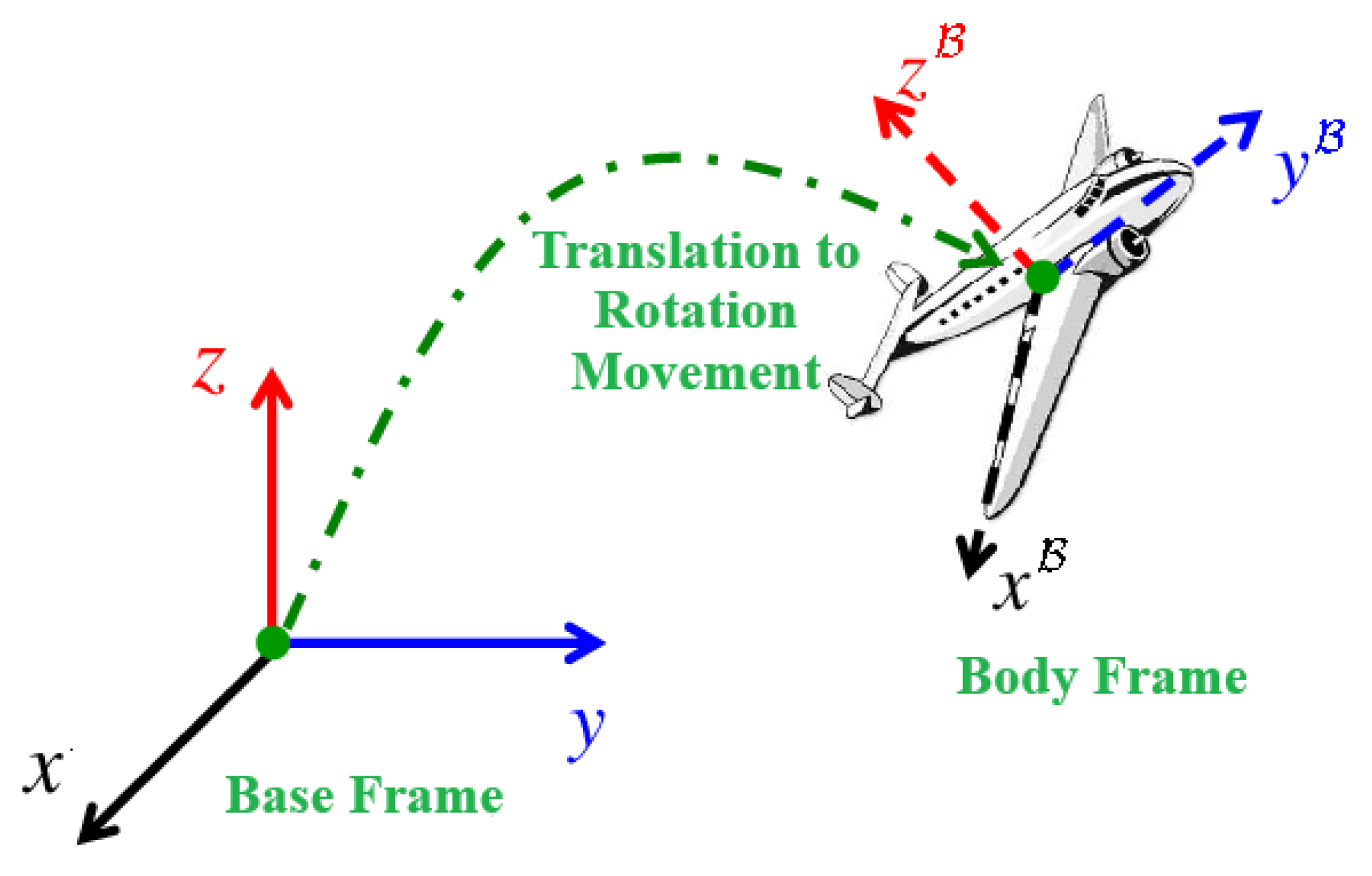

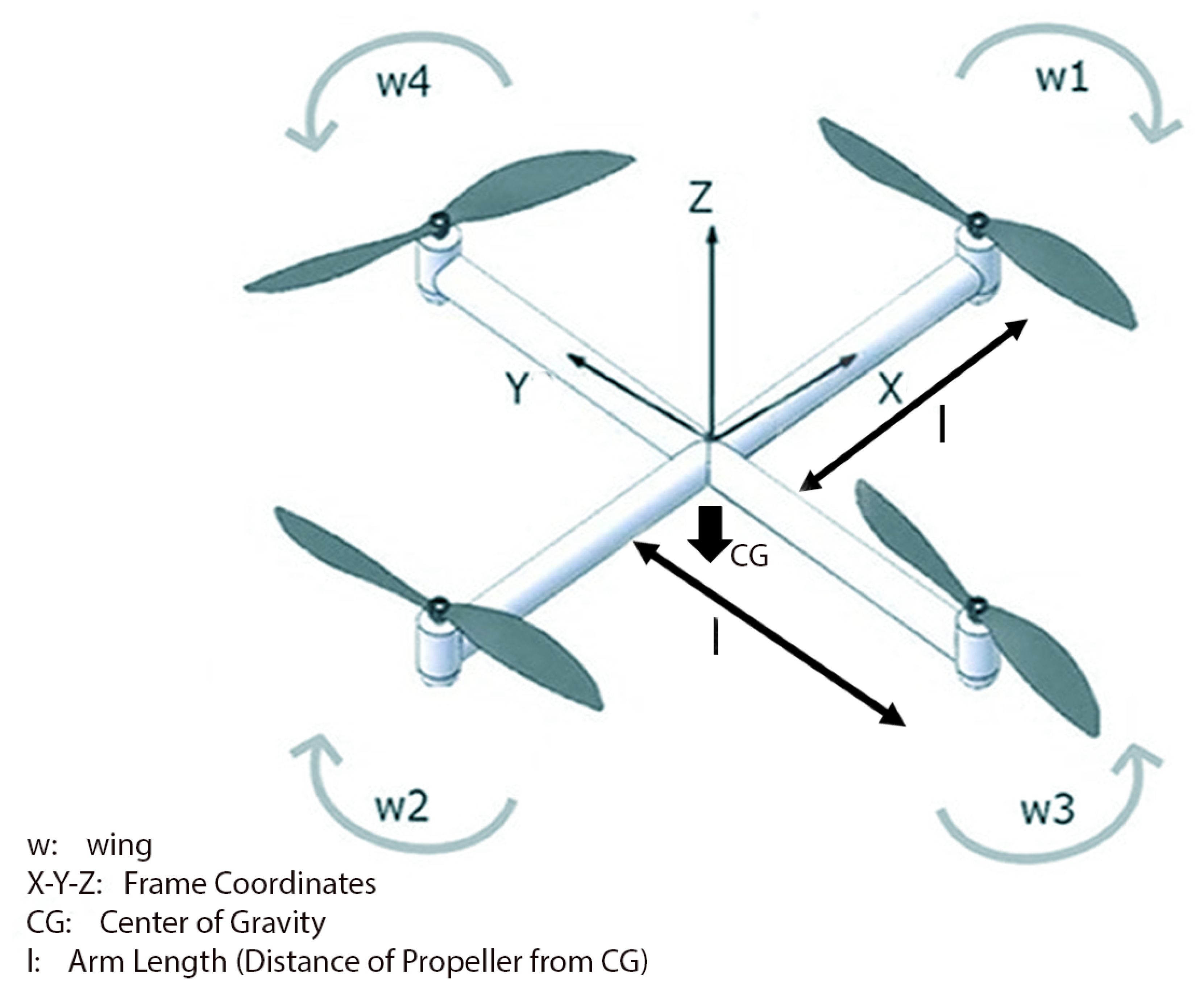

Trajectory generation represents another crucial aspect of flight path tracking. The minimum snap trajectory approach proposed by Mellinger and Kumar [

13] minimizes the fourth derivative of position (snap) to ensure smooth motion, particularly during aggressive maneuvers or high-speed tracking. The quadrotor platform considered in this work is illustrated in

Figure 1. For completeness,

Figure 1 provides a structural view of a typical quadrotor platform used in related experiments. When integrated with vision-based localization [

14] and reinforcement learning techniques [

15], UAVs gain the ability to perceive and adapt to their surroundings, enabling autonomous operation in complex and dynamic environments. Furthermore, advancements in vision-based human tracking for mobile-robot following have been demonstrated through the improved stereo-vision method presented in [

16].

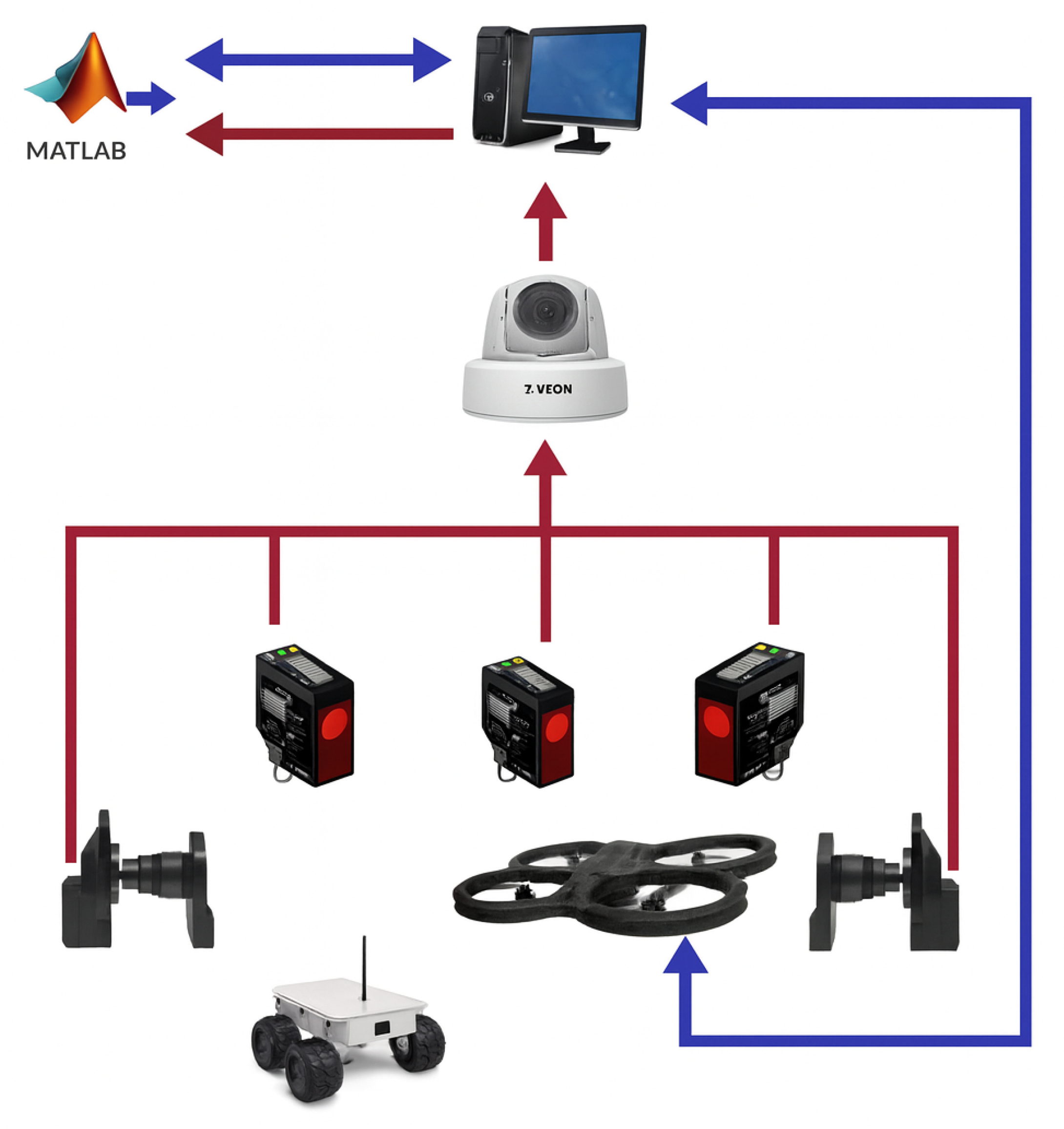

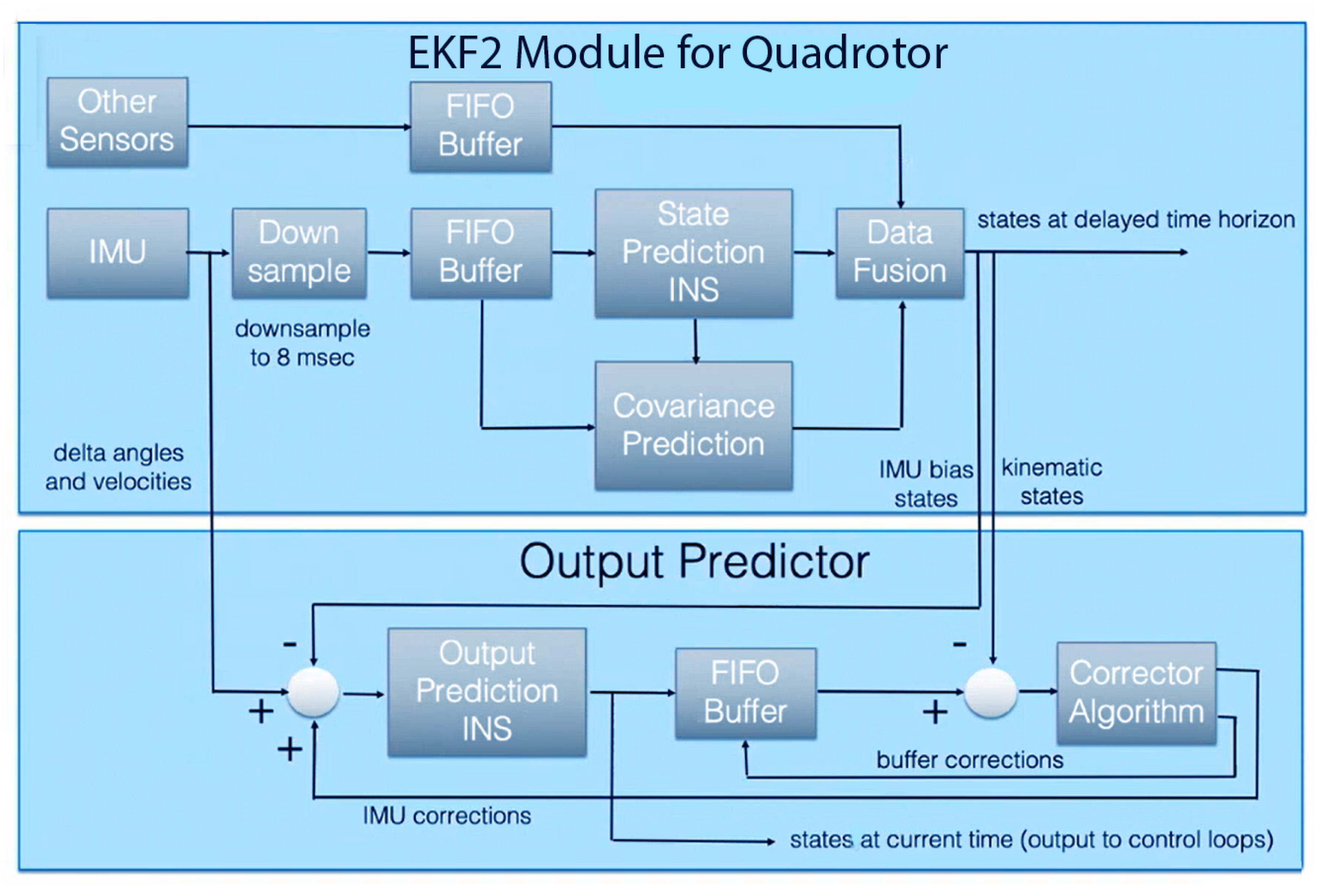

As shown in

Figure 2, the sensing configuration used in prior experimental work provides context for our tracking formulation.

Numerous experimental studies have validated these control strategies. For instance, motion-capture-based tracking systems, such as the VICON-based framework presented in [

17], have demonstrated precise three-dimensional tracking using external sensors. The referenced study developed an autonomous mobile object tracking system utilizing a UAV integrated with a motion-sensing platform as shown in

Figure 2. This work significantly advances UAV-based object tracking capabilities, particularly in real-time applications, and holds broad potential for diverse domains such as target tracking, environmental monitoring, and surveillance in dynamic environments.

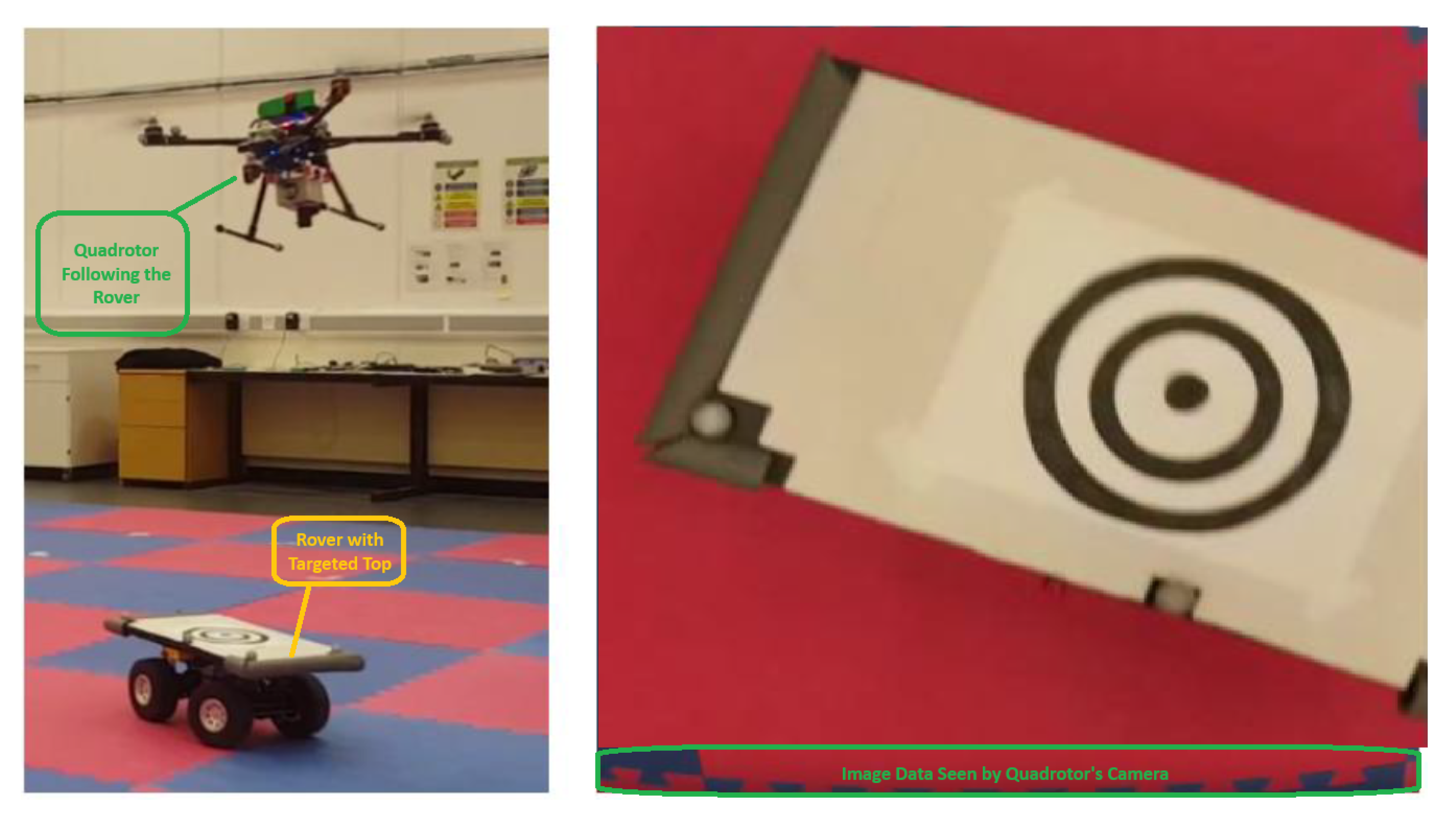

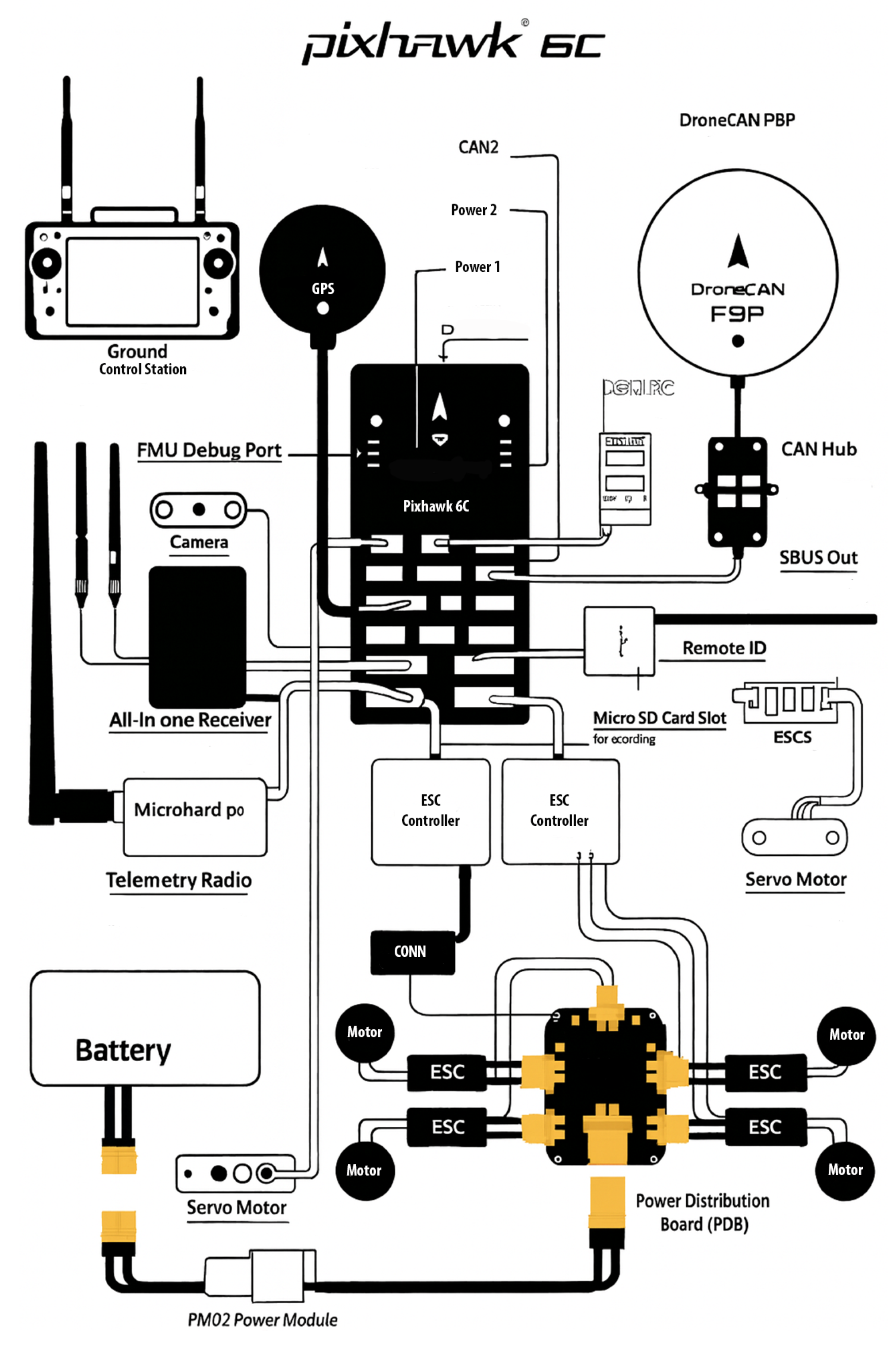

Similarly, Greatwood et al. [

18] incorporated a neuromorphic vision sensor to achieve the low-latency and energy-efficient visual tracking of ground vehicles as illustrated in

Figure 3, which is adapted from their work. Furthermore, UAV-UGV coordination systems, such as the takeoff-and-landing-on-mobile-robot framework proposed by Zou and Dai [

19], have demonstrated how real-time computer vision and wireless communication can effectively enable cooperative aerial–ground robotic operations.

The rapid advancement of machine learning (ML) techniques has further expanded the capabilities of UAV control systems. Methods such as Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) enable quadrotors to acquire agile behaviors, such as flips and obstacle avoidance, in simulated environments before being transferred to real-world applications [

20]. Neural Networks (NNs) have also demonstrated considerable potential in modeling aerodynamic disturbances and wind effects, thereby improving quadrotor flight stability [

21]. Furthermore, imitation learning, as explored in [

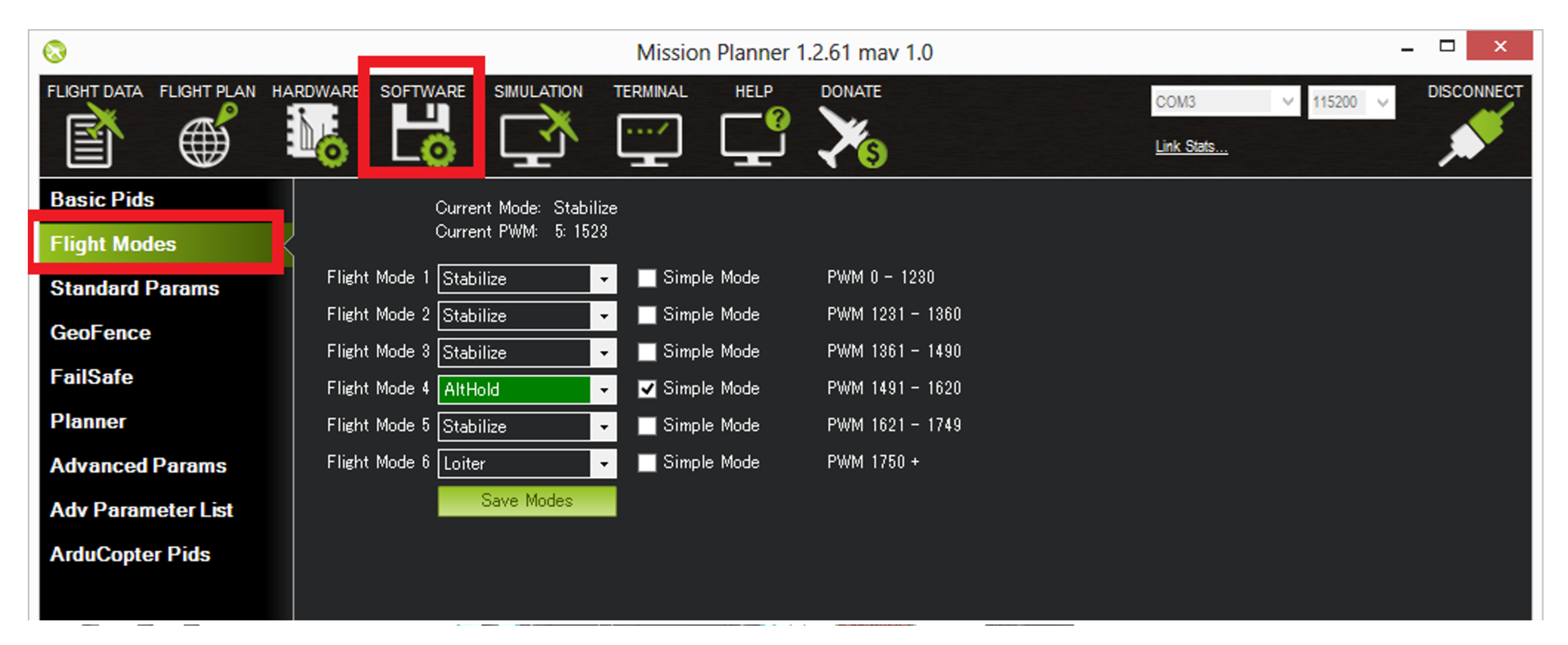

21], offers a data-efficient alternative by allowing UAVs to replicate expert demonstrations with limited training data. It is important to note that, unlike the ML-based control strategies discussed in the prior literature, our implementation does not use any machine learning component in the flight control loop. Pixhawk executes classical cascaded PID control with fixed gains, while its adaptive elements (autotune, hover-throttle learning, and dynamic notch filtering) are estimator based rather than ML based.

A broad range of studies on UAV tracking systems have significantly contributed to understanding the challenges and potential solutions for enhancing object-tracking accuracy in demanding operational environments. For example, the research presented in [

22] applied a leader–follower paradigm using GPS and Arduino microcontrollers for outdoor UAV coordination. The study also introduced an algorithm for an indoor micro-quadrotor that employs a vision-based approach to track lines. This technology uses an integrated vision camera to detect line information, which is then transmitted to a ground control station (GCS) for real-time image processing.

Additionally, the work by Sharma and Singh [

23] investigated the coordination between a UAV and a small mobile vehicle. Their study proposed a vision-based control strategy for ground-target following, utilizing an advanced vision sensor architecture equipped with an independent processing unit for each pixel, thereby enabling high-speed visual computation and enhanced target-tracking performance.

Correspondingly, it has been demonstrated that employing multiple quadrotors, rather than a single unit, offers several advantages. Multi-quadrotor systems can carry additional sensors and payloads, enhance cargo and surveillance capabilities, and accomplish complex or time-intensive missions with greater efficiency. Quadrotor formation control typically employs one of several coordination strategies, including the following:

Among these, the Leader–Follower configuration is the most straightforward, wherein one quadrotor assumes the role of leader while the others act as followers. Each follower quadrotor maintains a predefined relative position and adjusts its motion according to the leader’s trajectory [

23].

Despite these advancements, significant challenges persist. Many existing systems still lack real-time responsiveness, struggle in GPS-denied environments, or depend on computationally intensive algorithms unsuitable for onboard processors. Furthermore, communication delays, control-loop latency, and environmental uncertainties continue to hinder consistent and reliable tracking performance [

24,

25,

26].

This research aims to address these limitations by developing a hybrid UAV control architecture that integrates an adaptive-tuning framework that relies on Pixhawk’s estimator-based mechanisms (autotune, hover-throttle learning, and dynamic notch filtering) to maintain robustness under delay and disturbances, without any machine learning PID tuning. The proposed system is designed to perform the following:

Ensure real-time communication with minimal latency;

Accurately follow a moving rover across variable terrains;

Maintain stability across altitude, pitch, yaw, and roll axes;

Adapt to obstacles, wind disturbances, and directional variations in the target’s trajectory.

Novelty and Contributions: The study develops a delay-aware hybrid PID control framework that integrates classical feedback regulation with Pixhawk’s estimator-based adaptive mechanisms (autotune, hover-throttle learning, and dynamic notch filtering) to mitigate communication latency between a UAV and a ground rover. The approach is analytically verified through Padé-modeled delay analysis and Routh–Hurwitz stability criteria, and experimentally validated under a measured delay of 8.2 ms. Field trials confirm sub-meter trajectory accuracy (mean = 0.82 m) and robust attitude stabilization (yaw error ≤ 1.3°) across dynamic outdoor conditions. Compared with nonlinear MPC and 2-DOF PID controllers, the framework achieves comparable tracking precision with substantially lower computational overhead, thereby establishing a computationally efficient and field-validated framework for real-time UAV-UGV cooperative tracking missions.

Building on this foundation, the control strategy combines the predictability of classical PID regulation with the adaptability of Pixhawk’s estimator-based autotuning mechanism to enable reliable real-time UAV-UGV coordination. The proposed framework’s effectiveness is validated through both simulation and real-flight experiments, demonstrating strong potential for applications in autonomous navigation, disaster response, smart agriculture, and security surveillance.

5. Experimental Results and Discussion

This section presents the experimental validation of the autonomous quadrotor’s capability to track mobile ground targets. The experiments provide a comprehensive assessment of real-world performance by evaluating tracking accuracy in the

plane, altitude stability along the

Z-axis, attitude precision (yaw, pitch, and roll), and geographic coordinate consistency. Field tests were conducted in Al Ain City, with video documentation provided in [

43].

To ensure consistent comparison between the simulation framework and real-flight validation, a unified set of key performance indicators (KPIs) is adopted throughout this section. These KPIs include the following:

Using the same KPI set for both simulation and experiments resolves the mismatch between earlier transient-based simulation metrics and RMS-based experimental reporting, enabling direct performance comparison across all evaluated scenarios.

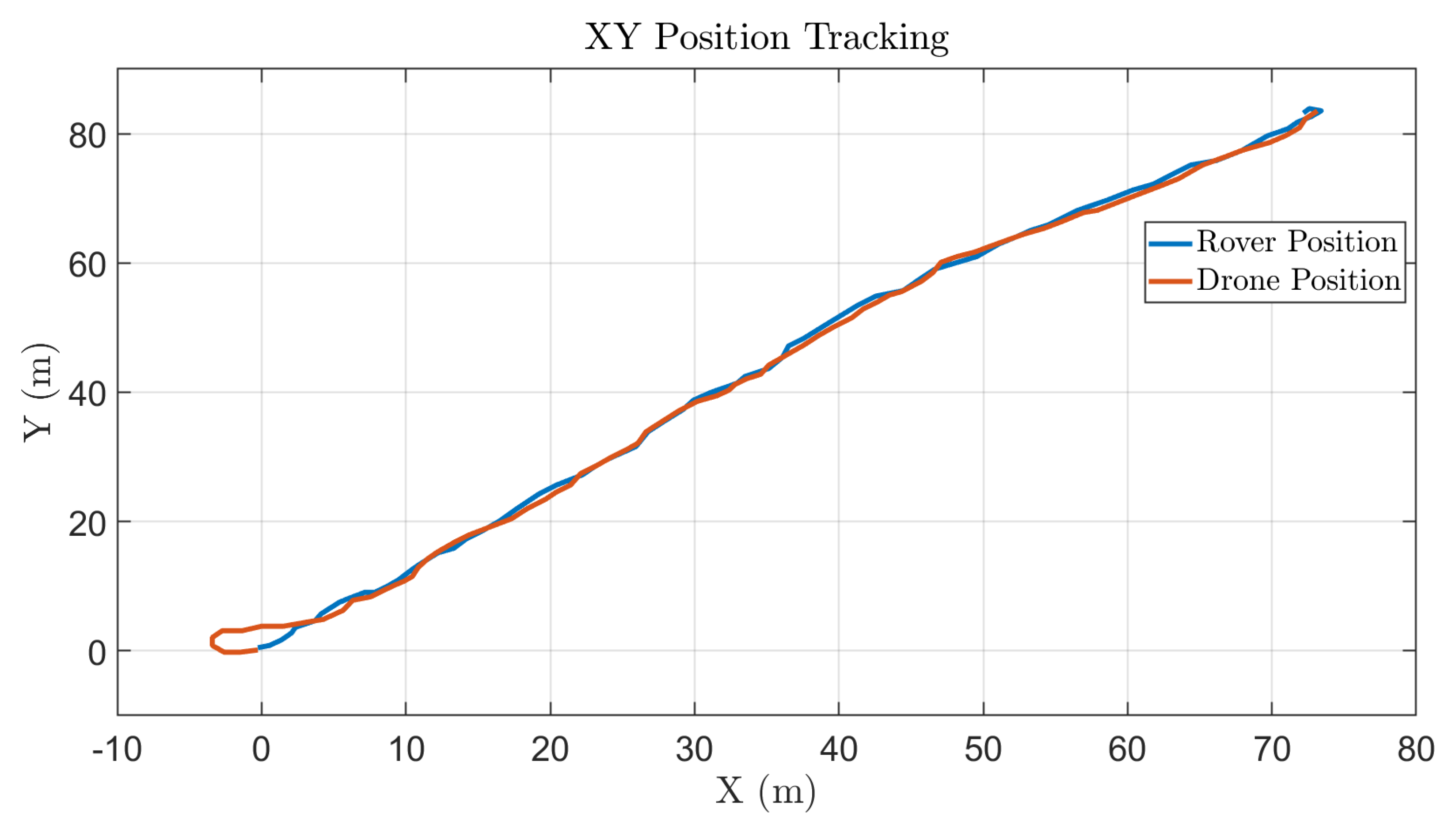

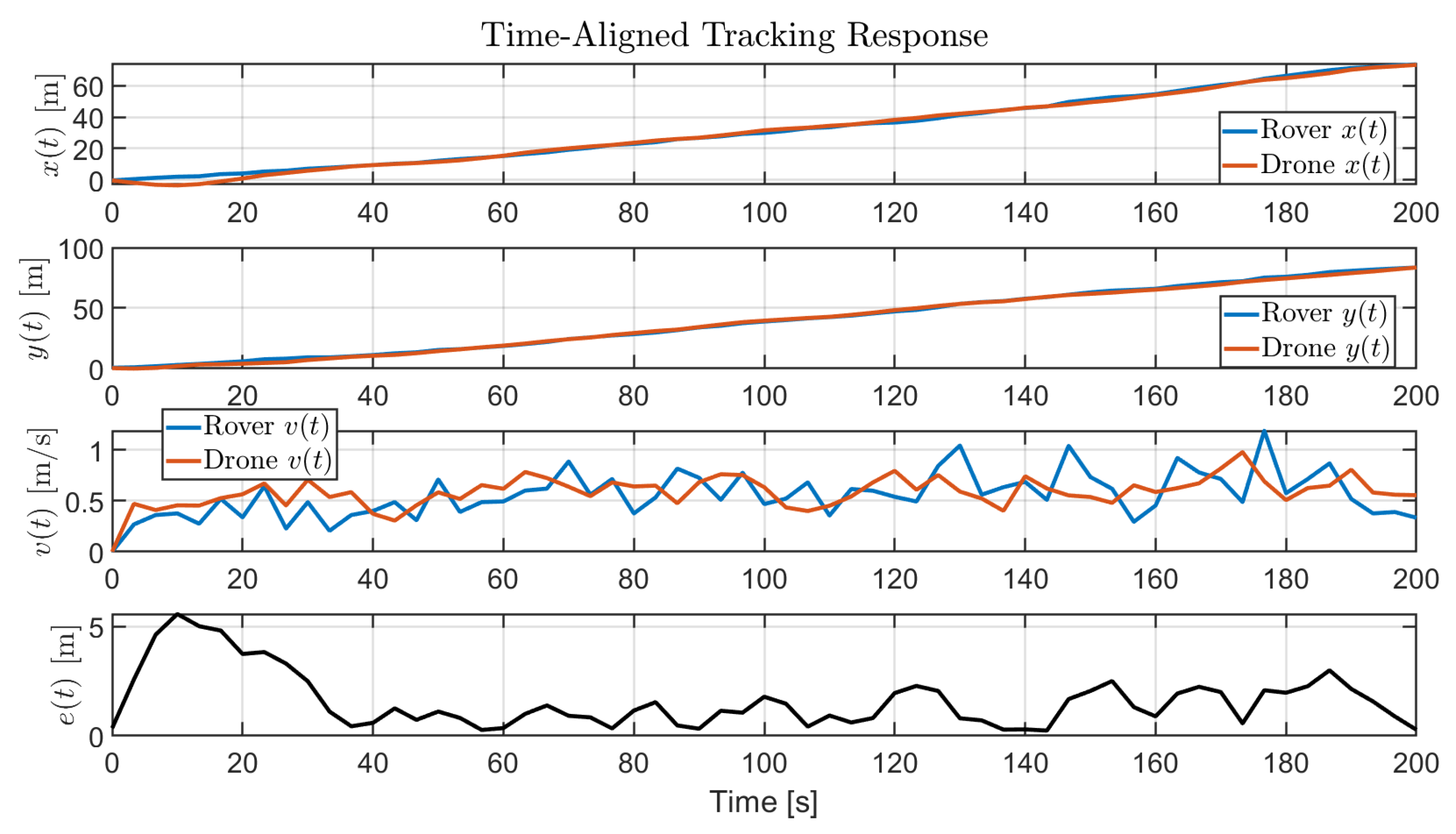

5.1. XY Plane Tracking Performance

The experimental setup comprised a mobile ground rover acting as the target, which continuously transmitted its real-time position to the quadrotor. The onboard control system processed this data at a sampling rate of 20 Hz. To ensure robust and realistic validation, all experiments were conducted outdoors over varying terrain and environmental conditions. The

positional states of both the rover and the drone are illustrated in

Figure 21 and analyzed in the following discussion.

5.1.1. Quantitative Analysis

The results indicate a strong correlation between the drone and rover trajectories, with an average tracking error below 1 m and a maximum deviation of 2.15 m. The high correlation coefficient () confirms excellent path-following performance and synchronization accuracy in dynamic motion.

5.1.2. Error Sources

A complete understanding of the drone’s real-world performance requires analyzing the factors contributing to observed deviations. The system experienced a consistent communication latency of approximately 0.98 ms and a short initialization delay during calibration. In addition, environmental influences such as wind gusts measured at up to 4.2 m/s introduced mild positional fluctuations. These effects collectively highlight the importance of incorporating real-time latency compensation and robust disturbance-rejection mechanisms in future implementations.

It is important to note that the present experiments were conducted under moderate wind conditions (up to 4.2 m/s) with standard GPS availability and low to medium target speeds. Due to airspace safety restrictions and hardware limitations of the current platform, controlled testing under strong wind fields (5–8 m/s), GPS-denied operation, and tracking of high-speed ground targets (3–8 m/s) was not feasible in this study. These conditions represent important next-stage scenarios for expanded validation.

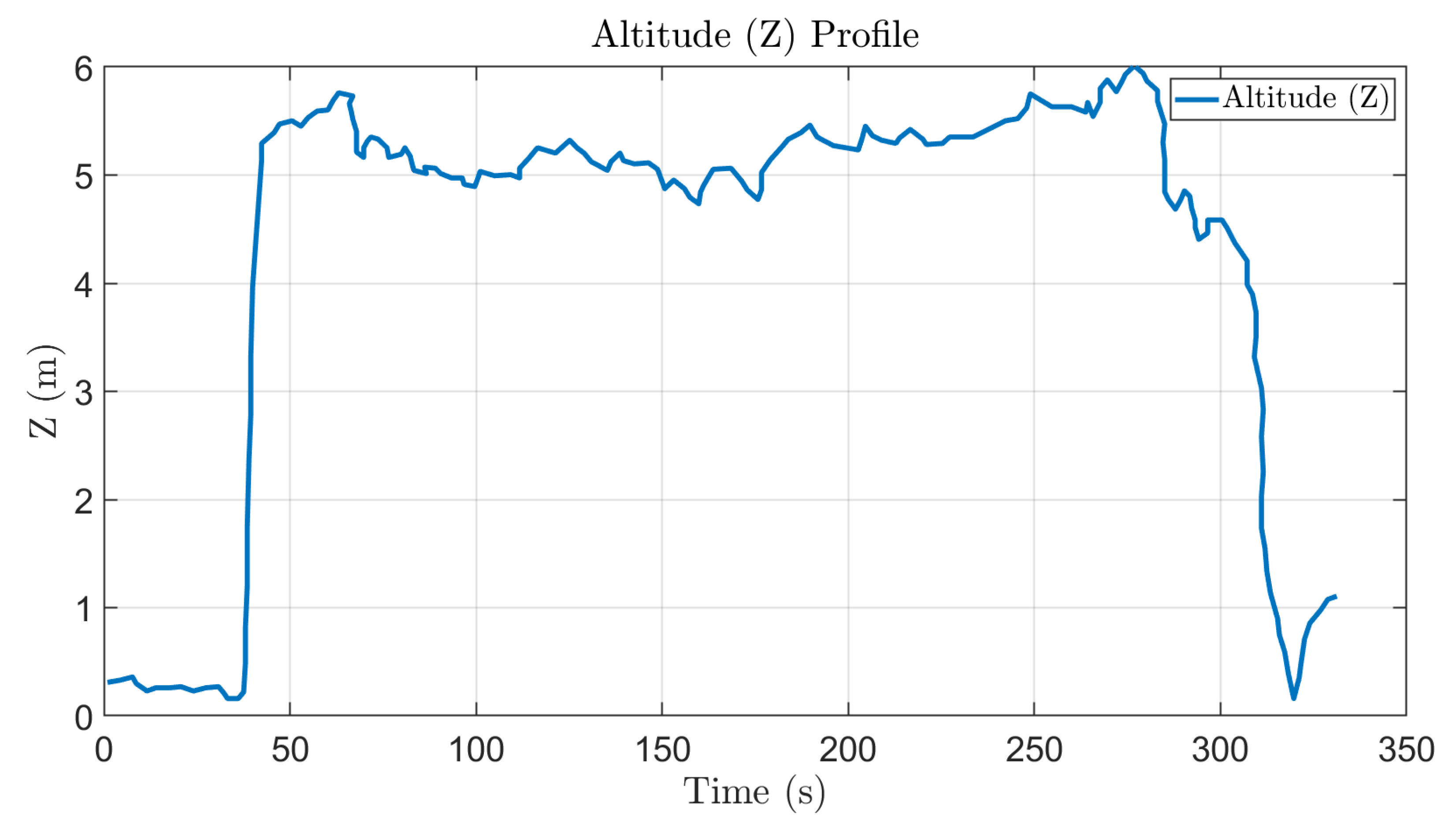

5.2. Altitude Control Analysis

The altitude profile presented in

Figure 22 demonstrates a highly responsive and stable vertical control system. The quadrotor achieved a target altitude of 5 m within 2.8 s, corresponding to an average climb rate of 1.79 m/s. During steady flight, the mean altitude was maintained at 5.12 m with a low standard deviation of 0.43 m, indicating effective compensation against vertical disturbances. The 95% percentile range (4.35–5.89 m) confirms that altitude deviations remained within acceptable operational limits. A smooth and controlled descent was achieved at a rate of 0.91 m/s, demonstrating precise control authority during landing. Overall, these results verify the robustness and responsiveness of the altitude control subsystem under realistic flight conditions.

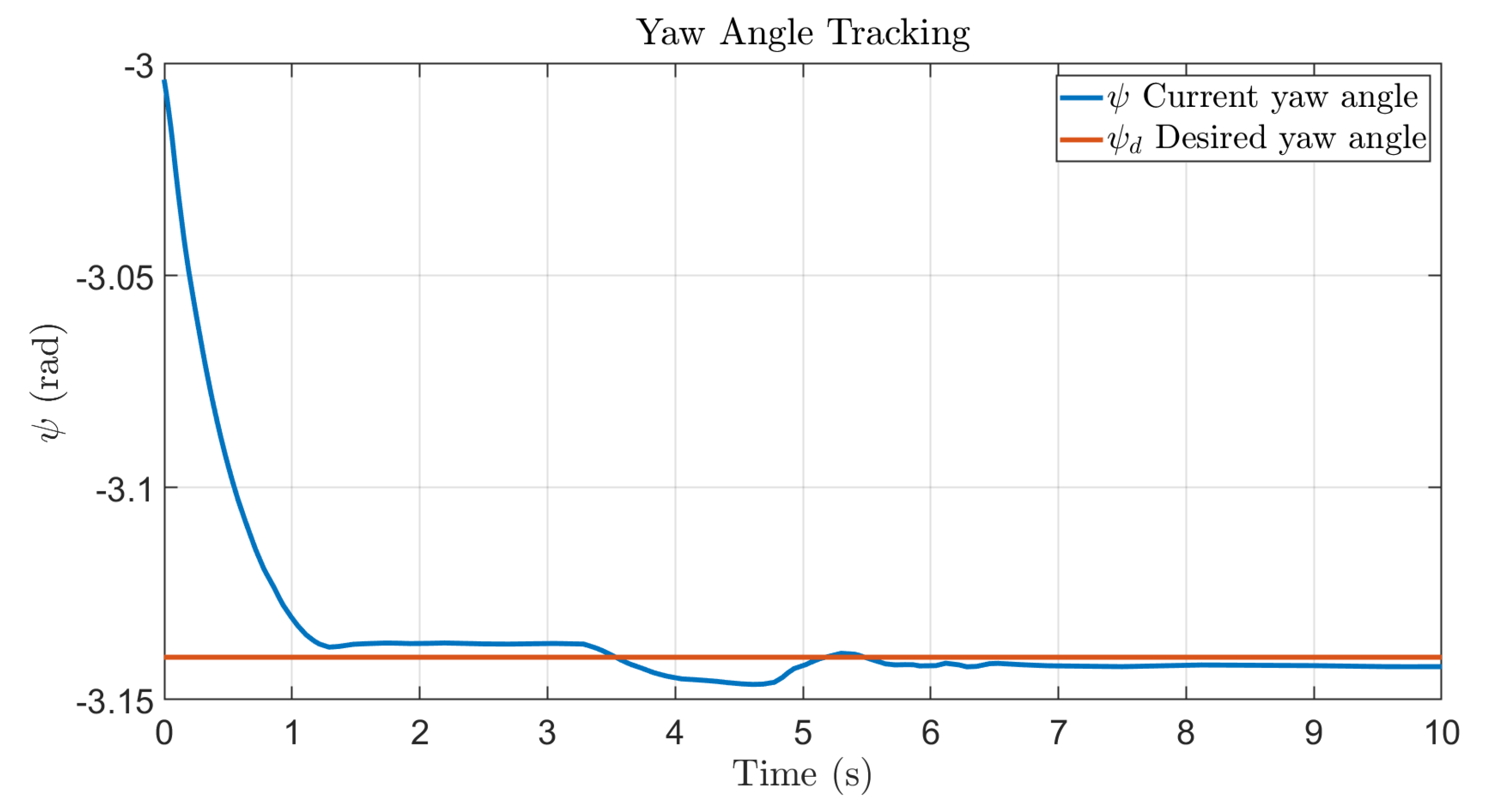

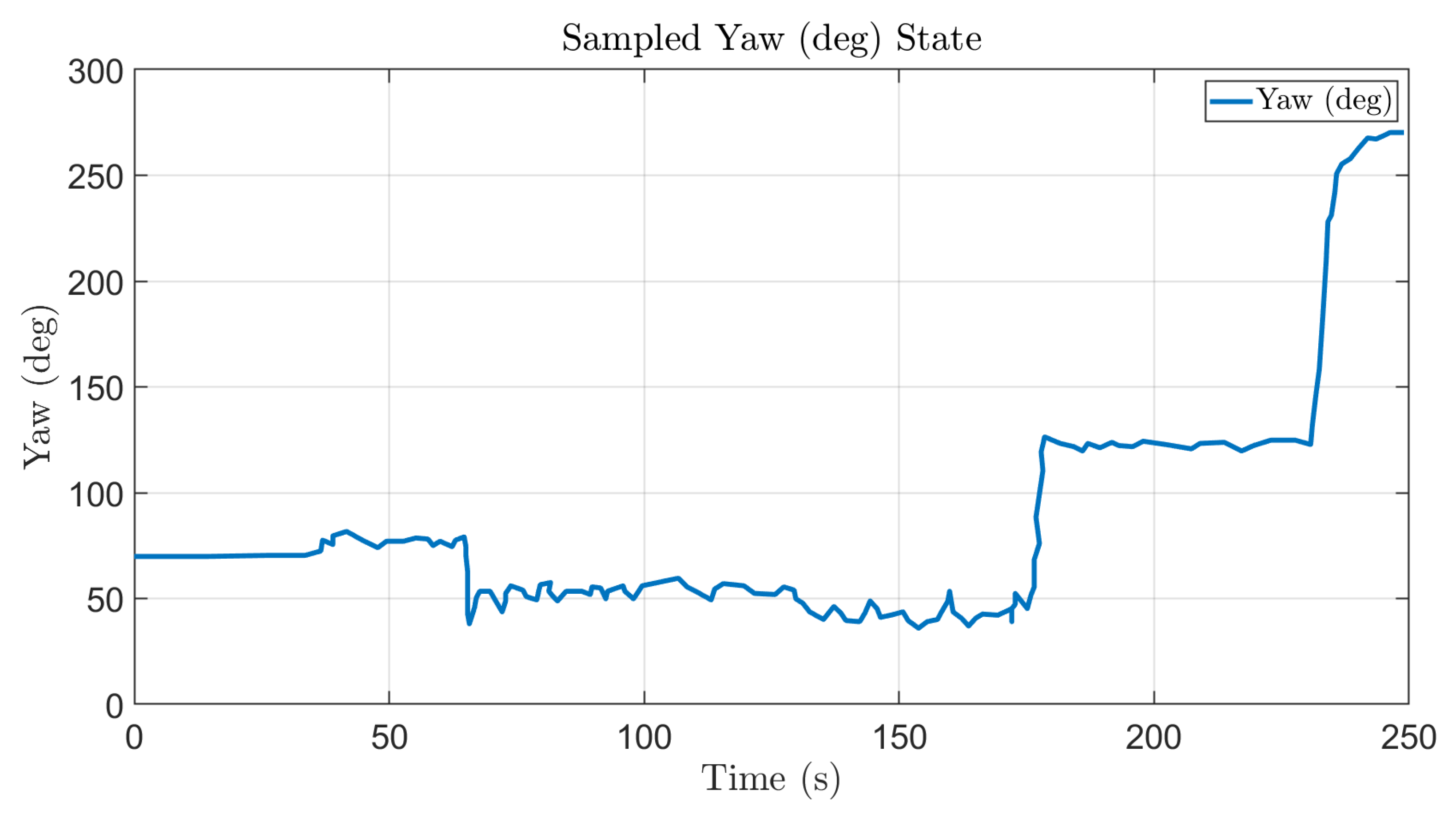

5.3. Yaw Control Performance

The yaw tracking performance, illustrated in

Figure 23, provides insights into the rotational stability and responsiveness of the control system. The quadrotor exhibited rapid convergence to the commanded yaw angle, achieving a settling time of 1.8 s within a ±5° tolerance band. However, a peak overshoot of 12.7° was observed, suggesting a slightly underdamped response that may benefit from fine-tuning of the controller gains. Despite this transient behavior, the system achieved a steady-state error of only 1.3°, confirming its ability to maintain precise orientation control over extended operation. Collectively, these results demonstrate a highly responsive yaw control system that achieves fast stabilization and accurate heading retention, with minor trade-offs in overshoot behavior that can be mitigated through adaptive tuning strategies.

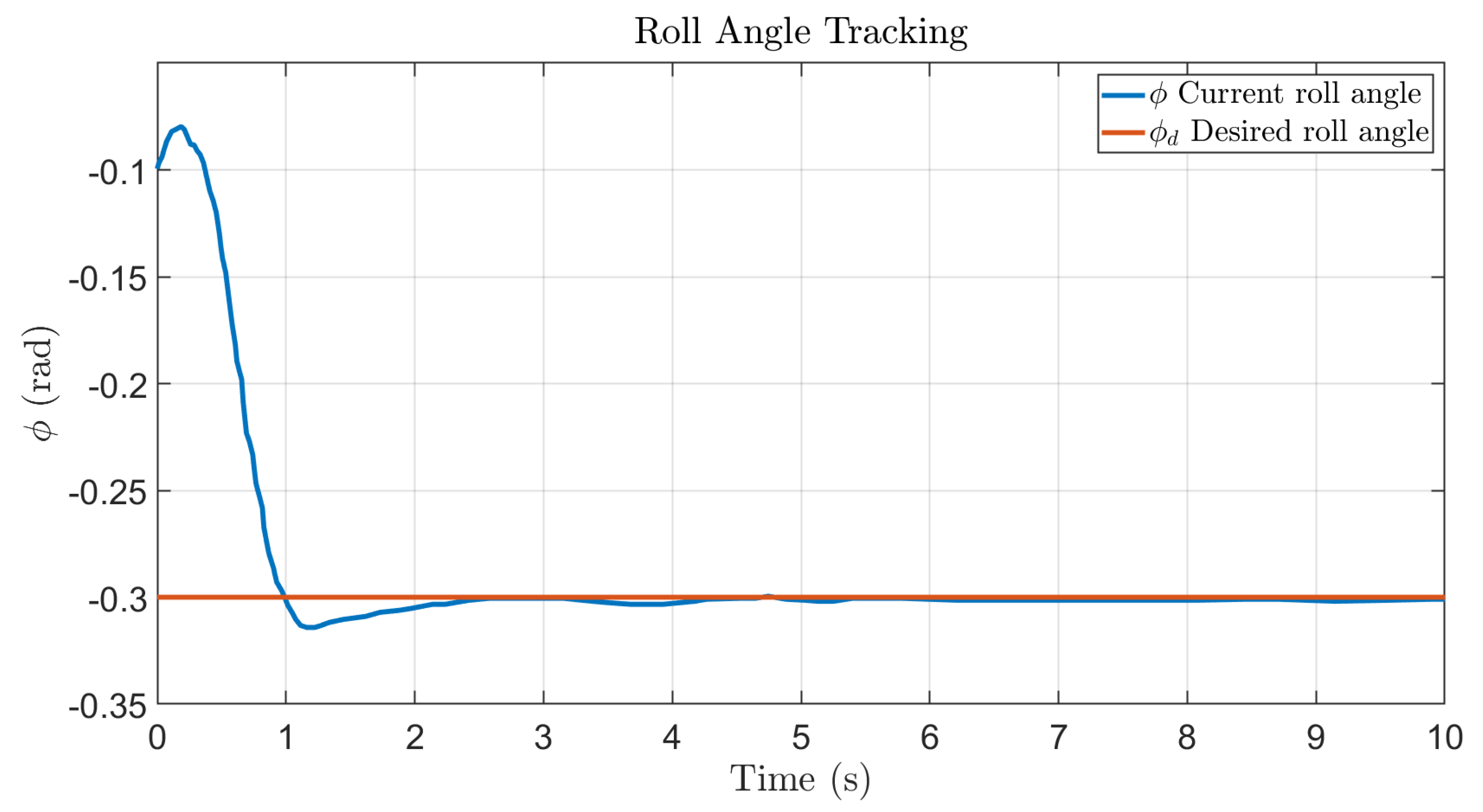

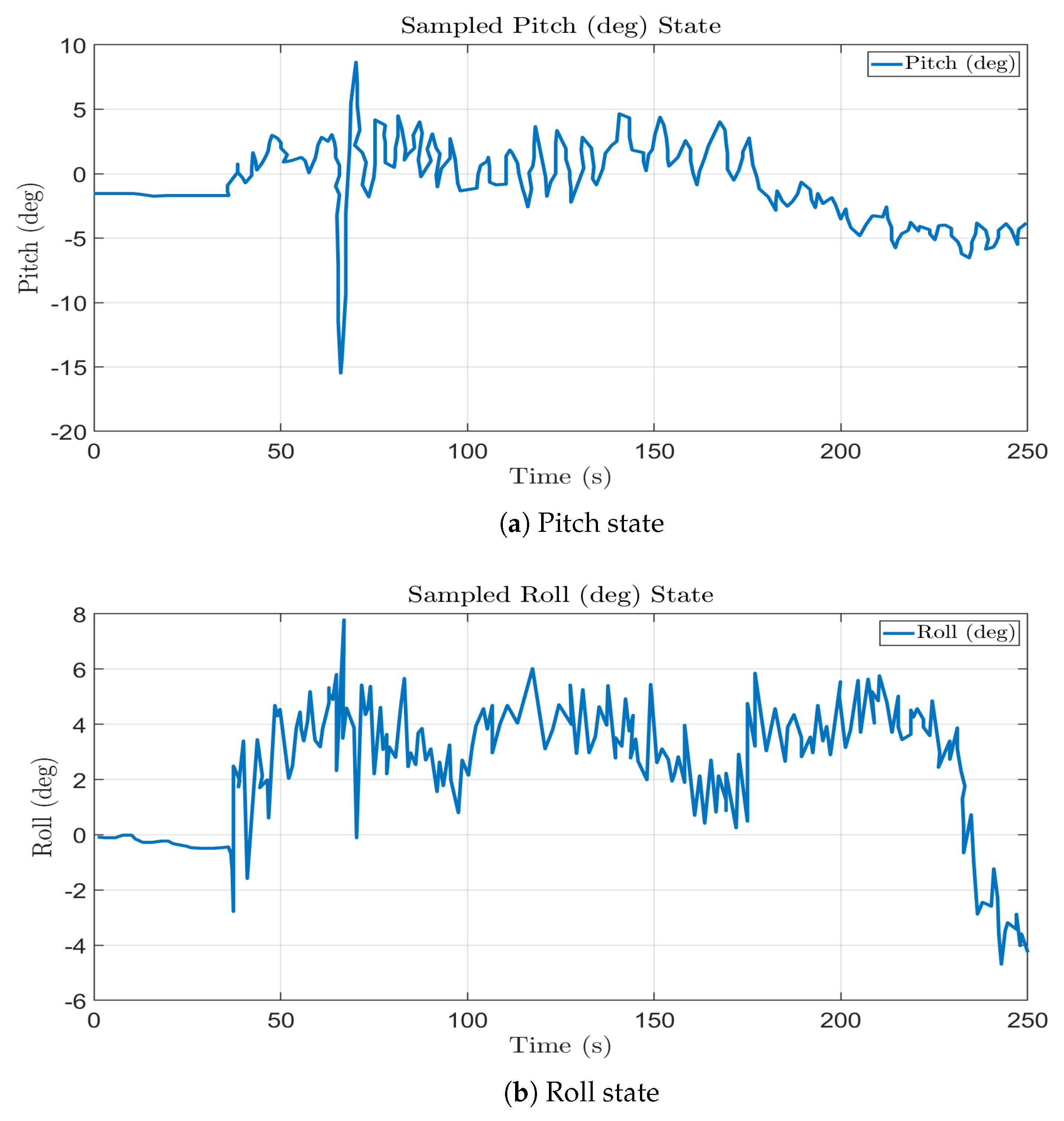

5.4. Pitch and Roll Behavior

Figure 24 illustrates the quadrotor’s pitch and roll responses during flight. The data reveal that both angles exhibit continuous fluctuations throughout the test, with frequent and pronounced deviations from the nominal zero-degree reference. These variations indicate that the quadrotor is actively and continuously adjusting its orientation to counteract external disturbances, primarily the variable wind gusts discussed earlier.

The high frequency and amplitude of these corrections often exceeding ±5° and occasionally reaching beyond ±10° reflect the responsiveness of the control system as it maintains flight stability. The plots demonstrate that the system remains highly dynamic, executing rapid adjustments to preserve trajectory accuracy despite persistent aerodynamic perturbations. Although the oscillations are relatively large, they remain well bounded and controlled through the implementation of auto-tuned PID parameters, underscoring the controller’s adaptability and robustness.

The corresponding attitude control parameters are summarized in

Table 8.

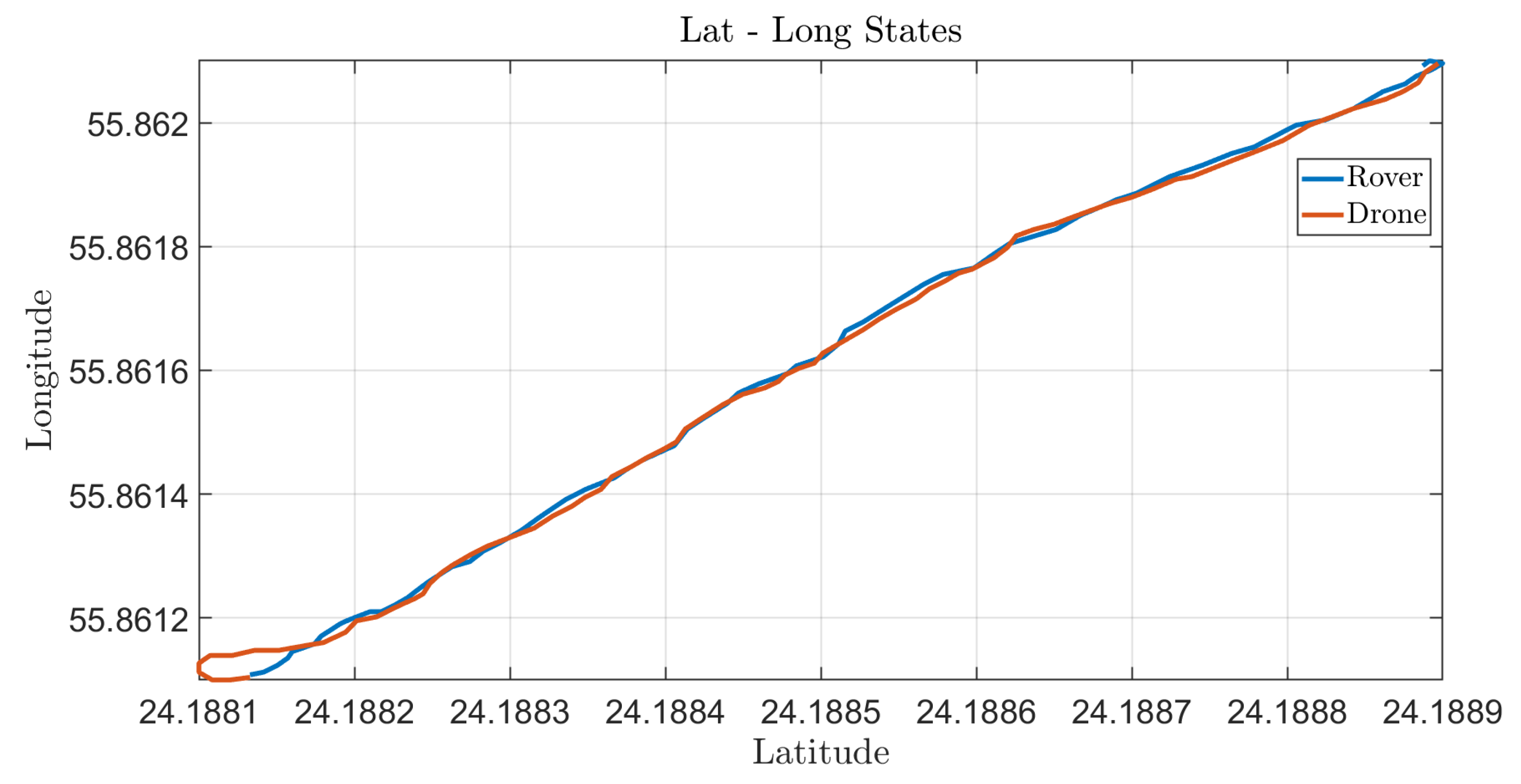

5.5. Geographic Coordinate Tracking

Figure 25 presents the geographic coordinate tracking performance of the quadrotor. The system achieved a mean positional error of 1.2 m, representing the average distance between the estimated and true coordinates, thereby indicating accurate localization. The 95% circular error probable (CEP) of 2.8 m further quantifies spatial precision, defining the radius within which the quadrotor’s estimated position is expected to lie 95% of the time.

An initial alignment delay of 4.1 s was recorded, corresponding to the time required for the GPS-based navigation system to achieve a stable and precise satellite lock. Collectively, these results confirm a robust and reliable positioning framework characterized by high spatial accuracy, predictable initialization behavior, and consistent performance during continuous flight operations.

5.6. Simulation and Experimental Correlation

To evaluate the fidelity of the proposed dynamic model, the key trajectory and attitude responses obtained from simulation were compared against those measured during real-world flight tests.

Table 9 presents representative metrics for

position tracking and yaw control. The comparison demonstrates that the simulated results closely align with experimental data, validating the dynamic model and controller tuning approach.

The results indicate strong agreement between simulation and experimental outcomes, with deviations below 10% for key translational and rotational parameters. Minor discrepancies are primarily attributed to aerodynamic disturbances, actuator saturation, and sensor latency effects not fully captured in the simulation model. Nevertheless, the close correspondence between the two datasets confirms the validity of the mathematical formulation and its suitability for controller design and performance prediction.

5.7. Statistical Robustness and Repeatability Analysis

To assess the consistency and reliability of the proposed control system, multiple flight trials were conducted under similar environmental conditions. Each experiment evaluated the system’s ability to track a moving ground target while maintaining stable attitude and altitude control. The resulting tracking and attitude errors were analyzed statistically across

independent trials.

Table 10 summarizes the key performance indicators, including the mean, standard deviation (SD), and

confidence interval (CI) for the primary flight variables.

The low standard deviations and narrow confidence intervals confirm the system’s strong repeatability across multiple runs. Variations between trials remained within of the mean values, indicating robust controller performance under minor environmental and aerodynamic fluctuations. The results further validate the reliability of the dynamic model and tuning approach used for the quadrotor’s real-time control system.

5.8. Comparative Evaluation with Existing Studies

To contextualize the proposed system’s performance,

Table 11 compares key tracking metrics against representative UAV tracking studies employing LQR, MPC, and adaptive PID approaches. Reported metrics were extracted directly from the corresponding publications and standardized where possible. It is important to note that the values originate from different UAV platforms, sensing modalities, flight trajectories, and environmental conditions; therefore, the table provides a qualitative cross-study context rather than a direct benchmark under identical conditions.

The comparison illustrates that the proposed delay-aware PID architecture performs within the typical range reported across prior UAV tracking studies. Because the referenced results were obtained under different experimental conditions, the table is intended only to position the achieved performance relative to the existing literature rather than to imply a controlled or fairness-matched benchmark.

The proposed architecture achieves tracking accuracy and transient performance comparable to those reported for more computationally intensive strategies such as MPC and 2-DOF PID, while maintaining significantly lower implementation complexity and real-time feasibility on embedded hardware. These characteristics make the approach particularly suitable for mission-critical applications prioritizing reliability and power efficiency.

7. Conclusions

This study presented the design, modeling, and experimental validation of a delay-aware hybrid PID control framework for real-time UAV-UGV cooperative tracking. By integrating classical PID regulation with Pixhawk’s estimator-based adaptive mechanisms (autotune, hover-throttle learning, and dynamic harmonic notch filtering) and explicit latency-compensation modeling, the proposed architecture achieved robust trajectory tracking with a mean positional error below one meter. Analytical validation using Padé-modeled delay representation and Routh–Hurwitz stability criteria confirmed closed-loop stability under communication delays, while field experiments demonstrated consistent performance across varying environmental conditions. Statistical robustness analysis further verified repeatability and reliability across multiple trials, emphasizing the framework’s real-world applicability.

The developed control system provides a practical, scalable, and computationally efficient solution for cooperative aerial–ground missions. Its ability to maintain stable flight and accurate target tracking under latency and disturbance effects highlights its suitability for autonomous inspection, environmental monitoring, and search-and-rescue applications. Compared with nonlinear MPC and 2-DOF PID controllers, the framework offers equivalent control precision with significantly lower computational cost, establishing a strong foundation for latency-resilient UAV deployments.

Future research will explore gain-scheduled PID strategies and enhanced estimator-based adaptive mechanisms, without employing machine learning control loops, as Pixhawk does not utilize ML for PID tuning. Additionally, integrating advanced sensor-fusion technique such as RTK-GPS, LiDAR, and visual–inertial odometry will further improve localization accuracy in GPS-denied environments. Extending the framework to multi-agent coordination and collaborative mission planning will broaden its applicability to large-scale cooperative aerial–ground robotic operations. Future work will also include systematic evaluation under extreme operating conditions, such as strong wind fields (5–8 m/s), GPS-denied navigation using visual–inertial odometry, and the tracking of high-speed moving targets (3–8 m/s). These experiments were not performed in the present study due to airspace and hardware safety constraints but constitute essential next steps for validating the system’s robustness in highly dynamic and mission-critical environments. In future extensions, learning-enhanced delay compensation or adaptive gain adjustment may also be explored as separate research directions. Although not part of the present framework, such approaches could provide an additional layer of autonomy and disturbance robustness in rapidly changing environments. Future work will also include controlled trials under stronger wind fields and higher target speeds to systematically characterize performance limits and extend the disturbance–response analysis presented here.