1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), colloquially known as 3D printing, has developed into a transformative production technology in recent decades [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In particular, fused deposition modelling (FDM) or fused layer modelling (FLM), a material extrusion method, is characterised by its versatility, user-friendliness, flexibility and cost-efficiency [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9]. This technology enables the tool-free production of three-dimensional components by depositing a molten thermoplastic strand layer by layer [

7,

8,

10]. The main advantages include the ability to create complex geometries, the rapid conversion of digital model data into the final product, and the possibility of component consolidation and functional integration [

3,

5,

7,

10].

Despite these advantages, the mechanical properties of pure polymer FDM components are often limited compared to conventional manufacturing processes [

7,

10,

11]. A key factor here is the anisotropic mechanical behaviour of the components, which is exacerbated by the layer-by-layer build process [

2,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. This manifests itself in different mechanical properties along different axes and, in some cases, significantly lower strength perpendicular to the fibre direction due to the lower interfacial strength compared to the pure matrix [

11,

15]. Frequently occurring defects such as pores and voids, rough surfaces and poor adhesion between the layers or between the fibre and the matrix further impair the mechanical performance [

2,

7,

11,

14,

16,

17]. Polylactide (PLA), acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and nylon are the most commonly used thermoplastics for FDM filaments due to their low melting temperature but are mainly used for concept or prototype models as they have low strength and functional properties in their pure form [

6,

7].

In order to overcome these limitations and improve mechanical properties, the reinforcement of thermoplastics with fibres is increasingly being investigated [

2,

7,

10,

15,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Fibre-reinforced plastics (FRPs) offer superior specific strength and stiffness, corrosion resistance and improved fatigue life [

1,

22]. While short fibre reinforcement (SFRC) can improve tensile strength and Young’s modulus, it often has a negative effect on ductility, toughness and yield strength and increases the porosity of the printed component [

7,

21]. In contrast, continuous fibre reinforced composites (CFRCs) offer significantly higher strength and are of great importance for high-performance applications in aerospace, automotive, marine, sports equipment and medical technology [

2,

7,

16,

18,

20,

23]. Commonly used fibres are carbon fibres, glass fibres and aramid fibres (Kevlar) [

2,

7,

18,

20,

24]. Carbon fibres dominate high-performance applications due to their superior strength-to-weight ratio and high modulus [

2,

18].

FLM printing systems that allow continuous fibres to be integrated into the print layer are currently available on the market. This technology significantly increases the strength and stiffness of components under pure bending stress [

25]. This allows bending strengths and bending stiffnesses similar to those of aluminium alloy 6061 to be achieved in the XY direction [

25].

The reinforcement achieved is limited to the pressure plane, as it is not possible to orient the continuous fibres in the Z direction during the manufacturing process. Consequently, adequate replication of three-dimensional loads is only possible to a limited extent.

A promising strategy for improving the mechanical properties and reducing the anisotropic behaviour of additively manufactured structures is the integration of continuous, unidirectional fibre tapes (UD tapes) [

3,

12]. UD tapes are flat tapes with embedded parallel fibres that offer excellent mechanical strength and stiffness in the longitudinal direction of the fibre [

15,

26]. Combining them with a fused granular fabrication (FGF) process (a form of FLM that processes granules directly) enables faster production and a wider range of usable materials, as the step of prefabricating filaments is eliminated [

12,

17]. This is particularly relevant for large-format additive manufacturing (LFAM) [

12].

However, the effectiveness of UD tape reinforcement depends largely on the quality of the bond between the UD tape and the additively manufactured base structure [

3,

12]. Factors such as the surface quality of the FGF structure, the interface morphology and the parameters of the tape deposition process are crucial here [

3,

12]. Previous studies have shown that even with the same filament composition, different printing results can be achieved and that each parameter combination leads to different results [

6]. A comprehensive visual representation of the various factors that influence the mechanical properties of FDM products is of great importance for their optimisation [

6]. The mechanical properties of continuously fibre-reinforced components depend on a variety of factors and parameters, including the choice of fibre and matrix materials and their orientation in the component [

10].

Despite the growing interest in unidirectional tape reinforcement, there remains a paucity of scientific understanding of the mechanical behaviour of polycarbonate (PC) structures when reinforced with unidirectional tapes in AM processes. A paucity of systematic investigations has been identified in relation to the bonding mechanisms between PC matrices and UD tapes, the resulting interlaminar strength, and the influence of process parameters on anisotropic failure behaviour.

In this context, polycarbonate (PC) is coming into focus as a matrix material for high-performance applications. PC tapes offer excellent adhesive properties [

16], which may be particularly advantageous for achieving strong interfacial bonding with UD tapes.

The central scientific problem that this study aims to address is the current lack of experimentally validated knowledge about the mechanical behaviour, failure mechanisms and interface quality of polycarbonate components reinforced with unidirectional tapes in additive manufacturing. This discrepancy in understanding hinders the reliable design, modelling and optimisation of such hybrid structures for high-performance applications.

4. Discussion

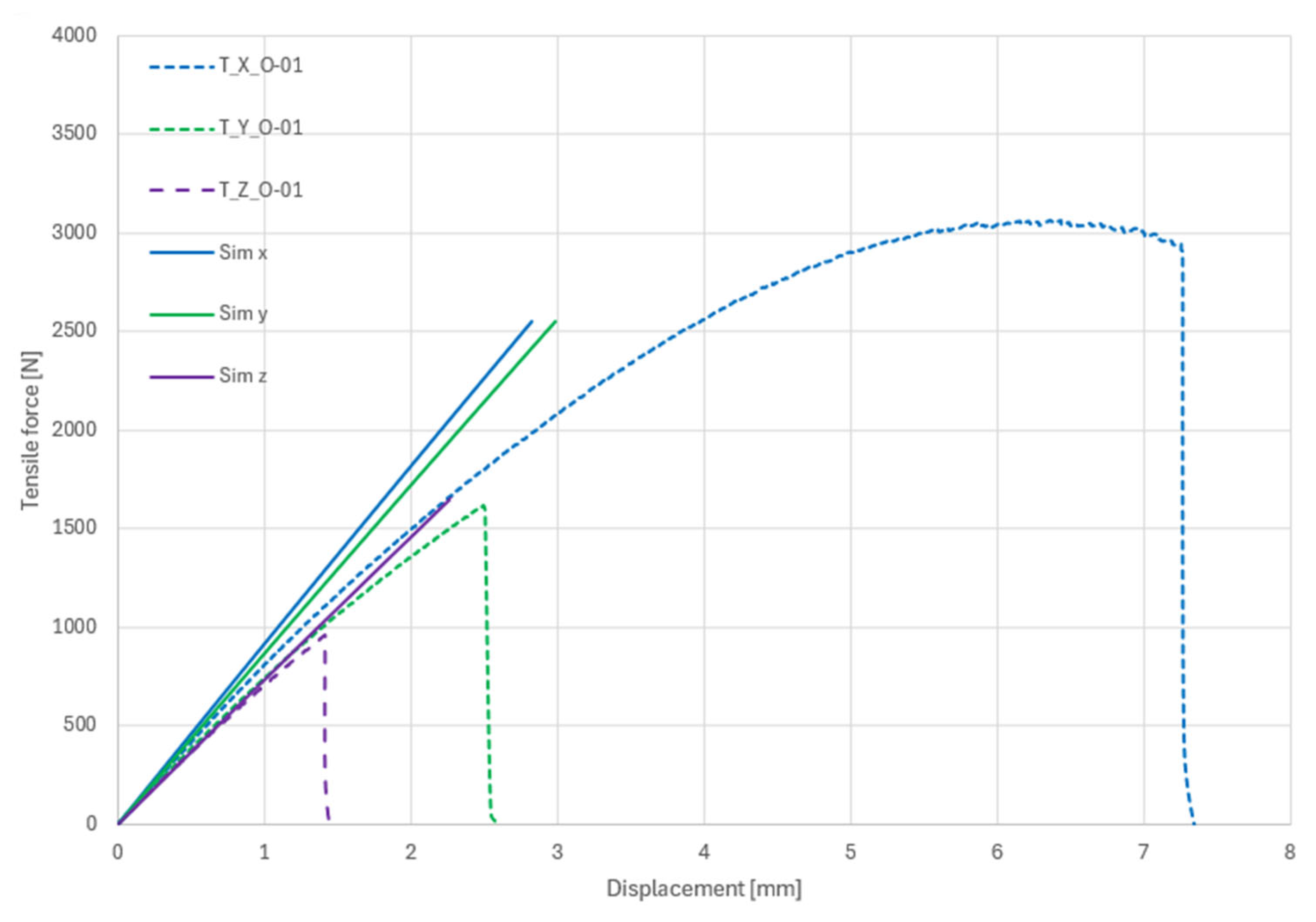

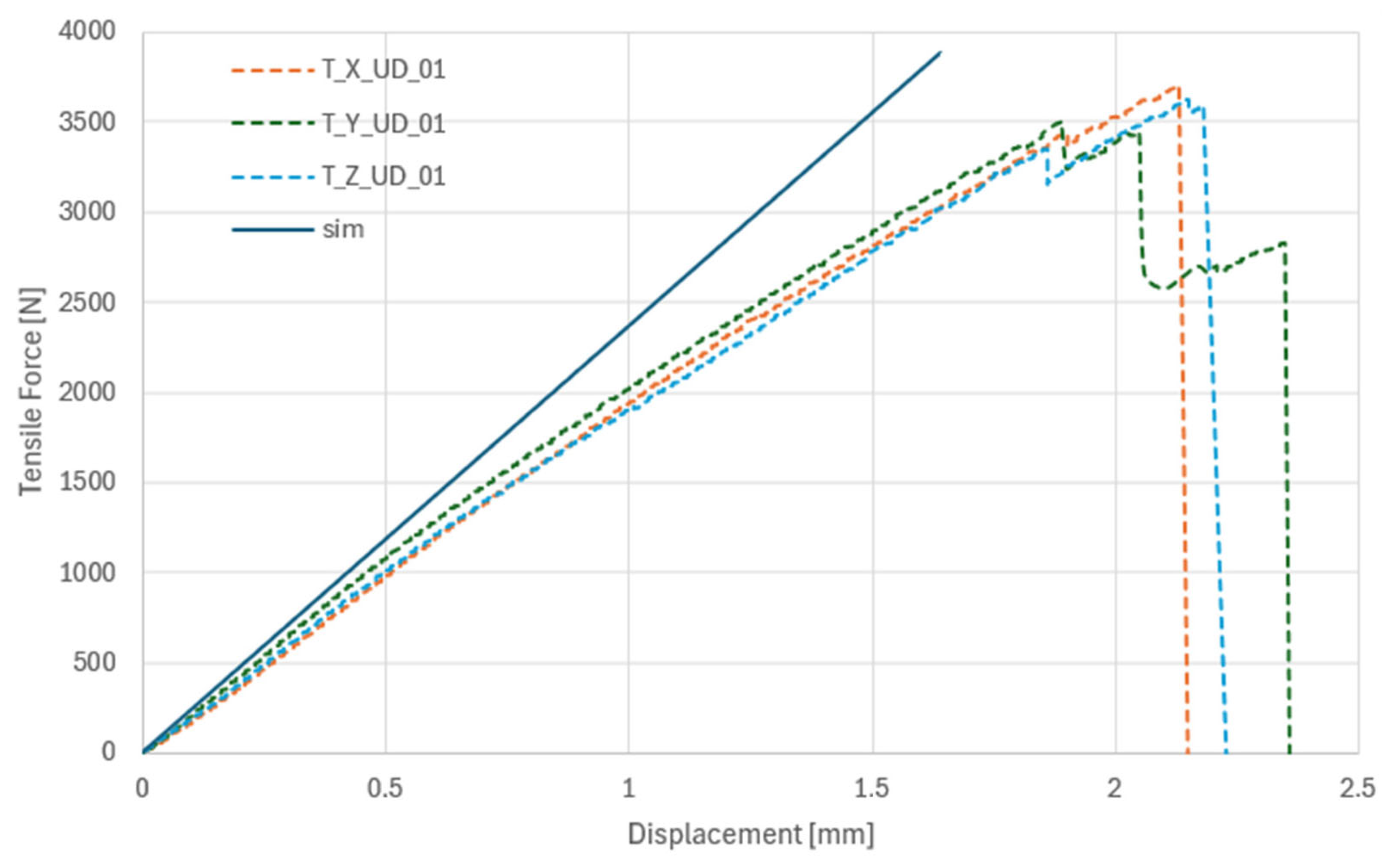

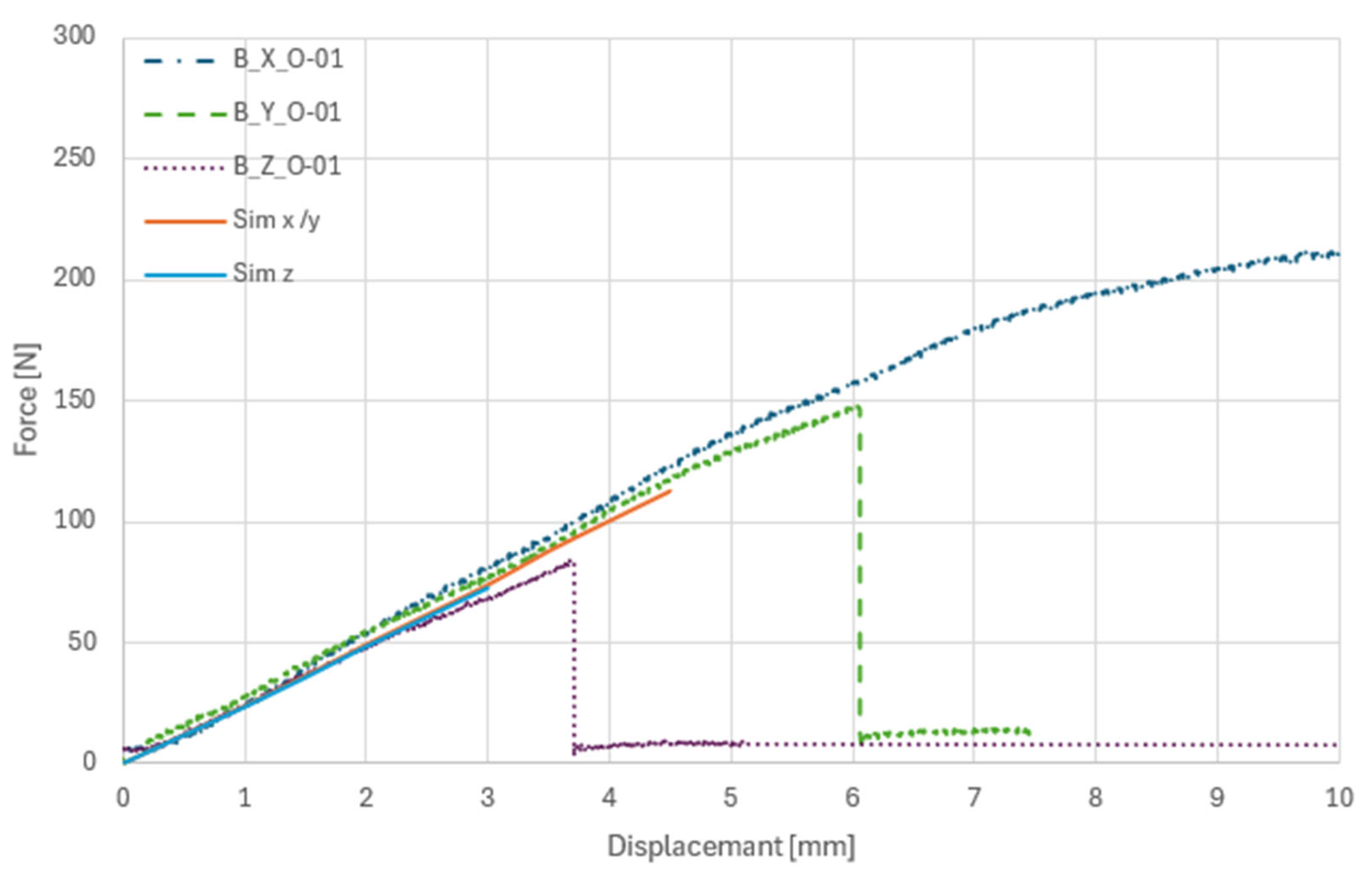

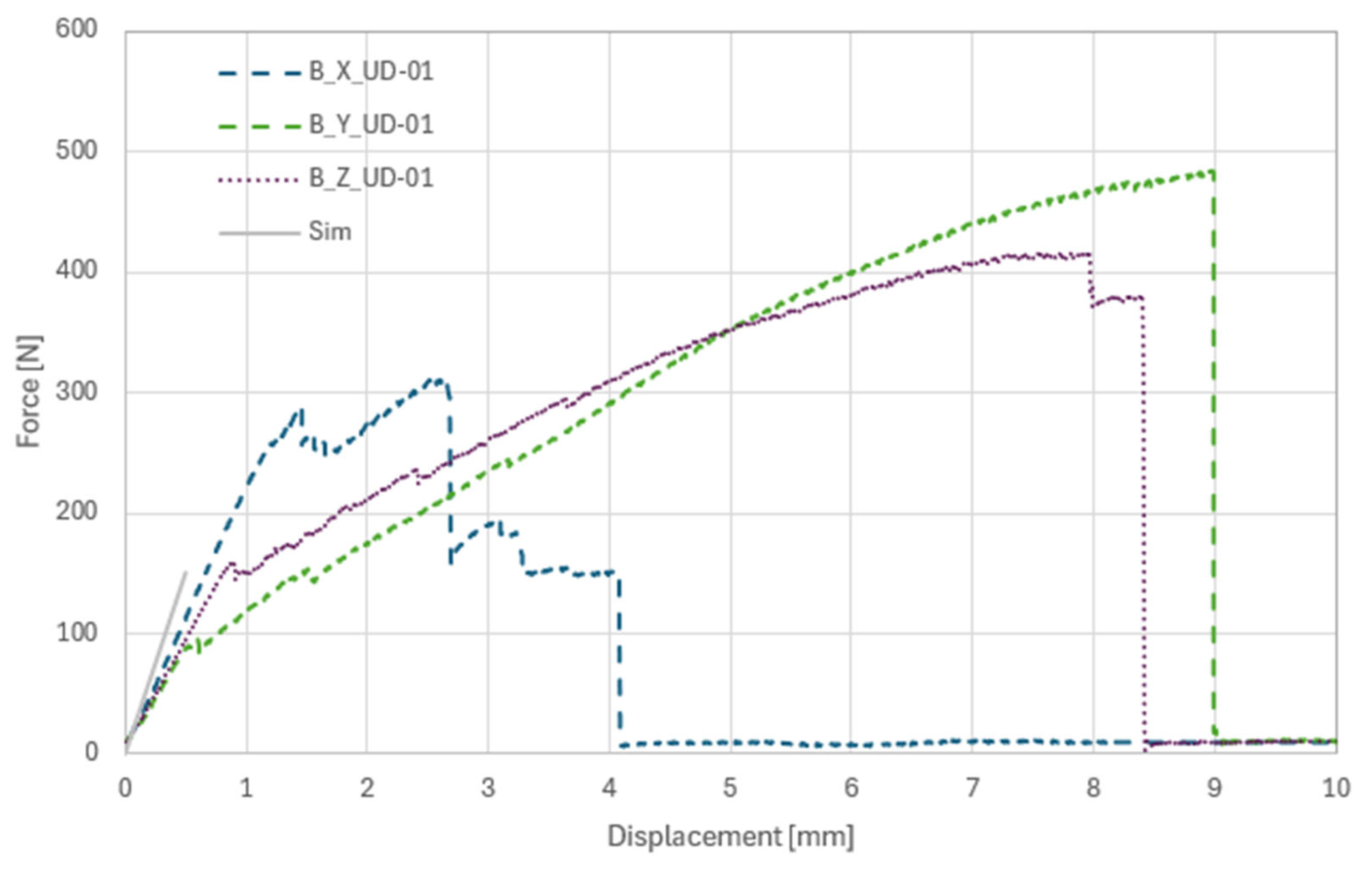

This paper shows that the targeted integration of unidirectional, carbon fibre-reinforced UD tapes into FLM-printed polycarbonate components can significantly improve mechanical properties such as strength and stiffness. The combination of experimental validation and numerical simulation allows for a well-founded assessment of the potential and limitations of this hybrid manufacturing concept.

4.1. Effect of UD Tape Reinforcement

The experimental results demonstrate a substantial increase in stiffness and strength, particularly in the Z direction, which is a significant weak point in classic FLM structures. The load path-oriented integration of the fibre layers partially compensated for weaknesses in layer-by-layer manufacturing. The observed increases of over 400% in tensile and flexural strength, particularly in the Z-direction, underscore the effectiveness of this reinforcement strategy. At the same time, a reduction in deflection and a more brittle failure behaviour were observed, which can be attributed to the high stiffness of the fibre layers.

4.2. Limits of Tape Integration

Despite the proven advantages, the tests also revealed design and process-related challenges. In particular, the adhesion between the UD tape and the FLM matrix proved to be critical for the integrity of the composite. During bending tests on the pressure side, local delamination and buckling occurred, which, due to the nature of the process, can only be reduced by using multiple layers of tape. In addition, manual insertion of the tapes is associated with increased manufacturing tolerances, which leads to greater variation in the strength and stiffness values achieved. Targeted optimisation of the process parameters (e.g., contact pressure, temperature control, bonding strategies) therefore offers additional potential for improving composite quality.

4.3. Validity of Numerical Models

The FEM simulations with orthotropic material approach and application of the Hashin failure criterion proved to be a powerful tool for predicting the structural behaviour of the reinforced components. The high degree of agreement with the experimental results confirms the suitability of the chosen modelling strategy for UD tape-reinforced structures in 3D printing. For the unreinforced specimens, however, the simplified material model proved to be limited, as interlaminar failure mechanisms such as delamination or pore growth could not be adequately captured. However, these effects only occur at higher strains and are of minor importance for the initial stiffness and strength prediction.

4.4. Potential for Technical Applications

The combination of additive manufacturing with continuous fibre reinforcement opens up new possibilities for load-oriented lightweight construction. It should be noted that areas of application arise in particular for housings, connecting elements and structural components that are exposed to high local stresses in several spatial directions. The integration of unidirectional (UD) tapes, which are specifically aligned along the load path, offers a high degree of design freedom and leads to a significant increase in mechanical performance. In particular, types of stress that induce high surface stresses, such as bending, torsional and tensile stresses, benefit greatly from locally adapted UD tape reinforcement. The findings obtained in this work thus form a solid basis for the further development of functionalised and mechanically optimised hybrid components in the field of additive manufacturing.

However, the scalability of the reinforcement approach examined poses a significant challenge, particularly in the case of complex geometries and larger components. The effectiveness of UD tapes depends on the structure of the material. They are most effective in simple structures with clearly defined main stress directions. In contrast, complex components often exhibit multidirectional stress conditions. Purely unidirectional reinforcement addresses these only to a limited extent. This disadvantage can be compensated for by applying several tapes in different orientations. However, it must be taken into account that this significantly increases the manufacturing effort and places high demands on the precise positioning of the reinforcement tapes.

In addition, curved or double-curved surfaces make it difficult to align the fibres without errors, as continuous tapes can only follow three-dimensional contours to a limited extent without creating defects such as wrinkles, fibre bridges or local delamination. Geometry-related irregularities can impair consolidation, reduce effective load transfer and lead to increased dispersion of mechanical characteristics.

The analysis shows that the reinforcement approach is highly suitable for simple, predominantly uniaxially loaded components, whereas its transferability to complex, multidirectionally loaded or large-format structures is limited. Further investigations and the use of automated, geometry-sensitive consolidation and tape application processes are therefore necessary for reliable scaling.

5. Conclusions

In this work, the mechanical properties of polycarbonate components manufactured using FLM technology were investigated, both with and without unidirectional (UD) carbon fiber tape reinforcement. From a scientific perspective, it was demonstrated that the integration of UD carbon fiber tapes along the load-bearing paths significantly increases mechanical performance, particularly in the otherwise weak Z-direction. To this end, systematic tensile and three-point bending tests were performed to determine the relevant parameters, which were subsequently compared with orthotropic FEM simulations in ANSYS ACP. The Hashin failure criterion proved suitable for predicting damage initiation and modeling the failure behavior of the reinforced structures. The significant agreement between experiment and simulation confirms the chosen modeling approaches for hybrid, additively manufactured fiber composite systems and underscores the scientific originality of this work.

From a practical perspective, the study demonstrated that the quality of the tape–matrix bond and the reproducibility of the manufacturing process are crucial factors for the reliability of the composite system. Local delaminations and incomplete adhesion in individual samples highlight the need for targeted process optimizations to ensure consistent mechanical performance. The results of the study support the hypothesis that hybrid additive manufacturing concepts have significant potential for producing mechanically optimized components with industrial relevance.

This opens up several perspectives for future research. Process optimization could, for example, include the implementation of automated pressing mechanisms, local preheating, or in situ control strategies to improve composite quality. The present investigation of alternative matrix materials, such as PEEK or PA6-CF, as well as variable fiber orientations, could enable application-oriented, anisotropic reinforcement. Advanced multiscale simulation approaches, including submodels or cohesive zone simulations, could contribute to optimizing the description of interlaminar failure mechanisms. Ultimately, transferring the insights gained to components with complex geometries and practical loading scenarios—for example, in medical technology, robotics, or lightweight construction—could further demonstrate the applicability and benefits of hybrid additive manufacturing.

This work confirms that the combination of design freedom, targeted reinforcement, and digital simulation offers a promising approach for the load-dependent design of innovative, lightweight structures in industrial applications.