Incidentally Identified Basal Plate Myometrial Fibers and Hemorrhage Risk in the Subsequent Pregnancy

Abstract

1. Introduction

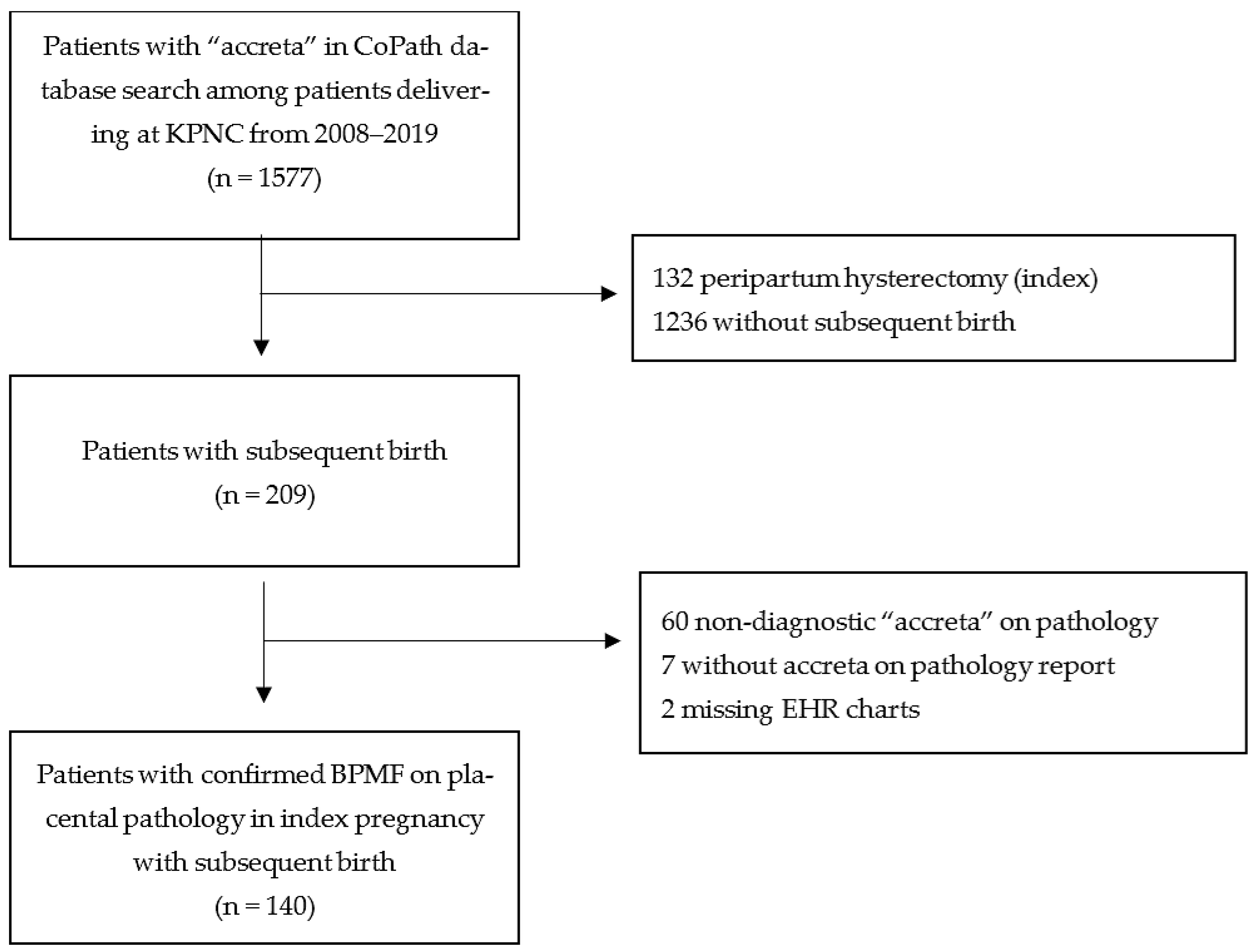

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EHR | electronic health record |

| KPNC | Kaiser Permanente Northern California |

| BPMF | basal plate myometrial fiber |

| PAS | placenta accreta spectrum |

References

- Belfort, M. Placenta Accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gelany, S.; Mosbeh, M.H.; Ibrahim, E.M.; Mohammed, M.; Khalifa, E.M.; Abdelhakium, A.K.; Yousef, A.M.; Hassan, H.; Goma, K.; Alghany, A.A.; et al. Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS) disorders: Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of different management strategies in a tertiary referral hospital in Minia, Egypt: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux, E.; Bunce, C.; Grønbeck, L.; Langhoff-Roos, J. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, R.M.; Landon, M.B.; Rouse, D.J.; Leveno, K.J.; Spong, C.Y.; Thom, E.A.; Moawad, A.H.; Caritis, S.N.; Harper, M.; Wapner, R.J.; et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 1226–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.C.; Lee, R.H.; Chmait, R.H. Emergency postpartum hysterectomy for uncontrolled postpartum bleeding: A systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshkoli, T.; Weintraub, A.Y.; Sergienko, R.; Sheiner, E. Placenta accreta: Risk factors, perinatal outcomes, and consequences for subsequent births. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 208, 219.e1–219.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinograd, A.; Wainstock, T.; Mazor, M.; Mastrolia, S.A.; Beer-Weisel, R.; Klaitman, V.; Dukler, D.; Hamou, B.; Benshalom-Tirosh, N.; Vinograd, O.; et al. A prior placenta accreta is an independent risk factor for post-partum hemorrhage in subsequent gestations. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 187, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.L.; Baergen, R.; Ernst, L.M.; Katzman, P.J.; Jacques, S.M.; Jauniaux, E.; Khong, T.Y.; Metlay, L.A.; Poder, L.; Qureshi, F.; et al. Classification and reporting guidelines for the pathology diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders: Recommendations from an expert panel. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 2382–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larish, A.; Horst, K.; Brunton, J.; Schenone, M.; Branda, M.; Mehta, R.; Packard, A.; VanBuren, W.; Norgan, A.; Shahi, M.; et al. Focal-occult placenta accreta: A clandestine source of maternal morbidity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, C.; Battarbee, A.N.; Ernst, L.M.; Peaceman, A.M. Occult Placenta Accreta: Risk Factors, Adverse Obstetrical Outcomes, and Recurrence in Subsequent Pregnancies. Am. J. Perinatol. 2019, 36, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.S.; Linn, R.L.; Ernst, L.M. Does the presence of placental basal plate myometrial fibres increase the risk of subsequent morbidly adherent placenta: A case-control study. BJOG 2016, 123, 2140–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, R.L.; Miller, E.S.; Lim, G.; Ernst, L.M. Adherent basal plate myometrial fibers in the delivered placenta as a risk factor for development of subsequent placenta accreta. Placenta 2015, 36, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeca, C.; Little, S.E.; Carusi, D.A. Pathologically Diagnosed Placenta Accreta and Hemorrhagic Morbidity in a Subsequent Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, H.; Hessami, K.; Salmanian, B.; Castro, E.C.; Kopkin, R.; Hecht, J.L.; Gogia, S.; Jackson, J.N.; Dong, E.; Fox, K.A.; et al. Basal Plate Myofibers and the Risk of Placenta Accreta Spectrum in the Subsequent Pregnancy: A Large Single-Center Cohort. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 41, e2286–e2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, D.S.; Wyand, R.; Cramer, S. Recurrence of Basal Plate Myofibers, with Further Consideration of Pathogenesis. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2019, 38, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, A.; Hedderson, M.M.; Ching, J.; Kim, C.; Peng, T.; Crites, Y.M. Referral to telephonic nurse management improves outcomes in women with gestational diabetes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 491.e1–491.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, S.M.; Qureshi, F.; Trent, V.S.; Ramirez, N.C. Placenta accreta: Mild cases diagnosed by placental examination. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1996, 15, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanek, J.; Drummond, Z. Occult placenta accreta: The missing link in the diagnosis of abnormal placentation. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2007, 10, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, H.J.; Nippita, T.A.; Torvaldsen, S.; Ibiebele, I.; Ford, J.B.; Patterson, J.A. Outcomes of Subsequent Births After Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, K.M.; Anwar, A.; Lindow, S.W. The recurrence risk of placenta accreta following uterine conserving management. J. Neonatal Perinat. Med. 2015, 8, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberg, A.S.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Palmsten, K.; Almqvist, C.; Bateman, B.T. Patterns of recurrence of postpartum hemorrhage in a large population-based cohort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 210, 229.e1–229.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiter, L.; Kazemier, B.M.; Mol, B.W.J.; Pajkrt, E. Incidence and recurrence rate of postpartum hemorrhage and manual removal of the placenta: A longitudinal linked national cohort study in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 238, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbetta-Rastelli, C.M.; Friedman, A.M.; Sobhani, N.C.; Arditi, B.; Goffman, D.; Wen, T. Postpartum Hemorrhage Trends and Outcomes in the United States, 2000–2019. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 7: Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, e259–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Selected Characteristics | Total (N = 140) n (%) or Mean (SD) | sBPMF (N = 90, 64%) n (%) or Mean (SD) | aBPMF (N = 50, 36%) n (%) or Mean (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (Year) at the first prenatal visit | |||||

| Mean (Year) | 30.8 (4.9) | 31.5 (4.6) | 29.5 (5.3) | 0.023 | |

| <35 years old | 115 (82.1) | 72 (80.0) | 43 (86.0) | 0.374 | |

| ≥35 years old | 25 (17.9) | 18 (20.0) | 7 (14.0) | ||

| Parity | 0.452 | ||||

| 0–1 births >20 weeks | 122 (87.1) | 77 (85.6) | 45 (90.0) | ||

| >1 birth >20 weeks | 18 (12.9) | 13 (14.4) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.031 | ||||

| White | 76 (54.3) | 53 (58.9) | 23 (46.0) | ||

| Black | 13 (9.3) | 4 (4.4) | 9 (18.0) | ||

| Hispanic non-Black | 22 (15.7) | 12 (13.3) | 10 (20.0) | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 25 (17.9) | 17 (18.9) | 8 (16.0) | ||

| Native American/Multiracial/Other/Unknown | 4 (2.9) | 4 (4.4) | 0 | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | 0.939 | ||||

| <30 | 106 (75.7) | 67 (74.4) | 39 (78.0) | ||

| 30–34 | 23 (16.4) | 16 (17.8) | 7 (14.0) | ||

| 35–39 | 6 (4.3) | 4 (4.4) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| ≥40 | 5 (3.6) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| Prior uterine surgery | 15 (10.7) | 9 (10.0) | 6 (12.0) | 0.714 | |

| Placenta previa at time of delivery | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | |

| Cesarean at time of delivery | 50 (35.7) | 18 (20.0) | 32 (64) | <0.001 | |

| In vitro fertilization (IVF) | 0.901 | ||||

| Yes | 6 (4.3) | 4 (4.4) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| No | 134 (95.7) | 86 (95.6) | 48 (96.0) | ||

| Indication for pathologic examination | <0.001 | ||||

| Suspected accreta * | 89 (63.6) | 84 (93.3) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| Placental abruption | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.0) | ||

| Infection | 7 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (14.0) | ||

| Preterm labor | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| PPROM | 6 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (10.0) | ||

| IUGR | 10 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (20.0) | ||

| HTN | 7 (5.0) | 3 (3.3) | 4 (8.0) | ||

| GDM | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| Outcome in Subsequent Pregnancy (N (%)) | Total (N = 140) | sBPMF * (N = 90) | aBPMF (N = 50) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhagic morbidity and/or adherent placenta | 39 (27.9) | 35 (38.9) | 4 (8.0) | <0.0001 |

| Adherent placenta only | 13 | 11 | 2 | |

| Hemorrhagic morbidity only † | 12 | 10 | 2 | |

| Both | 14 | 14 | 0 | |

| None | 101 (72.1) | 55 (61.1) | 46 (92.0) |

| Any Placental or Hemorrhagic Morbidity Outcome in Subsequent Pregnancy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of Accreta Symptoms in Index Pregnancy | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) * | p-Value |

| sBPMF † | 7.32 (2.42–22.12) | <0.001 | 10.2 (2.7–38.4) | <0.001 |

| aBPMF (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Model c-statistics | 0.676 | 0.735 | ||

| Total Subsequent Pregnancies (N = 140) | Hemorrhagic Morbidity * and/or Adherent Placenta (N = 39) | None (N = 101) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indication for placenta pathology in subsequent pregnancy, n (%) | ||||

| No placental pathology | 69 | 6 (8.7) | 63 (91.3) | <0.0001 |

| Yes placental pathology | 71 | |||

| Recurrent BPMF | 23 | 14 (60.9) | 9 (39.1) | |

| No Recurrent BPMF | 48 | 19 (39.6) | 29 (60.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, G.T.; Schauer, G.; Hung, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.; Ritterman Weintraub, M.; Greenberg, M.B. Incidentally Identified Basal Plate Myometrial Fibers and Hemorrhage Risk in the Subsequent Pregnancy. Reprod. Med. 2025, 6, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020010

Le GT, Schauer G, Hung Y-Y, Li Y, Ritterman Weintraub M, Greenberg MB. Incidentally Identified Basal Plate Myometrial Fibers and Hemorrhage Risk in the Subsequent Pregnancy. Reproductive Medicine. 2025; 6(2):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Gianna T., Galen Schauer, Yun-Yi Hung, Yunjie Li, Miranda Ritterman Weintraub, and Mara B. Greenberg. 2025. "Incidentally Identified Basal Plate Myometrial Fibers and Hemorrhage Risk in the Subsequent Pregnancy" Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 2: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020010

APA StyleLe, G. T., Schauer, G., Hung, Y.-Y., Li, Y., Ritterman Weintraub, M., & Greenberg, M. B. (2025). Incidentally Identified Basal Plate Myometrial Fibers and Hemorrhage Risk in the Subsequent Pregnancy. Reproductive Medicine, 6(2), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020010