Adult Food Allergy Is an Under-Recognized Health Problem in Northwestern Mexico: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Case Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants, Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence Estimates

3.3. Prevalence Estimates of Food Allergies for Specific Foods

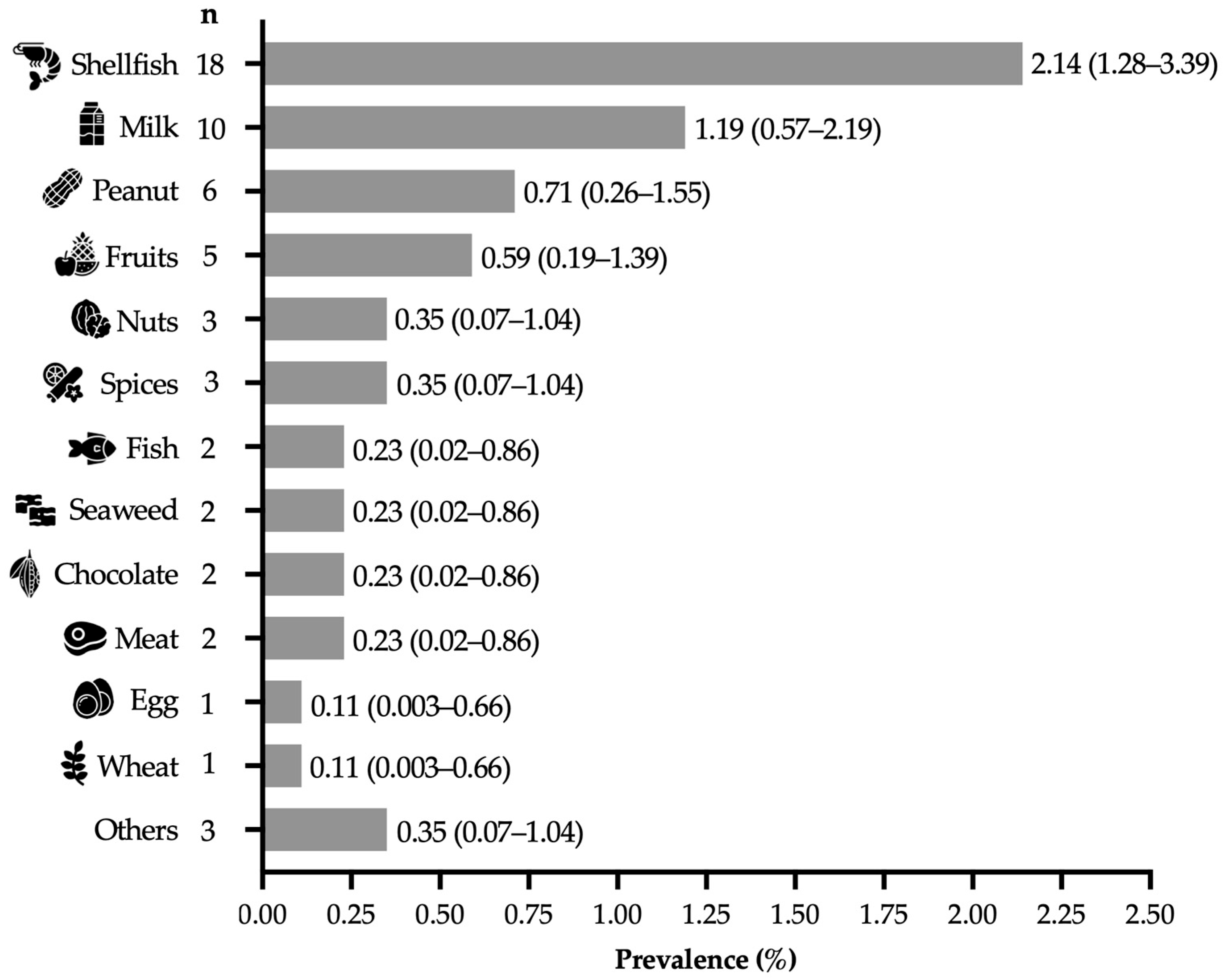

3.4. Clinical Characteristics and Context of Allergic Reactions

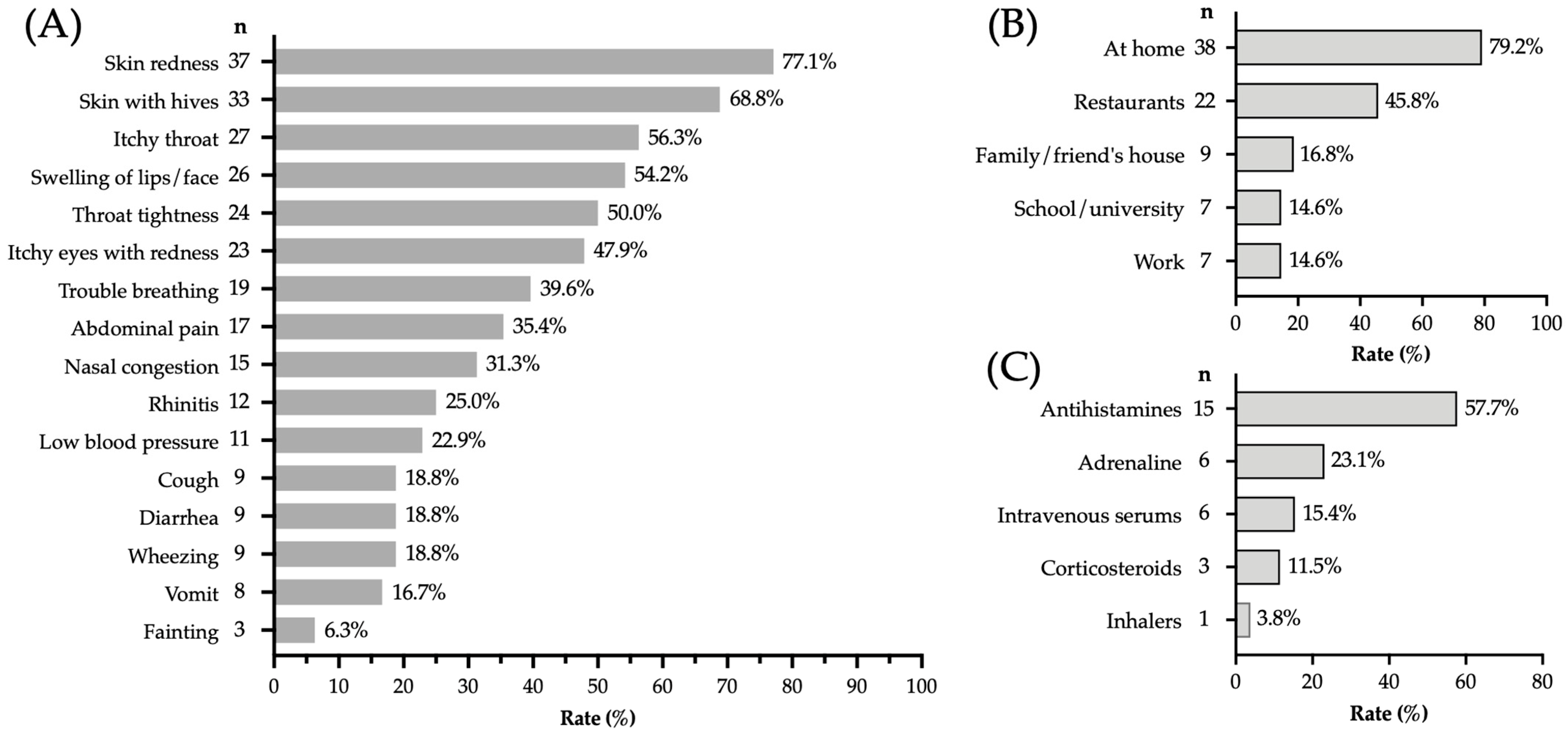

3.5. Characteristics of Physician-Diagnosed FA Cases

3.6. Risk Factors Associated with Immediate-Type FA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| FA | Food allergy |

| OR | Odds ratio |

References

- Anvari, S.; Miller, J.; Yeh, C.-Y.; Davis, C.M. IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 57, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Cruz, S. Alergias alimentarias: Importancia del control de alérgenos en alimentos. Nutr. Clin. Diet. Hosp. 2018, 38, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, E.G.; Kwan, M.; Virkud, Y.V.; Iweala, O.I. Management of Food Allergies and Food-Related Anaphylaxis. JAMA 2024, 331, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Armendáriz, L.Á.; Nava-Hernández, M.P.; Amador-Robles, M.; Rosales-González, M.; Meza-Velázquez, R. Mecanismos fisiopatológicos de alergia a alimentos. Alerg. Asma Inmunol. Pediátr. 2021, 30, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ontiveros, N.; Gallardo, J.A.-L.; Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G.; Beltrán-Cárdenas, C.E.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Mora-Melgem, J.A.; Granda-Restrepo, D.M.; Rodríguez-Bellegarrigue, C.I.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.d.J.; Cárdenas-Torres, F.I.; et al. Characteristics of Allergen Labelling and Precautionary Allergen Labelling in Packaged Food Products Available in Latin America. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea-Tobarra, M.M.; Blázquez-Abellán, G. Alergias Alimentarias: Revisión de La Legislación Correspondiente a La Gestión y al Etiquetado de Alérgenos. Ars Pharm. Internet 2023, 64, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, A.T.; Ahlstedt, S.; Golding, M.A.; Protudjer, J.L.P. The Economic Burden of Food Allergy: What We Know and What We Need to Learn. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2022, 9, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.M.; Jiang, J.; Gupta, R.S. Epidemiology and Burden of Food Allergy. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungles, K.N.; Jungles, K.M.; Greenfield, L.; Mahdavinia, M. The Infant Microbiome and Its Impact on Development of Food Allergy. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2021, 41, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.A.; Burney, P.G.J.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Barreales, L.; Clausen, M.; Dubakiene, R.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Fritsche, P.; Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz, M.; et al. Food Allergy in Adults: Substantial Variation in Prevalence and Causative Foods Across Europe. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1920–1928.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Warren, C.M.; Smith, B.M.; Jiang, J.; Blumenstock, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Schleimer, R.P.; Nadeau, K.C. Prevalence and Severity of Food Allergies Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e185630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Ramírez-Torres, G.I.; Terán-Cabanillas, E.; Gracia-Valenzuela, M.H.; Arvizu-Flores, A.A.; Sánchez-Cárdenas, C.A.; Mora-Melgem, J.A.; Valdez-Zavala, L.; Cárdenas-Torres, F.I.; et al. Prevalence of Parent-Reported Food Allergy in a Mexican Pre-School Population. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedolla-Barajas, M.; Morales-Romero, J.; Sánchez-Magallón, R.; Valdez-Soto, J.A.; Bedolla-Pulido, T.R.; Meza-López, C. Food Allergy among Mexican Infants and Preschoolers: Prevalence and Associated Factors. World J. Pediatr. 2023, 19, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontiveros, N.; Valdez-Meza, E.E.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.J.; Canizalez-Román, A.; Borzutzky, A.; Cabrera-Chávez, F. Parent-Reported Prevalence of Food Allergy in Mexican Schoolchildren: A Population-Based Study. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2016, 44, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedolla-Pulido, T.; Bedolla-Barajas, M.; Morales-Romero, J.; Bedolla-Pulido, T.; Domínguez-García, M.; Hernández-Colín, D.; Flores-Merino, M. Self-Reported Hypersensitivity and Allergy to Foods amongst Mexican Adolescents: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2019, 47, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Segura, L.T.; Figueroa Pérez, E.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Siepmann, T.; Larenas-Linnemann, D. Food Allergen Sensitization Patterns in a Large Allergic Population in Mexico. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2020, 48, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedolla-Barajas, M.; Bedolla-Pulido, T.R.; Camacho-Peña, A.S.; González-García, E.; Morales-Romero, J. Food Hypersensitivity in Mexican Adults at 18 to 50 Years of Age: A Questionnaire Survey. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2014, 6, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Romero, J.; Aguilar-Panduro, M.; Bedolla-Pulido, T.R.; Hernández-Colín, D.D.; Nuñez-Nuñez, M.E.; Bedolla-Barajas, M. More than Ten Years without Changes in the Prevalence of Adverse Food Reactions among Mexican Adults: Comparison of Two Cross-Sectional Surveys. Asia Pac. Allergy 2025, 15, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Fernández, C.; Maya-Hernández, R.L.; Flores-Merino, M.V.; del Socorro Romero-Figueroa, M.; Bedolla-Barajas, M.; García, M.V.D. Self-Reported Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Food Hypersensitivity in Mexican Young Adults. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 523–527.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Bachiloglu, R.; Ivanovic-Zuvic, D.; Álvarez, J.; Linn, K.; Thöne, N.; de los Ángeles Paul, M.; Borzutzky, A. Prevalence of Parent-Reported Immediate Hypersensitivity Food Allergy in Chilean School-Aged Children. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2014, 42, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Chávez, F.; Rodríguez-Bellegarrigue, C.I.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Lopez-Gallardo, J.A.; Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.d.J.; Castro-Acosta, M.L.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; Gracia-Valenzuela, M.H.; Ontiveros, N. Food Allergy Prevalence in Salvadoran Schoolchildren Estimated by Parent-Report. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicherer, S.H.; Muñoz-Furlong, A.; Burks, A.W.; Sampson, H.A. Prevalence of Peanut and Tree Nut Allergy in the US Determined by a Random Digit Dial Telephone Survey. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicherer, S.H.; Burks, A.W.; Sampson, H.A. Clinical Features of Acute Allergic Reactions to Peanut and Tree Nuts in Children. Pediatrics 1998, 102, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, F.E.R.; Ardusso, L.R.F.; Bilò, M.B.; El-Gamal, Y.M.; Ledford, D.K.; Ring, J.; Sanchez-Borges, M.; Senna, G.E.; Sheikh, A.; Thong, B.Y.; et al. World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Guidelines: Summary. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 587–593.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, C.M.; Sehgal, S.; Sicherer, S.H.; Gupta, R.S. Epidemiology and the Growing Epidemic of Food Allergy in Children and Adults across the Globe. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2024, 24, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Sánchez, A. Epidemiology of Food Allergy in Latin America. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2015, 43, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, I.; Almulhem, N.; Santos, A.F. Feast for Thought: A Comprehensive Review of Food Allergy 2021–2023. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 153, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.A.; Silva, A.F.M.; Ribeiro, Â.C.; Silva, A.O.; Vieira, F.A.; Segundo, G.R. Adult Food Allergy Prevalence: Reducing Questionnaire Bias. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 171, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrugo, J.; Hernández, L.; Villalba, V. Prevalence of Self-Reported Food Allergy in Cartagena (Colombia) Population. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2008, 36, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G.; de los Ángeles Sabaté, M.; Wagner, I.; Dezar, G.V.A.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.d.J.; Ontiveros, N.; Cabrera-Chávez, F.; Cárdenas-Torres, F.I. Food Allergy in Argentinian Schoolchildren: A Survey-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Rev. Médica Univ. Autónoma Sinaloa REVMEDUAS 2022, 10, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Cárdenas, C.E.; Granda-Restrepo, D.M.; Franco-Aguilar, A.; Lopez-Teros, V.; Arvizu-Flores, A.A.; Cárdenas-Torres, F.I.; Ontiveros, N.; Cabrera-Chávez, F.; Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G. Prevalence of Food-Hypersensitivity and Food-Dependent Anaphylaxis in Colombian Schoolchildren by Parent-Report. Medicina 2021, 57, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamdar, T.A.; Peterson, S.; Lau, C.H.; Saltoun, C.A.; Gupta, R.S.; Bryce, P.J. Prevalence and Characteristics of Adult-Onset Food Allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2015, 3, 114–115.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachshon, L.; Schwartz, N.; Elizur, A.; Schon, Y.; Cheryomukhin, M.; Katz, Y.; Goldberg, M.R. The Prevalence of Food Allergy in Young Israeli Adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2782–2789.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1 NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010, Especificaciones Generales de Etiquetado Para Alimentos y Bebidas No Alcohólicas Preenvasados-Información Comercial y Sanitaria. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4010/seeco11_C/seeco11_C.htm (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Unión Europea. Reglamento (UE) nº 1169/2011 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 25 de octubre de 2011 sobre la información alimentaria facilitada al consumidor y por el que se modifican los Reglamentos (CE) nº 1924/2006 y (CE) nº 1925/2006 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, y por el que se derogan la Directiva 87/250/CEE de la Comisión, la Directiva 90/496/CEE del Consejo, la Directiva 1999/10/CE de la Comisión, la Directiva 2000/13/CE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, las Directivas 2002/67/CE de la Comisión. D. Of. Unión Eur. 2011, 304, 18–63. [Google Scholar]

- Larenas-Linnemann, D.; Luna-Pech, J.A.; Rodríguez-Pérez, N.; Rodríguez-González, M.; Arias-Cruz, A.; Blandón-Vijil, M.V.; Costa-Domínguez, M.d.C.; Río-Navarro, B.E.D.; Estrada-Cardona, A.; Navarrete-Rodríguez, E.M.; et al. GUIMIT 2019, Guía Mexicana de Inmunoterapia. Guía de diagnóstico de alergia mediada por IgE e inmunoterapia aplicando el método ADAPTE. Rev. Alerg. México 2019, 66, 1–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baseggio Conrado, A.; Patel, N.; Turner, P.J. Global Patterns in Anaphylaxis Due to Specific Foods: A Systematic Review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1515–1525.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, L.K.; Worm, M.; Ebisawa, M.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Senna, G.; Fineman, S.; Geller, M.; Gonzalez-Estrada, A.; Campbell, D.E.; Leung, A.; et al. Global Disparities in Availability of Epinephrine Auto-Injectors. World Allergy Organ. J. 2023, 16, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoos, A.-M.M. Atopic Diseases—Diagnostics, Mechanisms, and Exposures. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 35, e14198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Sánchez, A. Epidemiologic Studies about Food Allergy and Food Sensitization in Tropical Countries. Results and Limitations. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2019, 47, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Average age in years (range) | 34.4 (18–93) | |

| Sex | Female | 429 (51.43%) |

| Male | 405 (48.56%) | |

| History of allergic diseases other than FA | ||

| Allergic rhinitis | 123 (14.74%) | |

| Drug allergy | 117 (14.02%) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 98 (11.75%) | |

| Chronic Urticaria | 91(10.91%) | |

| Conjunctivitis | 68 (8.15%) | |

| Asthma | 59 (7.07%) | |

| Animal allergy | 53 (6.35%) | |

| Insect sting allergy | 39 (4.67%) | |

| Anaphylaxis | 23 (3.11%) | |

| Assessment | Number of Cases | Prevalence % (95% CI) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 834) | Men (n = 405) | Women (n = 429) | |||

| Adverse food reactions | 120 | 14.38 (12.08–16.96) | 12.59 (9.52–16.22) | 16.08 (12.73–19.91) | 0.167 |

| Physician-diagnosed FA, ever | 41 | 4.91 (3.55–6.61) | 2.46 (1.19–4.49) | 7.22 (4.96–10.1) | 0.001 |

| Immediate-type FA, ever | 64 | 7.67 (5.96–9.69) | 6.17 (4.03–8.97) | 9.09 (6.54–12.22) | 0.12 |

| Immediate-type FA, current | 48 | 5.75 (4.27–7.49) | 4.44 (2.65–6.93) | 6.99 (4.76–9.83) | 0.117 |

| Food-induced anaphylaxis | 23 | 2.75 (1.75–4.10) | 1.72 (0.69–3.52) | 3.72 (2.14–5.98) | 0.081 |

| Allergic Disease | Immediate Type FA, Ever | No FA | p | Odds Ratio (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 64) | (n = 770) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Personal history | ||||

| Anaphylaxis | 8 (12.5) | 18 (2.33) | 0.0004 | 5.96 (2.59–13.50) |

| Animal allergy | 15 (23.43) | 38 (4.93) | <0.0001 | 5.89 (3.10–11.18) |

| Conjunctivitis | 15 (23.43) | 53 (6.88) | <0.0001 | 4.14 (2.20–7.81) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 22 (34.37) | 101 (13.11) | <0.0001 | 3.47 (1.95–5.93) |

| Urticaria | 15 (18.75) | 76 (9.87) | 0.0026 | 2.79 (1.44–5.07) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 15 (23.43) | 83 (10.77) | 0.007 | 2.53 (1.32–4.75) |

| Drug allergy | 17 (26.56) | 100 (12.98) | 0.0075 | 2.42 (1.37–4.34) |

| Insect sting allergy | 6 (9.37) | 33 (4.28) | 0.1115 | 2.31 (0.98–5.45) |

| Asthma | 8 (12.5) | 51 (6.62) | 0.1205 | 2.01 (0.94–4.46) |

| Paternal history | ||||

| Insect sting allergy | 2 (3.12) | 3 (0.38) | 0.049 | 8.24 (1.43–40.78) |

| Conjunctivitis | 3 (4.68) | 9 (1.16) | 0.057 | 4.15 (1.18–15.67) |

| Asthma | 5 (7.81) | 21 (2.72) | 0.042 | 3.023 (1.20–7.88) |

| Food allergy | 6 (9.37) | 29 (3.76) | 0.044 | 2.64 (1.10–6.39) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 4 (6.25) | 24 (3.11) | 0.263 | 2.07 (0.75–5.82) |

| Anaphylaxis | 1 (1.56) | 6 (0.77) | 0.429 | 2.02 (0.17–12.58) |

| Drug allergy | 4 (6.25) | 33 (4.28) | 0.519 | 1.48 (0.54–4.27) |

| Animal allergy | 1 (1.56) | 9 (1.16) | 0.552 | 1.34 (0.12–8.35) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (1.56) | 13 (1.68) | >0.99 | 0.92 (0.08–5.89) |

| Maternal history | ||||

| Food allergy | 6 (9.37) | 23 (2.98) | 0.018 | 3.36 (1.37–8.57) |

| Anaphylaxis | 2 (3.12) | 10 (1.29) | 0.233 | 2.45 (0.52–10.91) |

| Asthma | 4 (6.25) | 28 (3.63) | 0.299 | 1.76 (0.64–4.81) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 3 (4.68) | 28 (3.63) | 0.725 | 1.3 (0.40–4.15) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (1.56) | 10 (1.29) | 0.586 | 1.2 (0.10–7.16) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 3 (4.68) | 34 (4.41) | 0.757 | 1.06 (0.33–3.28) |

| Insect sting allergy | 1 (1.56) | 12 (1.55) | >0.999 | 1 (0.09–5.58) |

| Drug allergy | 3 (4.68) | 45 (5.84) | >0.999 | 0.79 (0.25–2.36) |

| Animal allergy | 0 | 19 (2.46) | 0.388 | – |

| Sibling History | ||||

| Conjunctivitis | 5 (7.81) | 15 (1.94) | 0.014 | 4.26 (1.65–11.20) |

| Food allergy | 9 (14.06) | 33 (4.28) | 0.003 | 3.65 (1.63–7.84) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 7 (10.93) | 26 (3.37) | 0.009 | 3.51(1.37–8.15) |

| Drug allergy | 10 (15.62) | 48 (6.23) | 0.009 | 2.78 (1.36–5.73) |

| Anaphylaxis | 2 (3.12) | 9 (1.16) | 0.204 | 2.72 (0.57–10.70) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 10 (15.62) | 54 (7.01) | 0.023 | 2.45 (1.20–4.97) |

| Insect sting allergy | 4 (6.25) | 23 (2.98) | 0.145 | 2.16 (0.78–6.14) |

| Animal allergy | 6 (9.37) | 37 (4.8) | 0.132 | 2.04 (0.87–5.07) |

| Asthma | 4 (6.25) | 47 (6.10) | >0.999 | 1.02 (0.38–2.80) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vizcarra-Olguin, L.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.d.J.; Velásquez-Rodríguez, J.M.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Barrón-Cabrera, E.M.; Gutiérrez-Arzapalo, P.Y.; Salas-López, F.; Ontiveros, N.; Arámburo-Gálvez, J.G. Adult Food Allergy Is an Under-Recognized Health Problem in Northwestern Mexico: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Epidemiologia 2025, 6, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040085

Vizcarra-Olguin L, Vergara-Jiménez MdJ, Velásquez-Rodríguez JM, Figueroa-Salcido OG, Barrón-Cabrera EM, Gutiérrez-Arzapalo PY, Salas-López F, Ontiveros N, Arámburo-Gálvez JG. Adult Food Allergy Is an Under-Recognized Health Problem in Northwestern Mexico: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Epidemiologia. 2025; 6(4):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleVizcarra-Olguin, Lizbeth, Marcela de Jesús Vergara-Jiménez, Juancarlos Manuel Velásquez-Rodríguez, Oscar Gerardo Figueroa-Salcido, Elisa María Barrón-Cabrera, Perla Y. Gutiérrez-Arzapalo, Fernando Salas-López, Noé Ontiveros, and Jesús Gilberto Arámburo-Gálvez. 2025. "Adult Food Allergy Is an Under-Recognized Health Problem in Northwestern Mexico: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey" Epidemiologia 6, no. 4: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040085

APA StyleVizcarra-Olguin, L., Vergara-Jiménez, M. d. J., Velásquez-Rodríguez, J. M., Figueroa-Salcido, O. G., Barrón-Cabrera, E. M., Gutiérrez-Arzapalo, P. Y., Salas-López, F., Ontiveros, N., & Arámburo-Gálvez, J. G. (2025). Adult Food Allergy Is an Under-Recognized Health Problem in Northwestern Mexico: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Epidemiologia, 6(4), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia6040085