Preliminary Comparative Analysis of Monolithic Zirconia and Hybrid Metal–Ceramic Designs in Full-Arch Implant-Supported Restorations

Abstract

1. Introduction

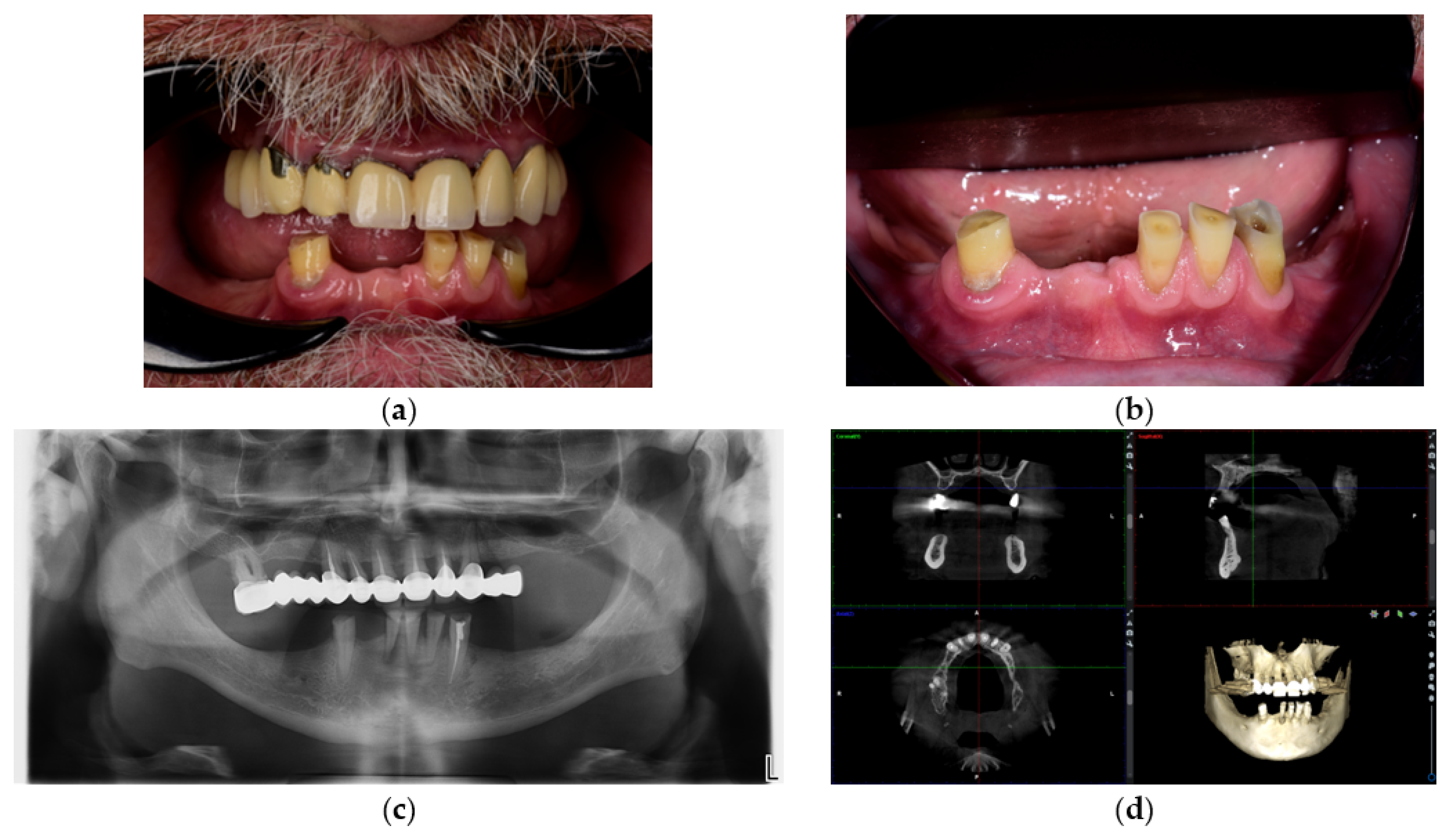

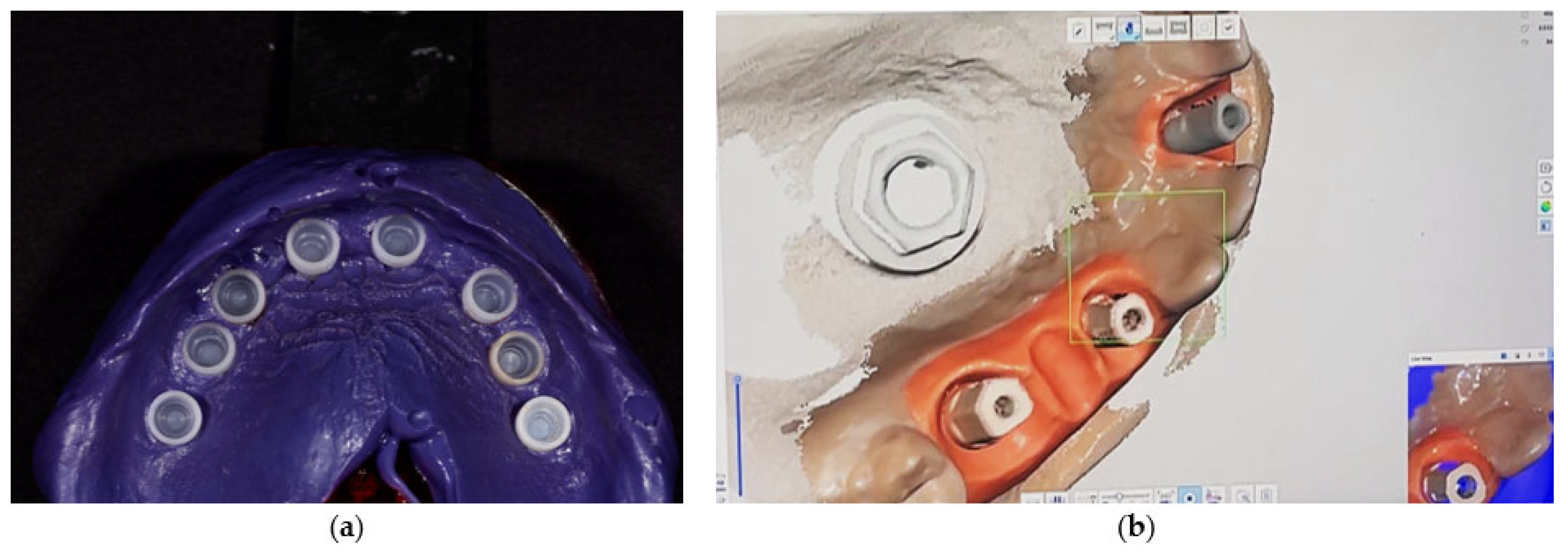

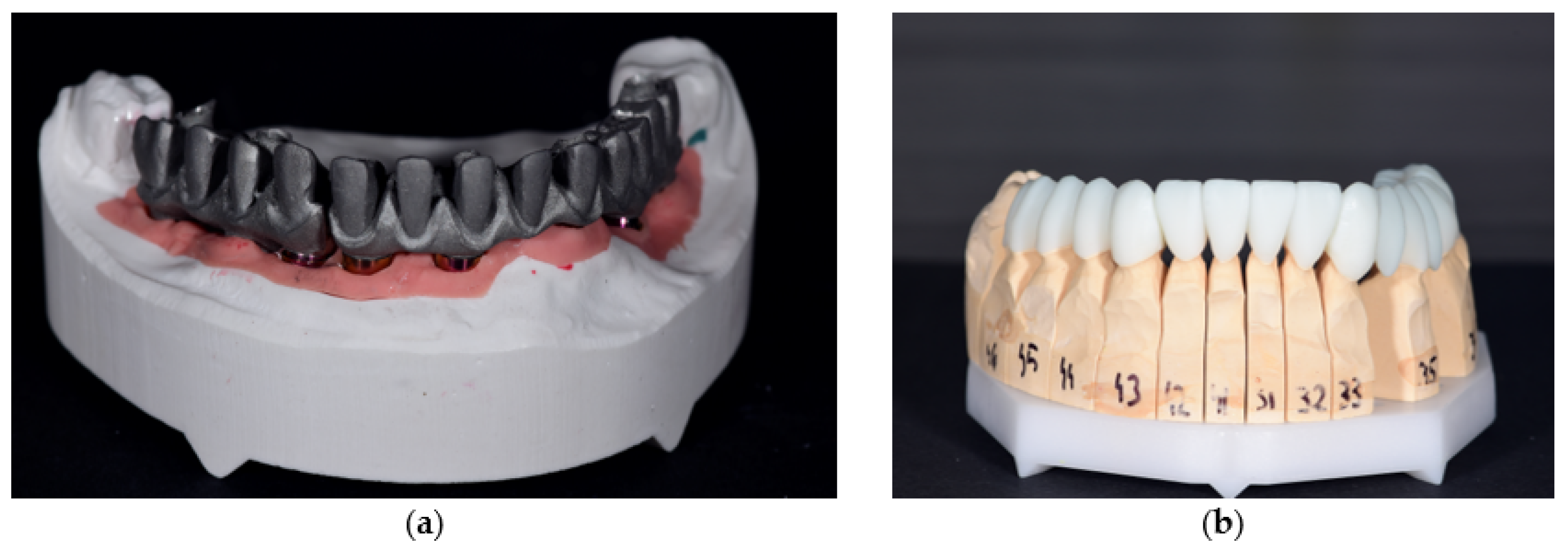

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Patient Selection

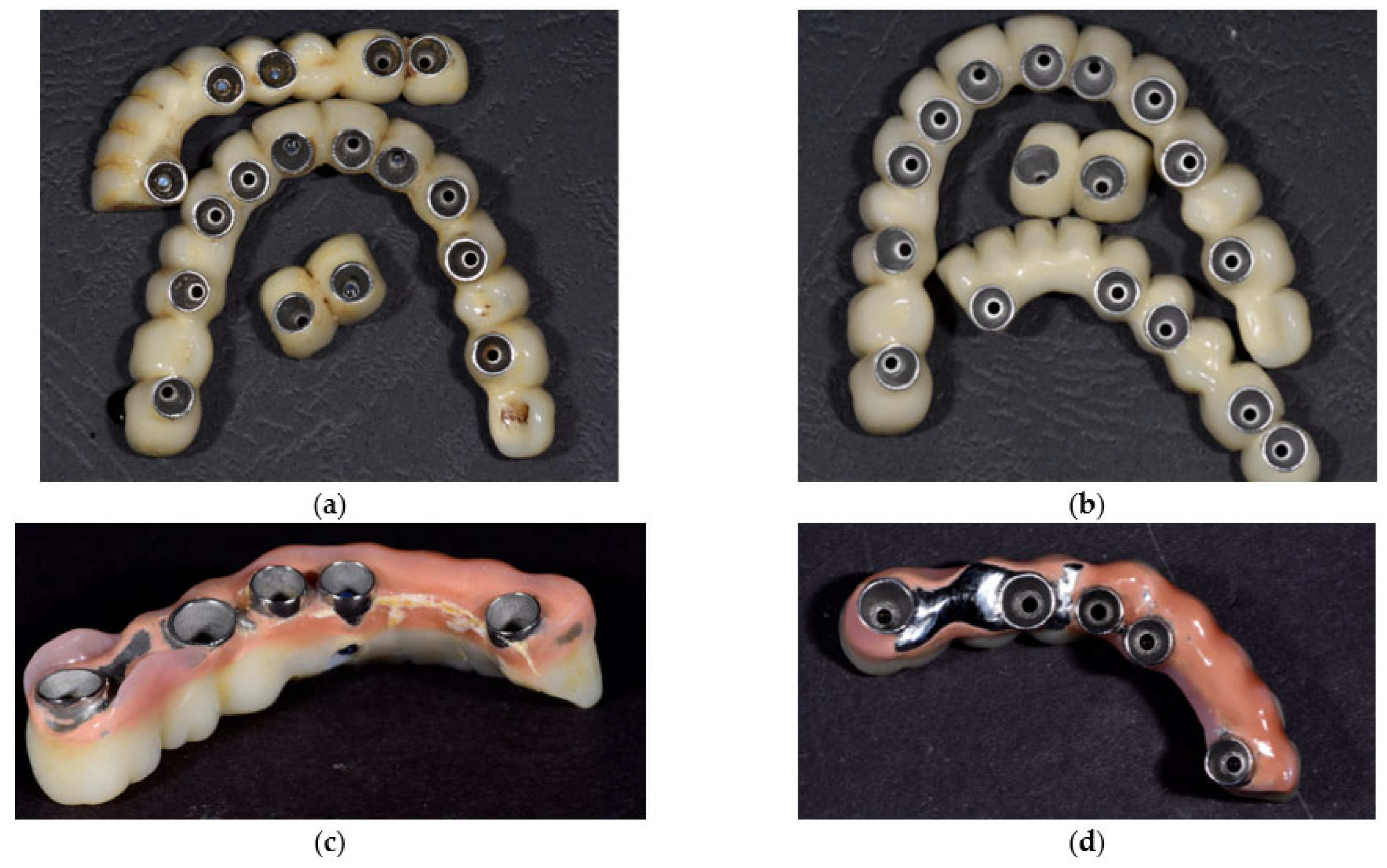

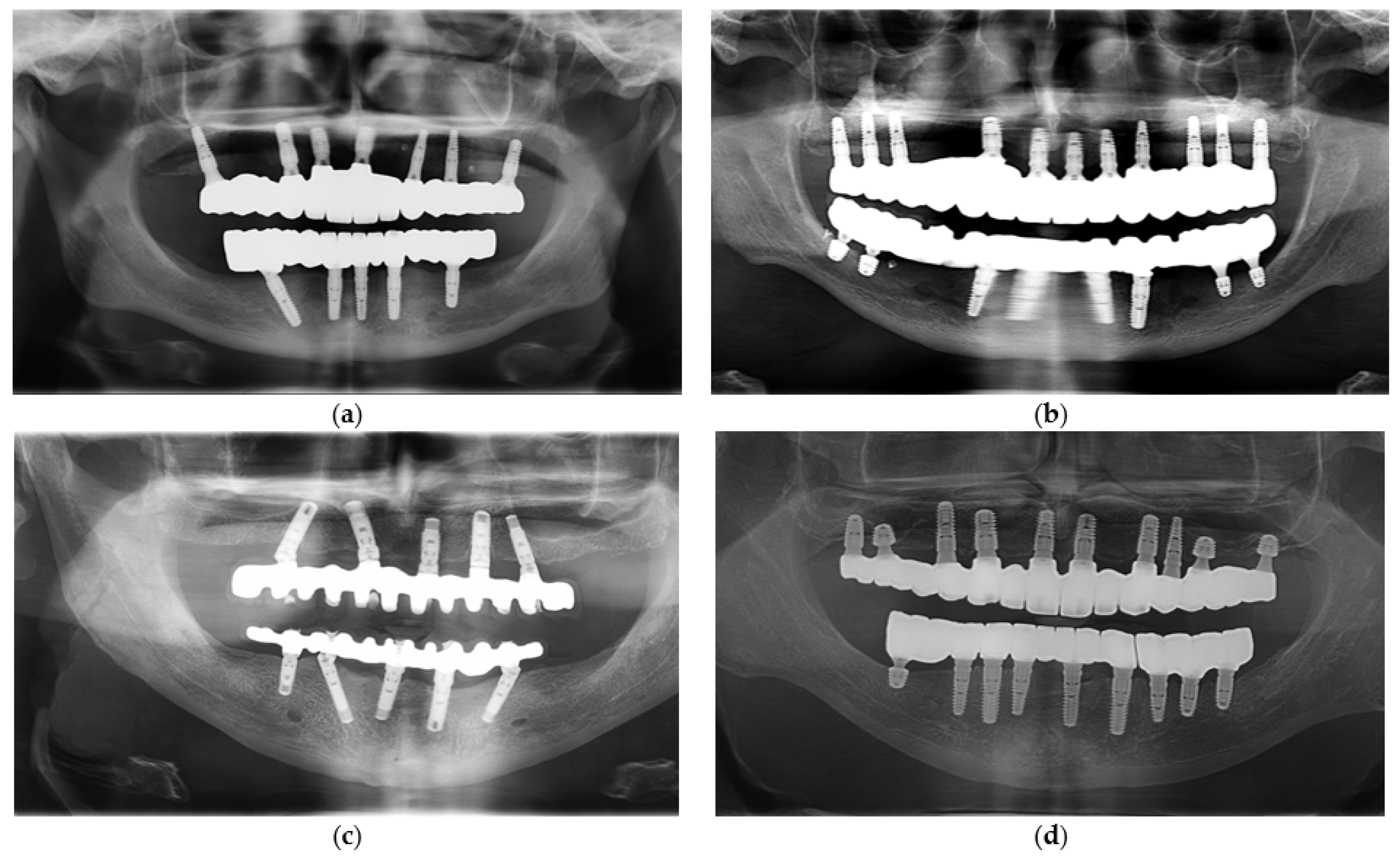

- Monolithic zirconia group (n = 10): restorations fabricated from high-strength monolithic zirconia frameworks without veneering ceramic.

- Hybrid metal-ceramic group (n = 10): restorations fabricated from cobalt-chromium (Co-Cr) frameworks veneered with feldspathic ceramic.

- Rehabilitation with a definitive fixed full-arch or partial-arch implant-supported restoration.

- Minimum of three years in continuous function since delivery.

- Stable peri-implant conditions at baseline and follow-up (no signs of mobility or active infection).

- Availability of complete clinical documentation, including photographs, radiographs, maintenance records, and patient-reported outcome forms.

- History or clinical evidence of bruxism or other parafunctional habits.

- Previous uncontrolled periodontal disease or untreated peri-implantitis.

- Systemic conditions affecting bone metabolism (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes, osteoporosis with bisphosphonate therapy).

- Incomplete or missing follow-up records.

- Heavy smoking (≥10 cigarettes/day), due to its known negative impact on implant healing and peri-implant tissue stability, which could confound the evaluation of prosthetic outcomes. Patients with stable implants who were light or former smokers were not excluded.

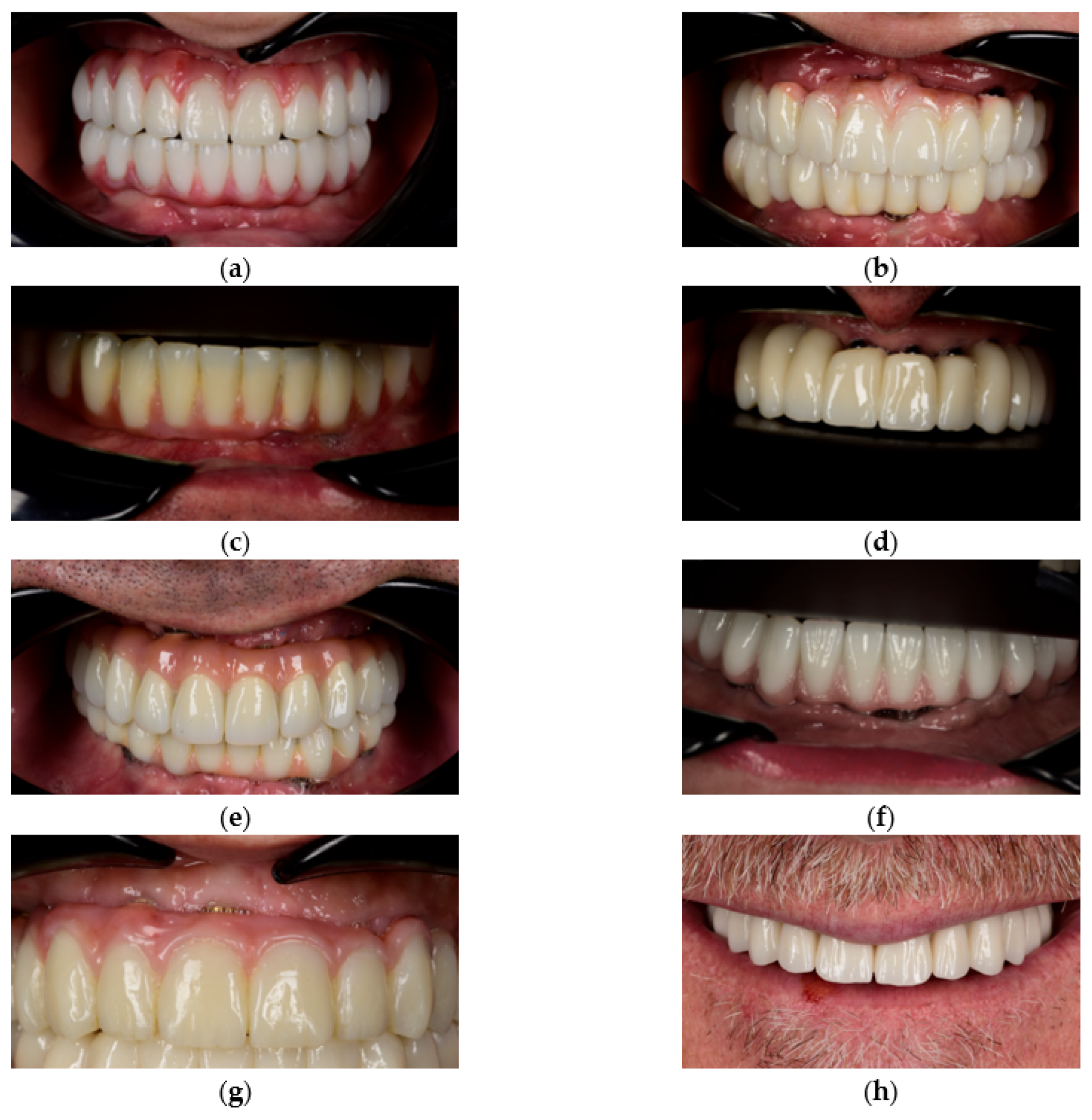

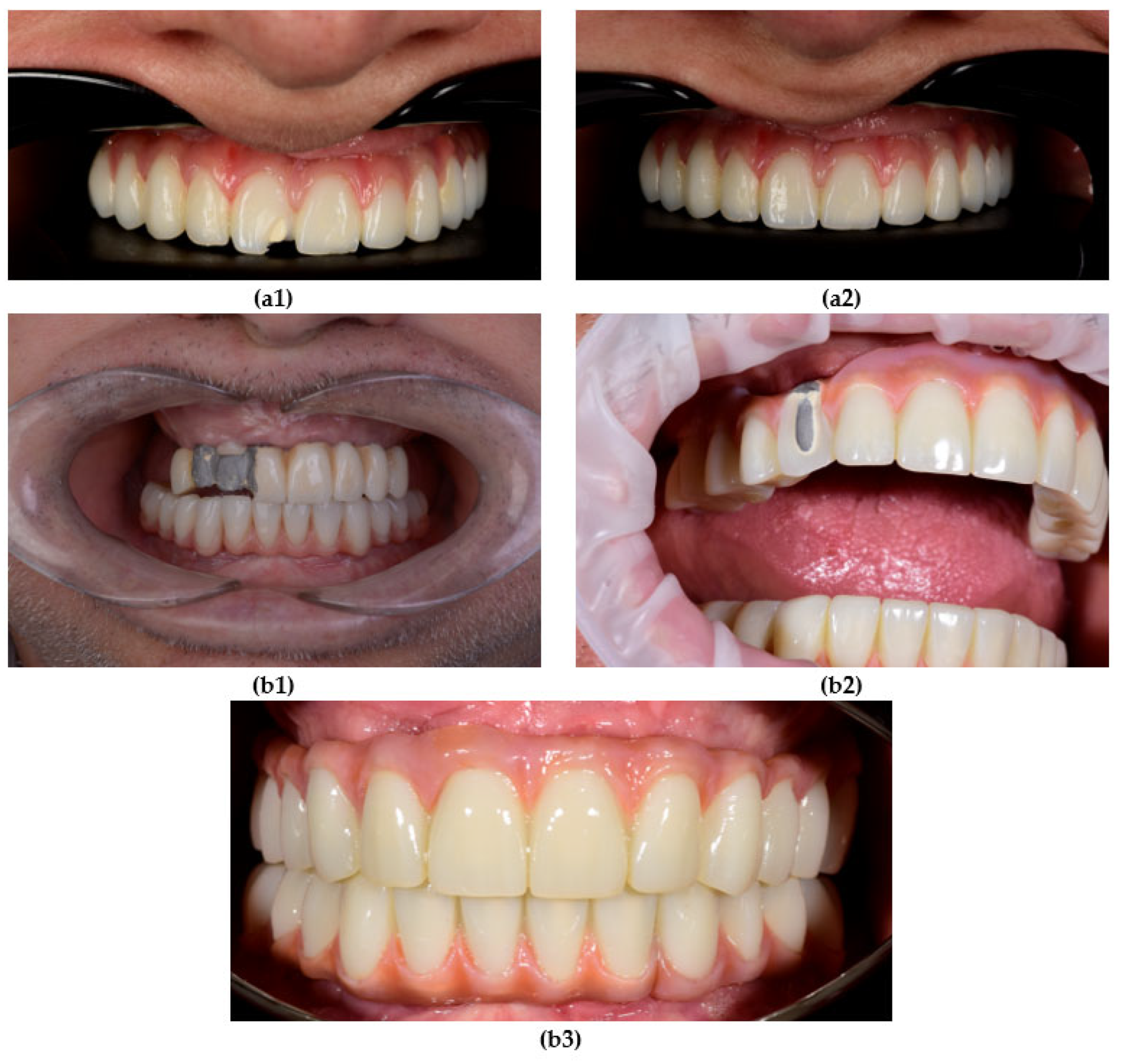

2.3. Prosthesis Fabrication Protocols

2.4. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

- Prosthetic framework complications—occurrence of framework fractures, deformation, or loss of integrity over time.

- Veneering ceramic complications—for hybrid metal–ceramic restorations, occurrence of chipping, delamination, or fracture of the veneering layer.

- Prosthetic gingiva adaptation—presence of soft tissue mismatch or loss of adaptation between the prosthetic gingiva and peri-implant soft tissues, documented through standardized frontal and lateral photographs.

- Mechanical retention issues—frequency of screw loosening or complete unscrewing events during the follow-up period.

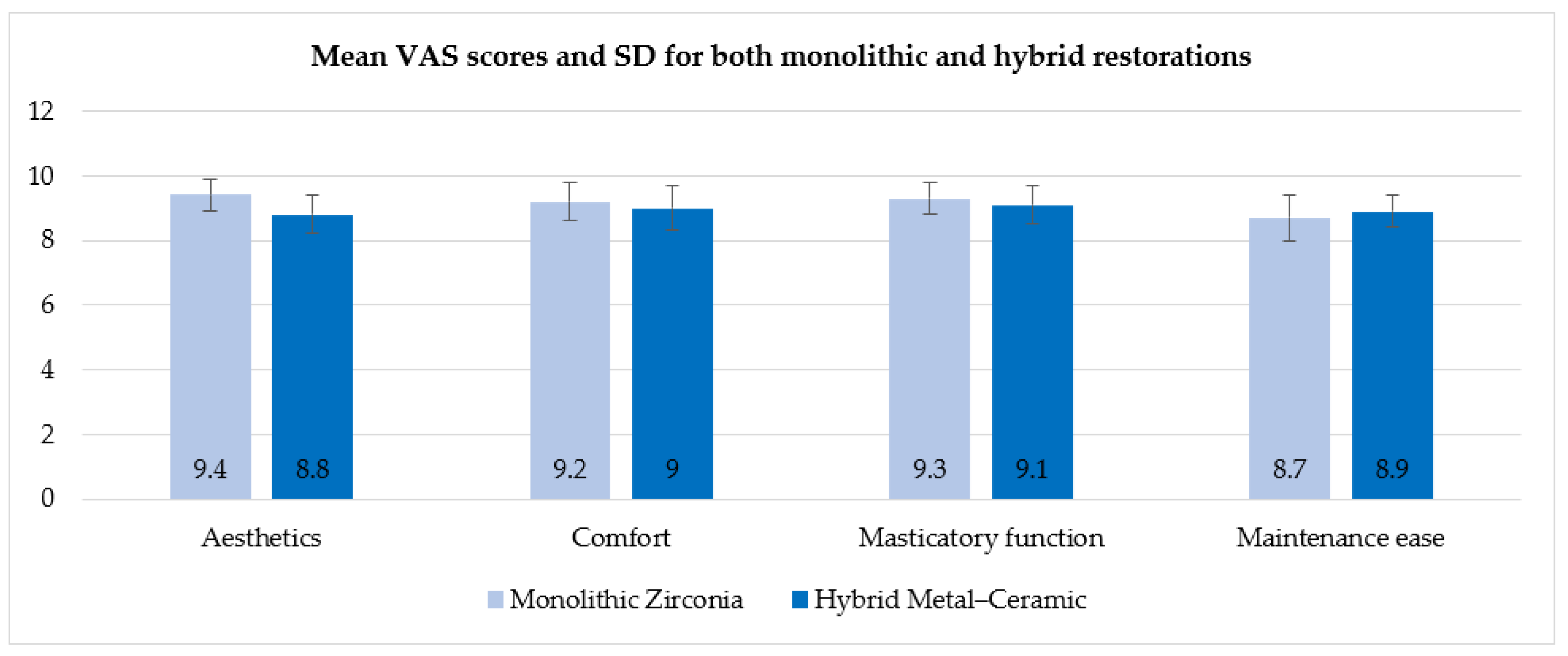

- Patient-reported esthetic and functional satisfaction—patient satisfaction was assessed using a four-item visual analog scale (VAS) covering esthetics, comfort, masticatory functions and maintenance ease. Each item was scored from 0 (“not satisfied at all”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

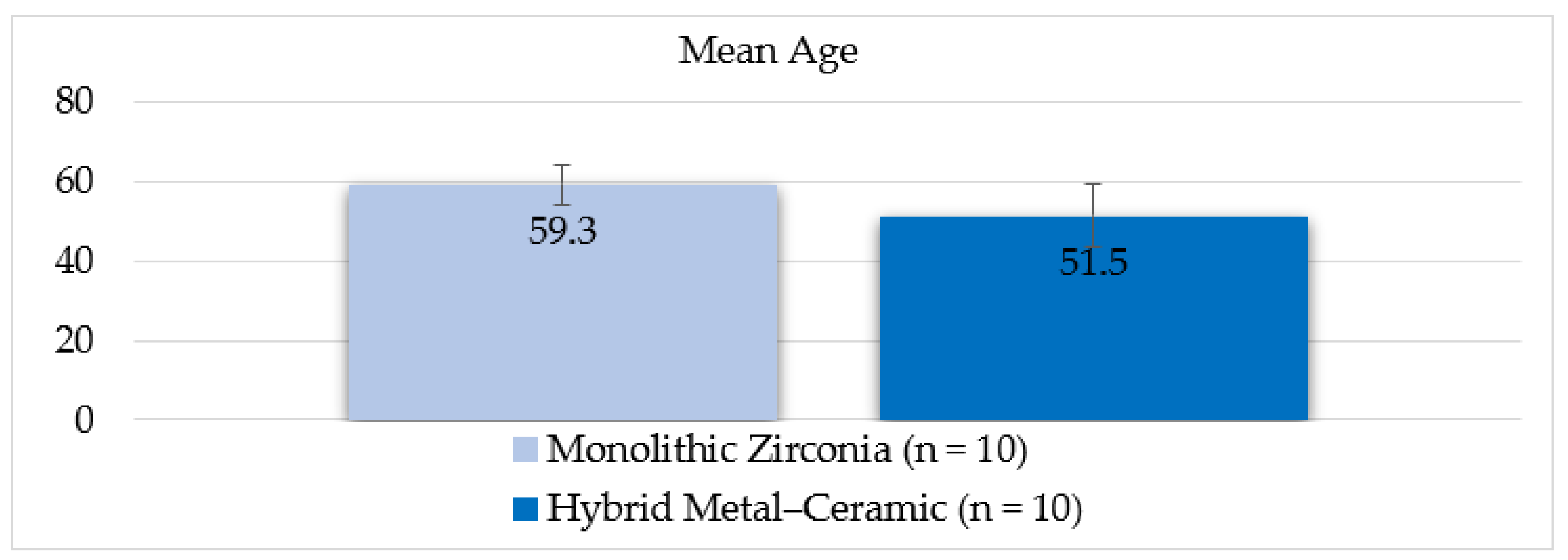

3.1. Sample Characteristics

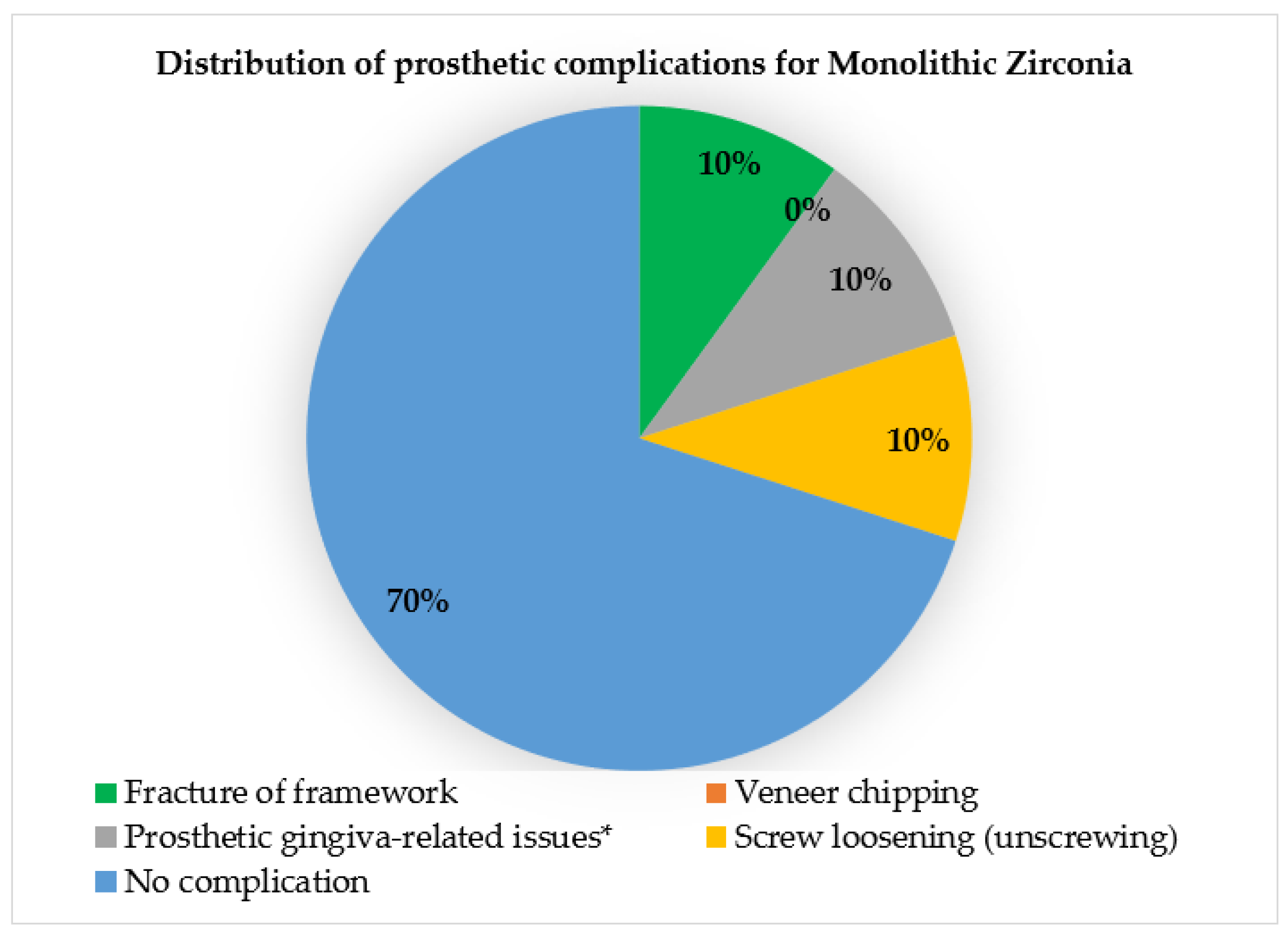

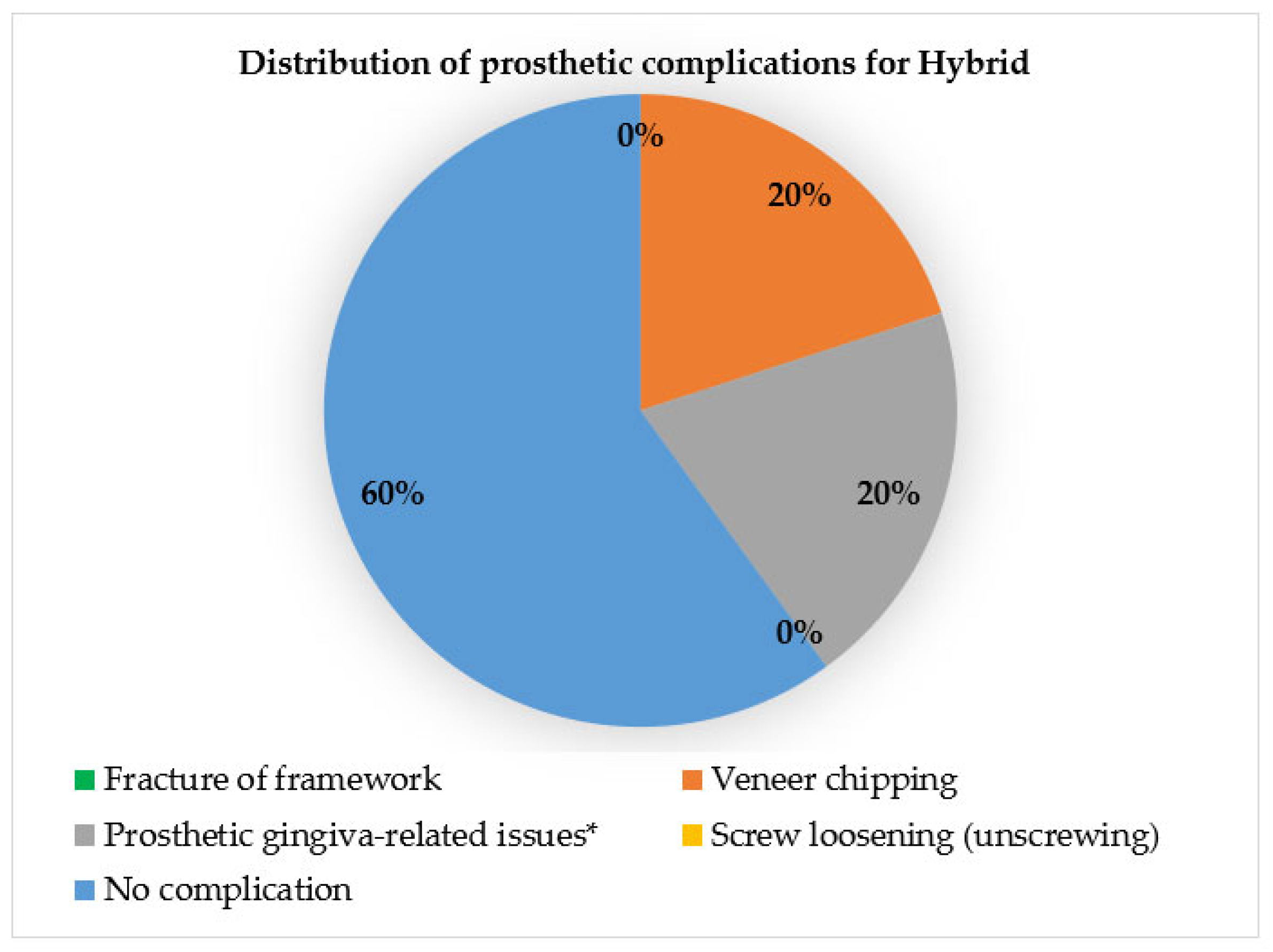

3.2. Complication Rates and Material-Related Outcomes

3.3. Patient-Reported Outcomes (VAS Questionnaire)

3.4. Wear and Surface Changes

3.5. Maintenance Procedures and Follow-Up

3.6. Key Findings and Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results and Comparison with Literature

4.2. Material Properties and Surface Management

4.3. Maintenance and Functional Considerations

4.4. Statistical and Methodological Limitations

4.5. Contribution to Current Evidence and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Co-Cr | Cobalt–Chromium |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TMJ | Temporomandibular Joint |

References

- Delucchi, F.; De Giovanni, E.; Pesce, P.; Bagnasco, F.; Pera, F.; Baldi, D.; Menini, M. Framework materials for full-arch implant-supported rehabilitations: A systematic review of clinical studies. Materials 2021, 14, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieralli, S.; Kohal, R.-J.; Rabel, K.; von Stein-Lausnitz, M.; Vach, K.; Spies, B.C. Clinical outcomes of partial and full-arch all-ceramic implant-supported fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jivraj, S.; Chee, W. Material considerations for full-arch implant-supported restorations. In Treatment Planning in Implant Dentistry; Chee, W., Jivraj, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanauskaite, A.; Becker, K.; Wolfart, S.; Lukman, F.; Schwarz, F. Efficacy of rehabilitation with different approaches of implant-supported full-arch prosthetic designs: A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, G.M.; Maiorana, C.; Gallo, M.; Codari, M.; Sforza, C. Implant-supported immediately loaded full-arch rehabilitations: Comparison of resin and zirconia clinical outcomes in a 5-year retrospective follow-up study. Implant. Dent. 2016, 25, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfante, E.A.; Suzuki, M.; Lorenzoni, F.C.; Sena, L.A.; Hirata, R.; Bonfante, G.; Coelho, P.G. Probability of survival of implant-supported metal ceramic and CAD/CAM resin nanoceramic crowns. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussi, C.A.; Ezatpour, H.R.; Haddadnia, J.; Gholami Shiri, J. Effect of using different metal and ceramic materials as restorations on stress distribution around dental implants: A comparative finite element study. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 115403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozzo, L.M.; Azevedo, L.; Fernandes, J.C.H.; Fonseca, P.; Araújo, F.; Teixeira, W.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Correia, A. The success and complications of complete-arch implant-supported fixed monolithic zirconia restorations: A systematic review. Prosthesis 2023, 5, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Li, X.C.; Bidra, A.S. Clinical outcomes of implant-supported monolithic zirconia crowns and fixed partial dentures: A systematic review. J. Prosthodont. 2022, 31, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkondu, Ö.; Tinastepe, N.; Akan, E.; Kazazoğlu, E. An overview of monolithic zirconia in dentistry. Balk. J. Dent. Med. 2016, 20, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Advantages and disadvantages of three common materials in dental use. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2798, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, C.A.A.; Verri, F.R.; de Luna Gomes, J.M.; de Souza Batista, V.E.; Silva Cruz, R.; Fernandes e Oliveira, H.F.F.; Pellizzer, E.P. Ceramic versus metal-ceramic implant-supported prostheses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grech, J.; Antunes, E. Zirconia in dental prosthetics: A literature review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 4956–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.K.; Narvekar, U.; Petridis, H. Prosthodontic complications of metal-ceramic and all-ceramic complete-arch fixed implant prostheses with minimum 5 years mean follow-up period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 27, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Bordin, T.B.; Natto, Z.S.; El-Rafie, K.; Pagni, S.E.; Chochlidakis, K.; Ercoli, C.; Weber, H.-P. Complications and survival rates of 55 metal-ceramic implant-supported fixed complete-arch prostheses: A cohort study with mean 5-year follow-up. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 123, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, I.; de Llanos-Lanchares, H.; Brizuela-Velasco, A.; Alvarez-Riesgo, J.-A.; Llorente-Pendas, S.; Herrero-Climent, M.; Alvarez-Arenal, A. Complications of fixed full-arch implant-supported metal-ceramic prostheses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-W.; Chien, C.-H.; Chen, C.-J.; Papaspyridakos, P. Complete-mouth implant rehabilitation with modified monolithic zirconia implant-supported fixed dental prostheses and an immediate-loading protocol: A clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 109, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmajeed, A.A.; Lim, K.G.; Närhi, T.O.; Cooper, L.F. Complete-arch implant-supported monolithic zirconia fixed dental prostheses: A systematic review. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 115, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezia, P.; Torsello, F.; Cavalcanti, R.; D’Amato, S. Retrospective analysis of 26 complete-arch implant-supported monolithic zirconia prostheses with feldspathic porcelain veneering limited to the facial surface. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischler, M.; Patch, C.; Bidra, A.S. Rehabilitation of edentulous jaws with zirconia complete-arch fixed implant-supported prostheses: An up to 4-year retrospective clinical study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 120, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanski, M.; Zmyslowska-Polakowska, E.; Osica, K.; Krasowski, M.; Sauro, S.; Hardan, L.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Mechanical properties of modern restorative “bioactive” dental materials—An in vitro study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, P.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; Ha, S.-R.; Seo, D.-G.; Ahn, J.-S.; Choi, Y.-S. Changes in the properties of different zones in multilayered translucent zirconia used in monolithic restorations during aging process. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailova, M.; Elsayed, A.; Fabel, G.; Edelhoff, D.; Zylla, I.-M.; Stawarczyk, B. Comparison between novel strength-gradient and color-gradient multilayered zirconia using conventional and high-speed sintering. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 110, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Rangel, J.; Nobre, M.d.A.; Ferro, A.; Nunes, M.; Almeida, R.; Guedes, C.M. A new full digital workflow for fixed prosthetic rehabilitation of full-arch edentulism using the All-on-4 concept. Medicina 2024, 60, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Kang, K.; DeFuria, C.; Amin, S.; Kudara, Y.; Weber, H.-P. Digital workflow in full-arch implant rehabilitation with segmented minimally veneered monolithic zirconia fixed dental prostheses: 2-year clinical follow-up. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 29, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borșanu, I.A.; Erdelyi, R.A.; Rusu, L.; Antonie, S.M.; Bratu, E.A. Full-arch implant-supported restorations: Hybrid versus monolithic design. In Advances in Dentures—Prosthetic Solutions, Materials and Technologies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidra, A.S.; Agar, J.R.; Taylor, T.D. Computer-aided technology for fabricating complete dentures: Systematic review of historical background, current status, and future perspectives. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 109, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lawn, B.R. Fatigue sensitivity of Y-TZP to microscale damage: A critical review. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, G.; Camurri Piloni, A.; Nicolin, V.; Turco, G.; Di Lenarda, R. Chairside CAD/CAM materials: Current trends of clinical uses. Biology 2021, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, I.; Fehér, A.; Filser, F.; Gauckler, L.J.; Lüthy, H.; Hämmerle, C.H.F. Prospective clinical study of zirconia posterior fixed partial dentures: 3-year follow-up. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2006, 19, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Kim, J.W. Graded structures for damage-resistant and aesthetic all-ceramic restorations. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haj Husain, N.; Özcan, M.; Molinero-Mourelle, P.; Joda, T. Clinical performance of partial and full-coverage fixed dental restorations fabricated from hybrid polymer and ceramic CAD/CAM materials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoveizi, R.; Baghaei, M.; Tavakolizadeh, S.; Tabatabaian, F. Color match of ultra-translucency multilayer zirconia restorations with different designs and backgrounds. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, P.F.; de Paula Miranda, R.B.; Santos, K.F.; Scherrer, S.S.; Zhang, Y. Recent advances in dental zirconia: 15 years of material and processing evolution. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Sailer, I.; Makarov, N.A.; Zwahlen, M.; Thoma, D.S. All-ceramic or metal-ceramic tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs)? A systematic review of the survival and complication rates. Part II: Multiple-unit FDPs. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 624–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, M.; Yang, B.; Ludwig, K.; Kern, M. Two-body wear of resin and ceramic denture teeth in comparison to human enamel. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickel, R.; Brüshaver, K.; Ilie, N. Repair of restorations—Criteria for decision making and clinical recommendations. Dent. Mater. 2013, 29, 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Stampa, C.; Schweyen, R.; Hey, J.; Boeckler, A. Retentive characteristics of a new attachment system for hybrid dentures. Materials 2020, 13, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, I.; Balmer, M.; Hüsler, J.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Känel, S.; Thoma, D.S. Ten-year randomized trial (RCT) of zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic fixed dental prostheses. J. Dent. 2018, 74, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Thoma, D.; Jung, R.; Zwahlen, M.; Zembic, A. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of implant-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) after a mean observation period of at least 5 years. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, K.N.; Nigro, R.P.; Costa, R.C.; Macedo, B.O.; Favero, S.S.; Miranda, R.B.P.; Bonfante, E.A.; Cesar, P.F. Effect of occlusal adjustment and subsequent repolishing on the surface roughness and volumetric wear of different types of glazed monolithic zirconia after chewing simulation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 151, 106809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Monolithic Zirconia (n = 10) | Hybrid Metal-Ceramic (n = 10) | Total (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 59.3 ± 4.9 | 51.5 ± 7.9 | 55.4 ± 7.5 |

| Sex, n (%): | |||

| Male | 6 (60.0) | 5 (50.0) | 11 (55.0) |

| Female | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Treated Arch, n (%): | |||

| Maxilla | 5 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 11 (55.0) |

| Mandible | 5 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 9 (45.0) |

| Follow-up (years), mean ± SD | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 1.5 |

| Age range (years) | 49–70 | 38–67 | 38–70 |

| Complication Type | Monolithic Zirconia (n = 10) | Hybrid Metal-Ceramic (n = 10) | Total (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture of framework | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| Veneer chipping | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (10.0%) |

| Prosthetic gingiva-related issues * | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 3 (15.0%) |

| Screw loosening (unscrewing) | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.0%) |

| No complication | 7 (70.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 13 (65.0%) |

| Domain | Monolithic Zirconia (n = 10) | Hybrid Metal-Ceramic (n = 10) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esthetics | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 0.03 |

| Comfort | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 0.42 |

| Masticatory function | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 0.38 |

| Maintenance ease | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.51 |

| Variable/Outcome | Monolithic Zirconia (n = 10) | Hybrid Metal-Ceramic (n = 10) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.3 ± 4.9 | 51.5 ± 7.9 | 0.06 | No significant difference |

| Sex (Male) | 60.0% | 50.0% | 0.68 | No significant difference |

| Treated Arch (Maxilla) | 50.0% | 60.0% | 0.71 | No significant difference |

| Follow-up (years) | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 3.0 ± 1.5 | 1.00 | Identical follow-up |

| Framework fracture | 10.0% | 0.0% | 0.30 | Not significant |

| Veneer chipping | 0.0% | 20.0% | 0.14 | Not significant |

| Prosthetic gingiva-related issues | 10.0% | 20.0% | 0.53 | Not significant |

| Screw loosening | 10.0% | 0.0% | 0.30 | Not significant |

| VAS-Esthetics | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 0.03 | Significant, higher in monolithic |

| VAS-Comfort | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.7 | 0.42 | No significant difference |

| VAS-Masticatory function | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 0.38 | No significant difference |

| VAS-Maintenance ease | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 0.51 | No significant difference |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antonie, S.-M.; Rusu, L.-C.; Borsanu, I.-A.; Bratu, E.-A. Preliminary Comparative Analysis of Monolithic Zirconia and Hybrid Metal–Ceramic Designs in Full-Arch Implant-Supported Restorations. Prosthesis 2025, 7, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060154

Antonie S-M, Rusu L-C, Borsanu I-A, Bratu E-A. Preliminary Comparative Analysis of Monolithic Zirconia and Hybrid Metal–Ceramic Designs in Full-Arch Implant-Supported Restorations. Prosthesis. 2025; 7(6):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060154

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntonie, Sergiu-Manuel, Laura-Cristina Rusu, Ioan-Achim Borsanu, and Emanuel-Adrian Bratu. 2025. "Preliminary Comparative Analysis of Monolithic Zirconia and Hybrid Metal–Ceramic Designs in Full-Arch Implant-Supported Restorations" Prosthesis 7, no. 6: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060154

APA StyleAntonie, S.-M., Rusu, L.-C., Borsanu, I.-A., & Bratu, E.-A. (2025). Preliminary Comparative Analysis of Monolithic Zirconia and Hybrid Metal–Ceramic Designs in Full-Arch Implant-Supported Restorations. Prosthesis, 7(6), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis7060154