Reliability of Fine-Pitch Cu-Microbumps for 3D Heterogeneous Integration: Effect of Solder, Pitch Scaling and Substrate Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Finite Element Modeling and Scheme Design

2.1. Constitutive Equations

2.2. Finite Element Analysis

2.3. Lifetime Prediction Models

2.4. IMC Growth Kinetics

3. Effect of Cu-Microbump Pitch on Thermal Cycling Behavior

3.1. Failure Mode Analysis

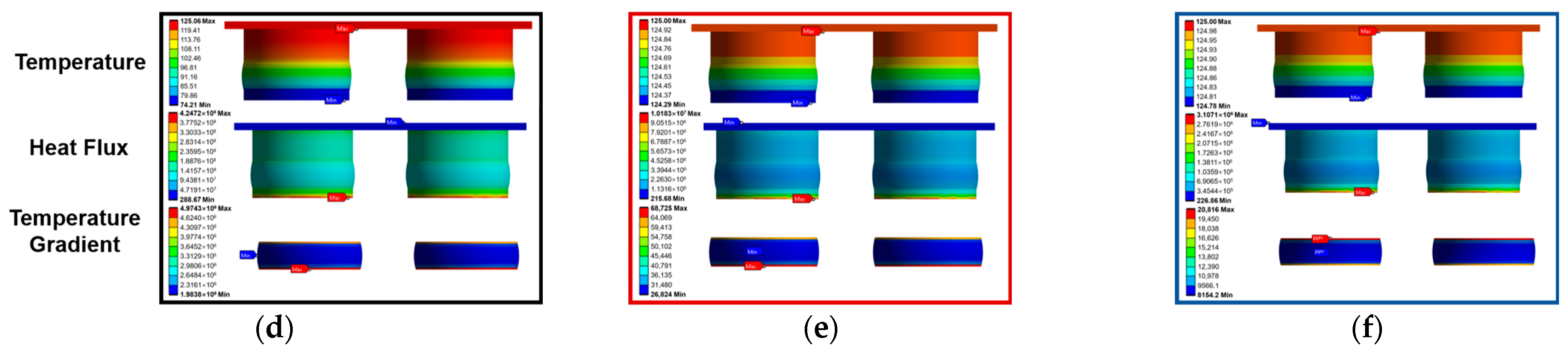

3.2. Multiphysics Field Distributions in Critical Microbump

3.3. Thermal Fatigue Life Prediction

3.4. Pitch Effect on Lifetime Prediction

3.5. Substrate Effect on Lifetime Prediction

4. Thermal Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moore, G.E. Cramming More Components onto Integrated Circuits, Reprinted from Electronics, Volume 38, Number 8, April 19, 1965, Pp.114 Ff. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Soc. Newsl. 2006, 11, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceruzzi, P.E. Moore’s Law and Technological Determinism: Reflections on the History of Technology. Technol. Cult. 2005, 46, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, F.; Lian, Z.; Jin, R.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, L. Research Progress of Hybrid Bonding Technology for Three-Dimensional Integration. Microelectron. Reliab. 2024, 155, 115372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, S. The Integrated Circuit Industry at a Crossroads: Threats and Opportunities. Chips 2022, 1, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Liu, C.; Zhou, P. Transistor Engineering Based on 2D Materials in the Post-Silicon Era. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2024, 1, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbalkar, P.; Bhaskar, P.; Kathaperumal, M.; Swaminathan, M.; Tummala, R.R. A Review of Polymer Dielectrics for Redistribution Layers in Interposers and Package Substrates. Polymers 2023, 15, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Su, C.; Li, C.; Chang, A.; An, B. Research Progress on Bonding Wire for Microelectronic Packaging. Micromachines 2023, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.H. Fan-Out Wafer-Level Packaging; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; ISBN 978-981-10-8883-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tummala, R.R.; Raj, P.M.; Aggarwal, A.; Mehrotra, G.; Koh, S.W.; Bansal, S.; Tiong, T.T.; Ong, C.K.; Chew, J.; Vaidyanathan, K.; et al. Copper Interconnections for High Performance and Fine Pitch Flipchip Digital Applications and Ultra-Miniaturized RF Module Applications. In Proceedings of the 56th Electronic Components and Technology Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 2 June 2006; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 102–111. [Google Scholar]

- Balucani, M.; Ciarniello, D.; Nenzi, P.; Bernardi, D.; Crescenzi, R.; Kholostov, K. New Selective Wet Processing. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 63rd Electronic Components and Technology Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 28–31 May 2013; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J.H.; Lee, N.-C. Solder Joints in PCB Assembly and Semiconductor Packaging. In Assembly and Reliability of Lead-Free Solder Joints; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiung, C.-K.; Chen, K.-N. A Review on Hybrid Bonding Interconnection and Its Characterization. IEEE Nanotechnol. Mag. 2024, 18, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, Y.; Fujii, N.; Aoyagi, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nishi, S.; Todaka, N.; Takeshita, S.; Taura, J.; Takahashi, H.; Nishimura, Y.; et al. Novel Stacked CMOS Image Sensor with Advanced Cu2Cu Hybrid Bonding. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–7 December 2016; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 8.4.1–8.4.4. [Google Scholar]

- Netzband, C.; Ryan, K.; Mimura, Y.; Ilseok, S.; Aizawa, H.; Ip, N.; Chen, X.; Fukushima, H.; Tan, S. 0.5 Μm Pitch Next Generation Hybrid Bonding with High Alignment Accuracy for 3D Integration. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 73rd Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Orlando, FL, USA, 30 May–2 June 2023; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1100–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Bekiaris, N.; Hsu, C.-H.; Xue, L.; Ramaswami, S.; Ding, T.; Probst, G.; Wernicke, T.; Uhrmann, T.; Wimplinger, M. 0.5 Μm Pitch Wafer-to-Wafer Hybrid Bonding at Low Temperatures with SiCN Bond Layer. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 74th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), Denver, CO, USA, 28–31 May 2014; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Ziegenhein, P.; Jiang, S.B. GPU-Based High-Performance Computing for Radiation Therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014, 59, R151–R182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Meng, G. Random Vibration Reliability of BGA Lead-Free Solder Joint. Microelectron. Reliab. 2014, 54, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yeow, O.G.; Poo, C.Y.; Jiang, T. Intermetallic Formation of Copper Pillar with Sn–Ag–Cu for Flip-Chip-On-Module Packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Technol. 2008, 31, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Nie, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, M.; Yan, C.; Yan, Q. Research on the Reliability of Micro LED High-Density Solder Joints under Thermal Cycling Conditions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2221, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Li, K.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Liu, G. Thermal Fatigue Reliability Improvement of Leadless Ceramic Chip Carrier Solder Joints. Microelectron. Reliab. 2022, 132, 114532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi Depiver, J.; Mallik, S.; Amalu, E.H. Comparing and Benchmarking Fatigue Behaviours of Various SAC Solders under Thermo-Mechanical Loading. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 8th Electronics System-Integration Technology Conference (ESTC), Tønsberg, Norway, 15 September 2020; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bertheau, J.; Hodaj, F.; Hotellier, N.; Charbonnier, J. Effect of Intermetallic Compound Thickness on Shear Strength of 25 Μm Diameter Cu-Pillars. Intermetallics 2014, 51, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, F.X.; Pang, J.H.L. Characterization of IMC Layer and Its Effect on Thermomechanical Fatigue Life of Sn–3.8Ag–0.7Cu Solder Joints. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 541, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, W.H.; Moon, M.-W.; Kim, C.-U.; Kang, S.H.; Jung, J.P.; Oh, K.H. Study of Fracture Mechanics in Testing Interfacial Fracture of Solder Joints. J. Electron. Mater. 2008, 37, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Chung, C.K.; Yang, C.R.; Kao, C.R. Single-Joint Shear Strength of Micro Cu Pillar Solder Bumps with Different Amounts of Intermetallics. Microelectron. Reliab. 2013, 53, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Fu, Y.; Kim, J.; Weng, L. Cu6Sn5 Morphology Transition and Its Effect on Mechanical Properties of Eutectic Sn-Ag Solder Joints. J. Electron. Mater. 2011, 40, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Hang, C.; Wang, C.; Yang, S.; Lin, P. Effects of Bump Size on Deformation and Fracture Behavior of Sn3.0Ag0.5Cu/Cu Solder Joints during Shear Testing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 529, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.P.; Xia, J.M.; Zhou, M.B.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.P. Solder Volume Effects on the Microstructure Evolution and Shear Fracture Behavior of Ball Grid Array Structure Sn-3.0Ag-0.5Cu Solder Interconnects. J. Electron. Mater. 2011, 40, 2425–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pang, J.H.L.; Che, F.X. Intermetallic Growth and Failure Study for Sn-Ag-Cu/ENIG PBGA Solder Joints Subject to Thermal Cycling. In Proceedings of the Electronic Components and Technology ECTC ’05, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 31 May–3 June 2005; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 682–686. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, L. Constitutive Equations for the Rate-Dependent Deformation of Metals at Elevated Temperatures. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1982, 104, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudi, R.; Geranmayeh, A.R.; Zahiri, B.; Marvasti, M.H. Effect of Rare Earth Element Additions on the Impression Creep of Sn–9Zn Solder Alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2010, 21, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, J.; Guo, Y.; He, C. Anand Model and FEM Analysis of SnAgCuZn Lead-Free Solder Joints in Wafer Level Chip Scale Packaging Devices. Microelectron. Reliab. 2014, 54, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.; Nie, X.; Bhate, D.; Subbarayan, G.; Chen, W.W.; Dutta, I. Constitutive Models for Intermediate- and High-Strain Rate Flow Behavior of Sn3.8Ag0.7Cu and Sn1.0Ag0.5Cu Solder Alloys. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 3, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depiver, J.A.; Mallik, S.; Amalu, E.H. Thermal Fatigue Life of Ball Grid Array (BGA) Solder Joints Made from Different Alloy Compositions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 125, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.-J.; Jang, D.-M.; Jang, J.-W.; Jang, J.-S.; Jeong, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J. Comparison of Thermal-Fatigue Lives of Conventional and Hybrid Solder Joints: Experiment and FE Analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedon-Gracia, A.; Woirgard, E.; Zardini, C.; Simon, G. An Assessment of the Connection between the Working, Operations of a Thyristor System Used in a Power Plant and Accelerated Ageing Tests. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, Ajaccio, France, 4–7 May 2004; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 803–807. [Google Scholar]

- Backes, B.; McDonough, C.; Smith, L.; Wang, W.; Geer, R.E. Effects of Copper Plasticity on the Induction of Stress in Silicon from Copper Through-Silicon Vias (TSVs) for 3D Integrated Circuits. J. Electron. Test. 2012, 28, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hsiao, H.-Y.; Chang, Y.-W.; Ouyang, F.; Tu, K.N. Thermomigration in Solder Joints. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2012, 73, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, F.; Liu, Y. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Micro Cu Doped Sn58Bi Solder Paste for Attaching LED Lamps. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tatsumi, H.; Nishikawa, H. A Comparative Numerical Study of Thermo-Mechanical Behavior among Various IMC Joints under Thermal Cycling Condition. J. Smart Process. 2024, 13, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.Z.; Schmid, M.; Zippelius, A.; Elger, G. LEDs Lifetime Prediction Modeling: Thermomechanical Simulation for SAC305 and SAC105. In Proceedings of the 2024 25th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE), Catania, Italy, 7–10 April 2024; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Z.; Morris, J.W. Characterization of Eutectic Sn-Bi Solder Joints. J. Electron. Mater. 1992, 21, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelkraut, S.; Frey, L.; Knoerr, M.; Schletz, A. Evolution of Shear Strength and Microstructure of Die Bonding Technologies for High Temperature Applications during Thermal Aging. In Proceedings of the 2010 12th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference, Singapore, 8–10 December 2010; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 660–667. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, D.; Huang, H.; McDonald, S.D.; Nogita, K. Creep and Mechanical Properties of Cu6Sn5 and (Cu,Ni)6Sn5 at Elevated Temperatures. J. Electron. Mater. 2013, 42, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.S.; Huang, H.Z.; Wu, B.Y. Simulation of Effect of Current Stressing on Reliability of Solder Joints with Cu-Pillar Bumps. Int. J. Mech. Aerosp. Ind. Mechatron. Manuf. Eng. 2010, 4, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.-C.; Yu, C.-F.; Chen, W.-H. Physical, Mechanical, Thermodynamic and Electronic Characterization of Cu11In9 Crystal Using First-Principles Density Functional Theory Calculation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 81, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Menezes, G.; McCann, S.; Jayaram, V.; Ray, U.; Sundaram, V.; Pulugurtha, R.; Smet, V.; Tummala, R. Board-Level Thermal Cycling and Drop-Test Reliability of Large, Ultrathin Glass BGA Packages for Smart Mobile Applications. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 7, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Lee, J.-H.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.-J.; Hong, Y. Substrate Thermal Conductivity Effect on Heat Dissipation and Lifetime Improvement of Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 253302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.-Y.; Kim, I.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, S.-B.; Jung, G.-J.; Park, B.-J.; Paik, K.-W. Studies on the Thermal Cycling Reliability of Fine Pitch Cu/SnAg Double-Bump Flip Chip Assemblies on Organic Substrates: Experimental Results and Numerical Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2008 58th Electronic Components and Technology Conference, Lake Buena Vista, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 27–30 May 2008; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 2035–2043. [Google Scholar]

- Beng, A.L.Y.; Hong, G.S.; Devarajan, M. Optimization of Thermal Vias for Thermal Resistance in FR-4 PCBs. In Proceedings of the Fifth Asia Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ASQED 2013), Penang, Malaysia, 26–28 August 2013; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Basiron, E.; Ismail, A.A.; Jalar, A.; Bakar, M.A.; Ahmad, A. Board Level-Component Solder Joints Normalized Crack Severity Index of Solid-State Drive with Different Reliability Temperature Cycle Test Profiles. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2025, 25, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, E.; Osterman, M.; Pecht, M. An Evaluation of Dwell Time and Mean Cyclic Temperature Parameters in the Engelmaier Model. Microelectron. Reliab. 2015, 55, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.H.L.; Low, T.H.; Xiong, B.S.; Che, F. Design for Reliability (DFR) Methodology for Electronic Packaging Assemblies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 5th Electronics Packaging Technology Conference (EPTC 2003), Singapore, 12 December 2003; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 470–478. [Google Scholar]

- Darveaux, R. Effect of Simulation Methodology on Solder Joint Crack Growth Correlation and Fatigue Life Prediction. J. Electron. Packag. 2002, 124, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darveaux, R.; Banerji, K. Constitutive Relations for Tin-Based-Solder Joints. In Proceedings of the 1992 Proceedings 42nd Electronic Components & Technology Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–20 May 1992; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 538–551. [Google Scholar]

- Toupin, R.A. Saint-Venant’s Principle. Arch. Ration Mech. Anal. 1965, 18, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.I.; Wu, S.C.; Liu, D.S.; Ni, C.Y.; Yuan, T.D. Global-to-Local Modeling and Experiment Investigation of HFCBGA Package Board-Level Solder Joint Reliability. J. Microelectron. Electron. Packag. 2007, 4, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.N. Recent Advances on Electromigration in Very-Large-Scale-Integration of Interconnects. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 5451–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Min, Z. Interfacial Reaction and IMC Growth between Bi-Containing Sn0.7Cu Solders and Cu Substrate during Soldering and Aging. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 582, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chen, Z. Interdependent Intermetallic Compound Growth in an Electroless Ni-P/Sn-3.5Ag Reaction Couple. J. Electron. Mater. 2011, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pang, J.H.L.; Prakash, K.H.; Low, T.H. Isothermal and Thermal Cycling Aging on IMC Growth Rate in Lead-Free and Lead-Based Solder Interface. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Technol. 2005, 28, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chung, H.Y.; Lai, Y.S.; Kao, C.R. Interaction Between Ni and Cu Across 95Pb-5Sn High-Lead Layer. J. Electron. Mater. 2010, 39, 2662–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, D.; Tian, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yan, C. Interfacial Behaviors of Sn-Pb, Sn-Ag-Cu Pb-Free and Mixed Sn-Ag-Cu/Sn-Pb Solder Joints during Electromigration. Microelectron. Reliab. 2017, 73, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, S.; Jung, D.-H.; Jung, J.P. Effect of High Temperature High Humidity and Thermal Shock Test on Interfacial Intermetallic Compounds (IMCs) Growth of Low Alpha Solders. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 8116–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-G.; Lee, C.-Y.; Jung, S.-B. Interfacial Reactions and Intermetallic Compound Growth between Indium and Copper. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2004, 15, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, R.; Li, F.; Ci, W.; Lin, Q. Wetting of Cu and Cu-Sn IMCs by Sn-Bi Alloys over Wide Composition at 350 °C. J. Electron. Mater. 2019, 48, 4660–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Vieregge, K.; Gust, W. Interface Diffusion in Eutectic Pb–Sn Solder. Acta Mater. 1998, 47, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pu, L.; Yang, Y.; He, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Tan, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Tu, K.N. A High-Entropy Alloy as Very Low Melting Point Solder for Advanced Electronic Packaging. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 7, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Watson, J.; Liu, S.; Madeni, J.C. Study of Intermetallic Compounds (IMC) That Form between Indium-Enriched SAC Solder Alloys and Copper Substrate. Weld. World 2017, 61, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güldali, D.; De Rose, A.; Oeser, S.; Kraft, A.; Tetzlaff, U. Intermetallic Phase Growth and Microhardness of Sn42Bi59 Solder Joints on Silicon Solar Cells. In Proceedings of the 40th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, Lisbon, Portugal, 18–22 September 2023; pp. 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, J. The Temperature Cycling Characteristic of Copper Pillar Solder Joints. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 14, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, J.-C. Thermo-Mechanical Reliability and Electrical Performance of Indium Interconnects and Under Bump Metallization. Master’ Thesis, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, C.; Sun, F.; Fang, H. Numerical Simulation of Reliability of 2.5D/3D Package Interconnect Structure under Temperature Cyclic Load. Microelectron. Reliab. 2021, 125, 114343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clech, J.-P.M.; Coyle, R.J.; Arfaei, B. Pb-Free Solder Joint Thermo-Mechanical Modeling: State of the Art and Challenges. JOM 2019, 71, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Shao, F.; Hua, T.; Liu, H.; Qiu, Y.; Li, J. Factors Influencing BGA Solder Joint Lifetime Prediction Based on the Darveaux Model. Microelectron. Comput. 2023, 40, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Low, T.H. Design-for-Reliability Methodology for Lead-Free Solder Joints. Master’s Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Yao, Q.; Lv, X.; Zhao, W. Submodelling Method for Modelling and Simulation of High-Density Electronic Assemblies. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1633, 012054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.W.; Patrick McCluskey, F. Reliability Assessment of Indium Solder for Low Temperature Electronic Packaging. Cryogenics 2009, 49, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, L.F. A Study of the Effects of Cyclic Thermal Stresses on a Ductile Metal. J. Fluids Eng. 1954, 76, 931–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gektin, V.; Bar-Cohen, A.; Ames, J. Coffin-Manson Fatigue Model of Underfilled Flip-Chips. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. Part A 1997, 20, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choa, S.-H.; Song, C.G.; Lee, H.S. Investigation of Durability of TSV Interconnect by Numerical Thermal Fatigue Analysis. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 12, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhu, W.; He, H. Comparison of Darveaux Model and Coffin-Manson Model for Fatigue Life Prediction of BGA Solder Joints. In Proceedings of the 2017 18th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT), Harbin, China, 16–19 August 2017; IEEE Access: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1474–1477. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.H.L.; Chong, D.Y.R. Flip Chip on Board Solder Joint Reliability Analysis Using 2-D and 3-D FEA Models. IEEE Trans. Adv. Packag. 2001, 24, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | Dimensions (μm) | Material | Density (Kg/m3) | Young’s Modulus (E/GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio (μ) | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion a/(10−6 °C−1) | Thermal Conductivity (W·m−1·°C−1) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chip | 2000 × 1750 × 75 | Si | 2300 | 110 | 0.24 | 2.6 | 147 | [34,38] |

| Trace/ Pillar/ Pad | H = 4 Φ = 55, H = 15 Φ = 55, H = 5.15 | Cu | 8889 | 129 | 0.34 | 17 | 400 | [34,39] |

| Diffusion Barrier | Φ = 55, H = 2 | Ni | 8902 | 210 | 0.312 | 13.1 | 91 | [40] |

| Solder 1 | Φ = 55, H = 15 | SAC105 | 7400 | 37 | 0.35 | 20 | 60 | [41] |

| Solder 2 | Sn63Pb37 | 8400 | 56 | 0.3 | 23.6 | 51 | [34] | |

| Solder3 | Sn42Bi58 | 8700 | 44 | 0.33 | 15 | 17 | [35,42] | |

| Solder 4 | Pb95Sn5 | 11,236 | 15.7 | 0.44 | 28.9 | 32 | [36,43] | |

| Solder 5 | Indium | 7290 | 11 | 0.45 | 32 | 81.6 | [19] | |

| IMC 1 | / | Cu6Sn5 | 8300 | 140 | 0.3 | 18.3 | 34.1 | [44,45] |

| IMC 2 | Cu3Sn | 8900 | 134 | 0.33 | 19 | 70.4 | [40] | |

| IMC 3 | Cu11In9 | 8450 | 90.4 | 0.311 | 24 | 30 | [46] | |

| Substrate 1 | 7000 × 7000 × 150 | Si | 2300 | 110 | 0.24 | 2.6 | 147 | [34,38] |

| Substrate 2 | Glass | 2480 | 74 | 0.23 | 9.8 | 1 | [47,48] | |

| Substrate 3 | Organic | 1910 | 22 | 0.28 | 18.5 | 0.3 | [49,50] |

| Solder Type | IMC Type | D (m2/s) | Q (KJ/mol) | T (Kelvin) | IMC Thickness (μm) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAC105 | Cu6Sn5 | 3.50 × 10−19 | 10.4 | 373.15 | 1.32 | [64] |

| Sn63Pb37 | Cu6Sn5 | 2.50 × 10−19 | 79.8 | 373.15 | 1.12 | [63] |

| Sn42Bi58 | Cu3Sn | 1.84 × 10−19 | 63.5 | 373.15 | 1 | [70] |

| Pb95Sn5 | Cu3Sn | 1.84 × 10−19 | 52 | 373.15 | 0.96 | [62] |

| Indium | Cu11In9 | 6.45 × 10−18 | 34.16 | 373.15 | 5.65 | [65] |

| Solder | K1 (Cycles/PsiK2) | K2 (−) | K3 (10−7 in/Cycles/PsiK4) | K4 (−) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAC Solder | 40,300 | −1.66 | 4.26 | 1.04 | [75] |

| Lead-based eutectic solder | 56,300 | −1.62 | 3.34 | 1.04 | [76] |

| High-lead Solder | 71,000 | −1.62 | 2.76 | 1.05 | [77] |

| / | K1 (cycles/PaK2) | K2 (−) | K3 (μm/cycles PsiK4) | K4 (−) | / |

| Indium Solder | 2.4 × 1011 | −1.37 | 0.17 × 10−5 | 0.875 | [78] |

| Interconnect Pitch | 85 μm Pitch | 40 μm Pitch | 10 μm Pitch | 5 μm Pitch | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engelmaier | Darveaux | Engelmaier | Darveaux | Engelmaier | Darveaux | Engelmaier | Darveaux | |

| SAC105 | 320 | 103 | 197 | 48 | 73 | 3 | 29 | 1 |

| Indium | 1783 | 217 | 1254 | 72 | 275 | 6 | 182 | 2 |

| Sn42Bi58 | 2014 | / | 1609 | / | 342 | / | 194 | / |

| Sn63Pb37 | 2859 | 368 | 1764 | 123 | 391 | 14 | 313 | 9 |

| Pb95Sn5 | 3267 | 452 | 2571 | 146 | 1342 | 52 | 858 | 20 |

| 85 μm pitch | 40 μm pitch | 10 μm pitch | 5 μm pitch | |||||

| Coffin–Manson | Coffin–Manson | Coffin–Manson | Coffin–Manson | |||||

| Cu-Cu TCB | 7797 | 5260 | 2513 | 2136 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, H.; Bansal, S. Reliability of Fine-Pitch Cu-Microbumps for 3D Heterogeneous Integration: Effect of Solder, Pitch Scaling and Substrate Materials. Electron. Mater. 2025, 6, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040018

Guo H, Bansal S. Reliability of Fine-Pitch Cu-Microbumps for 3D Heterogeneous Integration: Effect of Solder, Pitch Scaling and Substrate Materials. Electronic Materials. 2025; 6(4):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040018

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Haohan, and Shubhra Bansal. 2025. "Reliability of Fine-Pitch Cu-Microbumps for 3D Heterogeneous Integration: Effect of Solder, Pitch Scaling and Substrate Materials" Electronic Materials 6, no. 4: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040018

APA StyleGuo, H., & Bansal, S. (2025). Reliability of Fine-Pitch Cu-Microbumps for 3D Heterogeneous Integration: Effect of Solder, Pitch Scaling and Substrate Materials. Electronic Materials, 6(4), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronicmat6040018