Recurrent Borderline Ovarian Tumors in the Adolescent Population: Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

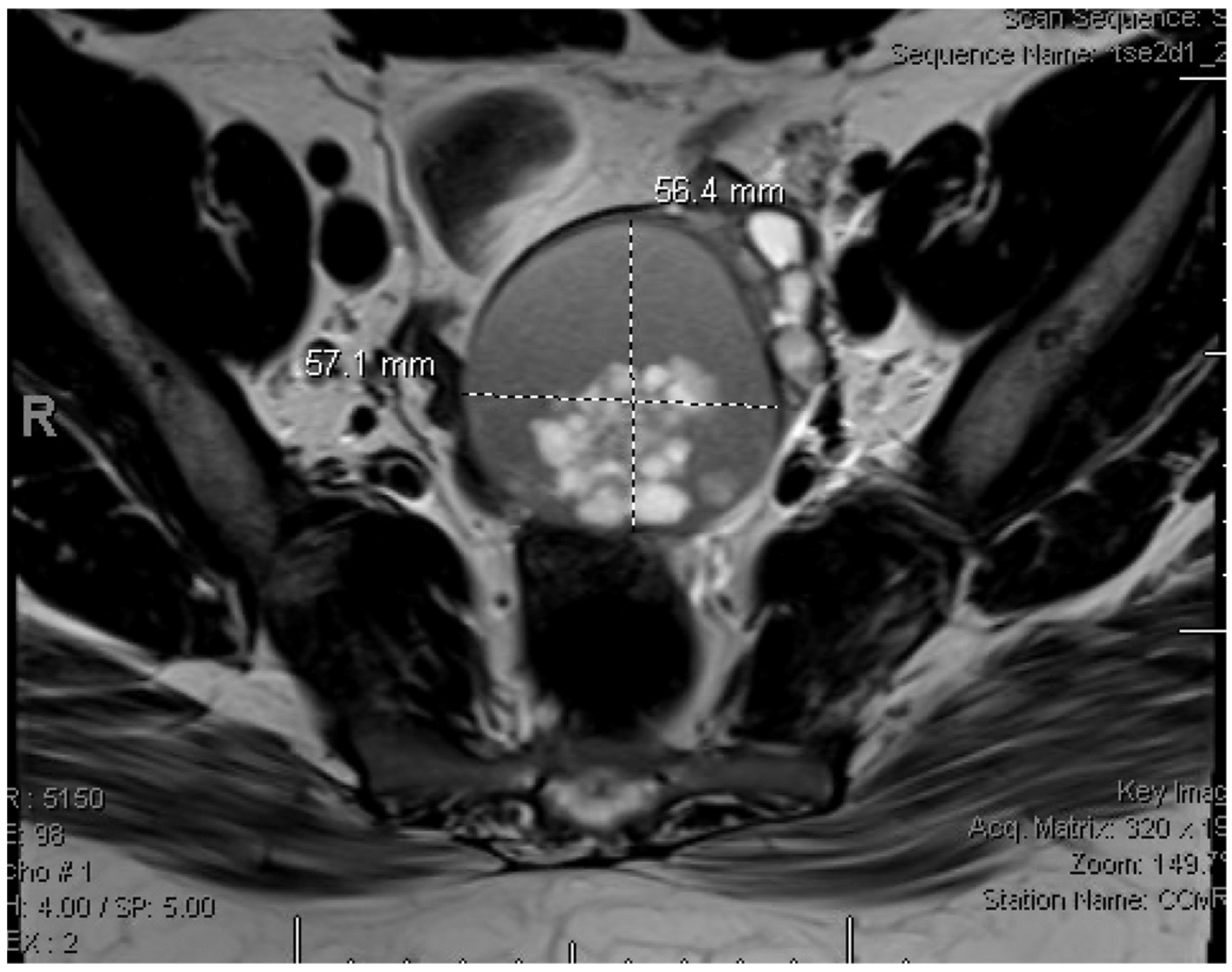

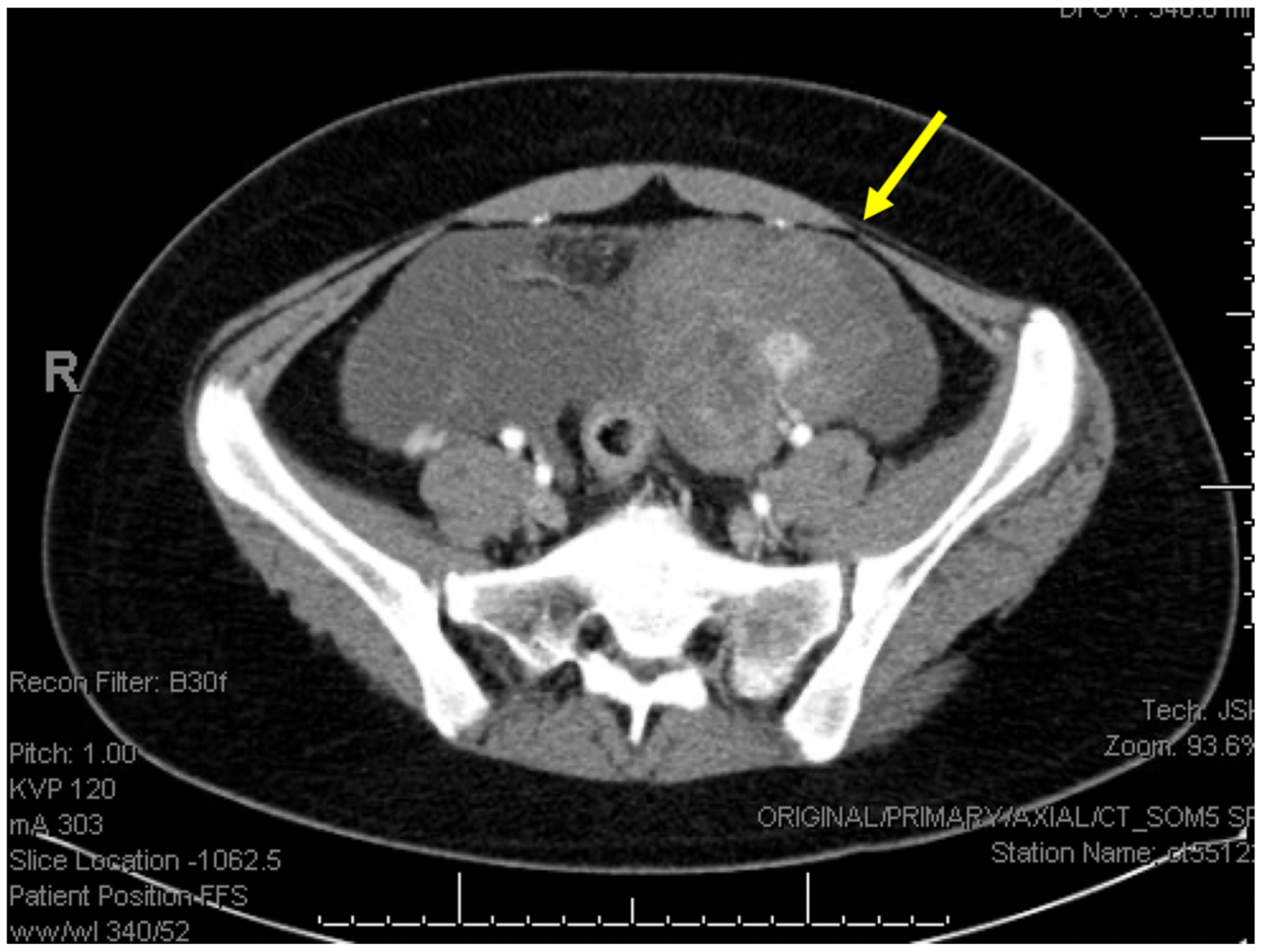

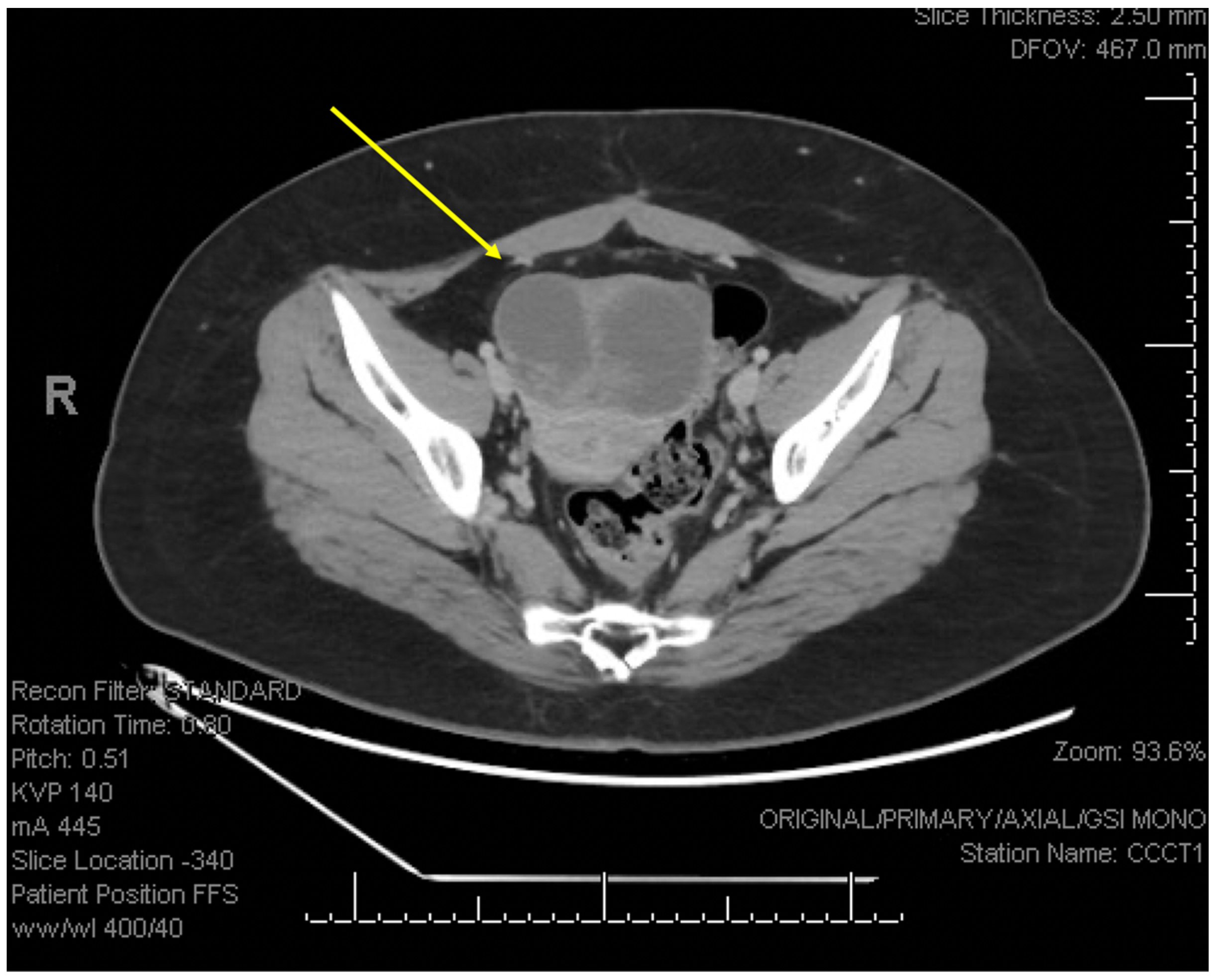

2. Detailed Case Description

3. Discussion

- Surgical management:

- Fertility Considerations:

- Surveillance:

- Hormone Replacement:

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, R.; He, Y.; Jia, C.; Pan, L.; Ma, S.; Wu, M.; Wang, W.; Cheng, X.; et al. Fertility-sparing surgery in children and adolescents with borderline ovarian tumors: A retrospective study. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veran-Taguibao, S.; Taguibao, R.A.A.; Gallegos, N.; Farzaneh, T.; Kim, R.; Lin, F.; Lu, D. A Rare Case of Ovarian Serous Borderline Tumor with Brain Metastasis. Case Rep. Pathol. 2019, 2019, 2954373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischerova, D.; Zikan, M.; Dundr, P.; Cibula, D. Diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of borderline ovarian tumors. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1515–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershenson, D.M. Management of borderline ovarian tumours. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 41, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Wang, B.; Shi, Y. Borderline ovarian tumor in the pediatric and adolescent population: A clinopathologic analysis of fourteen cases. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2020, 13, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, A.; Lucco, K.L.; Lacy, J.; Kives, S.; Gerstle, J.T.; Allen, L. Ovarian epithelial tumors of low malignant potential: A case series of 5 adolescent patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009, 44, 2023–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, K.J.; Patil, N.M.; Muscal, J.A.; Dietrich, J.E.; Venkatramani, R. Borderline Ovarian Tumor in the Pediatric and Adolescent Population: A Case Series and Literature Review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2018, 31, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasaven, L.S.; Chawla, M.; Jones, B.P.; Al-Memar, M.; Galazis, N.; Ahmed-Salim, Y.; El-Bahrawy, M.; Lavery, S.; Saso, S.; Yazbek, J. Fertility Sparing Surgery and Borderline Ovarian Tumours. Cancers 2022, 14, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salani, R.; Backes, F.J.; Fung, M.F.; Holschneider, C.H.; Parker, L.P.; Bristow, R.E.; Goff, B.A. Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanetta, G.; Rota, S.; Chiari, S.; Bonazzi, C.; Bratina, G.; Mangioni, C. Behavior of borderline tumors with particular interest to persistence, recurrence, and progression to invasive carcinoma: A prospective study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 2658–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morice, P.; Uzan, C.; Fauvet, R.; Gouy, S.; Duvillard, P.; Darai, E. Borderline ovarian tumour: Pathological diagnostic dilemma and risk factors for invasive or lethal recurrence. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daraï, E.; Fauvet, R.; Uzan, C.; Gouy, S.; Duvillard, P.; Morice, P. Fertility and borderline ovarian tumor: A systematic review of conservative management, risk of recurrence and alternative options. Human Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskas, M.; Uzan, C.; Gouy, S.; Pautier, P.; Lhommé, C.; Haie-Meder, C.; Duvillard, P.; Morice, P. Prognostic factors of a large retrospective series of mucinous borderline tumors of the ovary (excluding peritoneal pseudomyxoma). Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, D.; Raffone, A.; Zakhari, A.; Maletta, M.; Vizzielli, G.; Restaino, S.; Travaglino, A.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Mabrouk, M.; Casadio, P.; et al. The impact of hysterectomy on oncological outcomes in patients with borderline ovarian tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 165, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, D.; Raffone, A.; Scambia, G.; Maletta, M.; Lenzi, J.; Restaino, S.; Mascilini, F.; Trozzi, R.; Mauro, J.; Travaglino, A.; et al. The impact of hysterectomy on oncological outcomes in postmenopausal patients with borderline ovarian tumors: A multicenter retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1009341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.S.; Mackelvie, M.; Gershenson, D.M.; Ramalingam, P.; Kott, M.M.; Brown, J.; Gauthier, P.; Nugent, E.; Ramondetta, L.M.; Frumovitz, M. Accuracy of Intraoperative Frozen Section Diagnosis of Borderline Ovarian Tumors by Hospital Type. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomba, S.; Zupi, E.; Russo, T.; Falbo, A.; Del Negro, S.; Manguso, F.; Marconi, D.; Tolino, A.; Zullo, F. Comparison of two fertility-sparing approaches for bilateral borderline ovarian tumours: A randomized controlled study. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Pautier, P.; Chopin, N. Tumeurs frontières de l’ovaire. Recommandations pour la pratique clinique du CNGOF–Contraception hormonale et THM/THS après tumeur frontière de l’ovaire [Borderline Ovarian Tumours: CNGOFS Guidelines for Clinical Practice-Hormonal Contraception and MHT/HRT after Borderline Ovarian Tumour]. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2020, 48, 337–340. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, C.; Lambe, M.; Bellocco, R.; Bergfeldt, K.; Riman, T.; Persson, I.; Weiderpass, E. Use of hormone replacement therapy before and after ovarian cancer diagnosis and ovarian cancer survival. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 2907–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fisher, M.; McGough, C.; Darby, J.P. Recurrent Borderline Ovarian Tumors in the Adolescent Population: Case Report. Reprod. Med. 2025, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6010004

Fisher M, McGough C, Darby JP. Recurrent Borderline Ovarian Tumors in the Adolescent Population: Case Report. Reproductive Medicine. 2025; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleFisher, Maya, Christine McGough, and Janelle P. Darby. 2025. "Recurrent Borderline Ovarian Tumors in the Adolescent Population: Case Report" Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6010004

APA StyleFisher, M., McGough, C., & Darby, J. P. (2025). Recurrent Borderline Ovarian Tumors in the Adolescent Population: Case Report. Reproductive Medicine, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6010004