Abstract

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have revolutionized the automotive industry by leveraging data to perceive and interact with their environment effectively. Data safety is essential for supporting AV decision-making and ensuring reliability in complex environments. AVs continuously collect data from multiple sources like LiDAR, RADAR, cameras, and ultrasonic sensors to monitor road conditions, traffic signals, and pedestrian movements. An effective data classification framework is crucial for managing vast amounts of information and securing AV systems against cyber threats. This paper proposes a comprehensive framework for AV data classification, categorizing data by sensitivity, usage, and source. By integrating a review of the literature, real-world cases, and practical insights, this study introduces a novel data classification model and explores sensitivity criteria. The findings aim to assist industry stakeholders in creating secure, efficient, and sustainable AV ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Data, whether in the form of numbers, words, or images, represent a critical asset in any organizational context. Safeguarding the privacy and security of data is imperative, as attributes like accuracy, validity, relevance, completeness, accessibility, and consistency are vital for maintaining data integrity and usability [1]. Data classification, which involves categorizing data based on sensitivity levels throughout the data lifecycle, is central to determining appropriate security measures and evaluating the value of data as a business asset. Factors such as risk, disclosure, creation method, personal user data, and usage patterns guide this classification process [1].

In recent years, the integration of advanced technologies into the automotive industry has ushered in a new era of transportation, marked by the rise of autonomous vehicles (AVs). Data lie at the core of AV functionality, enabling these systems to perceive, interpret, and interact with their environments. Systematic data classification in the context of AVs organizes, categorizes, and labels diverse data types, forming the foundation for intelligent decision-making capabilities. Proper classification ensures AVs can navigate complex environments autonomously, securely, and efficiently, while addressing potential cyber threats that may compromise safety and reliability.

The rapid global adoption of AVs highlights the need for robust security measures to tackle emerging cyber security challenges. Studies predict a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19.56% in the U.S. AV market between 2023 and 2030, driven by technological advancements and consumer demand for innovative transportation solutions [2].

Given this backdrop, establishing a comprehensive framework for data classification in AV networks is a crucial step toward enhancing cybersecurity resilience. Proper classification of the diverse data transmitted and processed within AV environments serves as the first line of defense against such risks. This research aims to address these challenges by undertaking the following:

- i.

- Identifying diverse data types and sources within the AV environment to gain a comprehensive understanding of their role in AV operations.

- ii.

- Developing a framework for classifying these data types based on criteria such as sensitivity, relevance, criticality, and their potential impact on AV operations.

Through a thorough review of the existing literature and real-world cases, this study contributes to advancing autonomous driving technology while providing a foundation for cybersecurity professionals to develop robust defense measures to protect AV systems. By classifying multiple data types into well-defined sections, security personnel can focus their efforts on securing specific classified sections collectively, rather than devising individual security measures for each type of data. This approach streamlines the implementation of robust defenses, ensuring more efficient and effective protection of AV systems against evolving cyber threats.

This paper is structured to provide a comprehensive understanding of data classification in autonomous vehicles. A review of related works and the literature is first conducted in Section 2 to highlight existing research and identify gaps in data classification and cybersecurity within AV environments. The vulnerability landscape of AV systems is then analyzed in Section 3 by referencing real-world cyber-attack scenarios, emphasizing the critical need for enhanced data security. In Section 4, data types and sources in traditional vehicles are examined as a foundation, followed by an exploration of the data and sources unique to AV environments, including their functionalities and roles. Data flows within AVs are then analyzed in Section 5 to illustrate the essential role of data in enabling autonomous operations. In Section 6, we provide an overview of autonomous vehicle data flow. The proposed data classification framework for autonomous vehicles is described in Section 7, with data categorized based on sensitivity, usage, and sources to enhance security and operational efficiency. Finally, we provide the conclusions in Section 8.

2. Related Works

While a comprehensive data classification framework explicitly based on usage, sensor type, or sensitivity in autonomous vehicles (AVs) has yet to be fully established, significant strides have been made in related domains, offering valuable insights and foundational approaches.

Several pivotal studies have laid the groundwork for comprehending and subsequently refining the methods of data classification in AVs. In [3], the evolution of assistance systems into the current state of autonomous vehicles is explored. This study introduces a classification approach based on the degree of data sensitivity and presents a software design to assist manufacturers and administrators in addressing data protection challenges effectively.

The role of deep learning algorithms in data classification has also been extensively studied. For instance, Ref. [4] highlights the effectiveness of the YOLOV3 algorithm in improving image classification for AVs. The study emphasizes the importance of advanced deep learning techniques for accurate environmental image classification, which is essential for safe and efficient navigation. It also identifies challenges, such as the need for high computational power and optimized algorithms.

Further, research on machine learning for object classification has introduced methods for categorizing objects in AVs. In [5], a novel approach organizes datasets based on movement characteristics, enhancing accuracy in identifying vehicles and other objects. Similarly, Ref. [6] proposes a collaborative method for connected self-driving cars, using encryption and secure data-sharing techniques to preserve privacy while enabling seamless sensor data exchange for safe object recognition.

The management of personal data in AVs has also been a focal point of research. In [7], the authors emphasize the importance of protecting personal information in compliance with laws such as GDPR. This study outlines strategies for sorting and managing data while safeguarding individuals’ privacy, highlighting the critical balance between functionality and ethical data usage.

These studies collectively address various aspects of data classification and management, including algorithmic advancements, collaborative frameworks, and privacy considerations. Building on this foundational work, our research aims to address the gaps in establishing a comprehensive data classification framework for autonomous vehicles (AVs). While previous studies have provided significant insights into specific elements of data security, we adopted a holistic approach by leveraging an extensive array of academic papers and literary resources.

Data classification in autonomous vehicles (AVs) is an evolving field, focusing on data protection, object classification, and privacy preservation. Studies in the past have highlighted the use of advanced machine and deep learning techniques to enhance AV functionality and safeguard user privacy. Yet, a specific focus on the precise classification of data types within AV network environments, considering factors such as data sensitivity, remains uncharted territory. While the current body of research provides valuable insights into managing and utilizing data in AVs, it stops short of detailing a methodology for categorizing data based on sensitivity or other critical parameters. This research gap highlights the need for a comprehensive data classification framework that integrates data sensitivity, usage, and sensor-specific vulnerabilities.

Previous studies have offered a detailed understanding of various autonomous vehicle sensor functionalities and their use cases within autonomous vehicle environments. These studies provided a foundation for identifying the types of data generated by various sensors, including cameras, LiDAR, and radar systems [8,9,10,11]. Additionally, studies [12,13,14] contributed to a comprehensive understanding of the vehicular network ecosystem, encompassing Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V), Vehicle-to-Network (V2N), Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I), and Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communications. This knowledge is instrumental in systematically mapping data sources, a crucial step in developing a data classification framework.

To identify vulnerabilities and attack surfaces, we turned to research that explored real-world scenarios and threats. For instance, researchers highlighted specific attacks on forward-looking cameras, such as laser blinding and spoofing, which underscored the critical need to secure visual data against such disruptions [15,16]. Similarly, El Zorkany et al. in [13] revealed vulnerabilities in Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRCs) and IEEE 802.11p protocols, which could be exploited to disrupt traffic management systems. This study emphasized the importance of implementing authenticated and encrypted connections to protect against cyber attacks. Furthermore, the previous study examined Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I) communications, identifying risks like Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks, replay attacks, tampering, and Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks. These findings underscored the necessity of strong security measures to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of V2I data, which is essential for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSs) [17]. Previous research further detailed threats to V2X communication, such as message spoofing, Sybil attacks, and Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks, which could disseminate false information, disrupt traffic management systems, and compromise vehicle safety mechanisms [18].

Ibrahum et al. [19] categorized AV attack scenarios into environmental attacks, AV agent-based attacks, and environmental camouflage, using a safety taxonomy matrix to classify risks into Known/Safe, Known/Unsafe, Unknown/Unsafe, and Unknown/Safe areas. While the work focused on adversarial attacks and defenses, their categorical approach offered insights that guided the classification and categorization aspects of our data classification framework for AVs.

None of these past studies directly provided a concrete data classification framework; however, they offered essential insights. These included data sources, vulnerabilities, and attack vectors. These findings identified critical gaps, guiding the development of a robust framework that incorporates data origin, sensitivity levels, and usage patterns. By synthesizing this knowledge, our research proposes a comprehensive framework for data classification that addresses the unique needs of autonomous vehicles, ensuring secure and efficient operation.

3. Real-World Autonomous Vehicle Vulnerability Scenarios

Autonomous vehicles (AVs), which rely heavily on data-driven systems, are increasingly targeted by malicious cyber attacks. Understanding the scope and impact of these attacks on specific data types within AV environments is crucial for strengthening their security. In this section, we explore cyber threats targeting various data in AV environments and vulnerabilities that exist in AVs, drawing from recent instances of attacks along with attacks carried out by researchers in a simulated but real-world environment.

These real-world incidents in Table 1 vividly illustrate the vulnerability of every type of data within autonomous vehicles to cyber attacks, emphasizing the imperative of data classification as a fundamental defense. By systematically categorizing and organizing data according to importance and sensitivity, we establish a robust framework for preventing potential threats.

Table 1.

AV vulnerability breach real-world incidents.

4. Traditional Vehicle Environment Data and Sources

To understand the complexities of autonomous vehicle (AV) data, it helps to first look at the simpler data used in traditional vehicles. Traditional vehicles rely on basic datasets, providing a clear foundation for appreciating how much more advanced and intricate AV data have become. By comparing the two, we can see the enormous leap in data volume and complexity with AVs. This comparison highlights why precise data classification is essential to ensure robust cybersecurity in these advanced systems.

Table 2 outlines the various data types that traditional vehicles handle, showcasing the broad and specific information essential for their operation. Yet, the leap into self-driving car technology has significantly expanded the landscape of vehicle data. In the upcoming section, this study showcases how autonomous vehicles have introduced a whole new set of data complexities, stepping beyond the foundational data discussed here.

Table 2.

Different data types along with their sources in traditional vehicles.

5. Autonomous Vehicle Environment Data and Sources

Recognizing the diverse array of data sources and their associated security risks is crucial for safeguarding autonomous vehicles (AVs) against cyber threats. In this section, we identify multiple data sources, examine the corresponding data they produce, and analyze their roles in autonomous vehicle (AV) operation, highlighting their critical importance in ensuring smooth and secure functioning within AV networks.

5.1. Sensors

Sensors are the eyes and ears of self-driving cars, crucial for helping these vehicles understand and move through the world safely.

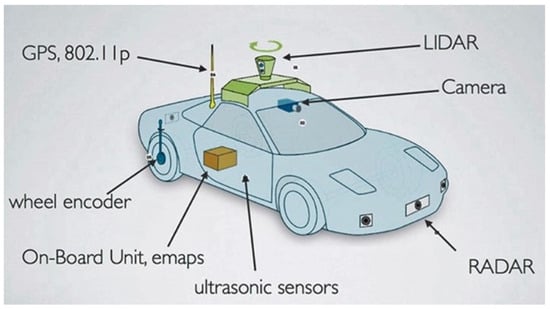

The sensors shown in Figure 1 collect a huge amount of information from all around the car, including the distance to nearby objects and the speed of surrounding vehicles. These data are highly varied, providing the car with everything it needs to navigate roads, avoid accidents, and interact smoothly with its environment. Each sensor has a specific role, gathering the particular types of data needed for the car to make smart decisions quickly, as depicted in Table 3 below.

Figure 1.

Primary sensors’ integration in autonomous vehicle systems [28]. In the figure, LIDAR represents Light Detection and Ranging, GPS represents Global Positioning System, and RADAR represents Radio Detection and Ranging.

Table 3.

Types of sensors and data produced.

5.2. GPS

GPS in autonomous vehicles (AVs) is a sophisticated component that harnesses satellite signals to deliver comprehensive spatial data, as shown in Table 4, which is crucial for the vehicle’s navigation and decision-making processes. By triangulating signals from multiple satellites, the GPS sensor accurately determines the vehicle’s geographical location, elevation, direction, and speed. This process enables AVs to understand their position within a global context, crucial for mapping routes, adapting to changes in the environment, and ensuring accurate travel paths without the need for constantly updated physical maps [29].

Table 4.

GPS data in AVs.

5.3. Diagnostic Data

Diagnostic data, as shown in Table 5, encompass information that reveals details about the vehicle’s functional state, condition, and any issues that might influence its efficiency or security. This information mainly originates from the vehicle’s onboard diagnostics (OBD) system, which is responsible for tracking diverse aspects and systems of the vehicle, such as the engine, transmission, electronics, and other essential parts.

Table 5.

Diagnostic data in AVs.

5.4. User Input Data

The data input by occupants in autonomous vehicles (AVs) encompasses any information directly provided or communicated by them. This includes various interactions like preferences, adjustments to settings, manual inputs, and voice commands. Such inputs are vital for tailoring the driving experience, ensuring comfort, and, in certain situations, overriding autonomous functions for safety or preference purposes. Table 6 presents various types of user input data along with their sources, functionality, and examples.

Table 6.

User input data in AVs.

5.5. Connectivity Data

Connectivity data play a pivotal role in enhancing intelligent vehicle operations and interactions within the broader transportation ecosystem. These types of data, as shown in Table 7, enable communication between autonomous vehicles and various external entities, including other vehicles, infrastructure, networks, and pedestrians.

Table 7.

Connectivity data in AVs.

All different V2 (Vehicle-to-Vehicle, Vehicle-to-Infrastructure, Vehicle-to-Network, etc.) systems have unique security threats; however, V2X technology addresses all of these challenges under a unified communication framework. As AV connectivity plays a pivotal role in the current transportation ecosystem, understanding the security threats associated with V2X technology is crucial for ensuring its safe and effective implementation. The primary security challenges for V2X include managing dynamic network topology, ensuring network scalability, addressing heterogeneity across global infrastructures, minimizing communication latency, prioritizing critical data, adapting to future platforms, preventing attacks on both users and systems, and maintaining user trust and privacy through advanced solutions like PKI, pseudonymization, and hybrid techniques [18].

6. Autonomous Vehicle Data Flow Overview

Before classifying data in autonomous vehicles (AVs), it is essential to understand how data flow through their core systems, i.e., Perception, Planning, Control, and Communication. This section shows how the integration of sensors, algorithms, and communication protocols enables AVs to interpret their environment, make decisions, and execute actions. Understanding this data flow establishes the foundation for exploring how data classification enhances security, protects sensitive information, and ensures reliable system performance.

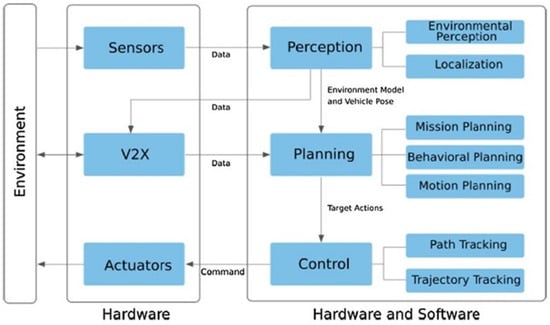

Figure 2 depicts a typical layout of an autonomous vehicle system, highlighting key functions crucial for its operation. The Perception layer gathers data and interprets relevant information from the vehicle’s surroundings using sensors and V2X messages. It includes two parts: environmental perception and localization. Environmental perception identifies and categorizes surrounding objects like obstacles, road geometry, and signs using methods like Multi-Object Tracking and segmentation, with sensors such as LIDARs, cameras, and radars. Localization, or SLAM, builds and updates a map while tracking the vehicle’s position and orientation.

Figure 2.

A typical AV system overview [30].

The Planning layer generates optimal paths and actions based on Perception’s data. It employs decision-making algorithms to navigate the vehicle safely and efficiently.

The Control layer executes the planned trajectories by controlling the vehicle’s actuators, ensuring it follows the desired path accurately.

Lastly, the Communication layer enables information exchange between autonomous vehicles and infrastructure, fostering cooperative behavior and enhancing traffic efficiency. This structured framework enables autonomous vehicles to perceive, plan, control, and communicate effectively, ensuring safe and reliable driving in diverse scenarios.

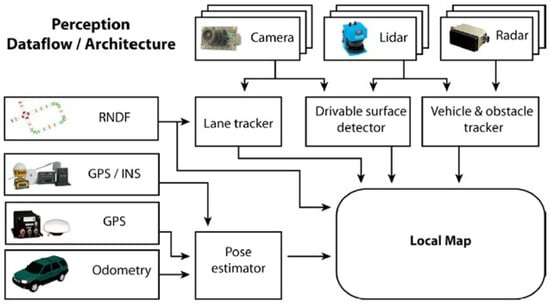

Figure 3 illustrates a multi-layered method through which an autonomous vehicle understands its environment. It begins with the collection of data via a variety of sensors, as presented in Figure 1. These sensors collect visual, spatial, and motion-related information, while the Road Network Definition File (RNDF) offers predefined routes for navigation. The collected data are then processed by specialized units: cameras identify road lanes, LiDAR delineates drivable areas, and radar monitors the velocity and position of nearby objects. Combined with accurate location data from GPS/INS and odometry, this information is processed by the pose estimator, which integrates the data to determine the vehicle’s exact location and direction. Based on this integration, a local map is continuously updated, which the vehicle utilizes for navigation.

Figure 3.

Information integration in the Perception framework [31].

Regardless of how data traverses through the system, incorporating data classification at each stage is essential for maximizing security and operational efficiency. At the Perception stage, the immediate classification of incoming data by sensitivity is crucial. For instance, data from GPS and cameras should be considered highly sensitive, necessitating stringent encryption and access controls. As these data progress to the Planning and Control stages, their classification guides how they are processed and safeguarded, ensuring that critical data impacting vehicle functions remain protected. In the Communication stage, correct data classification is key to facilitating safe and secure communication with other systems like V2V and V2I, thereby preserving data integrity and confidentiality, which are vital for the reliable operation of AVs. Embedding data classification into the data flow process underscores the significance of robust data management for the effective and safe functionality of autonomous vehicles.

7. Data Classification Frameworks of Autonomous Vehicles

7.1. Based on Sensitivity

Classifying data based on sensitivity is crucial for determining the appropriate level of security and access controls. Sensitivity classification helps in prioritizing the protection of data according to its importance and potential impact on privacy, security, and operational integrity. The primary bases for classifying data according to its sensitivity include public, sensitive, highly sensitive, and critical data. This framework categorizes data by evaluating its purpose, usage, and the potential risks associated with exposure.

7.1.1. Public Data

This category comprises data that can be freely shared without significant privacy or security concerns. Public data in the framework encompass generic, non-identifiable information such as broad traffic patterns, environmental models, and aggregated usage statistics, which pose minimal privacy risks [32].

7.1.2. Sensitive Data

Data and information falling under this category could potentially compromise user privacy or reveal operational details if exposed. Sensitive data encompass data that can indirectly reveal user habits or geographic trends, such as identifiable landmarks, location-based data, and specific diagnostic alerts [33].

7.1.3. Highly Sensitive Data

This classification involves data with a substantial risk of privacy violation or operational interference if improperly disclosed. High-sensitivity data encompass directly identifiable information and data in the framework, such as license plates, advanced vehicle stability data, and health diagnostics, which can pose privacy or security risks if misused.

7.1.4. Critical Data

Representing the most sensitive category, critical data include information directly impacting personal safety, operational integrity, and security. Unauthorized access to this data could lead to severe privacy breaches, safety risks, and security vulnerabilities. Critical data encompass data such as personal, secure, or safety-critical information, including biometric identifiers, precise geolocations, and vehicle operational faults that, if compromised, could lead to severe harm [34].

The classification process evaluated every type of data collected by the sensors against these four categories, considering the functional purpose and potential risks associated with exposure. Each data type from every sensor was assessed for its intended application and potential impact if compromised, adhering to a validation process informed by scientific studies and regulatory guidelines. The validation process relied on published studies such as [32], which confirmed the minimal privacy implications of public data. Sensitive data classifications were grounded in research exploring the privacy risks of location-based and contextual data [33]. High-sensitivity data validation relied on studies highlighting the risks of identifiable data such as license plates or vehicle stability metrics [35]. Critical data classifications were supported by findings on the security and privacy challenges posed by personal and safety-critical data under regulations such as GDPR [34].

The novel classification table developed using this framework maps each sensor’s specific data types to these sensitivity levels, ensuring a use-case and importance-based process. This framework, grounded in the scientific literature and regulatory guidelines, establishes a robust foundation for managing data sensitivity in AV systems, enabling developers to implement targeted and effective data protection measures.

Classifying data based on sensitivity (Table 8) is indispensable in the current autonomous vehicle (AV) scenario for several compelling reasons. In the complex ecosystem of AVs, where vast amounts of data are constantly being collected, processed, and shared, the stakes for data security and privacy are exceptionally high. Sensitivity data classification enables stakeholders to implement a layered security approach, ensuring that the most critical data—be it related to vehicle operation, personal user information, or safety mechanisms—receives the highest level of protection. This helps in pinpointing which data require stringent encryption, who should have access to these data, and what kind of breach detection mechanisms are necessary.

Table 8.

Sensitivity-based classification framework.

Moreover, in the event of a cyber attack, a clear understanding of data sensitivity allows for a rapid assessment of potential impacts, prioritization of responses, and effective mitigation of damage. Sensitivity classification not only safeguards the integrity and functionality of AV systems against malicious exploits, but also upholds the trust and confidence of users by protecting their privacy. In an era where data breaches can have dire consequences, ranging from personal privacy violations to life-threatening safety risks, the meticulous classification of data based on sensitivity is not just a security measure, it is a fundamental pillar supporting the safe advancement of autonomous vehicle technology.

7.2. Based on Usage

This study classifies autonomous vehicle (AV) data by its usage—into operational, analytical, and regulatory categories.

7.2.1. Operational Usage

Operational data are directly involved in the real-time operation and oversight of autonomous vehicles (AV).

7.2.2. Analytical Usage

Analytical data focuses on enhancing AV systems, optimizing vehicle performance, and improving user interactions. It involves incorporating machine learning models to refine decision-making, leveraging usage data to anticipate maintenance needs, and fostering continuous advancements in AV technology.

7.2.3. Regulatory Usage

This classification encompasses data essential for meeting legal and regulatory obligations, including incident logging for investigation, safeguarding user data, and adhering to traffic regulations, emphasizing the vital role of identifying and overseeing regulatory data to ensure alignment with legal mandates and safeguard the interests of both users and the broader community.

Having delineated the three principal usage categories—operational, analytical, and regulatory—we established a systematic approach to classify each autonomous vehicle (AV) data type. This approach is anchored in functional role analysis, which examines the purpose and timeframe in which each data source is utilized (i.e., immediate operation, long-term system improvements, or legal compliance). Building on the data sources identified in Section 5 of this paper, we mapped these sources and their respective data to the three usage categories by scrutinizing their real-world functions.

- Data essential for real-time control or critical to immediate vehicle operation are designated as operational data.

- Information primarily used for post-processing or long-term improvements is designated as analytical data.

- Datasets necessitated by legal, safety, or compliance requirements are deemed regulatory data.

After completing the initial mapping of data to the three usage categories, a literature review was undertaken to validate the role (primary usage) and urgency of each data source. This review confirmed whether the data in question were critical for immediate operational decisions, instrumental for post-processing and long-term analytical insights, or mandated by regulatory frameworks for compliance and legal accountability. Following the methodology described above, each data source was scrutinized based on the following:

- i.

- Immediate Impact on Vehicle Behavior: Data that inform instantaneous control decisions, such as sensor data for collision avoidance, were classified under operational usage.

- ii.

- Long-Term Insight Generation: Data used for offline machine learning, performance analysis, or predictive maintenance, such as aggregated sensor logs, were categorized as analytical.

- iii.

- Legal and Compliance Obligations: Data required for incident reporting, privacy compliance, emissions checks, or insurance documentation, such as event data recorders and audit logs, were classified under regulatory usage.

Classifying AV data based on use, as in Table 9, helps identify what data need the most protection. By understanding whether data are used for operating the vehicle, for analysis, or to comply with laws, risks can be better managed. This classification guides us in applying the right security measures to the right data, ensuring sensitive information is safeguarded and reducing the chances of cyber threats.

Table 9.

Usage-based classification framework.

7.3. Based on the Overall Sensitivity of the Data Source

In the ongoing development of autonomous vehicle (AV) technologies, precise management and understanding of the collected data are imperative. A systematic classification of data based on its sensitivity is essential for preventing privacy infringements and mitigating cybersecurity threats. By categorizing data into four distinct levels, i.e., public, sensitive, highly sensitive, and critical, appropriate security measures can be tailored to each level. This stratification not only optimizes the allocation of security resources, but also ensures that the confidentiality and integrity of the data are preserved according to the data’s relative importance and the severity of potential risks.

To devise this classification, we conducted a comprehensive review of the existing literature on attack vectors in AV systems, examining both specific points of vulnerability and the consequences of potential breaches. By analyzing past incidents and theoretical threats discussed in academic and industry research, we identified how each data source could be exploited and the extent of potential harm. The analysis considered the nature of the attack, the attack surface vector, and how attacks on it affect AV systems, including whether the result halts the system, threatens life, breaches privacy, or causes simple inconvenience. Drawing upon these findings, we categorized the data sources into four key tiers of sensitivity. Each tier reflects both the likelihood of an attack and the degree of potential damage—ranging from the exposure of operational details to critical risks that could compromise vehicle safety or result in significant privacy violations.

In Table 10, we have categorized the primary data sources for AVs as detailed in Section 5, assigning each to the most appropriate sensitivity category. While acknowledging that some data sources may generate information at various sensitivity levels, this classification primarily focuses on the highest level of risk associated with the data if it were compromised. This methodical approach aids in prioritizing security efforts and safeguarding sensitive information effectively.

Table 10.

Source-based classification framework.

Every data source identified and tabulated in Table 10 is essential for the operation and functionality of autonomous vehicles (AVs), and classifying these sources based on their sensitivity is crucial for implementing the right security measures.

The proposed framework not only establishes a foundation for developing new security measures, but also enhances the adaptability of existing systems by addressing inter-disciplinary challenges in autonomous vehicle safety. For instance, Auto-CIDS, developed by Sorkhpour et al. [60], employs Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and unsupervised algorithms to autonomously detect threats like Denial-of-Service (DoS), fuzzy, and spoofing attacks. Similarly, Anthony et al. [61] developed a high-accuracy IDS for autonomous vehicles using non-tree-based machine learning techniques, achieving up to 99% accuracy on real-world datasets to address threats like Denial-of-Service and spoofing attacks. While these studies focused on intrusion detection, their work aligns with our proposed data classification framework. Integrating a robust data classification framework could further enhance the ability to prioritize critical data, optimize resource allocation, and strengthen real-time threat detection in dynamic vehicular networks.

Koopman and Wagner [62] highlight the complexity of ensuring AV safety due to the need to validate adaptive systems and manage cross-disciplinary safety concerns, such as resilience in unstructured environments and fail-over mission planning. Incorporating this data classification framework into these safety measures can further refine such systems by enabling the prioritization of critical data, thereby optimizing response strategies and fortifying real-time decision-making against dynamic cybersecurity threats.

This systematic method improves the cybersecurity stance of AV systems and helps stakeholders focus their security efforts, ensuring that the most sensitive data are protected with the most robust measures to effectively reduce potential risks. Such classifications lay the groundwork for a robust security framework that supports the dependable and secure functioning of autonomous vehicles.

8. Conclusions

Data classification in AVs is required as a foundational step toward achieving a harmonious balance between innovation and security. It serves as a critical mechanism for identifying and prioritizing data according to its sensitivity and usage, ensuring that the most critical information is accorded the highest level of protection. This classification process is instrumental in mitigating the risks associated with data breaches, cyber attacks, and unintended privacy violations. By establishing clear demarcations between different types of data, stakeholders can implement customized security measures, comply with regulatory requirements, and foster public trust in AV technology.

In this study, we proposed a novel data classification framework designed to categorize AV data into meaningful brackets, such as public, sensitive, highly sensitive, and critical data. The introduced data classification framework, which categorizes AV data into public, sensitive, highly sensitive, and critical brackets based on sensitivity, usage, and source, is the key result of this study. Categorizing data on different bases is vital as AVs become more integrated into our daily lives, carrying an ever-increasing load of sensitive information. This ensures that every piece of information is treated with the highest regard based on its importance and vulnerability. Also, instead of treating every single piece of data individually and creating separate security measures for each, this classification framework groups similar types of data into a singular bracket. This approach simplifies the development of security measures by enabling a group rather than individualistic treatment of data, enhancing both efficiency and practicality. By focusing efforts on the most sensitive and vulnerable data categories, this framework provides a structured pathway for mitigating the risks associated with data breaches, cyber attacks, and privacy violations.

Looking ahead, there are several opportunities to expand upon this foundational framework to address emerging challenges and evolving technologies. Validation through simulations and real-world applications is a crucial next step. Applying the framework in realistic AV environments using testbeds or simulation platforms will help assess its practical effectiveness and robustness. Analyzing past cybersecurity incidents, such as the Tesla and Jeep attacks, can provide a tangible basis for evaluating its ability to address specific vulnerabilities. Additionally, quantitative assessments through simulation-based testing can offer critical insights, strengthening the framework’s applicability and showcasing its potential in mitigating security risks across AV systems.

The integration of machine learning and emerging technologies offers promising avenues for further development. Machine learning algorithms can dynamically classify data, enabling real-time adaptability to evolving threats and operational contexts in complex AV ecosystems. Such integration would enhance scalability and ensure the framework remains robust in addressing new challenges. Similarly, as technologies like 5G networks and quantum-resistant cryptography gain prominence, the framework must evolve to accommodate their unique security implications. Research in this area will ensure the framework remains forward-looking, aligning with the technological advancements shaping next-generation AV systems.

By addressing these future directions, this framework can evolve into a comprehensive solution capable of safeguarding privacy, enhancing vehicle reliability, and fostering trust in autonomous technologies, paving the way for a secure and connected future. This framework is a step toward that vision: a world where technology moves us forward with confidence to data security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S.; Data curation, S.R.N.; Methodology, S.R.N.; Project administration, W.S.; Supervision, W.S.; Validation, S.R.N.; Visualization, S.R.N.; Writing—original draft, S.R.N.; Writing—review and editing, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shaikh, R.; Sasikumar, M. Data classification for achieving security in cloud computing. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 45, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Autonomous Vehicles Market Report 2024–2030: Level 3 Self-Driving Cars Spearhead Growth in Autonomous Transport Sector. Research and Markets. 2024. Available online: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/united-states-autonomous-vehicles-market-090400211.html?guccounter=1 (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Vaniš, M.; Zelinka, T.; Ščerba, T.; Stárková, A. Classification of non-personal data in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 Smart City Symposium Prague (SCSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 26–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, P.; Dhanavel, K.; Deepak, K.; Dhinakaran, R. Autonomous Vehicle Image Classification using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS), Erode, India, 23–25 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alqarqaz, M.; Bani Younes, M.; Qaddoura, R. An Object Classification Approach for Autonomous Vehicles Using Machine Learning Techniques. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Bi, R.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, D. Toward lightweight, privacy-preserving cooperative object classification for connected autonomous vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 2787–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlada, M.; Holý, R.; Jirovský, J.; Kasalický, T. Protection of personal data in autonomous vehicles and its data categorization. In Proceedings of the 2022 Smart City Symposium Prague (SCSP), Prague, Czech Republic, 26–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatious, H.A.; Khan, M. An overview of sensors in Autonomous Vehicles. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 198, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.Z.; Boone, R.G. Overview of autonomous vehicle sensors and systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Operations Excellence and Service Engineering, Orlando, FL, USA, 10–11 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.; O’Mahony, N.; Krpalcova, L.; Riordan, D.; Walsh, J.; Murphy, A.; Ryan, C. Sensor technology in autonomous vehicles: A review. In Proceedings of the 2018 29th Irish Signals and Systems Conference (ISSC), Belfast, UK, 21–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miethig, B.; Liu, A.; Habibi, S.; Mohrenschildt, M.v. Leveraging thermal imaging for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Michigan, USA, 19–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano Dominguez, J.M.; Mateo Sanguino, T.J. Review on v2x, i2x, and p2x communications and their applications: A comprehensive analysis over time. Sensors 2019, 19, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zorkany, M.; Yasser, A.; Galal, A.I. Vehicle to vehicle “V2V” communication: Scope, importance, challenges, research directions and future. Open Transp. J. 2020, 14, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, M.N.; Ahmed, Q.Z.; Khan, F.A.; Hafeez, M. A survey of autonomous vehicles: Enabling communication technologies and challenges. Sensors 2021, 21, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boloor, A.; Garimella, K.; He, X.; Gill, C.; Vorobeychik, Y.; Zhang, X. Attacking vision-based perception in end-to-end autonomous driving models. J. Syst. Archit. 2020, 110, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Xu, W.; Liu, J. Can you trust autonomous vehicles: Contactless attacks against sensors of self-driving vehicle. Def Con 2016, 24, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Marcillo, P.; Tamayo-Urgilés, D.; Valdivieso Caraguay, Á.L.; Hernández-Álvarez, M. Security in V2I communications: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosal, A.; Conti, M. Security issues and challenges in V2X: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2020, 169, 107093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahum, A.D.M.; Hussain, M.; Hong, J.-E. Deep learning adversarial attacks and defenses in autonomous vehicles: A systematic literature review from a safety perspective. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, G. A 19-Year-Old Security Researcher Describes How He Remotely Hacked into over 25 Teslas. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/teen-security-researcher-describes-how-he-hacked-into-25-teslas-2022-1 (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Werling, C.; Kühnapfel, N.; Jacob, H.N.; Drokin, O. Jailbreaking an Electric Vehicle in 2023 or What It Means to Hotwire Tesla’s x86-Based Seat Heater. 2023. Available online: https://www.blackhat.com/us-23/briefings/schedule/#jailbreaking-an-electric-vehicle-in--or-what-it-means-to-hotwire-teslas-x-based-seat-heater-33049 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Erwin, B. The Groundbreaking 2015 Jeep Hack Changed Automotive Cybersecurity. Available online: https://fractionalciso.com/the-groundbreaking-2015-jeep-hack-changed-automotive-cybersecurity/#:~:text=The%20two%20hackers%2C%20Charlie%20Miller,control%2C%20including%20steering%20and%20braking (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Golson, J. Car Hackers Demonstrate Wireless Attack on Tesla Model S. 2016. Available online: https://www.theverge.com/2016/9/19/12985120/tesla-model-s-hack-vulnerability-keen-labs (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Williams, M. BMW Cars Found Vulnerable in Connected Drive Hack. 2015. Available online: https://www.pcworld.com/article/431610/bmw-cars-found-vulnerable-in-connected-drive-hack.html (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Mit, R. Two Years Since the Tesla GPS Hack. 2021. Available online: https://www.gpsworld.com/two-years-since-the-tesla-gps-hack/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Hunt, T. Controlling Vehicle Features of Nissan LEAFs Across the Globe via Vulnerable APIs. 2016. Available online: https://www.troyhunt.com/controlling-vehicle-features-of-nissan/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Greenberg, A. A New Wireless Hack Can Unlock 100 Million Volkswagens. Security. 2018. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2016/08/oh-good-new-hack-can-unlock-100-million-volkswagens/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Hristozov, A. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Autonomous Vehicles. 2020. Available online: https://www.embedded.com/the-role-of-artificial-intelligence-in-autonomous-vehicles/ (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Zein, Y.; Darwiche, M.; Mokhiamar, O. GPS tracking system for autonomous vehicles. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 3127–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braud, T.; Ivanchev, J.; Deboeser, C.; Knoll, A.; Eckhoff, D.; Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, A. AVDM: A hierarchical command-and-control system architecture for cooperative autonomous vehicles in highways scenario using microscopic simulations. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2021, 35, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Carballo, A.; Yang, H.; Takeda, K. Perception and sensing for autonomous vehicles under adverse weather conditions: A survey. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 196, 146–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, F.M.; Sammarco, M.; Costa, L.H.M.; Detyniecki, M. Vehicle telematics via exteroceptive sensors: A survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.12632. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W. Sensors for autonomous vehicles. In Handbook of Power Electronics in Autonomous and Electric Vehicles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yeong, D.J.; Velasco-Hernandez, G.; Barry, J.; Walsh, J. Sensor and sensor fusion technology in autonomous vehicles: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyad, J.; Jaradat, M.A.; Gruyer, D.; Najjaran, H. Deep learning sensor fusion for autonomous vehicle perception and localization: A review. Sensors 2020, 20, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Hu, H.; Liang, Y.; Shen, G. On the application of cameras used in autonomous vehicles. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 4319–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.A.; Shariff, W.; O’callaghan, D.; Merla, A.; Corcoran, P. On the role of thermal imaging in automotive applications: A critical review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 25152–25173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.S.; Keoh, S.L.; Thing, V.L. Autonomous vehicle ultrasonic sensor vulnerability and impact assessment. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 4th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Singapore, 5–8 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shoukry, Y.; Martin, P.; Tabuada, P.; Srivastava, M. Non-invasive spoofing attacks for anti-lock braking systems. In Proceedings of the Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems-CHES 2013: 15th International Workshop, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 20–23 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prikhodko, I.P.; Bearss, B.; Merritt, C.; Bergeron, J.; Blackmer, C. Towards self-navigating cars using MEMS IMU: Challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Inertial Sensors and Systems (INERTIAL), Lake Como, Italy, 26–29 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, R.; Bevly, D.M. The use of GPS for vehicle stability control systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2004, 51, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Nandal, R. A framework on driving behavior and pattern using On-Board diagnostics (OBD-II) tool. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 3762–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, M.; Janjua, H.; Thangarajan, A.S.; Crispo, B. and Hughes, D. Securing the On-Board Diagnostics Port (OBD-II) in Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Transp. Cybersecur. Priv. 2020, 2, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Aras, V.P. Design of Electronic Control Unit (ECU) for Automobiles-Electronic Engine Management System. Master’s Thesis, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.; Meng, S.; Wüthrich, M.V. What can we learn from telematics car driving data: A survey. Insur. Math. Econ. 2022, 104, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, L. The Future of Driving: How Voice AI is Revolutionizing the In-Car Experience. Available online: https://www.kardome.com/blog-posts/voice-ai-revolutionizing-car-experience (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Smruthi, K.; Yashwanth, K.; Vijayalakshmi, M. Intelligent autonomous vehicle control using smartphone. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. Infrared sensors for autonomous vehicles. Recent Dev. Optoelectron. Devices 2018, 29, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Leiss, P. The Functional Components of Autonomous Vehicles. 2018. Available online: https://www.robsonforensic.com/articles/autonomous-vehicles-sensors-expert (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Lisseman, J.; Diwischek, L.; Essers, S.; Andrews, D. In-Vehicle Touchscreen Concepts Revisited: Approaches and Possibilities. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars-Electron. Electr. Syst. 2014, 7, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Privacy Implications of Autonomous Vehicles. Data Protection Report 2017. Available online: https://www.dataprotectionreport.com/2017/07/the-privacy-implications-of-autonomous-vehicles/#:~:text=Autonomous%20vehicles%20may%20collect%20and,a%20high%20degree%20of%20certainty (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Iqbal, A.; Ahmed, S.S.; Tauqeer, M.D.; Sultan, A.; Abbas, S.Y. Design of multifunctional autonomous car using ultrasonic and infrared sensors. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Wireless Systems and Networks (ISWSN), Lahore, Pakistan, 19–22 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guesmi, A.; Hanif, M.A.; Ouni, B.; Shafique, M. Physical adversarial attacks for camera-based smart systems: Current trends, categorization, applications, research challenges, and future outlook. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 109617–109668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alheeti, K.M.A.; Al-Zaidi, R.; Woods, J.; McDonald-Maier, K. An intrusion detection scheme for driverless vehicles based gyroscope sensor profiling. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 8–10 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- El-Rewini, Z.; Sadatsharan, K.; Sugunaraj, N.; Selvaraj, D.F.; Plathottam, S.J.; Ranganathan, P. Cybersecurity attacks in vehicular sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 13752–13767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Chen, Q.A.; Lin, Z. Plug-N-Pwned: Comprehensive vulnerability analysis of {OBD-II} dongles as a new {Over-the-Air} attack surface in automotive IoT. In Proceedings of the 29th USENIX security symposium (USENIX Security 20), Boston, MA, USA, 12–14 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Qin, Z.; Lin, X.; Hu, S.; Wang, Q.; Ren, K. Hidden voice commands: Attacks and defenses on the VCS of autonomous driving cars. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Valasek, C. A Survey of Remote Automotive Attack Surfaces; IOActive: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, W.; Shi, Y. In-vehicle network attacks and countermeasures: Challenges and future directions. IEEE Netw. 2017, 31, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkhpour, M.; Yazdinejad, A.; Dehghantanha, A. Auto-CIDS: An Autonomous Intrusion Detection System for Vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Autonomous Cybersecurity, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 14–18 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, C.; Elgenaidi, W.; Rao, M. Intrusion detection system for autonomous vehicles using non-tree based machine learning algorithms. Electronics 2024, 13, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, P.; Wagner, M. Autonomous vehicle safety: An interdisciplinary challenge. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2017, 9, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).