Relations among Stigma, Quality of Life, Resilience, and Life Satisfaction in Individuals with Burn Injuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

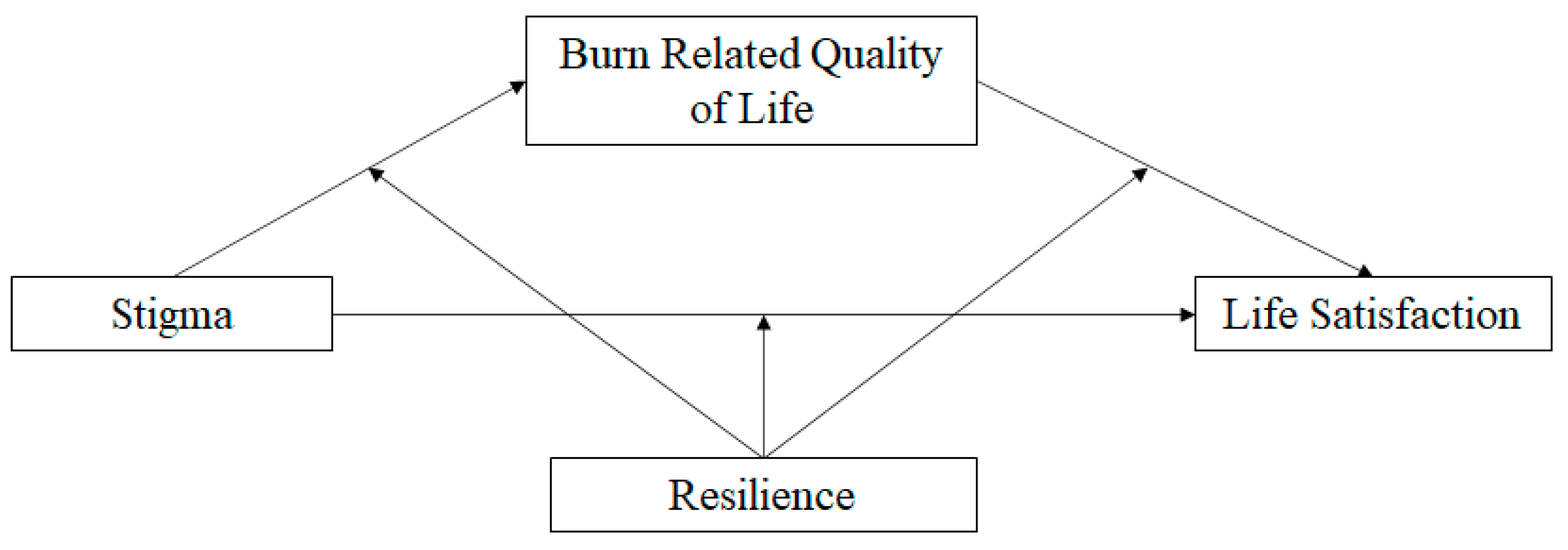

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Mediations

3.1.1. Interpersonal Relationships

3.1.2. Sexuality

3.1.3. Affect

3.1.4. Body Image

3.2. Moderated Mediations

3.2.1. Affect

3.2.2. Body Image

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Burns. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- American Burn Association. Burn Incidence Fact Sheet–American Burn Association. 2016. Available online: https://ameriburn.org/who-we-are/media/burn-incidence-fact-sheet/ (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Knudson-Cooper, M.S. Adjustment to Visible Stigma: The Case of the Severely Burned. Soc. Sci. Med. Part B Med. Anthropol. 1981, 15, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, E.; Crijns, T.J.; Ring, D.; Coopwood, B. Social Factors and Injury Characteristics Associated with the Development of Perceived Injury Stigma among Burn Survivors. Burns 2021, 47, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, M.B.; Lezotte, D.C.; Heltshe, S.; Fauerbach, J.; Holavanahalli, R.K.; Rivara, F.P.; Pham, T.; Engrav, L. Functional and Psychosocial Outcomes of Older Adults After Burn Injury: Results From a Multicenter Database of Severe Burn Injury. J. Burn. Care Res. 2011, 32, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, D.J.; Sutter, M.; Perrin, P.B.; LiBrandi, H.; Feldman, M.J. Coping Styles and Quality of Life in Adults with Burn. Burns 2016, 42, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariello, A.N.; Perrin, P.B.; Tyler, C.M.; Pierce, B.S.; Maher, K.E.; Librandi, H.; Sutter, M.E.; Feldman, M.J. Mediational Models of Pain, Mental Health, and Functioning in Individuals with Burn Injury. Rehabil. Psychol. 2021, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Beekman, J.; Hew, J.; Jackson, S.; Issler-Fisher, A.C.; Parungao, R.; Lajevardi, S.S.; Li, Z.; Maitz, P.K.M. Burn Injury: Challenges and Advances in Burn Wound Healing, Infection, Pain and Scarring. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 123, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.H.; Toland, M.D. Internal Structure and Reliability of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI-29) and Brief Versions (ISMI-10, ISMI-9) among Americans with Depression. Stigma Health 2017, 2, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.A.; da Vila, V.S.C.; Zago, M.M.F.; Ferreira, E. The Stigma of Burns. Burns 2005, 31, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehna, C. Stigma Perspective of Siblings of Children with a Major Childhood Burn Injury. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2013, 25, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariello, A.N.; Tyler, C.M.; Perrin, P.B.; Jackson, B.; Librandi, H.; Sutter, M.; Maher, K.E.; Goldberg, L.D.; Feldman, M.J. Influence of Social Support on the Relation between Stigma and Mental Health in Individuals with Burn Injuries. Stigma Health 2021, 6, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, F. The Effects of Stigma on the Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction of Persons with Mental Illness. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999, 39, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brakel, W.H.; Sihombing, B.; Djarir, H.; Beise, K.; Kusumawardhani, L.; Yulihane, R.; Kurniasari, I.; Kasim, M.; Kesumaningsih, K.I.; Wilder-Smith, A. Disability in People Affected by Leprosy: The Role of Impairment, Activity, Social Participation, Stigma and Discrimination. Glob. Health Action 2012, 5, 18394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, P.N.; Prince, C.R. Perceived Stigma and Community Integration among Clients of Assertive Community Treatment. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2002, 25, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rios, M.D.; Novac, A.; Achauer, B.H. Sexual Dysfunction and the Patient with Burns. J. Burn. Care Rehabil. 1997, 18, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corry, N.; Pruzinsky, T.; Rumsey, N. Quality of Life and Psychosocial Adjustment to Burn Injury: Social Functioning, Body Image, and Health Policy Perspectives. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2009, 21, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, O. Memories of Pain, Adaptation to Life and Early Identification of Stressors in Patients with Burns; ProQuest Information & Learning: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, R.P.; Spence, R.J.; Munster, A.M. Posttraumatic Adaptation and Distress among Adult Burn Survivors. Am. J. Psychiatry 1992, 149, 1234–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Z.; Kausar, R.; Kamran, F. Handling Traumatic Experiences in Facially Disfigured Female Burn Survivors. Burns 2020, 47, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhaber, R.; Bridgman, H.; McLean, L.; Vandervord, J. The Role of Resilience in the Recovery of the Burn-Injured Patient: An Integrative Review. CWCMR 2016, 3, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the Ability to Bounce Back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Cao, R.; Feng, Z.; Guan, H.; Peng, J. The Impacts of Dispositional Optimism and Psychological Resilience on the Subjective Well-Being of Burn Patients: A Structural Equation Modelling Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.H.; Park, J.; Chong, M.K.; Sok, S.R. Factors Influencing Resilience of Burn Patients in South Korea. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Badri, S.; Mellsop, G. Stigma and Quality of Life as Experienced by People with Mental Illness. Australas Psychiatry 2007, 15, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgener, S.C.; Buckwalter, K.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Liu, M.F. The Effects of Perceived Stigma on Quality of Life Outcomes in Persons with Early-Stage Dementia: Longitudinal Findings: Part 2. Dementia 2015, 14, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strine, T.W.; Kroenke, K.; Dhingra, S.; Balluz, L.S.; Gonzalez, O.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The Associations Between Depression, Health-Related Quality of Life, Social Support, Life Satisfaction, and Disability in Community-Dwelling US Adults. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2009, 197, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kildal, M.; Andersson, G.; Fugl-Meyer, A.R.; Lannerstam, K.; Gerdin, B. Development of a Brief Version of the Burn Specific Health Scale (BSHS-B). J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2001, 51, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blades, B.; Mellis, N.; Munster, A. A Burn Specific Health Scale. J. Trauma 1982, 22, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nario-Redmond, M.R.; Noel, J.G.; Fern, E. Redefining Disability, Re-Imagining the Self: Disability Identification Predicts Self-Esteem and Strategic Responses to Stigma. Self Identity 2013, 12, 468–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | (N = 89) |

|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 41.20 (14.45) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 63 (70.80) |

| Female | 26 (29.20) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 63 (70.80) |

| Black | 21 (23.60) |

| Asian/Asian-American | 2 (2.20) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 (1.10) |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic | 1 (1.10) |

| Unknown/Refused | 1 (1.10) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Grade School | 3 (3.40) |

| High School Graduate | 32 (36.00) |

| Some College AA/AS/Technical | 26 (29.20) |

| College Graduate | 19 (21.30) |

| Master’s Degree | 5 (5.60) |

| Doctorate | 3 (3.40) |

| Unknown/Refused | 1 (1.10) |

| Injury Location, n (%) | |

| Hands Only | 29 (32.60) |

| Not on Face or Hands | 28 (31.50) |

| Both Face and Hands | 19 (21.30) |

| Face Only | 5 (5.60) |

| Unknown/Refused | 8 (9.0) |

| Months Since Injury, M (SD) | 4.70 (7.14) |

| Range in months | 1–30 |

| Participants at 1-month post-injury, n (%) | 52 (59.1) |

| Participants within 7 months post-injury, n (%) | 71 (80.7) |

| Total Body Surface Area Burned, n (%) | |

| 0–10% | 52 (58.4) |

| 11–20% | 14 (15.7) |

| 21–30% | 12 (13.5) |

| 31–40% | 4 (4.5) |

| 41–50% | 1 (1.1) |

| 51–60% | 1 (1.1) |

| 61–70% | 1 (1.1) |

| <70% | 1 (1.1) |

| Unknown/Refused | 3 (3.4) |

| Employed Prior to Injury, n (%) | |

| Full-time | 57 (64.0) |

| Unemployed | 20 (22.5) |

| Part-time | 6 (6.70) |

| Student | 3 (3.40) |

| Unknown/Refused | 3 (3.40) |

| Employed at Time of Research, n (%) | |

| Full-time | 44 (49.40) |

| Unemployed | 28 (31.50) |

| Part-time | 4 (4.50) |

| Student | 4 (4.50) |

| Unknown/Refused | 9 (10.10) |

| Stigma to Life Satisfaction Through Burn Related Quality of Life | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Mediation | ||||

| b | p | LCI | UCI | |

| Stigma to Interpersonal | −0.07 | 0.165 | −0.18 | 0.03 |

| Interpersonal to Life Satisfaction | 1.40 | <0.001 | 0.81 | 1.99 |

| Stigma to Life Satisfaction (after Interpersonal) | −0.58 | <0.001 | −0.87 | −0.29 |

| Direct Effect of Stigma | −0.68 | <0.001 | −1.00 | −0.37 |

| Indirect Effect of Stigma | −0.10 | −0.26 | 0.02 | |

| Sexuality Mediation | ||||

| Stigma to Sexuality | −0.07 | 0.191 | −0.18 | 0.04 |

| Sexuality to Life Satisfaction | 0.74 | 0.017 | 0.14 | 1.35 |

| Stigma to Life Satisfaction (after Sexuality) | −0.63 | <0.001 | −0.94 | −0.32 |

| Direct Effect of Stigma | −0.68 | <0.001 | −1.00 | −0.37 |

| Indirect Effect of Stigma | −0.05 | −0.16 | 0.02 | |

| Affect Mediation | ||||

| Stigma to Affect | −0.45 | <0.001 | −0.66 | −0.23 |

| Affect to Life Satisfaction | 0.65 | <0.001 | 0.36 | 0.93 |

| Stigma to Life Satisfaction (after Affect) | −0.40 | 0.014 | −0.71 | −0.08 |

| Direct Effect of Stigma | −0.68 | <0.001 | −1.00 | −0.37 |

| Indirect Effect of Stigma | −0.29 | −0.56 | −0.11 | |

| Body Image Mediation | ||||

| Stigma to Body Image | −0.21 | 0.010 | −0.37 | −0.05 |

| Body Image to Life Satisfaction | 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.36 | 1.15 |

| Stigma to Life Satisfaction (after Body Image) | −0.52 | 0.001 | −0.83 | −0.21 |

| Direct Effect of Stigma | −0.68 | <0.001 | −1.00 | −0.37 |

| Indirect Effect of Stigma | −0.16 | −0.37 | −0.04 | |

| Resilience | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Affect | ||

| 18.00 | −0.21 | −0.45 to −0.05 |

| 23.00 | −0.05 | −0.20 to 0.01 |

| 27.00 | 0.03 | −0.10 to 0.17 |

| Body Image | ||

| 18.00 | −0.02 | −0.17 to 0.09 |

| 23.00 | −0.02 | −0.18 to 0.05 |

| 27.00 | −0.02 | −0.30 to 0.07 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watson, J.D.; Perrin, P.B. Relations among Stigma, Quality of Life, Resilience, and Life Satisfaction in Individuals with Burn Injuries. Eur. Burn J. 2022, 3, 145-155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010012

Watson JD, Perrin PB. Relations among Stigma, Quality of Life, Resilience, and Life Satisfaction in Individuals with Burn Injuries. European Burn Journal. 2022; 3(1):145-155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatson, Jack D., and Paul B. Perrin. 2022. "Relations among Stigma, Quality of Life, Resilience, and Life Satisfaction in Individuals with Burn Injuries" European Burn Journal 3, no. 1: 145-155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010012

APA StyleWatson, J. D., & Perrin, P. B. (2022). Relations among Stigma, Quality of Life, Resilience, and Life Satisfaction in Individuals with Burn Injuries. European Burn Journal, 3(1), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010012