Respiratory Infant Mortality Rate by Month of Birth in Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. RSV Circulation and Respiratory Mortality

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

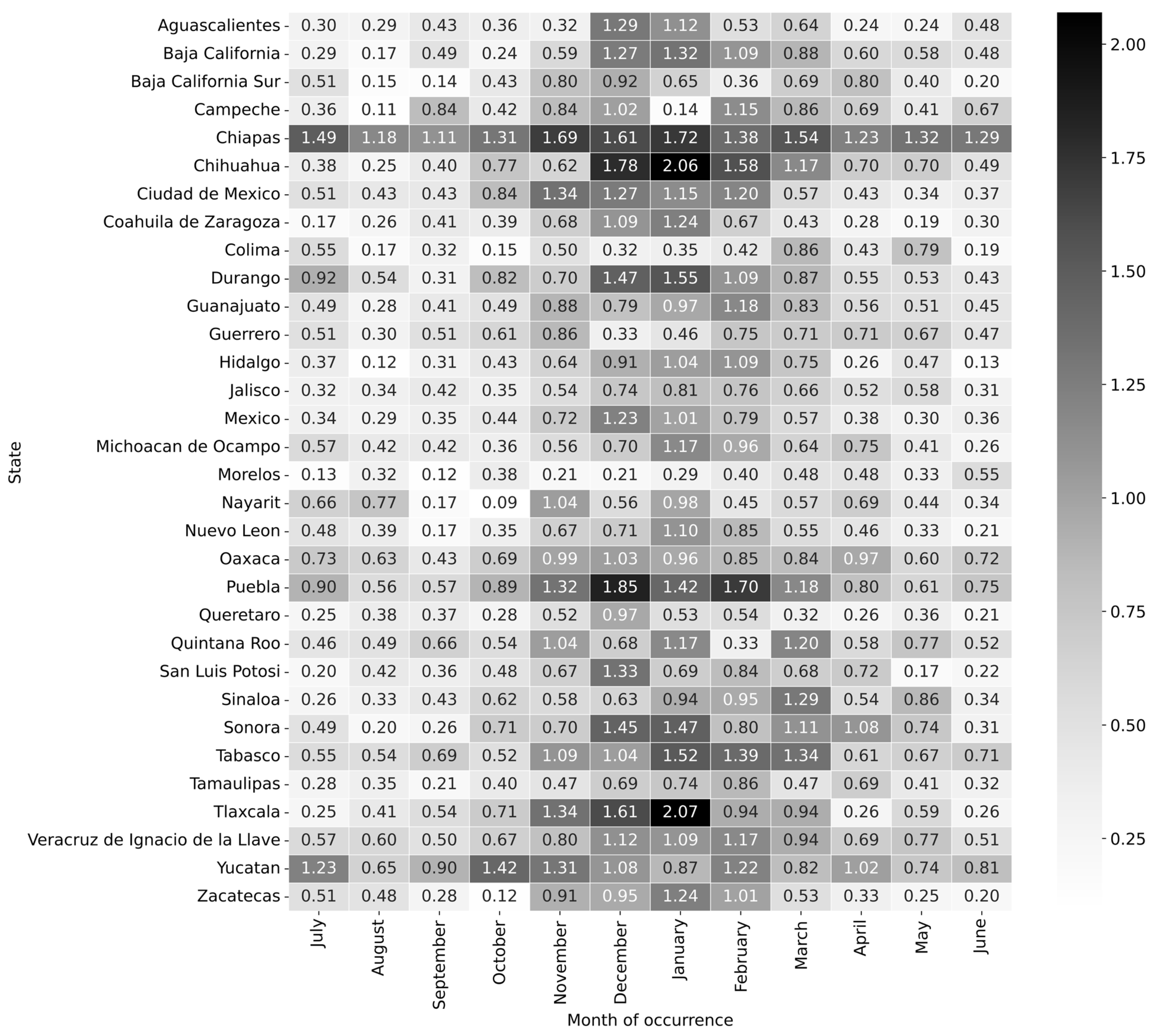

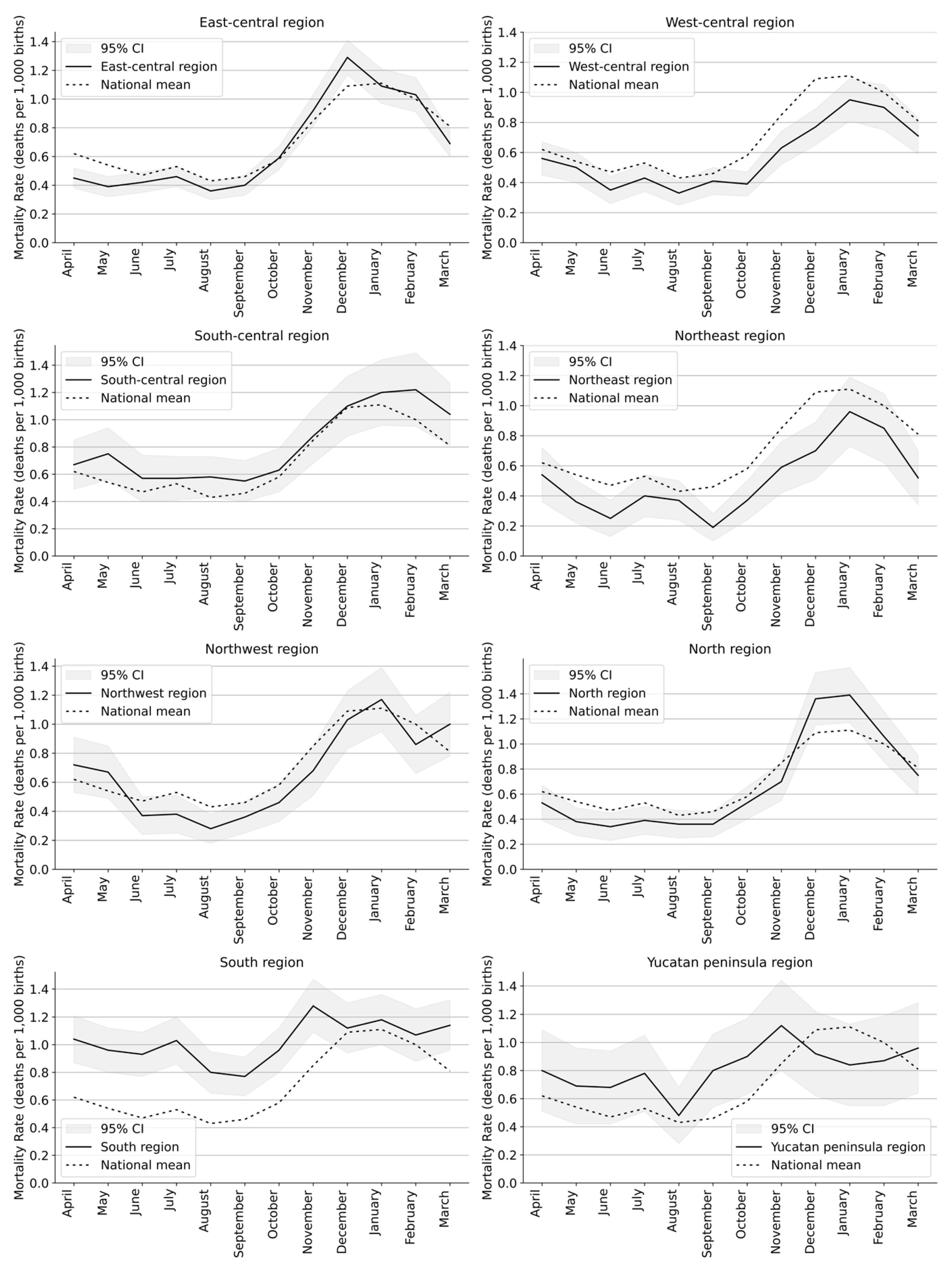

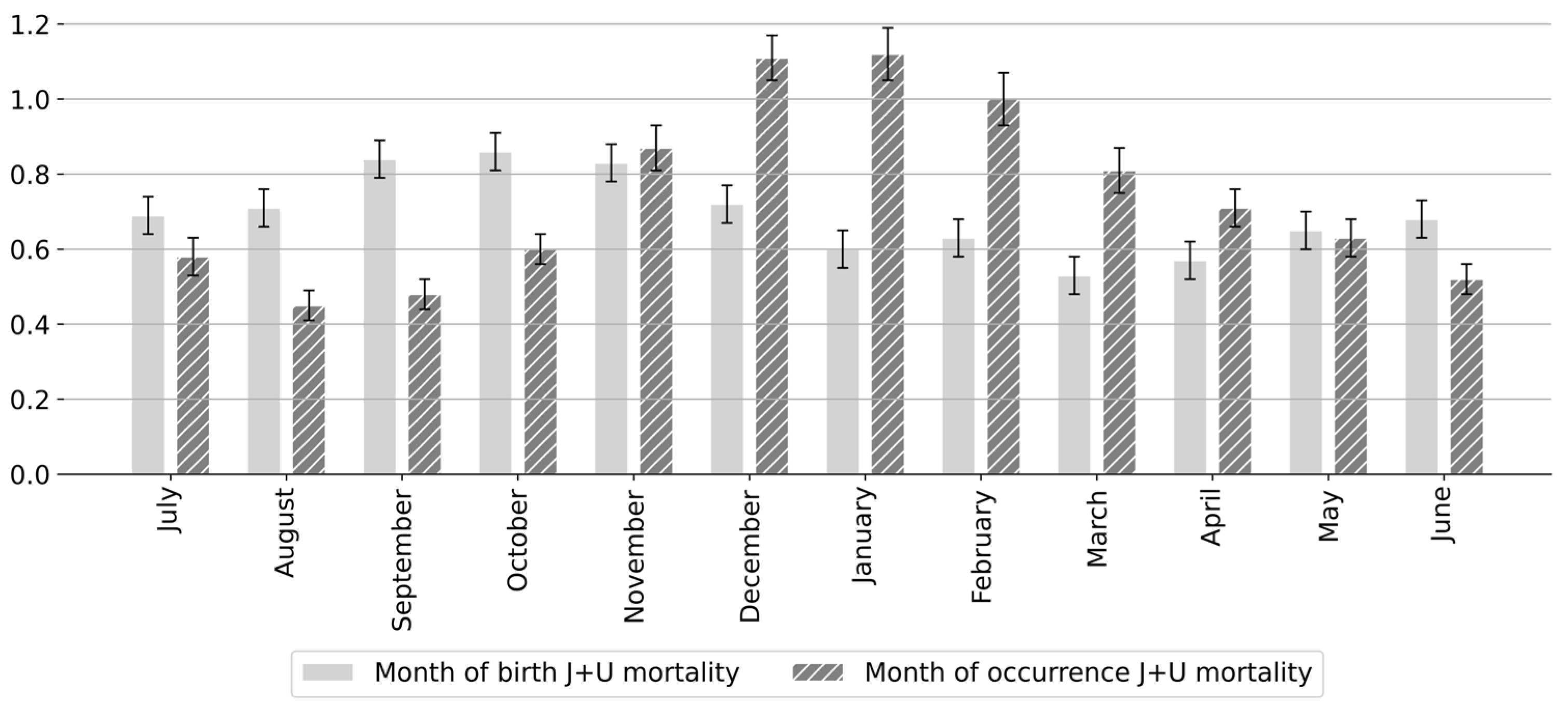

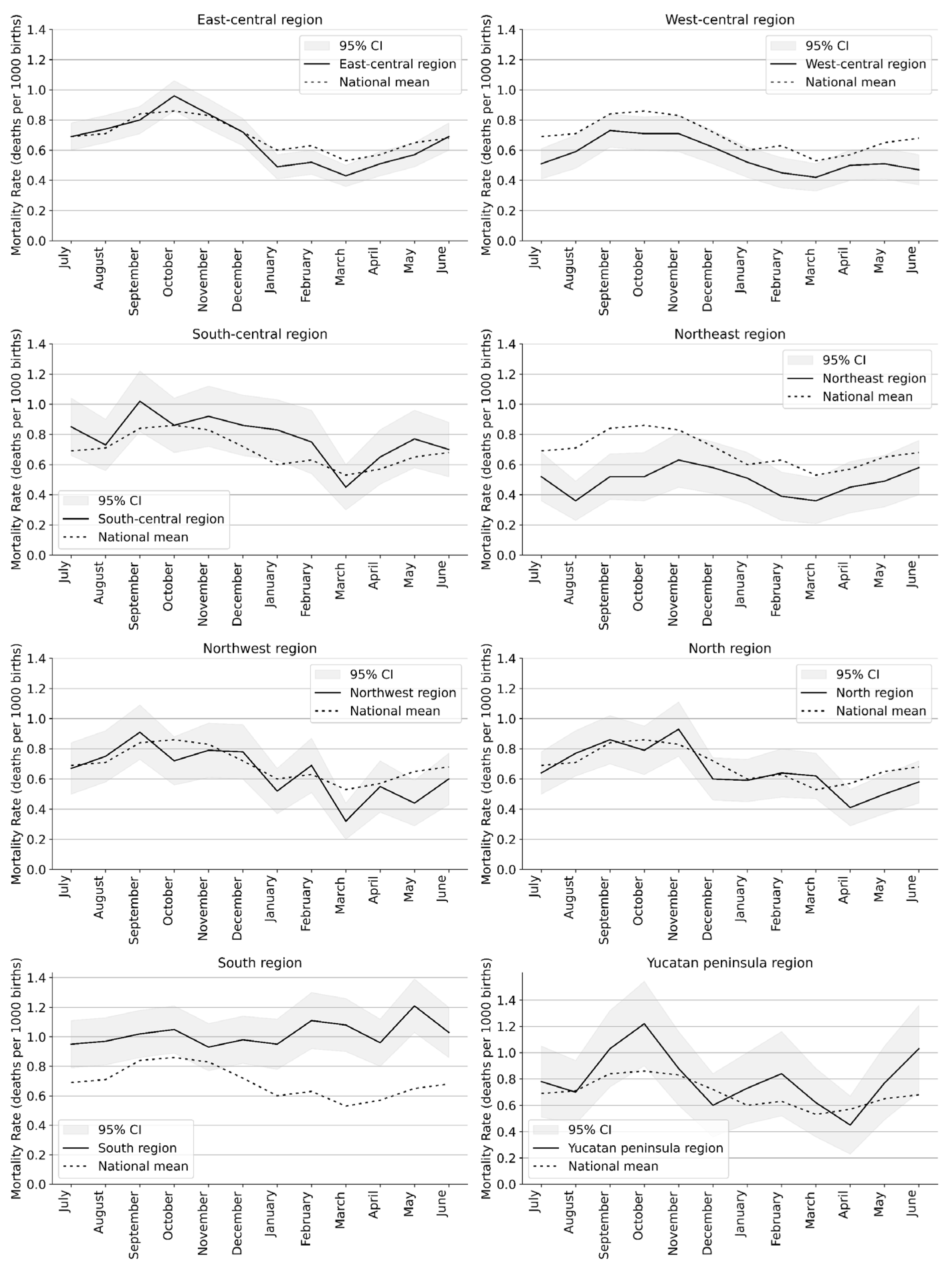

3.1. Respiratory Infant Mortality Rate

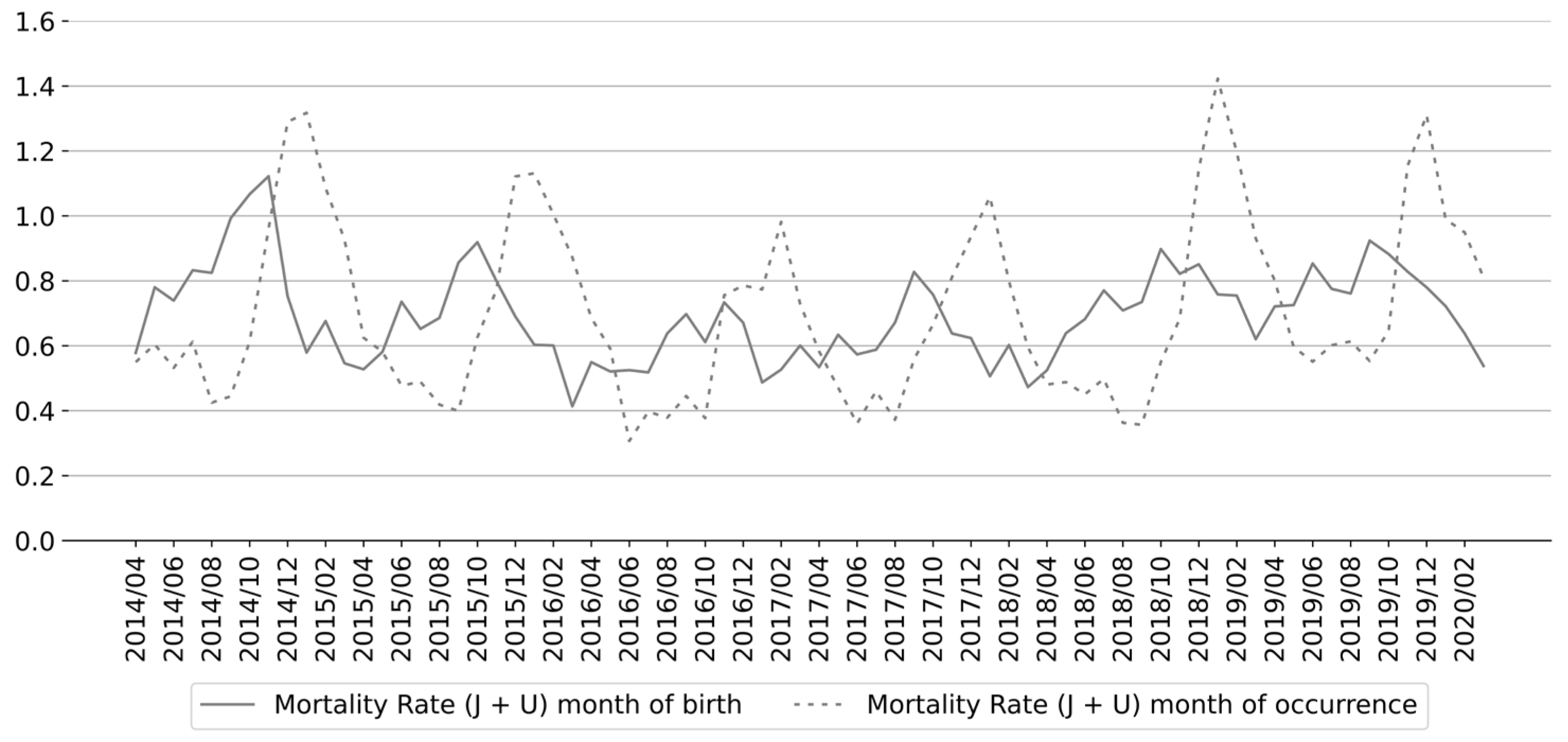

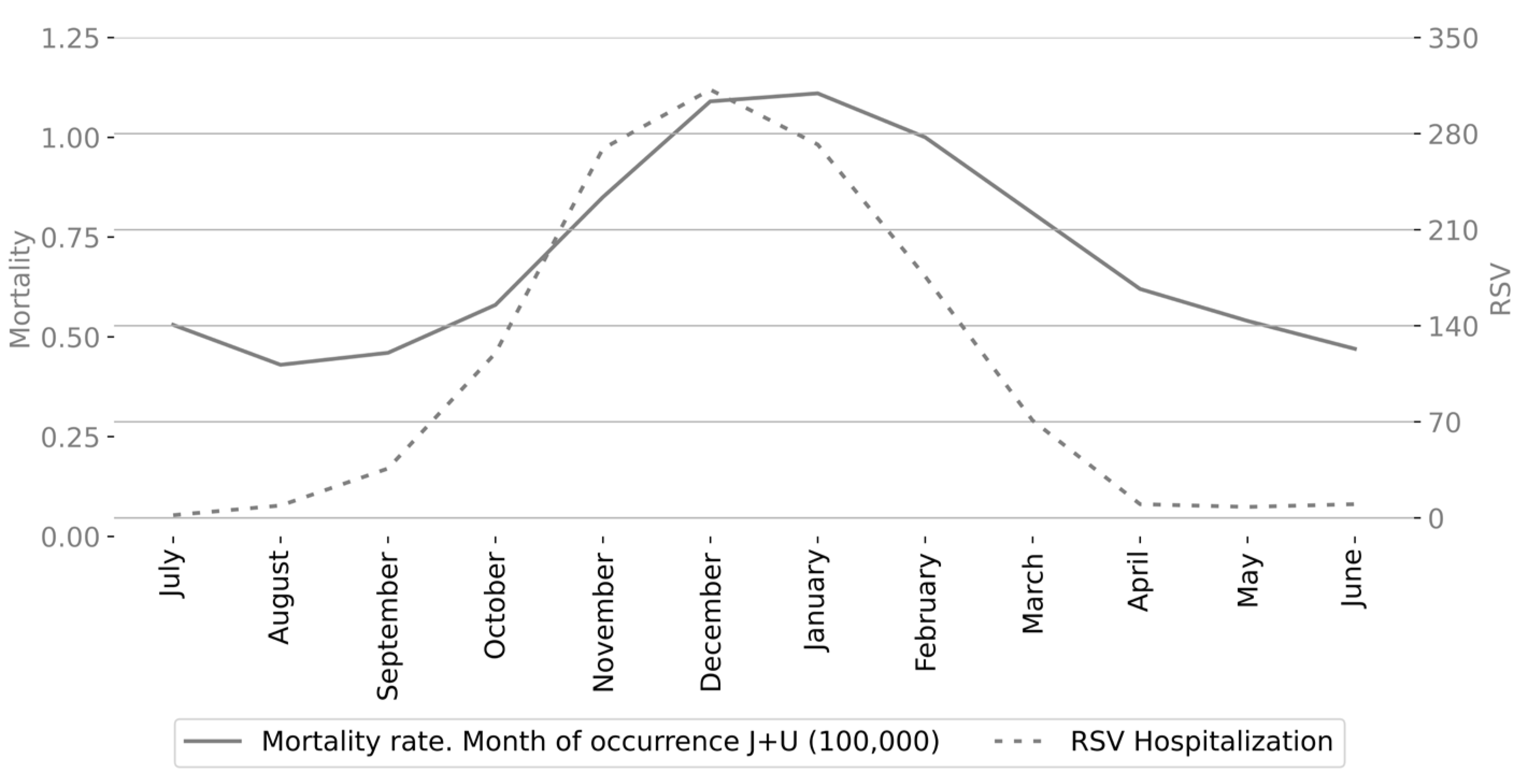

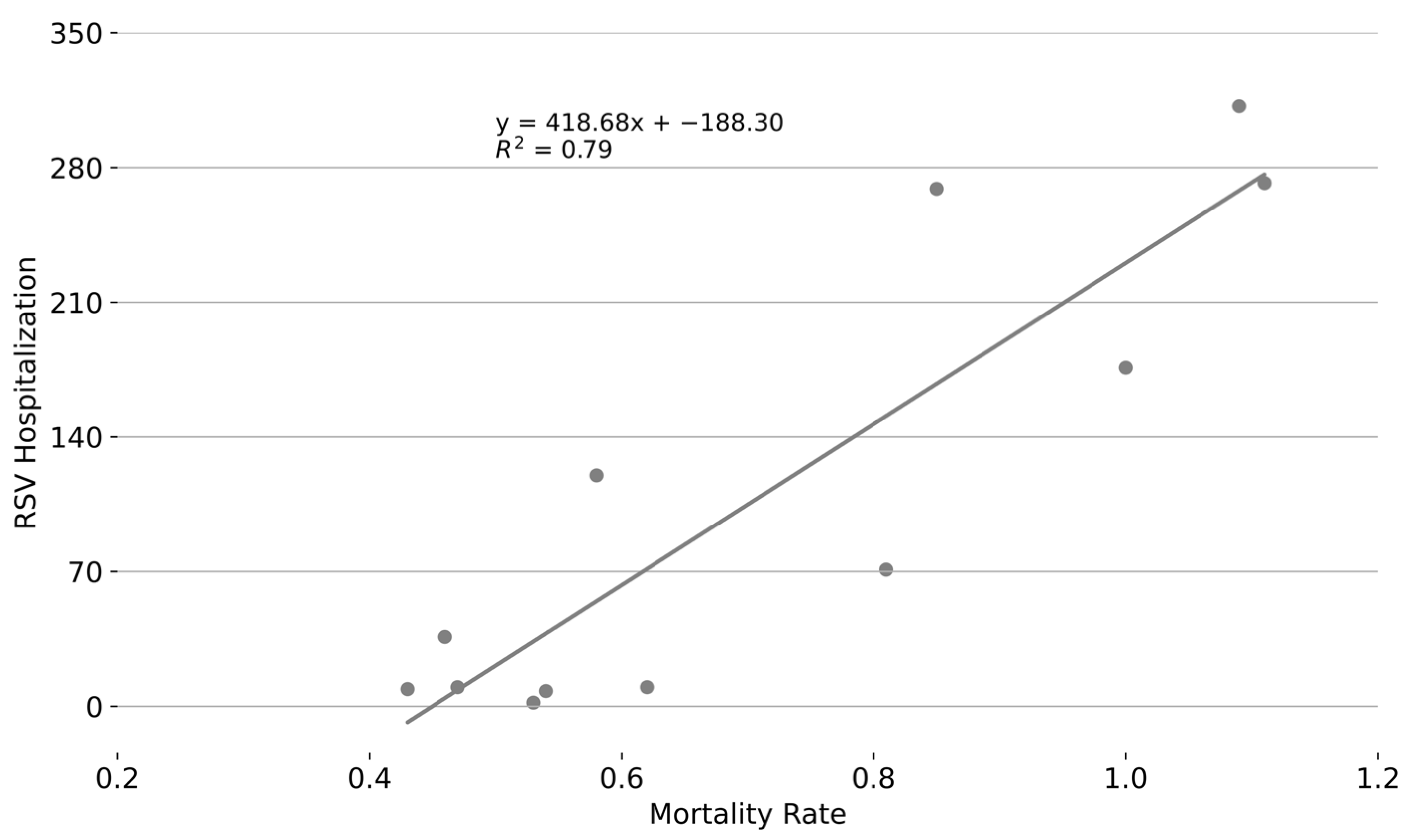

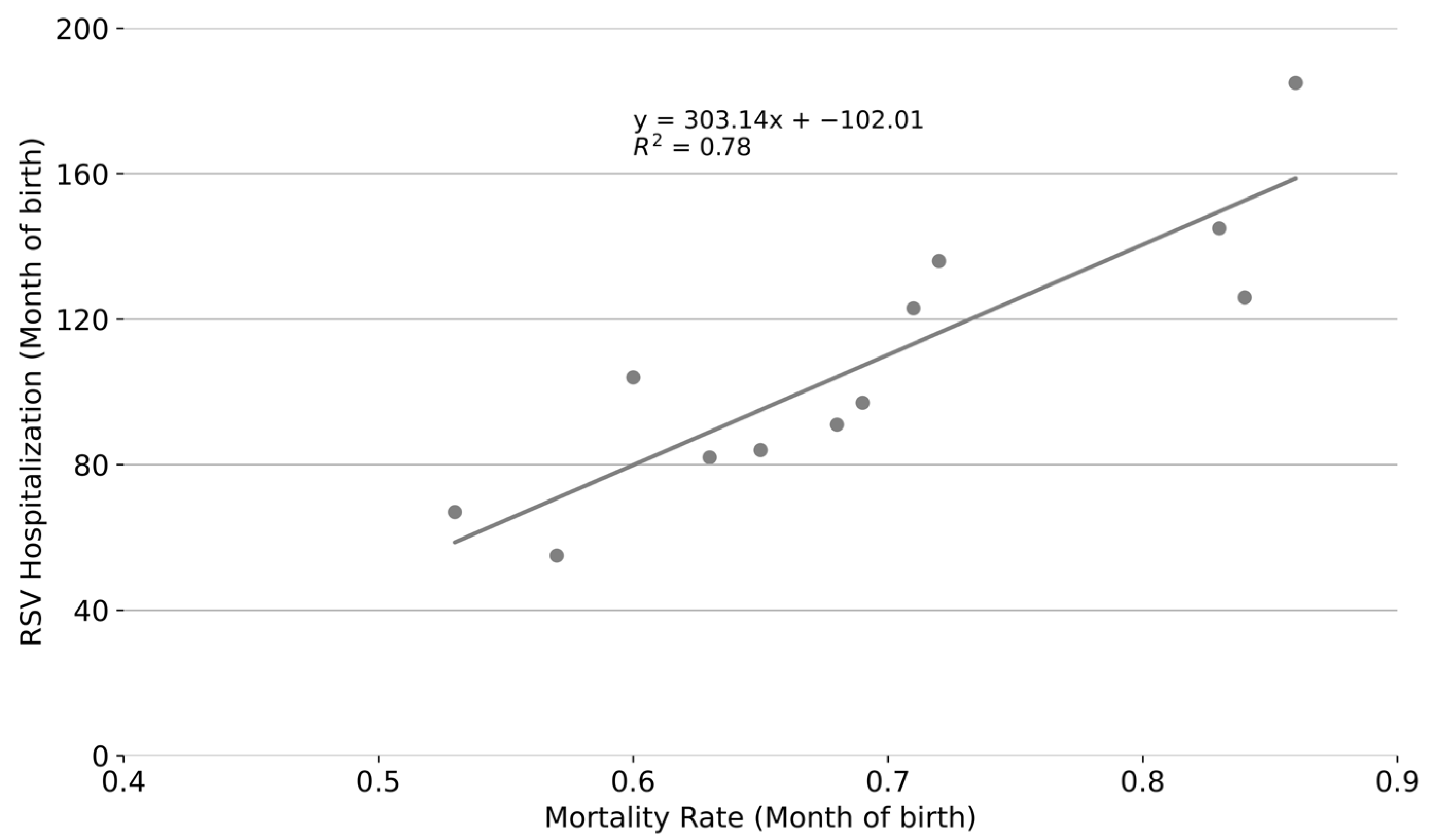

3.2. Correlation Between Seasonal Respiratory-Associated Infant Mortality Rates and RSV Circulation Patterns

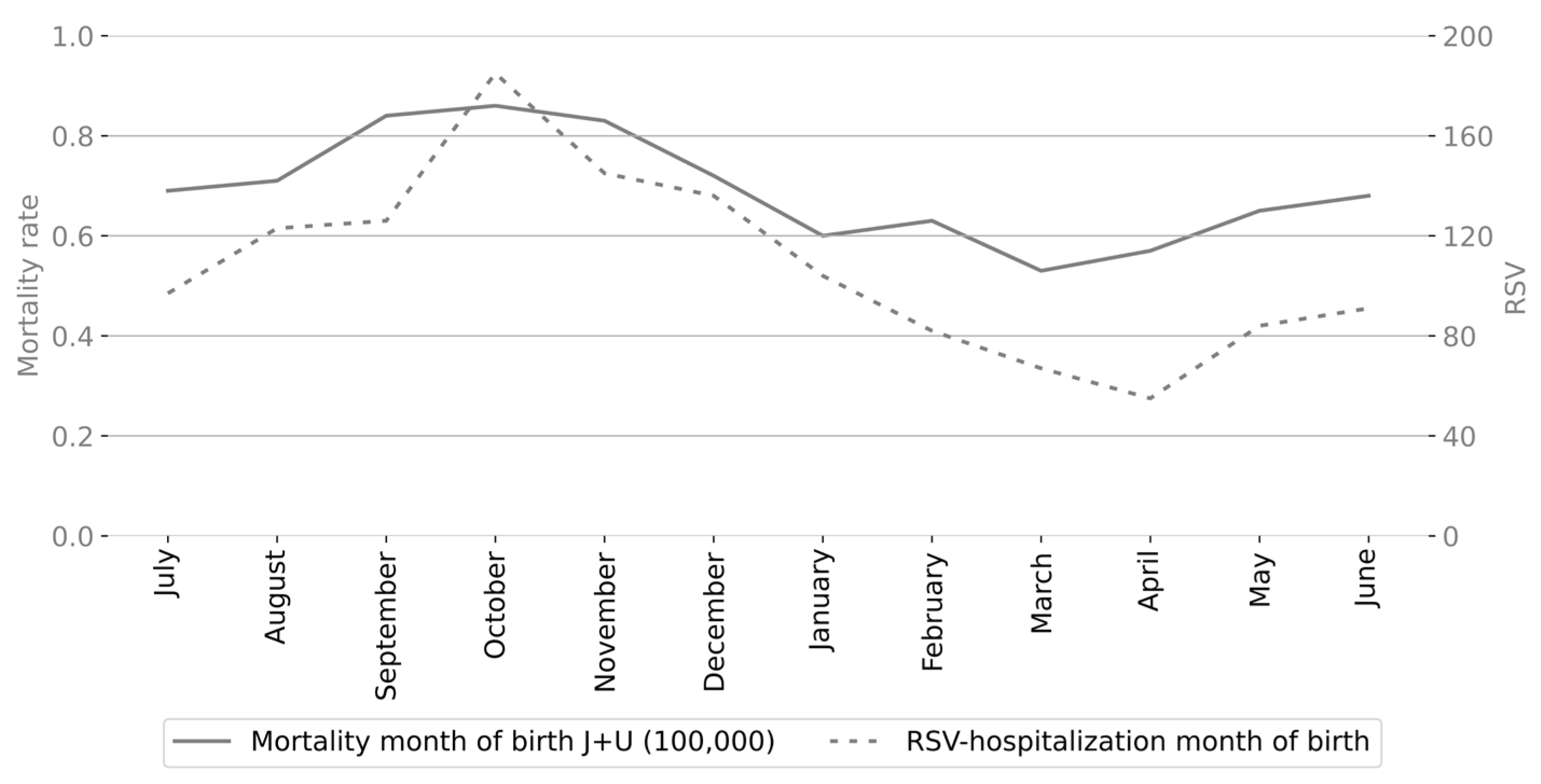

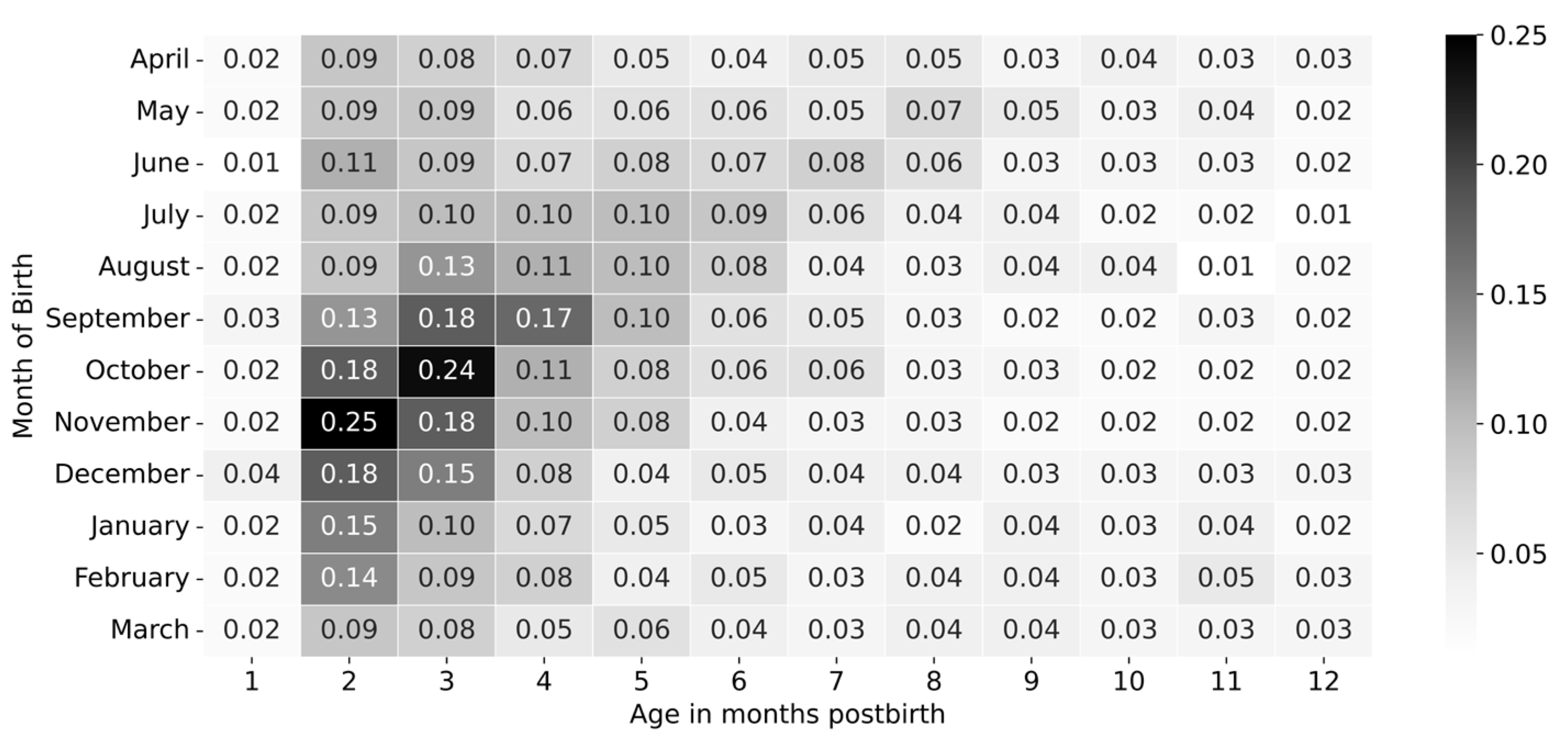

3.3. Age of Death According to Month of Birth

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RSV | Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| INEGI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía |

| ARI | Acute Respiratory Infections |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision |

Appendix A

| State Code | State | Number of Births | Number of Deaths | Respiratory Mortality Rate * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aguascalientes | 154,704 | 80 | 0.52 |

| 2 | Baja California | 318,748 | 90 | 0.66 |

| 3 | Baja California Sur | 71,916 | 36 | 0.50 |

| 4 | Campeche | 94,852 | 58 | 0.61 |

| 5 | Coahuila de Zaragoza | 335,568 | 169 | 0.50 |

| 6 | Colima | 66,398 | 27 | 0.41 |

| 7 | Chiapas | 780,847 | 1093 | 1.40 |

| 8 | Chihuahua | 353,264 | 314 | 0.89 |

| 9 | Ciudad de México | 682,342 | 497 | 0.73 |

| 10 | Durango | 204,847 | 165 | 0.81 |

| 11 | Guanajuato | 669,729 | 429 | 0.64 |

| 12 | Guerrero | 425,281 | 242 | 0.57 |

| 13 | Hidalgo | 283,658 | 151 | 0.53 |

| 14 | Jalisco | 854,794 | 445 | 0.52 |

| 15 | México | 1,615,543 | 902 | 0.56 |

| 16 | Michoacán de Ocampo | 535,308 | 317 | 0.59 |

| 17 | Morelos | 177,192 | 57 | 0.32 |

| 18 | Nayarit | 117,962 | 66 | 0.56 |

| 19 | Nuevo León | 540,412 | 276 | 0.51 |

| 20 | Oaxaca | 447,348 | 349 | 0.78 |

| 21 | Puebla | 741,317 | 766 | 1.03 |

| 22 | Querétaro | 234,345 | 97 | 0.41 |

| 23 | Quintana Roo | 171,679 | 120 | 0.70 |

| 24 | San Luis Potosí | 287,471 | 161 | 0.56 |

| 25 | Sinaloa | 293,436 | 187 | 0.64 |

| 26 | Sonora | 265,796 | 202 | 0.76 |

| 27 | Tabasco | 265,659 | 228 | 0.86 |

| 28 | Tamaulipas | 331,702 | 157 | 0.47 |

| 29 | Tlaxcala | 143,860 | 119 | 0.83 |

| 30 | Veracruz de Ignacio | 739,486 | 570 | 0.77 |

| 31 | Yucatán | 209,705 | 211 | 1.00 |

| 32 | Zacatecas | 188,832 | 105 | 0.56 |

| TOTAL | Mexico (Country) | 12,604,902 | 8805 | 0.70 |

| Region * | States |

|---|---|

| North | Coahuila de Zaragoza, Chihuahua, Durango, San Luis Potosí, Zacatecas |

| Northwest | Baja California, Baja California Sur, Nayarit, Sinaloa, Sonora |

| Northeast | Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas |

| West Central | Aguascalientes, Colima, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacan de Ocampo |

| East Central | Ciudad de Mexico, Hidalgo, Mexico, Morelos, Puebla, Queretaro, Tlaxcala |

| South Central | Tabasco, Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave |

| South | Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca |

| Yucatán Peninsula | Campeche, Quintana Roo, Yucatan |

| Month | Total | Maternal Age (Median) | Paternal Age (Median) | Pregnancy Number (Median) | Singleton Pregnancy | Singleton Pregnancy (%) | Hospital Birth | Hospital Birth (%) | Hospital Birth (% from Specified) † | Single Mother | Single Mother (%) | Single Mother (% from Specified) ‡ | Single, Divorced, Separated, Widow | Single, Divorced, Separated, Widow (%) | Single, Divorced, Separated, Widow (% from Specified) ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July | 1,076,970 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,061,802 | 98.59 | 981,287 | 91.12 | 95.8 | 128,979 | 11.98 | 12.73 | 133,179 | 12.37 | 13.15 |

| August | 1,136,385 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,120,335 | 98.59 | 1,037,757 | 91.32 | 95.97 | 136,162 | 11.98 | 12.73 | 140,630 | 12.38 | 13.15 |

| September | 1,181,923 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,166,299 | 98.68 | 1,079,203 | 91.31 | 95.94 | 139,359 | 11.79 | 12.51 | 144,003 | 12.18 | 12.92 |

| October | 1,153,400 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,137,830 | 98.65 | 1,051,994 | 91.21 | 95.99 | 136,668 | 11.85 | 12.58 | 141,181 | 12.24 | 13 |

| November | 1,056,550 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,043,065 | 98.72 | 960,163 | 90.88 | 95.84 | 127,611 | 12.08 | 12.86 | 131,599 | 12.46 | 13.26 |

| December | 1,067,736 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,053,562 | 98.67 | 968,285 | 90.69 | 95.63 | 128,483 | 12.03 | 12.83 | 132,436 | 12.4 | 13.23 |

| January | 1,019,441 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,005,850 | 98.67 | 926,037 | 90.84 | 95.5 | 124,676 | 12.23 | 13.02 | 128,456 | 12.6 | 13.41 |

| February | 902,558 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 890,437 | 98.66 | 822,025 | 91.08 | 95.62 | 110,659 | 12.26 | 13.01 | 114,130 | 12.65 | 13.42 |

| March | 986,549 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 972,836 | 98.61 | 897,612 | 90.99 | 95.56 | 119,649 | 12.13 | 12.88 | 123,348 | 12.5 | 13.28 |

| April | 994,946 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 981,828 | 98.68 | 904,015 | 90.86 | 95.42 | 117,510 | 11.81 | 12.51 | 121,299 | 12.19 | 12.92 |

| May | 1,024,246 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 1,010,753 | 98.68 | 932,777 | 91.07 | 95.56 | 121,184 | 11.83 | 12.53 | 125,060 | 12.21 | 12.93 |

| June | 1,004,198 | 25 | 28 | 2 | 990,491 | 98.64 | 915,144 | 91.13 | 95.71 | 119,410 | 11.89 | 12.61 | 123,340 | 12.28 | 13.03 |

| Month | Total | Mother Without Any Education Level | Mother Without Any Education Level (%) | Mother Without Any Education Level (% from Specified) † | Mother with Elementary Education | Mother with Elementary Education (%) | Mother with Elementary Education (% from Specified) † | Mother with Elementary Education or No Educational Level | Mother with Elementary Education or No Educational Level (%) | Mother with Elementary Education or No Educational Level (% from Specified) † | Father Without Any Education Level | Father Without Any Education Level (%) | Father Without Any Education Level (% from Specified) ‡ | Father with Elementary Education | Father with Elementary Education (%) | Father with Elementary Education (% from Specified) ‡ | Father with Elementary Education or No Educational Level | Father with Elementary Education or No Educational Level (%) | Father with Elementary Education or No Educational Level (% from Specified) ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July | 1,076,970 | 20,401 | 1.89 | 2.03 | 183,036 | 17.0 | 18.21 | 203,437 | 18.89 | 20.24 | 19,625 | 1.82 | 2.14 | 187,230 | 17.38 | 20.4 | 206,855 | 19.21 | 22.54 |

| August | 1,136,385 | 21,375 | 1.88 | 2.01 | 190,590 | 16.77 | 17.96 | 211,965 | 18.65 | 19.97 | 20,751 | 1.83 | 2.14 | 195,167 | 17.17 | 20.14 | 215,918 | 19.0 | 22.28 |

| September | 1,181,923 | 22,567 | 1.91 | 2.04 | 197,797 | 16.74 | 17.9 | 220,364 | 18.64 | 19.94 | 21,984 | 1.86 | 2.17 | 203,421 | 17.21 | 20.1 | 225,405 | 19.07 | 22.28 |

| October | 1,153,400 | 22,212 | 1.93 | 2.06 | 191,135 | 16.57 | 17.75 | 213,347 | 18.5 | 19.82 | 21,631 | 1.88 | 2.19 | 196,657 | 17.05 | 19.95 | 218,288 | 18.93 | 22.15 |

| November | 1,056,550 | 20,782 | 1.97 | 2.11 | 176,192 | 16.68 | 17.89 | 196,974 | 18.64 | 20.0 | 20,197 | 1.91 | 2.24 | 181,877 | 17.21 | 20.22 | 202,074 | 19.13 | 22.46 |

| December | 1,067,736 | 21,404 | 2.0 | 2.15 | 176,522 | 16.53 | 17.77 | 197,926 | 18.54 | 19.92 | 20,685 | 1.94 | 2.28 | 182,922 | 17.13 | 20.15 | 203,607 | 19.07 | 22.42 |

| January | 1,019,441 | 20,114 | 1.97 | 2.12 | 170,321 | 16.71 | 17.92 | 190,435 | 18.68 | 20.03 | 19,445 | 1.91 | 2.24 | 174,394 | 17.11 | 20.1 | 193,839 | 19.01 | 22.34 |

| February | 902,558 | 17,534 | 1.94 | 2.08 | 150,097 | 16.63 | 17.81 | 167,631 | 18.57 | 19.89 | 17,072 | 1.89 | 2.22 | 154,890 | 17.16 | 20.12 | 171,962 | 19.05 | 22.34 |

| March | 986,549 | 18,890 | 1.91 | 2.05 | 165,146 | 16.74 | 17.93 | 184,036 | 18.65 | 19.98 | 18,172 | 1.84 | 2.16 | 169,659 | 17.2 | 20.19 | 187,831 | 19.04 | 22.35 |

| April | 994,946 | 19,461 | 1.96 | 2.09 | 175,816 | 17.67 | 18.91 | 195,277 | 19.63 | 21.0 | 18,373 | 1.85 | 2.17 | 179,252 | 18.02 | 21.13 | 197,625 | 19.86 | 23.3 |

| May | 1,024,246 | 19,804 | 1.93 | 2.07 | 179,654 | 17.54 | 18.75 | 199,458 | 19.47 | 20.82 | 18,735 | 1.83 | 2.14 | 182,518 | 17.82 | 20.88 | 201,253 | 19.65 | 23.02 |

| June | 1,004,198 | 19,428 | 1.93 | 2.07 | 173,344 | 17.26 | 18.47 | 192,772 | 19.2 | 20.54 | 18,270 | 1.82 | 2.13 | 175,962 | 17.52 | 20.54 | 194,232 | 19.34 | 22.67 |

References

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Blau, D.M.; Caballero, M.T.; Feikin, D.R.; Gill, C.J.; Madhi, S.A.; Omer, S.B.; Simões, E.A.; Campbell, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 2047–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trusinska, D.; Zin, S.T.; Sandoval, E.; Homaira, N.; Shi, T. Risk factors for poor outcomes in children hospitalized with virus-associated acute lower respiratory infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizcarra-Ugalde, S.; Rico-Hernández, M.; Monjarás-Ávila, C.; Bernal-Silva, S.; Garrocho-Rangel, M.E.; Ochoa-Pérez, U.R.; Noyola, D.E. Intensive care unit admission and death rates of infants admitted with respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection in Mexico. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, I.R.S. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics 1998, 102, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, S.B.; Cathie, K.; Flamein, F.; Knuf, M.; Collins, A.M.; Hill, H.C.; Kaiser, F.; Cohen, R.; Pinquier, D.; Felter, C.T.; et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of hospitalizations due to RSV in infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2425–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampmann, B.; Madhi, S.A.; Munjal, I.; Simões, E.A.; Pahud, B.A.; Llapur, C.; Baker, J.; Pérez Marc, G.; Radley, D.; Shittu, E.; et al. Bivalent prefusion F vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHassan, N.O.; Sorbero, M.E.; Hall, C.B.; Stevens, T.P.; Dick, A.W. Cost-effectiveness analysis of palivizumab in premature infants without chronic lung disease. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, M.T.; O’Leary, S.T.; Munoz, F.M.; Ralston, S.L. Palivizumab prophylaxis in infants and young children at increased risk of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics 2023, 152, e2023061803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hodgson, D.; Wang, X.; Atkins, K.E.; Feikin, D.R.; Nair, H. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality and prevention strategy planning for passive immunisation of infants in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanken, M.O.; Paes, B.; Anderson, E.J.; Lanari, M.; Sheridan-Pereira, M.; Buchan, S.; Fullarton, J.R.; Grubb, E.; Notario, G.; Rodgers-Gray, B.S.; et al. Risk scoring tool to predict respiratory syncytial virus hospitalisation in premature infants. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2018, 53, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Batinovic, E.; Milic, P.; Markic, J. The role of birth month in the burden of hospitalisations for acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in Croatia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leija-Martínez, J.J.; Cadena-Mota, S.; González-Ortiz, A.M.; Muñoz-Escalante, J.C.; Mata-Moreno, G.; Hernández-Sánchez, P.G.; Vega-Morúa, M.; Noyola, D.E. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Other Respiratory Viruses in Hospitalized Infants During the 2023–2024 Winter Season in Mexico. Viruses 2024, 16, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda-Romo, S.; Comas-García, A.; García-Sepúlveda, C.A.; Hernández-Salinas, A.E.; Piña Ramírez, M.; Noyola, D.E. Effect of an immunization program on seasonal influenza hospitalizations in Mexican children. Vaccine 2010, 28, 2550–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Rivera, B.; Saldaña-Ahuactzi, Z.; Parra-Ortega, I.; Flores-Alanis, A.; Carbajal-Franco, E.; Cruz-Rangel, A.; Galaviz-Hernandez, S.; Romero-Navarro, B.; de la Rosa-Zamboni, D.; Salazar-Garcia, M.; et al. Frequency of respiratory virus-associated infection among children and adolescents from a tertiary-care hospital in Mexico City. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Barreto, D.; Espinosa-Monteros, L.E.; López-Enríquez, C.; Jiménez-Rojas, V.; Rodríguez-Suárez, R. Invasive pneumococcal disease in a third level pediatric hospital in Mexico City: Epidemiology and mortality risk factors. Salud Pública De México 2010, 52, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aquino-Andrade, A.; Martínez-Leyva, G.; Mérida-Vieyra, J.; Saltigeral, P.; Lara, A.; Domínguez, W.; de la Puente, S.G.; De Colsa, A. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction–Based Detection of Bordetella pertussis in Mexican Infants and Their Contacts: A 3-Year Multicenter Study. J. Pediatr. 2017, 188, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamiño-Arroyo, A.E.; Moreno-Espinosa, S.; Llamosas-Gallardo, B.; Ortiz-Hernández, A.A.; Guerrero, M.L.; Galindo-Fraga, A.; Galán-Herrera, J.F.; Prado-Galbarro, F.J.; Beigel, J.H.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus infections among children and adults in Mexico. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2017, 11, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Chew, R.M.; García-León, M.L.; Noyola, D.E.; Gonzalez, L.F.P.; Meza, J.G.; Vilaseñor-Sierra, A.; Martinez-Aguilar, G.; Rivera-Nuñez, V.H.; Newton-Sánchez, O.A.; Firo-Reyes, V.; et al. Respiratory viruses detected in Mexican children younger than 5 years old with community-acquired pneumonia: A national multicenter study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 62, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). Natalidad—Datos Abiertos [Birth Statistics–Open Data]. 2024. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/natalidad/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). Estadísticas de Defunciones Registradas-Datos Abiertos [Registered Death Statistics–Open Data]. 2024. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/edr/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Delgadillo Macías, J.; Torres Torres, F. Estudios regionales en México: Aproximaciones a las obras y sus autores [Regional Studies in Mexico: Approaches to the Works and Their Authors]; Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, UNAM: Ciudad de México, México, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ortiz, A.M.; Bernal-Silva, S.; Comas-García, A.; Vega-Morúa, M.; Garrocho-Rangel, M.E.; Noyola, D.E. Severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in hospitalized children. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Moreno, G.; Bernal-Silva, S.; García-Sepúlveda, C.A.; González-Ortíz, A.M.; Ochoa-Pérez, U.R.; Medina-Serpa, A.U.; Pérez-González, L.F.; Noyola, D.E. Population-based Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus Hospitalizations and In-hospital Mortality Rates Among Mexican Children Less Than Five Years of Age. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Coates, M.M.; Coggeshall, M.; Dandona, L.; Diallo, K.; Franca, E.B.; Fraser, M.; Fullman, N.; Gething, P.W.; et al. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1725–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.; Kim, J.S. Regional Disparities in the Infant Mortality Rate in Korea Between 2001 and 2021. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L. Indigenous infant mortality by age and season of birth, 1800–1899: Did season of birth affect children’s chances for survival? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastman, P.R. Infant mortality in relation to month of birth. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 1945, 35, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantenberg, J.R.; van Aalst, R.; Bhuma, M.R.; Limone, B.; Diakun, D.; Smith, D.M.; Nelson, C.B.; Bengtson, A.M.; Chaves, S.S.; La Via, W.V.; et al. Risk Analysis of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Among Infants in the United States by Birth Month. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2024, 13, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, H.; Suh, M.; Jiang, X.; Movva, N.; Bylsma, L.C.; Fryzek, J.P.; Nelson, C.B. Mortality associated with respiratory syncytial virus, bronchiolitis, and influenza among infants in the United States: A birth cohort study from 1999 to 2018. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, S246–S254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV Vaccine Guidance for Pregnant Women. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/hcp/vaccine-clinical-guidance/pregnant-people.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV Immunization Guidance for Infants and Young Children. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/hcp/vaccine-clinical-guidance/infants-young-children.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Daniels, D. A review of respiratory syncytial virus epidemiology among children: Linking effective prevention to vulnerable populations. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2024, 13, S131–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, J.E.; Özaltin, E.; Canning, D. The association of maternal age with infant mortality, child anthropometric failure, diarrhoea and anaemia for first births: Evidence from 55 low-and middle-income countries. BMJ Open 2011, 1, e000226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; O’brien, K.L.; Madhi, S.A.; Widdowson, M.A.; Byass, P.; Omer, S.B.; Abbas, Q.; Ali, A.; Amu, A.; et al. Global burden of respiratory infections associated with seasonal influenza in children under 5 years in 2018: A systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e497–e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Deloria-Knoll, M.; Madhi, S.A.; Cohen, C.; Ali, A.; Basnet, S.; Bassat, Q.; Brooks, W.A.; Chittaganpitch, M.; et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infection associated with human metapneumovirus in children under 5 years in 2018: A systematic review and modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e33–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Winn, A.; Parikh, R.; Jones, J.M.; McMorrow, M.; Prill, M.M.; Silk, B.J.; Scobie, H.M.; Hall, A.J. Seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus—United States, 2017–2023. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ICD-10 Codes | Diagnoses | Number of Deaths (n = 8805) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| J00X-J069 | Upper respiratory tract infections | 199 | 2.26 |

| J09X-J118 | Influenza | 93 | 1.06 |

| J120-J129 | Viral pneumonia (including J12.1: RSV pneumonia) | 54 | 0.61 |

| J13X-J159 | Bacterial pneumonia | 282 | 3.2 |

| J168-J189 | Pneumonia by other agents and non-specified | 4932 | 56.01 |

| J200-J219 | Bronchitis and bronchiolitis (including J21.0: acute bronchiolitis due to RSV) | 545 | 6.19 |

| J22X | Acute lower respiratory tract infection, non-specified | 338 | 3.84 |

| J304-J348 | Rhinitis and other nasal disorders | 8 | 0.09 |

| J380-J399 | Laryngeal, pharyngeal and other upper respiratory tract disorders | 30 | 0.34 |

| J42X-J449 | Bronchitis, emphysema, and other chronic lung diseases | 74 | 0.84 |

| J450-J46X | Asthma | 119 | 1.35 |

| J677-J849 | Pneumonitis associated with diverse conditions (including air humidifier, non-specified organic dusts, oils, among others) and other lung alveoli and interstitial disorders | 624 | 7.09 |

| J852-J948 | Pulmonary abscess, pneumothorax and other pleural space disorders | 95 | 1.08 |

| J960-J969 | Acute and chronic respiratory failure | 171 | 1.94 |

| J980-J989 | Diverse tracheal, bronchial, and lung disorders | 1153 | 13.09 |

| U071-U072 | COVID-19 1 | 88 | 1 |

| Month | East-Central | West-Central | South-Central | Northeast | Northwest | North | South | Yucatán Peninsula | National |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 0.78 | 0.69 |

| August | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| September | 0.80 | 0.73 | 1.02 | 0.52 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.84 |

| October | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 1.22 | 0.86 |

| November | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.83 |

| December | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.98 | 0.60 | 0.72 |

| January | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.83 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.59 | 0.95 | 0.73 | 0.60 |

| February | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 1.11 | 0.84 | 0.63 |

| March | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.62 | 1.08 | 0.62 | 0.53 |

| April | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.96 | 0.45 | 0.57 |

| May | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 1.21 | 0.77 | 0.65 |

| June | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.68 |

| Yearly Avg | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 0.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milán, A.; Cuevas-Tello, J.C.; Noyola, D.E. Respiratory Infant Mortality Rate by Month of Birth in Mexico. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040083

Milán A, Cuevas-Tello JC, Noyola DE. Respiratory Infant Mortality Rate by Month of Birth in Mexico. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(4):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040083

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilán, Alessandro, Juan C. Cuevas-Tello, and Daniel E. Noyola. 2025. "Respiratory Infant Mortality Rate by Month of Birth in Mexico" Epidemiologia 6, no. 4: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040083

APA StyleMilán, A., Cuevas-Tello, J. C., & Noyola, D. E. (2025). Respiratory Infant Mortality Rate by Month of Birth in Mexico. Epidemiologia, 6(4), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040083