Population Attributable Fraction of Tobacco Use and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Analysis of the ENSANUT 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Dependent Variable: Diabetes Diagnosis

2.4. Primary Exposure Variable: Active Tobacco Use

2.5. Classification by Intensity of Tobacco Use

2.6. Covariates

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Estimation of the Population Attributable Fraction (PAF)

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Association Between Smoking and Diabetes

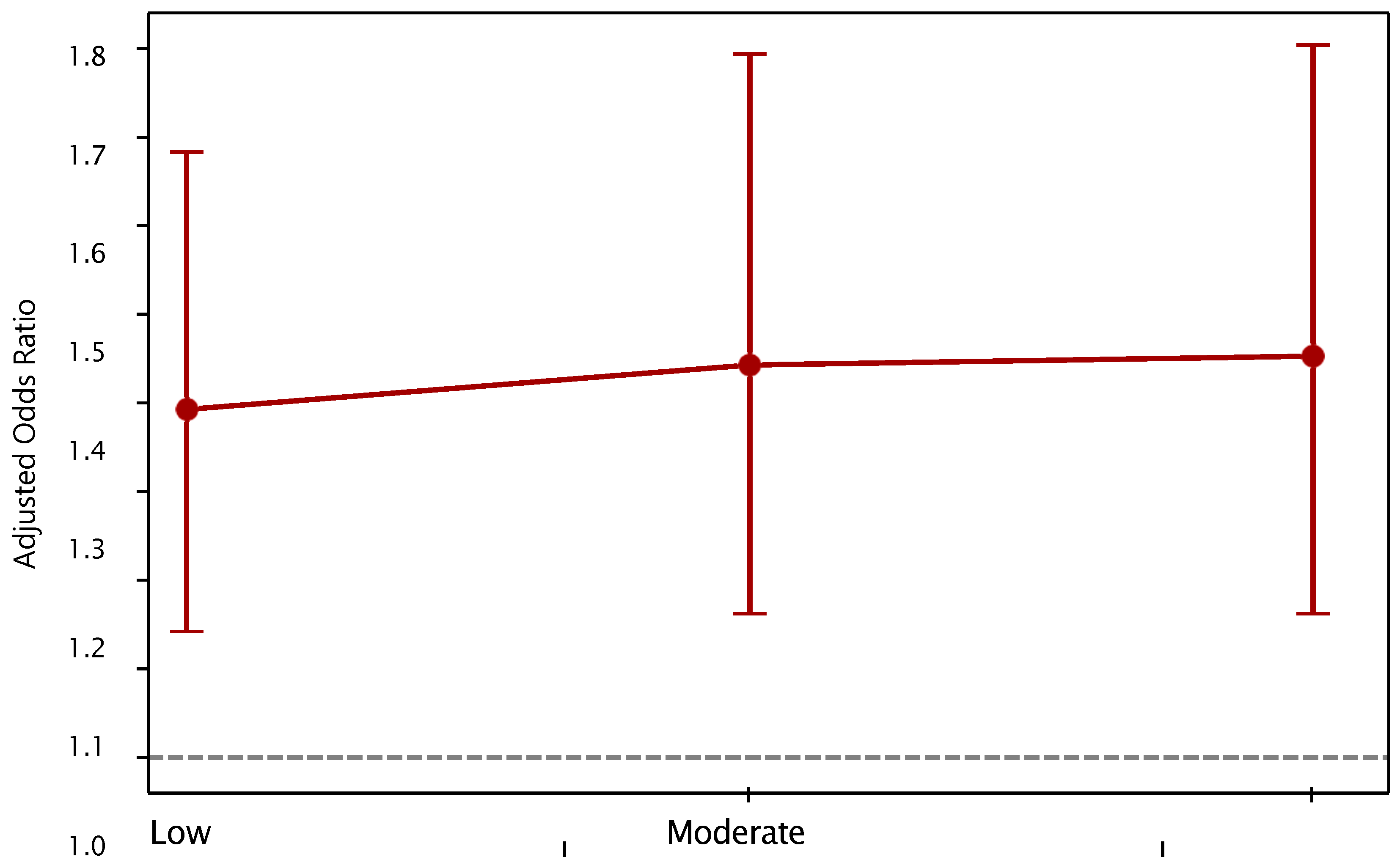

3.2. Analysis by Intensity of Use

3.3. Estimation of the Population Attributable Fraction (PAF)

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence Intervals |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| DALYs | Disability Adjusted Life Years |

| ENSANUT | National Health and Nutrition Survey from México |

| ETS | Environmental tobacco smoke |

| NCDs | Chronic non-communicable diseases |

| OR | Odds Ratios |

| ORa | Adjusted Odds Ratios |

| PAF | Population Attributable Fraction |

| PeP_e | Proportion of Individuals Exposed Among Cases |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| WHO | Word Health Organization |

| YLD | Years of life lost due to disability |

| YLL | Years of life lost due to premature death |

References

- Guerrero-López, C.M.; Serván-Mori, E.; Miranda, J.J.; Jan, S.; Orozco-Núñez, E.; Downey, L.; Feeny, E.; Heredia-Pi, I.; Flamand, L.; Nigenda, G.; et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases and behavioural risk factors in Mexico: Trends and gender observational analysis. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas (10th ed.). 2023, p. 5. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Basto-Abreu, A.; López-Olmedo, N.; Rojas-Martínez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Moreno-Banda, G.L.; Carnalla, M.; Rivera, J.A.; Romero-Martinez, M.; Barquera, S.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Prevalencia de prediabetes y diabetes en México: Ensanut 2022. Salud Publica De México 2023, 65, s163–s168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto-Abreu, A.C.; López-Olmedo, N.; Rojas-Martínez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; De la Cruz-Góngora, V.V.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Barquera, S.; Villalpando, S.; et al. Prevalence of diabetes and glycemic control in Mexico: National results from 2018 and 2020. Salud Pública De México 2021, 63, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agudelo-Botero, M.; Dávila-Cervantes, C.A. Mortality and Years of Life Lost from Cardiometabolic Diseases in Mexico: National and State-Level Trends, 1998–2022. Public Health Rep. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Martínez, R.; Escamilla-Nuñez, C.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.; Castro-Porras, L.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Lazcano-Ponce, E. Trends in the mortality of diabetes in Mexico from 1998 to 2022: A joinpoint regression and age-period-cohort effect analysis. Public Health 2024, 226, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Antonio-Villa, N.E.; Fermín-Martínez, C.A.; Fernández-Chirino, L.; Vargas-Vázquez, A.; Ramírez-García, D.; Basile-Alvarez, M.R.; Hoyos-Lázaro, A.E.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Wexler, D.J.; et al. Diabetes-Related Excess Mortality in Mexico: A Comparative Analysis of National Death Registries Between 2017–2019 and 2020. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 2957–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Endomba, F.T.; Ngouo, A.; Nkeck, J.R.; Nyaga, U.F.; Kaze, A.D.; Bigna, J.J. Active smoking among people with diabetes mellitus or hypertension in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynales-Shigematsu, L.M. Tobacco and cancer: Epidemiology and new perspectives of prevention and monitoring in Mexico. Salud Pública De México 2016, 58, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderick, P.; Turner, V.; Readshaw, A.; Dogar, O.; Siddiqi, K. The global prevalence of tobacco use in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 154, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, Y.; Han, K.; Choi, M.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.M.; Nam, G.E. Association of smoking status with the risk of type 2 diabetes among young adults: A nationwide cohort study in South Korea. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022, 24, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Goto, A.; Mizoue, T. Smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes in Japan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.A. Smoking and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2012, 36, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagna, D.; Alamo, A.; Di Pino, A.; Russo, C.; Calogero, A.E.; Purrello, F.; Polosa, R. Smoking and diabetes: Dangerous liaisons and confusing relationships. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, J.; Huang, T. Smoking status and type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease: A comprehensive analysis of shared genetic etiology and causal relationship. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 809445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Dastani, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Eskandarioun, M.; Hassani Goodarzi, T.; Torabian, A.; Talebnia, S.E. Association Rule Mining Analysis of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in the CDC Diabetes Health Indicators Dataset. Infosci. Trends 2025, 2, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willi, C.; Bodenmann, P.; Ghali, W.A.; Faris, P.D.; Cornuz, J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007, 298, 2654–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loretan, C.G.; Cornelius, M.E.; Jamal, A.; Cheng, Y.J.; Homa, D.M. Cigarette smoking among US adults with selected chronic diseases associated with smoking, 2010–2019. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2022, 19, E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Archive. Tobacco Control Interventions. Health 2023, 6, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Flor, L.S.; Anderson, J.A.; Ahmad, N.; Aravkin, A.; Carr, S.; Dai, X.; Gil, G.F.; Hay, S.I.; Malloy, M.J.; McLaughlin, S.A.; et al. Health effects associated with exposure to secondhand smoke: A Burden of Proof study. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Wang, Y.; Talaei, M.; Hu, F.B.; Wu, T. Relation of active, passive, and quitting smoking with incident type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycett, D.; Nichols, L.; Ryan, R.; Farley, A.; Roalfe, A.; Mohammed, M.A.; Szatkowski, L.; Coleman, T.; Morris, R.; Farmer, A.; et al. The association between smoking cessation and glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A THIN database cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Shi, F.; Ma, Y.; Yang, D.; Yu, C.; Cao, J. The global burden of type 2 diabetes attributable to tobacco: A secondary analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 905367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco and Diabetes Internet. 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/375763/9789240088580-spa.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Samet, J.M. Los riesgos del tabaquismo activo y pasivo. Salud Pública De México 2002, 44, s144–s160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudo, L.S. El fumador pasivo. Monogr. Tab. 2004, 16 (Suppl. 2), 83. [Google Scholar]

- Encuesta Global de Tabaquismo en Adultos (GATS). México 2023. Gobierno de México, Departamento de Prevención y Control del Tabaquismo. 2023. Available online: https://portal.insp.mx/control-tabaco/reportes/encuesta-global-de-tabaquismo-en-adultos-gats-mexico-2023 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Wang, M.; Maimaitiming, M.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.J. Global trends in deaths and disability-adjusted life years of diabetes attributable to second-hand smoke and the association with smoke-free policies. Public Health 2024, 228, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Z. Global burden of type 2 diabetes attributable to secondhand smoke: A comprehensive analysis from the GBD 2021 study. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1506749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, M.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Bautista-Arredondo, S.; Colchero, M.A.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Martínez-Barnetche, J.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M.; Mendoza-Alvarado, L.R.; et al. Metodología de la Encuesta nacional de Salud y nutrición 2021. Salud Pública De México 2021, 63, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorca, J.; Fariñas-Álvarez, C.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M. Fracción atribuible poblacional: Cálculo e interpretación. Gac. Sanit. 2001, 15, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.; Drescher, K. Maximum likelihood estimation of the attributable fraction from logistic models. Biometrics 1993, 49, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, N.; Chen, G.; Wan, Q.; Yan, L.; Wang, G.; Qin, Y.; Luo, Z.; Tang, X.; Huo, Y.; et al. Interaction between smoking and diabetes in relation to subsequent risk of cardiovascular events. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Hu, Y.; Zong, G.; Pan, A.; E Manson, J.; Rexrode, K.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Smoking cessation and weight change in relation to cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlach, V.; Vergès, B.; Al-Salameh, A.; Bahougne, T.; Benzerouk, F.; Berlin, I.; Clair, C.; Mansourati, J.; Rouland, A.; Thomas, D.; et al. Smoking and diabetes interplay: A comprehensive review and joint statement. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 48, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbaniang, S.P.; Lhungdim, H.; Chauhan, S.; Srivastava, S. Interaction of multiple risk factors and population attributable fraction for type 2 diabetes and hypertension among adults aged 15–49 years in Northeast India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaobelina, K.; Dow, C.; Mancini, F.R.; Dartois, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.; Balkau, B.; Bonnet, F.; Fagherazzi, G. Population attributable fractions of the main type 2 diabetes mellitus risk factors in women: Findings from the French E3N cohort. J. Diabetes 2019, 11, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-García, D.; Fermín-Martínez, C.A.; Sánchez-Castro, P.; Núñez-Luna, A.; Basile-Alvarez, M.R.; Fernández-Chirino, L.; Vargas-Vázquez, A.; Díaz-Sánchez, J.P.; Kammar-García, A.; Almeda-Valdés, P.; et al. Smoking, all-cause, and cause-specific mortality in individuals with diabetes in Mexico: An analysis of the Mexico city prospective study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloupka, F.J.; Yurekli, A.; Fong, G.T. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tob. Control 2012, 21, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollo, M.; Younie, S.; Wakefield, M.; Freeman, J.; Icasiano, F. Impact of tobacco tax reforms on tobacco prices and tobacco use in Australia. Tob. Control 2003, 12 (Suppl. 2), ii59–ii66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynales-Shigematsu, L.M.; Sáenz-de-Miera, B.; Llorente, B.; Maldonado, N.; Shanon, G.; Jha, P. Benefits of the cigarette tax in Mexico, by sex and income quintileBenefícios do imposto sobre cigarros no México: Análise por sexo e quintil de renda. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2022, 46, e80. [Google Scholar]

- Milián, R.P.; Enríquez, M.E.A. Programas de intervención aplicados en población mexicana para la prevención de enfermedades no transmisibles 2010–2020. Anu. Investig. UM 2021, 2, 134–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, D.; Virgolini, M. Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo 2005: Resultados principales: Prevalencia de factores de riesgo de enfermedades cardiovasculares en la Argentina. Rev. Argent. Cardiol. 2007, 75, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta Ruiz, L.X.; Merchán, M.A.; Orjuela Vargas, L. Diabetes mellitus tipo 2: Latinoamérica y Colombia, análisis del último quinquenio. Rev. Med. 2023, 31, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Mendoza, M.D. Factores de riesgo de diabetes mellitus tipo 2 en población adulta. Barranquilla, Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2019, 6, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.D.; Molinatti, F.; Peláez, E. Comparison of mortality attributable to tobacco in selected Latin American countries. Población Salud Mesoamérica 2019, 16, 154–174. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Control | Cases | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n * | % | [CI 95%] | % | [CI 95%] | % | [CI 95%] | |||

| History of tobacco | |||||||||

| Non-smoker | 7823 | 63.6 | [62.3, 64.9] | 1091 | 62.7 | [59.1, 66.2] | 8914 | 63.5 | [62.2, 64.7] |

| Current smoker | 2001 | 19.7 | [18.6–20.8] | 183 | 14.3 | [11.6–17.6] | 2184 | 19.1 | [18.1, 20.2] |

| Former smoker | 1887 | 16.8 | [15.8–17.8] | 325 | 23.0 | [19.7–26.6] | 2212 | 17.4 | [16.5, 18.4] |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Man | 4730 | 48.6 | [47.3, 49.9] | 517 | 41.6 | [38.5, 44.9] | 5247 | 47.9 | [46.7, 49.0] |

| Woman | 7062 | 51.4 | [50.1, 52.7] | 1093 | 58.4 | [55.1, 61.5] | 8155 | 52.1 | [51.0, 53.3] |

| Area | |||||||||

| Rural | 2823 | 20.1 | [18.8, 21.6] | 363 | 17.7 | [15.4, 20.3] | 3186 | 19.9 | [18.5, 21.3] |

| Urban | 8969 | 79.9 | [78.4, 81.2] | 1247 | 82.3 | [79.7, 84.6] | 10,216 | 80.1 | [78.7, 81.5] |

| Region | |||||||||

| North Pacific | 1466 | 9.5 | [8.6, 10.6] | 189 | 8.9 | [6.9, 11.4] | 1655 | 9.5 | [8.5, 10.5] |

| Frontier | 855 | 12.9 | [11.7, 14.3] | 125 | 13.3 | [10.5, 16.8] | 980 | 13.0 | [11.8, 14.3] |

| Pacific-Central | 967 | 11.0 | [10.4, 11.7] | 118 | 9.4 | [7.4, 11.8] | 1085 | 10.9 | [10.3, 11.4] |

| North Central | 2595 | 12.6 | [12.0, 13.2] | 372 | 12.3 | [10.7, 14.2] | 2967 | 12.6 | [12.1, 13.1] |

| Center | 909 | 9.7 | [9.1, 10.5] | 124 | 11.8 | [8.6, 15.9] | 1033 | 10.0 | [9.1, 10.9] |

| Cd. Mexico | 1226 | 8.2 | [7.8, 8.7] | 177 | 8.8 | [7.3, 10.6] | 1403 | 8.3 | [7.9, 8.7] |

| Edo. Mexico | 1101 | 13.7 | [13.0, 14.5] | 153 | 13.0 | [10.9, 15.5] | 1254 | 13.7 | [13.0, 14.3] |

| South Pacific | 1180 | 12.2 | [11.1, 13.4] | 164 | 13.9 | [11.7, 16.4] | 1344 | 12.4 | [11.3, 13.5] |

| Peninsula | 1493 | 10.0 | [9.4, 10.6] | 188 | 8.6 | [7.1, 10.5] | 1681 | 9.9 | [9.3, 10.4] |

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||||

| Daily | 58 | 0.4 | [0.3, 0.6] | 9 | 0.5 | [0.2, 1.1] | 67 | 0.4 | [0.3, 0.6] |

| Weekly | 904 | 9.0 | [8.3, 9.9] | 45 | 2.7 | [1.8, 4.0] | 949 | 8.4 | [7.7, 9.2] |

| Monthly | 1096 | 10.9 | [10.0, 11.8] | 74 | 6.0 | [4.2, 8.4] | 1170 | 10.3 | [9.5, 11.2] |

| No consume | 9734 | 79.7 | [78.6, 80.7] | 1482 | 90.8 | [88.3, 92.8] | 11,216 | 80.9 | [79.8, 81.8] |

| Total | 11,792 | 100.0 | 1610 | 100.0 | 13,402 | 100.0 | |||

| Variable | ORa | CI 95% | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current smokers (vs. never) | 1.22 | 0.91–1.63 | 0.181 |

| Former smokers (vs. never) | 1.47 | 1.18–1.83 | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.06 | 1.05–1.06 | <0.001 |

| Women (Ref: Men) | 1.48 | 1.26–1.74 | <0.001 |

| Urban residence | 1.27 | 1.04–1.54 | 0.018 |

| Alcohol consumption (weekly) | 0.36 | 0.14–0.93 | 0.034 |

| Exposure Subgroup | ORa | IC 95% [ORa] | PeP_e | PAF (%) | CI 95% PAF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 1.36 | 1.12 | 1.65 | 0.38 | 10.10% | 4.07 | 14.97 |

| Low consumption | 1.39 | 1.14 | 1.68 | 0.32 | 9.00% | 3.93 | 12.95 |

| Moderate consumption | 1.44 | 1.16 | 1.79 | 0.35 | 10.70% | 4.83 | 15.45 |

| High consumption | 1.44 | 1.16 | 1.80 | 0.41 | 12.50% | 5.66 | 18.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campuzano, J.C.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Reynales, L.M.; Hernández, A.; Urrego, D.C. Population Attributable Fraction of Tobacco Use and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Analysis of the ENSANUT 2021. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040084

Campuzano JC, Rodríguez JM, Reynales LM, Hernández A, Urrego DC. Population Attributable Fraction of Tobacco Use and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Analysis of the ENSANUT 2021. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(4):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040084

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampuzano, Julio Cesar, Jorge Martin Rodríguez, Luz Myriam Reynales, Anaid Hernández, and Diana Carolina Urrego. 2025. "Population Attributable Fraction of Tobacco Use and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Analysis of the ENSANUT 2021" Epidemiologia 6, no. 4: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040084

APA StyleCampuzano, J. C., Rodríguez, J. M., Reynales, L. M., Hernández, A., & Urrego, D. C. (2025). Population Attributable Fraction of Tobacco Use and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Analysis of the ENSANUT 2021. Epidemiologia, 6(4), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040084