Spiritual Healing: A Triple Scoping Review of the Impact of Spirituality on Burn Injuries, Wounds, and Critical Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Selection of Sources and Evidence

2.4. Synthesis of Results

2.5. Analysis Discrepancies

3. Results

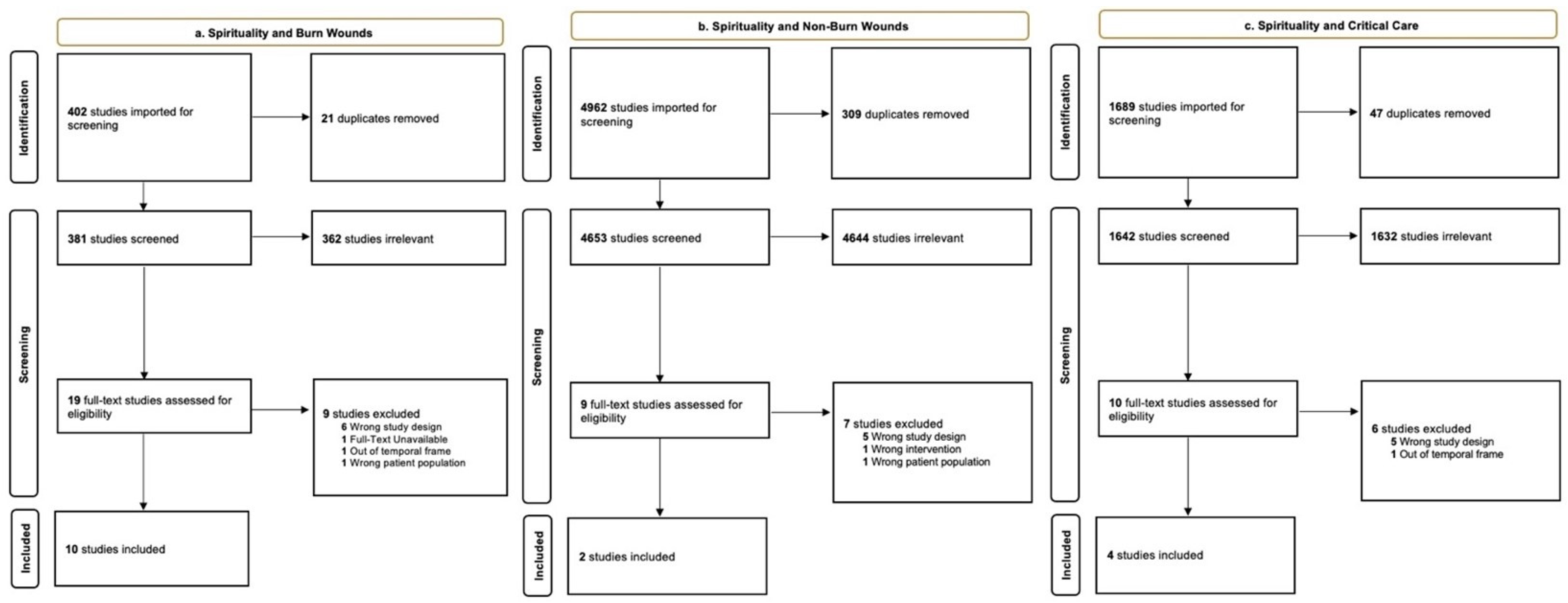

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.1.1. Spirituality and Burn Wounds

3.1.2. Spirituality and Non-Burn Wounds

3.1.3. Spirituality and Critical Care

3.2. Combined Study Outcomes

3.2.1. Spirituality and Burn Wounds

3.2.2. Spirituality and Non-Burn Wounds

3.2.3. Spirituality and Critical Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puchalski, C.M. The role of spirituality in health care. Proc. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. 2001, 4, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Sternthal, M.J. Spirituality, religion and health: Evidence and research directions. Med. J. Aust. 2007, S10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, L.L. Faith, Spirituality, and Religion: A Model for Understanding the Differences. Coll. Stud. Aff. J. 2004, 2004, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, R.; George, K. Spirituality, religion and psychiatry: Its application to clinical practice. Australas. Psychiatry 2006, 4, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechman, S.A.; Patterson, D.R. ABC of burns. Psychosocial aspects of burn injuries. BMJ 2004, 7462, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marucha, P.T.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Favagehi, M. Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosom. Med. 1998, 3, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Marucha, P.T.; Malarkey, W.B.; Mercado, A.M.; Glaser, R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet 1995, 8984, 1194–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole-King, A.; Harding, K.G. Psychological factors and delayed healing in chronic wounds. Psychosom. Med. 2001, 2, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abrams, T.E.; Ratnapradipa, D.; Tillewein, H.; Lloyd, A.A. Resiliency in burn recovery: A qualitative analysis. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 9, 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.R.; Davey, M.; Klock-Powell, K. Rising from the ashes: Stories of recovery, adaptation and resiliency in burn survivors. Soc. Work Health Care 2003, 4, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoudani, F.; Jafarizadeh, H.; Kazamzadeh, J. Social support and posttraumatic growth in Iranian burn survivors: The mediating role of spirituality. Burns 2019, 3, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, A.; Osgood, P.F.; Breslau, A.J.; Vernon, H.L.; Carr, D.B. Chronic persistent pain after severe burns: A survey of 358 burn survivors. Pain Med. 2002, 1, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keivan, N.; Daryabeigi, R.; Alimohammadi, N. Effects of religious and spiritual care on burn patients’ pain intensity and satisfaction with pain control during dressing changes. Burns 2019, 7, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Bahadori, H.; Heidari, A.; Jafari, A.A.; Amiri, H. Effect of Reciting the Name of God on the Pain and Anxiety Experienced by Burn Patients during Dressing. Health Spiritual. Med. Ethics 2020, 7, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibeen, T.; Mahfooz, M.; Fatima, S. Spiritual Transcendence and Psychological Adjustment: The Moderating Role of Personality in Burn Patients. J. Relig. Health 2018, 5, 1618–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Tremblay, S.M.; Dideon-Hess, E.; Blome-Eberwein, S.A. Yoga for burn survivors: Impact on range of motion, cardiovascular function and quality of life. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 36, S262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, A.; Saritas, S. Effect of yoga nidra on the self-esteem and body image of burn patients. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 35, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, C.S.; Saou, M.A.; Roach, S.T.; Hultman, S.C.; Cairns, B.A.; Massey, S.; Koenig, H.G. To heal and restore broken bodies: A retrospective, descriptive study of the role and impact of pastoral care in the treatment of patients with burn injury. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2014, 3, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, H.; Schwartz, G.E. Rapid Wound Healing: A Sufi Perspective. Semin. Integr. Med. 2004, 3, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese-Bjornstal, D.M.; Wood, K.N.; Wambach, A.J. Exploring Religiosity and Spirituality in Coping With Sport Injuries. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2020, 14, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadak, M.; Ansari, K.A.; Qutub, H.; Al-Otaibi, H.; Al-Omar, O.; Al-Onizi, N.; Farooqi, F.A. The Effect of Listening to Holy Quran Recitation on Weaning Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Study. J. Relig. Health 2019, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinton, M.; Giacomini, M.; Toledo, F.; Rose, T.; Hand-Breckenridge, T.; Boyle, A.; Woods, A.; Clarke, F.; Shears, M.; Sheppard, R.; et al. Experiences and Expressions of Spirituality at the End of Life in the Intensive Care Unit. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 2, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merriam-Webster. Spirituality. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/spirituality (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Pargament, K.I.; Mahoney, A.; Exline, J.J.; Jones, J.W.; Shafranske, E.P. Envisioning an integrative paradigm for the psychology of religion and spirituality. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, Theory, and Research; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, C.M.; Vitillo, R.; Hull, S.K.; Reller, N. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 6, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peteet, J.R.; Balboni, M.J. Spirituality and religion in oncology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 4, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steinhauser, K.E.; Fitchett, G.; Handzo, G.F.; Johnson, K.S.; Koenig, H.G.; Pargament, K.I.; Puchalski, C.M.; Sinclair, S.; Taylor, E.J.; Balboni, T.A. State of the Science of Spirituality and Palliative Care Research Part I: Definitions, Measurement, and Outcomes. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 3, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lormans, T.; de Graaf, E.; van de Geer, J.; van der Baan, F.; Leget, C.; Teunissen, S. Toward a socio-spiritual approach? A mixed-methods systematic review on the social and spiritual needs of patients in the palliative phase of their illness. Palliat. Med. 2021, 6, 1071–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghavi, S.; Afshar, P.F.; Bagheri, T.; Naderi, N.; Amin, A.; Khalili, Y. The Relationship Between Spiritual Health and Quality of Life of Heart Transplant Candidates. J. Relig. Health 2020, 3, 1652–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, M.J.; Puchalski, C.M.; Peteet, J.R. The relationship between medicine, spirituality and religion: Three models for integration. J. Relig. Health 2014, 5, 1586–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. How faith heals: A theoretical model. Explore 2009, 2, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, S.A. Integrating spirituality into critical care: An APN perspective using Roy’s adaptation model. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2010, 3, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.M.; Nagendra, H.R.; Nagarathna Raghuram, C.V.; Chandrashekara, S.; Gopinath, K.S.; Srinath, B.S. Influence of yoga on postoperative outcomes and wound healing in early operable breast cancer patients undergoing surgery. Int. J. Yoga 2008, 1, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeschke, M.G.; Pinto, R.; Kraft, R.; Nathens, A.B.; Finnerty, C.C.; Gamelli, R.L.; Gibran, N.S.; Klein, M.B.; Arnoldo, B.D.; Tompkins, R.G.; et al. Morbidity and survival probability in burn patients in modern burn care. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 4, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdelWahab, M.E.; Sadaka, M.S.; Elbana, E.A.; Hendy, A.A. Evaluation of prognostic factors affecting lenght of stay in hospital and mortality rates in acute burn patients. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2018, 2, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bayou, J.; Agbenorku, P.; Amankwa, R. Study on acute burn injury survivors and the associated issues. J. Acute Dis. 2016, 3, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moi, A.L.; Haugsmyr, E.; Heisterkamp, H. Long-Term Study Of Health And Quality of Life After Burn Injury. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2016, 4, 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, H.G.; Nelson, B.; Shaw, S.F.; Al Zaben, F.; Wang, Z.; Saxena, S. Belief into Action Scale: A Brief but Comprehensive Measure of Religious Commitment. Open J. Psychiatry 2015, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| ≥18 Years of Age | Brain Trauma |

| Inpatient Treatment Setting | Death Prior to Admission |

| Spirituality Assessment/Intervention | Pediatric Studies |

| Burn Injury (Burn Review) | Animal Studies |

| Complex Wound (Wound Review) | Review Articles |

| Critical/Intensive Care (Critical Care Review) | Editorial/Commentary Articles |

| English Language | Publication Date <2000 |

| Author | Year | Design | Location of Study | No. of Patients | %TBSA (Range or Mean) | Spirituality Assessment | Improved Outcomes Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T.E. Abrams et al. [9] | 2018 | Case Series | USA | 8 | 20–98 | Higher Power Belief | • Resilience |

| N. Williams et al. [10] | 2003 | Case Series | USA | 8 | 5–95 | Religious Affiliation | • Resilience |

| F. Ajoudani et al. [11] | 2019 | Cross-Sectional Study | Iran | 50 | 32.90 ± 6.11 | Spiritual Well-Being Scale | • Post-traumatic growth |

| A. Dauber et al. [12] | 2002 | Survey | USA | 358 | 38 ± 22.5 | God, Yoga | • Pain |

| N. Keivan et al. [13] | 2019 | Randomized Control Trial | Iran | 68 | 48.50 ± 17.20 | Spiritual Care Sessions | • Pain |

| M. Nasiri et al. [14] | 2020 | Clinical Trial | Iran | 71 | 29.8 ± 9 | Reciting God’s Name | • Pain • Anxiety |

| T. Jibeen et al. [15] | 2018 | Cross-Sectional Study | Pakistan | 98 | 36.9 ± 19.5 | Spiritual Transcendence Index | • Psychological Distress • Behavioral Traits |

| C. Miller et al. [16] | 2015 | Case Control | USA | 5 | 5–65 | Yoga | • Range of Motion • Quality of Life |

| A. Ozdemir et al. [17] | 2019 | Prospective Cohort | Turkey | 100 | 49.3 ± 13.1 | Yoga | • Self-Esteem • Body Image |

| C.S. Hultman et al. [18] | 2014 | Retrospective Cohort | USA | 314 | 11.8 | Religious Affiliation | • Mortality |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lagziel, T.; Sohail, M.M.; Koenig, H.G.; Janis, J.E.; Poteet, S.J.; Khoo, K.H.; Caffrey, J.A.; Lerman, S.F.; Hultman, C.S. Spiritual Healing: A Triple Scoping Review of the Impact of Spirituality on Burn Injuries, Wounds, and Critical Care. Eur. Burn J. 2022, 3, 188-196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010016

Lagziel T, Sohail MM, Koenig HG, Janis JE, Poteet SJ, Khoo KH, Caffrey JA, Lerman SF, Hultman CS. Spiritual Healing: A Triple Scoping Review of the Impact of Spirituality on Burn Injuries, Wounds, and Critical Care. European Burn Journal. 2022; 3(1):188-196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleLagziel, Tomer, Malik Muhammad Sohail, Harold G. Koenig, Jeffrey E. Janis, Stephen J. Poteet, Kimberly H. Khoo, Julie A. Caffrey, Sheera F. Lerman, and Charles S. Hultman. 2022. "Spiritual Healing: A Triple Scoping Review of the Impact of Spirituality on Burn Injuries, Wounds, and Critical Care" European Burn Journal 3, no. 1: 188-196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010016

APA StyleLagziel, T., Sohail, M. M., Koenig, H. G., Janis, J. E., Poteet, S. J., Khoo, K. H., Caffrey, J. A., Lerman, S. F., & Hultman, C. S. (2022). Spiritual Healing: A Triple Scoping Review of the Impact of Spirituality on Burn Injuries, Wounds, and Critical Care. European Burn Journal, 3(1), 188-196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010016