Small Bowel Obstructions Caused by Barbed Sutures in Robotic Surgery: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

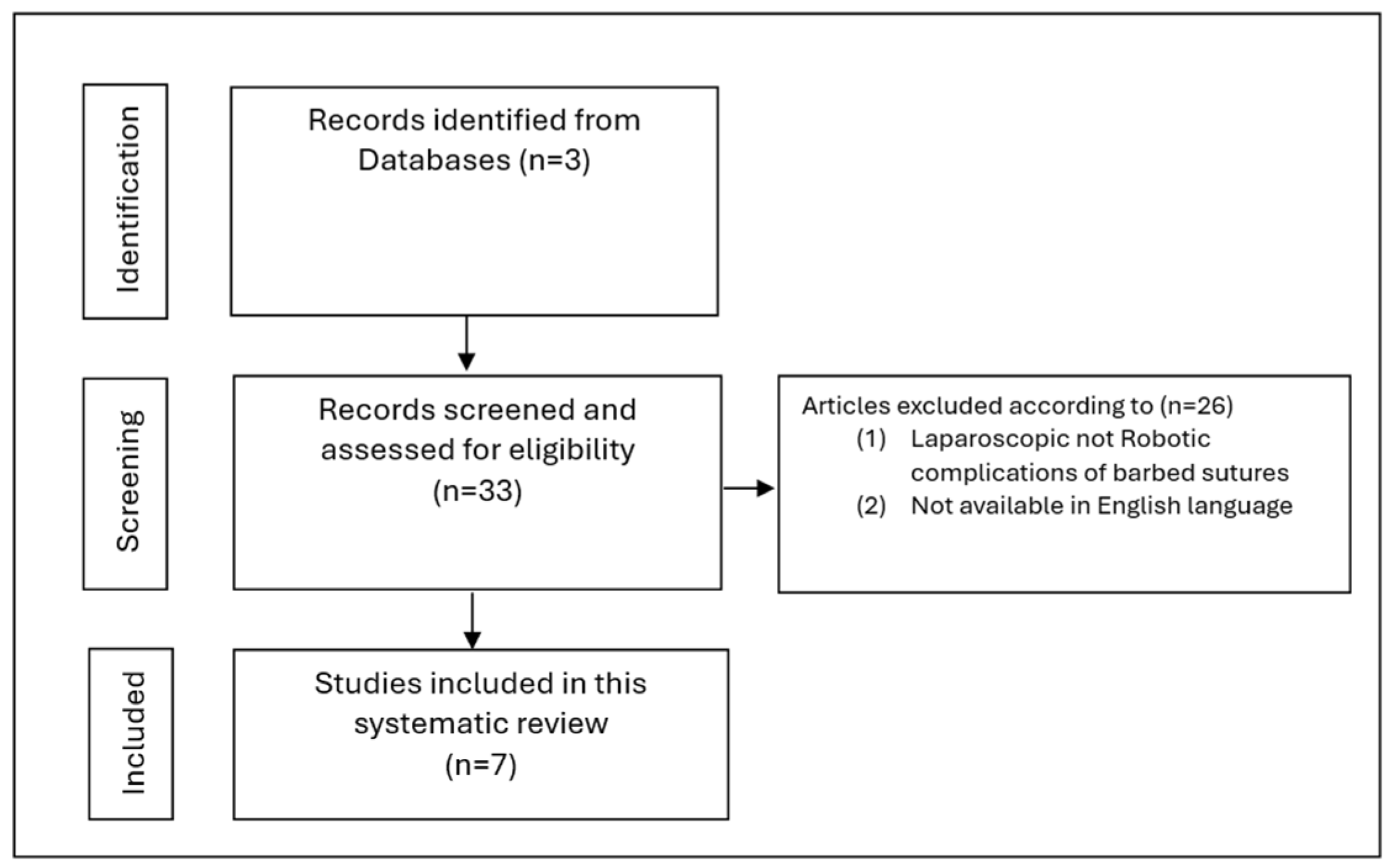

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Types of Index Operations

3.2. Time to Presentation and Common Clinical Presentation

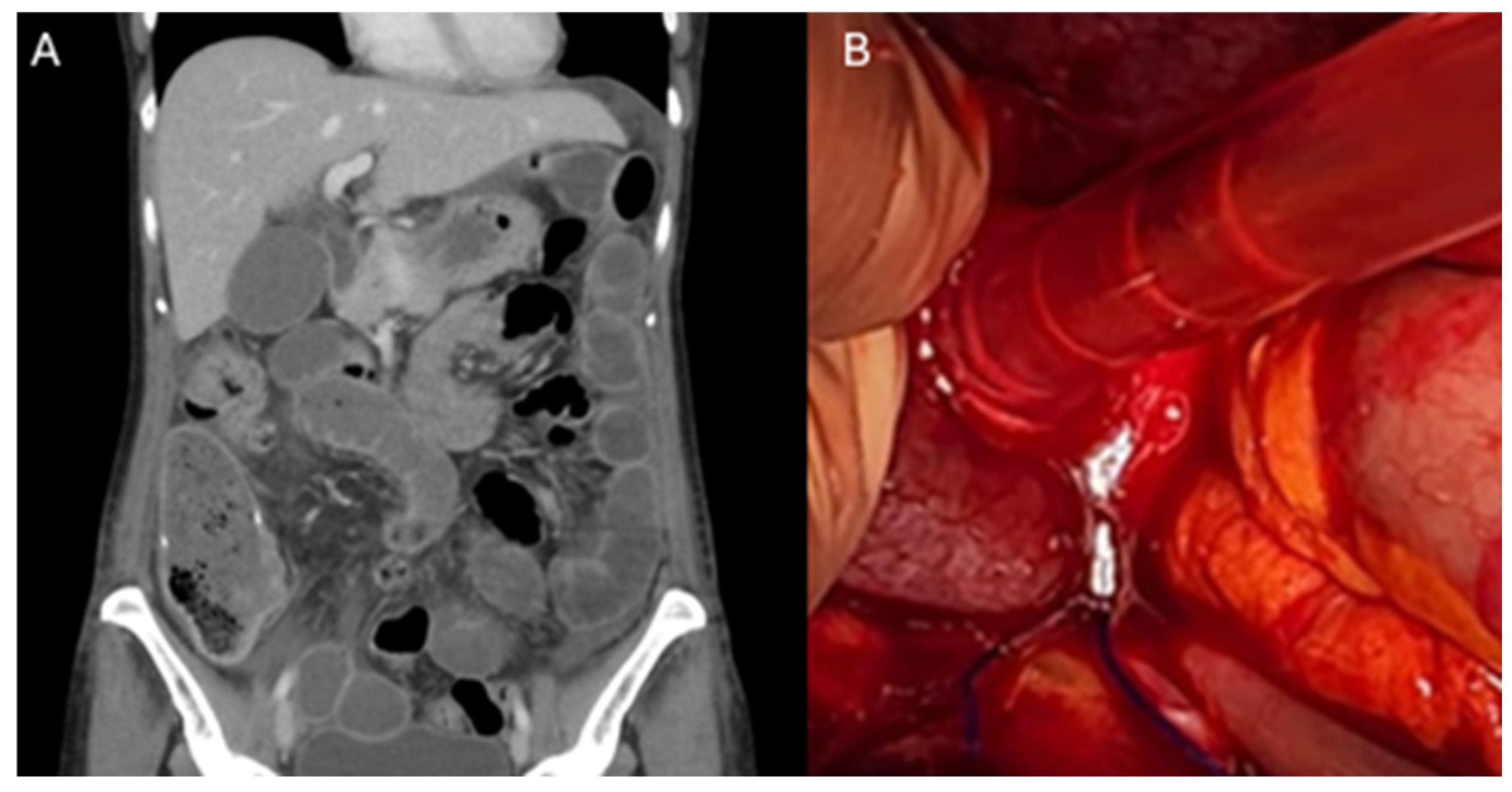

3.3. Intraoperative Findings and Treatments

4. Discussion

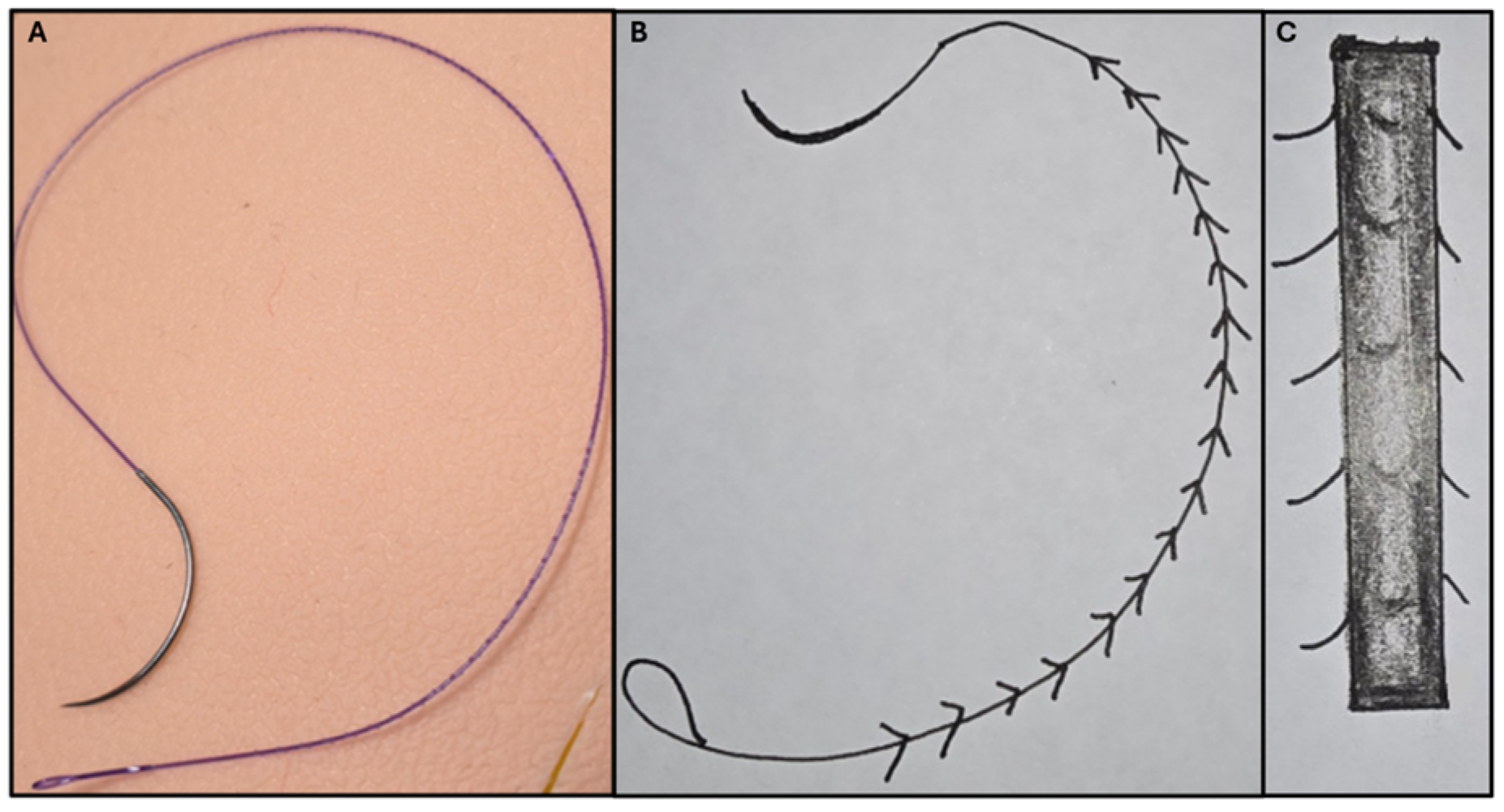

4.1. The Use of Barbed Sutures in Robotic Surgery

4.2. Small Bowel Obstructions Caused by Barbed Sutures

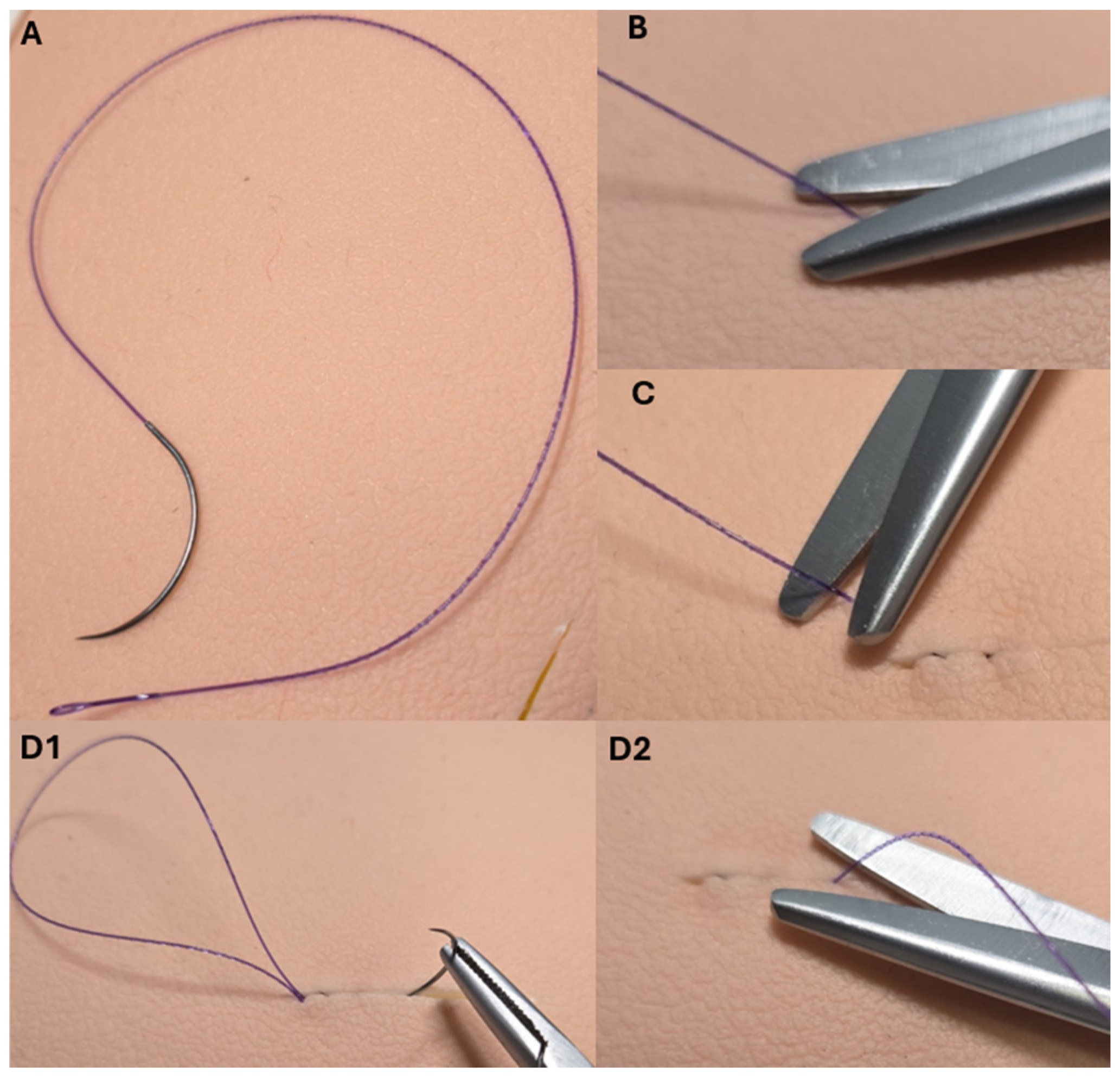

4.3. Practical Solutions to Prevent SBOs Secondary to Barbed Sutures

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beckmann, J.H.; Kersebaum, J.-N.; von Schönfels, W.; Becker, T.; Schafmayer, C.; Egberts, J.H. Use of barbed sutures in robotic bariatric bypass surgery: A single-center case series. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabile, G.; Romano, F.; De Santo, D.; Sorrentino, F.; Nappi, L.; Cracco, F.; Ricci, G. Case Report: Bowel Occlusion Following the Use of Barbed Sutures in Abdominal Surgery. A Single-Center Experience and Literature Review. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 626505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, U.M.; Elsetohy, K.A.; Elshaer, H.S. Barbed Versus Conventional Suture: A Randomized Trial for Suturing the Endometrioma Bed After Laparoscopic Excision of Ovarian Endometrioma. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2016, 23, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafermann, J.; Silas, U.; Saunders, R. Efficacy and safety of V-LocTM barbed sutures versus conventional suture techniques in gynecological surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioli, R.; Plotti, F.; Montera, R.; Damiani, P.; Terranova, C.; Oronzi, I.; Luvero, D.; Scaletta, G.; Muzii, L.; Panici, P.B. A new type of absorbable barbed suture for use in laparoscopic myomectomy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2012, 117, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, E.; Wyman, A.; Hahn, L.; Hart, S. Barbed Sutures in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery. Surg. Technol. Int. 2016, 28, 185–191. [Google Scholar]

- Uccella, S.; Ceccaroni, M.; Cromi, A.; Malzoni, M.; Berretta, R.; De Iaco, P.; Roviglione, G.; Bogani, G.; Minelli, L.; Ghezzi, F. Vaginal cuff dehiscence in a series of 12,398 hysterectomies: Effect of different types of colpotomy and vaginal closure. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 120, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, S.; Nakai, N.; Shiozaki, M.; Ogawa, R.; Sakamoto, M.; Takeyama, H. Use of barbed suture for peritoneal closure in transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2012, 4, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, K.; Tanigawa, N.; Ogata, A.; Nagai, T.; Higashino, M. Laparoscopic Technique and Initial Experiences of Choledocholithotomy Closure With Knotless Unidirectional Barbed Sutures After Surgery for Biliary Stone Disease. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2015, 25, e129–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidarsson, B.; Sundbom, M.; Edholm, D. Shorter overall operative time when barbed suture is used in primary laparoscopic gastric bypass: A cohort study of 25,006 cases. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1484–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, B.; Klingsporn, W.; Lodeiro, C.; Wicker, E.; Christensen, L.; Jones, R.; Tyroch, A. Small bowel obstructions following the use of barbed suture: A review of the literature and analysis of the MAUDE database. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Sampedro, J.J.; Ashrafian, H.; Navarro-Sánchez, A.; Jenkins, J.T.; Morales-Conde, S.; Martínez-Isla, A. Small bowel obstruction due to laparoscopic barbed sutures: An unknown complication? Rev. Esp. Enfermedades Dig. 2015, 107, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picozzi, P.; Nocco, U.; Labate, C.; Gambini, I.; Puleo, G.; Silvi, F.; Pezzillo, A.; Mantione, R.; Cimolin, V. Advances in Robotic Surgery: A Review of New Surgical Platforms. Electronics 2024, 13, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawfal, A.K.; Eisenstein, D.; Theoharis, E.; Dahlman, M.; Wegienka, G. Vaginal cuff closure during robotic-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy: Comparing vicryl to barbed sutures. J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2012, 16, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakiashvili, E.; Bez, M.; Abu Shakra, I.; Ganam, S.; Bickel, A.; Merei, F.; Drobot, A.; Bogouslavski, G.; Kassis, W.; Khatib, K.; et al. Robotic inguinal hernia repair: Is it a new era in the management of inguinal hernia? Asian J. Surg. 2021, 44, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, S.; Turo, R.; Cross, W. Vesicourethral anastomosis using V-LocTM barbed suture during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2011, 64, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guthrie, G.; Chuang, A.; Faro, J.P.; Ali, V. Unidirectional barbed suture versus interrupted vicryl suture in vaginal cuff healing during robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. J. Robot. Surg. 2014, 8, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambi Gowri, K.; King, M.W. A Review of Barbed Sutures-Evolution, Applications and Clinical Significance. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajtak, R.; Ibraheem, C.; Mori, K. Catastrophic complications of a robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with a barbed suture: Ischaemic bowel. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 2024, rjae145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, S.; Nakanishi, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Ookubo, N.; Tanabe, K.; Masuda, H. Strangulated ileus from barbed suture following robot-assisted radical cystectomy: A case report. Urol. Case Rep. 2022, 40, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahanian, S.A.; Finamore, P.S.; Lazarou, G. Delayed small bowel obstruction after robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 21, e11–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Wada, N.; Morishita, S.; Ohtani, M.; Kitta, T.; Kakizaki, H.; Kohro, D.; Shonaka, T. Postoperative small intestinal obstruction caused by barbed suture after robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. IJU Case Rep. 2024, 7, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Hashmi, A.; Edelman, D.A. Small bowel obstruction caused by self-anchoring suture used for peritoneal closure following robotic inguinal hernia repair. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016, 2016, rjw117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, K.N.; Many, H.R.; Foulke, E.; Smith, L.M. Early Post-operative Mechanical Small Bowel Obstruction Induced by Unidirectional Barbed Suture. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 3937–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, M.; Avedikian, J.; Kim, J.; Haskins, I.; Kothari, V. A295 Beware the Barbs! A Rare Case of Early Small Bowel Obstruction Due to Barbed Suture After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-J.; Chung, H.; Kwon, S.-H.; Cha, S.-D.; Cho, C.-H. New suturing technique for robotic-assisted vaginal cuff closure during single-site hysterectomy. J. Robot. Surg. 2017, 11, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, F.; Remorgida, V.; Venturini, P.L.; Ferrero, S. Unidirectional Barbed Suture versus Continuous Suture with Intracorporeal Knots in Laparoscopic Myomectomy: A Randomized Study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, H.; Hosseini, O.; Taylor, B.R.; Opoku, K.; Dharmarpandi, J.; Dharmarpandi, G.; Obokhare, I. The Effect of Barbed Sutures on Complication Rates Post Colectomy: A Retrospective Case-Matched Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e29484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolo, R.; Campi, R.; Klatte, T.; Kriegmair, M.C.; Mir, M.C.; Ouzaid, I.; Salagierski, M.; Bhayani, S.; Gill, I.; Kaouk, J.; et al. Suture techniques during laparoscopic and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis of peri-operative outcomes. BJU Int. 2019, 123, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.H.; Sinchana, T.; Johnston, S.S.; Gunja, N. Trends in adoption of knotless tissue control devices in robotic surgery. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2025, 14, e240229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oor, J.; de Castro, S.; van Wagensveld, B. V-locTM capable of grasping surrounding tissue causes obstruction at the jejunojejunostomy after Roux-en-Y laparoscopic gastric bypass. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2015, 8, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thubert, T.; Pourcher, G.; Deffieux, X. Small bowel volvulus following peritoneal closure using absorbable knotless device during laparoscopic sacral colpopexy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2011, 22, 761–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabile, G.; Vona, L.; Carlucci, S.; Nappi, L. Small bowel obstruction secondary to barbed sutures: A few more tricks to have fewer complications. ANZ J. Surg. 2024, 95, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosma, E.; Pullens, M.J.; de Vries, J.; Roukema, J.A. The impact of complications on quality of life following colorectal surgery: A prospective cohort study to evaluate the Clavien-Dindo classification system. Color. Dis. 2016, 18, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widmar, M.; Keskin, M.; Strombom, P.D.; Gennarelli, R.L.; Szeglin, B.C.; Smith, J.J.; Nash, G.M.; Weiser, M.R.; Paty, P.B.; Russell, D.; et al. Evaluating the Validity of the Clavien-Dindo Classification in Colectomy Studies: A 90-Day Cost of Care Analysis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2021, 64, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoufalia, Z.; Gefen, R.; Emile, S.H.; Zhou, P.; Silva-Alvarenga, E.; Wexner, S.D. Financial and Inpatient Burden of Adhesion-Related Small Bowel Obstruction: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyasiji, T.; Angelo, S.; Kyriakides, T.C.; Helton, S.W. Small Bowel Obstruction: Outcome and Cost Implications of Admitting Service. Am. Surg. 2010, 76, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filser, J.; Reibetanz, J.; Krajinovic, K.; Germer, C.-T.; Dietz, U.A.; Seyfried, F. Small bowel volvulus after transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair due to improper use of V-LocTM barbed absorbable wire—Do we always “read the instructions first”? Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015, 8, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedTech, J.J. STRATAFIX Sprial Knotless Tissue Control Devices. Availabe online: https://www.jnjmedtech.com/en-US/product/stratafix-spiral-knotless-tissue-control-device (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Bassi, A.; Tulandi, T. Evaluation of total laparoscopic hysterectomy with and without the use of barbed suture. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2013, 35, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Number of Patients | Procedure Performed | Type of Suture | Time to Presentation (Days) and Symptoms | Intraoperative Finding | Treatment | Length of Re-Admission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yajima et al. [20] | 1 | Robot-assisted radical cystectomy | 3-0 V-LocTM (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) | 13 days Lower abdominal pain, distension, vomiting | Fatty appendices of the sigmoid colon small bowel adherent to the barbed suture | Diagnostic laparoscopy and bowel resection | 4 days |

| Vahanian et al. [21] | 2 | Robot-assisted supracervical hysterectomy, sacrocolpopexy, trans obturator sling and cystoscopy | 3-0 V-LocTM (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) | 28 days Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain | Small bowel adherent to the barbed suture | Diagnostic laparoscopy, and the elongated suture was cut | 2 days |

| Robot-assisted supracervical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, sacrocolpopexy with mesh, anterior colporrhaphy and cystoscopy | 3-0 V-LocTM (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) | 21 days Vomiting, abdominal pain | Small bowel adherent to the barbed suture | Diagnostic laparoscopy and removal of barbedsu ture | 6 days | ||

| Pajtak et al. [19] | 1 | Robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy | V-LocTM (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) | 42 days Nausea, vomiting | Ischaemic small bowel adherent to the barbed suture | Diagnostic laparotomy and small bowel resection | 7 days |

| Takagi et al. [22] | 1 | Robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy | 3-0 V-LocTM (CovidienTM, Mansfield, MA, USA) | 4 days Vomiting, abdominal distension | Small bowel entanglement with barbed suture and fatty appendages of the sigmoid colon | Diagnostic laparoscopy, tail of V-Loc detached | 18 days |

| Khan et al. [23] | 1 | Robotic inguinal hernia repair | 2-00 V-LocTM (CovidienTM, Dublin, Ireland) | 3 days Nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, obstipation | Barbed suture adherent to small bowel | Diagnostic laparoscopy, the suture was lysed close to the peritoneum, which led to relief of the obstruction | 2 days |

| Gee et al. [24] | 1 | Robotic lysis of adhesions, bilateral oophorectomy and presacral neurectomy | Unspecified unidirectional barbed suture | 14 days Nausea, vomiting, obstipation | Adhesion containing barbed suture tail to small bowel | Diagnostic laparoscopy and truncation of suture tail | 3 days |

| Omaha et al. [25] | 1 | Robot-assisted laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | Unspecified barbed suture | 5 days Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting | Barbed suture adhered to the distal Roux limb | Diagnostic laparoscopy and truncation of suture tail | Unknown |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pajtak, R.; Mori, K. Small Bowel Obstructions Caused by Barbed Sutures in Robotic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Reprod. Med. 2025, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020011

Pajtak R, Mori K. Small Bowel Obstructions Caused by Barbed Sutures in Robotic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Reproductive Medicine. 2025; 6(2):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020011

Chicago/Turabian StylePajtak, Renata, and Krinal Mori. 2025. "Small Bowel Obstructions Caused by Barbed Sutures in Robotic Surgery: A Systematic Review" Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 2: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020011

APA StylePajtak, R., & Mori, K. (2025). Small Bowel Obstructions Caused by Barbed Sutures in Robotic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Reproductive Medicine, 6(2), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6020011