A Comparative Study on Modeling Methods for Deformation Prediction of Concrete Dams

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Environmental Factors and Correlations

2.1. Environmental Factors

2.2. Correlations

3. Models and Methods

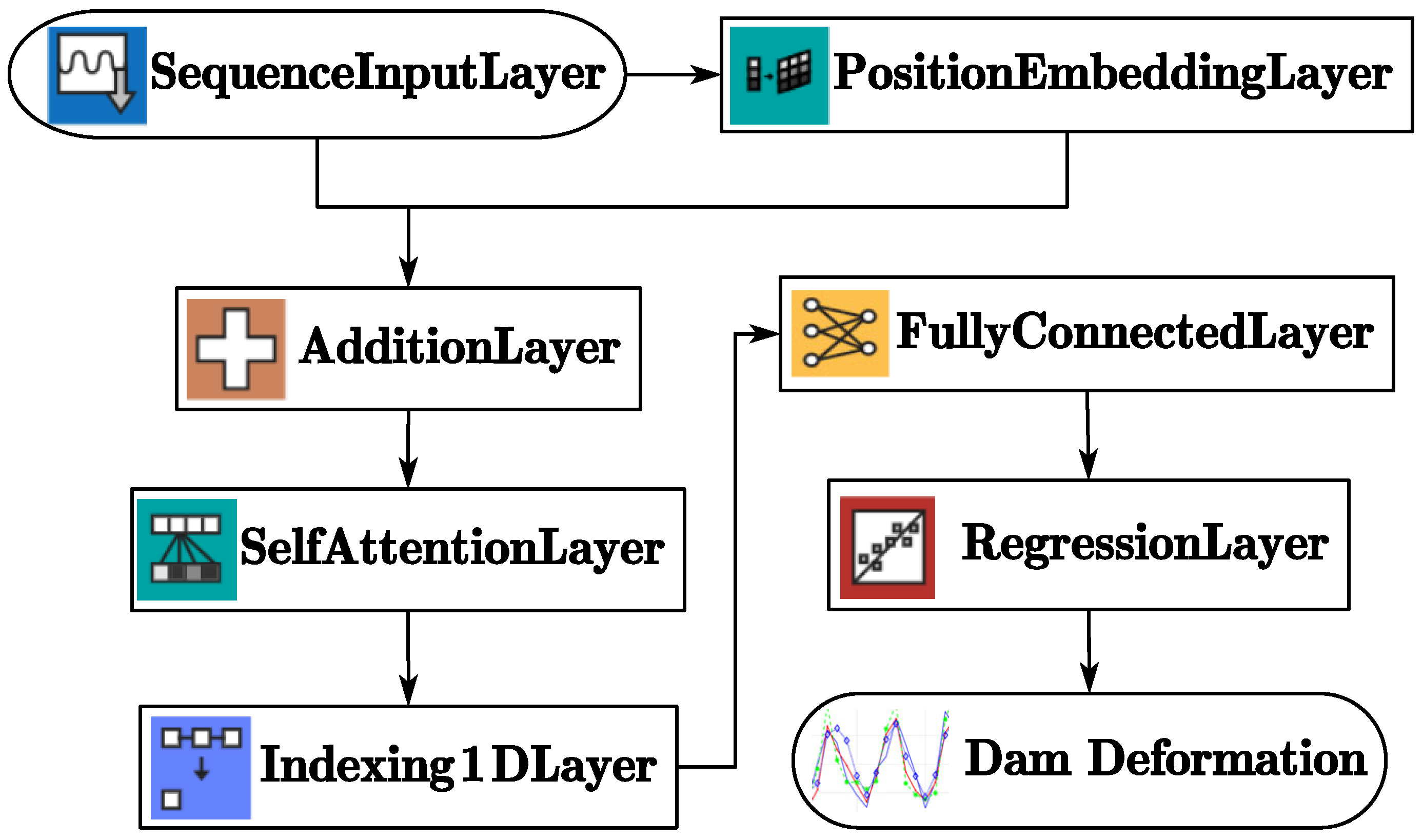

3.1. Transformer-Based Model

3.2. Multiple Linear Regression

3.3. Support Vector Regression

3.4. Random Forest

3.5. Gradient Boosting Decision Tree

3.6. Long Short-Term Memory Network

3.7. Weighted Average Model (WAM)

3.8. Prediction Accuracy Index

4. Experiments and Results

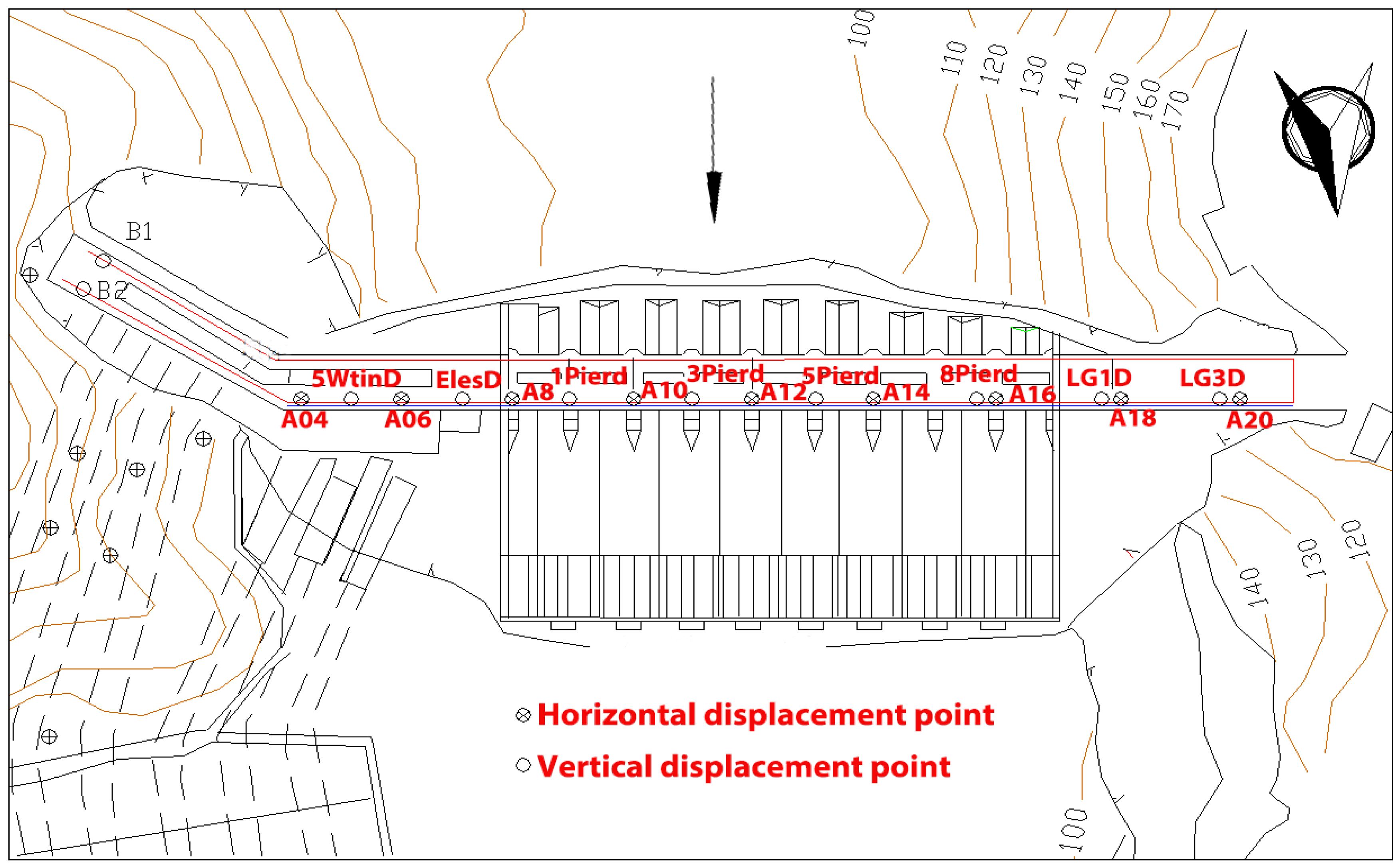

4.1. Zhexi Dam

4.2. Environmental Factors Data

4.3. Data Preprocessing

- (1)

- Forming the training datasets: The observational data covers a five-year period, with monthly observations collected over 60 cycles, offering a consistent and comprehensive view over time. The normalized datasets are alternately divided into two parts: training datasets and prediction datasets. Half of the total datasets were selected as training datasets, and the other half were selected as prediction datasets for accuracy validation. The datasets include input variables and output variables. The dam deformations are used as the output variables, and the corresponding environment factors are used as model input variables.

- (2)

- Training the learning machine: Initialize the parameters of the learning machine, perform the training iteration process, wait for the termination criterion to be met, and then obtain the regression model parameter.

- (3)

- Dam deformation prediction: The environment factor data are input into the trained machine learning regression model, the corresponding dam deformation is calculated, and the prediction accuracy and correlation coefficients are calculated.

4.4. Horizontal Displacement

4.5. Vertical Displacement

5. Discussion and Analysis

5.1. Interpretability of Models for Engineering Applications

5.2. Technical Discussion and Critical Interpretation of Results

5.3. Interpretation of Machine-Learned Relationships and Feature Importance

5.4. Engineering Interpretation

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The MIC, Pearson, Kendall, and Spearman correlation indices reveal that dam deformation is closely related to physical factors such as air temperature, reservoir water temperature, reservoir water level, and dam aging. It is possible to establish an accurate prediction model for dam deformation. It is revealed that Zhexi Dam is operating under safe conditions and that its periodic deformation corresponds to environmental factors within an allowable range. All the models’ prediction errors are less than 2.0 mm.

- (2)

- Different models exhibited varying performance in the same practical application. Among the seven models evaluated, the MLR model yielded a relatively high prediction RMSE. In scenarios with limited samples, the SVM model demonstrated superior prediction accuracy. Our results indicate that the weighted average ensemble model achieves higher prediction accuracy than any individual constituent model, albeit at the cost of requiring multiple models and substantial computational resources. The Transformer model, first introduced in 2017, was incorporated into the analysis. The prediction model based on a standalone Transformer architecture demonstrates considerable accuracy and distinct advantages, showing promise as a novel deformation prediction approach for concrete dams.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIC | maximum information coefficient |

| MLR | multiple linear regression |

| GBDT | gradient boosting decision tree |

| RF | random forest |

| SVM | support vector machine |

| LSTM | long short-term memory |

| WAM | weighted average model |

| RMSE | root mean squared error |

References

- Gu, H.; Yang, M.; Gu, C.S.; Huang, X.F. A factor mining model with optimized random forest for concrete dam deformation monitoring. Water Sci. Eng. 2021, 14, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, W.J. A Procedure for Estimating Loss of Life Caused by Dam Failure—DSO-99-06; Bureau of Reclamation: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, T.P. Lessons in social responsibility from the austin dam failure. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2006, 22, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Smith, J.A.; Tian, F. Typhoon Nina the August 1975 flood over central China. J. Hydrometeorol. 2017, 18, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Ontiveros, J.R.; Martinez-Felix, C.A.; Vazquez-Becerra, G.E.; Gaxiola-Camacho, J.R.; Melgarejo-Morales, A.; Padilla-Velazco, J. Monitoring of local deformations and reservoir water level for a gravity type dam based on GPS observations. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 69, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L.; Csépányi-Fürjes, L.; Tewabe, W. Transformer Models in Natural Language Processing. In The 17th International Conference Interdisciplinarity in Engineering; Inter-ENG 2023; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Moldovan, L., Gligor, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training; Computer Science, Linguistics; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bukenya, P.; Moyo, P.; Beushausen, H.; Oosthuizen, C. Health monitoring of concrete dams: A literature review. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2014, 4, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konakoglu, B.; Cakir, L.; Yilmaz, V. Monitoring the deformation of a concrete dam: A case study on the Deriner Dam, Artvin, Turkey. Geomat. Natl. Hazards Risk. 2020, 11, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, R.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Q. Simultaneous estimation of dam displacements and reservoir level variation from GPS measurements. Measurement 2018, 122, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Armenteros, A.M.; Lazecky, M.; Hlaváčová, I.; Bakoň, M.; Delgado, J.M.; Sousa, J.J.; Lamas-Fernández, F.; Marchamalo, M.; Caro-Cuenca, M.; Papco, J.; et al. Deformation monitoring of dam infrastructures via spaceborne MT-InSAR. The case of La Viñuela (Málaga, southern Spain). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 138, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sui, X.; Liu, Y.; Gu, H.; Xu, B.; Xia, Q. Prediction and interpretation of the deformation behaviour of high arch dams based on a measured temperature field. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 13, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Wu, Y.R.; Ma, J.T.; Li, J.J. Structural identification of super high arch dams using Gaussian process regression with improved salp swarm algorithm. Eng. Struct. 2023, 286, 116150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmokre, A.; Mihoubi, M.K.; Santillán, D. Analysis of dam behavior by statistical models: Application of the random forest approach. KSCE J. Civ Eng. 2019, 23, 4800–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J. Interpretation of concrete dam behaviour with artificial neural network and multiple linear regression models. Eng. Struct. 2011, 33, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranković, V.; Grujović, N.; Divac, D.; Milivojević, N. Development of support vector regression identification model for prediction of dam structural behaviour. Struct. Saf. 2014, 48, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, F.; Toledo, M.Á.; Oñate, E.; Suárez, B. Interpretation of dam deformation and leakage with boosted regression trees. Eng. Struct. 2016, 119, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Pan, J.W.; Ren, Y.S.; Wu, Z.G.; Wang, J.T. Coupling prediction model for long-term displacements of arch dams based on long short-term memory network. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2020, 27, e2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Kang, F.; Li, J.; Wang, F. Displacement prediction model for high arch dams using long short-term memory based encoder-decoder with dual-stage attention considering measured dam temperature. Eng. Struct. 2023, 280, 115686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, F.H. Comparison of hierarchical clustering-based deformation prediction models for high arch dams during the initial operation period. J. Civil Struct. Health Monit. 2021, 11, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshef, D.N.; Reshef, Y.A.; Finucane, H.K.; Grossman, S.R.; McVean, G.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Lander, E.S.; Mitzenmacher, M.; Sabeti, P.C. Detecting Novel Associations in Large Data Sets. Science 2011, 334, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Meng, D.Z.; Xu, D.X. Survey of the research process for statistical correlation analysis. Math. Model. Its Appl. 2014, 3, 1–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Xu, Y.L.; Gu, C.S.; Bao, T.F.; Xia, Q.; Hu, K. Hysteretic effect considered monitoring model for interpreting abnormal deformation behavior of arch dams: A case study. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2019, 26, e2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Bao, T.; Shu, X.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, K. A Hybrid Model Integrating Principal Component Analysis, Fuzzy C-Means, and Gaussian Process Regression for Dam Deformation Prediction. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 4293–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.S.; Tang, G.; Wang, Q.Y.; Luo, L.X.; Long, S.C. A Method for Forest Vegetation Height Modeling Based on Aerial Digital Orthophoto Map and Digital Surface Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4404307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.N.; Wu, J.B.; Zhu, J.P.; Xie, B.C. A review of technologies on random forests. Stat. Inf. Forum. 2011, 26, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H. Machine Learning; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.S.; Huang, Z.X. A brief theoretical overview of random forests. J. Integr. Technol. 2013, 2, 1–7. Available online: https://jcjs.siat.ac.cn/en/article/id/201301001 (accessed on 15 August 2025). (In Chinese).

- Wu, W.M.; Wang, J.X.; Huang, Y.S.; Zhao, H.Y.; Wang, X.T. A novel way to determine transient heat flux based on GBDT machine learning algorithm. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 179, 121746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Bengio, Y.; Frasconi, P.; Schmidhuber, J. Gradient flow in recurrent nets: The difficulty of learning long-term dependencies. In A Field Guide to Dynamical Recurrent Neural Networks; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Schmidhuber, J. Framewise, phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 2005, 18, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, D. A predictive maintenance model using long short-term memory neural networks and Bayesian inference. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environment Factors | Horizontal Displacement | Vertical Displacement | Crack Width | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | Pearson | Kendall | Spearman | MIC | Pearson | Kendall | Spearman | MIC | Pearson | Kendall | Spearman | |

| T1–10 | 0.9000 | −0.8698 | −0.7127 | −0.8874 | 0.8816 | −0.9395 | −0.7920 | −0.9371 | 0.8167 | 0.0067 | −0.0002 | 0.0100 |

| T11–20 | 0.7402 | −0.7888 | −0.5972 | −0.8113 | 0.9541 | −0.9523 | −0.8305 | −0.9581 | 0.7837 | −0.0579 | −0.0376 | −0.0419 |

| T21–35 | 0.7324 | −0.7312 | −0.5384 | −0.7521 | 0.9541 | −0.9561 | −0.8271 | −0.9592 | 0.8196 | −0.1396 | −0.0917 | −0.1093 |

| T36–50 | 0.5327 | −0.5876 | −0.4111 | −0.6089 | 1.0000 | −0.8940 | −0.6988 | −0.8940 | 0.8186 | −0.2209 | −0.1369 | −0.1718 |

| T51–70 | 0.3369 | −0.3640 | −0.2469 | −0.3949 | 0.6944 | −0.7763 | −0.5677 | −0.7813 | 0.7567 | −0.2862 | −0.1758 | −0.2258 |

| T71–90 | 0.2741 | −0.0977 | −0.0714 | −0.1189 | 0.5124 | −0.5537 | −0.3739 | −0.5562 | 0.7140 | −0.3355 | −0.2033 | −0.2663 |

| Twater | 0.4868 | −0.6453 | −0.4636 | −0.6698 | 0.8851 | −0.9186 | −0.7761 | −0.9344 | 0.8094 | −0.3442 | −0.2096 | −0.3002 |

| H1 | 0.2414 | 0.1066 | 0.0572 | 0.0961 | 0.3001 | −0.3253 | −0.1919 | −0.2877 | 0.7407 | −0.3552 | −0.2056 | −0.2990 |

| H2 | 0.2414 | 0.1080 | 0.0572 | 0.0961 | 0.3001 | −0.3206 | −0.1919 | −0.2877 | 0.7407 | −0.3527 | −0.2056 | −0.2990 |

| H3 | 0.2414 | 0.1091 | 0.0572 | 0.0961 | 0.3001 | −0.3154 | −0.1919 | −0.2877 | 0.7407 | −0.3499 | −0.2056 | −0.2990 |

| H4 | 0.2414 | 0.1100 | 0.0572 | 0.0961 | 0.3001 | −0.3099 | −0.1919 | −0.2877 | 0.7407 | −0.3467 | −0.2056 | −0.2990 |

| θ1 | 0.3638 | −0.1265 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.1109 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.9907 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| θ2 | 0.3638 | −0.1681 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.2209 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.7351 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| θ3 | 0.3638 | −0.1591 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.1716 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.9854 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| θ4 | 0.3638 | −0.1004 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.0833 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.9856 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| θ5 | 0.3638 | −0.0734 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.0813 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.9698 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| θ6 | 0.3638 | −0.1195 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.1012 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.9896 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| θ7 | 0.3638 | 0.1933 | 0.0708 | 0.0960 | 0.3679 | 0.1960 | 0.0515 | 0.0793 | 0.9999 | 0.9886 | 0.9499 | 0.9936 |

| θ8 | 0.3638 | −0.1339 | −0.0708 | −0.0960 | 0.3679 | −0.1890 | −0.0515 | −0.0793 | 0.9999 | −0.7352 | −0.9499 | −0.9936 |

| Point Name | MLR | RF | GBDT | SVM | LSTM | WAM | Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A04 | 1.364 | 1.060 | 1.200 | 0.969 | 0.994 | 0.960 | 0.845 |

| A05 | 1.320 | 1.052 | 1.249 | 1.183 | 1.071 | 0.976 | 1.039 |

| A06 | 1.518 | 0.824 | 0.770 | 0.815 | 0.961 | 0.695 | 0.871 |

| A07 | 1.148 | 1.184 | 1.135 | 1.115 | 1.765 | 1.034 | 1.252 |

| A08 | 1.228 | 1.180 | 1.221 | 1.097 | 1.486 | 1.053 | 1.213 |

| A09 | 0.981 | 1.110 | 1.106 | 0.864 | 1.434 | 0.855 | 1.134 |

| A10 | 2.156 | 1.968 | 1.762 | 1.721 | 2.128 | 1.537 | 1.536 |

| A11 | 1.999 | 1.738 | 1.664 | 1.392 | 1.698 | 1.293 | 1.205 |

| A12 | 1.628 | 1.551 | 1.571 | 1.149 | 2.175 | 1.085 | 1.089 |

| A13 | 1.317 | 1.532 | 1.890 | 1.065 | 1.913 | 0.997 | 1.095 |

| A14 | 1.351 | 1.127 | 1.351 | 0.942 | 1.654 | 0.848 | 1.134 |

| A15 | 0.936 | 1.159 | 1.594 | 0.907 | 1.310 | 0.873 | 1.001 |

| A16 | 1.486 | 1.111 | 1.171 | 0.910 | 1.091 | 0.899 | 0.788 |

| A17 | 1.440 | 1.370 | 1.286 | 1.169 | 2.121 | 1.183 | 1.000 |

| A18 | 1.075 | 1.191 | 1.269 | 1.052 | 1.291 | 0.992 | 0.991 |

| A19 | 1.102 | 0.724 | 0.855 | 0.775 | 0.770 | 0.614 | 0.960 |

| A20 | 1.534 | 0.609 | 0.647 | 0.672 | 0.754 | 0.568 | 0.801 |

| Point Name | MLR | RF | GBDT | SVM | LSTM | WAM | Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A04 | 0.574 | 0.574 | 0.467 | 0.654 | 0.612 | 0.663 | 0.765 |

| A05 | 0.650 | 0.693 | 0.520 | 0.598 | 0.626 | 0.730 | 0.604 |

| A06 | 0.547 | 0.796 | 0.760 | 0.728 | 0.566 | 0.839 | 0.767 |

| A07 | 0.835 | 0.825 | 0.835 | 0.838 | 0.512 | 0.867 | 0.829 |

| A08 | 0.786 | 0.775 | 0.772 | 0.808 | 0.598 | 0.826 | 0.771 |

| A09 | 0.893 | 0.859 | 0.865 | 0.912 | 0.713 | 0.918 | 0.845 |

| A10 | 0.830 | 0.804 | 0.852 | 0.857 | 0.762 | 0.890 | 0.887 |

| A11 | 0.827 | 0.807 | 0.828 | 0.878 | 0.812 | 0.897 | 0.911 |

| A12 | 0.885 | 0.825 | 0.844 | 0.908 | 0.578 | 0.916 | 0.924 |

| A13 | 0.916 | 0.834 | 0.803 | 0.919 | 0.703 | 0.931 | 0.917 |

| A14 | 0.896 | 0.913 | 0.855 | 0.934 | 0.753 | 0.949 | 0.899 |

| A15 | 0.913 | 0.858 | 0.772 | 0.911 | 0.791 | 0.918 | 0.890 |

| A16 | 0.852 | 0.835 | 0.820 | 0.902 | 0.834 | 0.905 | 0.923 |

| A17 | 0.790 | 0.791 | 0.824 | 0.853 | 0.281 | 0.858 | 0.881 |

| A18 | 0.866 | 0.772 | 0.758 | 0.822 | 0.706 | 0.847 | 0.859 |

| A19 | 0.714 | 0.697 | 0.670 | 0.764 | 0.578 | 0.800 | 0.397 |

| A20 | 0.253 | 0.682 | 0.663 | 0.563 | 0.359 | 0.722 | 0.230 |

| Point Name | MLR | RF | GBDT | SVM | LSTM | WAM | Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG3D | 0.762 | 0.642 | 0.676 | 0.559 | 0.681 | 0.528 | 0.642 |

| LG2D | 0.969 | 0.767 | 1.023 | 0.623 | 0.749 | 0.553 | 0.519 |

| LG1D | 0.748 | 0.707 | 0.791 | 0.667 | 0.707 | 0.609 | 0.608 |

| LgwD | 1.018 | 0.803 | 0.944 | 0.691 | 0.808 | 0.639 | 0.593 |

| 8PierD | 0.960 | 0.827 | 0.846 | 0.795 | 0.902 | 0.665 | 0.645 |

| 7PierD | 0.974 | 0.900 | 0.948 | 0.801 | 0.968 | 0.711 | 0.727 |

| 6PierD | 0.934 | 0.878 | 0.878 | 0.801 | 0.996 | 0.724 | 0.656 |

| 5PierD | 1.066 | 0.942 | 0.922 | 0.830 | 1.000 | 0.732 | 0.731 |

| 4PierD | 1.018 | 0.919 | 0.987 | 0.799 | 1.027 | 0.749 | 0.664 |

| 3PierD | 0.999 | 0.882 | 0.910 | 0.795 | 0.955 | 0.732 | 0.691 |

| 2PierD | 0.975 | 0.955 | 0.978 | 0.831 | 0.996 | 0.770 | 0.675 |

| 1PierD | 1.006 | 0.886 | 0.879 | 0.807 | 0.970 | 0.717 | 0.652 |

| RgwD | 0.744 | 0.874 | 0.974 | 0.701 | 0.811 | 0.637 | 0.695 |

| ElesD | 0.738 | 0.918 | 0.915 | 0.727 | 0.773 | 0.669 | 0.695 |

| 6WtinD | 0.859 | 0.943 | 0.936 | 0.815 | 0.887 | 0.755 | 0.807 |

| 5WtinD | 0.828 | 0.996 | 1.020 | 0.870 | 0.861 | 0.758 | 0.717 |

| 4WtinD | 0.827 | 0.938 | 0.898 | 0.799 | 0.836 | 0.705 | 0.638 |

| Point Name | MLR | RF | GBDT | SVM | LSTM | WAM | Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG3D | 0.877 | 0.933 | 0.915 | 0.946 | 0.904 | 0.959 | 0.929 |

| LG2D | 0.850 | 0.925 | 0.833 | 0.945 | 0.910 | 0.966 | 0.968 |

| LG1D | 0.894 | 0.925 | 0.893 | 0.925 | 0.909 | 0.946 | 0.930 |

| LgwD | 0.913 | 0.960 | 0.927 | 0.964 | 0.945 | 0.974 | 0.975 |

| 8PierD | 0.950 | 0.975 | 0.968 | 0.975 | 0.957 | 0.983 | 0.980 |

| 7PierD | 0.949 | 0.972 | 0.958 | 0.973 | 0.950 | 0.981 | 0.975 |

| 6PierD | 0.954 | 0.973 | 0.967 | 0.974 | 0.949 | 0.979 | 0.980 |

| 5PierD | 0.940 | 0.968 | 0.964 | 0.972 | 0.948 | 0.979 | 0.975 |

| 4PierD | 0.947 | 0.968 | 0.962 | 0.975 | 0.946 | 0.978 | 0.979 |

| 3PierD | 0.947 | 0.971 | 0.962 | 0.974 | 0.952 | 0.978 | 0.977 |

| 2PierD | 0.953 | 0.967 | 0.960 | 0.971 | 0.951 | 0.976 | 0.977 |

| 1PierD | 0.947 | 0.969 | 0.966 | 0.968 | 0.950 | 0.977 | 0.984 |

| RgwD | 0.959 | 0.949 | 0.930 | 0.966 | 0.951 | 0.972 | 0.964 |

| ElesD | 0.941 | 0.916 | 0.920 | 0.945 | 0.936 | 0.955 | 0.945 |

| 6WtinD | 0.939 | 0.928 | 0.927 | 0.946 | 0.935 | 0.954 | 0.950 |

| 5WtinD | 0.937 | 0.913 | 0.905 | 0.932 | 0.933 | 0.950 | 0.951 |

| 4WtinD | 0.935 | 0.916 | 0.922 | 0.939 | 0.933 | 0.953 | 0.960 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, X.; Zhu, X.; Tang, Z. A Comparative Study on Modeling Methods for Deformation Prediction of Concrete Dams. Modelling 2025, 6, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040154

Deng X, Zhu X, Tang Z. A Comparative Study on Modeling Methods for Deformation Prediction of Concrete Dams. Modelling. 2025; 6(4):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040154

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Xingsheng, Xu Zhu, and Zhongan Tang. 2025. "A Comparative Study on Modeling Methods for Deformation Prediction of Concrete Dams" Modelling 6, no. 4: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040154

APA StyleDeng, X., Zhu, X., & Tang, Z. (2025). A Comparative Study on Modeling Methods for Deformation Prediction of Concrete Dams. Modelling, 6(4), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/modelling6040154