A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Blood Spot per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Adolescents in Chitwan Valley, Nepal

Abstract

1. Introduction

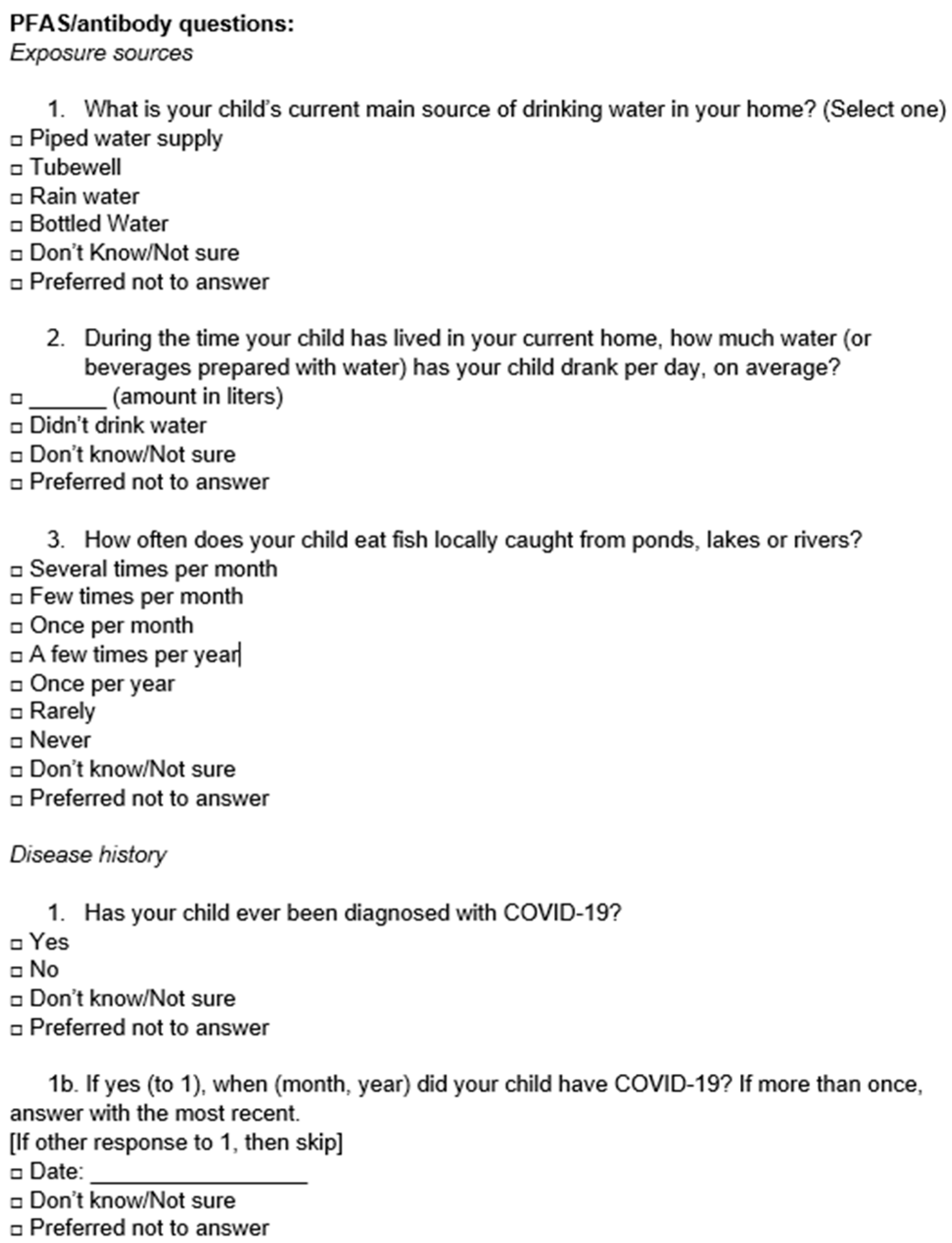

2. Materials and Methods

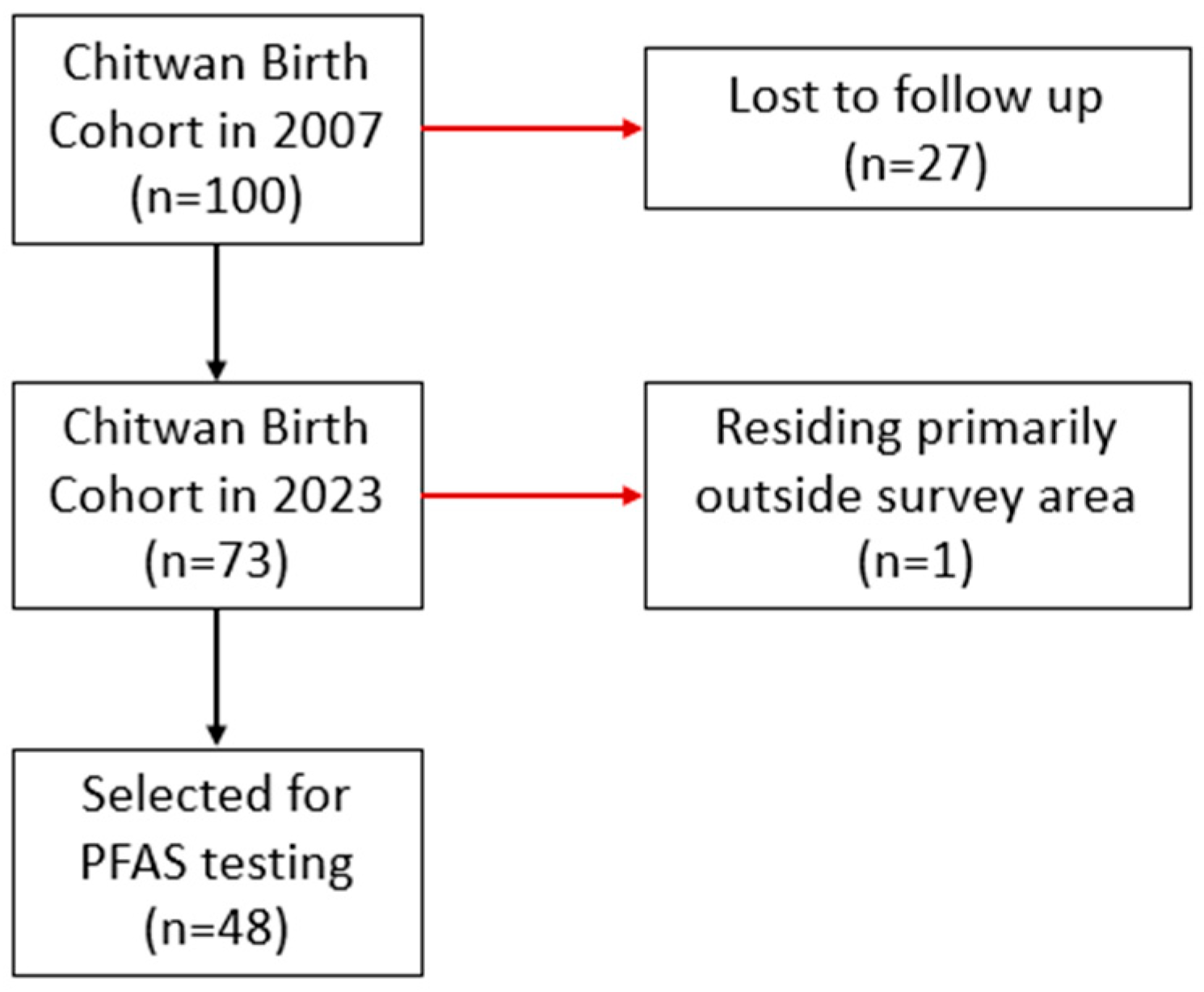

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

2.2. Dried Blood Spot (DBS) Sample Collection

2.3. PFAS Testing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

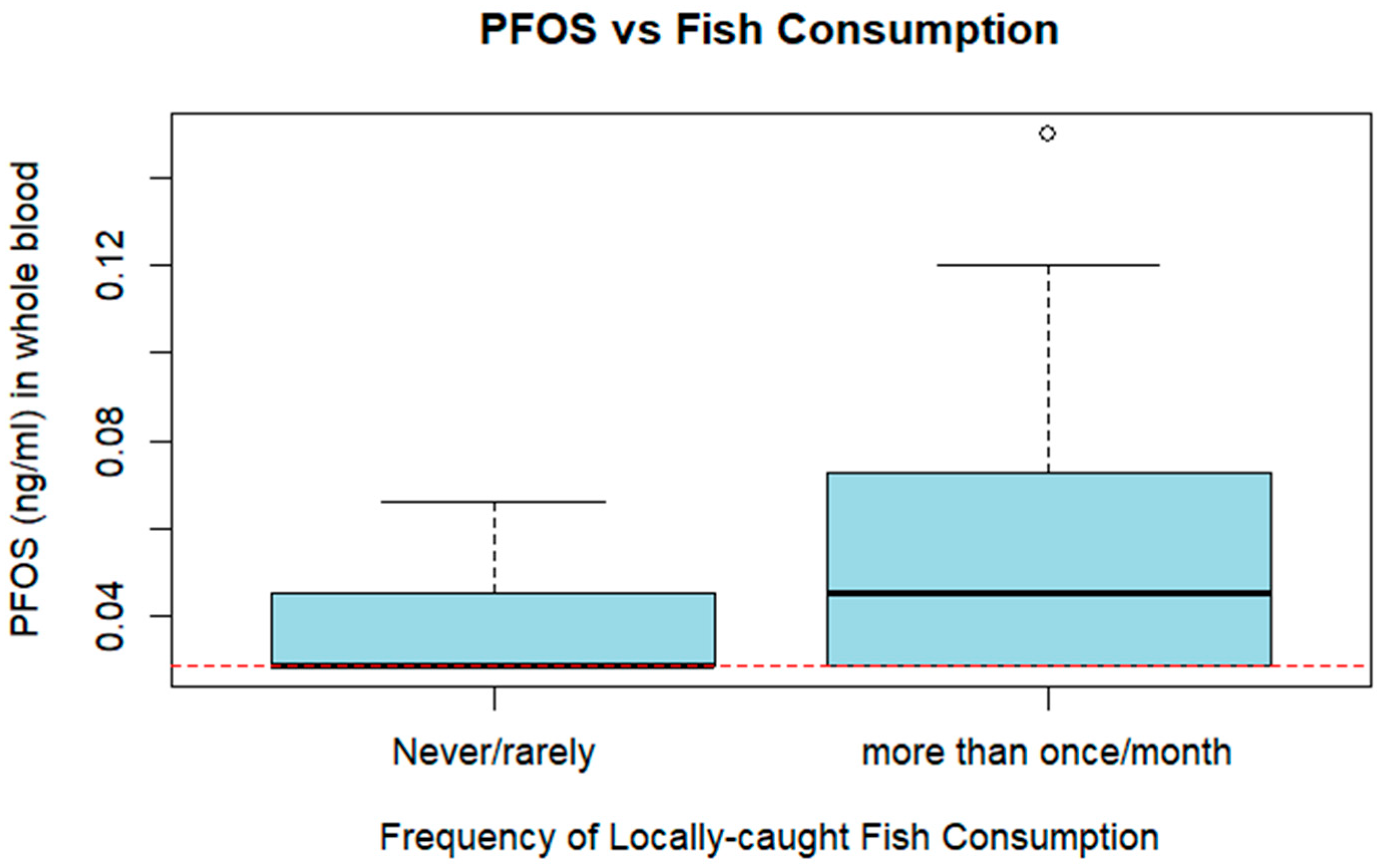

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATSDR | Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (USA) |

| CEPHED | Center for Public Health and Urban Development (Nepal) |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency (USA) |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| LMIC | Low- and middle-income countries |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| NIEHS | National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (USA) |

| NPR | Nepali rupees |

| NTP | National Toxicology Program (USA) |

| PFAS | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFDA | Perfluorodecanoic acid |

| PFHxS | Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid |

| PFNA | Perfluorononanoic acid |

| PFOA | L- Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOS | L-Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid |

| PFUnDA | Perfluoroundecanoic acid |

| POPs | Persistent organic pollutants |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| USD | United States dollars |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| PFAS | Full Name | % Above LOD | LOD (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFHxA | Perfluorohexanoic acid | 0 | 0.08 |

| PFHpA | Perfluoroheptanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| Linear PFOA | L-Perfluorooctanoic acid | 12.5 | 0.12 |

| Branched PFOA | Br-Perfluorooctanoic acid | 0 | 0.12 |

| Total PFOA | 12.5 | 0.12 | |

| PFNA | Perfluorononanoic acid | 25 | 0.04 |

| PFDA | Perfluorodecanoic acid | 2.08 | 0.04 |

| PFUnDA | Perfluoroundecanoic acid | 2.08 | 0.04 |

| PFDoA | Perfluorododecanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFTrDA | Perfluorotridecanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFTeDA | Perfluorotetradecanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFHxDA | Perfluoro-n-hexadecanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFBS | Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.18 |

| PFPeS | Perfluoropentanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFHxS | Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid | 4.17 | 0.04 |

| PFHpS | Perfluoroheptanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.08 |

| Linear PFOS | L-Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | 45.83 | 0.04 |

| Branched PFOS | Br-Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| Total PFOS | 45.83 | 0.04 | |

| PFNS | Perfluorononanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFDS | Perfluorodecanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFDoS | Perfluorododecanesulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| 5:3 FTCA | 5:3 Fluorotelomer carboxylic acid | 0 | 0.077 |

| 7:3 FTCA | 7:3 Fluorotelomer carboxylic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| 6:2 FTCA | 6:2 Fluorotelomer carboxylic acid | 0 | 0.055 |

| 8:2 FTCA | 8:2 Fluorotelomer carboxylic acid | 0 | 0.045 |

| PFOSA | Perfluorooctanesulfonamide | 0 | 0.04 |

| NMeFOSAA | N-methylperfluorooctane sulfonamidoacetic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| NEtFOSAA | N-ethylperfluorooctane sulfonamidoacetic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| 4:2 FTS | 4:2 Fluorotelomer sulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| 8:2 FTS | 8:2 Fluorotelomer sulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| 10:2 FTS | 10:2 Fluorotelomer sulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| GenX | HFPO-DA | 0 | 0.04 |

| 9Cl-PF3ONS | 9-chlorohexanedecafluoro-3-oxanone-1-sulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| 11Cl-PF3OUdS | 11-chloroeicosafluoro-3-oxaundecane-1-sulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| ADONA | 4,8-Dioxa-3H-perfluorononanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFECHS | Perfluoro-4-ethylcyclohexanesulfonate | 0 | 0.04 |

| NFDHA | Nonafluoro-3,6-dioxaheptanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFMBA | Perfluoro-4-methoxybutanoic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFEESA | Perfluoro(2-ethoxyethane) sulfonic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

| PFO5DA | Perfluoro-3,5,7,9,11-pentaoxadodecanoic acid | 0 | 0.08 |

| PFPE-1 | Perfluoroalkylether | 0 | 0.094 |

| Hydro-PS Acid | Hydrogen-substituted Perfluoroheptane sulfonate | 0 | 0.04 |

| 6:2 FTUCA | 6:2 fluorotelomer unsaturated carboxylic acid | 0 | 0.054 |

| 8:2 FTUCA | 8:2 Fluorotelomer unsaturated carboxylic acid | 0 | 0.04 |

References

- National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). 25 February 2025. Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/pfc (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Von Holst, H.; Nayak, P.; Dembek, Z.; Buehler, S.; Echeverria, D.; Fallacara, D.; John, L. Perfluoroalkyl substances exposure and immunity, allergic response, infection, and asthma in children: Review of epidemiologic studies. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Our Current Understanding of the Human Health and Environmental Risks of PFAS. 26 November 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/our-current-understanding-human-health-and-environmental-risks-pfas (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Grandjean PAndersen, E.W.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Nielsen, F.; Mølbak, K.; Weihe, P.; Heilmann, C. Serum vaccineantibody concentrations in children exposed to perfluorinated compounds. JAMA 2012, 307, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdonough, C.A.; Ward, C.; Hu, Q.; Vance, S.; Higgins, C.P.; Dewitt, J.C.; Carolina, N. Immunotoxicity of an Electrochemically Fluorinated Aqueous Film-Forming Foam. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 178, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderko, L.; Pennea, E. Exposures to per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): Potential risks to reproductive and children’s health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2020, 50, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Toxicology Program. Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid or Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. NTP Monograph. September 2016. Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/pfoa_pfos/pfoa_pfosmonograph_508.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Betts, K.S. Perfluoroalkyl acids: What is the evidence telling us? Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.; Balan, S.A.; Scheringer, M.; Trier, X.; Goldenmann, G.; Cousins, I.T.; Diamond, M.; Fletcher, T.; Higgins, C.; Lindeman, A.E.; et al. The Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, A107–A111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurwadkar, S.; Dane, J.; Kanel, S.R.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Cawdrey, R.W.; Ambade, B.; Struckhoff, G.C.; Wilkin, R. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in water and wastewater: A critical review of their global occurrence and distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 809, 151003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.W.; Shahul Hamid, F.; Yusoff, I.; Chan, V. A review of PFAS research in Asia and occurrence of PFOA and PFOS in groundwater, surface water and coastal water in Asia. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 22, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, L.A.; Mabury, S.A. Certain Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Associated with Aqueous Film Forming Foam Are Widespread in Canadian Surface Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13603–13613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, J.; Sun, H.; Xie, Z. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the urban, industrial, and background atmosphere of Northeastern China coast around the Bohai Sea: Occurrence, partitioning, and seasonal variation. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 167, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssebugere, P.; Sillanpää, M.; Matovu, H.; Wang, Z.; Schramm, K.-W.; Omwoma, S.; Wanasolo, W.; Ngeno, E.C.; Odongo, S. Environmental levels and human body burdens of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances in Africa: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, T.; Asiseh, F.; Jefferson-Moore, K.; Obeng-Gyasi, E. The Association of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Serum Levels and Allostatic Load by Country of Birth and the Length of Time in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Kumar, N.; Kumar Yadav, A.; Singh, R.; Kumar, K. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a health hazard: Current state of knowledge and strategies in environmental settings across Asia and future perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 145064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groffen, T.; Nkuba, B.; Wepener, V.; Bervoets, L. Risks posed by per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) on the African continent, emphasizing aquatic ecosystems. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2021, 17, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, K.; Clifford, H.; Taruscio, T.; Potocki, M.; Solomon, G.; Ritari, M.; Napper, I.; Gajurel, A.; Mayewski, P. Deposition of PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ on Mt. Everest. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 144421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Public Health and Environmental Development (CEPHED). NEPAL PFAS Country Situation Report. 2019. Available online: https://ipen.org/sites/default/files/documents/nepal_pfas_country_situation_report_mar_2019.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Tan, B.; Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Luo, W.; Lu, Y.; Romesh, K.Y.; Giesy, J.P. Perfluoroalkyl substances in soils around the Nepali Koshi River: Levels, distribution, and mass balance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 9201–9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuli, R.P.; Fujiwara, T.; Umezaki, M.; Watanabe, C. Association of cord blood levels of lead, arsenic, and zinc with neurodevelopmental indicators in newborns: A birth cohort study in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. Environ. Res. 2013, 121, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Exposure Assessment Technical Tools. July 2018. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/php/pfas-exposure-assessment-technicaltools/index.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Kato, K.; Wanigatunga, A.A.; Needham, L.L.; Calafat, A.M. Analysis of blood spots for polyfluoroalkyl chemicals. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 656, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Kannan, K.; Wu, Q.; Bell, E.M.; Druschel, C.M.; Caggana, M.; Aldous, K.M. Analysis of polyfluoroalkyl substances and bisphenol A in dried blood spots by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 4127–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poothong, S.; Papadopoulou, E.; Lundanes, E.; Padilla-Sánchez, J.A.; Thomsen, C.; Haug, L.S. Dried blood spots for reliable biomonitoring of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chace, D.H.; De Jesús, V.R.; Spitzer, A.R. Clinical Chemistry and Dried Blood Spots: Increasing Laboratory Utilization by Improved Understanding of Quantitative Challenges. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 2791–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, T.A.; Kler, J.S.; Bae, Y.; Chen, J.; Ladror, D.T.; Iyer, R.; Nunes, D.A.; Montgomery, N.D.; Pleil, J.D.; Funk, W.E. A state-of-the-science review and guide for measuring environmental exposure biomarkers in dried blood spots. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.-H.; Batterman, S. Estimating blood volume on dried blood spots. Forensic Chem. 2024, 37, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carignan, C.C.; Bauer, R.A.; Patterson, A.; Phomsopha, T.; Redman, E.; Stapleton, H.M.; Higgins, C.P. Self-Collection Blood Test for PFASs: Comparing Volumetric Microsamplers with a Traditional Serum Approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7950–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Office, Government of Nepal. Nepal Living Standard Survey IV. 2024. Available online: https://data.nsonepal.gov.np/dataset/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Fan, X.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; Ben, Y.; Naidu, R.; Dong, Z. Global Exposure to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Associated Burden of Low Birthweight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 4282–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbo, N.; Stoiber, T.; Naidenko, O.V.; Andrews, D.Q. Locally caught freshwater fish across the United States are likely a significant source of exposure to PFOS and other perfluorinated compounds. Environ. Res. 2023, 220, 115165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soudani, M.; Hegg, L.; Rime, C.; Coquoz, C.; Grosjean, D.B.; Danza, F.; Solcà, N.; Lucarini, F.; Staedler, D. Determination of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in six different fish species from Swiss lakes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 6377–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pollutants Elimination Network. PFAS Pollution Across the Middle East and Asia. April 2019. Available online: https://ipen.org/documents/pfas-pollution-across-middle-east-and-asia (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Aquaculture Growth Potential in Nepal: World Aquaculture Performance Indicators (WAPI) Factsheet to Facilitate Evidence-Based Policymaking and Sector Management in Aquaculture. March 2021. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/5174733c-6700-4e54-a357-cd8e7a5fbf1f/content#:~:text=Nepal’s%20per%20capita%20protein%20intake,demand%20growth%20(slide%2066) (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Department of Food Technology and Quality Control (DFTQC). Food Composition Table for Nepal. Kathmandu: National Nutrition Program Ministry of Agriculture Development, Government of Nepal. 2012. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/food_composition/documents/regional/Nepal_Food_Composition_table_2012.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Gurung, T.B. Role of inland fishery and aquaculture for food and nutrition security in Nepal. Agric. Food Secur. 2016, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, M.; Sapozhnikova, Y.; Taylor, R.B.; Ng, C. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) measured in seafood from a cross-section of retail stores in the United States. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Nepal National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC219329/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- United Nations. Nepal: Voluntary National Review 2020. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/memberstates/nepal (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Lin, E.Z.; Nason, S.L.; Zhong, A.; Fortner, J.; Godri Pollitt, K.J. Trace analysis of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) in dried blood spots—Demonstration of reproducibility and comparability to venous blood samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Full Cohort (n = 73) Mean (SD) | Subset (n = 48) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.00 (0.03) | 15.01 (0.03) |

| Annual family income (NPR) | 648,278 (542,865.10) | 670,213 (540,645.70) |

| Annual family income (USD) | 4862 (4071.89) | 5027 (4054.84) |

| Water consumption per day (L) | 1.28 (0.79) | 1.39 (0.89) |

| Sex: Male | 33 (45.21%) | 21 (43.75%) |

| Sex: Female | 40 (54.79%) | 27 (56.25%) |

| Primary drinking water: Piped supply | 42 (57.53%) | 29 (61.70%) |

| Primary drinking water: Tubewell | 27 (36.99%) | 17 (36.17%) |

| Primary drinking water: Rainwater | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Primary drinking water: Bottled water | 1 (1.37%) | 1 (2.13%) |

| Fish consumption: Often (>1 time/month) | 25 (34.25%) | 16 (33.33%) |

| Fish consumption: Occasionally (≤1 time/month) | 15 (20.55%) | 10 (20.83%) |

| Fish consumption: Rarely or never | 32 (43.84%) | 22 (45.83%) |

| PFAS | Full Name | Number Above LOD | Percent Above LOD | Mean (SD) | Minimum (ng/mL) | Maximum (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFHxS | Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid | 2 | 4.17 | † | <LOD | 0.058 |

| PFOS | L-Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid | 22 | 45.83 | 0.062 (0.03) | <LOD | 0.15 |

| PFOA | L-Perfluorooctanoic acid | 6 | 12.5 | † | <LOD | 0.34 |

| PFNA | Perfluorononanoic acid | 12 | 25 | 0.054 (0.01) | <LOD | 0.094 |

| PFDA | Perfluorodecanoic acid | 1 | 2.08 | † | <LOD | 0.1 |

| PFUnDA | Perfluoroundecanoic acid | 1 | 2.08 | † | <LOD | 0.079 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ward, L.M.; Bhandari, S.; Aleem, H.; Goodrich, J.M.; Parajuli, R.P. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Blood Spot per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Adolescents in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. Epidemiologia 2026, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010005

Ward LM, Bhandari S, Aleem H, Goodrich JM, Parajuli RP. A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Blood Spot per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Adolescents in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. Epidemiologia. 2026; 7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleWard, Lauren Marie, Shristi Bhandari, Hafsa Aleem, Jaclyn M. Goodrich, and Rajendra Prasad Parajuli. 2026. "A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Blood Spot per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Adolescents in Chitwan Valley, Nepal" Epidemiologia 7, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010005

APA StyleWard, L. M., Bhandari, S., Aleem, H., Goodrich, J. M., & Parajuli, R. P. (2026). A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Blood Spot per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Adolescents in Chitwan Valley, Nepal. Epidemiologia, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia7010005