Pott’s Puffy Tumor: Two-Case Series and Contemporary Management Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Reports

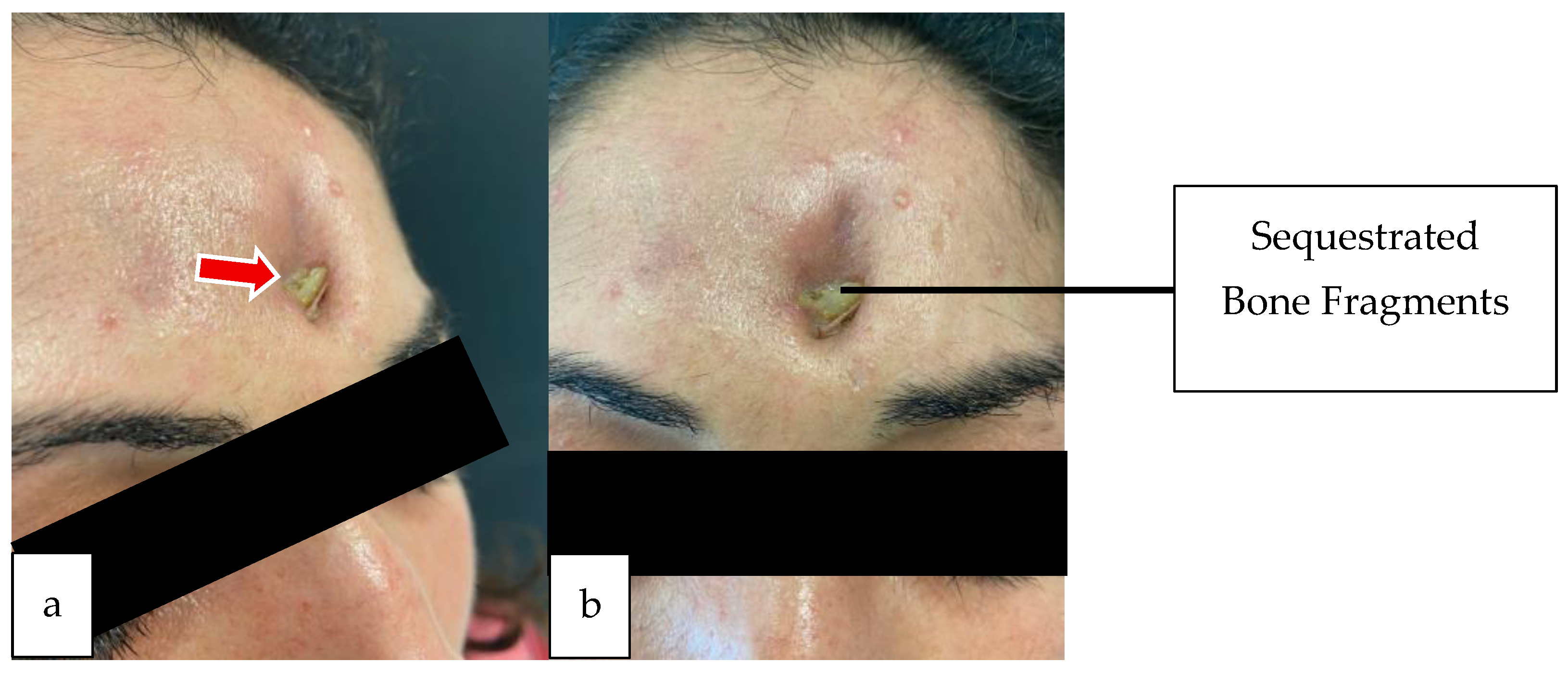

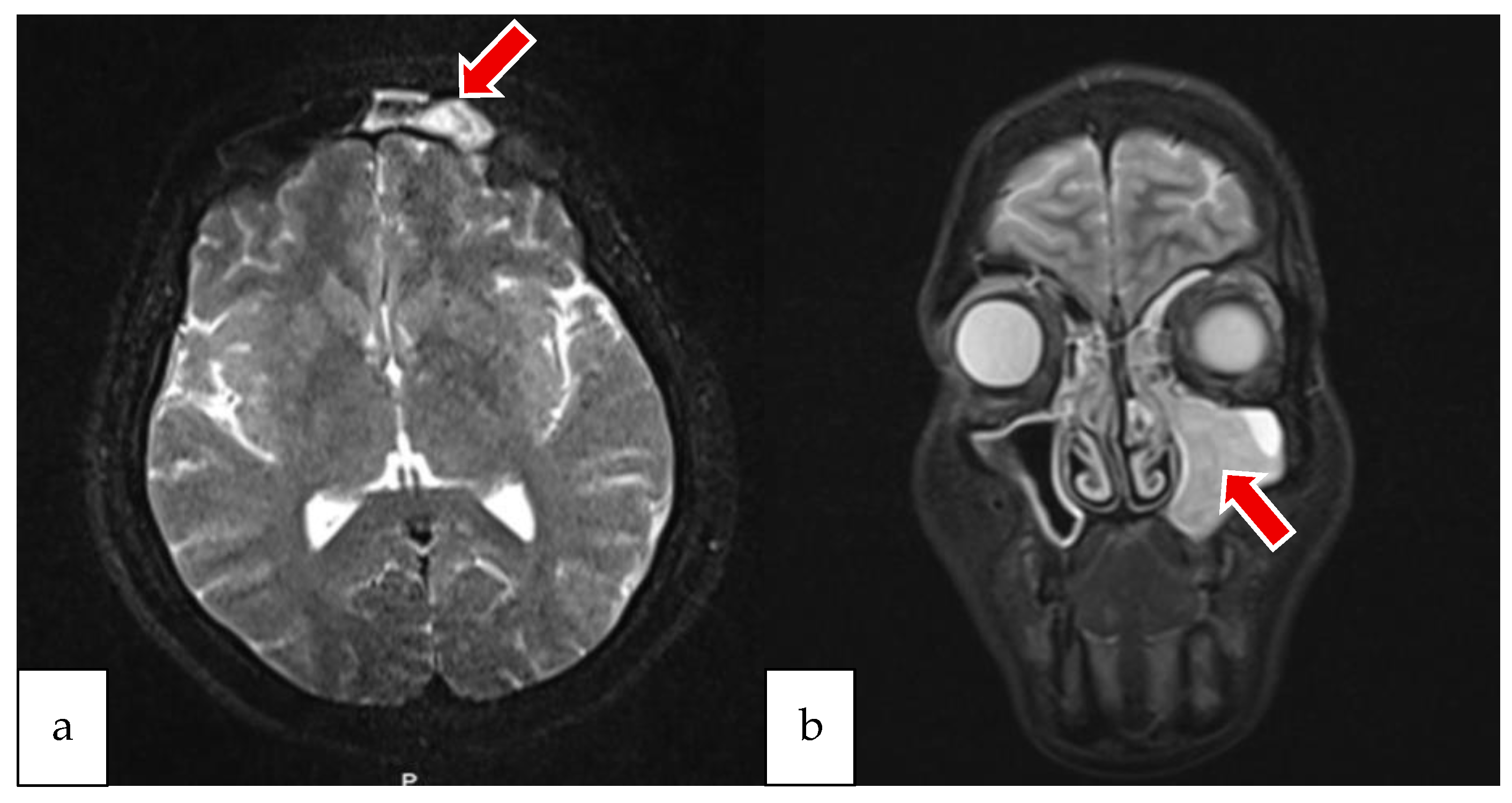

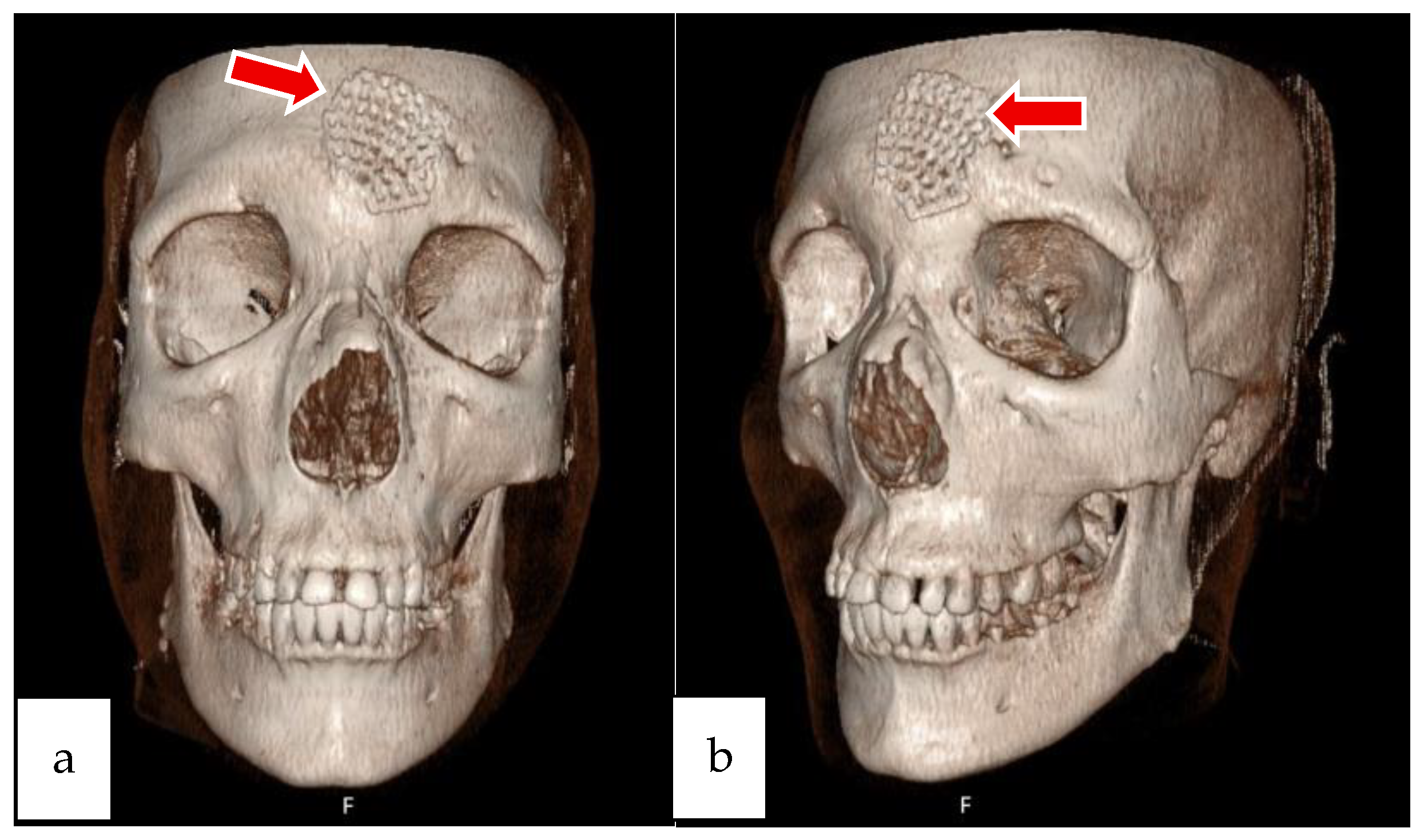

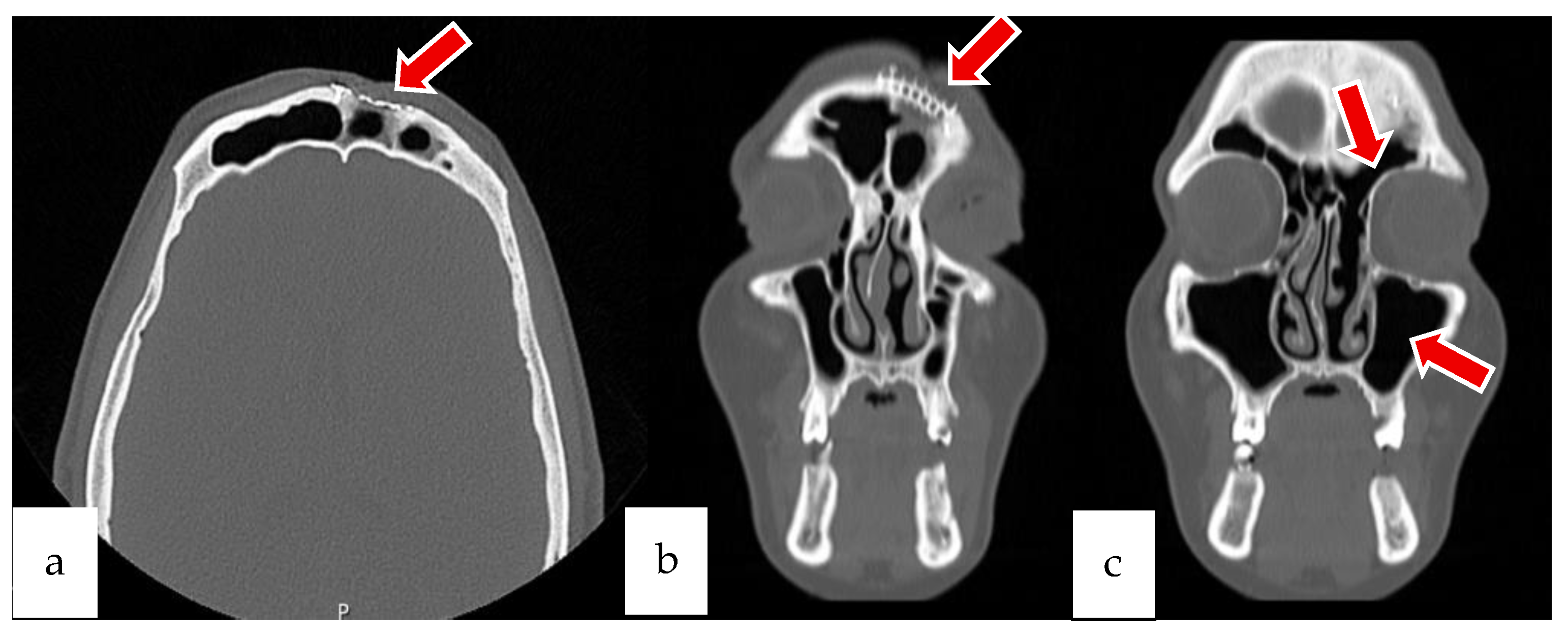

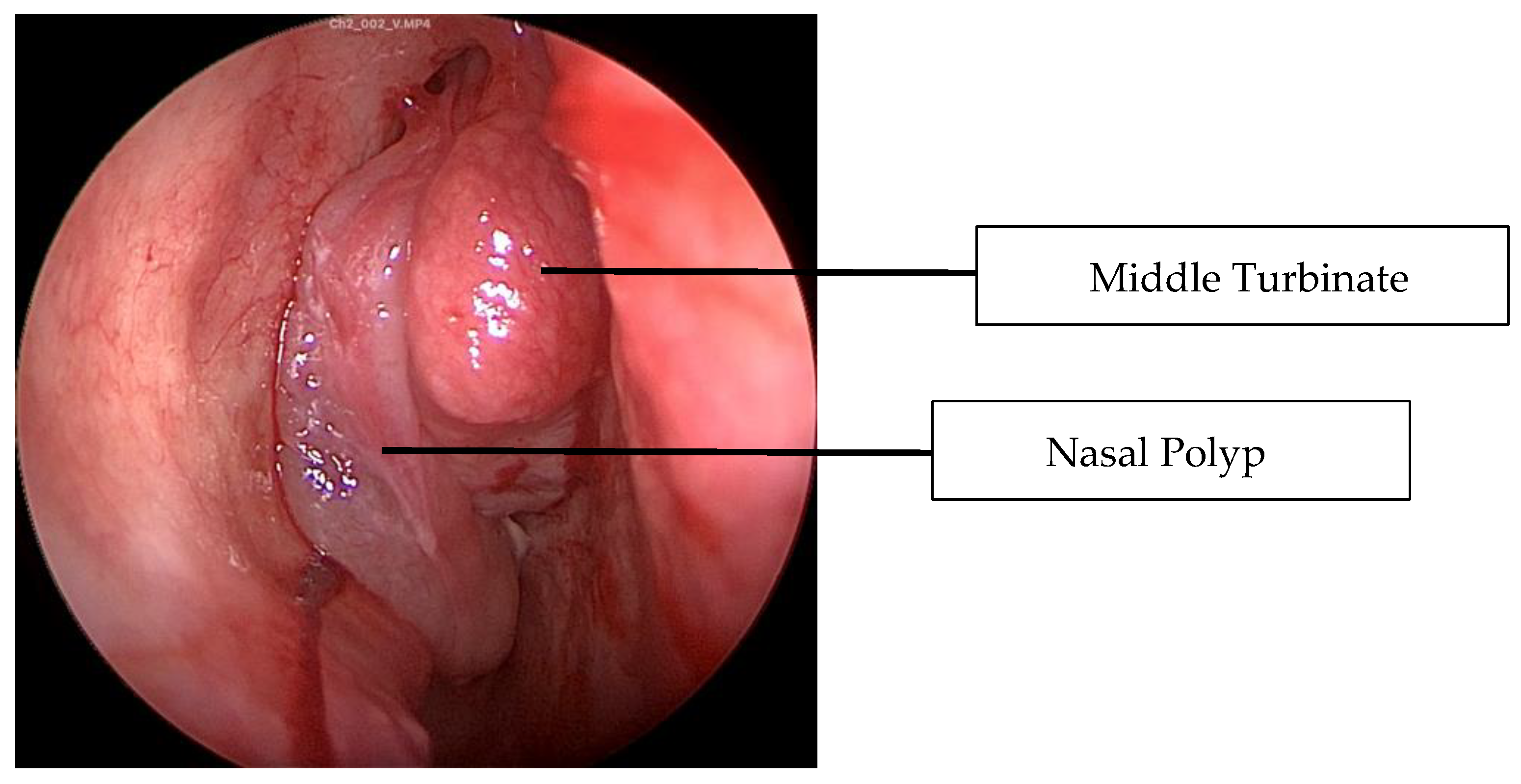

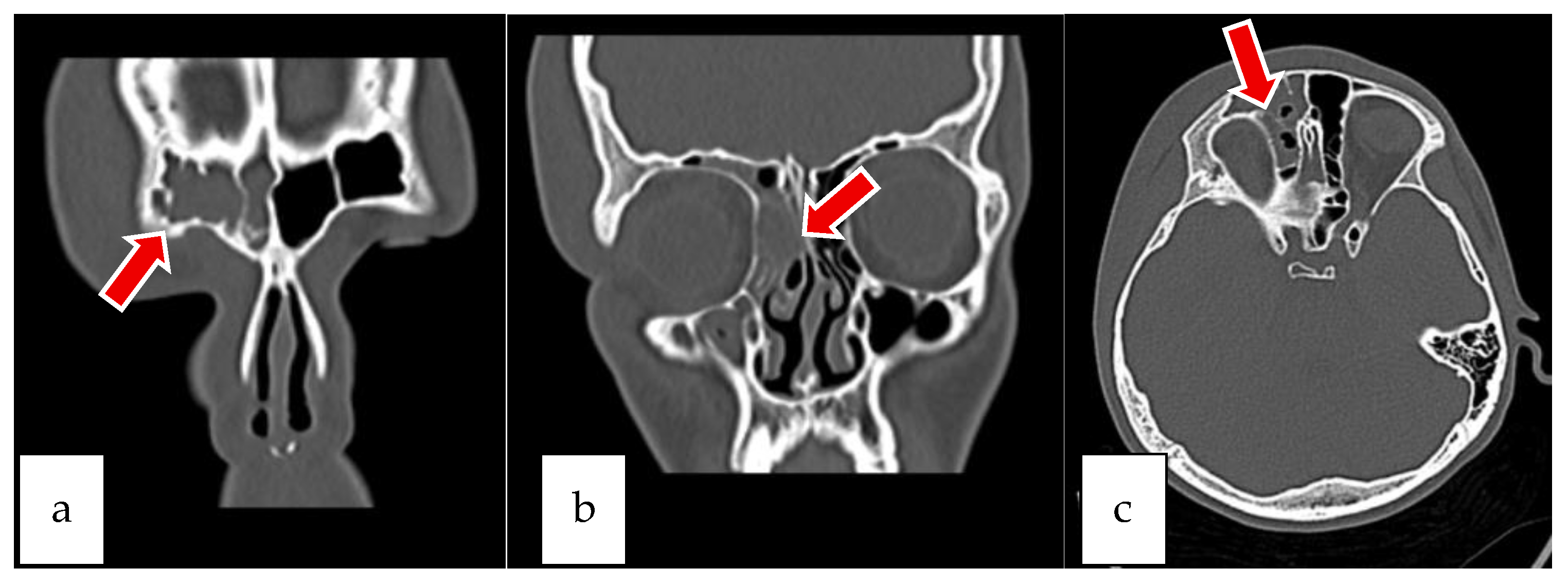

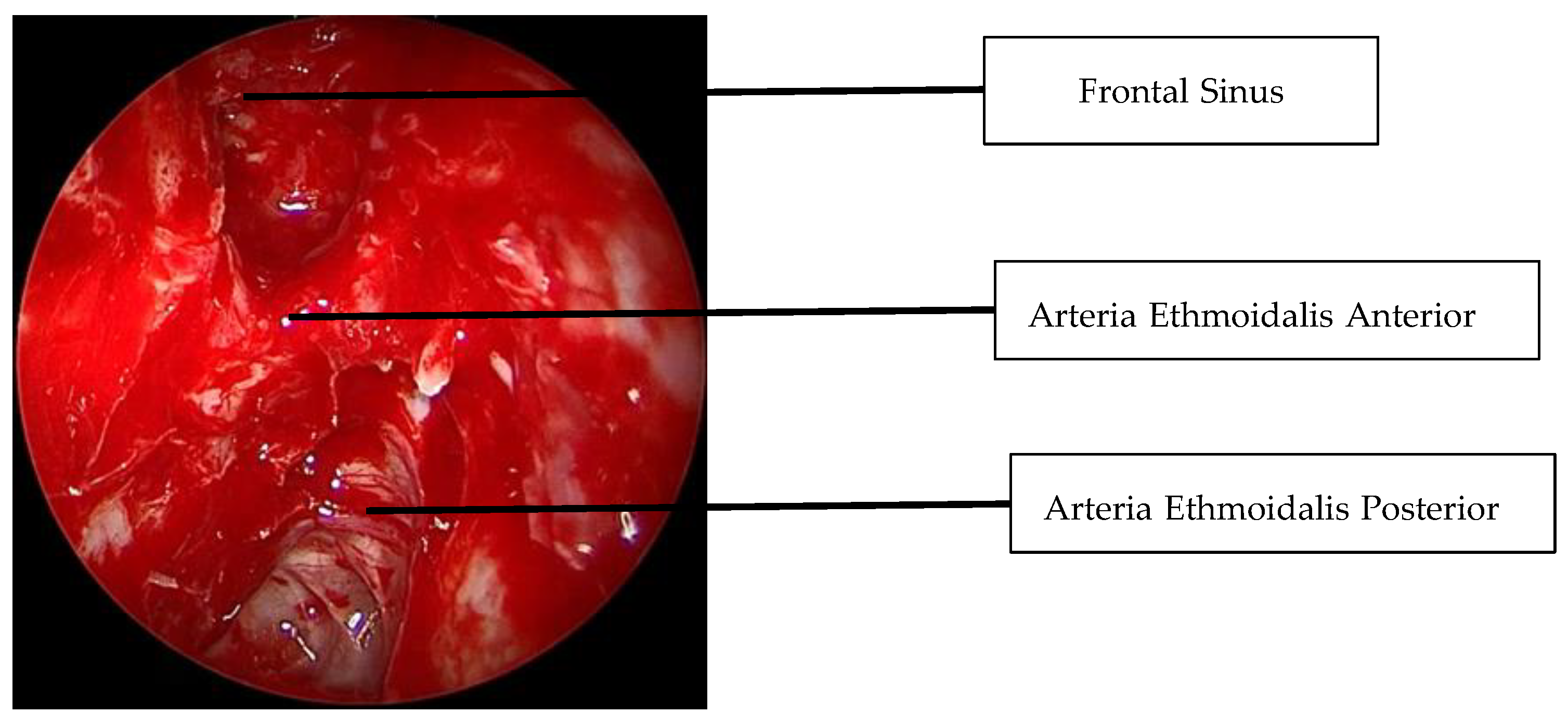

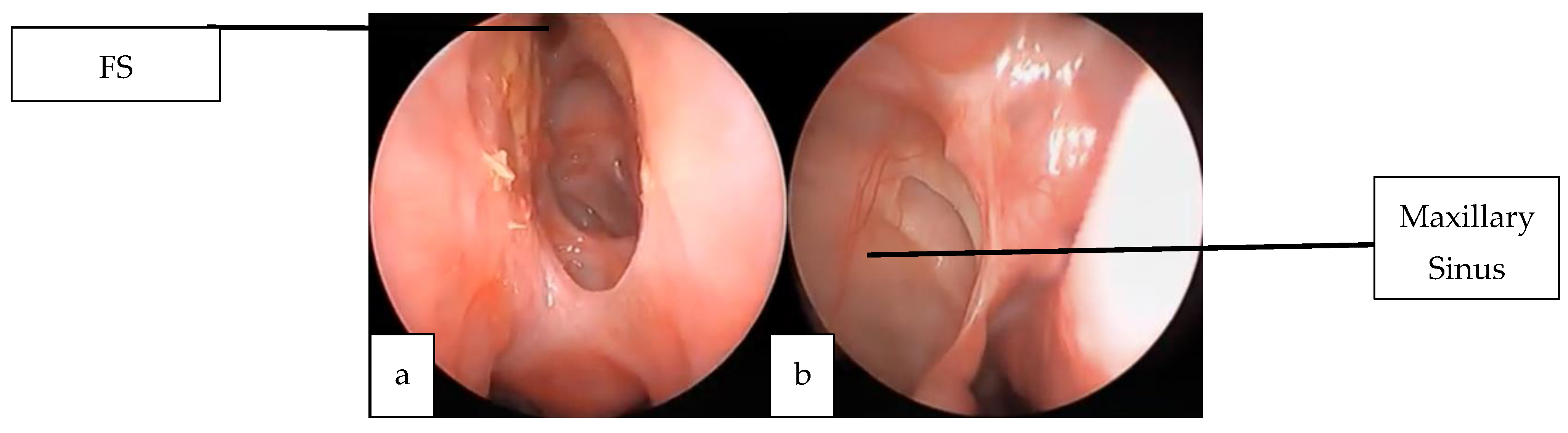

2.1. Case 1

2.2. Case 2

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRS | Chronic Rhinosinusitis |

| PPT | Pott’s Puffy Tumor |

| CRSwNP | Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyp |

| IV | Intravenous |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CT-PNS | Computed tomography of paranasal sinus |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| FESC | Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery |

| FR | Frontal Recess |

| NP | Nasal Polyp |

| WBC | White Blood Cell count |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| Hct | Hematocrit |

| MCV | Mean Corpuscular Volume |

| PLT | Platelet Count |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| IVKM | Intravenous Contrast Material |

| OMK | Ostiomeatal Complex |

| FS | Frontal Sinus |

References

- Tibesar, R.J.; Azhdam, A.M.; Borrelli, M. Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100 (Suppl. S6), 870s–872s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, S.A.; Myriam, L.; Youssef, O.; Sami, R.; Reda, A.; Mohamed, M. Management of a Pott puffy tumor: Case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 123, 110241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, R.L.; North, L.M.; Murray, M.; Khalili, S.; Poetker, D.M. Pott’s puffy tumor: A comprehensive review of the literature. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumfield, E.; Misra, M. Pott’s puffy tumor, intracranial, and orbital complications as the initial presentation of sinusitis in healthy adolescents, a case series. Emerg. Radiol. 2011, 18, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.P.; Wilkie, M.D. Pott’s puffy tumour: An unforgettable complication of frontal sinusitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2014204061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketenci, I.; Unlü, Y.; Tucer, B.; Vural, A. The Pott’s puffy tumor: A dangerous sign for intracranial complications. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 268, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Smith, S.F.; Hammond-Kenny, A. Potts puffy tumour: A rare but important diagnosis. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019, 2019, rjz099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, A.; Milojević, M.; Ivetić, D. A Pott’s Puffy Tumor Associated with Epidural—Cutaneous Fistula and Epidural Abscess: Case Report. Balkan Med. J. 2017, 34, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, L.; Landis, B.N.; Giger, R. Orbital involvement in Pott’s puffy tumor: A systematic review of published cases. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2012, 26, e63–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klivitsky, A.; Erps, A.; Regev, A.; Ashkenazi-Hoffnung, L.; Pratt, L.T.; Grisaru-Soen, G. Pott’s Puffy Tumor in Pediatric Patients: Case Series and Literature Review. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoni, C.M.; Stewart, M.G.; Alford, E.L. Intracranial complications of sinusitis. Laryngoscope 1997, 107, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daloiso, A.; Mondello, T.; Boaria, F.; Savietto, E.; Spinato, G.; Cazzador, D.; Emanuelli, E. Pott’s Puffy Tumor in Young Age: A Systematic Review and Our Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corso, E.; Corbò, M.; Montuori, C.; Furno, D.; Seccia, V.; Di Cesare, T.; Pipolo, C.; Baroni, S.; Mastrapasqua, R.; Rizzuti, A.; et al. Blood and local nasal eosinophilia in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: Prevalence and correlation with severity of disease. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2025, 45, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuki, S.; Tsuda, T.; Takeda, K.; Obata, S.; Inohara, H. A Case of Pott’s Puffy Tumor in a Patient With Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Cureus 2024, 16, e60893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, V.; Yörük, Ö.; Özkan, Ö. Isolated complicated unilateral acute frontal sinusitis of polyp origin obstructing the mouth of the frontonasal duct. ENTCase 2015, 1, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kokot, K.; Fercho, J.M.; Duszyński, K.; Jagieło, W.; Miller, J.; Chasles, O.G.; Yuser, R.; Klecha, M.; Matuszczak, R.; Nowiński, E.; et al. Pott’s Puffy Tumor in the Adult Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case Reports. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bem, L.S., Jr.; Medeiros, M.N.C.; Gadelha, L.d.S.P.N.; Neri, W.J.R.; Cavalcanti, M.A.G. Pott’s Puffy Tumor—Overview of Case Series. J. Meml. Med. 2021, 3, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Terui, H.; Numata, I.; Takata, Y.; Ogura, M.; Aiba, S. Pott’s Puffy Tumor Caused by Chronic Sinusitis Resulting in Sinocutaneous Fistula. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emejulu, J.-K. Complicated Pott’s Puffy Tumour Involving both Frontal and Parietal Bones: A Case Report. J. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2014, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Lee, H.C.; Park, I.H.; Lee, H.M. Endoscopic Endonasal Treatment of a Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 5, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, P.K.; Surianarayanan, G.; Ganeshan, S.; Saxena, S.K. Pott’s puffy tumor in pediatric age group: A retrospective study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 1274–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koci, M.B.; Belen, O.; Kubat, G.O. Pott’s Puffy Tumor: Two-Case Series and Contemporary Management Approach. Sinusitis 2025, 9, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9020022

Koci MB, Belen O, Kubat GO. Pott’s Puffy Tumor: Two-Case Series and Contemporary Management Approach. Sinusitis. 2025; 9(2):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9020022

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoci, Mert Burak, Onur Belen, and Gözde Orhan Kubat. 2025. "Pott’s Puffy Tumor: Two-Case Series and Contemporary Management Approach" Sinusitis 9, no. 2: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9020022

APA StyleKoci, M. B., Belen, O., & Kubat, G. O. (2025). Pott’s Puffy Tumor: Two-Case Series and Contemporary Management Approach. Sinusitis, 9(2), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/sinusitis9020022