1. Introduction

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are increasingly used in surveillance, reconnaissance, search and rescue, and spectrum monitoring missions. Their ability to operate in remote, inaccessible, or dangerous areas makes them ideal platforms for radio frequency (RF) sensing tasks, including Direction-of-Arrival (DoA) estimation. Accurate DoA estimation enables UAVs to locate ground-based emitters, support jamming avoidance, enhance navigation in GPS-denied environments, and assist in electronic warfare and disaster response scenarios [

1]. DoA estimation is a key component of RF-based localization because it provides the angular bearings necessary to track drones. It relies on measuring the phase or amplitude differences of a signal received by multiple spatially separated antennas. Classic subspace-based algorithms such as multiple signal classification (MUSIC) operate on the covariance matrix of the array output and exploit the orthogonality between signal and noise subspaces. For uniform linear arrays (ULAs), MUSIC can localize multiple emitters in azimuth, but it suffers from front–back ambiguity and end-fire errors. It also cannot distinguish elevation [

2]. Uniform Circular Arrays (UCAs) mitigate these issues by offering 360° azimuth coverage and the ability to estimate elevation, albeit at the cost of more complex calibration and processing.

1.1. Motivation

Phased array antennas offer the capability to steer beams electronically without moving parts, which is particularly advantageous for UAV applications where size, weight, and power (SWaP) are constrained. By applying controlled phase shifts to the individual elements, these arrays can enhance gain in a desired direction and suppress interference, allowing for real-time tracking of RF sources. Previous works have demonstrated phased array systems for DoA estimation in terrestrial and maritime environments [

3,

4], and some recent studies have explored their integration on aircraft and satellites [

5,

6]. At the same time, broader research within the UAV and wireless communication community has addressed interference mitigation, adaptive swarm mission planning, UAV positioning using 5G New Radio, and digital-twin-empowered optimization for UAV networks [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], all of which highlight the increasing demand for resilient and intelligent UAV sensing architectures.

Accurate DoA estimation also depends on array geometry, inter-element spacing and platform effects. When antennas are mounted on UAVs, electromagnetic interactions with the airframe can distort the radiation pattern, potentially degrading estimation accuracy. Current research explores several hardware architectures to address these challenges [

13]. For example, a low-cost switched-beam system uses six circularly arranged directional antennas connected to a single receiver through RF switches to estimate the angle of arrival of drone video signals [

14]. It achieved a mean error below

while eliminating multi-receiver synchronization. Distributed phased-array concepts for UAV swarms are also being explored. A recent prototype uses magnetic, hands-free RF connectors to dock multiple UAVs mid-flight, maintaining precise inter-element spacing and phase coherence while steering beams toward multiple directions [

15,

16]. These developments complement earlier work in communication system analysis and optimization for future aviation and wireless networks [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Recent work has strengthened ISAC foundations specifically for UAVplatforms. On the network side, Bithas et al. analyze aerial ISAC networks and quantify the sensing–communication trade-off (coverage probability vs. detection probability) under shadowing and interference, including a UAV selection policy that improves performance [

21]. At the channel level, Li et al. propose a UAV ISAC channel model with joint/shared clusters and birth–death (B–D) evolution to capture altitude-dependent angular/delay statistics, offering a physics-grounded basis for UAV ISAC link design [

22]. For algorithmic coupling between radar and comms, Ding et al. present a fully distributed joint radar–communication optimization for distributed airborne radar that explicitly enforces communication constraints while maximizing AOA-based localization performance [

23]. At the waveform level, Li et al. design complementary-sequence JRC waveforms (and a Doppler-resilient variant) that reduce range sidelobes without degrading BER, directly relevant to ISAC tracking on moving aerial platforms [

24]. From a hardware and phased-array integration perspective, Sen et al. review RF front-ends, antenna/beamformer options, and self-interference cancellation for JCRS, highlighting practical constraints for compact arrays and co-designed transceivers [

25]. These studies complement our focus on UAV-mounted UCA manifolds, platform coupling, and pose/Doppler-aware MUSIC, and they motivate our hybrid WAA–CTF estimator and platform-aware validation.

1.2. Research Gap and Contributions

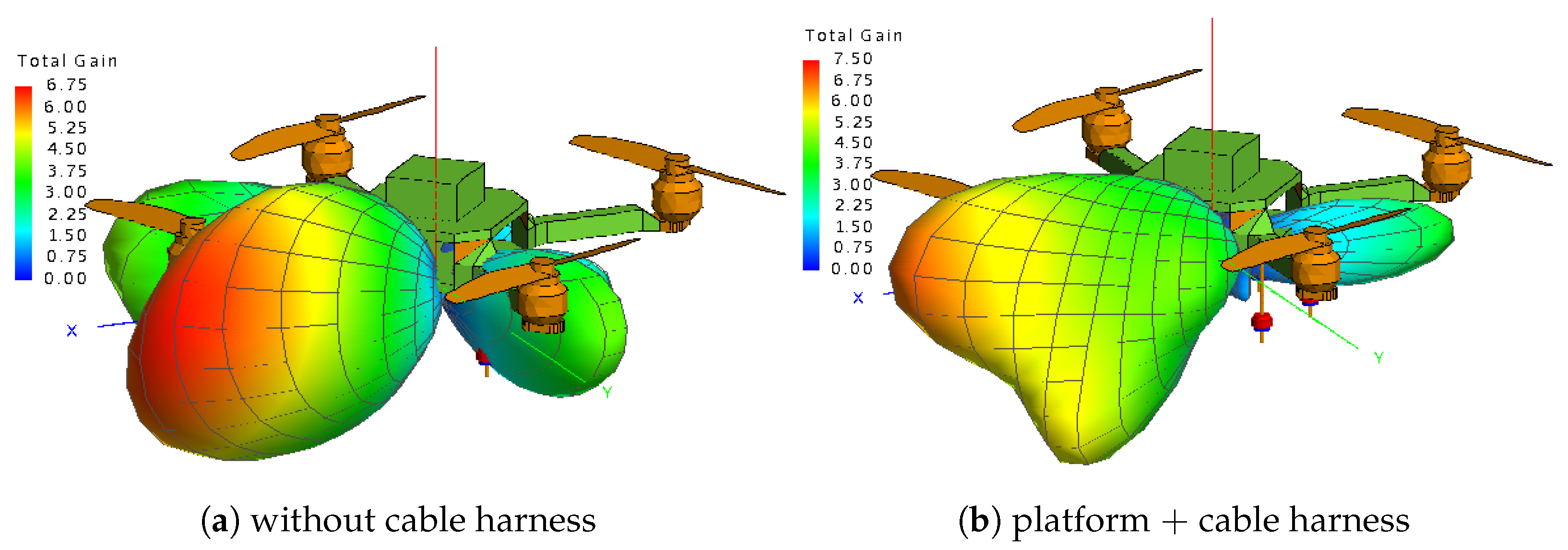

A major challenge in implementing phased arrays on UAVs lies in accounting for electromagnetic interactions between the antenna array and the drone body. The proximity of motors, arms, and batteries can distort the radiation pattern, reduce gain, and introduce multipath effects. These platform-specific influences are often overlooked in simplified array models, and limited work has been carried out on simulating compact phased arrays mounted on UAVs, especially under non-planar surfaces and platform-induced distortions. This paper presents a simulation-based study of a drone-mounted phased array using Altair FEKO. A compact circular array is designed and evaluated for its Direction-of-Arrival (DoA) estimation capability across a range of steering angles and incidence scenarios. Unlike prior work that assumes ideal free-space conditions, this study incorporates the full 3D electromagnetic model of a quadcopter to capture realistic loading, shadowing, and scattering effects. The results provide new insights into angular resolution, main lobe accuracy, and side lobe performance for airborne RF sensing.

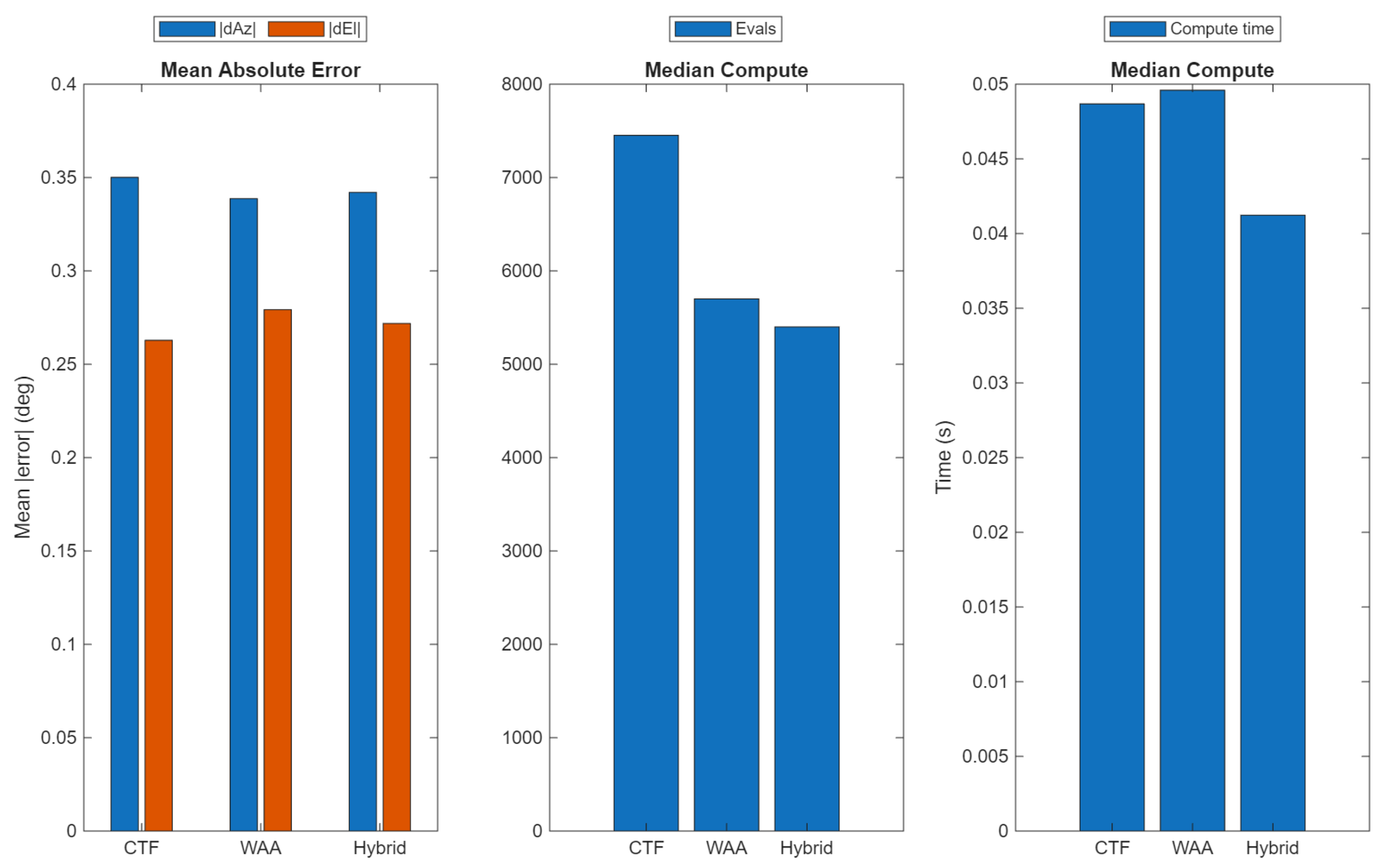

Furthermore, a Pose-Aware, Doppler-Aware MUSIC algorithmis developed to address UAV dynamics. Standard MUSIC assumes a fixed array; however, UAVs experience pose variations (yaw, pitch, roll) and Doppler shifts due to motion. The proposed algorithm compensates for both effects by modifying the array manifold and covariance modeling. To enhance efficiency, a hybrid Coarse-to-Fine (CTF) and Weighted Average Algorithm (WAA) framework is introduced, where the CTF stage identifies coarse candidate regions and the WAA stage refines estimates via intelligent spectrum search. This reduces computational complexity by orders of magnitude compared with exhaustive searches while retaining high resolution.

The contributions of this paper are

Development of a phased array antenna model for UAV integration and simulation of platform effects.

Introduction of a novel Pose-Aware, Doppler-Aware MUSIC algorithm with hybrid CTF–WAA optimization for robust, real-time DoA estimation.

Quantitative analysis of UAV-based DoA performance for low-altitude, passive RF localization tasks.

This study supports the demand for lightweight and accurate RF sensing on UAVs and provides a foundation for experimental validation and system-level deployment.

2. Phased Array Antenna Design

In UAV-based RF sensing systems, the design of a compact and lightweight phased array antenna is crucial for ensuring omnidirectional angular coverage, robust beam steering, and integration within the platform’s size, weight, and power (SWaP) constraints. This section presents the design methodology of a Uniform Circular Array (UCA), including element selection, frequency choice, array geometry, and beam steering principles tailored to UAV integration.

A half-wavelength dipole was selected as the fundamental antenna element owing to its omnidirectional radiation in the azimuth plane, simple structure, and ease of simulation. The operating frequency is set to 2.4 GHz, corresponding to the industrial, scientific, and medical (ISM) band commonly used for UAV command and control, telemetry, and real-time video transmission. This frequency ensures moderate propagation range, low atmospheric loss, and manageable element size, making it suitable for both simulation and physical implementation.

To achieve

azimuthal coverage and reduce direction-dependent performance variations, a Uniform Circular Array (UCA) configuration was chosen over a Uniform Linear Array (ULA). Unlike ULAs, which suffer from reduced performance at endfire angles, UCAs offer rotational symmetry, making them inherently robust to changes in UAV yaw or heading. This makes them well-suited for airborne platforms operating in dynamic environments [

26]. The detailed rationale behind each array parameter is summarized in

Table 1. In addition, similar UCA settings are used in recent Direction Finding (DF) systems (e.g., a six-element UCA operating at 2.4 GHz with approximately half-wavelength inter-element spacing), contributing to the progress of similar existing work [

1].

Table 1 provides a concise justification of the chosen configuration. The six-element, 2.4 GHz UCA with radius

offers an optimal balance between spatial resolution, coupling control, and ease of airframe integration. A half-wavelength dipole was selected as the array element due to its omnidirectional azimuthal radiation pattern, compact size, and ease of simulation in free space. Dipoles provide uniform angular sensitivity, which is ideal for 360° Direction-of-Arrival (DoA) estimation in Uniform Circular Arrays (UCAs). Unlike microstrip patches, dipoles do not require substrate modeling, simplifying design and reducing computational complexity. Their symmetric radiation and structural simplicity make them well-suited for circular arrangements on small UAV platforms, enabling effective beam steering analysis with minimal fabrication constraints.

From a simulation standpoint, dipoles can be efficiently modeled using thin-wire segments in Altair FEKO, allowing for rapid iteration and reduced meshing complexity. This facilitates focused evaluation of array behavior without the added overhead of substrate modeling, dielectric losses, or feed structure optimization typically associated with microstrip antennas. Moreover, dipoles are lightweight, structurally simple, and commonly used in UAV telemetry systems, making them viable for eventual physical integration.

2.1. Single Dipole Element Design

A half-wavelength dipole antenna was designed and simulated at 2.4 GHz using Altair FEKO to serve as the element for the Uniform Circular Array. The parameters used to design the dipole element is summarized in

Table 2 below.

The dipole consists of two wire segments, each 31.25 mm in length, and fed by a discrete voltage source at the center. Full-wave simulations were carried out to evaluate return loss and radiation characteristics in free space.

The simulated

curve (

Figure 1) shows a −10 dB impedance bandwidth spanning from 2.13 GHz to 2.53 GHz, with a minimum reflection coefficient of −14.7 dB near 2.33 GHz. This indicates good impedance matching across the desired ISM band. The corresponding 3D radiation pattern (

Figure 2) exhibits the expected doughnut-shaped profile, characteristic of a dipole in free space, with peak gain oriented in the azimuthal plane and deep nulls along the vertical (z-axis). The maximum gain is approximately 1.7 dBi, providing an omnidirectional response suitable for circular array deployment.

2.2. UCA Construction and Steering Setup

2.2.1. UCA Geometry Construction

A six-element Uniform Circular Array (UCA) was designed in Altair FEKO (CADFEKO) using half-wave dipole antennas tuned to resonate at 2.4 GHz. Each dipole was modeled with a wire of an overall length of approximately and a radius of 0.5 mm, fed by a delta-gap voltage source at the center split.

The dipole elements were positioned uniformly on a circular ring of radius R. For the present configuration, a normalized radius of

was selected to ensure arc spacing close to

, thereby minimizing mutual coupling while avoiding grating lobes during azimuthal beam steering. The element azimuths are given by

where

N is the number of elements (here,

N = 6), and

denotes the angular reference of the first element relative to the array axis. The constructed UCA and the corresponding radiation pattern without any individual excitation are shown in

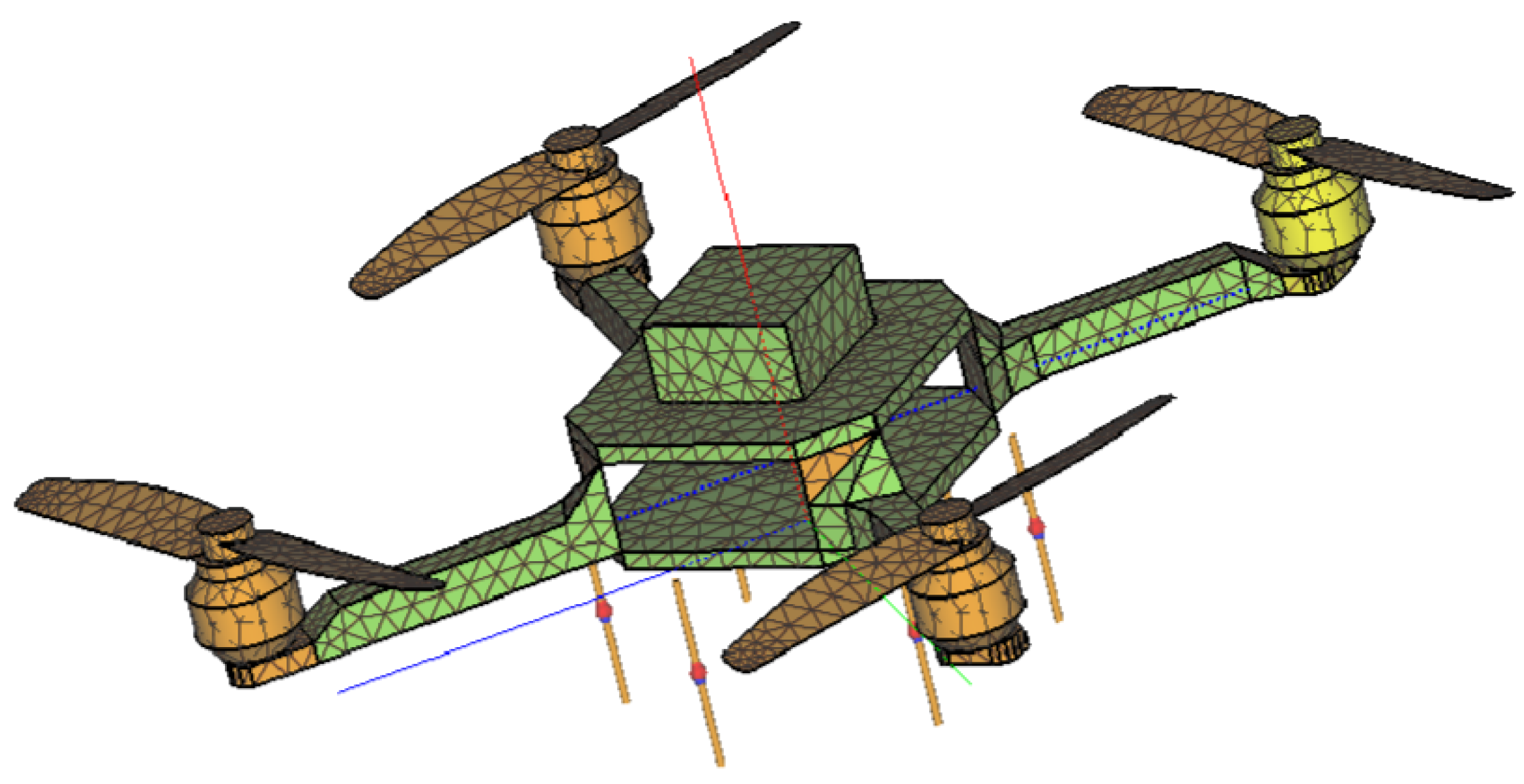

Figure 3. The array geometry is defined in the UAV body–frame coordinates and later rigidly attached to the quadcopter model (

Section 3), so the same analytically specified element positions and geometry are used in both free-space and platform-integrated simulations.

2.2.2. Beam Steering Setup in FEKO

Each dipole element was excited with a voltage source of equal magnitude (1 V), and progressive phase shifts were applied to the sources according to the steering law. CADFEKO’s scripting interface (Lua API) was used to automate the calculation and assignment of excitation phases.

- 1.

Phase steering law

The required excitation phase for element n to form a beam in the desired direction

is derived from the UCA array factor:

where

is the wave number;

R is the array radius;

and are steering elevation and azimuth angles;

is the angular position of the element n.

Converting to degrees (as required in FEKO)

for azimuthal steering (

), this reduces to

- 2.

Excitation assignment

In CADFEKO, a single solution configuration (StandardConfiguration1) was defined. The Lua script iterates over all sources (VoltageSource1...VoltageSourceN) and assigns the computed values to the Phase property of each source. Magnitudes remain unity unless amplitude tapering is introduced (e.g., Taylor distribution for sidelobe suppression).

- 3.

Pseudocode for UCA steering

The .luascript was structured to minimize user effort, with interactive forms for input and automatic generation of phase-steered models. The high-level pseudocode is shown in Algorithm 1.

The Lua script was implemented to automatically assign progressive phase excitations to the six dipole ports in the Uniform Circular Array (UCA). By varying the steering azimuth , new excitation sets were created without manual intervention. This enabled rapid generation of multiple steering cases, significantly reducing modeling time and potential errors.

The steering angles evaluated were

corresponding to six uniformly distributed beam directions in the azimuth plane.

The excitation phases obtained from the Lua script for six steering angles are summarized in

Table 3. Each voltage source corresponds to one dipole element of the UCA, with equal magnitude excitations of 1 V and phase shifts as listed. The table highlights the symmetry of the UCA: opposite elements are excited with approximately conjugate phases, and the patterns repeat with

periodicity. Small deviations from exact multiples of

or

(e.g.,

instead of

) arise from numerical precision in the steering law computation. These phase assignments ensure that the main beam is directed towards the desired azimuth angle

while maintaining the array’s circular symmetry.

| Algorithm 1 Lua Script for UCA Steering Setup |

- 1:

Get FEKO application instance - 2:

Define: - 3:

Frequency f (GHz) - 4:

Number of elements N - 5:

Array radius R (mm) - 6:

Steering angles (degrees) - 7:

Start angle of element #1 - 8:

Compute wavelength - 9:

Compute wavenumber - 10:

for to N do - 11:

- 12:

Compute excitation phase (degrees): - 13:

Wrap to range - 14:

Identify source name “VoltageSource” - 15:

Retrieve source properties - 16:

Set Phase = , Magnitude = 1 V - 17:

Update properties in configuration - 18:

end for - 19:

Save updated model as

|

2.3. Evaluation of Reflection Coefficient

The

plots at each

are shown in

Figure 4. In all cases, the

dB passband consistently spans

with variations of only a few megahertz across

. The corresponding fractional bandwidth is

The minimum of

occurs close to the design frequency of 2.4 GHz for every steering case, with a depth of approximately

dB. Importantly, at 2.4 GHz, the active reflection coefficient remains below

dB for all

, confirming adequate matching across the ISM band. The near-invariance of

,

, and the notch depth with steering demonstrates that the UCA maintains stable impedance characteristics under azimuthal scan, which is beneficial for downstream DoA processing.

2.4. Far Field Patterns for the UCA

Figure 5 shows the normalized 2D azimuth patterns (

) for six steering angles

. In each case, the main beam aligns with the commanded azimuth, confirming correct phase excitation. A complementary back lobe appears at

, as expected for a single-ring UCA.

The measured half-power beamwidths (HPBWs) from the FEKO plots are listed in

Table 4. The broader beams at

and

compared to the ∼

HPBW at the other scan angles are attributed to the interaction between the element pattern and the active array factor under scan.

In the cuts shown in

Figure 5, the sidelobe level (SLL) is reported in linear units and defined as the ratio between the maximum beam strength and the second-largest beam. The apparent variation between

and ≈

, and between the corresponding SLL values in

Table 4, is primarily a consequence of how the fixed

cut is taken for each steered beam in the global reference frame. Depending on the steering angle, this cut may intersect the main lobe together with its complementary back lobe, or only small local ripples, so the extracted HPBW/SLL values are cut-dependent rather than reflecting a true physical asymmetry between, for example,

and

. The underlying 3D UCA beams are rotationally symmetric, and hence the intrinsic angular resolution of the array is essentially uniform with azimuth. In the MUSIC results that follow, the full 3D manifold is used, so any mild scan-angle dependence of the local pseudospectrum shape is captured without implying a change in the fundamental array resolution.

2.5. Three-Dimensional Far-Field Radiation Patterns

Figure 6 presents the three-dimensional realized gain patterns of the six-element UCA at

GHz for steering angles

with

. In each case, the main lobe is directed towards the commanded azimuth, validating the excitation control.

The 3D plots confirm the observations made from the 2D azimuth cuts:

For and , the main beams are broad () with sidelobe levels around dB.

For , , , and , the beams are narrower () but exhibit higher sidelobe levels (≈0 dB relative to the main lobe).

A complementary back lobe appears at , as expected for a single-ring UCA.

The realized gain ranges from 6–7.5 dB in the main lobe direction, providing adequate directivity for DoA estimation. The 3D visualization also illustrates the tradeoff between beamwidth and sidelobe control at different steering angles.

6. Effect of Drone on DoA Estimation

Drone-mounted arrays do not behave like ideal free-space arrays. The airframe, wiring, and payload introduce mutual coupling between elements, small per-element gain/phase imbalances, and position jitter (mm-level placement errors). Flight adds multipath (modeled well by a Rician

K-factor) [

28], pose changes (yaw–pitch–roll), and Doppler from motion. Together, these effects distort the array’s steering vector, so the received data follow an effective manifold

rather than the ideal

. Here,

C models coupling (with magnitude/phase summarized by

),

G captures per-element complex gains, and

represents the placement errors. If the estimator still uses

, MUSIC peaks shift and broaden, producing bias floors and loss of resolution. This is visible in our results: mismatch heatmaps highlight angles where

is largest, and sweeps versus

K,

, and jitter quantify how bias grows as the platform departs from ideal conditions.

A practical remedy is to build and use a platform-aware manifold [

29,

30]. The existing Lua beam-steering script can automate this by sweeping programmed beams (TX reciprocity) or sequentially exciting elements under a probe/beacon to tabulate

for a few representative poses. At run time, IMU pose rotates candidate directions into the body frame; the estimator interpolates the measured manifold and then runs the Hybrid CTF→WAA search (coarse grid seeds followed by local refinement) on the MUSIC pseudospectrum. Using

suppresses platform-induced bias and recovers resolution in realistic flight, while the same heatmaps and effect sweeps guide calibration priorities (reduce

, tighten mechanics, or operate at higher

K) and provide concrete system requirements for the airframe and RF chain.

The platform impact is evaluated by generating a platform–aware array manifold on the full airframe model. For each look direction

and pose

R (yaw–pitch–roll), embedded-element responses are obtained and converted into steering vectors

(phase/gain referenced and unit–norm). Using the same data window and noise conditions as in the ideal study, two MUSIC pseudospectra are then formed for comparison with the previous section: (i) an ideal case, where both the covariance and the search manifold use the free-space model

, and (ii) a drone-loaded case, where the covariance reflects the FEKO-derived manifold (i.e., coupling, gain/phase imbalance, position jitter, and scattering), while the search still uses the ideal manifold

to expose mismatch. The resulting normalized pseudospectra are shown in

Figure 13.

Figure 13 visualizes the Hybrid PA-MUSIC pseudospectrum for case 01. The left panel (‘Ideal manifold’) forms the covariance with uncoupled, perfectly calibrated dipoles and free-space propagation, and searches with the corresponding ideal dictionary. The right panel (‘With drone effects’) forms the covariance with mutual coupling, per-element gain/phase imbalance, Doppler and pose effects, while the search manifold is still ideal. In both panels, the pseudospectrum is normalized by its global maximum and plotted in dB so that 0 dB corresponds to the strongest peak and the color bar indicates relative levels. The main lobe is therefore simply the global maximum, and the ground-truth DoA is marked by ‘×’. In the ideal case, the peak is sharp and centered on the truth, with a narrow mainlobe and a sidelobe floor roughly 20–25 dB below the maximum. On the heatmap, these sidelobes appear as the fainter vertical streaks next to the main bright ridge. When drone effects are included, the mainlobe broadens and its peak shifts by about 5–

in azimuth/elevation on average (and up to ≈13° in the worst of the ten cases in

Table 10). At the same time, the sidelobe floor rises to only about 10–12 dB below the peak, yielding a visibly flatter and less symmetric pseudospectrum. These changes illustrate how manifold mismatch from coupling, RF imbalance, jitter, and multipath introduces systematic bias and reduces sidelobe contrast when an ideal manifold is used in the search.

The changes arise because the received data follow an hleffective manifold rather than the ideal . Mutual coupling (C) and RF imbalances (G) reshape the array response; mm-level position jitter () adds direction-dependent phase errors; and low-K multipath injects coherent components that reduce signal/noise-subspace orthogonality, all of which flatten the pseudospectrum and displace the maximum. For DoA estimation, this means that, if the search uses an ideal manifold, one should expect systematic bias(peak shift), reduced resolution (broader mainlobe, higher sidelobes), and lower robustness to close sources. Using a platform-aware (measured or calibrated) manifold in the Hybrid CTF→WAA estimator restores peak sharpness and contrast, thereby suppressing bias floors and preserving resolution under realistic flight conditions.

The electromagnetic degradations in

Table 6 translate into DoA accuracy penalties when the search manifold ignores platform loading;

Table 11 summarizes this effect over ten cases. Compared with the ideal free-space case, the errors are larger (mean absolute

, RMSE

) because the received data are generated by a platform-loaded manifold (coupling, gain/phase imbalance, element jitter, multipath, and motion), whereas the MUSIC search continues to assume an ideal textbook manifold. This deliberate mismatch, used to isolate the penalty of ignoring platform effects and to represent a no-calibration baseline, shifts and broadens the pseudospectrum peak, yielding the observed

average error. In the experiments, the covariance is formed from drone-loaded data while the steering vectors remain ideal. Substituting a platform-aware (FEKO/OTA-measured) manifold, pose-rotated at run time, is expected to suppress bias and recover resolution.

Analysis of Platform Effects on Hybrid PA-MUSIC Using FEKO Manifolds

Platform effects were obtained from full-wave FEKO simulations of the complete airframe and antenna installation. For each look direction and representative pose (yaw–pitch–roll), FEKO provided embedded-element patterns and port-to-port S-parameters, from which a platform-aware steering dictionary and coupling matrix C were derived in MATLAB. The Rician K-factor was swept by adjusting the relative weighting of the FEKO direct (LOS) and scattered fields, while mechanical tolerances were emulated by re-solving the FEKO model with element coordinates. The Hybrid PA-MUSIC estimator (coarse CTF seeds followed by WAA refinement) was then evaluated by forming covariances consistent with the FEKO manifold and, for isolation of platform penalties, comparing against a search that still assumes an ideal free-space manifold. This setup exposes the mismatch that would arise if platform-aware calibration were omitted.

Mutual coupling is incorporated at the manifold level by premultiplying the ideal steering vector

with the coupling matrix

C, so that the effective manifold is consistent with

If we stack the effective steering vectors into

and denote the source covariance by

, then the array covariance takes the form

Thus, the impact of coupling, per-element gain/phase imbalance and position jitter is fully embedded in the signal and noise subspaces used by PA–MUSIC.

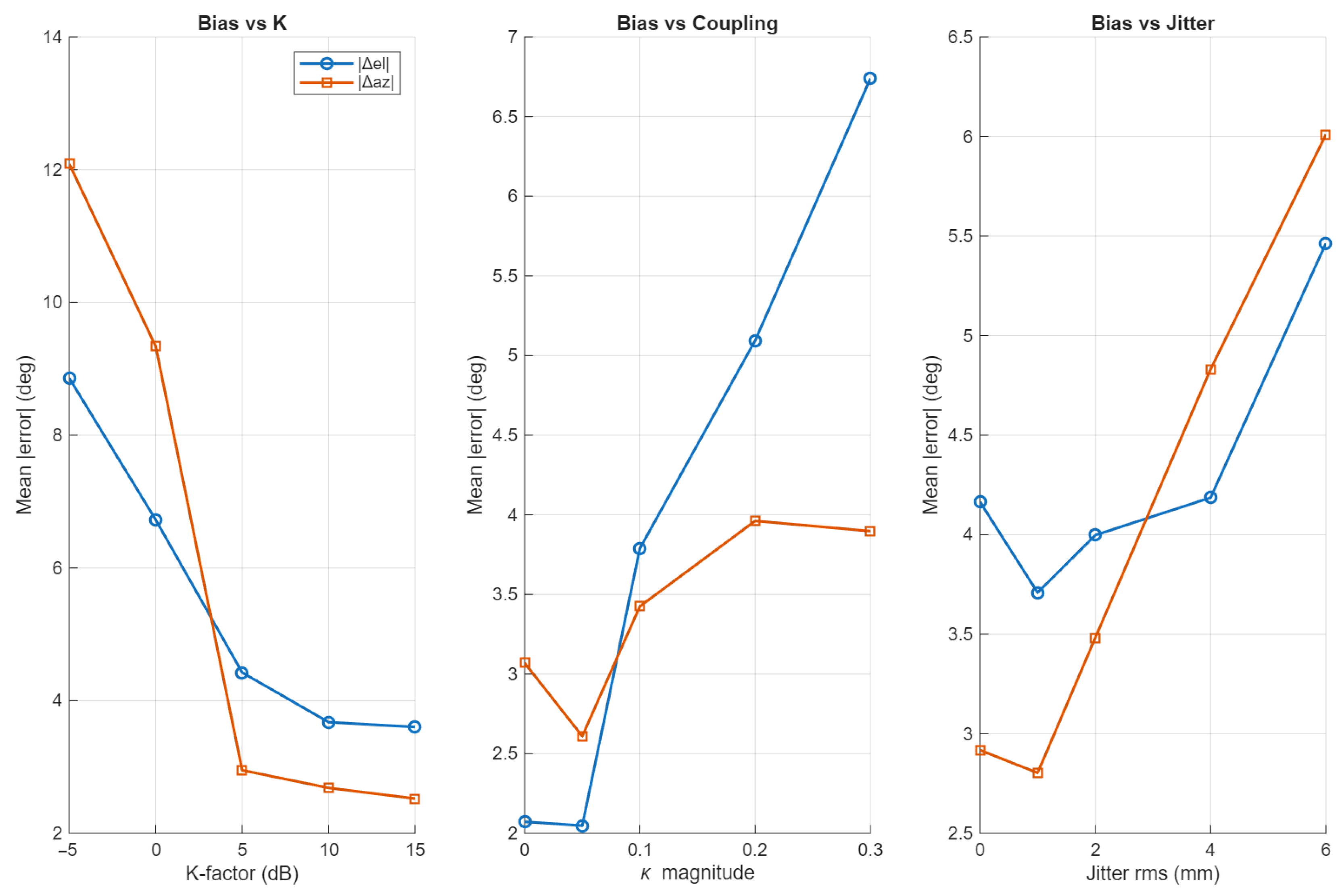

Figure 14 shows that mean absolute errors decrease strongly with

K: when scattered energy dominates (low

K), coherent multipath distorts the effective manifold and enlarges bias. As

K increases (clearer LOS), the MUSIC peak recenters and errors fall to ≈3–

. Qualitatively, lower

K values are representative of more cluttered/urban-like conditions, whereas higher

K values correspond to more open, LOS-favorable links (e.g., suburban or rural), consistent with typical Rician

K-factor ranges reported in measurement studies. Bias grows with coupling magnitude

extracted from FEKO

S-parameters: elevation error rises from ≈

to ≈5–

as

moves into the 0.2–0.3 range, reflecting manifold reshaping by mutual coupling. Subspace robustness under increasing coupling was assessed by sweeping the coupling magnitude

, recomputing

and the noise subspace for each value, and plotting the resulting DoA bias and two-source resolution probability (

Figure 14). Within this range, the PA-MUSIC subspace remains usable, with a gradual increase in bias and loss of resolution rather than a catastrophic breakdown. Jitter studies show a monotonic increase in azimuth bias (from ≈

toward ≈

over 0–6 mm), consistent with direction-dependent phase errors from placement tolerances. These trends quantify how far a free-space dictionary deviates from the FEKO-informed manifold under realistic platform conditions.

Figure 15 reports the probability of resolving two equal-power sources separated by

in azimuth. Resolution remains low across the sweeps (highest at modest

K and small

/jitter), and degrades to near-zero as coupling and jitter increase. With the present aperture and element count, platform-induced mismatch remains at

near the practical separation limit unless a platform-aware dictionary is used.

The study demonstrates that ignoring platform effects leads to systematic bias and loss of resolution even at moderate SNR. Before field deployment, a platform-aware manifold should be assembled directly from FEKO (or OTA measurements), incorporating embedded patterns and pose dependence. This dictionary should be pose-rotated at run time and used within the Hybrid PA-MUSIC search. In the present work, the platform-aware manifold is obtained from FEKO simulations of the UAV-mounted array. The curves provide actionable targets: operate in higher-K conditions when possible and design and calibrate to keep small, and control mechanical tolerances (jitter) to a few millimeters. If close-source resolution is critical, increase aperture/element count and/or apply coherent-multipath mitigation (e.g., forward-backward averaging or spatial smoothing) together with the platform-aware manifold.

7. Discussion

This work examined Direction-of-Arrival (DoA) estimation on a small UAV for ISAC using a compact six-element UCA and a Pose-Aware MUSIC (PA–MUSIC) algorithm. Embedded-element patterns of the installed array provided a realistic basis for received fields, while channel and hardware effects (Rician LOS/NLOS mixing, mutual coupling, per-element gain/phase imbalance, and element–position jitter) were added in post-processing to emulate flight. The proposed estimator rotates candidate look vectors by the instantaneous yaw–pitch–roll and compensates platform-induced Doppler across the snapshot window, then employs a hybrid coarse-to-fine search with local refinement to locate pseudospectrum maxima efficiently.

The results show three salient points. First, pose and Doppler compensation materially stabilize the pseudospectrum in motion, preserving narrow peaks and preventing drift that would otherwise inflate errors. Second, the dominant residual errors arise from manifold mismatch, primarily coupling and mechanical jitter, because the search still uses an ideal steering model. This appears as several-degree bias floors and lowered separability for closely spaced sources, consistent with the manifold–mismatch heatmaps and the bias/resolution trends versus K, , and jitter. Third, the hybrid solver meets real-time constraints on modest hardware (fixed evaluation budget and short runtimes), making the method practical for onboard use in GNSS-denied conditions where only inertial pose and platform velocity are available.

8. Conclusions

This work presented a pose- and Doppler-aware formulation of MUSIC for UAV-mounted arrays that explicitly incorporates instantaneous attitude and velocity into the steering vector used in the pseudospectrum. The study integrated antenna design, platform modeling, and signal processing into a single evaluation framework: a six-element UCA at 2.4 GHz with radius

was designed for compact multirotor platforms and analyzed using full-wave simulations to quantify platform loading. A two-stage search policy was proposed, combining a coarse grid pass (CTF) with local weighted-annealed refinement (Hybrid), thereby removing gridding bias while retaining efficiency. Across 0–25 dB SNR, the proposed estimator achieved sub-degree RMSE (<

in both azimuth and elevation) with ideal manifolds (

Section 5), and when platform loading was introduced but the search manifold was kept ideal to expose mismatch, the mean absolute errors were approximately 5–

(

Table 11), consistent with the platform-induced gain and sidelobe changes summarized in

Table 6.

8.1. Limitations

This study evaluates a pose- and Doppler-aware MUSIC framework together with a compact UCA design using full-wave electromagnetic simulation in Altair FEKO and algorithmic validation in MATLAB. The results therefore reflect high-fidelity simulations rather than field measurements. This choice isolates platform-coupling mechanisms and search-policy behaviour without confounding factors such as regulatory constraints, safety restrictions, or uncontrolled interference. The analysis focuses on a six-element UCA optimized for small multirotors and uses an ideal search manifold to intentionally expose the effect of platform loading. Larger or sparse arrays, alternative element types, embedded real-time execution, and long-term drift effects are outside the current scope. These boundaries are consistent with the objective of establishing a controlled baseline before undertaking hardware integration and flight testing.

8.2. Future Work

Future efforts will extend the present baseline to practical testing in a dedicated follow-on study. The next step is hardware-in-the-loop evaluation and flight trials that combine the proposed estimator with live IMU and GNSS data while characterizing interference, cable effects, and temperature drift in representative missions. Further work will also explore platform-calibrated or learned manifolds to close the mismatch observed with ideal search, scale to larger or sparse arrays, and investigate MIMO ISAC configurations that enable finer angular resolution and waveform or resource co-design for ISAC link optimization under power, spectral, and latency constraints. Additional directions include lightweight online calibration for gain and phase imbalance and adaptive pose stacking for real-time operation on edge computing. These activities are planned as a separate paper that focuses on experimental methods and results, building directly on the simulation-backed foundations reported here.